#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)

Text

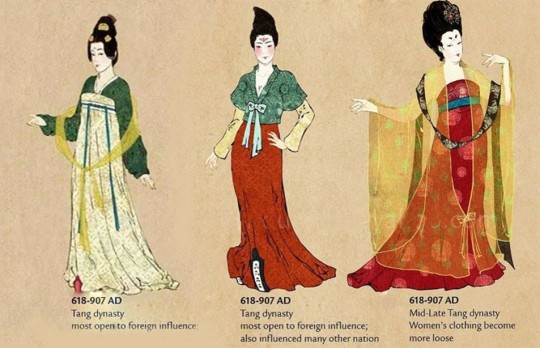

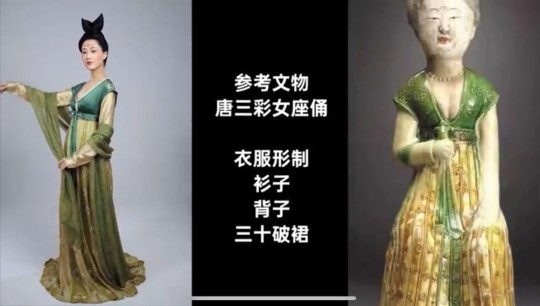

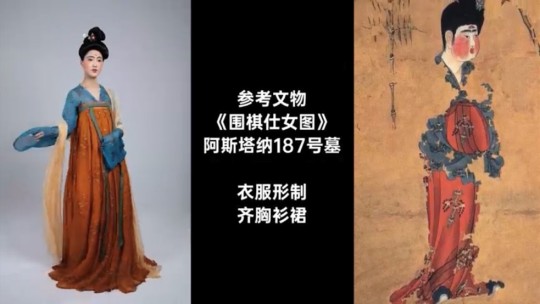

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Female figurines of Tang Dynasty

【Historical Artifacts Reference 】:

▶China Tang Dynasty Standing Female Figure,Collection of the Guimet Museum

▶China Tang Dynasty Painted double-bun female figurine,Collection of Xi'an Museum,China

————————

📸Photo:@佳期阁

🧚🏻Model :Owner of 佳期阁

👗Hanfu: @佳期阁

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/6614078088/ObZKG5Cu8

————————

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#china#chinese traditional clothing#chinese#漢服#汉服#中華風#chinese historical fashion#chinese history#chinese fashion#佳期阁

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seadall, localization, food, EABS culture, and discussion of Eating Disorder. Trigger Warning.

tl;dr: Seadall is pandering to an East Asian Beauty Standard, technically does not have eating disorder, but is bordering on Disordered Eating, and both the writers and localizers know it.

Our first official male dancer of FE has a bit of a obsession over controlling his diet to a concerning degree. But is it actually an Eating Disorder? No, I don't think so. From my pov, this has everything to do with his job, a Dancer and the dreaded East Asian Beauty Standard (EABS).

EABS idealizes the fair skinned (asian colorism rAAAAGH), the lean and thin. Any level of fats or flaps are no good and is considered undesirable, or worse, a sign of one's gluttonous and even slothful character. IRL, that sentiment has become less pervasive, less judgemental and less awful than 10 years ago, but it's still around. Hell, it's in our Fire Emblems! Average out the body shapes of all dancers or even characters in FE and you'll see what I mean.

(are you in hell yet.)

This EABS is especially prevalent in 1 genre of media that comes pouring out of Japan and Korea... The Pop Idol scene. In Japan, the idol industry can be traced back to the 1960s, and though it has propped up the EABS, this standard's roots goes FURTHER back to even pre-colonialism era, to China and the Tang Dynasty where willowy female bodies were ideal. (That's 618-907AD.)

And when I say EABS, I will include the surrounding countries outside of Japan too. Similarities in culture and all that. Hence East Asian. (Don't be mistaken though. South East and South Asia also has to deal with this shit.)

But hey. I'm still talking about female EABS, right? Where does Seadall fall into this?

Uhhhh. Jumpscare. Surprise K-pop.

(ps i dont know k-pop as well so idk who these ppl are im sorry waaaaug)

Dancers and the Idol Industry

It's easier to see on the female side, but uh, that specific body shape is often achieved through extreme dieting. The body fat % is so low that the dancer's lower ribcage can be seen. Before shooting the dance or a performance, these idol's agencies will notify them to slim down to a certain goal, like say drop 2kg (4.4 lbs) or 4kg (8.8 lbs) in x time, and this is typical. Guys here are no exception.

Weight is manufactured. Looks to some extent (plastic... surgery....). The clothes too, are intentionally picked. Exposing the belly is common since it's the quickest indicator of skinniness.

But hey, I actually lied about the dieting part. It's not really dieting as it's actually straight up starvation, tbh. To lose that weight, the dancers/idols will often eat as little as some protein shake, a few fruits and maybe potato for fiber. Yes, it's as hellish as it sounds, and no, these people are unable to fully function with a calorie intake like this. Source for this claim will be in a video at the bottom of the post by youtuber chaebin n out, titled "How K-POP Destroys Your Body". So.

W̵͓͍̏͝e̴͉̾ḽ̷͈͐ĉ̶̠̝͋ö̶̤́m̷̲̒ê̶̬ ̶̧̅ṭ̷̘͑͑ö̵͇́ ̸̛͖̑h̵̳̿͝ė̶͕͉l̵̜͖̇͗ḻ̶̑!̴̪͊̉

Ok, but that's K-pop. What about J-pop?

Japan, where FE rolls out from, have J-pop, which is slightly different. J-pop idols also suffer from EABS but afaik it's not as extreme. Many contemporary J-pop idol groups like Atarashii Gakko!(left) and Babymetal(right) also Do Not make thinness a major selling point with their costuming. This is usually done through hiding the midriff, where belly fat most easily forms. (EABS is still in effect though, don't be mistaken! There could be just as extreme cases out there I'm not aware of ;_;)

So it seems like people kind of agree that obsessing about weight and developing body image issue is messed up.

Hopefully now I've established what is going on irl for Seadall's influences, and what is considered normal or extreme. Relatively anyway. (I hate EABS so much hhggr)

Let's detour to...

Food! Staples! What's normal?

An average meal in Japan consists of a variety of veggies, tofu and a serving of protein, which results in lower fat intake. Also, RICE is a major staple in these meals, so assuming the writers are approaching it with the best intentions, and how Engage's normal might appear to native Japanese audiences, JP Seadall's worry only seems to be on oily food intake and is not overly concerning to me.

In fact, here is an example of a staple set meal (teishoku) I ate over there last December. Yum yum:

Overall a very lean meal. So it's likely Seadall eats something similar-ish and not just greens.

Another important point is that in (East) Asia/Japan, oily food is seen as unhealthy and contributes greatly to cholesterol. This aversion to oily food is driven somewhat by EABS and... Health. I also promise most people are actually chill about this. ...Most people! Meat is yummy! Gyukaku and Ikinari Steak is popular and popping! That's why Seadall likes it after all.

So this is where Seadall's writing starts to contrast. For the most part in the EN version, he only worries about meat. In JP, it's technically oily food, which meat falls under, and he's worried about putting on weight.

Why the extreme worry tho...?

The logic for why all these matters so much to him is this: if a dancer is surrounded by other dancers who are reinforcing this EABS (mirroring the standards of the real world), then their only choice to stay relevant and keep their job is to commit to the same dietary choice and uphold the same EABS, or even have a EABS outperforming the standard.

Because a Dancer's job, or rather, Seadall's job is to pander to people's ideals of beauty. Hence his supports where hair and skin and food becomes a topic.

If he fails the standard, according to the J-pop and K-pop industry, he kind of fails at his job. Is it fair? Fuck no, but no matter what opinion we may think of the standard as outsiders, it remains that there is a LOT of social conditioning and manufacturing going on leading to... all of that. I scream too. I scream a lot, internally.

So what does Seadall look like to someone in this East Asian sphere...?

To the writers credit, they do push for Seadall to indulge more food that makes him happy for at least his mental well-being through the other characters.

This also happens to fall in line with Engage's low key theme of cherishing the moment.

With all I've explained, Seadall might come across as warning to those who over-worry about oily food consumption and trying to pander to an EABS to... chill the fuck out. That it's ok to just go eat some delicious yakiniku if you want to! Go off! If a female character who is concerned with this comes across as too vain, then let's have a guy do it and hope the point lands for the (potentially female) players.

And with all these missing context, it's very easy for one who isn't clued into this sphere assume that Seadall has some eating disorder or that the writers are advocating it. I don't think that's happening here at all. The localizers likely are aware of this missing context and have toned it down several levels for EN release. Wise move, tbh.

(progressiveness can be relative btw. something to keep in mind @_@)

So, is Seadall coming close to some kind of Disordered Eating? Possible. From what I see I think the writers are trying to push Seadall away from it, and trying to stop it from becoming a full blown Eating Disorder. Personally, again, I don't think he has an Eating Disorder.

However! Your Mileage May Vary. I only hope for my opinion and understanding to help inform others, not override it. What's normal for me isn't for everyone, and vice versa, but it's important to remember where Fire Emblem originates from.

And here's the last thing I promised: the video essay if you really want to dive into it:

youtube

And that's about it.

Hope this was interesting! Thanks for reading. 😄

EDIT: the Chinese net sphere is the exception to all of this, EABS is especially bad there

#seadall fire emblem#fire emblem engage#seadall#localization discourse#eating disorder#culture#seadall fire emblem engage#trigger warning

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw the question on MDZS’s era and decided to present the result of my researches and calculations on the subject. According to tvtropes, in the Analysis page, it should take place before Tang dynasty (618-907AD). Gusu is today a district created in 2012, but Gusu was once the ancient name of Suzhou before being officialised as the latter in 589AD. The term “cut-sleeve” had been created around 4BC-1AD (from the year Emperor Ai of Han met Dong Xian to the year of former’s death). (1/4)

for the anon-y who asked!! let’s all thank new anon for taking the time for us!! hehe <3

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mulan (2020): A Scathing Review

Or, an extremely long rant by two extremely mad Chinese girls.

Before we (@hotaruyy and @meow3sensei) watched Mulan (2020), we didn’t expect too much, since the director and screenwriters aren’t Chinese (even though they claimed to want to be more culturally accurate). But holy shit, this film didn’t even fulfill our exceedingly low expectations (and we’re speaking as people who didn’t mind the loss of the musical aspect because look at the Beauty and the Beast live action). Our review will focus on our critiques of the presentation of different aspects of Chinese culture in Mulan (2020).

The Chinese Aspect of the film was especially infuriating to us as a Chinese audience. Disney emphasises that many of the changes made to the film in comparison to the animated film were to accommodate backlash regarding cultural and historical inaccuracies from Chinese audiences, but what we saw on the screen showed otherwise.

On Set Design (By a slightly irritated Architecture student)

Mix and match of architecture from multiple dynasties, which removes a lot of the sense of realism and authenticity from the film

Tang-style architecture is used (and if we’re being specific, Tang with hints of Song Dynasty) in the Imperial City’s set, which one would assume depicts the time period in which the movie is set in. Identified by the wooden balustrades, relatively simple and small dougong, vertical lattice windows, wooden piles for waterfront, organic shapes in landscape architecture etc. (fig. 1)

fig. 1 - Scene in film

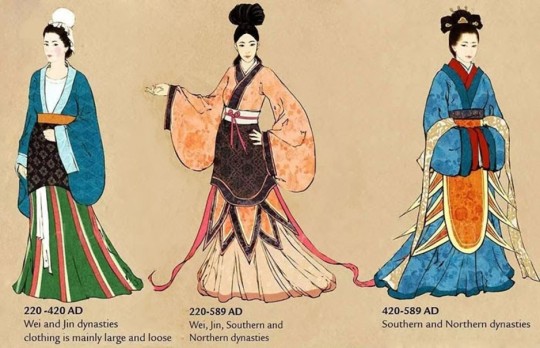

Understandably, information on architecture before Tang (618-907AD) is scarce, so I do think there was an attempt at referencing the original poem that was written during the Southern and Northern Northern Wei Dynasty 南北朝北魏 (386-581AD). Taking creative liberty here makes sense.

That being said, the film didn’t care for retaining a consistent style of architecture, resulting in a wormhole of a set that somehow spans five different dynasties. Only two examples will be listed to avoid an entire essay :)

Exhibit A. Mulan’s home in Hakka Tulou 客家圍土樓 (fig. 2) (roughly translates to Hakka Mud Towers), which originated in the Song and Yuan dynasties (960-1368AD), and started maturing in the late Ming dynasty. (Why use something that didn’t even exist when the Ballad was written and by doing so, physically place Mulan in Fujian?? Just put her in an ambiguous village like how the animation did??). Somehow Tulou started existing before the Hakka clan migrated down south :) To put it simply the presence of Tulou is a locational and historical bug. The jump from the Hakka Tulou to the Tang-styled Imperial palace (fig. 3, which is strictly speaking a hybrid of different styles but I’d argue still mostly Tang) in the opening scenes is only a taste of the amount of inconsistencies later seen in the film.

fig. 2 Scene in film - Hakka Tulou

fig. 3 Scene in film - the Imperial Palace

Exhibit B. This scene (1:20:14) showing Qing Dynasty architecture in what is supposed to be a Tang Dynasty setting, identified by more elaborately decorated dougong 斗栱 (fig. 4 a key feature in the structural system in Chinese architecture, referring to the interlocking structure that sits on top of each column; at least three different kinds of dougong from three different dynasties have been spotted in the film).

fig. 4 Examples of different Dougong in Ancient Chinese architecture (top left being a good example of Tang-styled Dougong)

An insignificant building is not supposed to have more glamorous and larger dougong than the Imperial Palace, not to mention the lack of decorative dougong at all during the Tang Dynasty.

fig. 5 Scene in film that features a building with dougong

fig. 6 Shenyang Imperial Palace built in the Qing Dynasty

An actual Qing Dynasty Palace (fig. 6), for reference, and a random scene from the film (fig. 5). Note the larger dougong both fig. 5 and 6 (the ratio of dougong to column is significantly larger) with more layers of interlocking segments, as compared to the Tang-styled dougong that we pointed out earlier.

On Costume Design

Blue fabric on people who are NOT ROYALTY/NOBILITY. Soldiers guarding the imperial gate would not be wearing blue shirts under their armour. There wouldn’t be such a big supply of blue fabric in the first place; blue fabric would absolutely not be mass-produced for soldiers.

Ancient Chinese people made blue dye from crushed butterflies, did no one care enough to consider the sheer amount of wealth it takes to dye blue fabric organically? Soldiers would very simply not be wearing blue fabric because of how expensive these colours were at the time. Artistic liberty is fine but at least make it make sense in a clearly hierarchical society??

The painful inaccuracies in Mulan’s costume in the matchmaking scene (fig. 7). Ah, the scene that managed to translate breathtaking Hanfu (and there are plenty of resources to take inspiration from) into a Western caricature of a Chinese Halloween costume.

fig. 7 Scene in film featuring Mulan’s Hanfu from the matchmaking sequence

There’s nothing wrong with taking artistic liberties for costumes with a historical context. For instance, exaggerating certain characteristics of the era the story is in, or modernizing certain features so that they align with the character’s more modern way of thinking to contrast with the traditional setting. Good examples that come to mind are the costume designs in Marie Antoinette (2006), or Nirvana in Fire (2015), which also happens to be a Chinese period piece set in a fictional, historically ambiguous era. Inspiration for its costume design is taken from the Han Dynasty and the Southern and Northern Dynasties, so its costumes combine clothing silhouettes from the two periods, and use different characteristics such as colour to reflect class and status, and to represent characters’ personalities. It does a really good job of creating a new style while still giving subtle visual cues to the audience.

But Mulan’s dress can hardly be called an interpretation of traditional Chinese clothing. This is something the animated film did poorly on as well, and this probably contributed to the costume design in this film as an adaptation of the cartoon. The fabric had a shiny sheen that cheapened the costume. Coupled with the strange silhouette of the Hanfu (especially the bottom part of the skirt), this further detaches the audience from any hint of authenticity. The pictures below can speak for themselves. If they’re aiming for ambiguity in terms of the dynasties as seen in the set, then at least make something that is visually pleasing??

fig. 8 Evolution of Hanfu

fig. 9 Tang Hanfu recreated with references from Tang artifacts (top: early Tang; bottom: golden era of the Tang period)

For whatever reason it seems like the extras in the background have more accurate costumes than the main character

And as a girl from a farming village why is she being trained like a noble lady??? A question I’ve had since the animated film…

The film wasn’t consistent when taking artistic liberties. Audiences subconsciously make visual connections to historical periods when watching a historical fiction film. It would be visually more cohesive if artistic liberties were taken on elements from one dynasty or by combining elements from dynasties with similar aesthetics, instead of jumping across centuries of very different stylistic approaches.

Basing the set design on the Tang Dynasty, but then including random shots of Qing Dynasty architecture of no particular importance (two very contrasting architectural styles); extras having Tang-style Hanfu, but Mulan not having one that's remotely close to any style of the multiple dynasties the film has taken inspiration from; alluding to the time period in which the ballad was written by painting Mulan’s forehead yellow 黃額妝 (which was poorly done but I digress), a style of makeup used by women of the Six dynasties and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (六朝女子), but everything else alludes to Tang or later. And finally, basing many things off the Tang Dynasty, but the Tang wasn’t in risk of invasion from the Huns or the Rouran??? We’re fucking confused :)

Small details like the ones we’ve listed above are visually off-putting; as an audience member I’m immediately thrown out of whatever universe the film is building due to the contradicting visual cues. If this was Disney’s and the director’s attempt at cultural accuracy, then it’s plainly insulting to the intelligence of their Chinese audience. (Respecting cultural concerns should not be Disney’s scapegoat for producing a bad movie.)

Ultimately, the film is based on a ballad and we wouldn’t say the points we’ve mentioned are considered common knowledge. So let’s treat it as a fictional era and put less significance on historical consistencies and authenticity. Let’s narrow it down to the crude representations (and misrepresentations) of general Chinese culture and society.

On Stereotypes

“Chi”: Why are soldiers receiving chi-related martial arts training, which takes years and years of elite, specialised training and experience? Ordinary soldiers don’t train their chi, they are not Wuxia 武俠 (roughly translates to martial arts chivalry). These people aren’t training for Jianghu martial art contests (江湖俠道的比武), they are training to kill for war, which does not require finesse at all. Even disregarding the lack of logic in training ordinary soldiers in martial arts (especially them teaching Taichi in the film), logistically it is simply not worth the economic and time cost of training entire regiments in martial arts only for them to be mostly killed off in battle. (Sorry, it’s difficult to explain wuxia and jianghu in a few words, but they’re super cool so please search them up if you’re interested!)

Many others on tumblr have commented on how chi itself is not the weird masculine "power" the film made it out to be, which is also very true (it's also actually very interesting so search it up if you want to!)

On Language as a Limitation

Clumsy translations of Chinese idioms and phrases that are just tragic comedy, e.g. 四兩撥千斤 being translated into “four ounces can move a thousand pounds”, which neglects the subtlety and gentle vibe of the original word choice while twisting the concept into something related to brute force or physics (but we guess this specific example is not entirely the screenwriters’ fault, since some English Taichi classes also translate it as that).

Replacing Chinese concepts and mythology directly with Western concepts such as witches, phoenixes rising from the ashes etc.

The single clumsy reference to the original “Ballad of Mulan” 雄兔腳撲朔,雌兔眼迷離;雙兔傍地走,安能辨我是雄雌?(translates to: when being held by the ears off the ground, male rabbits would have fidgeting front legs, while female rabbits close their eyes; who’s to tell male and female apart when the two rabbits are running side by side?) This line is an acknowledgement and compliment to Mulan’s intelligence and capabilities. It also challenges patriarchal beliefs of gender and women.

On Traditional Virtues (or the oversimplification of them, and a continuation of Language as a Limitation)

The film’s traditional values of 忠勇真 (translated as loyal, brave, and true in the film by using the most direct translations possible) and 孝 (translated as "devotion to family" in the film) seem to be a reference to the core values of Confucianism. We assume that the film is referencing these Confucian core values: 仁 (to be humane)、恕 (to forgive)、誠 (to be honest and sincere)、孝 (filial piety) and 尊王道 (to be loyal to the emperor). If the screenwriters were going to use traditional values, it is curious for them to choose only those three specifically, and to grossly simplify the actual values in their choice of Chinese characters (instead of using the conventional characters), then to grossly simplify them again in their English translations, and then to put them together in that order. The film also just briefly goes over the values by plainly listing them out in the form of an oath, thereby erasing the complexities of the values...

In a hilarious weibo post by 十四皮一下特别开心, they point out that the three values of 忠勇真 used in the film actually directly translate and correspond to the FBI motto of “Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity” :)

Let’s talk about 孝, the fourth traditional virtue engraved in the sword gifted to Mulan by the emperor at the end of the film. Over everything else, this is the original ballad’s central moral, and what we believe the film is also trying to evoke, so the weak translation diminishes the story’s message. The animation was smart in not directly translating it and instead demonstrates what it entails through the progression of the plot. The film does the opposite and translates it as “devotion to family”, when they could have just referred to it as filial piety. Care, respect, thankfulness and giving back to one’s parents and elderly family members. While obedience and devotion are part of what the virtue teaches, it's not supposed to sound like an obligation, it’s not something ritualistic, it’s just something everyone does as a “good” human being.

(And if the director and screenwriters were trying to diminish the role and significance of filial piety in the film on purpose because they wanted Mulan to appear “stronger” and “individualistic”, then… I really have no words for how painfully insensitive that is in terms of how white feminism does not and should not apply to or be imposed on other cultures.)

And here’s our list of Things That Also Pissed Us Off that other people on tumblr have talked about already, which is why we’re mentioning them without much elaboration:

On Feminism

We get that Disney was trying to make a female empowerment movie but they really missed the mark? Even with a female director, somehow. Stepping back and ignoring the Chinese aspects of the film, as a female audience this film was equally, if not more, hurtful

Mulan is only seen as “strong” because of her extraordinarily powerful “gift” of chi that led to her being physically more powerful than the men, especially in that scene where she lugs the two buckets of water to the peak of the mountain (which is in sharp contrast to how Mulan in the animated film is strong because she’s intelligent and is able to utilise teamwork and her strengths properly, and doesn’t let her understandable disadvantage in terms of physical strength trip her up)

All female characters are one-dimensional as fuck and are mere caricatures (though to be fair, the male characters aren’t treated much better) BUT PEOPLE, MULAN IS THE MAIN CHARACTER!! Her name is literally the name of the film!!! Maybe give her some character??? And what happened to wanting to produce good Asian representation in Hollywood???

The character of the witch was slightly more complex than everyone else, which, good for her, but then the screenwriters had her killed when she could easily have not been written with that conclusion to her arc?? Seems to us like some bullshit where the witch had to be punished in a narrative sense because she “succumbed” to using her powers (which are again dubiously chi-related) for “evil”, when instead she was merely trying to achieve as much as she could for herself in a patriarchal system designed to punish her

Plus the implication of writing the sequence of the witch sacrificing herself for Mulan is that Mulan is inherently more worthy of protection because she’s more “noble”, which, again, we call bullshit. Mulan achieved (impossible) success and validation in a patriarchal system because she played by their rules of what it means to be a masculine “warrior” and excelled, while the witch is scorned and punished within the story and also in a narrative sense because she doesn’t. Is that really what it means to be noble and good???? Does that really make Mulan superior to the witch?? (Honestly this plot point might have worked if there was more complexity written into the script, but unfortunately there wasn't)

Can’t believe they just threw away what could have been a perfectly complex and compelling relationship between Mulan and the witch because of shitty writing

The way Mulan lets her hair down and dumps her armour as an indication of her female identity (which is irritating to us on so many levels, as explained by various tumblr users)

On Production

Plot and character arcs have no emotional tension; they’re super rushed and super shallow; emotional beats are not hit properly (e.g. Mulan’s loyalty and friendship towards the soldiers, built up with one line from Honghui “you can turn your back on me...but please don’t turn your back on them” kind of bullshit)

The screenwriters would not know character depth or development even if it were shoved in their face

Blatant symbolism and metaphors (e.g. the fucking phoenix, and thank fuck it doesn’t look like a western phoenix) that make the film feel very… low.

Cinematography and editing: some very beautiful and compositionally interesting shots, but the battle scenes lack tension. The jump cuts disrupt the rhythm and intensity of the fighting; in combination with the overuse of slow motion, they drag the pace of the choreography and further slow down the rhythm of the scene. Exaggerated colour toning make certain scenes more fantastical than others, resulting in a mix of realistic landscapes in some scenes and highly saturated unnatural colours in others, which draws the audience in and out of the film’s universe. This is a shame because they actually took the effort to film in real landscapes.

fig. 10 Scene in film

Special effects: lack of blood in battle scenes (which, fine, they want it to be family-friendly) and Mulan’s suddenly clean face after she returns to her female identity visually puts off the audience (and links back to the issues surrounding the visual representation of her femininity)

And here’s the extremely short list of Things That We Liked:

That first fight scene between the witch and mulan when the witch brushes mulan’s hair away from her face with her claw while restraining her because that was gay as fuck and I am but a weak bisexual!!!

Donnie Yen’s action sequences lmao (they’re not even among the better ones he’s done so everyone go watch Ip Man for actually good action sequences and choreography)

Just listening to the soundtrack itself was great, loved the Reflection variations but I was simply too distracted by the other shitty things in the film

All-asian cast (thank fuck) with impressive actors and actresses (who should not be blamed for a shitty script)

TL;DR: This film is not worth your time or money. Inferior to the animated film (which already has a few questionable aspects). If you’re somehow really interested in seeing how badly Disney butchered Chinese culture (and to a certain extent the animated film), then just pirate this film. If you want to know what happened but can’t be bothered to waste your time watching the film, read this amazing and hilarious twitter thread by @XiranJayZhao, which we found right before we posted this review, and pretty much sums up our viewing experience as well.

Disclaimer: At the end of the day we're two girls from a predominantly Chinese society who are used to Chinese period films and dramas, watching Mulan (2020), a film primarily meant for Chinese diaspora and audiences in the West, with the Chinese market in Asia being just a secondary economic opportunity for Disney. We do realise that we aren't this film's target audience, and that we're not at all experts in everything we've discussed in this review. A lot of this is just us nitpicking, and all of it is just our personal (and very emotive) opinions from watching this film. Mostly we're just disappointed that the film was advertised to be relatively realistic and culturally accurate, but… wasn't.

Sigh.

Btw please feel free to ask us for recs of actually good, actually Chinese films and shows lmao.

Finally, all the love to our beta @keekry, for her many suggestions and hilarious comments!!!

#mulan#mulan 2020#mulan 1998#mulan live action#chinese culture#chinese architecture#chinese clothes#chinese costumes#chinese fashion#hanfu#mulan spoilers#long post#film review#disney#as a side note i have no idea why everyone thinks it's pronounced xian lang when in fact it's xian niang

15 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Yao Yimin 5 hours ago

I feel like I really have to type this comment though it’s a very unpopular opinion that most audience wouldn’t know or care about. As a Chinese living in Asia who knows and loves Chinese history, I’m really Glad that Disney is making a production that is based on the original poem of Mulan. But it is slightly disappointing to see that despite going for realism, Disney isn’t paying enough attention to really hit the settings of the story right.

Not even going into how weird it is that they are all speaking in English,

The earliest documentations of the story of Mulan were from the Wei Dynasty(about 380-540AD) in Northern China, so it is reasonable to assume if she was a real character, that’s when and where she was born. But the architecture shown here (Tulou) only appeared during the Song Dynasty (960AD) and really gained popularity in the Ming-Qing dynasties(1368-1912AD) in Sourthern China. So the settings is about 1000years off half a China away.

Furthermore, the makeup that Mulan was wearing was distinctly Tang-makeup, which was extremely popular during the Tang dynasty(duh) 618-907AD. Sooo that’s another time period completely off.

While I do get that Disney is trying to promote Chinese culture, since Tulou are UNESCO heritage sites and Tang was the most prosperous Dynasty in Chinese history, and that only a small minority of the audience will even notice these details, if still bugs me because it’s like making a movie about the birth of Jesus but he was born in UK at the same time as Issac Newton.

At least at this point in time, I much prefer the animated version over this since that one is made in a light mood with a modified story instead of a not-so-good attempt at keeping it historically realistic

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Li ZiQi, Who is she?

LI ZIQI – A Modern Chinese Fairy

She is born in the 90s. She’s a girl who lived in the deep mountains of Sichuan (Szechwan), China. Unlike other online celebrities, although she’s famous on the Internet nowadays and always appears in beautiful clothes, Li ziqi was always wearing a modified version of Hanfu (a kind of Han Chinese traditional clothing) back then. She was using the most traditional method, the most traditional tools, but a unique perspective to present Chinese traditional dishes.

She is a “Wonder Woman” in the eyes of her fans, as she can achieve what normal people cannot. Once again, she has shown people the styles of the Han(202BC-220AD) and Tang Dynasty(618-907AD) and let them know more about what life in the countryside is like. She also enables people to experience the life in the countryside which contemporary Chinese people strive for.

For the people living in the cities, this would be like discovering the unknown and exploring an ideal way of life on the farm. People admire her, especially because she uses her own way to combine the elements of the ancient Chinese and the modern life, showing to her audience the traditional Chinese pastoral life and the process of Chinese food production. Her videos fully explain the Chinese people’s traditional concept of family, the Taoist thought of harmony between man and nature.

Who is Li ziqi?

Li Ziqi (Chinese: 李子柒)was born in the remote mountain village of northwestern Pingwu, Mianyang city, China. (Sorry, we can’t release much more personal information of her for protecting this beautiful girl.) She did not have a happy childhood like most of the children. When she was little, her parents got divorced and his father died early. Then, she started living with her grandparents. Their life was poor, but it was also relatively stable. Li Ziqi’s grandfather was a cook working in the countryside. When there was a ceremony going on, be it a wedding or a funeral, her grandfather would be in charge. In the videos, she showed how to cook various dishes, which she had learned from her grandfather. Besides cooking, she also learned how to make bamboo baskets, fishing, growing vegetables and doing carpenter work from her grandparents.

Li ziqi ’s stories of growth

At the age of 14, when most of the kids of the same age went to middle school, Li Ziqi dropped out of school and tried to support herself by doing various jobs. She has not been treated well, nor was her fate particularly good at the initial stage of her life. She struggled much to survive – she starved, slept in a cave under a bridge, worked as a waitress, an electrician, sold Hanfu, and she even worked as a DJ at a nightclub. However, after working for 7 to 8 years, it became clearer to her what she really wanted. It also helped her develop the ability to think and judge independently. Also, with all these experiences, she has developed a sense of ‘danger’. No matter what happens, she must keep enough deposits in her bank account in case there is an emergency.

In 2012, her grandmother had a serious illness. Li Ziqi decided to give up everything and return to her hometown so that she could take care of her grandmother. The life at hometown was relaxing. She started work early in the morning and returned home late. Like other farmers who earned their living on the farm, she was living an ordinary life in the countryside.

1 note

·

View note

Text

What do Rich Men and Gold Turtles Have in Common?

In Chinese, a rich son-in-law, or a rich husband, is often referred to as a “Gold Turtle Husband”, or 金龟婿 (jīnguīxù)” . Are you looking for your golden turtle? Does this phrase make any sense to you? Probably not. There is, however, an interesting story as to how this phrase began. Let’s learn more:

During ancient China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907AD) an official whose titles were equal to, or above, three ranks would adorn themselves with a fish emblem. Officials with five or more rankings would receive a turtle emblem instead of a fish. Princes, or those officials with a very high ranking, would wear golden tallies of their rankings and ordinary officials would wear copper tallies for theirs. Hence, a gold turtle would be the highest-ranking, and most likely wealthiest, men available. Women who are considering a husband might dream of one day finding their man with the golden turtle to marry and living a life of luxury. Therefore, they would be looking for her “金龟婿 (jīnguīxù)” Gold Turtle Husband”.

Although we don’t necessarily limit “金龟婿 (jīnguīxù)” Gold Turtle Husband” to princes and high-ranking officials, today we carry on this tradition of referring to a...

...for the FULL LESSON on “金龟婿 (jīnguīxù)” Gold Turtle Husband”, YOU CAN READ ALONG WITH US HERE!

#金龟婿 (jīnguīxù)#mandarin chinese word#chinese language learning#learn chinese online#chinese rich husband#chinese golden turtle

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ)

Eben van Tonder

10 May 2020

Introduction

Xuanwei Han in Xuanwei City. Reference China on the Way.

Yunnan is one of China’s premium food regions known for exquisite tastes. One of the major cities in this picturesque region is Xuanwei, where one of the world famous Chinese hams are produced, the others being Jinhua Ham from Zhejiang province and Rugao Ham from Jiangsu province. Yunnan Xuanwei Ham is known for its fragrance, appearance, and out-of-the-world taste. Through the ages, there have been many references in literature to the health benefits associated with the hams. In order to produce these hams, there are at least two ingredients without which the hams can not be produced. The first ingredient is salt.

The Industrialisation of Ham

Early references to Xuanwei hams go back to 1766. “Old chronicles recorded the Qing emperor Yong Zheng five years (the year 1727) located XuanWei (a city of YunNan province, China), so it is called XuanWei ham. (China on the Way) In 1909, Zhuo Lin’s (Deng Xiaoping’s third wife) father Pu Zai Ting, a businessman, mass-produced it for the first time. He established Xuanhe Ham Industry Company Limited. His company sent food technicians to Shanghai, Guangzhou (formerly Canton), and Japan to learn advanced food processing technology.

One example of the excellence pursued in Guangzhou relates to the cultivation of rice. Rice breeding began in China in 1906. However, by 1919, systematic and well-targeted breeding using rigorous methodologies was started at Nanjing Higher Agricultural School and Guangzhou Agricultural Specialized School. Between 1919 and 1949, 100 different rice varieties were bred and released. (Mew, et al., 2003) For a riveting look at the trade in Guangzhou, see the work by Dr. Peter C. Perdue, Professor of History, Yale University, Canton Trade.

By all accounts, Pu Zaiting was successful in creating a world famous ham (at least by probably standardising and industrialising the process). In 1915 Xuanwei ham won a Gold Medal at Panama International Fair. The ham, which, in the Qing and Ming Dynasties, was a necessary gift for friends and guests and which, during the gourmet festival, became the main ingredient to create different delicious dishes achieved international acclaim. (chinadaily.com)

The Xuanhe Canned Ham Industry Company Limited was established on the back of canning equipment bought from the United States of America to produce canned ham. Most of what it produced were exported overseas. In 1923 Sun Yat-sen tasted the ham at the National Food Exhibition held in Guangzhou. Sun famously wrote of the ham, “yin he shi de” translating as “eat well for a sound mind!” By 1934, four companies were producing the canned ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Xuanwei Ham expanded greatly under the People’s Republic of China, established in 1949. Supporting industries started to develop. A factory was created to supply the cans used by the Municipal Authority of Kunming City. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Production of Xuanwei hams rose by 1999 to 13 000 tonnes, made by 38 large producers. In 2001 it got the status of a regional brand, protected by the People’s Republic of China. A Chinese standard, GB 18357-2003 was subsequently issued. By 2004 production rose to 20,750 tonnes with technology in manufacturing and packaging improving continuously. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Apart from a rich and competitive environment, an entrepreneur, as the proverb goes, worth his salt, was needed to bring discipline to the production process and to establish this ham among the finest on earth. In achieving this status, three elements were required, namely salt, the right meat and a solid production technique to yield this culinary masterpiece on an industrial scale.

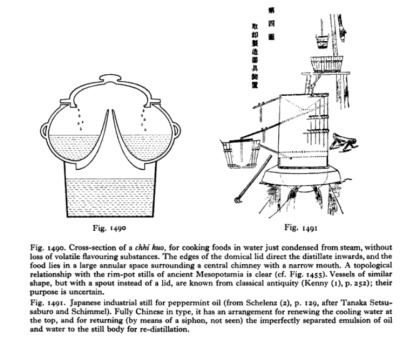

Yunnan – Centre of Culinary Excellence

The first requirement for competitiveness is an environment of excellence and innovation. The environment where this exquisite ham is produced testifies to culinary excellence. Like Prague, which produced the ham press, nitrite curing and the famous Prague hams, the Yunnan hams likewise hail from an area replete with food and cooking innovations. Yunnan is located on what was known as the Southern Silk Road and its culinary excellence is seen, among other things, in the equipment used in preparing their foods. Joseph Needham, et al. reports that in restaurants in the cities of Yunnan, a very special dish is found “in which chicken, ham, meat balls and the like have been cooked in water just condensed from steam. This is done by means of an apparatus called chhi kuo (or formerly yang li kuo) made especially at Chien-shui near Kochiu. It consists simply of a red earthenware pot with a domical cover, the bottom of the pot being pierced by a tapering chimney so formed as to leave on all sides an annular trough (figure 1490). The chhi kuo once placed on a saucepan of boiling water, steam enters from below and is condensed so as to fall upon and cook the viands of the trough, resulting thus after due process in something much better than either a soup or a stew in the ordinary sense. Since the chimney tapers to a small hole at its tip no natural volatile substances are lost from the food, hence the name of the object and the purpose of its existence. The chhi kuo must claim to be regarded as a distant descendant of the Babylonian rim-pot (for it has and needs no Hellenistic side-tube) with the ancient rim expanded to form a trough, compressing the ‘still’-body to a narrow chimney. But how the idea found its way through the ages, and from Mesopotamia to Yunnan, might admit of a wide conjecture.” (Needham, et al.,1980)

The second essential ingredient for a salt-cured ham is salt. Salt is something that China has been specialising in for thousands of years and which became the backbone of the creation of this legend.

Salt in China

Flad, et al. (2005) showed that salt production was taking place in China on an industrial scale as early as the first millennium BCE at Zhongba. “Zhongba is located in the Zhong Xian County, Chongqing Municipality, approximately 200 km down-river along the Yangzi from Chongqing City in central China. Researchers concluded that “the homogeneity of the ceramic assemblage” found at this site “suggests that salt production may already have been significant in this area throughout the second millennium B.C..” Significantly, “the Zhongba data represent the oldest confirmed example of pottery-based salt production yet found in China.” (Flad, et al.; 2005)

Salt-cured Chinese hams have been in production since the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD). First records appeared in the book Supplement to Chinese Materia Medica by Tang Dynasty doctor Chen Zangqi, who claimed ham from Jinhua was the best. Pork legs were commonly salted by soldiers in Jinhua to take on long journeys during wartime, and it was imperial scholar Zong Ze who introduced it to Song Dynasty Emperor Gaozong. Gaozong was so enamored with the ham’s intense flavour and red colour he named it huo tui, or ‘fire leg’. (SBS) An earlier record of ham than Jinhua-ham is Anfu ham from the Qin dynasty (221 to 206 BCE).

In the middle ages, Marco Polo is said to have encountered salt curing of hams in China on his presumed 13th-century trip. Impressed with the culture and customs he saw on his travels, he claims that he returned to Venice with Chinese porcelain, paper money, spices, and silks to introduce to his home country. He claims that it was from his time in Jinhua, a city in eastern Zheijiang province, where he found salt-cured ham. Whether one can accept these claims from Marco Polo is, however, a different question.

Salt Production In and Around Yunnan

When it comes to salt, only a very particular variety is called on to create this legend.

Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau

Around the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau are three salt producing areas which took advantage of the expansion of China towards the west in the early modern era. “Szechwan with a slow but steady advance; Yunnan with the speed and initiative characteristic of a developing mining area; Mongolia with a sudden, temporary eruption.” (Adshead, 1988) As fascinating as Szechwan and Mongolia are, we leave this for a future consideration and hone in on Yunnan.

Szechwan not only supplied its own requirements for salt, but also that of Kweichow, Yunnan (trade started in 1726) and western Hupei. Despite the fact that Yunnan imported salt from Szechwan and possibly from Kwangtung, this was mainly to supply its eastern regions of the escarpment. On the plateau it had salt resources of its own. By 1800, it is estimated that it produced 375 000 cwt (hundredweight).”These salines formed three groups: Pei-ching in the west near Tali the old indigenous capital; the Mo-hei-ching or Shihi-koa ching in the south near Szemao close to Laotian and Burmese borders; Hei-ching in the east near the provincial capital Kunming. (Adshead, 1988) It is this last group that captures our imagination due to the connection with the Yunnan hams.

Although known as ching or wells, many of the Yunnan salines, especially those in the Mo-hei-ching group, were in the nature of shafts or mines, though the low grade rock salt was generally turned into brine and evaporated over wood fires. The growth of the Yunnan salines in the Ch’ing period was the product of two forces. First, Chinese mining enterprise, often Chinese Muslim enterprise, which in the 18th century was turning Yunnan into China’s major source of base materials – copper, tin and zinc. Second, the extension of direct Chinese rule into the area, the so-called kai-t’u kuei-liu, initiated particularly by the Machu governor-general O-er-t’ai between 1725 and 1732. (Adshead, 1988)

The distant past of Heijin comes to us, courtesy of Yunnan Adventure Travel, who writes that “the unearthed relics of stones, potteries, and bronze wares have proved that as early as 3,200 years ago, ancestors of some minority groups already worked and multiplied on this land. It’s recorded in the “Annals of Heijin” that, a local farmer lost his cattle when grazing on the mountain, he finally found his black cattle near a well; but to his surprise, when it lipped the soil around the well, salt appeared; thus in order to memorize the black well, the place was nicknamed as “Heiniu Yanjin” which means the black cattle and the salt well. It’s shortly referred to as Heijin afterwards.” (www.yunnanadventure.com) Some accounts of the story have it that it was a Yi girl who was looking for her missing oxen when she came upon them licking salt from the black well.

Who better to take us on a tour of the old town than a seasoned traveller! We meet such a wanderer in the old city of Heijin in the person of Christy Huang. She takes us on an epic adventure, discovering the old salt kingdom of Hei-ching. She posted it on Monday, November 30th, 2015 and she called her post “Old Towns of Yunnan, Heijing.”

Christy writes that “the quite fameless Old Town of Heijing (黑井古镇) – today one of the nicest in Yunnan – used to be famous for the high-quality salt which was produced there since hundreds of years. The once most important town of Yunnan is hidden at the banks of Longchuan River in Lufeng County of Chuxiong Prefecture of Yunnan.

Salt production in bigger scale began in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and peaked during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) Dynasties. Besides the overall beautiful picture of Hejing and its surroundings, there are a couple of scenic spots worth mentioning:

Courtyard of Family Wu,

Ancient Salt Workshop,

Dalong Shrine, as well as,

Heiniu Salt Well.

The Courtyard of Family Wu used to be the residence of former salt tycoon of Heijing Old Town. The mansion was built during 21 years in mid 19th century and is formed in the shape of the Chinese character wang (王), which means king. It has 108 rooms, which have been left more or less unchanged. Today it serves as an (expensive) hotel for Heijing visitors.

The Ancient Salt Workshop was Heijing’s core place and fortune fountain. The remaining huge water wheels and stages for making salt testify the great prosperity of the bygone times. The salt produced in Heijing is as white as snow. It was and is used for preserving Yunnan’s well-known Xuanwei Ham.” (Christy Huang, 2015)

Wujin pig

The third ingredient in the production of Yunnan Xuanwei Ham is the pigs. Traditionally, the rear legs of the Wujin pig breed are used. The breed is known for its high-fat content, muscle quality and thin skin (chinadaily.com).

The breed is usually kept outdoors and is typical in the Xuanwei region. They are normally fed on corn flour, soybean, horse bean, potato, carrot, and buckwheat. They are slow growers, but their meat is of superb quality.

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei (China Daily) wrote a great article about these pigs for the Yunnan China Daily entitled “Yunnan’s little black pig by the Angry River.”

They write that “there is a quiet little revolution taking place by the banks of Nujiang River, the “angry river”, the upper stretch of the famous Mekong as it passes the narrow gorges near Lijiang. Here, little black pigs wander freely by steep meadows, grazing on wild herbs and foraging as freely as wild animals. They are relatively small, compared to their bigger cousins bred in farms. These sturdy little animals are reared for about two to three years before they are slaughtered and made into the region’s organic hams – called black hams for their deep-colored crusts.” (Yingqing and Anfei)

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei report on “Wang Yingwen, a 47-year-old farmer who has raised the black pigs for more than 30 years, says the pigs are fed spring water and they live on wild fruits, mushrooms and ants on mountains, an all-organic diet if there was one. (Yingqing and Anfei)

With increased industrialisation came the demand for a faster growing animal. Wujin pigs were being crossed with Duroc (USA), Landrace (Denmark), and York (UK) to achieve faster growth. Wujin x Duroc were crossbred. Other crossbreeds are York x (Wujin x Duroc) and DLY (Duroc x (Landrace x York). Yang and Lu (1987) found that the cross itself does not materially influence the quality of the ham as long as the breed contains 25% Wujin blood. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

In Xuanwei City, pig production is big business! In 2004, the city loaned 120 million yuan to breeders. By this date, the city had 31 breeding facilities each yielding 3000 pigs annually. There were an additional 9600 small breeding facilities. 356 Animal hospitals support the breeding and husbandry operations. In Xuanwei City, 1.2 million pigs were sold in that year. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Consumers want a great product (consistency, despite volumes offered by industrialised processes) and a great story (focussing on the ancient history of the process and ham itself). Work to accomplish this was funded by the Yunnan Scientific Department, the Yunnan Education Department and Xuanwei City Local Government who all promoted the continued development of the Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ). (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) Modern processing methods moved away from seasonal production and embraced modern processing technology, but the great legends of the past remain as well as tailor-made production techniques catering for year-round production.

Processing Yunnan Xuanwei Ham

The Xuanwei climate explains the production methods used, as is the case with all the great hams around the world. Xuanwei City is located on a low-latitude plateau mansoon climatic area where the north sub-torrid zone, the southern temperature zone, and the mid-temperature zone coexist. Winter lasts from November to January and spring occurs from February to April. February, March, April is sunny and clear and this leads to a low relative humidity during these months. From March to September it is overcast and rainy, and the relative humidity is comparatively high. Winter is the best time to salt the hams according to the old methods to limit microactivity till salt dehydrates the meat and reduces the water activity. The rainy season is best for fermenting the ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

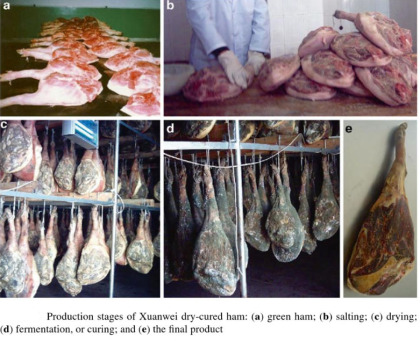

Production

As in all meat processing, making the hams start with good meat selection. The process starts in the winter. The animal is killed and all the blood pressed out by hand. Animals are between 90 and 130 kg (live weight) when slaughtered.

by Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016

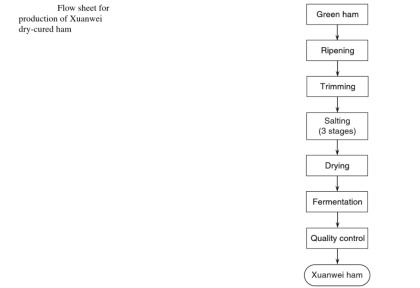

A simple flow chart is given by Kristbergsson and Oliveira (2016).

Slaughtering and Trimming

Boiling water and scraping the pig’s hair. Reference: China on the Way.

Traditionally Xuanwei people kill the pigs usually before the last frost. They add boiling water to a wok and scrape the pig’s hair. Some people refer to killing the pig as washing the pig. For villagers, the killing of the pig is a sacred ceremony. (China on the Way)

The hind leg is trimmed into an oval shape in the form of a Chinese musical instrument, the pipa. The legs of small pigs are cut in the form of a leaf. The legs cut off along the last lumbar vertebra. After the blood is pressed out, the meat is held for ripening in a cold room at a temperature of 4 to 8 deg C, relative humidity of 75% for 24 hours. Ripened legs are known as green hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) This step is an enigma to me since I am not sure what is accomplished in such a short period of time. My guess is that it is not technically ripening, but rather allowing any excess fluids to drain out. I will keep interrogating the processing steps to ensure that my sources have the right information.

Cutting and trimming the leg: China on the Way.

Salting

The First Salting: China on the Way.

The green hams are then salted. The salt is a mixture of table salt (25g/kg of leg) and sodium nitrite (0.1g/kg leg). (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) The inclusion of sodium nitrite is without question a modern development since nitrite curing of meat only became popular after World War I. My instinct tells me that they originally only used salt and later, possibly, sodium nitrate, the production of which has been done for very long in Chinese history.

The salt is rubbed into the hams by hand massaging for around 5 minutes. “The salted hams are then stacked in pallets and held in a cold room at 4 to 8 deg C, 75 to 85% relative humidity for 2 days. Salting procedure is then repeated.” The salt ratios are this time changed to table salt of 30g/kg ham and sodium nitrite is kept at 0.1g/kg leg. The meat is rested for a further 3 days in the chiller after which another salting is done. The ratio of this salting is 15g of table salt per kg of ham and again, sodium nitrite is kept at 0.1g per kg ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Kneeing the hams as salt is rubbed in by hand: China on the Way.

According to Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei, “traditionally made hams are cured with half the salt used in factories. Instead, they are allowed to dry-cure for at least eight months to about three years, so the meat has time to mellow and mature.” “The longer the ham is cured, the better the quality and the most popular product now is the three-year-old cured ham.”

Double Salted Hams: China on the Way.

Drying

The hams are then hung in the drying room with a temperature of 10 to 15 deg C and relative humidity of between 50 and 60%. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) Note how the temperature is increased and the relative humidity decreases to facilitate drying from the inside, out.

The excess salt is brushed away and the hams are dried for 40 days. Windows are kept open to facilitate air movement to air drying. Screens are placed in front of openings to prevent flies, other insects and birds from entering. If drying is too fast, a crust will form on the outside of the ham and if it is done too quick, the inside will not be dried and will spoil. If drying is done too long, the meat will be too dry to accommodate the lactic acid bacteria which will be involved in the fermentation process.

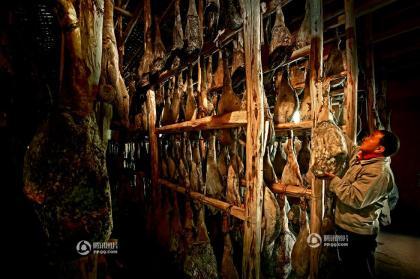

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei reports on the traditional way that drying was done. “If you visit the villages by Nujiang, you may chance upon a strange sight in winter, when the hams are hoisted high on trees so they can catch the best of the drying winds. These trees with hocks of ham hanging from them seem to bear strange fruit indeed.”

Fermentation

Drying and Fermentation: China on the Way.

After drying, the temperature is raised to 25 deg C. Relative humidity is pushed up to 70% and ideal conditions are created for fermentation. This process lasts for 180 days. Apart from creating an ideal condition for microbes, raising the temperature and humidity favours enzymatic activity, which is important in flavour development due to the partial decomposition of lipids (fat) and proteins. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Traditionally, the fermentation process takes more than ten months. When the surface is completely green, the hams are ready: China on the Way.

Aging

“Xuanwei ham is like good wine: the older the better. A ham that’s been aged at least 3 years can be eaten raw like prosciutto di parma.”

Control of Pests

During the curing and drying stages, flies pose a major risk. During fermentation and storage ham moths and mites (eg. tyrophagus putrescentiae) are the major danger. Relative humidity of over 80% attracts flies such as Piophila casei, Dermestes carnivorus beetle and mites. “There has been considerable work done in controlling mite infestation. Microorganisms such as the Streptomyces strain s-368 help prevent and treat mite investigation.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Evaluation

Bone needles or bamboo needles are used to insert it into three specific sites to check the ham. The smell tells the evaluator if the ham is ready: China on the Way.

Xuanwei hams are evaluated by sensory evaluation. The odor is absorbed by a bamboo stick, used for the evaluation. This is the most traditional absorption method to classify different ham grades. For a detailed discussion and evaluation of this method, see Xia, et. al (2017), Categorization of Chinese Dry-Cured Ham Based on Three Sticks Method by Multiple Sensory Techniques

Storage

Storage is done under ambient conditions and the hams can be stored between 2 and 3 years.

A caravan travelling along an ancient road. Pu Zaiting must have been driving just such a caravan, journeying from north and south: China on the Way.

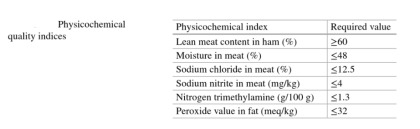

Physiochemical Indices

by Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016

“The physical and chemical properties of dry-cured ham are important determinants of its quality (Jiang et al. 1990 ; Careri et al. 1993 ). The lean portion of Xuanwei ham contains 30.4 % protein, 10.9 % fat, 10.3 % amino acids, 42.2 % moisture, and 8.8 % salt (Jiang et al. 1990 ). The whole ham contains 17.6 % protein, 29.1 % fat, 5.6 % amino acids, 24.8 % moisture, and 3.3 % salt (Jiang et al. 1990 ). Many essential elements are present in the ham as are some vitamins. The ham is particularly rich in vitamin E (45 mg/100 g). The characteristic bright red color of Xuanwei ham is mainly attributed to oxymyoglobin and myoglobin. The flavor and taste are associated with the presence of various amino acids and volatile organic compounds . The volatile substances present in Xuanwei ham have been extensively studied (Qiao and Ma 2004 ; Yao et al. 2004 ). Seventy-five compounds were tentatively identified in the volatile fraction. The compounds identified included hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, organic acids, esters, and other unspecified compounds.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Microflora

The dominant microorganism on the surface of dry cured hams is mold, which affects quality. During the ripening stage, molds play an important and positive role in flavour and appearance. A study of Iberian dry-cured hams showed that yeasts are predominant during the end of the maturing phase of production whereas Staphylococcus and Micrococcus are absent. This surface yeast population has been shown to be useful for estimating the progress of maturation. Its contribution to curing is suggested to be their proteolytic or lipolytic activity. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

In Xuanwei hams, researchers have shown Streptomyces bacteria to dominate and account for almost half of the Actinomycetes. Aspergilli and Penicillia are common on the surface of Xuanwei hams during June to August. They found 8 species of Aspergillus. A. fumigatus was found to be dominant and accounts for one third of Aspergilli. Generally speaking, a high relative humidity encourages mold development on the surface of the hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

The dominant fungi found on Xuanwei hams is yeast. Yeast can be 50% of the total microorganisms found on mature dry-cured hams. Proteolytic and lipolytic activity of yeast is desirable. Towards the end of maturation, yeast dominates on dry-cured hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Which species to be found during the different stages of production depends on temperature and relative humidity. In the Xuanwei region, humidity and temperature are highest during the rainy season. Molds occur almost exclusively on the surface of the hams. Aspergilli and Penicillia occur mostly during May when relative humidity and temperature are high. These fungi peak in July and August. Molds begin to grow in May and are well established by June. Spores are formed in August and September. The quantity of spores falls off gradually in September. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

“The growth of bacteria and Actinomycetes does not seem to be dependent on humidity in the curing room. Levels of bacteria are generally lower than levels of yeast. According to Wang, et al. (2006) yeast on ham multiplies exponentially from the beginning of the salting stage to reach a peak in April, and then the numbers drop and stabilise to around 2 x 107 cfu/g.Yeast levels within the ham show similar variation as the surface yeast. According to Wang et al. (2006) yeast accounts for 60 to 70% of the total microbial population on the surface of the ham. In some cases, no molds have been found growing on the surface of good-quality ham; therefore, some researchers believe that molds do not play a direct role in determining the quality of dry-cured ham, but an opposing view also prevails.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

“According to the traditional view, high quality Xuanwei ham must have “green growth” (i.e. molds) on it. However, fungi such as Penicillia , Fusarium , and Aspergilli are known to produce mycotoxin in foods such as dry-cured Iberian ham (Núñez et al. 1996 ; Cvetnić and Pepeljnjak 1997 ; Brera et al. 1998 ; Erdogan et al. 2003 ). More than 15 % of the mold strains examined were found to produce mycotoxins in Xuanwei ham (Wang et al. 2006 ). The toxins penetrated to a depth of 0.6 cm in the ham muscle. Because most of the fungi that occur on ham have not been examined for producing mycotoxins , contamination with toxins might be more prevalent than is realized.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Feasting

“The ham must be flame burned and washed before eating, in order to remove the rancid taste.” (China on the Way.)

Flame treatment: China on the Way.

There are an infinite variety of ways to serve the ham. It can be steamed, boiled, fried, or used as accessories. Old legs can be eaten raw. When cooking, cook either the whole ham or large cuts on a slow fire or slow boil it to retain the flavour.

China on the Way.

Further Reading

Traditional Foods, Kristbergsson, K., Oliveira

—————————————————————–

Reference

Adshead, S. A. M.. 1992. Salt and Civilization. Palgrave.

chinadaily.com Updated: June 26, 2019

China on the Way, XuanWei Ham

Flad, R., Zhu, J., Wang, C., Chen, P., von Falkenhausen, L., Sun, Z., & Li, S. (2005). Archaeological and chemical evidence for early salt production in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(35), 12618–12622. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0502985102

Huang, Christy. 2015. Old Towns of Yunnan, Heijing.

Kristbergsson, K., Oliveira, J. (Editors). 2016. Traditional Foods: General and Consumer Aspects. Springer.

Mew, T. W., Brar, D. S., Peng, S., Dawe, D., Hardy. B. (Editors). 2003. Rice Science: Innovations and Impact for Livelihood. International Rice Institute (IRRI).

Needham, J., Ping-Yu, H., Gwei-Djen, L.. 1980. Sivin, N.. Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Cambridge University Press.

SBS – http://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2017/04/30/over-1000-years-ham-heres-where-it-all-began

http://www.yunnanadventure.com/index.php/Attraction/show/id/153.html

https://yunnan.chinadaily.com.cn/2012-01/16/content_14500704.htm

http://www.chinaontheway.com/xuanwei-ham/?i=1

Xia, D., Zhang, D. N., Gao, S. T., Cheng, L., Li, N., Zheng, F. P., Liu, Y.. 2017. Categorization of Chinese Dry-Cured Ham Based on Three Sticks Method by Multiple Sensory Techniques Volume 2017, ID 1701756 https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1701756

Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ) Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ) Eben van Tonder 10 May 2020 Introduction Yunnan is one of China's premium food regions known for exquisite tastes.

0 notes

Text

Baijiu Ancient History

There are inscriptions mentioning a drink called li during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046BC) too, which scholars have attributed to be a drink similar to or actually, beer. However, during the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD), methods for actually distilling alcohol became pronounced and widely used. In the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD), Li Bai the poet mentions a spirit called Shaojiu and a Song Dynasty text from 982AD describes a distillation method that resembles modern day Baijiu, involving wheat and barley. It was during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368AD) that Baijiu began to spread and be popular amongst farmers and workers.

https://www.baijiublog.com/baijiu-history/

0 notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Dunhuang Mural

【Historical Artifacts Reference 】:

▶Woman Donor at Murals in Cave 114 of Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang China

————————

📸Photo:@摄影师梁咩咩

👗Hanfu: 青泠谷

🧚🏻Model&💄Stylist:@张小花

Post-production: @张小花

🔗Weibo:http://xhslink.com/XzpEhG

————————

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#hanfu history#漢服#汉服#中華風#china history#historical fashion#history

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Receptions: Why have depictions of lions changed over time?

In early Chinese culture the lion was seen as a divine and mythical beast. These earlier depictions were fanciful, often blended with other animalistic features. This hybridity is evident with the Qilin; a one horned, scaly, hoofed beast with the head and mane of a lion.

Live lions and lion pelts were traded along the silk road from c. 114 BC. Lions were a highly sought-after and rare commodity with only the very wealthy being able to afford live specimens. Most of these ended up in private estates. With access to lions being limited to an elite few, many artists had to rely on copying from earlier, imaginative representations.

Although still an expensive commodity, the sight of pelts may have been more common. Transporting a cart full of pelts would have been a considerably easier task than the transportation of one live lion over such a distance. Pelts however, display lions in a flattened form, they cannot convey its muscular tonality nor its posture, this may have been one cause of artistic misrepresentation.

A gradual change in the tradition can be observed by comparing depictions of lions during the Han (206BC-220AD) and Tang (618-907AD) Dynasty’s. The later Tang period having more realistic portrayals by artists and artisans, who, presumably, had more opportunity to observe the animal first-hand after centuries of lions being transported into the country. This could possibly provide one explanation as to why it took Chinese artists several centuries to formalise the appearance of lions. However, whilst later depictions eschewed the fantastical elements, the lion remained heavily stylised. The longevity of the tradition and the lion’s religious connotations were already heavily integrated into the Chinese culture as recognisable forms of ‘symbolic capital’ (Bourdieu, 1979), possibly surpassing eventual competency for mimetic accuracy through accessibility.

The relationship between the ‘lion’ and ‘stone’ is connected to the common Chinese tradition of using puns and word play to group or associate objects. The word for lion and stone is the same, Shi, the only difference being the phonetic stress on each word, Shíshī. This relationship between object and material is evident within its long historical association. Lions being used as ‘stone guardians’ to tombs, pre-dates the first records of live lions arriving in China.

Comparing Western sculptures of lions to Chinese examples from the same era highlights this aesthetic difference. Chinese depictions portrayed lions as symbolic in opposition to Western mimesis. Interestingly, the influence of Chinese sculpture can also be observed in the Western statues, where the lion also has a ball under its paw. The Romans were masters of cultural appropriation and it is more than likely that they ‘borrowed’ this feature from their Eastern trade partners. In China this ball symbolises that this lion is male and its spiritual qualities. The ball under the foot of this Roman example, the famous ‘Medici Lion – c. 2AD’ has a very ambiguous explanation on its Wikipedia page, ‘a ball, possibly a globe’, the ball has no meaning in Western culture. Foucault describes this phenomenon as ‘repeatable materiality’ where statements and symbols from one culture can be reinterpreted and transcribed in the discourse of another.

Medici Lion (Rome):

Guard Lion (China):

0 notes

Link

The Chongyang Festival (or Chung Yeung Festival) is also known as the Double Ninth Festival as it falls on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month this year (Oct 7). According to the ancient Chinese divination text I Ching, this Double Ninth day has too much yang (active energy) and is therefore a“potentially dangerous day”.

Traditionally, people climb mountains, drink chrysanthemum wine, and carry the zhuyu (dogwood) plant for protection. Folks also go to parks to enjoy the beauty of chrysanthemums as the flower symbolises longevity. Drinking chrysanthemum wine is believed to ward off evil and block off disasters. The scent of the chrysanthemums and zhuyu is also said to repel insects and keep out the cold.

Although this annual festival is not celebrated in Malaysia, it is a traditional holiday celebrated in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. In China, nine has a similar pronunciation to the word “forever”, which symbolises longevity.

In 1966, Taiwan rededicated this day as Senior Citizens’ Day. In 1989, the Chinese government also set this day as Seniors’ Day. Activities are held to show respect and appreciation towards seniors, such as sending them gifts and on trips. In Hong Kong, families visit their ancestral graves on this day.

The Japanese celebrate the Double Ninth Festival (Sept 9 on the Gregorian calendar) known as choyo and the Chrysanthemum Festival at Shinto and Buddhist shrines. It is one of Japan’s five sacred ancient events and is celebrated as a wish for longevity. People drink chrysanthemum sake, eat chestnut rice (kuri-gohan) and chestnuts with glutinous rice (guri-mochi).

Koreans also celebrate Double Ninth on Sept 9. Their festival is known as jungyangjeol. They eat pancakes with chrysanthemum leaves, carry dogwood, and cultivate good health by participating in outdoor activities like climbing hills and mountains for picnics, or gazing at chrysanthemum blossoms in parks.

Water to boost relationships

Feng shui master Yap Boh Chu.

Malaysian feng shui master Yap Boh Chu said the Double Ninth Festival is “a semi-auspicious day”. “It is a good day to demolish a building,” he said. “However, it is a bad day for burial and burning of the memorial tablet in Taoist memorial services.”

Yap explained this is because it is believed that the luck of the descendants will be affected. His advice is not to disturb the southwest sector of the house. “It is extremely bad to do anything in this sector as this can lead to sickness and accidents.”

However, if the north sector of your house has a water element, it is a sign that it is good to start a relationship. “If not, you can enhance your relationship by placing a bucket of water in this sector and changing it every day for five days only.”

History and legend

The origin of Chongyang dates back over 2,000 years to the Warring States period (475BC-221BC) in China, when the festival was held in the palace. It was celebrated by the public during the Han Dynasty (202BC-220AD) and was known as Chongyang during the Three Kingdoms period (220-280AD).

The custom of celebrating the day by enjoying chrysanthemum and drinking wine is believed to have originated during the Jin Dynasty (265-420AD). It was officially set as a festival during the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD). In the Ming and Qing dynasties, flower cakes were eaten to celebrate the event, and the emperor climbed the mountain on this day.

Folks enjoying the beauty of chrysanthemums as the flower symbolises longevity.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220AD), people would fall ill and die whenever a devil – some say, monster – in the Ruhe River emerged. A man named Huan Jing survived, but his parents died because of this.

After his recovery, he sought an immortal’s help to vanquish the demon and was given zhuyu leaves and chrysanthemum wine. Huan Jing distributed the leaves and wine to the people. On the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, the creature emerged from the river but became dizzy when it smelt the zhuyu and flowers. Huan Jing drew his sword and killed it.

According to another version of the myth, on the Double Ninth day, a man named Heng Jing advised his countrymen to hide on a hill while he battled a monster. When the monster was killed, the people held a victory celebration on that day.

from Family – Star2.com https://ift.tt/30Neqa1

0 notes

Text

618-907AD CHINESE TANG Dynasty Authentic Ancient Antique Cash Coin CHINA i77218

http://dlvr.it/R2JvVm

0 notes

Text

Tea 101: Origination Part 1 The Legends

"Tea has a long and turbulent history, filled with intrigue, adventure, fortune gained and lost, embargoes, drugs, taxation, smugglers, war, revolution, religious aestheticism, artistic expression, and social change." Mary Lou & Robert J. Heiss (The Story of Tea)

The history of tea is slippery. Its origin stories are street-wise and nimble; nailing down a single tale feels a bit like unravelling knotted necklace chains, coiled together at the bottom of your suitcase. The rich history of tea is multi-storied, but I've sifted out two to get us started.

In the beginning...

The Legend of ShenNong (2737 BC)

Once upon a (prehistoric) time, in a land far far away (unless you are in China) lived the legendary deity, Shennong. Shennong was a mythical sage ruler, and the mastermind behind Chinese agriculture and medicine. One windy day, he was drinking a bowl of boiled water (all the subjects of the land cleansed their water by boiling it first) and a few leaves blew into the cup, changing the colour. The emperor took a sip of the brew, and was pleasantly surprised by its flavour. Some tell a variant of the legend, in which Shennong tested the medicinal properties of teas on himself, and found them to soothe ailments and work as an antidote to poisonous herbs. (For more on this legend and others, check out Lu Yu's famous early work on the subject, The Classic of Tea.)

The Legend of Bodhidarma (Tang Dynasty 618 - 907AD)

*sometimes, another version of the story is told with Gautama Buddha in place of Bodhidharma.

Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China. According to Chinese legend, he also began the physical training of the monks of Shaolin Monastery, which led to the creation of Shaolin kungfu. In Japan, he is known as Daruma. The rather gruesome legend dates back to the Tang Dynasty. In the traditional folklore, Bodhidharma accidentally fell asleep after meditating in front of a wall for nine years. He woke up in such disgust at his weakness, that he cut off his own eyelids. They fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes. This myth expresses the sentiment that tea is the drink of woke-folks: open eyes as a metaphor for staying present, engaged, and aware in the world.

So there you have it, the first two pieces of a tea leaf puzzle. Origin stories shape our collective consciousness, and function as a container for growing. Share below if you know another version of the tale!

Much love and tea-stained fingertips,

Vanessa

0 notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Dunhuang Mural

【Historical Artifacts Reference 】:

China Tang Dynasty Dunhuang Mural: