#Richard Rorty

Quote

Before Kant, an inquiry into "the nature and origin of knowledge" had been a search for privileged inner representations. With Kant, it became a search for the rules which the mind had set up for itself (the "Principles of the Pure Understanding"). This is one of the reasons why Kant was thought to have led us from nature to freedom. Instead of seeing ourselves as quasi-Newtonian machines, hoping to be compelled by the right inner entities and thus to function according to nature's design for us, Kant let us see ourselves as deciding (noumenally, and hence unconsciously) what nature was to be allowed to be like. Kant did not, however, free us from Locke's confusion between justification and causal explanation, the basic confusion contained in the idea of a "theory of knowledge."

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#Kant#belief#representation#justification#causality#knowledge#epistemology

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

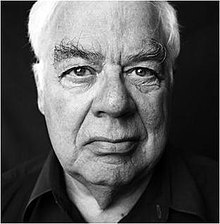

One time—it was the only time I ever taught Lolita!—I assigned a chapter from this book and used the cover, specifically Rorty's facial expression, to explain his philosophy. The tight smile on his face represents his amused resignation to the contingency and irony of the world as celebrated by such playful authors as Nietzsche, Derrida, and Proust, while the unmistakable sorrow in his eyes shows his knowledge of the suffering in the world and the consequent need for solidarity, as called for by such writers as Marx and Mill, Dickens and Orwell—a synthesis of smiling mouth and haunted eyes recapitulated in the subliminally mournful hijinks of Lolita itself. I don't remember if the students were persuaded. I didn't know it when I made the syllabus, but they were all PSEO students and therefore about 16 years old, so, between being assigned Lolita and hearing this kind of thing, I think they were just in a state of, "Whoa...college."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

phenomenological epigraphy

Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin

also, Sartre’s ocularphobia

#Juhani Pallasmaa#The Eyes of the Skin#johann wolfgang von goethe#friedrich nietzsche#richard rorty#jorge luis borges#maurice merleau ponty#jean paul sartre

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

«La concepción que estoy presentando sustenta que existe un progreso moral, y que ese progreso se orienta en realidad en dirección de una mayor solidaridad humana. Pero no considera que esa solidaridad consista en el reconocimiento de un yo nuclear —la esencia humana— en todos los seres humanos. En lugar de eso, se la concibe como la capacidad de percibir cada vez con mayor claridad que las diferencias tradicionales (de tribu, de religión, de raza, de costumbres, y las demás de la misma especie) carecen de importancia cuando se las compara con las similitudes referentes al dolor y la humillación; se la concibe, pues, como la capacidad de considerar a personas muy diferentes de nosotros incluidas en la categoría de “nosotros”. Esa es la razón por la que he dicho, en el capítulo cuarto, que las principales contribuciones del intelectual moderno al progreso moral son las descripciones detalladas de variedades particulares del dolor y la humillación (contenidas, por ejemplo, en novelas o en informes etnográficos), más que los tratados filosóficos o religiosos.»

Richard Rorty: Contingencia, ironía y solidaridad. Ediciones Paidos, pág. 210. Barcelona, 1991

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#richard rorty#rorty#contingencia#ironía y solidaridad#moral#progreso moral#ética#solidaridad#yo#yo nuclear#esencia humana#nosotros#diferencia#diferencias#“nosotros”#dolor#humillación#novela#novelas#literatura#etnografía#tratados etnográficos#concepciones universalistas#concepciones esencialistas#concepción historicista#teo gómez otero

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A tényrelativizmus mérése Magyarországon

A Political Capital közölt egy tanulmányt (itt érhető el), amiben arra keresik a választ, hogy „a tényrelativizmus jelensége hogyan jelenik meg a hazai közvéleményben”. „Tényrelativizmus” alatt pedig „a tények létezésével és megismerhetőségével kapcsolatos erősödő kételyt” értik a szerzők.

Ezt a fajta tényrelativizmust úgy gondolják a média iránti bizalmatlanság váltja ki. Magyarországon a bizalom a média iránt rendkívül alacsony: „A médiába vetett bizalmatlanság vonatkozásában Magyarország az élvonalba tartozik: mindössze 25% bízik a médiában, ami a Reuters Intézet kutatása alapján a második legalacsonyabb arány az általuk vizsgált 46 országot felölelő globális mintán.”

A kutatásban öt állítás esetében kérdezték meg az embereket mennyire értenek egyet az adott állítással. Egytől ötig terjedő skálán lehetett válaszolni, ahol az egyes az „egyáltalán nem ért egyet”, az ötös a „teljes mértékben egyetért”. Minél magasabb pontszámot „ér el” így az ember, annál inkább tekintik a kutatásban tényrelativistának az illetőt.

Érdekesnek találom, hogy végső soron egy filozófiai álláspont elterjedtségét próbálja a tanulmány mérni ezért, arra gondoltam írok néhány megjegyzést az állításokhoz, amikről az embereket kérdezték.

Nem lehetünk biztosak abban, hogy amit tényként közölnek, az igaz is.

Ez egy triviális 5 pontos kérdés, teljesen magától értetődő, hogy ha valaki valamit tényként közöl, attól még tévedhet, vagy hazudhat. Nem értem ez miért mozdítana bárkit is a tényrelativizmus felé. Ugyanakkor nem tisztázott, hogy ki közli a feltételezett tényt: ha megbízhatónak tekintem a forrást, inkább fogom elhinni. Ez az állítás szerintem nagyon rossz, mert szerintem szimplán józan ész ezzel egyetérteni.

Sok dolog, amire tényként hivatkoznak a sajtóban, valójában csak egy vélemény.

Itt úgy érzem, nagymértékben befolyásolhatja a válaszadókat az, hogy kifejezetten a sajtóban hivatkozott dolgokra szűkítették az állítást. Kíváncsi vagyok, ha úgy fogalmazták volna meg, hogy „Sok dolog, amire tényként hivatkoznak, valójában csak egy vélemény.” milyen eredmény született volna. Felmerül a kérdés, mit akarunk mérni? A tényrelativizmus, mint filozófiai gondolkodás elterjedtségét, vagy a médiába vetett bizalmat? Ha az előbbit, akkor a módosított kérdést kellene feltenni, ha az utóbbit, akkor jó így. Azonban ha valaki azt állítja, hogy aki a fenti állítással egyetért, tényrelativizmusról tesz tanúbizonyságot, annak szerintem azt lehet válaszolni, nem, pusztán szkeptikus a sajtó megbízhatóságát illetően.

A „sok dolog” kifejezés is érdekes az állításban, mert ha valaki valóban tényrelativista, akkor bármi, amire tényként hivatkoznak valójában vélemény, hiszen tények egyáltalán nincsenek. Egy tényrelativista lehet, épp azért nem értene egyet ezzel az állítással, mert nyitva hagyja a lehetőségét annak, hogy bár sok dolog vélemény és nem tény, azért lehet, hogy van olyan, ami tény és nem vélemény, csak kevés ilyen van.

Az „igazság” valójában az az álláspont, amit az ember magának választ.

Ezt az állítást vegyük kétfelé: a, Az „igazság” az álláspontunk függvénye; b, Ezt az álláspontot az ember önkényesen magának választja. Ugyan az eredeti állítás nem tartalmazza az „önkényes” kifejezést, én azért tettem itt bele, mert úgy gondolom, hogy igazából erre vagyunk kíváncsiak, hogy az emberek úgy gondolnak-e az igazságra, mint amit mindenki magának tud eldönteni, bármi másra tekintet nélkül. Tegyük fel, hogy elfogadjuk a-t, de elutasítjuk b-t, és azt mondjuk az igazság az álláspontunk függvénye, de ez az álláspont nem egy egyénileg, önkényesen meghozott döntés, hanem egy közösségileg ellenőrzött döntés. Nem pusztán arra gondolok, hogy a többség álláspontja lesz elfogadva, hiszen nem is így éljük mindennapjainkat: gyakran hagyatkozunk egy szakértő kisebbségre (helyesen) olyan speciális esetekben, ami szakértelmet igényel (orvosok, fizikusok, stb). Aki így gondolkodik, az például el fogja fogadni a tudomány jól megalapozott állításait igaznak, mert azt mondja, a tudományos álláspont a legmegbízhatóbb, ami jelenleg elérhető. De mivel a tudományt emberek művelik, sosem leszünk olyan helyzetben, hogy kijelentsük, hogy ez most már a „végső” igazság. Ha valaki elfogadja a-t és b-t is, az joggal nevezhető tényrelativistának, hiszen ez az ember azt gondolja, hogy az igazság egyénileg, önkényesen eldönthető, mindenféle konzultáció nélkül másokkal. Aki valóban tényrelativista erre a kérdésre 5 pontot kell, hogy adjon. Aki tény realista 1-et, és aki a fenti gondolatmenettel egyetért, az vagy nem válaszol, vagy valami köztes értéket fog választani.

Objektív valóság valójában nem létezik, csak különböző vélemények vannak.

Szerintem a ki nem mondott feltevés az állítás hátterében az, hogy ha nincs objektív valóság, akkor nem lehetünk kritikusok senki véleményével kapcsolatban, hiszen nincs olyan neutrális álláspont, amiből el lehetne dönteni, kinek van igaza. Ez az állítás egy fals dichotómia. Nem úgy kritizálunk másokat, hogy mi birtokában vagyunk az objektív valóság ismeretének, és ez alapján meg tudjuk mondani, hogy ki téved és ki nem. Mi ugyanúgy tévedhetünk, szóval az „objektív valóságra” való hivatkozás felesleges. Amikor vélemények ütköznek, akkor mindkét fél feladata az, hogy érvekkel támassza alá, hogy miért gondolja igaznak, amit mond. Ha valaki azt mondja: „nekem van igazam, mert ez az objektív valóság”, akkor igazából semmilyen érvet nem hozott fel. Ez csak egy retorikai fogás, amivel bárki élhet. A kérdés az, szükségünk van-e egy „objektív valóság” feltételezésére, mint egy vezérfonálra. Richard Rorty a mellett érvel, hogy nincs (Richard Rorty : „Is Truth A Goal of Enquiry? Davidson Vs. Wright”). Nem tudom eldönteni mikor értem el az „igazságot”, ezért nem is tudom „megcélozni” az igazságot. Amit tudok az az, hogy kellően jól igazoltak-e a hiteim, amit úgy tudok elérni, hogy mások véleményét is kikérem. Nyilván nagyon alapvető dolgokat le tudok ellenőrizni magam is, de bonyolultabb tudományos állításoknál szükség van egy tudósokból álló közösségre, akik megpróbálnak kritizálni elméleteket, reprodukálni kísérleteket, vagy új kísérleteket kitalálni. Aki tényrelativista 5 pontot fog adni erre az állításra, aki tény realista 1-et, de azt szeretném megmutatni ennél az állításnál, hogy nem csak ez a két lehetőség létezik. Ez az állítás a szekuláris változata annak, hogy „Isten nélkül mindent lehet”, ami már kiderült, hogy egy hibás elképzelés volt, és erről az állításról is szerintem ki fog derülni, hogy téves.

Aki azt állítja, hogy tudja mik a tények, valójában hazudik.

Furcsa az állítás, mert nem engedi meg, hogy az illető, aki azt állítja, tudja, mik a tények egyszerűen téved. Nem tudom, ez az állítás mennyire jól méri az emberek tényrelativizmus hajlamát. Még ha tény relativista is vagyok, nem feltétlenül kell azt mondanom, hogy aki ezt állítja, hazudik, és nem egyszerűen csak téved. Például, mert meg lett vezetve, és azt hiszi, hogy tények léteznek. Így akár 1 pontot is adhatok rá.

Mennyire tűnnek az állítások jónak a tényrelativizmus felmérésére? Az első állítás triviálisan elfogadható, és semmilyen tényrelativizmusra nincs szükség, hogy egyetértsünk vele. A második állítás inkább a sajtó iránti bizalmat tükrözi, mint a tényrelativizmust. A harmadik és negyedik állítások jó szűrőnek tűnnek alapvetően. Az ötödik megint nem tűnik jónak, mert nem engedi meg, hogy a tényeket állító személy egyszerűen tévedett. Szóval összességében ötből három állítás nekem nem tűnik alkalmasnak a tényrelativizmus mérésére. Illetve nekem úgy tűnik, hogy a kutatás készítői feltételezik a négyes állításban levő fals dichotómiát, miszerint vagy hiszünk a tények objektivitásában, vagy relativisták vagyunk, és nincs más lehetőség. Az írásomban azt szerettem volna bemutatni, hogy nem csak ez a két út lehetséges.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

#richard rorty#richard mckay rorty#rorty#philosophy#pragmatism#philosophy of language#postphilosophy#philosophy of mind#inna besedina#historyandphilosophy

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

[5:55] Rorty: “I’ve never been very easy in my dealings with people ...”

[6:30] According to my parents I pretty much taught myself to read when I was four ... and spent most of the rest of my life reading books.

Interviewer: the world in those books. Was it more important to you?

Rorty: Yeah, much more important.The world outside never quite lived up to the books - except for a few scenes in nature. You know, animals, birds, flowers.

Interviewer: What kind of world we're creating by reading books and combining them what kind of picture...?

Rorty: Oh, fantasies of power. Control. Omnipotence. Sort of usual childhood fantasies. Turning out to be the unacknowledged son of the king that kind of thing.

Interviewer: Power through the control - the power you missed in the schoolyard.

Rorty: Yeah. And I think basically I was looking for some way to get back at the schoolyard bullies by turning into some kind of intellectual and acquiring some kind of intellectual power though. I wasn't quite clear how this was going to work.

Interviewer: Did you manage to come back to them as the intellectual?

Rorty: No, I just lost touch with them by living in a world of intellectuals.

---

[8:50]

Interviewer: How’d you become a philosopher?

Rorty: I think philosophy was somewhat accidental, I think that I could equally could’ve become an intellectual historian or literary critic. But it just happened that the course that I was most intrigued by when I was 16 was a philosophy course. So I sort of kept taking more and more philosophy courses and signing up for more and more degrees.

Interviewer: Why were you intrigued?

Rorty: I think because of the sense of mastery and control that you get out of philosophical ideas. You get the impression from reading philosophy that now you can place everything in an order or a neat arrangement. Or something like that. This gratifies one’s need for domination -

Interviewer: - and compensation of the shyness?

Rorty: Yeah.

Interviewer: I remember that there are many people participating in consolation. If I asked them, what is consolation ... they come up with the sense of order. The sense to have the whole chaotic world in your hand, to control it, to name it...

Rorty: I guess I don't associate that with beauty. I think of it as something much more like power ... I think of beauty as sensuous, and philosophical ideas in the usual cliched terms: cold, hard, abstract.

---

[10:52]

Interviewer: What were you critically discovering the time you went into philosophy? Because you had the illusion of having power,

Rorty: Well I was hoping to, anyway, by reading enough philosophy. When I was 16, I read through Plato thinking, you know, if I read everything in Plato, I would sort of get the, the essential Plato and be in command of this sprawling mess of dialogue. And of course, it didn't work out that way because Plato was too good an author to let himself be controlled, but it was a good try.

And then I just kept on going, reading, reading philosophy books, until it was too late to do anything else. When I was 20, I had a master's in philosophy and couldn't think of anything to do except take it to Oxford. And then once I got a doctorate in philosophy, there wasn't much to do except teach philosophy.

Interviewer: But you wanted to be in control. You were the shy boy from school, still...

Rorty: Yes.

---

[12:07]

Interviewer: When did you realize you shouldn’t have...?

Rorty: Oh, sometime in my 20s when I began to think that philosophical ideas were, so to speak, ingenious artifacts rather than levers of power.

Interviewer: Was this a dramatic moment because I can imagine if you have your illusions about philosophy as a kind of ‘ordering the world’ and to lead your own chaotic world, to have any on hand to discover that you're just playing with toys and not -

Rorty: it's not exactly just - it wasn't the sense of just playing with toys. But having the feeling that philosophical systems were more like, writing sub systems was more like contributing to a literary genre than, like, assuming command of the universe. And no it wasn't anything very sudden. I mean, just somewhere between the age of 20 and the age of 35. I couldn't tell you where.

Interviewer: And what happened once you realized it didn't say ‘I quit.’

Rorty: No. I mean, it was my bread and butter.

Interviewer: But is it that simple?

Rorty: Sure, I mean. Teaching philosophy is a very agreeable occupation. You get a lot of spare time it pays well, you can do pretty much what you want, especially after you get tenure. It never occurred to me to totally change my life. But I began writing somewhat different kinds of stuff. And eventually it got more and more different as the years went by. I never found philosophy books consolatory - except in the sense of occasionally being overwhelmed by a surge of admiration for a particular philosophical work and thinking ‘what a what a brilliant imagine the creation. How nice to be in the same world where people can create something like this, and to be able to appreciate what they've done.’

Interviewer: But, this is not consolation ...?

Rorty: Yeah, it's not consolation for loss or despair or anything. It's just consolatory works tend to be poetic or fictional achievements more than philosophical works.

---

[21:09]

Idon't want to talk about the uncertainty inherent in the life of every human being I mean some human beings leadquite certain predictable lives you know people in traditional societies peoplein such miserable conditions that they have to work 14 hours a day and sleep the rest now there isn't muchuncertainty around and I think that uncertainty in the sense in whichphilosophers dramatize uncertainty is a luxury it's the kind of thing you candeliberately induce in yourself for the sheer thrill of it by reading lots ofdifferent books and being uncertain about which are them to believe

---

[22:37] Greek (Platonic philosophy) vs pragmatic philosophy

The Greek idea is that at a certain point in the process of inquiry you come to rest because you've reached the goal. And the pragmatists are saying we haven’t the slightest idea what it would be like to reach the goal. The idea that the aim of inquiry is correspondence to reality, or seeing the face of God, or substituting facts for interpretations, is one that we just can't make any use of. All we really know about is how to exchange justifications of our beliefs and desires with other human beings, and as far as we can see that will be what human life will be like forever. So pragmatists regard the Platonist attempt to get away from time into eternity or get away from conversation into certainty as a product of an age of human history where life on earth was so desperate and it seems so unlikely that life could ever be better that people took refuge in another world. Pragmatism comes along with things like the French Revolution Industrial Technology - all the things that made the 19th century believe in progress. When you think that the aim of life is to make things better for our descendants rather than to reach outside of history and time, it alters your sense of what philosophy is good for. In the Platonist and theistic epoch, the point of philosophy was to get you out of this mess into a better place - God, the realm of Platonic ideas the kind of the contemplatively something like that and the reaction against this Greek-Christian pursuit of blessedness through union with a natural order is to say there isn't any natural order but there is the possibility of a better life for your great-great-great-grandchildren. And that's enough to give you all the meaning or inspiration you need.

---

[24:58]

Hans Bloomberg had a remark that impressed me enormously. said at some point we stopped hoping for immortality and in place started hoping for our great-great-grandchildren. You know this was a sort of turn in the culture of the West, and you know, I really believe that. I think that it had to do with simple improvement of material conditions. When we got a comfortable bourgeois existence for large numbers of people the bourgeois was able to think not about escapefrom the world and pie-in-the-sky but about creating a future world for future mortals. That seems to me a great improvement.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Do We Need Ethical Principles? Richard Rorty (1994)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

being a person whose first instinct is to categorize and analyse everything logically in a stereotypical sense of the word and at the same time being aware that the Truth "isn’t out there", somewhere in the world objectively, is truly a curse

#like i cannot explain to people how my brain works#like i can give a justification for something but it will never be enough#truth is only in sentences babey#richard rorty#friedrich nitzsche#philosophy#epistemology#philosopher problems lmao#3 am thoughts#insomnia ramblings#mine#philosophy textpost

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[Epistemology] is supposed to explain how knowledge is possible, and to do that in some a priori way which both goes beyond common sense and yet avoids any need to mess about with neurons, or rats, or questionnaires. Given these somewhat exiguous requirements and no knowledge of the history of philosophy we might well be puzzled about just what was wanted and about where to begin. Such puzzlement can only be alleviated by getting the hang of terms like "Being versus Becoming," "sense versus intellect," "clear versus confused perceptions," "simple versus complex ideas," "ideas and impressions," "concepts and intuitions." We will thereby get into the epistemological language-game, and the professional form of life called "philosophy."

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#epistemology#knowledge#justification#language

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Consequences of Pragmatism#Rorty#life#self#being#internality#knowledge#belief#faith

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope Tumblr can forgive the piquant way these Twitter anons phrase some things, because the above mapping is basically correct, except that the phenomenon mapped is bigger than America's recent generational divides—bigger, in fact, than America. I give you, for example, the peroration of an article by friend-of-the-blog Nancy Armstrong. The article was published in 2001, before social media and when the Zoomers were still in the cradle. Armstrong's polemical target is Richard Rorty, whom she likens to the Victorian English liberals Mill and Arnold, seeing all three as panicked by the encroachment of popular heterogeneity upon the sphere of a unified national culture, whether late-19th-century English culture or late-20th-century American culture. For the purposes of anon's framing, Rorty (b. 1931) is a Boomer and Armstrong (b. 1938) is a Zoomer, but, as you see from the dates, that can't be right. What anon takes to be American Zoomer ideology goes back at least to the first Late Victorians who rebelled against Arnold (Mill/Arnold = Boomers; Pater/Wilde = Zoomers), themselves the distant founders of our queer politics defined by the separation of sign (gender) from referent (body), which, as anon rightly says, have become the power politics of empire today in a world-historical incidence of what I have in a narrower but related circumstance traced as the path "from counterculture to hegemony."

In our present cultural milieu, it is even less practical to believe that the cultural turn can be reversed by detaching politics from culture and restoring the mimetic priorities of old-fashioned realism than to long for the aesthetic autonomy of New Criticism or look for hope in the inspirational works of our literary tradition. To come to this conclusion is to admit that any responsible political action rests on understanding the degree to which the world we inhabit actually depends on the way that we read and represent the things and people in it. Changing an established world picture is an admittedly monumental task that may well begin and end in the literary classroom. But precisely because our Victorian forebears were so successful in establishing their picture of the world as the world itself, the fantasy that one can remake one’s culture through criticism is not only a legacy that they bequeathed to us. That fantasy also offers an effective means of displacing the picture of a world divided into homogeneously populated nations that our Victorian forebears worked so hard to put in place. The crises that arise when that old ideal of the nation is severely challenged do not disrupt or threaten American culture. Our culture is a culture in crisis, and some of us like it that way.

—Nancy Armstrong, "Who's Afraid of the Cultural Turn?" differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 12.1 (2001)

#nancy armstrong#richard rorty#cultural studies#cultural criticism#john stuart mill#matthew arnold#walter pater#oscar wilde#literary theory

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind, 1956

The most important work by one of America’s greatest twentieth-century philosophers, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind is both the epitome of Wilfrid Sellars’ entire philosophical system and a key document in the history of philosophy. First published in essay form in 1956, it helped bring about a sea change in analytic philosophy. It broke the link, which had bound Russell and Ayer to Locke and Hume—the doctrine of “knowledge by acquaintance.” Sellars’s attack on the Myth of the Given in Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind was a decisive move in turning analytic philosophy away from the foundationalist motives of the logical empiricists and raised doubts about the very idea of “epistemology.”

With an introduction by Richard Rorty to situate the work within the history of recent philosophy, and with a study guide by Robert Brandom, this publication of Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind makes a difficult but indisputably significant figure in the development of analytic philosophy clear and comprehensible to anyone who would understand that philosophy or its history. (Harvard University Press)

Wilfrid Sellars (1912–1989) graduated from the University of Michigan in 1933. He taught at Iowa, Minnesota, and Yale, and was University Professor of Philosophy at the University of Pittsburgh from 1963 until his death. His works include Science and Metaphysics (1968) and Science, Perception, and Reality (1963).

Richard Rorty (1931–2007) authored several landmark books and essay collections, including Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature; Consequences of Pragmatism; Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity; and Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. He taught at Wellesley College, Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and Stanford University.

Robert B. Brandom is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the University of Pittsburgh and a Fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the British Academy. He delivered the John Locke Lectures at the University of Oxford and the Woodbridge Lectures at Columbia University. Brandom is the author of many books, including Making It Explicit, Reason in Philosophy, and From Empiricism to Expressivism. (Harvard University Press)

I'm attaching a link to b u y the text. Note: attached text is not Rorty and Brandom's 1997 edition.

http://www.ditext.com/sellars/epm.html

#wilfrid sellars#richard rorty#robert brandom#empiricism and the philosophy of mind#50s#to read#modern philosophy#philosophy resource#philosophy texts#american philosophy

0 notes

Quote

Always strive to excel, but only on weekends.

Richard Rorty

#quote#quotes#dailyquote#dailyquotes#themedquote#themedquotes#kawttonkandii#saturday#weekend#weekendquote#weekendquotes#theweekend#richard rorty#excel#strive

1 note

·

View note