#Regret: Of all the objects our lords left behind there are none so worthless as these oracles! They know nothing of the great journey!

Text

Me tormenting the captive borrower with infodump rants

#g/t#Cortana: What is that?#Gravemind: I? I am a monument to all your sins.#Arbiter: *struggling*#Master Chief: Relax I'd rather not piss this thing off.#Arbiter: Demon...#Gravemind: This one is machine and nerve and has its mind concluded.#This one is but flesh and faith and is the more deluded.#Arbiter: Kill me or release me parasite but do not waste my time with talk.#Gravemind: There is much talk and I have listened through rock and metal and time#now I shall talk and you shall listen.#2401 Pentinent Tangent: Greetings! I am 2401 Pentinent Tangent. I am the monitor of installation 05.#Regret: And I am the Prophet of Regret...councilor most high... hierarch of the covenant.#2401 Pentinent Tangent: A reclaimer? Here? At last! We have much to do. This facility must be activated if we are to control this outbreak.#Regret: Stay where you are! Nothing can be done until my sermon is complete!#2401 Pentinent Tangent: Not true. This installation has a successful utilization record of 1.2 trillion simulated and one actual.#it is ready to fire on demand.#Regret: Of all the objects our lords left behind there are none so worthless as these oracles! They know nothing of the great journey!#2401 Pentinent Tangent: And you know nothing about containment! You have demonstrated complete disregard for even the most basic protocols!#Gravemind: This one's containment *shudders in disgust* and this one's great journey are the same.#Gravemind: Your prophets have promised you freedom from a doomed existence but you will find no salvation on this ring.#Those who built this place knew what they wrought. Do not mistake their intent or all will perish as they did before.#Master Chief: This thing is right. Halo is a weapon your prophets are making a big mistake.#Arbiter: Your ignorance already destroyed one of the sacred rings Demon in shall not harm another.#Gravemind: If you will not hear the truth then I will show it to you.#There is still time to stop the key from turning but first it must be found.#Gravemind: *gestures to Master Chief* You will search one likely spot *gestures to the Arbiter* and you will search another.#Gravemind: Fate had us meet as foes but this ring will make us brothers.#was gonna do the part where master chief gets teleported to high charity but I ran out of tags

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Noiseless Land

Anthropologists describe societies of this sort as possessing a ‘double morphology’. Marcel Mauss, writing in the early twentieth century, observed that the circumpolar Inuit, ‘and likewise many other societies . . . have two social structures, one in summer and one in winter, and that in parallel they have two systems of law and religion’. In the summer months, Inuit dispersed into small patriarchal bands in pursuit of freshwater fish, caribou, and reindeer, each under the authority of a single male elder. Property was possessively marked and patriarchs exercised coercive, sometimes even tyrannical power over their kin. But in the long winter months, when seals and walrus flocked to the Arctic shore, another social structure entirely took over as Inuit gathered together to build great meeting houses of wood, whale-rib, and stone. Within them, the virtues of equality, altruism, and collective life prevailed; wealth was shared; husbands and wives exchanged partners under the aegis of Sedna, the Goddess of the Seals.

--”How to Change the Course of Human History,” Graeber & Wengow

One of the schools of Tlön goes so far as to negate time: it reasons that the present is indefinite, that the future has no reality other than as a present memory. Another school declares that all time has already transpired and that our life is only the crepuscular and no doubt falsified an mutilated memory or reflection of an irrecoverable process. Another, that the history of the universe - and in it our lives and the most tenuous detail of our lives - is the scripture produced by a subordinate god in order to communicate with a demon. Another, that the universe is comparable to those cryptographs in which not all the symbols are valid and that only what happens every three hundred nights is true. Another, that while we sleep here, we are awake elsewhere and that in this way every man is two men.

--Borges

Report of Shurnamma Tirigan, former Captain of the Southern Expedition, 12 Ezenamarsin, 1674 AUC:

To the Lord Librarian of the City, Izaru Mahash, salutations and greetings; and may Bright Uru prosper forever. If you please, convey at your earliest convenience my greetings and my love to my nieces and nephews, and to your own husband and daughters.

I was dispatched by order of the Assembly to visit the southern countries beyond the Išaru Peninsula and Wormsgate, these far-off lands being little traveled by our countrymen, and there being some hope of establishing outposts on those shores for the purposes of trade with their people, and perhaps even for expanding our Empire. I have composed this message in the hopes of recording what transpired on this voyage, both as a matter of intelligence for the Library and the Assembly, and for the interest of Lord Mahash herself, who has expressed in the past eagerness for news of distant lands and nations.

We voyaged from the City along the coast for nine weeks, until a storm came up suddenly on the Sea of Rains, and several of our vessels were wrecked along the coast of eastern Hjaírsil. Though we lost many good soldiers and much of our supplies, were were generously taken in by the Exarch of Išaru herself. She is in person as noble and as terrifying as other travelers have said, and I shall not attempt to add to their portraits here. Yet she treated us with utmost courtesy, and addressed us fluently in our native tongue; whatever we desired while we were her guests, she commanded her servants to bring to us instantly, and it was strange to see the people of that land, known abroad for their boisterous and pugnacious natures, to bow and scrape before her, as meek as children.

Our object being lands much further west and south, we took our leave shortly after, generously supplied by the Exarch and furnished with maps and guides to take us as far as Tybran and the isles of Elibom. We turned north-west again after crossing through the Wormsgate, hoping to follow the coast further, and it was in this time, when we put ashore on occasion and had the opportunity to speak with the natives of the region, that we first heard rumor of the place in the desert, of Xil-Artat.

These rumors were greatly confused. Some of our interlocutors said that Xil-Artat was a state of great wealth, as great as Uru (of which, naturally, they had also heard); others said it was but a few huts made of crudely-hewn stones piled up amid the dust; others, that it was in fact below the ground, to shield it from the harsh southern sun; and still others, that anyone who spoke of a city beneath the ground within the bounds of Xil-Artat would be slain instantly, and their body left beyond the city’s walls for the vultures to consume. Each said when they offered their description that it was generally known and all these facts agreed upon, from the salt-marshes to the west to Hjaírsil in the east; and we could not persuade them this was not so, even when we said their countrymen not ten miles behind us had contradicted them completely. Intrigued by these rumors, and determined that if Xil-Artat was the place of wealth some said it was that I should secure some portion of this wealth for the Empire, whether by diplomacy or force, I turned our course decidedly west. We were not to continue south; our Hjaírsilian guides were dismissed. Xil-Artat was now our goal.

Oh! Lord Librarian, my patron and my friend! How I wish I had heeded the misgivings of my comrades when I gave the command. But as to my follies and my regrets, those we shall come to later.

Our first destination was salt-marshes that mark the northern border of the territory Xil-Artat claims for itself. Though the country has but one city, it names for itself in all of its maps an immense hinterland, which the neighboring peoples honor, for that land is almost entirely unpeopled and barren. The arrogance of such a vast territory should by rights be that city’s weakness, and ripe for conquest, but as I soon found, there is little to covet in that wide region. Though the northern coast of the Sea of Elibom is green and fertile, being well-populated but divided into a number of petty princedoms and city-states, one comes after two days’ journey by sail from the northernmost part of that sea to the swamps of Ul-Masim, where a long and nameless river spits out its muddy currents. These swamps are thick with flies and mosquitoes, and we desired to avoid them entirely. However, it was necessary to take on water and food, and we had heard that it was in the center of these swamps, through which a great road had been built, that there stood the market-town named for the swamps, and also known to the people of Xil-Artat as the Swamp Gate, the entrance into their land.

We put our ships ashore at the edge of the swamp, though the men complained bitterly about the heat, the stink, and the flies. I selected a number of companions to venture to the city with me, among them my second-in-command. We ventured north, slowly at first due to the thick mud and treacherous footing, until we discovered a narrow but well-maintained path that had been made of packed dirt upon a slender wall of stacked stones. Such paths, we soon found, crisscrossed the swamp from Ul-Masim itself. We were later told that the inhabitants of the swamp used them to bring their goods to market each month, and this seemed to us an eminently practical scheme, such as one of our own lords or princes might devise to make a marginal country habitable; yet we never saw another traveler on these roads, or indeed any of the inhabitants of the swamps so long as we were there.

After two days’ walking we came to Ul-Masim. It rises suddenly amid the overhanging trees, and its unmortared walls are climbed by flowering vines of every kind, so that the city seems an extension of the swamp itself. Though masked guards stood at every gate to the city, none challenged us as we approached, despite our foreign garb and faces. It was the work of an entire day to find an interpreter through which we could speak to the people, and when we had accomplished the task, we thought that at first we had failed again. For the people of Xil-Artat speak a confused tongue, and whether it is because they are deficient in the powers of the mind or their language has by long isolation twisted itself up in such a way that it inhibits the clear expression of thought, they seem often to contradict themselves, to offer paradoxes as solutions to questions, to suggest wild flights of imagination as solutions to pressing concerns. Within a day it became apparent to me that such a people seemed incapable of the great works of civilization, and I had already begun to form the conjecture that the grand boulevards and halls of Ul-Masim had been built by some previous civilization and that perhaps all of Xil-Artat was but ancient ruins which a tribe out of the north had adopted for their own.

The manner of commerce among the people of Xil-Artat is extremely confused. Though we carried gold and silver, they seemed reluctant to accept them; they did not desire our iron weapons or any other item of our gear, and the glass beads and colorful cloth which we had found so readily in demand to the north were here absolutely worthless. They had goods of their own to offer: swamp fruits, colorful and sweet-smelling, and elaborate masks, and wines and beer and spices which their traders say came from far to the south. They had many goods which they say hailed from Uru, a distant and exotic place; and when I told them that I was myself a Captain of that city’s army, that I had lived there all my life, and that I had never seen these things before, they ignored me, or said that perhaps I had just not been paying attention.

Although angered by this exchange, and the liars who call themselves merchants in Ul-Masim, we nonetheless managed an exchange for necessary goods: we gave them two books, though they could not read them and seem to have no writing of their own, and we gave them also seven good belts and a dull knife. As I am an honest woman, I offered them a sharper implement, but they refused. I do not know what they did with it. They also asked my lieutenant to remain behind for two days and tell them stories of our travels so far, and content that we had the things we needed to proceed further, I left him there with four others of our party, to return to the ships.

When I reached the ships, I found that disaster had struck. Some of the men, displeased as the location of the camp, had taken a ship to go back up along the coast. They had become drunk on the store of wine and plundered a village that owed allegiance to one of the largest states in the region, and I found in my absence that the camp had been attacked by the angry lord of that state. Though his forces had been repelled, all of our ships had been burned, and most of our remaining supplies; and now almost half the expedition was dead. We were too few in number to return to the Empire, and now the region between Ul-Masim and our home was converted into hostile territory, for rumor was spreading across the countryside that the soldiers of Uru were not to be trusted. I spoke to the men and rallied their spirits; yet I acknowledged our difficulty. Yet fear not, I said. We have heard rumor of the city of Xil-Artat; we are even now at the border of its realm. Such people as we have had commerce with in Ul-Masim are strange, but not unfriendly. We will go to Xil-Artat, and thence secure a means of passage home.

So after resting a night we struck camp, finished burying the dead, and returned to Ul-Masim. My lieutenant was in good spirits when I returned, and unharmed, and it seemed that indeed these people were trustworthy. And yet, fearing that they should turn against us in sentiment if the conduct of the mutineers reached their ears, I resolved to go south as soon as possible. For that was, they said, where Xil-Artat lay.

By means of other strange transactions we acquired camels to cross the desert with, and more water. We were told where we might find oases along the road, and wished well, and I set off hoping that the incomprehensible nature of the people of Ul-Masim was like the strange habits and affectations of our own rustic countrymen, and not a general feature of the nation. Surely, my lieutenant agreed, the people of the city itself would be more sophisticated and intelligent, like our own great lords, or the lords of such cities in Sennar as Inisfal and Kurigalzu. Yet I privately I worried that Xil-Artat had never been heard of in those lands, though it lay closer to them than our own City; for I knew that often obscurity is the sign of a dull and uncivilized culture.

The travel through the desert was not eventful. The deserts beyond Ul-Masim stretch on without limit for hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of miles. From the west come great winds that blow up immense amounts of dust and sand, and the roads which the people of Xil-Artat use are therefore built high off the ground, like the aqueducts of Uru that carry water down from the hills. They are ancient, and it is impossible to guess how old. The people of Xil-Artat do not even know, and so I doubt that they built them. They have often collapsed, and often been repaired, and are everywhere made of the pale sandstone which is abundant near the coast and in the desert hills.

At last we came to Xil-Artat proper. That city, made of the sand-colored stone of the hills, rises at once out of the desert when you have crossed the Great Dunes, and from afar it is a jumble of towers and walls and ramparts which cannot be resolved into discrete structures. As you approach, the task becomes no easier, for what is here a courtyard seems to become there a balcony; some streets are cut into the ground, others raised above it; sometimes apartments are on the ground and shops high above in the towers, and sometimes the reverse; and all the city is a maze. And the city has no walls, but rather seems to enfold you as you approach, until you cannot be certain whether you are inside it or outside it.

Is Xil-Artat a wealthy city? Even after years here, I cannot say. They have food enough, and shelter enough, and some of the most ancient parts of the city are carved in an ornate and beautiful fashion. Yet the people of Xil-Artat do not consider themselves wealthy. They show no signs of wealth on their person; they do not treat the objects which lay about them as property of which they must be jealous. Their shops… I have mentioned their shops, but their commerce can hardly be called such. On our third day of Xil-Artat I made a close study of a little stand which seemed to be selling wooden spoons, to learn what the sensibilities of their shopkeepers were, to learn how one should bargain with a seller, to learn what would serve us best as a currency. All day I saw no one purchase; yet the shopkeeper seemed neither agitated nor restless. Some would come and leave handfuls of dust or sand by the door; but they did not speak to the shopkeeper at all. Finally, at the end of the day, when it was time to make his way home to rest, the shopkeeper gathered up some of his wares. He examined the pile of earth by the door, and making a careful count of the goods he carried, he proceeded to walk to the end of a nearby street, which jutted out over the sand beyond the city, and flung everything he carried into the desert. He went home without locking the door. Such is but one example of the insanity of the people of Xil-Artat.

Here as in Ul-Masim we struggled to make ourselves understood; my lieutenant, who had been diligently studying the tongue of Xil-Artat in an effort to make communication easier, seemed to make headway only slowly, but he learned that there was someone in the city who was considered its lord after a fashion, and I was determined to make myself known to this person, to open relations between our two nations. In any sensible city I am certain we would have been brought before its lord as soon as we arrived, for we were strange in dress and speech and appearance, and even in those backwards places that do not know of our Empire, its wealth and power is apparent in the meanest of its representatives. I had hoped, therefore, that the Lord of Xil-Artat would be eager to open dialogue between our two states, that indeed he would see there was nothing for a backward nation as his own to do when confronted by a superior people except to ally himself as closely as possible with them, and I was perplexed that, insofar as there was any power which ruled this city, it had not made itself known.

We took a manor on the outskirts of the city for our own use; none of the natives of Xil-Artat seemed to object. Sometimes we found strangers in its halls, but though we ordered them to depart, even threatened them, they seemed to pay us no attention. From here I sent some of the men out to search the city for intelligence; the lieutenant I told to learn as much as he could about the people and their customs, and I sought the Lord.

What follows are some observations on the habit and customs of Xil-Artat.

Most of the people wear long robes of thin fabric, whose cloth is lightly colored, to protect themselves from the harsh sun. Their garments are richly embroidered, with ornate geometric patterns, and sometimes what seem to be the suggestion of people, or animals, or parts of the body. Yet they shun obvious iconography in most instances, especially of faces. And to this end, perhaps, they also commonly wear masks. All are well-decorated, but all are equally impassive; and they speak with a flat affect, so that they seem to be a people without emotion.

I do not know what the religion of Xil-Artat is. They have no priests and no shrines, and seemingly no temples. Yet there are customs which they observe with religious fervor. All houses have their doors in the west; all shops have their doors in the east. Great markets are held on regular intervals, even if they fall on holy days in which commerce is forbidden; on such occasions the people still bring their goods to market, but they buy nothing. They will haggle over prices, but then walk away. And everything is carried home again by its original owners at the end of the day. Another custom, which I can only surmise has some religious feeling behind it, concerns the face: even when the face is depicted, it is shown without eyes. The people of Xil-Artat have a terrible fear of eyes, and we soon learned they were far more comfortable in our presence when we took to wearing masks after their custom.

And yet despite the apparent chaos of their society, they do have their laws. When an offense against the peace, or against another person, or against the desert, or against the soul of a building, is committed, a court is convened on the spot, with three citizens as judges; and the nearby people crowd together, and half of them act as the lawyer for the prosecution, and half of them act as the lawyer for the defense; and they all shout, like a rioting mob, their arguments and their comments and their observations, and sometimes even irrelevancies and obscene jokes; and out of this confused mass of shouting the judges choose for themselves what to believe, according to their own conscience, and pass sentence immediately. Where the perpetrator is not known, the sentence is passed upon a stone, and it is hurled to the ground and dashed to pieces. Where the perpetrator is human, they are dragged to the nearest ledge and thrown off--whether it is only two feet above the ground, with soft sand below, or from the top of a high tower onto solid flagstones. These verdicts are thought of as fair and just by everyone involved.

The people of Xil-Artat speak often of poetry and of philosophy. They love philosophical speculation, and this, too, verges on religious custom. For they treat abstract thought and experiments of the mind with great gravity, and if you can convince a man of Xil-Artat of a new belief, he will incorporate it into every aspect of his life immediately and without question. They constantly formulate new heresies of metaphysics among themselves, and their beliefs often change, but they change not in the manner of a child whose imagination has departed suddenly in a new direction, but with utmost gravity and seriousness. Some people in Xil-Artat believe that no one exists without their mask. Some believe that Xil-Artat is a hallucination of the men of Uru that did not exist before we entered it. Some believe that darkness is a physical substance, and that night is not caused by the setting sun, but by a fluid that rises from the desert, and is gradually dissipated by the wind. Some believe that the souls of the dead are reborn as new beings, according to the merit of their previous existence; and that to be born human is the most wretched fate reserved for only the most awful of creatures. Some believe that on the occasion of sleep, a doppelganger roams the city, whose deeds are their dreams; and still others believe that these doppelgangers sleep, too, and produce doubles of their own. One man whispered to me gravely that there was a second city below the ground, and that was where the doubles of the waking waited, but that they would not wait forever, and one day that city would return. I asked him to explain what he meant by “return,” but he would not. And he said the city had a name, but to utter it was a crime. As we were then standing near a high ledge overlooking the marketplace below, I did not press him on the subject.

Xil-Artat’s wealth, such as it has, is scattered about the city. Weapons hang in many halls, and tables are sometimes adorned with goblets and platters of precious metal. Pantries are here full of food, and there nearly empty; and when someone is hungry, or desires to drink, or wants any material thing, they go to wherever is most convenient, and have use of what is there. But they are as likely to select bowls of plain wood as goblets of fine gold, and as likely to make a meal out of whatever can be found in a meagerly-supplied kitchen as to prepare a feast in a well-supplied one; though in the former case they will still complain of hunger. Likewise, their daily occupations seem to be at random. Sometimes they will rise and go to the irrigated terraces to the west of the city and spend their day pulling weeds in the hot sun, and sometimes they will walk to the nearest market-stall and sit, as though they are the proprietor, and sell whatever they find inside. No one compels them to do any task, nor do they themselves seem to prefer any labor, however ill-suited they are for it.

After three weeks, my Lieutenant’s skill with the language had rapidly increased; yet I began to fear for him, for it seemed as he learned the tongue of Xil-Artat he forgot his own. He began to speak in the looping, riddling fashion of the foreigners; he found it harder and harder to answer directly questions put to him, and when I ordered him to take a period of rest, thinking he had taken ill with the desert heat, I found him later in the shade writing the same phrase in the dust, in the tongue of Xil-Artat but in the letters of our own language, over and over again. Each time he would write it out he would erase it and begin again. I stamped it out with my foot, and told the men to lock him in his room for the evening. I came back later to find that there was also a crude drawing he had made next to where the words were written. It was difficult to discern the intent of the image, but it seemed to be several figures, dressed in the manner of the people of Xil-Artat, all without eyes.

When it had been six weeks since our arrival, I secured an audience with the Lord of Xil-Artat, whose title, I had learned, was the Master of New Truths, or the Chief Heretic. This Lord received me at about two in the morning, in a small house in the southern quarter of the city; the moonlight shone in through a stone grillwork on the far wall, and he was alone, though dressed finely and seated on an ornate rug. I came with a scribe, to take notes, and one of our interpreters. I named myself and my errand, and described Uru, and our Empire; the Lord of Xil-Artat was polite, but remained impassive. He asked why I had sought so strenuously to speak with him, and I said, to open relations between our two states. Had I not already done so? he said, for I had traded extensively with the people of the city, and in Ul-Masim. Indeed, I said; but there could be better cooperation between us, and more profit to be had for both ourselves and for him. This he did not seem to understand, and he spoke instead of what he was thinking about having for breakfast. I steered the conversation again to his city, and said that while the customs of his people were strange to me, I was certain friendship could exist between his people and mine. This he enthusiastically agreed with, and we spoke a little about the customs of my country, which baffled him as much as his customs did me. This put him at great ease, and I apprehended that, though the Lord of this city, he was uncomfortable around strangers. I spoke about my other adventures and explorations in the service of the army, and these tales he also enjoyed; he had heard neither of Inisfal, or of Tybran, or of Hjaírsil; nor even the names of his closest neighbors to the north. All the world outside Xil-Artat seemed to be new to him. I had thought that we had begun to establish a rapport, when he suddenly remarked that this was the strangest dream he had ever had, and he wondered if any of it was true. I insisted that this was not a dream; that he was as awake as I, and that all of what we had spoken about was true. He said that I seemed extremely confident, given that I could not be sure he existed, nor the reverse; and I became angered by his solipsism. I berated him for the weak-mindedness of his people; for the disorder of their customs and law; for the time they wasted on meaningless ideas and fearful rumors. I spoke of the man who thought there was a second city beneath this one, and how in my homeland, madmen are locked up, or treated by doctors, not allowed to roam free in the streets.

Oh, said the Lord of Xil-Artat, Mlejnas is quite real, I assure you. Mlejnas, he said, was the name of that city, and he said that everything they said about it was true; even false things. I was at this point prepared to leave and not return; for it was evident he was as mad as all the rest. Very well, he said; but if you want to look for Mlejnas, it is all around you; yet those who seek Mlejnas never return.

I was at this point ready to depart for good. Our mission seemed a failure, and the most logical course of action, I believed, was to depart Xil-Artat for Elibom, to the southeast, where I knew there were some small towns and, at the end of the peninsula, a Tybranese trading-fort. From there, a small contingent might make passage to Sennar or to Hjaírsil, and get a message back home. It would take some months, possibly more than a year, but ships could return for the rest of the expedition. As a leader, it was properly speaking my obligation to make this happen, and yet a second duty held me back: my duty to my friend.

My lieutenant at this point had taken to writing on the walls of his room, and refused to leave even when the door was left open. He would eat only rarely, and at night he screamed deliriously, in a mixture of our language and Xil-Artat’s. He was now fluent in the latter, despite rarely leaving the manor, and I wondered if the strange visitors we received in the night were conversing with him; though I had given orders that any outsiders found in the manor should be physically ejected at once, especially if they were in the hallway outside the lieutenant’s room, perhaps some still escaped the watch of the guards and filled his mind with their obsessive delusions. I had tried to speak with the lieutenant as a friend; to draw out his obsessions, to understand the working of his fevered imagination, but it was impossible to follow his thoughts, especially when he lapsed into that other language, of which I still knew little. Yet after I spoke with the Lord of the city, I realized there was a familiar word, repeated in my friend’s ravings. Not often, but from time to time, he said the word Mlejnas. Though I hoped to bring my comrades home as soon as possible, I knew that if a solution to my friend’s sickness was to be found, it would be found in Xil-Artat.

To the former end, I appointed the under-lieutenant temporary commander of the expedition. She received her orders, and would lead the expedition east, to Elibom. They would make their way slowly, so as to conserve supplies, since the nearest towns to Xil-Artat were more than a week’s journey from the edge of the desert. The Tybranese were notorious pirates, I reminded her, but our nations had a treaty, and they ought to honor it. I would remain behind with the lieutenant; two others of our number, who were also his beloved companions, elected to remain with me as well. The under-lieutenant departed three days later, after all preparations had been made; on the morning of departure, I gave her a field promotion to Captain as befit her new responsibilities. I hope that that promotion has been honored since her return. I did not hear from the expedition after they departed, but that did not distress me, since I knew they had no means of getting a message back to Xil-Artat, which receives precious little news of the world outside.

I had now formed a number of theories concerning the history of this place. First, the people of Xil-Artat were not the builders of Xil-Artat. Perhaps they had found its ruins; perhaps they had conquered it. Either way, they lived in terror of those who had built it, the reasonable, rational civilization that had been capable of creating roads through the desert, of ferrying stone from the eastern hills, of tapping wells into the rock below the city; for a superstitious people will always live in fear of a rational and powerful people, and thus the ruins of past greatness will instill in them a terror. But something had gone terribly wrong in the minds of the people of Xil-Artat, and now this terror had become a madness, infecting every aspect of their customs, habits, and society. A strong-minded people of good sense, as our ancestors had been, would have been immune even had they clung to superstitious ideas, but the harsh conditions in which they lived and perhaps the dry air had sapped their strength of mind. Their city was obviously in steep decline, and would be utterly deserted within perhaps two generations. From this it followed they were a young people; they could not have endured in this state for long, and could not have lived in this place more than fifty or a hundred years. Perhaps, I supposed, our historians could one day examine their legends and their history to determine their real origin; but such things were not immediately my concern.

I had also decided that this “Mlejnas” represented some knowledge I could use to help my friend. A city below the ground was preposterous, of course; but perhaps there were indeed ancient ruins underneath us, and that in these ruins, somehow, some knowledge of the past was preserved. There were, after all, many things the people of Xil-Artat had words for in their tongue that they did not possess--they had a name for libraries, but no books; they had a name for doctors and medicine, but no healing arts of their own; they could speak coherently (on occasion) about philosophy and matters of natural science, though they had no universities, no schools, no systematic studies of the spirit or mind or natural world, and so forth. I knew that there were things in the world inexplicable to our own science, but that such things are merely rational questions awaiting systematic study. And perhaps a clear-minded approach to the question of the history and builders of this city could offer my friend some comfort, so that the madness of its people would cease to torment him.

Commending him to his friends’ care, I began to search the city day after day, night after night. By my increasingly insistent questions on the subject of Mlejnas, I drove people away from me; merely mentioning the name caused them to sprint off without a word, as though they had just remembered leaving a loaf of bread in the oven that morning. When no one would speak to me at all any longer, I simply began to search every house, every tower, every courtyard, for anything that might give me a useful clue. I no longer went about dressed in the Xil-Artat manner; I scorned their garish masks and their elaborate robes. I would no longer indulge them in their wild imaginings.

My search of various buildings took me deeper and deeper underground. Xil-Artat, I discovered to my gratification, was indeed built on a layer of ruins. These ruins were more ordered, more logical than the city above, their upper levels that now were cellars and basements being laid out like orderly streets and rows of houses. There seemed to be ruins further down; half-buried decorations in the walls, or steps whose passage was now filled with rubble or sand attested to even older layers of the city below. It was easy to imagine what a superstitious mind could come up with in such dark spaces. But I could find no passageways further down which were open, and though in some places the buried ruins seemed as ancient as the ruins of Uru’s acropolis, or even older, nothing yet offered me information as to their origin.

So long as my friend’s suffering grew, however, my energy increased. And after a few weeks, I made a discovery. There was, not far from the central marketplace, a certain house whose roof had collapsed and which was now filled with dust, that had a cellar larger than the rooms above. In the corner of that cellar was an iron trapdoor, very old and worn, and rusted entirely shut. Not the strength and that of my two sane companions working together could open it, and the stone floor was entirely solid; we could not dig around it. I conducted a thorough search of the surrounding houses and towers until I found a large hammer, like a blacksmith’s, and a length of iron to serve as a crowbar. For four days I labored to break the fastenings that held the door in place and pry it out of its setting. It had been made to exacting quality, as good as the work of any metalwright in the world now living, but it was ancient, and eventually, it yielded. When I had sufficiently loosened it in its bed, I was able, with some great difficulty, to wedge the crowbar beneath its edge and to lift it aside. It fell back to the stone with an earsplitting noise, but revealed below a dark passage, with a musty odor.

I returned the next day with a number of torches, and entered the passage. At once, I felt my theories were confirmed. These ruins were nothing like those above. Even at their most well-organized and attractive, they had had something of Xil-Artat’s madness to them, something of its geometric patterns and labyrinthine shapes. They had been mostly plain stone. These rooms were entirely the opposite.

By their size and the windows that now only spilled sand and rubble into them, they had once been the upper gallery of some light and airy palace. The torchlight reflected sweeping, curling shapes off the walls, in which animals and children and people danced and played, all looking out at the viewer and smiling. I could not help but feel that if these rooms below were exchanged for those above, Xil-Artat would be a magnificent city indeed, the deep red pigments and gold left contrasting beautifully against the bare sand, the blue desert sky shining in through the windows. Alas for the fallen cities of history! I thought.

It is a curious feature of being out of sight of the sun that time is difficult to perceive. This had happened to me only once before, in the caves above Brighthaven, and there the effect was only that of spending an hour or so underground, and emerging to discover the sun had already set. Then I had been at leisure, admiring the natural beauty of the caverns, and so had not had occasion to spend longer than I wanted underground. Now, I had a duty to the lieutenant; and soon, I realized I had been wandering the passage for a long time. How long had it been? I had exhausted three torches already; but they were slow-burning things, their light dimmer as a consequence, and I could not say how long each had lasted. Nonetheless, this was my first breakthrough in weeks, and I had plenty of light left, so I continued on.

This gallery led me deeper, to more rooms, each more ornate than the last. Some had accents of lapis lazuli; some still had ancient furniture, carved out of black wood; the dry air had preserved them, even as their cushions had crumbled to dust. As I moved from room to room, I found myself going from a younger part of the building to an older; and to my surprise, the stairs led continually down. And it was a curious feature: the animals and children and adults on the walls, I noticed, detailed in every respect and in nearly every respect exquisitely proportioned, had eyes much larger than I expected. And each figure gave the impression that it was watching me.

At length, the rooms and hallways came to a great pair of doors. I surmised this had once been the grand entrance of the palace; if they could be moved, there would be nothing but sand beyond. I gave one a half-hearted tug. To my astonishment, it glided silently open, light on its hinges despite its size, showing a cavernous space beyond.

Here, there was an immense darkness below; but vaulted paths crossed this darkness, meeting in the middle of this huge space, leading to more sets of doors set in various points of the far walls. But the space was not dark in its upper reaches, not entirely. A dim light glowed from sources I could not see that illuminates the walls partly, and every free space of these walls was covered in ghastly faces, faces with tortured expressions, faces which seemed to silently curse the empty air. Each face was different. Each had ugly, bulging eyes. Yet I felt as soon as the door was opened that each eye, directly or askance, fixed its resolute attention only on me. For the first time, I was not entirely at ease.

The paths which bridged the great room had no railings; I crossed them warily, wondering what sort of people would build an awful place like this. When I reached the platform in the middle I looked back the way I had come, then around again. I noticed one of the far doors was open, and, what was more, something seemed to be standing just beyond it, a figure like a man. I called out to them, but there was no movement and no response. I walked toward it, and again I called out, and again, it remained impassive. Yet as I approached I could see it a little more clearly, dim as the light was, and it did seem to be a man, dressed not unlike a man of Xil-Artat. It bore an ornate mask, with a howling grimace rather than a quiet face, and its robes were the color of blood. And when I had nearly reached the door, it turned and fled.

Angered that this stranger had fled from me, I ran after in pursuit; this door led not to another great cavern, but to a hallway, whose walls were likewise covered in awful faces, and I ran down this hall, following the figure disappearing behind the corner ahead of me. This hallway twisted like a maze, and soon I found myself lost, the stranger nowhere to be seen. I cursed myself for my foolishness in recklessly following, and now and again I would hear the sound of footfalls that seemed to be approaching swiftly, but when I tried to find their source, they always rapidly faded.

This place, whatever it was, was no city. Was it Mlejnas? What was Mlejnas, if not a city? If not Xil-Artat, as it had been known in times past? Who were these wanderers in abandoned hallways beneath the ground? Such questions I asked myself in that moment, foolish though they were. I gathered my wits and continued my exploration. I tried to find my way back to the great chamber, thinking the others paths that led from it might be more helpful than this, but I only found more of the same maze, its walls seeming now to be higher and higher, and coming closer together, as though the earth was closing itself up on either side.

Yet this oppression was not absolute; here and there there was a door. These led to small rooms: some bare closets of stone, some with objects scattered about their floor. One held bookshelves; I opened one to find strange letters, close together, covering every inch of every page. Another was written in my native tongue, but though I recognized the words, they made no sense together; it was an endless stream of nonsense. Another was written with familiar letters, but in no language I recognized. I quickly left that room behind.

The room after that had a man in it. He was not masked; he sat, wearing only loose-fitting trousers, cross-legged on a cushion facing the wall, and he was in every respect from my vantage point a double of my friend, the lieutenant. I cried out when I saw him, in confusion as much from surprise, and the voice that answered me was indeed the lieutenant’s, calm and devoid of the madness that had plagued him since coming to Xil-Artat. He greeted me by name and bid me come in. I walked up to him and put out a hand to lay it on his shoulder, to turn him to face me.

“Don’t,” he said to me. “Do you not know me?” I asked. “I am Shurnamma; look at me, my friend.” “Stop,” was all he said in reply; so I withdrew my hand, and took a step back. “Will you not speak to me? Why are you here? ” I asked. “I shall answer any question you put to me, Shurnamma; but consider carefully which questions you want answers to.”

“What is this place?” I asked. “It is Mlejnas,” he said. “What is Mlejnas?” I asked. “It is the answer to Xil-Artat.” This response irritated me; and sensing this, the lieutenant said, “Do you know what Xil-Artat means? The name is not arbitrary: it is ‘the noiseless land,’ in their tongue.” “And so silence demands an answer?” “Or perhaps silence is an answer to something else,” he replied.

“You know that I dislike games,” I said. “I have a practical view of the world, and hate superstitious talk. The madness of Xil-Artat tries my patience, and in your infirmity I have granted that you have been unable to discern the difference between what is real and true and what is false; but now you are better, and we will go back up together, and put all this behind us. We will return home, and forget everything about Xil-Artat.”

“I cannot leave Xil-Artat,” the lieutenant said. “And why not?” I asked. “Because I cannot leave Mlejnas,” he answered. “What!” I cried. “Is Xil-Artat now Mlejnas?” “Not now,” the lieutenant said. “But one day.”

“Clearly you are still afflicted, if you think the dusty ruins of one city can rise up to replace another!” I said. “Where do you believe we are standing?” the lieutenant asked. “These are the ruins on which Xil-Artat was built,” I replied. “It is the ruins left behind by some greater people. A primitive imagination has made it into a thing of terror to the inhabitants of Xil-Artat; but there is nothing here.”

“You have not seen with your eyes,” the lieutenant said slowly. “You stand now in Mlejnas, built by the people of Mlejnas; the people of Xil-Artat built Xil-Artat. Xil-Artat was built when Mlejnas was built. Xil-Artat caused Mlejnas to be, and Mlejnas caused Xil-Artat. Neither has its beginning without the other. Each is the answer to the other. When your city was but a village on a stony hill, Xil-Artat and Mlejnas were. When your people were wandering the world, seeking a home, they were ancient. Maybe even before everything, before the Deluge, before the world was remade, here they were. Here they have survived. Here they will survive everything. Xil-Artat lives, because Mlejnas lives. Xil-Artat wakes while Mlejnas sleeps. And maybe Mlejnas will not sleep forever.”

“And what will become of Xil-Artat and her people then?” I asked scornfully.

“Then they will be Mlejnas,” the lieutenant said. “Then they will have always been Mlejnas. The ones who fled below the earth to escape the end, the ones who have survived since before your country existed, the ones who scored out flesh with knives and stuffed our mouths with dust; who cut us out of ourselves and threw us away, the ones who wait, the ones who suffer in the dark, will be the ones above. As they once were, maybe. As, perhaps, they have always been.”

“You speak of fleeing, of suffering, of catastrophe. Then Mlejnas was indeed destroyed? Or Xil-Artat? Or both?”

“Mlejnas was a way to survive destruction. Xil-Artat is what was left. Or was it the other way around? We have trouble remembering. It does not matter. This was their lesson: that you can survive anything, if you can put the pain somewhere else.”

“You speak nonsense, my friend. This is all nonsense.”

“Shurnamma, you want an answer that pleases you. That lets you put these things into an order you can understand, the same order which you impose on the rest of the world. Such an answer does not exist. There is no order, no history for you to discover here. How else could Xil-Artat be?”

I advanced again, intent on taking the lieutenant back to the surface with me. I laid my hand again on his shoulder, and the moment I did, a terrific fear seized me. Perhaps it was his strange discourse; perhaps it was my own rational mind finally being affected by the madness of those around me; but I became convinced that I should not behold his face, that to do so would, in that instant, be an awful mistake, and that I did not want the thing I was now touching, which was not the lieutenant, and which was not my friend, to follow me out of that room. I withdrew, and wordlessly closed the door behind me.

I continued through the maze, attempting to ignore the thoughts pressing in on my mind from all sides; I tried to keep the image of the sunny city above me in my mind, though now I did not know if the sun had long set or not. The torch in my hand was burning still, though in my anxious state I could not have said if it was my fifth or my fiftieth, nor how many I had originally brought. Eventually, the maze gave way, and I found myself in another set of rooms, that seemed to be fashioned as shrines. Each bore the figure of some grim god, and each was in its own way more violent and obscene than the last; I hastened through these rooms, ignoring the faces peering at me from every wall, and doing as best as I could to observe that now their eyes followed me as I walked, shining with either what was varnish or tears.

At last I came to a hall, and amid this hall flanked by pillars was a throne. The masked figure in red robes sat on this throne, and it was red and gold; and the pillars were red, and all the walls, and tapestries of rich reds and gold, embroidered with thousand and thousands of white eyes hung between the pillars and above us. From a distance I seemed to recognize the man in the mask. Here he sat enthroned like a lord, while above he had seemed content with simplicity; he looked for all the world like the heresiarch of Xil-Artat. But where the one had seemed sleepy and indolent, incurious about what was before him, this one sat alert, watched me approach, turned his head this way and that, as if to examine me, with swift and inhuman motions, and when he stood, like an insect approximating the manners of a man, it seemed that either he carried himself in the strangest fashion imaginable, or that his proportions were entirely wrong.

“Are you the lord of Mlejnas?” I demanded of him. He did not move or speak.

“Speak!” I cried.

“I want a true answer; a clear answer,” I said to him.

“An answer to Xil-Artat?” he asked; and his voice was indeed the voice of the heresiarch.

“To Xil-Artat, to Mlejnas, to everything.”

He laughed; and when he laughed I heard other voices, too, and felt presences around me, just out of vision; but I fixed my gaze ahead, for in truth, I was far too afraid to look into the shadows.

“One answer, one answer, how can you insist on one answer? How can you insist on one answer when some questions have thousands?”

“I want the truth. One truth. The real history of this place. There is only one history of Xil-Artat.”

“It may be the custom of your country that there is one history, and one only. It is not so in Mlejnas. It is not so in Xil-Artat. There are a thousand histories of each, and all of them are true, and who is to say how many you have endured already, Captain Tirigan?

“Here is one answer: when the world was destroyed, the people of Xil-Artat hid part of themselves below the earth to survive. But not forever; they fear the day it shall return. And they are right to fear it, for that hunger and that suffering has grown, and when it returns it shall devour them all. It shall devour the world.

“Here is another: in the tongue of Xil, the opposite of ‘noiseless’ is not ‘noise.’ The opposite word means ‘screaming.’”

And as I watched, transfixed by the thoughts which contended about this strange city to which I had come, the King of Mlejnas took off his mask; and his face was the face of the Heresiarch, the Lord of Xil-Artat; except that he had no eyes. No eyes at all; not even the sockets where eyes should appear. And he opened his mouth wide, stretched it wider and wider, as if he sought to swallow everything around us, and he began to scream, to scream and scream, a loud and hideous sound, and the things that stood just out of view, that filled the room behind me and beside me, they screamed too, a terrible noise of unspeakable pain and loss and rage; and though I covered my ears and I fled as fast as my feet could carry me, in any direction I could go, the screaming became only louder, ever louder and unceasing.

I remember little of what transpired after that. I fled through the bloody halls of Mlejnas, the screaming halls of Mlejnas, the halls of eyes that watch unceasing. I fled, but I never escaped them. Even when I awoke later, in a square in Xil-Artat, surrounded by masked figures peering over me with concern, I was still in Mlejnas, and I shuddered and wept, fearing what I would see if I reached out and lifted the masks of their faces. Oh, Izaru, my friend, when the people of Xil-Artat tell you that no one who seeks Mlejnas ever returns, they don’t mean you die. It’s much worse than that, I am afraid. For Mlejnas is all around me now. I will never be without it. For now, though, at least part of me inhabits Xil-Artat. I long to see my home, but I cannot leave! For only here there are no eyes. Only here they are not watching me. But it won’t last forever. I know it’s there now. I know that one day it will wake. And when Mlejnas takes the place of Xil-Artat, we shall all have our answers: all that we have forsaken we shall have to answer for, and all our tears and prayers will not suffice.

When I returned to the manor the lieutenant was gone. He had, my companions said, fled into the desert shortly before my return, with nothing but the clothes he wore, and surely would soon die of thirst or exposure. Yet I cannot help but think his body will not be found in the desert. I sent my companions away after that; they opted to take the road north to Ul-Masim, rather than try to reach Elibom; and the last news I heard of them was that they had departed Ul-Masim, heading east along the road that leads to Išaru.

The screaming, yes. I hear it when I wake. I hear it in my sleep. I hear it when I close my eyes and remember those writhing, tortured faces. I hear it now, now as I sit in the sunny courtyards of the northern quarter, as I admire the blue sky, as I drink clear water from a silver cup, as I watch the people go too and fro. It is a quiet day for them. Theirs, yes, theirs. Theirs is the noiseless city above. Mine--ours--is the cold screaming beneath the ground.

(signed)

Captain Shurnamma Tirigan

Catalogue item I.G.-uM.1733. A later hand has added to the last page of the missive: “Tirigan’s Expedition, launched 1669 AUC, vanished southeast of Inisfal in 1672, and, so far as reports sent back from 1669-1671 indicated, never lost ships off the coast of Hjaírsil, was never furnished with aid by the Exarch of that country, and never diverted from its intended course, south from the Wormsgate. The preceding document was given to an Urusc courier in the city of Ul-Masim in 1733, by an unknown party. Though apparently in the Captain’s hand, and apparently corroborating some of the tales of later expeditions to Xil-Artat, it is the judgement of the archival staff that this document is a forgery, or perhaps the work of a lunatic; and that everything it contains is nothing but the most unusual of lies.”

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

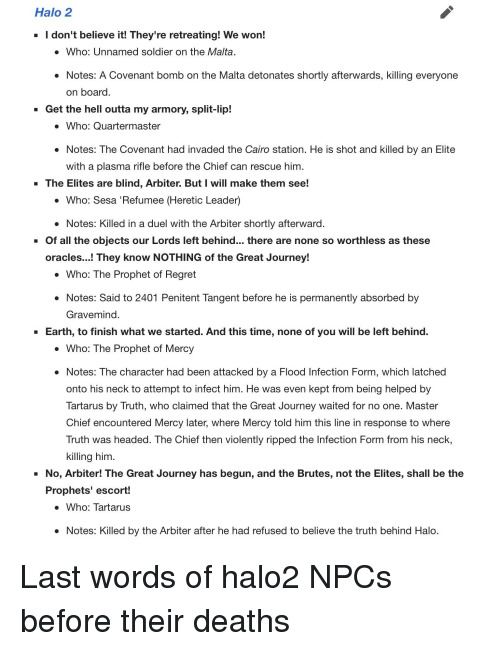

Halo, Journey, and Regret: Halo 2 I don't believe it! They're retreating! We won! . Who: Unnamed soldier on the Malta * Notes: A Covenant bomb on the Malta detonates shortly afterwards, killing everyone on board Get the hell outta my armory, split-lip! . Who: Quartermaster * Notes: The Covenant had invaded the Cairo station. He is shot and killed by an Elite with a plasma rifle before the Chief can rescue him The Elites are blind, Arbiter. But I will make them see! . Who: Sesa 'Refumee (Heretic Leader) . Notes: Killed in a duel with the Arbiter shortly afterward Of all the objects our Lords left behind... there are none so worthless as these oracles...! They know NOTHING of the Great Journey! . Who: The Prophet of Regret * Notes: Said to 2401 Penitent Tangent before he is permanently absorbed by Gravemind Earth, to finish what we started. And this time, none of you will be left behind. . Who: The Prophet of Mercy * Notes: The character had been attacked by a Flood Infection Form, which latched onto his neck to attempt to infect him. He was even kept from being helped by Tartarus by Truth, who claimed that the Great Journey waited for no one. Master Chief encountered Mercy later, where Mercy told him this line in response to where Truth was headed. The Chief then violently ripped the Infection Form from his neck killing hinm No, Arbiter! The Great Journey has begun, and the Brutes, not the Elites, shall be the Prophets' escort! . Who: Tartarus * Notes: Killed by the Arbiter after he had refused to believe the truth behind Halo

0 notes