#Montmédy

Text

La Gaume et la Meuse, balade entre la Belgique et la France.

2024, encore une année qui s’annonce riche en voyages (non, pas de spoiler, sinon ça tue tout le suspense 🤐)! En guise de petite mise en bouche, j’ai décidé d’aller me balader “à domicile”, en restant dans ma petite Belgique, en jouant toutefois les funambules avec quelques incursions en France toute proche… Côté météo, comme tu t’en apercevras, j’ai pas sorti le tiercé gagnant: week-end gris et…

View On WordPress

#Avioth#Belgique#bière#citadelle#France#Gaume#Louppy-sur-Loison#Marville#Meuse#Montmédy#Montquintin#Orval#Stenay#Torgny#Virton#zigomar

1 note

·

View note

Text

If the revolutionaries are bothering you you can use your connections to escape in disguise from Paris and flee to Montmédy where royalist troops are massing

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The King and all his family left Paris, fortunately (without problems), on the 20th at midnight. I led them to the first post. God grant the rest of their journey will be just as happy. I am waiting here for Monsieur at the moment. I will then continue my journey along the border, to join the King at Montmédy, if he is lucky enough to get there.

--Axel von Fersen in a letter to his father, June 22, 1791. Written in Mons, where Fersen (for unknown reasons) met up with the comte de Provence (who had no reason to be there) and others, including de Provence’s mistress (who just happened to leave Brussels for Mons at the same time so as to meet Provence).

#french history#french revolution#18th century#gotta love fersen's confidence!#in case you can't tell I'm salt-deep into the Fersen/Provence collusion theory at the moment

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jules Bastien-Lepage - Self portrait - 1880

oil on canvas, height: 31 cm (12.2 in) Edit this at Wikidata; width: 25 cm (9.8 in)

Panier (0)Musée Jules Bastien-Lepage et de la Fortification, Montmédy

Montmédy (German: Mittelberg) is a commune in the Meuse department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

Jules Bastien-Lepage (1 November 1848 – 10 December 1884) was a French painter closely associated with the beginning of naturalism, an artistic style that emerged from the later phase of the Realist movement.

His most famous work is his landscape-style portrait of Joan of Arc which currently resides at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City.

Bastien-Lepage was born in the village of Damvillers, Meuse, and spent his childhood there. Bastien's father grew grapes in a vineyard to support the family. His grandfather also lived in the village; his garden had fruit trees of apple, pear, and peach up against the high walls. Bastien took an early liking to drawing, and his parents fostered his creativity by buying prints of paintings for him to copy.

Jules Bastien-Lepage's first teacher was his father, himself an artist. His first formal training was at Verdun. Prompted by a love of art, he went to Paris in 1867, where he was admitted to the École des Beaux-arts, working under Cabanel. He was awarded first place for drawing, but spent most of his time working alone, only occasionally appearing in class. Nevertheless, he completed three years at the école. In a letter to his parents, he complained that the life model was a man in the pose of a mediaeval lutanist. During the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, Bastien fought and was wounded. After the war, he returned home to paint the villagers and recover from his wound. In 1873 he painted his grandfather in the garden, a work that would bring the artist his first success at the Paris Salon.

After exhibiting works in the Salons of 1870 and 1872, which attracted no attention, in 1874 his Portrait of my Grandfather garnered critical acclaim and received a third-class medal. He also showed Song of Spring, an academically oriented study of rural life, representing a peasant girl sitting on a knoll above a village, surrounded by wood nymphs.

His initial success was confirmed in 1875 by the First Communion, a picture of a little girl minutely worked up in manner that was compared to Hans Holbein, and a Portrait of M. Hayern. In 1875, he took second place in the competition for the Prix de Rome with his Angels appearing to the Shepherds, exhibited again at the Exposition Universelle in 1878. His next attempt to win the Prix de Rome in 1876 with Priam at the Feet of Achilles was again unsuccessful (it is in the Lille gallery), and the painter determined to return to country life. To the Salon of 1877 he sent a full-length Portrait of Lady L. and My Parents; and in 1878 a Portrait of M. Theuriet and Haymaking (Les Foins). The last picture, now in the Musée d'Orsay, was widely praised by critics and the public alike. It secured his status as one of the first painters in the Naturalist school.

After the success of Haymaking, Bastien-Lepage was recognized in France as the leader of the emerging Naturalist school. By 1883, a critic could proclaim that "The whole world paints so much today like M. Bastien-Lepage that M. Bastien-Lepage seems to paint like the whole world." This fame brought him prominent commissions.

His Portrait of Mlle Sarah Bernhardt (1879), painted in a light key, won him the cross of the Legion of Honour. In 1879 he was commissioned to paint the Prince of Wales. In 1880 he exhibited a small portrait of M. Andrieux and Joan of Arc listening to the Voices (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art); and in the same year, at the Royal Academy, the little portrait of the Prince of Wales. In 1881 he painted The Beggar and the Portrait of Albert Wolf; in 1882 Le Père Jacques; in 1885 Love in a Village, in which we find some trace of Gustave Courbet's influence. His last dated work is The Forge (1884).

Between 1880 and 1883 he traveled in Italy. The artist, long ailing, had tried in vain to re-establish his health in Algiers. He died in Paris in 1884, when planning a new series of rural subjects.

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

(...) Ich glaube überhaupt, daß ein Teil der Leute zu Haus vollkommen den Maßstab verloren hat. Daß bei einem solchen Kampf Hunderte sterben und Tausende verwundet werden, bedenkt so jemand nicht. Aber `in Berlin wird man allmählich etwas ungeduldig. Denn es ist schwer – Butter zu bekommen. Ich unterschätze ja die Schwierigkeiten zu Hause nicht. (...) Aber schließlich, hier sterben die Leute und und in Berlin ist es nur teuer... Das ist das Volk, für das unsere Besten sterben sollen. Das ist ´das Vaterland`...

5. April 1916, Ludolf Krehl aus Montmédy/Lothringen an seine Frau.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dieu ne ment pas !

https://youtu.be/guPkbAjRFHE

Lorsque j’avais l’âge de 6 ans, je passais mes vacances chez mon oncle à Montmédy dans le département de la Meuse en France. Il était le chef de Gare.

Sa maison était située en face d'un marchand de chevaux, M. Lévi, et je passais mes journées à regarder ses magnifiques chevaux.

Un jour, mon oncle me dit qu'il allait m'acheter un cheval. Je le crus sur parole et tous les soirs, je m'endormais en pensant au magnifique cheval que j'allais avoir.

Vers la fin de mon séjour, il me demanda de l'accompagner pour l'acheter.

Il alla discuter dans le bureau du marchand et sortit en disant… Ça y est. Tu vas avoir ton cheval !

Je l'embrassais de tout mon cœur, reconnaissant combien cet oncle était bon pour moi ! Je ne tenais plus en place disant à toutes les personnes que je rencontrais : Mon oncle m'a acheté un cheval !

Hélas, mon oncle m'avait menti. Je n'ai jamais eu de cheval !

Plus tard, je m'aperçus que mon oncle avait un penchant assez marqué pour l'alcool, et qu'il n'était pas un héros comme je le croyais à l'âge de 6 ans.

Cette année-là. Il n'avait pas tenu ses engagements et mon cœur d'enfant en fût brisé, dévasté, marqué à vie d'une méfiance des promesses des hommes.

Plus tard et durant toute ma vie, j'ai rencontré des personnes fausses, me promettant des choses et trop souvent j'ai été déçu, fini découragé.

Heureusement à 21 ans, j'ai rencontré mon Père céleste, heureusement, Lui ne joue pas avec nos émotions et encore moins avec nos sentiments. Il ne change pas d'avis du jour au lendemain. Quand il nous promet une chose, cette chose arrive.

(Hébreux 6.18)."...Il est impossible que Dieu mente."

C'est une vérité importante qu'il faut graver dans notre cœur afin de ne jamais l'oublier. Car vie est souvent difficile. Il y a des situations qui peuvent nous décourager, nous décevoir. Mais malgré cela, une vérité demeure…

Dieu, lui, ne nous décevra jamais. Ce qu'il promet, il l'accomplit :

- " Fais de l'Éternel, tes délices, et il te donnera ce que ton cœur désire.

(Psaumes 37 :4-5)Recommande ton sort à l’Éternel, mets en lui ta confiance, et il agira."

Et même qu'il nous parle à travers sa Parole : dans le Prophète Jérémie, chapitre 17 et verset 5 -6 : - " Ainsi parle l'Éternel: Maudit soit l'homme qui se confie dans l'homme, Qui prend la chair pour son appui, Et qui détourne son cœur de l'Éternel ! " 6Il est comme un misérable dans le désert, Et il ne voit point arriver le bonheur; Il habite les lieux brûlés du désert, Une terre salée et sans habitants.…

Si vous me le permettez, je veux prier avec vous :

Seigneur Jésus merci de nous avoir promis le salut et d'avoir été fidèle en donnant ta propre vie sur la croix pour pardonner nos péchés, et en donnant une vie nouvelle en toi. De nous donner de vrais frères et sœurs qui marchent à ta suite.

Seigneur, Jésus, tu ne m'as jamais déçu. Je veux continuellement placer toute ma confiance en toi. Je te pris pour ceux qui écoutent et qu'ils soient saisis de cette vérité fondamentale. La vérité est en toi ! Merci Seigneur Jésus ! Amen.

0 notes

Text

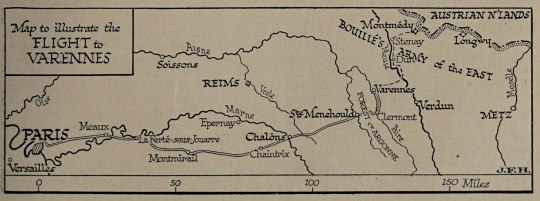

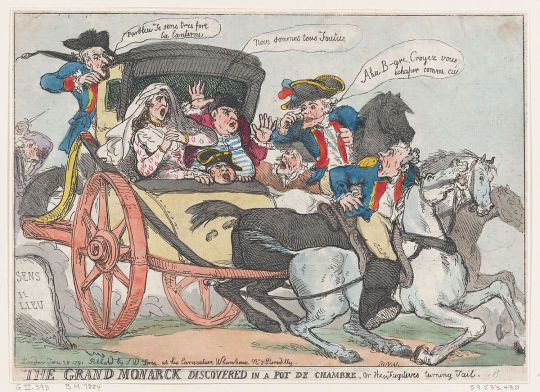

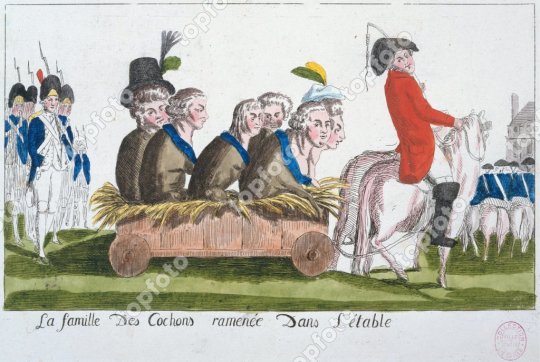

1791-Flight to Varennes

King Louis XVI of France and his immediate family begin the Flight to Varennes during the French Revolution.

The royal Flight to Varennes (French: Fuite à Varennes) during the night of 20–21 June 1791 was a significant event in the French Revolution in which King Louis XVI of France, Queen Marie Antoinette, and their immediate family unsuccessfully attempted to escape from Paris in order to initiate a counter-revolution at the head of loyal troops under royalist officers concentrated at Montmédy near the frontier. They escaped only as far as the small town of Varennes-en-Argonne, where they were arrested after having been recognized at their previous stop in Sainte-Menehould.

This incident was a turning point after which popular hostility towards the French monarchy as an institution, as well as towards the king and queen as individuals, became much more pronounced. The king's attempted flight provoked charges of treason that ultimately led to his execution in 1793.

0 notes

Video

youtube

James Horner / TITANIC • LIVE CONCERT Philharmonique Montmédy

0 notes

Photo

It takes a leap of faith to reach this #church. I will stay on the side of #Enlightenment. You are #free to either jump or stay. #montmédy #meuse #france #ladiagonalleduvide #ruins #urbex #citadel #fortress #wanderlust #églisesaintmartin #broken #bridge #vauban #jumptheysay #digitalnomad #wandering #travellingphotographer #travel #visitmontmédy #grand-est #lorrainegaumaise #lorraine #zombieproof #fortifiedcity (bij La Citadelle De Montmédy) https://www.instagram.com/p/Btf2OErDd47/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=12aj57zhkh4qf

#church#enlightenment#free#montmédy#meuse#france#ladiagonalleduvide#ruins#urbex#citadel#fortress#wanderlust#églisesaintmartin#broken#bridge#vauban#jumptheysay#digitalnomad#wandering#travellingphotographer#travel#visitmontmédy#grand#lorrainegaumaise#lorraine#zombieproof#fortifiedcity

0 notes

Photo

Motmédy Citadel... by kali_merette2002 http://flic.kr/p/UCFM3u

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

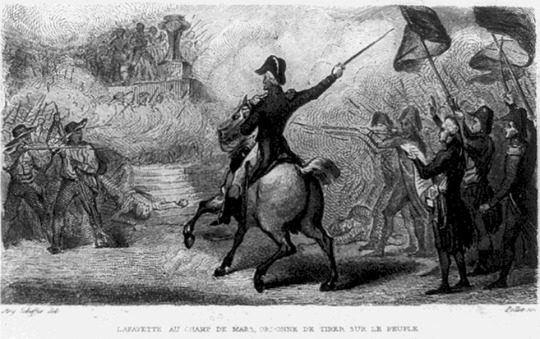

The Champ de Mars Massacre

Your back is aching, your muscles ache. The past days, no, weeks, you have helped to level the Champ de Mars, you have helped to fill up the puddles, to raise tribunes - all that hard labour for this day. The 14th of July 1790. To the day one year prior you were amongst the crowd that stormed the Bastille. Today is the anniversary of your Revolution. Thousands upon thousands of people have gathered today to celebrate. Not just from Paris but from all over France. Every Department and every Province has send its people, has send representatives and soldiers - their banners fly in the breeze. You here the people shout and roar “Vive le roi! Vive la reine!” and you join in in the jubilation as does your beloved right next to you. “Vive le roi! Vive la reine!” The members of the National Assembly stand together on the Champ the Mars, the King is there as well with his family, an altar had been erected in the middle of the field. General La Fayette rides in on his white stallion. He is the Hero of Two Worlds, the knight of the Revolution, the champion of the people - or so you fought then.

It is a hot and sunny day in July once again - but a whole year has passed. It is the 17th of July, a Sunday, a holy day. People have gathered on the Champ de Mars and this time it is not in celebration. The people are angry, they feel betrayed. This year, in 1791, thousands upon thousands have gathered to sign a petition, a petition to put the king on trial for the crimes he had committed against his people. Everything seemed orderly enough at first but then the people spotted two men hiding under the altar that still stood there from the celebration of 1790. The crowed fought there were spies and so they decapitated them and put their heads on spikes. Everything went downhill from there on. Troops of the National Guard arrived, the mayor of Paris, Monsieur Bailly arrives, martial law is declared, the soldiers are firing at the crowed and miss, the crowed throw stones at the troops, the soldiers fire again - they hit their targets this time, You see people fall, women, and man and children - god, they are firing at the children too! The crowed dispenses, all is confusion and hurry now, your beloved is no longer by your side as you start to run. There is shouting about a cannon that is supposedly about to be fired. More people fall. As you hurry to safety, you turn around one last time and see General La Fayette standing by his National Guard as they fire into the crowed. Is that what has become of the peoples hero?

Within little more than a year La Fayette went from the zenith of his influence and popularity to a record low. In 1790, during the Fête de la Federation, his carefully put together image had been approved by the people of France. In 1791 however, with the Champ de Mars Massacre, his image began to suffer severely and he had in great parts lost the love of the people. Right when it happened, the events of July 17, 1791 were used for propaganda from ever party and every side. It was played-down, blown out of proportions, made into something it was not, numbers and details were changed to make one group look more or less guilty. What remained though was the fact that La Fayette was at the centre of the events. His exact role in the massacre as well as everything that happened that day is often hard to determine, exactly because the massacre was so heavily used for political and propaganda purposes at the beginning. So here is a little overview about the things we know or at least thing we know.

What Happened? - The Context:

The officials had expected large protests on the 14th of July, the anniversary of the Revolution but the 14th passed rather peaceful. On the 17th however, the atmosphere started to heat up. Barely a month before, from July 20 to July 21, the King, Louis XVI, the Queen, Marie Antoinette, their children and other immediate members of the Royal Family had tried to flee from Paris to Montmédy. The flight failed and they were recognised and stopped in Varennes-en-Argonnne and after that brought back to Paris. La Fayette and other government officials tried to present the events as an attempted kidnapping of the King - that was of course complete nonsense, there was no kidnapping whatsoever and everybody knew that. The flight to Varennes painted La Fayette in a particular bad light for two reasons. First, there had been rumours of a possible escape by the King long before the actual attempt was made. It was La Fayette, among others, who had time and time again sworn that the King would not attempt to flee. He had accepted the constitution, he had become a monarch under the constitution and would not betray the loyalty of the French people in such a fashion. Second, it was the National Guard under the command of La Fayette who was tasked with safeguarding the King - and making sure that he would not escape. Their failure shed a very bad light on La Fayette. At best his guard was undisciplined and he had not enough control over them. At worst, he was fully aware of the royal families’ plans and aided them by instructing the guardsmen to look the other way.

On July 17, a petition had been drafted and the people were called upon to assemble and to sign the petition. This endeavour was first backed by the Jacobins but leading members later withdraw the support of the Jacobins as they had been urged by Robespierre himself to so. It was too little and too late however, as many people in the crowd that day would have identified as Jacobins.

The undersigned Frenchmen, members of the sovereign people, considering that, in questions concerning the safety of the people, it is their right to express their will in order to enlighten and guide their deputies,

That no question has ever arisen more important than the King's desertion,

That the decree of 15 July contains no decision concerning Louis XVI,

That, in obeying this decree, it is necessary to decide promptly the future of this individual,

That his conduct must form the basis of this decision,

That Louis XVI, having accepted Royal functions, and sworn to defend the Constitution, has deserted the post entrusted to him; has protested against that very Constitution in a declaration written and signed in his own hand; has attempted, by his flight and his orders, to paralyze the executive power, and to upset the Constitution in complicity with men who are today awaiting trial for such an attempt,

That his perjury, his desertion, his protest, not to speak of all the other criminal acts which have proceeded, accompanied, and followed them, involve a formal abdication of the constitutional Crown entrusted to him,

That the National Assembly has so judged in assuming the executive power, suspending the Royal authority and holding him in a state of arrest,

That fresh promises from Louis XVI to observe the Constitution cannot offer the Nation a sufficient guarantee against a fresh perjury and a new conspiracy.

Considering finally that it would be as contrary to the majesty of the outraged Nation as it would be contrary to its interest to confide the reins of empire to a perjurer, a traitor, and a fugitive, [we] formally and specifically demand that the Assembly receive the abdication made on 21 June by Louis XVI of the crown which had been delegated to him, and provide for his successor in the constitutional manner, [and we] declare that the undersigned will never recognize Louis XVI as their King unless the majority of the Nation express a desire contrary to the present petition

What happened next could have come straight out of a comedy - were it not to trigger a bloodbath. The crowed that had assembled that day spotted two “suspicious man”. Now, we do not know who this men were or what they intended - in all likelihood they just sat there and tried to relax and sleep, maybe find some shade on such a hot day, maybe all they wanted was to get a peek under the skirts of the women who had assembled as well. They hide behind the altar that had been left from the Fête de la Federation and this behaviour prompted the crowd to assume that they were spies who wanted to denounce the people present. The crowed attacked the men, beheaded them and paraded their head around on spikes. The crowed, who had previously already worried the Parisian officials, now had committed two murders. It is from this point on, that things get a bit more tricky.

What Happened? - The actual Massacre:

We start this portion of the post with an excerpt from La Fayette’s Memoirs to form a basis.

The affair of the Champ de Mars has been misrepresented with an extraordinary degree of audacity ; it became the pretext for the sufferings to which the magnanimity of the virtuous Bailly was so long exposed in that capital to which he had devoted himself during the whole course of a very difficult magistracy, with an affectionate and enlightened zeal. (…)

The 14th of July the anniversary of the confederation was celebrated. All appeared tranquil. But the 17th of July, a meeting took place in the Champ de Mars, to sign the petition drawn up by Laclos, and corrected by Brissot.

Two invalids, who, from a feeling of idle curiosity, had concealed themselves under the altar of the country, were seized ; their heads were cut off, and placed on two pikes, to be exhibited through the streets of Paris. The commander-in-chief [La Fayette] hastened to the spot, with a detachment of national guards. The rioters, with some ringleaders at their head, formed a barricade around themselves with carts ; across one of these carts a man pointed a musket at the commander-in-chief, but it missed fire. The national guards, springing over the barricade seized the culprit, and dragged him towards the commander-in-chief, who ordered him to be set at liberty. It is well known that the jacobins imputed the deliverance of this assassin to a concerted scheme, until he came forward, himself to boast of his conduct at the bar of the convention. The people who surrounded the altar, and some of those who were in the Champ de Mars, promised the commander and two commissaries of the commons to separate, after having peaceably signed the petition, for no person had ever thought of opposing that signature.

Several hours thus passed ; a detachment of the national guard had been stationed outside the Champ de Mars to watch over any hostile movements that might occur, and it was thought at the Hotel de Ville that all would pass quietly, when some persons came to denounce to the assembly the real projects of the rioters against the assembly itself. They intended doing what has been done since, on the 10th August, 31st May, and 4th prairial.

The national assembly decreed that the mayor of Paris should take measures to secure their safety, that of the Tuileries, and of the capital. It was in consequence of the unanimous injunctions of that same assembly that the mayor of Paris and the council of the commune published martial law. M Bailly sallied forth at the head of a battalion of grenadiers, which performed duty each day at the Hotel de Ville, to proceed, as a reserve corps, to the place in which public order was most disturbed ; the commander-in-chief, to whom information of this step was given, joined them on the road.

They presented themselves before the entrance of the Champ de Mars, and were received with a shower of stones ; some fire-arms were also used ; a pistol was fired at the mayor whom the ball narrowly missed, when he was on the point of making his proclamation. During this attack, the national guard fired in the air to avoid wounding any one ; but the assailants, emboldened by this moderation redoubled their attack against the municipal officers and national guards, of whom some were wounded, and amongst the number an aide-de-camp ; two volunteer chasseurs were killed ; the national guard then fired in earnest. The loss that ensued on the part of the assailants has been most grossly exaggerated ; the rioters were dispersed principally by the cavalry, who did not use their arms.

All the events that he describes, happened that way - it is however questionable if they happened exactly that way. What also comes to mind is La Fayette’s phrasing of the events: he wrote that the National Guard did certain things but never what his actual orders were. This vague language is quite crucial in understanding his part in the whole event. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

In short, while we can be reasonably sure that somebody did indeed shot at La Fayette, we can not be completely sure if that happened during the first or second encounter between the Guard and the crowed. La Fayette would not have gained much from placing the attack on him at an earlier hour so we are going to believe him with that. It is also unsure how much time exactly passed when La Fayette wrote “several hours”. But these details are rather minor and even if they were wrongly reported, do not change the outlook on the event as a whole. More interesting is the question about the declaration of Martial Law. La Fayette presents it as if he had nothing to do with it while other sources claim that he was among the men urging Mayor Bailly to do so.

On to the most interesting part. Who gave the order to fire and when was this order given?

La Fayette claims that the he and his guard were attacked with stones and that during this attack he ordered his men to fire warning shots into the air (in his memoirs he is not as clear about it as in earlier statements were he admitted that he ordered his men to fire into the air - but solely into the air). Other accounts say that the crowed only threw stones after the guardsmen had shot at them while again different sources claim that the soldiers never fired into the air but directly at the people. Whatever happened, at one point the Guard did indeed fire at the people. Now, La Fayette was eminent that he never gave that order - and I think I believe him. Such an action would not be typical for him. But who could have given the order? Some sources state that Bailly gave the order and because he was Mayor, the National Guard followed his order. Again, other reports state that nobody gave the order and that the soldiers just fired on their own.

I find all of these reports questionable. The most logical explanation would be that La Fayette, as commander-in-chief gave the command. But as I stated earlier, I have great trouble imaging that … maybe I am biased but I just can not see La Fayette giving such a command. I also do not believe that Bailly gave the order. I could imagine that the Guard shot on its own. Maybe one of the men was frightened and pulled the trigger, maybe even by accident or in an act of self-defence, and his comrades followed suite, thinking that there had been an order - then again, what are the probabilities of that happening?

Several sources mention that La Fayette tried to stop his troops as soon as he realised what had happened. One report even claimed that he physically put himself between the crowed and a cannon that was about to be fired. He did not however mention any of these actions in his Memoirs. If there was massacre on the civilian population and you tried to prevent or at least end this massacre, you would mention that in your Memories, would you not?

Where does of all of that leaves us? In the worst case, La Fayette actively ordered his guards to fire into a mostly unarmed civilian crowed. In the “best” case, La Fayette did not order the massacre himself but had too little control and influence over his own troops that he could not prevent the event from happening. Because, as Tom Chaffin put it in his book Revolutionary Brothers:

Whatever actually happened that day, the gunfire escalated into a lethal fusillade that left many demonstrators dead or wounded.

In any event, La Fayette was judged severely by the public.

The number of victims of the Champ de Mars massacre vary dramatically. Contemporary sources state that there were several thousand victims while modern scholars estimate the number of dead between 50 and 100 and the number of wounded between 100 and 1000. It is however next to impossible to ever be able to determine these numbers correctly.

The immediate public and political reactions on and after the 17th varied widely but were generally devastating for La Fayette. I may make an extra post about the reactions because otherwise this post would get too long. As a last thought, I want to quote from the Memoirs of La Fayette’s youngest daughter, Virginie, how she remembered that day.

The Jacobins raised on the 17th of July a considerable outbreak. The brigands commenced by murdering two men. Martial law was proclaimed. It is difficult to form an idea of my mother's mortal anguish while my father was in the Champ de Mars exposed to the rage of an infuriated multitude which dispersed crying out that my mother must be put to death and her head carried to meet him. I remember the fearful cries we heard, I remember the alarm of every body in the house, and above all my mother's joy at the thoughts that the brigands who were coming to attack her were no longer surrounding my father in the Champ de Mars. While embracing us with tears of joy, she took every necessary precaution against the approaching danger with the greatest calmness and above all with the greatest relief of mind. The guard had been doubled, and was drawn up before the house, but the brigands were very near entering my mother's apartment by the garden looking upon the place du Palais-Bourbon, and were already climbing the low wall which protected us, when a body of cavalry passed on the place and dispersed them.

#marquis de lafayette#lafayette#general lafayette#historical lafayette#french history#french revolution#1790#1791#on this day in history#france#bailly#paris#robespierre#14 juillet#14 july#17 july#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#virginie de lafayette#national guard#champ de mars#massacre#art#louis xvi#marie antoinette#fete de la ferderation#georges washington de lafayette

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

D'Auby. Henri. 48 (ou 49) ans, né à Montmédy (Meuse). Menuisier. Anarchiste. 28/2/94., Alphonse Bertillon, 1894, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Photography

Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005

Size: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Medium: Albumen silver print from glass negative

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/306756

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

749,000 €

453m² / 4876 ft²

Montmédy, Meuse, Grand-Est, France.

#beautiful house#modern#kitchen#bedroom#mezzanine#corridor#bay window#stove#fireplace#mantelpiec#attic room#exposed beams#french#montmedy#meuse#lorraine#grand-est#france

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One word of command from Louis to clear the way for him at the sword's point would yet have been sufficient; but he had still the same invincible repugnance as ever to allow blood to be shed in his quarrel. He preferred peaceful means, which could not but fail. With a dignity arising from his entire personal fearlessness, he announced his name and rank, his reasons for quitting Paris and proceeding to Montmédy; declaring that he had no thought of quitting the kingdom, and demanded to be allowed to proceed on his journey. While the queen, her fears for her children overpowering all other feelings, addressed herself with the most earnest entreaties to the mayor's wife, declaring that their very lives would be in danger if they should be taken back to Paris, and imploring her to use her influence with her husband to allow them to proceed.

The Life of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France - Charles Duke Yonge

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reading Treasure: What They Said Saturday: "I will write to you soon–if I can."

In the immediate aftermath of the royal family's failed flight to Montmédy, their friends and loved ones who either knew about the flight or had heard about it when the news broke out in Paris were left with great uncertainty as to the royal family's fate. As with any incident involving the royal family, rumors abounded. Were they to be killed? Imprisoned? As soon as they were able, the members of the royal family had letters sent (or in some cases, smuggled) out of the Tuileries to let their closet friends know that they were still alive. Uncertain--but alive.

14 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Assemblée constituante, séance du 15 juillet 1791 (AP, t. XXVIII, p. 331-332)

M. Muguet de Nanthou, rapporteur : Voici, maintenant, Messieurs, l’article 1er du projet du comité.

« L’Assemblée nationale, [...] décrète

« 1° Qu’il y a lieu à accusation contre ledit sieur de Bouillé, ses complices et adhérents, et que son procès lui sera fait et parfait devant la haute cour nationale provisoire, séant à Orléans ; qu’à cet effet les pièces qui ont été adressées à l’Assemblée seront envoyées à l’officier faisant, auprès de ce tribunal, les fonctions d’accusateur public. »

M. Robespierre : J’ai l’honneur de proposer un amendement qui sera sans doute dans les principes des comités, c’est que tous les coupables du délit dont vous vous occupez soient dénoncés et poursuivis. Je demande par exemple aux comités, je demande aux plus zélés partisans de leur système de quel droit on excepte dans le décret les personnes qui ne sont pas inviolables ; je veux parler de Monsieur, frère du roi, par exemple. (Applaudissements ; murmures et interruptions.)

[...]

Y a-t-il de plus forts indices contre les trois gardes du corps qui ont suivi le roi, et qui n’ont fait qu’accompagner leur maître, qu’il n’y en a contre Monsieur, frère du roi, dont la fuite a été combinée avec la sienne dans les pays étrangers, dans le sein de nos ennemis ? Qu’on me dise si les soupçons ne doivent point porter spécialement sur un personnage plus intimement lié au roi, mais qui n’est pas inviolable comme lui ? Messieurs, prenez-y bien garde, si vous faites une exception aussi étrange, aussi évidemment contraire à tous les principes, il est évident que vous vous exposez au reproche d’avoir éternellement épargné les conspirateurs puissants ; et l’on remarquera avec étonnement que la seule victime immolée au salut du peuple, était précisément une victime d’un rang inférieur, que l’opinion a cru être immolée à ce même homme qui a fui avec le roi. (Murmures.)

J’ai l’honneur de vous observer que, de quelque manière que vous prononciez sur le roi lui-même, il faut prononcer. Il est de votre bonne foi, il est de votre loyauté de prononcer, non pas d’une manière tacite, mais d’une manière expresse.

Un membre : On rentre dans la discussion.

M. le Président : Laissez finir.

M. Robespierre : Ces réflexions me paraissent si simples, il me paraîtrait si contraire à la gloire de l’Assemblée, au droit de la nation, de s’en écarter, que si vous n’adoptez pas ma proposition, je me crois, en vertu du serment qui me lie à l’Assemblée nationale et encore plus pour l’honneur de la nation, obligé de protester contre la détermination que vous allez prendre. (Murmures prolongés.)

M. Prieur : Sans ce que vient de dire M. Robespierre, je n’aurais pas pris la parole. Remarquez bien que la complicité du frère du roi est tellement démontrée, que le roi a dit positivement, dans une seconde déclaration, si je m’en rappelle bien, que Monsieur devait venir le joindre à Montmédy, et qu’il n’avait pris une autre route qu’afin de ne pas manquer de chevaux. (Murmures.)

#il y a 228 ans#Révolution française#15 juillet 1791#Robespierre#Prieur de la Marne#Assemblée constituante#1791#Pierre Louis Prieur#Muguet de Nanthou#crise de Varennes

6 notes

·

View notes