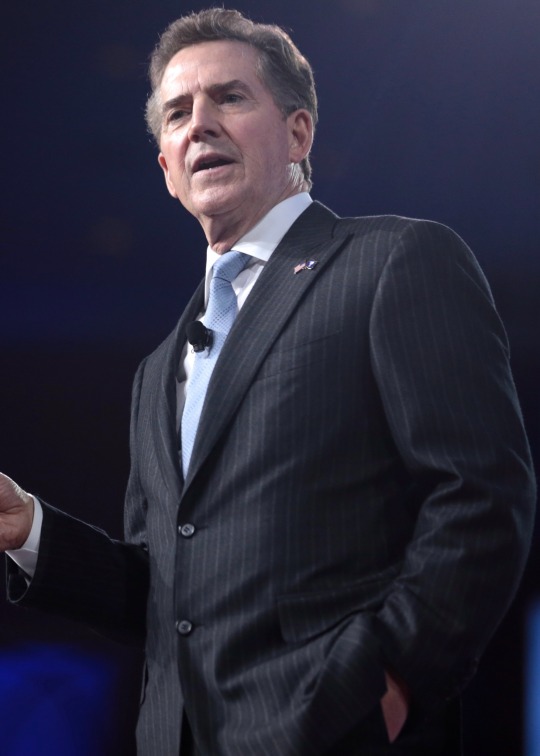

#Jim DeMint

Text

Jim DeMint

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#men in suits#suited daddy#suited grandpa#suitedman#suit daddy#silverfox#suitfetish#buisness suit#suited men#suitedmen#suited man#americans#republicans#member of congress#us senator#south carolina#Jim DeMint

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steps from the Capitol, Trump allies buy up properties to build MAGA campus | The Washington Post

At first glance, the flurry of real estate sales two blocks east of the U.S. Capitol appeared unremarkable in a city where such sales are common. In the span of a year, a seemingly unrelated gaggle of recently formed companies bought nine properties, all within steps of one another.

But the sales were not coincidental. Unbeknown to most of the sellers, the limited liability companies making the purchases — a shopping spree that added up to $41 million — are connected to a conservative nonprofit led by Mark Meadows, who was Chief of Staff to President Donald Trump. The organization has promoted MAGA stars like Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) and Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.).

The Conservative Partnership Institute, as the nonprofit is known, now controls four commercial properties along a single Pennsylvania Avenue block, three adjoining rowhouses around the corner, and a garage and carriage house in the rear alley. CPI’s aim, as expressed in its annual report, is to transform the swath of prime real estate into a campus it calls “Patriots’ Row.”

The acquisitions strike some Capitol Hill regulars as puzzling, considering that Republicans have long made a sport of denigrating Washington as a dysfunctional “swamp,” the latest evidence being a successful GOP-led effort to block local D.C. legislation to revise the city’s criminal code.

“So you don’t respect how we administer our city and then you secretly buy up chunks of it?” said Tim Krepp, a Capitol Hill resident who works as a tour guide and has written about the neighborhood’s history. “If it’s such a hellhole, go to Virginia.”

Reached on his cellphone, Edward Corrigan, CPI’s president, whose name appears on public documents related to the sales, had no immediate comment on the purchases, which were first reported by Grid News and confirmed by The Washington Post. “I’ll get back to you,” Corrigan said. He did not respond to follow-up messages.

Former senator Jim DeMint, CPI’s founder, and Meadows, a senior partner at the organization, did not respond to emails seeking comment. Cameron Seward, CPI’s general counsel and director of operations, whose name appears on incorporation documents related to the companies making the purchases, did not respond to a text or an email.

As Congress’s neighbors, denizens of the Capitol Hill neighborhood are accustomed to existing in close quarters with all varieties of official Washington. Walk the neighborhood and you might catch a glimpse of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) or former Trump strategist Stephen K. Bannon, among those who own homes near the Capitol. The Republican and Democratic national committees both have offices in the neighborhood.

But it’s rare, if not unprecedented, for a nonprofit to purchase as many properties in such proximity and in so short a period of time as CPI has assembled through its related companies, a roster with names like Clear Plains Holdings, Brunswick Partners, Houston Group, Newpoint and Pennsylvania Avenue Holdings. The companies list Seward as an officer on corporate filings, as well as CPI’s Independence Avenue headquarters as their principal address.

Now, in what may be an only-in-Washington vista, a single Pennsylvania Avenue block is occupied by Public Citizen, the left-leaning consumer advocacy group, the Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank, and CPI, which bought four properties through its affiliates.

In addition to the nine D.C. parcels CPI’s network has bought since January 2022, another affiliated company, Federal Investors, paid $7.2 million for a sprawling 11-bedroom retreat on the Eastern Shore. In 2020, CPI, under its own name, also spent $1.5 million for a rowhouse next to its headquarters, which it leases, a few blocks from the Capitol.

DeMint, a former Republican congressman from South Carolina, started CPI in 2017, shortly after he was ousted as Heritage’s leader amid criticism that the think tank had become too political under his direction. Meadows joined in 2021, after working as Trump’s Chief of Staff. He was by Trump’s side during the administration’s final calamitous days, before and after the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol and as the President’s allies were seeking to overturn election results.

On its 2021 tax returns, CPI reported $45 million in revenue, most of it generated through contributions and grants, and paid DeMint and Meadows compensation packages of $542,000 and $559,000, respectively. Its current offices, a three-story townhouse at the corner of Third Street and Independence Avenue SE, is a hub of GOP activity. During the chaotic lead-up to Rep. Kevin McCarthy’s election as House Speaker, dissident Republican lawmakers were observed congregating at CPI.

CPI also provides grants to a cluster of nonprofits headed by Trump allies. Former Trump adviser Stephen Miller, for example, leads America First Legal, which received $1.3 million from CPI in 2021 and bills itself as a check on “lawless executive actions and the Radical Left.”

Cleta Mitchell, an attorney who was on the call Trump made to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger seeking to reverse votes in the 2020 election, runs what the organization bills as its “Election Integrity Network,” which has cast doubt on the validity of President Biden’s 2020 victory.

“The election was rigged,” EIN tweeted last July. “Trump won.”

CLOSE TO THE CAPITOL

At an introductory meeting in December, recalled Gerald Sroufe, an advisory neighborhood commissioner on Capitol Hill, a CPI representative said the group planned to move its headquarters to a three-story building it had bought on Pennsylvania Avenue, next to Heritage’s office. Until the pandemic forced it to close, the Capitol Lounge had occupied the 130-year-old building. The bar had served a nightly bipartisan swarm of congressional staffers and lobbyists for more than two decades.

The CPI official, Sroufe said, indicated that the group planned to use the new Pennsylvania Avenue properties to “expand” its offices and “provide new retail.” But the official made no mention of Patriots’ Row, Sroufe said, or the three rowhouses the group’s affiliates had bought around the corner on Third Street SE. All of the properties are in the neighborhood’s historic district, which protects them from being altered without city review.

“This is much grander than what we were talking about,” Sroufe said after learning from a reporter about the other purchases. “On the Hill, people are always talking about how wonderful it is to be close to the Capitol and Congress. It’s kind of like a curse.”

As in many commercial corridors hit hard by the pandemic, businesses along Pennsylvania Avenue have struggled over the past couple of years. Tony Tomelden, executive director of the Capitol Hill Association of Merchants and Professionals, said CPI could energize a strip pocked with vacant storefronts.

“I welcome any business because the only thing opening right now are marijuana shops,” said Tomelden, an H Street NE bar owner who helped open the Capitol Lounge in 1996 and, as it happens, instituted a rule that patrons could not talk politics while imbibing. “If they’re going to pay a lot of money and raise property values, I’m all for it. I don’t care about anybody’s politics as long as they pay their tab.”

In an overwhelmingly Democratic city, finding those who are less sanguine about CPI’s growing footprint is not exactly difficult.

Yet politics is only part of the issue, as far as Krepp is concerned. CPI’s purchases, he said, threaten the area’s neighborhood vibe, as would be the case if any group, no matter its ideological leaning, bought as many properties. “I don’t want to create another downtown on Capitol Hill,” he said. “There’s a glut of available office space downtown. You don’t have to buy up neighborhoods.”

Rep. Jamie B. Raskin (D-Md.), a regular commuter to the Capitol from his home in Montgomery County, sees CPI’s acquisitions in terms more political than geographic.

“It just seems like a massive real estate coming-out party for the extreme right wing of the Republican Party,” Raskin said. “This is a very explicit and well-financed statement of intent. They set out to take over the Republican Party and they’re very close to clenching the power.”

Instead of Patriots’ Row, Raskin suggested an alternative name: Seditionist Square.

“Maybe Marjorie Taylor Greene can be their advisory neighborhood commissioner,” he said.

A ‘PERMANENT BULWARK’ IN D.C.

On its 2021 tax return, CPI said its mission is to be a “platform” for the “conservative movement,” and to provide “public policy” training for “government and nonprofit staffers” and meeting space for gatherings and policy debates.

Although not required to identify donors, CPI reported seven contributions in excess of $1 million, including one of more than $25 million. Trump’s Save America political action committee gave $1 million in 2021, according to campaign finance records. Billionaire Richard Uihlein, a major Republican donor, gave $1.25 million a couple of years ago through his foundation, records show.

A CPI-related entity, the Conservative Partnership Center, rented space to two political action committees as of early January, the House Freedom Fund and Senate Conservative Fund, according to campaign finance records. CPI also received $4,000 from Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), who has recorded his “Firebrand” podcast at the group’s studio, as has the host of the “Gosar Minute,” Rep. Paul A. Gosar (R-Ariz.), according to the group’s annual report. Greene paid CPI $437.73 for “catering for political meetings” in 2021, the records show.

“No one stood up to the Left as courageously as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene,” CPI declared in its 2021 annual report, hailing her as a “hero” who “endured sexist fury that always lurks just beneath the progressive surface.” The report described Boebert as a “gun rights advocate” who “wants to protect our environment more than anyone else.”

It was in CPI’s 2022 annual report that the group briefly referred to its expansion plans, writing that it has strengthened “its ability to serve the movement by beginning renovations to Patriots’ Row on Pennsylvania Avenue.”

“In 2022, the Left tried to drag America further into a dark future of totalitarianism, chaotic elections and cultural decay,” the report asserts in an introduction from DeMint and Meadows. “The Washington establishment, per usual, did nothing to stop them. But neither the Left nor the establishment could stop the culture and community we’re building here at the Conservative Partnership Institute.”

“With our expanded presence in D.C.,” they add, “we’re launching CPI academy — a formal program of training for congressional staff and current and future members of the movement.”

“Even if we can’t change Washington, we can create a permanent bulwark against its worst tendencies.”

A SPATE OF SALES

CPI began its expansion in 2020, purchasing the rowhouse next door to its headquarters and christening it “The Rydin House” for Mike Rydin, a construction magnate and prominent conservative donor. When Federal Investors bought the Eastern Shore property, the group named it “Camp Rydin.”

On Capitol Hill, several property owners who sold their buildings to CPI-linked companies were surprised to learn that the buyers were connected to a group led by Meadows and DeMint.

“I did not know,” said Jacqueline Lewis, who sold a townhouse on Third Street SE to 116 Holdings for $5.1 million in July. The company’s officer, according to its corporate filing, is Seward, and the principal address it lists is the same as CPI’s headquarters. A trust document related to the transaction is signed by Corrigan, CPI’s president.

Brunswick Partners, which lists CPI and Seward as contacts on its corporate filing, bought the neighboring rowhouse for $1.8 million in January, according to property records. Brian Wise, the seller, said he did not know of the company’s CPI connection. An attorney who approached him and his wife, he said, “asked if we were willing to sell and we agreed on a price. It was a business sale.”

Keith and Amanda Catanzano also were unaware of CPI when they sold a garage in the alley behind Third Street SE to Newpoint for $1 million in June. Newpoint lists Seward as an officer and the same mailing address as CPI. “We had no idea,” said a woman who answered the phone at a number listed for the Catanzanos before hanging up.

Eric Kassoff, who sold the former site of the Capitol Lounge to Clear Plains, said he knew of the company’s CPI ties before the $11.3 million deal was finalized in January. He also sold the group a carriage house behind the building for $400,000.

Kassoff said he did not want to lease the space to a fast-food restaurant or a convenience store. He said CPI’s political leanings were not a factor in his decision to sell to the organization.

“Why would I have any issue selling my property to proud Americans?” asked Kassoff, who described himself as an independent. “We need to get past the labeling and demonizing and talk to each other, and that’s true in politics as well as commerce. If we were all to take that position we wouldn’t have much of a country left, would we?”

Although the Capitol Lounge closed more than two years ago, vestiges of its past remain on the building’s exterior, including a rendering of Benjamin Franklin beneath a quote concocted by the bar’s founder, Joe Englert: “Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.”

James Silk, the bar’s former owner, said he left behind memorabilia when he vacated the building that could be suitable for the new owner: Richard M. Nixon campaign posters still hanging on the walls of what the owners cheekily dubbed the Nixon Room (located across from the Kennedy Room).

“Nixon is finally with his people,” Silk said. He laughed and added: “Nixon was a Republican, right?”

#us politics#news#the washington post#republicans#conservatives#gop#mark meadows#Conservative Partnership Institute#political action committees#washington dc#Patriots’ Row#Jim DeMint#Cameron Seward#heritage foundation#capitol hill#America First Legal#Election Integrity Network#steve bannon#Cleta Mitchell#Capitol Lounge#Save America pac#Richard Uihlein#Conservative Partnership Center#House Freedom Fund#Senate Conservative Fund#Rep. Matt Gaetz#firebrand podcast#Gosar Minute#rep. paul gosar#Mike Rydin

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in History: December 6, 13th Amendment is ratified

Today in History: December 6, 13th Amendment is ratified

Today in History

Today is Tuesday, Dec. 6, the 340th day of 2022. There are 25 days left in the year.

Today’s Highlight in History:

On Dec. 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, abolishing slavery, was ratified as Georgia became the 27th state to endorse it.

On this date:

In 1790, Congress moved to Philadelphia from New York.

In 1907, the worst mining disaster in U.S. history…

View On WordPress

#accidents#Accidents and disasters#Ben Watt#Craig Brewer#Don Nickles#Donald Trump#explosions#General news#Government and politics#Industrial accidents#Jim DeMint#Judd Apatow#Legislature#Mining accidents#Steven Wright#Tom Hulce#Vladimir Put

0 notes

Text

GREENVILLE — When former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson and former U.S. Sen. Jim DeMint took to a Bob Jones University stage on May 2, their discussion on education happened at the same time as the regular meeting of the Greenville County GOP.

In years past, such Republican figures of national significance would have spoken in front of the county party, before a well-documented and bitter leadership takeover a year ago led to fractures at both the local and state level.

Now, the split has created a new Upstate political organization, the Fourth District Republican Club, which hosted the event at a packed BJU performance hall.

The Republican party break in Greenville County has revolved around a distilled issue: Who is most loyal to former President Donald Trump?

New leadership that was energized in the weeks after Trump's loss and amid claims of a rigged election has branded itself as a movement that has injected grassroots energy. They pushed out so-called "establishment RINOs" — Republicans in name only — who are framed as having betrayed the ideals of the GOP's current standard-bearer.

A year into the loyalty purge, the new Fourth District club watches and waits, replete with elected Republicans whose power is entrenched and who have found a new outlet for their political activism.

The result was expected, said Nate Leupp, president of the club and former head of the county party up until last year, when he didn't seek reelection.

County party meetings have at times devolved into shouting and physical confrontations, dwindling membership and leadership resignations, including the secretary, treasurer and the party executive committeeman.

"The local county party is imploding at a faster pace than we expected," Leupp told The Post and Courier. "We're right at one year right now, and they seem to be doing a very good job of imploding."

It's a characterization county GOP Chairman Jeff Davis said is inaccurate and is more evidence of "controversy seeded by the establishment."

The county party is powered by the passion of everyday activists, which unlike politicians entrenched in power results in spirited disagreement, Davis told The Post and Courier.

Davis pointed to an event being held May 6-7, "Rock the Red," backed by county party leaders that will feature speakers characterized as true MAGA supporters. Keynote speakers will be Lara Trump, who is Trump's daughter-in-law, MyPillow founder Mike Lindell and former close Trump advisor Roger Stone.

"They're trying to bifurcate and be divisive within the Republican Party," Davis said of the Fourth District club. "We find it amusing. I don't know how they will grow."

The saga began in the weeks following Trump's November 2020 loss to President Joe Biden and unproven claims of widespread voter fraud.

Powered by the conspiracy theory, more people began to attend county GOP meetings in greater numbers, facilitated by a group Davis and others started, MySCGOP. It happened just as the party conducted its reorganization that occurs every two years.

In April 2021, a three-person slate of candidates backed by traditional party leaders was elected to lead the county apparatus, a vote conducted virtually because of the pandemic and before widespread distribution of vaccines.

A faction billing itself as the "MAGA slate" objected, claiming a rigged process. The faction met in person in a Greenville hotel ballroom that day and submitted paper ballots.

The MAGA slate lost in a close race, but come summer the insurgent group applied enough pressure to prompt the leadership's resignations. That's when Davis came into power, along with state executive committeeman Pressley Stutts, who a month later died due to COVID-19.

Throughout the course of the year, the county party led protests against vaccine mandates, acceptance of election results, detainment of some of those accused of participating in the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol riot and a host of other far-right issues.

The county party at one point changed the party logo to feature Trump's signature swooping, orange combover.

Supporters of a “MAGA slate” of three running for Greenville County GOP positions pray for victory inside a packed Greenville Hilton ballroom on April 14, 2021. The group ultimately gained control of the county party after the previous leadership resigned. File/Eric Connor/StaffBy Eric Connor [email protected]

Along the way, Leupp and others have stoked the flames within the county leadership. They posted video, for instance, in which a face-to-face confrontation during a meeting caused people to leave and ended without a quorum to vote.

In December 2021, Davis was censured by the South Carolina Republican Party's executive committee for what state party chairman Drew McKissick said were false statements and harassment, including a host of lawsuits, against other Republicans.

The censure was a theatrical display orchestrated to undermine leadership the established Republicans wanted to see fail, thereby "quashing the Average Joe Republicans," Davis said.

The rift has birthed dueling claims of which group is, in fact, a collection of party imposters.

“Are these people really supporting the Republican party and the Republican platform," Davis said, "or are they supporting their own fiefdoms?”

Leupp said the county group represents a more-fringe "QAnon group" who are apologists for the Capitol insurrection and claim allegiance to Trump even though the former president has endorsed congressional candidates in the upcoming June primaries that the group considers established elites.

"That's more the type that came out and got engaged a year ago, and now a lot of them are gone," Leupp said.

Following the split, McKissick endorsed new outlets so that party members and elected officials who used to participate in party meetings could find an outlet — and counter the current county group's ambitions of taking over the state party.

Trump endorsed McKissick in his race for state party chairman against challenger Lin Wood.

Recently, the former president threw his support behind District 4 U.S. Rep. William Timmons against challenger Mark Burns, an Easley pastor speaking at the "Rock the Red" event who was an advisor to Trump during the 2016 South Carolina primary.

"To them, establishment means anybody who's been there five minutes before them," McKissick told The Post and Courier. "You can only keep motivated with nothing but anger for so long. While the Fourth District club has been growing, the county party has been shrinking."

Davis said he and other county party leaders were surprised that Trump didn't endorse Burns or at least remain neutral, but in any case doesn't want to emulate the club's events that host prominent elected leaders.

“I don’t want a bunch of politicians coming in there," he said. "We’re not a rah-rah crew for the elected establishment politicians.”

The Fourth District club will wait and see what fate awaits the county party before any decision to potentially rejoin, which would come next March when the two-year reorganization process is once again in play, Leupp said.

“I don’t know the answer right now," he said. "Things are going very well with our club. That doesn’t mean we don’t want to come back in. We just don’t want them taking over and representing South Carolina at the national level, which would be the joke of the nation.”

"That's all well and good," Davis said, "but the rubber meets the road in 2023."

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is an article I should send to my Trumper sister, explaining to her that the woman who wrote it is a card-carrying conservative. She worked and shilled for Ted Cruz and Jim DeMint (can't get much more GQP than those two).

Fox knew the truth but lied every night. The intellectual dishonesty is staggering but it took millions of people like my sister into dark fantasy places.

DropFox

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 118th Congress is the Least Productive Congress in Decades

Since Republicans took back the House of Representatives after the 2022 midterm elections, chaos has ruled the halls of Congress. In this current Congress (the 118th), only 27 bills have become law in 2023, out of 724 votes. So why the lack in productivity? It is simple: Republicans do not believe in governing.

During the 2022 midterm elections, Republicans hammered Democrats on inflation and rising gas prices. But in all those ads critiquing Biden and congressional Democrats, not one ad offered any solutions besides cutting spending. Of course, in all those ads, there was not one mention of Republicans voting for (and Pres. Trump signing) $3 trillion worth of spending in the previous Congress in 2020. And of course, there was not one mention of inflation being a global problem; not just something happening in the U.S. How convenient.

Republicans are comfortable criticizing those trying to govern while they remain on the sidelines. In 2009, when America was experiencing the Great Recession, Republicans repeatedly said "no" to anything Pres. Obama suggested. In fact, during Obama's inauguration, top Republican leaders (e.g., Kevin McCarthy, Paul Ryan, Jim DeMint) gathered at a steakhouse in Washington, D.C. to strategize on how they were going to fight Obama on everything, according to reporting from FRONTLINE on PBS.

*The documentary of the behind-the-scenes of the GOP's efforts to undermine Obama's presidency can be found below*

In the last Congress, when Democrats were in control, it was a different story. Democrats were able to pass the American Rescue Plan, CHIPS Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, the PACT Act, Respect for Marriage Act, and the Protecting Our Kids Act. Why the difference between the two parties? Because Democrats believe government can be a force for good and can help people, while Republicans believe government is intrinsically bad and should be as small as possible. The evidence and history is clear for voters going into 2024: either elect the party who will at least try to make things better, or vote for the anarchists.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The 2022 midterm elections offered many snapshots of the contemporary school wars,” Jessica Winter writes, about races across the country targeted by right-wing activists who have “turned public schools into the national stage of a manufactured culture war over critical race theory, L.G.B.T.Q. classroom materials, the sexual ‘grooming’ of children, and other vehicles of ‘woke leftist’ indoctrination.” In South Carolina, which is experiencing a major teacher shortage, two candidates for state superintendent—one with twenty-two years of teaching experience and a platform focussed on raising teacher pay, and another with no teaching experience, who leads a conservative think tank that advocates for “education freedom”—faced off on Tuesday. “Education freedom,” as it turns out, involves funnelling public funding into private schools and charter schools. “In short, the two people vying to run South Carolina’s public schools were an advocate for public schools, and . . . an opponent of public schools,” Winter writes. Maybe you can guess who won—handily. Winter examines several other races, and points out why rival factions in the school battles, increasingly polarized and infused with vitriol, should actually be working toward similar goals.

—Jessie Li, newsletter editor

The 2022 midterm elections offered many snapshots of the contemporary school wars, but one might start with the race for Superintendent of Education in South Carolina, a state that languishes near the bottom of national education rankings and that’s suffering from a major teacher shortage. Lisa Ellis, the Democratic candidate, has twenty-two years of teaching experience and is the founder of a nonprofit organization that focusses on raising teacher pay, lowering classroom sizes, and increasing mental-health resources in schools. Her Republican opponent, Ellen Weaver, who has no teaching experience, is the leader of a conservative think tank that advocates for “education freedom” in the form of more public funding for charter schools, private-school vouchers, homeschooling, and micro-schools. “Choice is truly, as Condi Rice says, the great civil-rights issue of our time,” Weaver stated in a debate with Ellis last week. In the same debate, Ellis argued that South Carolina does not have a teacher shortage, per se; rather, it has an understandable lack of qualified teachers who are willing to work for low pay in overcrowded classrooms, in an increasingly divisive political environment—a dilemma that is depressingly familiar across the country. Ellis also stressed that South Carolina has fallen short of its own public-school-funding formula since 2008, leaving schools billions of dollars in the hole. Weaver countered that the state could easily persuade non-teachers to teach, so long as they had some relevant “subject-matter expertise,” and warned against “throwing money at problems.” The salary floor for a public-school teacher in South Carolina is forty thousand dollars.

In short, the two people vying to run South Carolina’s public schools were an advocate for public schools, and—in her policy positions, if not in her overt messaging—an opponent of public schools. The latter won, and it wasn’t even close: as of this writing, Weaver has fifty-five per cent of the vote to Ellis’s forty-three. Weaver didn’t win on her own, of course—her supporters included Cleta Mitchell, the conservative activist and attorney who aided Donald Trump in his attempt to overthrow the 2020 election results; the founding chairman of Palmetto Promise, Jim DeMint, a former South Carolina senator who once opined that gay people and single mothers should not be permitted to teach in public schools; and Jeff Yass, a powerful donator to education PACs—at least one of which has funnelled money to Weaver’s campaign—and the richest man in Pennsylvania. (Yass, as ProPublica has reported, is also “a longtime financial patron” of a Pennsylvania state senator, Anthony Williams, who helped create “a pair of tax credits that allow companies to slash their state tax bills if they give money to private and charter schools.”)

Weaver borrowed the sloganeering and buzzwords of right-wing activist groups, such as the 1776 Project and Moms for Liberty—which, as my colleague Paige Williams recently reported, have turned public schools into the national stage of a manufactured culture war over critical race theory (C.R.T.), L.G.B.T.Q. classroom materials, the sexual “grooming” of children, and other vehicles of “woke leftist” indoctrination, as well as lingering resentment over COVID-19 lockdowns. During the debate, Weaver railed against C.R.T. and the “pornography” supposedly proliferating in schools, and associated Ellis with a “far-left, union-driven agenda.” (Incidentally, South Carolina’s public employees are prohibited from engaging in collective bargaining.) “They believe in pronoun politics. They believe parents are domestic terrorists, much like Merrick Garland,” Weaver said. (Weaver may have been referring to an incident in May, 2021, when Ellis’s nonprofit cancelled a protest after it “received harassing and threatening messages from groups with extreme views about masking,” including death threats.) “These are people,” Weaver went on, “who are out of touch with the mainstream of South Carolina values, and these are the people who my opponent calls friends.” Ellis maintained that those who profess to be hunting down proponents of C.R.T. in schools are “chasing ghosts.”

The ghost chasers bagged plenty of votes on Tuesday. A clown-car school-board race in Charleston, South Carolina, ended with five out of nine seats going to Moms for Liberty-backed candidates. Governor Ron DeSantis—the maestro of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” legislation and a home-state hero to Moms for Liberty—endorsed six school-board candidates, all of whom won their races; Moms for Liberty endorsed a total of twelve in Florida, winning nine. In Texas, ten out of fifteen spots on the state school board appeared to be going to Republicans, including three seats in which G.O.P. incumbents either lost or dropped out of their primary when facing opponents who took a harder line against C.R.T.

Another C.R.T.-haunted race, for education superintendent in Arizona, was as striking in its bizarre contrasts as the one in South Carolina. (As of this writing, the outcome is still a tossup.) The Republican challenger, a seventy-seven-year-old named Tom Horne, was banned for life by the S.E.C. in a past career as an investor; violated campaign-finance laws when he was the state’s attorney general; and was cited half a dozen times for speeding, including in a school zone, during a previous stint as education superintendent—a busy time when he also tried to outlaw bilingual education in public schools and to eliminate the Mexican American studies program in the Tucson Unified School District. His big thing now is—wait for it—banning critical race theory in the classroom. He also wants a greater law-enforcement presence in Arizona’s schools, because, as he has said, “the police are what make civilization possible.” Horne’s opponent is the Democratic incumbent, a thirty-six-year-old speech-language therapist and onetime preschool teacher named Kathy Hoffman who wants to—wait for it!—raise school budgets and teacher salaries, and lower class sizes. (The signature achievement of her first term as superintendent was to lower the counsellor-to-student ratio in public schools by twenty per cent.) Hoffman has a baby daughter and took her oath of office in 2019 on a copy of “Too Many Moose!,” one of her students’ favorite books. It’s as if Miss Binney from “Ramona the Pest” were running against Spiro Agnew.

The precise logical relation between the conservative-libertarian axis of billionaires who wish to privatize public education—notably among them Betsy DeVos, who was Secretary of Education under Trump—and the rank-and-file right-wing moms who back “Don’t Say Gay” is as yet unclear. For the moment, at least, their desires match—as Tuesday night’s election results have demonstrated—and nowhere is their bond stronger than in their shared antipathy for teachers’ unions, even in states where much of the meaningful work that unions do has been outlawed. On the eve of Election Day, one of Moms for Liberty’s founders, Tina Descovich, tweeted, “Teachers unions do not care about kids. Period.” The vision of “educational freedom” espoused by Ellen Weaver and her ideological comrades is one in which teachers are servants of parents and public money pours into private pockets, where any space can be a school and anybody can lead a classroom, and where whatever compact remains between parents and teachers—whatever sense of a community collaborating in a public good—dissolves.

The tragedy of the post-pandemic schools crisis, crystallized in Descovich’s tweet and in many of Tuesday’s election results, lies in how it has heightened the adversarial relationship between two groups whose interests should be closely aligned. (Or, indeed, one and the same: many teachers are parents.) As beleaguered as they are, most public-school systems are not yet splintering along DeVosian lines into a privatized mix of living-room salons and strip-mall micro-schools. Until then, public-school parents will continue to hand their children off to public employees in a public building for six hours per day, or eight, or nine. A degree of trust in these educators’ qualifications, their good faith, and even their state of mind is nonnegotiable. Poor working conditions for teachers are necessarily synonymous with poor learning conditions for students; overcrowded, under-ventilated classrooms are at once a political issue, a labor-rights issue, and a children’s-rights issue. Something the members of Moms for Liberty say a lot is “We don’t co-parent with the government.” Don’t we, though? ♦

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Advice for Seeking a New Job on the Hill

There are more than 10,000 employees working for Congress on Capitol Hill and elsewhere as aides to individual senators, representatives and committees. For anybody interested in public service, politics and government, being “on the Hill” can be literally nirvana.

Bret Bernhardt, former chief of staff for senators Don Nickles and Jim DeMint.

So what if you are looking for your first job on the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jim DeMint, the former U.S. senator from South Carolina, serves as the group’s top executive.Credit...Brendan Hoffman for The New York Times

0 notes

Text

Tim Scott Endorses Trump With Great Enthusiasm at NH Rally, Nikki Haley's Face Says It All

Folks were lining up early in the below freezing, New England winter weather for the Trump campaign rally in New Hampshire, where Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) was scheduled to make an endorsement of Trump on Friday night.

That's real dedication, to come out when it's 18 degrees out.

The announcement of the endorsement on Friday surprised former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, if this look from her is any indication. She seemed not quite willing to accept it, but her face says it all. She appointed Scott when he first came in as a replacement for Sen. Jim DeMint in 2012, so that would have to be a blow to her. Scott was a representative then.

READ MORE: Tim Scott Set to Snub Fellow South Carolinian Nikki Haley, Endorse Donald Trump

But Scoff was enthused for Trump ahead of the event.

Then when he was finally there, Trump was loving it and he wore a big smile over Scott's energy. Sen. Scott only spoke for a few minutes, but he certainly brought the fervor.

Scott had the campaign cadence going in full swing, saying Trump would deal with crime, lower taxes (again), and end our having to be "sick and tired" of being "sick and tired."

He said we needed a president whom our foreign adversaries are afraid of and whom our allies respect, and a president who sees us as one American family. He joked that was why he came to the very warm state of New Hampshire to endorse "the next president of the United States" -- Donald Trump.

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu wasn't a happy camper about Scott's endorsement. He said:

Tim Scott wouldn't have a job without Nikki Haley. Nobody cares what Tim Scott thinks. If they did, he actually wouldn't have been driven out of this race three months ago.

Sununu previously said no one cared about Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) coming out with a "Never Nikki" website and lobbying against Haley. But it sure looks like people are caring, when you have more olks like Scott moving to Trump.

Related:

Rand Paul Unleashed on Nikki Haley, Sununu Jumps to Her Defense, but Response Doesn't Bode Well for Her

1 note

·

View note

Text

How the republican party is currently shaping politics for generations to come with or without the democrats involvement.

It is important to note I am a democrat in practice but personally not a big fan of either party

The main reason the political system is the way it is currently is can be brought down to two events, the first election of Barack Obama, after the election the republican party shifted from a party with its own ideas and values to a party that will fight democrats on every issue, they shifted to opposing every view the democratic party had✝.

The other big event was the obvious one, the election of former president Donald John Trump, now the really interesting thing is that in a flash point not so far from our own our dear Trump was a democrat, he talked about running as a democrat twice and a republican once before his winning run in 2016, this really shows the core of Trump, he Isn't at heart a traditional republican, he doesn't truly belong to either party, he conformed to the views of his party to run and then was stuck with those views in order to appeal to his base, however it is important to note just how much he has fractured the party during his run in office, there are currently two 'brands' of republicans currently, the old school, Mitch McConnell, Mike Pence (although he is on the out and out) and arguable Chris Christie, this is contrasted against the new MAGA brand of republicans (alternatively the GQP), think Ron Desantis, Margarie Tailor Green, Lauren Boebert, Mat Gates, this divide in the republican party undeniably weakens the power of the republican party.

this leads to the situation we have today, a republican party that has more seats than the democrat party (I know its not functionally true but still) but has significantly less power than they should because of how divided they are.

this WILL lead to a not only a major shift in the face of the republican party, and due to the way the two parties interface also a massive shift in the democratic party towards centrism, or more accurately the public view of what centrism is has been progressively shifted towards the democrats current views, meanwhile the republican party is becoming more extreme leading to a massive shift towards democratic popularity.

For example Columbia district 3, Boebert was up against a pretty much no name democrat, this was a very safe seat with a large majority, but in the last election in an election of 330000 votes, Boebert only won by 600, not 6000, 600, if a couple of neighbourhoods had changed her mind she wouldn't be in.

this is down to the way media is shaping the political landscape and the polarisation of the republican voters, the important thing to note is the alternative ways the parties are appealing to voters, the democrats have been coming into the 'mainstream' and centrist news sources* and swaying their causes wildly to the left, infecting them with partisan comedy shows** that appeal to the masses.

instead of competing with them on their own terms the republicans have taken their voters and supporters and segregated them from mainstream news through vessels such as the classic example of fox news through which they can be told an unregulated set of 'alternative facts' and be led to further extremism such as QAnon, which particularly the MAGA or GQP are weaponising to fuel their party beliefs and to motivate their followers to do what they want (eg, turn out to vote, commit an insurrection, buy their lumpy pillows)

the difference in outcomes being that democrats have a lot of unmotivated voters however the republican base is highly motivated,

both parties are willing to compromise on their morals and beliefs it is just that the republicans have the strength and mental willpower to get in with much more unsavoury bedfellows and get the deed done.

✝ see the republican steakhouse dinner organised by Frank Luntz involving the higher ups at the GOP including Jim DeMint, John Kyl, Tom Coburn, Erik Cantor, Kevin McKarthy, Paul Ryan and 2-3 others.

*it is important to note that most 'leftist' NEWS programs are rather centrist and the democrats have very little influence there, however just appearing on those shows and not absolutely flubbing the interview leaves a positive impression of the candidate on most viewers.

**Yes Gutfield exists but the problem is that democrats take comedians and makes them tell the news whereas republicans take news presenters and make them tell jokes so it doesn't work as well.

0 notes

Text

班农好友或执掌美国全球媒体署,“美国之音”变特朗普之音?

美国参议院外交委员会本周四(5月14日)将就总统特朗普提名的美国全球媒体总署(USAGM)负责人举行投票表决。民主党担心如果提名获得批准,将使一系列美国政府资助的媒体变成特朗普的宣传工具。

美国全球媒体总署负责监管所有由政府资助的国际新闻机构,包括众多创始于冷战时期的美国对外宣传机构,例如美国之音(VOA)、自由亚洲电台(Radio Free Asia)、自由欧洲电台(Radio Free Europe),以及向古巴广播的马蒂广播电视台(Radio Marti)等。

特朗普此前提名保守派电影制片人迈克尔•帕克(Michael Pack)担任这一政府机构的负责人。据美联社5月13日报道,预计周四共和党控制的参议院将推进这一题名。

据报道,帕克的提名在参议院已被搁置了近两年,这引起了特朗普的强烈不满。4月15日,特朗普威胁将动用总统权力让国会休会,进行“休会任命”。

特朗普还对全球媒体总署下属的美国之音提出尖锐批评,称其行为“令人作呕”。此前,白宫在4月9日的简报中曾痛批美国之音每年花费美国纳税人2亿美元,却帮助中国和伊朗做宣传。

不过,美国之音遭到白宫批评的关于武汉解除封锁的报道实际上是美联社的一篇报道,美国之音只是转发而已。

特朗普一直试图取得全球媒体署和美国之音更多的控制权。在其刚上任不久,美国之音曾质疑白宫发言人夸大出席就职典礼的人数,特朗普随后向美国之音在华盛顿的新闻编辑室派了两名官员负责评审。

美联社报道指出,民主党人担心特朗普提名出任全球媒体总署负责人的迈克尔•帕克,可能会将这一政府资助的机构变成特朗普的宣传机器。

眼下特朗普政府在抗击疫情中的表现遭到广泛批评,美联社指出,随着2020年总统大选临近,在疫情问题上甩锅中国转移国内批评已经成为特朗普政府的“试金石”。

尽管去年9月帕克在参议院出席听证会时曾经承诺,不会让特朗普的政治偏见影响美国之音的独立性。但是最近围绕全球媒体署和美国之音的争吵,加剧了外界的担忧。

据报道,这一争吵令许多密切关注这个问题的人士感到沮丧,也包括那些认为全球媒体署和美国之音需要改革的人士。报道称,全球媒体署管理规则的变化意味着,该机构下一任负责人可以绕过董事会作出人事和政策决策。

《纽约时报》上周报道,早在白宫公开攻击美国之音之前,该机构高层管理人员,前总统奥巴马任命的人员以及传统媒体背景的人员都预计,如果帕克提名获得确认,他们的工作将会不保。

而《华盛顿时报》不久前报道,帕克正计划对美国各家电台进行“大清理”,包括撤销现任美国之音台长阿曼达•贝内特(Amanda Bennet)的职务。贝内特4月10日在推特上反驳了白宫前一天对美国之音的指责。

帕克是一名保守派的制片人,与特朗普的前白宫首席战略师史蒂夫•班农(Stephen Bannon)是好友,二人曾经合作拍摄过制作过有关检视伊拉克战争与核能的纪录片。班农一直对美国之音持批评态度,2018年他曾称美国之音是“腐烂透顶的鱼”,“完全被‘深层国家’所控制。”

美联社报道,帕克出任全球媒体总署的提名得到了一群强大的保守派活动人士和机构的支持,包括保守派智库传统基金会,以及曾担任该智库总裁的前共和党参议员吉姆•德敏特( Jim DeMint )。

预计帕克的提名将在共和党的支持下获得通过。据《纽约时报》报道,为了让帕克的提名尽快获得确认,特朗普向参议院共和党施加了很大的压力。知情者称,特朗普亲自打电话给参议院多数党领袖麦康奈尔,要求他加快提名确认过程。在参议院上周正式复会之后,麦康奈尔随即将其提上了日程,表示将“推进搁置太久的合格提名”。

0 notes

Text

Inside the Trump world-organized retreat to plot out Biden oversight

Among those who briefed the congressional aides was a former Trump administration official, an energy lobbyist and a reporter from Epoch Times, a nonprofit media company tied to the Falun Gong Chinese spiritual community and known for its conspiratorial, pro-Trump views.

Founded in 2017 and chaired by former Sen. Jim DeMint (R-S.C.), CPI is a relative newcomer in the Washington conservative…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

班农好友或执掌美国全球媒体署,“美国之音”变特朗普之音?

美国参议院外交委员会本周四(5月14日)将就总统特朗普提名的美国全球媒体总署(USAGM)负责人举行投票表决。民主党担心如果提名获得批准,将使一系列美国政府资助的媒体变成特朗普的宣传工具。

美国全球媒体总署负责监管所有由政府资助的国际新闻机构,包括众多创始于冷战时期的美国对外宣传机构,例如美国之音(VOA)、自由亚洲电台(Radio Free Asia)、自由欧洲电台(Radio Free Europe),以及向古巴广播的马蒂广播电视台(Radio Marti)等。

特朗普此前提名保守派电影制片人迈克尔•帕克(Michael Pack)担任这一政府机构的负责人。据美联社5月13日报道,预计周四共和党控制的参议院将推进这一题名。

据报道,帕克的提名在参议院已被搁置了近两年,这引起了特朗普的强烈不满。4月15日,特朗普威胁将动用总统权力让国会休会,进行“休会任命”。

特朗普还对全球媒体总署下属的美国之音提出尖锐批评,称其行为“令人作呕”。此前,白宫在4月9日的简报中曾痛批美国之音每年花费美国纳税人2亿美元,却帮助中国和伊朗做宣传。

不过,美国之音遭到白宫批评的关于武汉解除封锁的报道实际上是美联社的一篇报道,美国之音只是转发而已。

特朗普一直试图取得全球媒体署和美国之音更多的控制权。在其刚上任不久,美国之音曾质疑白宫发言人夸大出席就职典礼的人数,特朗普随后向美国之音在华盛顿的新闻编辑室派了两名官员负责评审。

美联社报道指出,民主党人担心特朗普提名出任全球媒体总署负责人的迈克尔•帕克,可能会将这一政府资助的机构变成特朗普的宣传机器。

眼下特朗普政府在抗击疫情中的表现遭到广泛批评,美联社指出,随着2020年总统大选临近,在疫情问题上甩锅中国转移国内批评已经成为特朗普政府的“试金石”。

尽管去年9月帕克在参议院出席听证会时曾经承诺,不会让特朗普的政治偏见影响美国之音的独立性。但是最近围绕全球媒体署和美国之音的争吵,加剧了外界的担忧。

据报道,这一争吵令许多密切关注这个问题的人士感到沮丧,也包括那些认为全球媒体署和美国之音需要改革的人士。报道称,全球媒体署管理规则的变化意味着,该机构下一任负责人可以绕过董事会作出人事和政策决策。

《纽约时报》上周报道,早在白宫公开攻击美国之音之前,该机构高层管理人员,前总统奥巴马任命的人员以及传统媒体背景的人员都预计,如果帕克提名获得确认,他们的工作将会不保。

而《华盛顿时报》不久前报道,帕克正计划对美国各家电台进行“大清理”,包括撤销现任美国之音台长阿曼达•贝内特(Amanda Bennet)的职务。贝内特4月10日在推特上反驳了白宫前一天对美国之音的指责。

帕克是一名保守派的制片人,与特朗普的前白宫首席战略师史蒂夫•班农(Stephen Bannon)是好友,二人曾经合作拍摄过制作过有关检视伊拉克战争与核能的纪录片。班农一直对美国之音持批评态度,2018年他曾称美国之音是“腐烂透顶的鱼”,“完全被‘深层国家’所控制。”

美联社报道,帕克出任全球媒体总署的提名得到了一群强大的保守派活动人士和机构的支持,包括保守派智库传统基金会,以及曾担任该智库总裁的前共和党参议员吉姆•德敏特( Jim DeMint )。

预计帕克的提名将在共和党的支持下获得通过。据《纽约时报》报道,为了让帕克的提名尽快获得确认,特朗普向参议院共和党施加了很大的压力。知情者称,特朗普亲自打电话给参议院多数党领袖麦康奈尔,要求他加快提名确认过程。在参议院上周正式复会之后,麦康奈尔随即将其提上了日程,表示将“推进搁置太久的合格提名”。

0 notes

Text

On “The Family” or “The Fellowship”

There has recently been a post on WIOTM discussing the Fellowship or the Family (not to be confused with the Family International, or the Children of God), linking this organization to both the Moral Re-Armament Movement and the Moonies. Understanding this organization has helped me understand the UC’s role in politics, too, especially from the 80s-early 2000s. If you haven’t seen it yet, there’s a Netflix documentary on the Family, but it still holds back from giving much of its history and shying away from its covert political activities.

This excerpt from 'C Street: The Fundamentalist Threat to American Democracy' should be read by those who want to understand parapolitics and the Moonies, and how religion has been creatively weaponized by the United States gov’t. I bolded certain parts of the section of the book myself.

Pres. Biden at the Fellowship-run National Prayer Breakfast

EXCERPT:

THE CONFESSIONS

“As much as I did talk about going to the Appalachian Trail ... that isn’t where I ended up.”

— South Carolina governor Mark Sanford, at the June 24, 2009, press conference at which he confessed to cheating on his wife.

In 2008 I published a book called The Family, which took as its main subject a religious movement known to some as the Fellowship and to others as the Family and to most only through one of the many nonprofit entities created to express the movement’s peculiar approach to religion, politics, and power. One of these entities is the C Street Center Inc., in Washington, DC, or, simply, C Street, made infamous in the summer of 2009 by the actions of three Family associates: a senator, a governor, and a congressman, each with his own special C Street connection.

The senator lived there; the governor sought answers there; and the congressman’s wife says he rendezvoused with his mistress in his bedroom at the three-story redbrick town house on Capitol Hill, maintained by the Family for a singular goal, in the words of one Family leader: to “assist [congressmen] in better understandings of the teachings of Christ, and applying it to their jobs.”

Among the men thus assisted by the Family have been Sen. Tom Coburn and Sen. Jim Inhofe, Oklahoma Republicans racing each other to the far right of the political spectrum (Coburn has proposed the death penalty for abortion providers; Inhofe, who was a defender of the Abu Ghraib torturers, hosts regular foreign policy meetings at C Street); Sen. Jim DeMint of South Carolina, who insists that the Bible teaches we cannot serve both God and government; and Sen. Sam Brownback (R- KS), who says that through meetings of his Family “cell” of like- minded politicians he receives divine instruction on subjects as varied as sex, oil, and Islam. There’s also Sen. John Thune (R- SD), Sen. Chuck Grassley (R- IA), and Sen. Mike Enzi (R- WY); Rep. Frank Wolf (R- VA), Rep. Zach Wamp (R- TN), and Rep. Joe Pitts (R- PA). And Democrats, too: among them are Sen. Bill Nelson of Florida; North Carolina’s Ten Commandments crusader, Rep. Mike McIntyre; its newest Blue Dog, Rep. Heath Shuler; and Michigan’s Rep. Bart Stupak. In 2009 Stupak joined with Rep. Pitts to hold health care reform hostage to what Family leaders, pledging their support for Pitts early in his career, called “God’s leadership” in the long war against abortion.

Buried in the 592 boxes of documents dumped by the Family at the Billy Graham Center Archives in Wheaton, Illinois, are five decades’ worth of correspondence between members equally illustrious in their day: segregationist Dixiecrats and Southern Republican converts Sen. Absalom Willis Robertson (Pat Robertson’s father) and Sen. Strom Thurmond; a Yankee Klansman named Ralph Brewster and a blue- blooded fascist sympathizer named Merwin Hart; a parade of generals, oilmen, bankers, missile manufacturers; little big men of the provinces with fast food fortunes or chains of Piggly Wiggly supermarkets or gravel quarry empires. There was even the occasional liberal — Sen. Mark Hatfield, Republican of Oregon, and Sen. Harold Hughes, Democrat of Iowa — men of good faith and bad judgment who lent their names to the causes of the Family’s “brothers” overseas, the Indonesian genocidaire Suharto (Hatfield), the Filipino strongman Ferdinand Marcos (Hughes).

“Christ ministered to a few and did not set out to minister to large throngs of people,” says a supporter. The Family differs from more conventional fundamentalist groups in its preference for those whom it calls “key men” over the multitude. “We simply call ourselves the fellowship or a family of friends,” declares a document titled “Eight Core Aspects of the vision and methods,” distributed to members at the 2010 National Prayer Breakfast, the movement’s only public event. One of the Eight Core Aspects is the movement’s interpretation of Acts 9: 15 — “This man is my chosen instrument to take my name ... before the Gentiles and their kings” (emphasis theirs). The Family’s unorthodox reading of this verse is that it is an injunction to work not through public revivals but through private relationships with “ ‘the king’ —or other leaders of our world — who hold enormous influence — for better or worse — over vast numbers of people.” The Family sees itself as a ministry for the benefit of the poor, by way of the powerful. The best way to help the weak, it teaches, is to help the strong.

In 2008 and 2009, the Family did so by helping Sen. John Ensign (R- NV), Gov. Mark Sanford (R- SC), and former representative Chip Pickering (R- MS) cover up extramarital affairs, and in Ensign’s case secret payments. Not to avoid embarrassment for the Family, an organization that until 2009 denied its own existence, but because the Family believes that its members are placed in power by God; that they are his “new chosen”; that the senator, the governor, and the congressman were “tools” with which to advance his kingdom, an ambition so worthy that beside it all personal failings pale.

On June 16, 2009, Sen. Ensign flew home to Las Vegas to confess his affair. Ensign, fourth- ranking Republican and a man with Iowa and Pennsylvania Avenue on his mind, had made a career of going against the grain of his hometown. He was a moral scold who’d promoted himself as a Promise Keeper — a member of the conservative men’s ministry — and a family values man. He’d been a hound once, according to friends, but he’d come to Christ before he came to politics; for Ensign, the two passions were intertwined. He didn’t just go to church, he lived in one, the Family’s house at 133 C Street, SE, registered as a church for tax purposes.

I’d met Ensign there once, when I was writing an earlier book on unusual religious communities around the country. I’d seen some strange things: a Pentecostal exorcism in North Carolina; a massive outdoor Pagan dance party in honor of “the Horned One” in rural Kansas; a “cowboy church” in Texas featuring a cross made of horseshoes and, in lieu of a picture of Jesus, a lovely portrait of a seriously horned Texas Longhorn steer.

But C Street was in its own category, simultaneously banal — a prayer meeting of congressmen in which they insisted on calling God “Coach” — and more unsettling than anything I’d witnessed. Doug Coe, the “first brother” of the Family since 1969, used to say that Jesus was not a sissy. That disdain for weakness infuses the movement’s theology so completely, so naturally, that it comes across as almost amiable. “I’ve seen pictures of the young men in the Red Guard,” he says in a videotaped sermon, a tall man in a rumpled suit, spreading out his hands like he’s setting up a joke. “They would bring in this young man’s mother ... he would take an axe and cut her head off.” Coe makes a chopping motion. That, he says, is dedication to a cause. But there’s nothing grim about his presentation; he sounds like he’s inviting you to join a team or a fund-raiser. And he is. “A covenant! A pledge!” he exclaims, setting up the punch line. “That’s what Jesus said.” Such is the C Street style, the most violent metaphors imaginable deployed as maxims for everyday living, from the prayer calendar on the wall that called on the house’s congressional tenants to devote a portion of each morning to spiritual war (combat by prayer) against “demonic strongholds” such as Buddhism and Hinduism, to Coe’s routine invocation of history’s worst villains as models for the muscle he’d rather see applied on Christ’s behalf. The first time I met Coe, he was in the midst of a spiritual mentoring session in which he cited “Hitler, Lenin, Ho Chi Minh [and] bin Laden” as models with which to understand the “total Jesus” worshipped by the Family. He sipped hot cocoa while he lectured.

Ensign seemed to fall on the banal end of that spectrum. He missed the prayer meeting, bouncing into the foyer in red jogging shorts and a white T- shirt that made his tan — the most impressive tan in the Technicolor portrait gallery of golf-happy, twenty-first-century political America — glow beneath his equally striking silver hair. Ensign’s hair, prematurely gray, is his most senatorial feature; it possesses a gravitas all its own. The man beneath it, though, square-jawed and thick-browed, is something of a giggler. Jogging in place, grinning, bobbing his head back and forth, he boasted to a young female aide who’d been sent to fetch him about the time he’d clocked on his run. “That’s great!” she said, then asked him what kind of time he could make showering and getting ready for work. Up popped Ensign’s arched black brows: a challenge! “I’m all about setting records today!” he said.

And away he went. When I wrote The Family, I devoted only a sentence to him, describing him as a “conservative casino heir elected to the Senate from Nevada, a brightly tanned, hapless figure who uses his Family connections to graft holiness to his gambling- fortune name.” After his press conference, a magazine editor, noting Ensign’s Washington address and recalling my book, asked me if I wanted to write something about Ensign’s apparent hypocrisy. I didn’t. The senator’s sins were his own.

Next up was Mark Sanford, the weather- beaten governor of South Carolina, his tan the result of days spent in the woods, hunting, or on his tractor, planting. He was famous for his frugality. As a congressman, he slept on a futon rolled out across his office rather than coughing up rent, and as governor he turned down $700 million in federal stimulus money because he feared it would lead to “a thing called slavery.” In 1995, when Ensign and Sanford were at the vanguard of the right- wing revolution, Ensign quietly continued business as usual, collecting $450,000 from political action committees, more than any other freshman. Mark Sanford refused to take a dime. By 2009, even more than Ensign Sanford was being spoken of as presidential material for the GOP, fabric to be cut, folded, and sewn.

So, when on June 18, 2009, Sanford disappeared, some assumed it was for a good or maybe even a noble reason. For days, there were whispers about where the governor had gone — gone being the operative word, because nobody knew where the governor was. Not in the governor’s mansion in Columbia, not in the airy beach house on Sullivan’s Island he shared with his wife, Jenny Sanford, and their four boys, not at Coosaw, the semi- feral, falling- down plantation along the Combahee River that had originally brought the Sanford clan, Floridians, to South Carolina. Calls to his wife, the state’s elegantly beautiful First Lady, a gentlewoman, in the antique parlance of the state’s finest matrons, led reporters to believe the governor was thinking, working on a book about the meaning of conservatism. Calls to his staff led seekers to the woods: to the Appalachian Trail, to which the governor was said to have taken in contemplation.

Contemplation of what? Hopes rose, résumés rustled, ambitions flared, as Sanford’s circle imagined the governor emerging from the wilderness as a new kind of contender. They didn’t see the truth coming. “Mark Sanford literally likes to go his own way,” gushed GOP consultant Mark McKinnon, whose clients have included George W. Bush and John McCain. “For this act alone, we’re going to move Sanford up at least a notch on our Top 10 GOP contenders for 2012.” In the days ahead he’d become a laughingstock: a symbol of all that is pathetic about politics, men, middle age, even romance itself at the tired end of a decade celebrated by no one. But before that, while he was still gone, so long as nobody knew where he was, when the governor for a moment occupied a space in the realm between the possibility of tragedy (was he silent because his broken body lay at the bottom of a gully?) and the transcendent (would he walk out of the woods with the wisdom of one who knows how to quiet the world’s noise?), he was almost a folk hero.

His supporters — the true believers who loved his Roman nose and his leathery skin and his wry smile, and the Washington slicks who would sell these features as the face of a modern-day Cincinnatus, a reluctant philosopher-king for the common man — asked themselves if this strange departure would herald his arrival. Would the governor return from the wilderness to announce a higher aspiration?

Yes, in a sense: love. On June 24, after a reporter for the Columbia State tracked him down in a Georgia airport and discovered he’d returned from Argentina, Sanford called a press conference at which he mused on his genuine affection for the Appalachian Trail, then pledged to “lay out that larger story” — the story of where he’d been the previous week. “Given the immediacy of y’all’s wanting to visit,” he said, he was forced to intrude private concerns into a public meeting. He began with apologies to Jenny and his four boys, “jewels and blessings,” his staff, and an old friend — the memory of whose early support brought the governor close to tears. “I let them down by creating a fiction with regard to where I was going,” he said. He had been on an “adventure trip,” indeed, but not on the Appalachian Trail. He rubbed his forehead, his eyes glanced off into nowhere, his voice wobbled. “I’m here,” he continued, still deferring any concrete explanation of why he actually was there, “because if you were to look at God’s laws, they’re in every instance designed to protect people from themselves.” He warmed to the subject of religion, firmer ground, he knew, for the narrative of public confession. “The biggest self of self is indeed self.”

The answer to that riddle was a woman. The “biggest self of self” for Sanford was love; he’d fallen into it, and he wanted us to forgive him.

To that point, I’d been interested only in the convoluted candor with which he was testifying. It was some good church, tension building, a parade of emotions not often on display in political life. I admired him for it. Then came the kicker. In answer to a question about how long his family had known (five months), Sanford paused, as if lost in recollection. Then: “I’ve been to a lot of — as part of what we called C Street when I was in Washington. It was a, believe it or not, a Christian Bible study — some folks who asked members of Congress hard questions that I think were very, very important. And I’ve been working with them.”

Another spiritual adviser, Warren “Cubby” Culbertson, was at the press conference. Every month, Cubby and two seminary professors invited fifteen well- connected men for a meeting at a downtown office where Cubby, a wealthy entrepreneur, would train them in the use of “spiritual weaponry,” with distinctly political implications. “Never underestimate the influence the ungodly have upon the godly,” he warned. “The ungodly want to unlord the Lord, but they must first unlord the law.” It was a ministry for men who had already achieved financial success and yet wanted more — meaning greater influence. The “up and out,” as the Family calls such people. “The ostrich has wings,” Cubby taught, “but cannot fly.” By which he meant: “The almost saved are totally damned.” No half measures. The men Cubby brought to God were instructed to become the “most holy,” to “enter God’s playing field,” to take God’s “litmus tests.” Ask yourself: Do I keep my eye on “the enemies known as the world”? “The children of the devil are obvious,” Cubby advised, citing 1 John 3:9; avoid them or become an “eternal inhabitant of Sodom.”

At the press conference, you could almost see Sanford weighing his options, trying to hold on to his ambition, lamenting the loss of the woman he’d already described to Jenny as his “heart connection.” Then he made his choice: C Street. “A spiritual giant,” Sanford said of Cubby, who was looking on from the back of the room, and finally tears began to fall.

* * *

I was stunned. One of the first rules of C Street is that you don’t talk about C Street. “We sort of don’t talk to the press about the house,” C Streeter Bart Stupak, a conservative Democrat, had told a reporter back in 2002. Another C

Streeter, Zach Wamp, spoke out against transparency in the wake of the Ensign scandal. “The C Street residents have all agreed they won’t talk about their private living arrangements, Wamp said, and he [Wamp] intends to honor that pact,” reported the Knoxville News- Sentinel , after scandal forced the press to pay attention.

“I hate it that John Ensign lives in the house and this happened because it opens up all of these kinds of questions,” Wamp told the paper. “I’m not going to be the guy who goes out and talks.”

From the Family’s point of view, C Street’s code of secrecy is not a conspiracy but a matter of simple efficiency. “The more invisible you can make your organization,” Doug Coe observes, “the more influence it will have.” True enough; that’s why we have lobbying and disclosure laws. It’s also part of why we have the Fourth Estate, the press, to hold the powerful accountable. If the press can’t comfort the afflicted, as the old saying goes — and even as a onetime employee of a freebie paper used primarily by homeless men for warmth in the winter, I doubt that it can — it may, on occasion, afflict the comfortable.

But most reporters have never shown much interest in C Street or the organization behind it. The exceptions are remarkable for the scrutiny that didn’t follow. Not in 1952, when the Washington Post noticed that the Secretary of Defense had granted four senators the use of a military plane for international Family meetings; questions were raised, then dropped. No questions at all followed the New Republic’s 1965 report on the Family’s only public event, the National Prayer Breakfast (then the Presidential Prayer Breakfast), an evangelical ritual of national devotion that politicians skipped at their peril. In 1975 Playboy published an exhaustively researched report on how the Family functioned as an off-the-books bank for its congressional members. Then, nothing.

Not even Watergate could goad the press into real action. The New York Times noted that President Ford had convened his old all- Republican congressional prayer group — organized by the Family — to consider Nixon’s pardon, but asked no questions about what criteria it would use. Time did a little better, identifying Doug Coe as the top man of what it described as “almost an underground network,” an “intricate web” of Christian activists in the capital, but left it at that. In December 1973, Dan Rather challenged his deputy press secretary to explain why Watergate conspirator Chuck Colson continued to make frequent visits to the White House he’d left in criminal disgrace. “Prayer,” came the answer. “Now we all know the way Washington works,” Rather replied. “People ingratiate themselves with people in positions of power, and at such things as, yes, a prayer breakfast, they do their business. Isn’t someone around here worried at least about the symbolism of this?” Apparently not; the questions that followed were bemused. Nobody seriously wondered why the soon-to-be- convicted Watergate conspirator, a man who had allegedly proposed firebombing the Brookings Institution, needed to worship in the White House. Not even a few years later, when Colson, never good at keeping his mouth shut, told the story of Doug Coe’s collaboration with the CEO of Raytheon, manufacturer of missiles, to bring Colson into the Family fold. “A veritable underground of Christ’s men all through government,” as Colson called the network that would vouch for his parole after only six months in prison.

Coe himself boasted of what the press couldn’t see, declaring that the single public event, the Prayer Breakfast, “is only one-tenth of one percent of the iceberg ... [and] doesn’t give the true picture of what is going on.” Ronald Reagan almost dared someone to ask questions in 1985, announcing at the Prayer Breakfast that he wished he could say more about the sponsor of the elite gathering. “But it’s working precisely because it’s private.” By the age of Reagan, much of the press had come to see that as a virtue. “Members of the media know,” said Reagan, “but they have, with great understanding and dignity, generally kept it quiet. I’ve had my moments with the press, but I commend them this day, for the way they’ve worked to maintain the integrity of this movement.” Time, for instance, ran a feature on the “Bible Beltway,” rife with factual errors and seeming to almost celebrate “the semisecret involvement of so many high-powered names.” There was Secretary of State James Baker and his wife, Susan; the Kemps; the Quayles; and a Democrat, Don Bonker of Washington, since departed from Congress to become a free trade lobbyist. The presence of Democrats as well as Republicans, the magazine proposed, proved there could be no politics involved.

The first serious report in decades came in 2002, when Lisa Getter, a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter for the Los Angeles Times, published a major front-page exposé in which she revealed that the Family dispatched congressmen as missionaries to carry the Gospel to Muslim leaders around the world — and did so with a “vow of silence.” The media response was — well, there was no response. Several months later, the Associated Press reported on C Street’s subsidized housing for the anointed, describing the Family as “a secretive religious organization.” Nobody followed up on that story, either. That spring, I published in Harper’s magazine an account of a month I’d spent living with the Family in Virginia. I included a C Street vignette, a spiritual counseling session between Doug Coe and Rep. Todd Tiahrt, a Kansas Republican. Tiahrt came seeking wisdom on how Christians could win the population “race” with “the Muslim” and left contemplating Coe’s advice to consider Christ through the historical lens of Hitler, Lenin, and Osama bin Laden. Like the other stories before it, mine was left to stand alone, giggled over and gossiped about by media colleagues but treated as a true tale of the quirks of the political class that demanded no further investigation.

Or, worse, it fell victim to the rule of reductio ad Hitlerum, the sensible Internet adage that holds that the first party in a debate to compare an opponent to Hitler loses. In 2004, a Democratic candidate for the northern Virginia congressional seat held by Republican Frank Wolf noted Wolf’s association with Coe. Coe’s Hitler talk wasn’t limited to the example of power I’d witnessed him offering Rep. Tiahrt at C Street, although it has to be said, immediately and emphatically, that Coe is not a neo-Nazi. He uses Hitler, his defenders declare, as a metaphor. For what? For Jesus. The lion and the lamb are too abstract for Coe. He asks his followers to imagine pure power, as modeled by Hitler and other totalitarians; then, he instructs, imagine that power used for Christ, for good instead of evil.

When the Virginia Democratic candidate pointed to these unorthodox teachings, the Washington Post would have none of it, editorializing against this low blow and dispatching a reporter to prove it untrue for good measure. He did so by asking the aggrieved parties and their friends if the accusations were true; they assured him they were not. Case closed — until 2008, when NBC aired videotape given to me by an evangelical critic of the Family’s “spiritual abuse,” as he put it, depicting Coe rattling on to a group of evangelical leaders about the fellowship model offered by “Hitler, Goebbels, and Himmler.” There was more: audio buried deep on the website of the Navigators, a fundamentalist ministry, of Coe going into greater detail on the depth of commitment he thought his disciples should learn from such men: “You say, hey, you know Jesus said, ‘You got to put him before mother- father- brother- sister’? Hitler, Lenin, Mao, that’s what they taught the kids. Mao even had the kids killing their own mother and father. But it wasn’t murder. It was for building the new nation. The new kingdom.”

None of this, not even the NBC News video, broke the story beyond a few isolated blips in the news cycle. There was no conspiracy of silence. Rather, all of these reports were lost in the black hole of conventional wisdom. A scoop, for most reporters, isn’t actually a new story; it’s a twist or a new variation on a story people already think they understand, a story that reassures the reader that his or her cynicism is justified and yet contained within the known realm of vice: stuffed in an envelope next to a wad of Ben Franklins or tucked into bed beside a stripper. The parameters for stories about religion in politics are even narrower: fundamentalism sells, but only if it’s low-class, the purview of sweaty Southern men in too-tight suits pounding pulpits and thumping Bibles. C Street — a distinguished address, an upscale clientele, an internationalist perspective — simply did not register.

Until, that is, sex entered the story. Suddenly, the media that had ignored C Street for years needed to know all about it. Or, rather, not all about it, not its implications for democracy and desire; interest was limited to the topic of hypocrisy, publicly pious Republicans, and their secret lovers. Ensign’s affair was at that early stage still mostly limited to his two-minute press conference and a few grubby, isolated details: that his best friend’s wife was the best friend of Ensign’s wife, for instance. Mark Sanford, on the other hand, offered both sex and schadenfreude, an exotic mistress and love letters exposed, a wife, Jenny Sanford, who refused to stand by her man, and a man who refused to stop talking about his lover. And then there was C Street, the mysterious address linked to both scandals.

I was the only reporter to have written from within its walls, and suddenly that mattered in a way it hadn’t before, when I’d been bleating on about the Family’s support for murderous regimes in Haiti and Indonesia and Somalia, machete militias and “kill lists” and rape rooms, all blessed by the Family’s faith and financed by its “leaders led by God” in Washington. Boring! Or, as one young radio producer put it, “What’s a Somalia?”

But consensual sex between adults? That could be news. Only by dispensing with the dead, though — “Let’s save Somalia for another time!” another producer suggested brightly — and kicking the heartbroken while they were down. That’s what Sanford was. The man had fallen in love, and everybody has done stupid things for love, and most of us, at one point or another, have done something awful. That’s not really news, it’s an Aesop’s fable. Evangelicals ritualize this truth with the declaration that we’re all sinners; secular folk speak of psychology’s contradictions. But such recognitions are reserved for private lives, and Mark Sanford’s self-destruction was public spectacle, served up for our satisfaction.

Shortly after the governor’s press conference, MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow invited me on her evening show. I’d spoken to Maddow several times during her radio days, and I knew she was one of the smartest hosts in broadcast journalism. But I was conflicted about discussing Sanford. Sanford was done. The question that remained was, Do we gloat over his hypocrisy? Or do we welcome him into the human race — where the heart wants what it wants and that’s not always a simple or good thing, even when it’s a true thing?

I don’t think I would have been able to do that in a five minute television interview, which is why I thank God for the sad intervention of Michael Jackson. I imagine Mark Sanford said much the same thing on June 25, the day the Sanford scandal started to crest, and also the day Michael Jackson died. Suddenly, one southern governor’s affair was very small news.

I was buying a new pair of shoes when I heard. When I’d received the invitation to be on the Maddow show, I was wearing flip- flops. That seemed too casual for a TV studio, and besides, I needed a new pair of shoes. I tried Shoe Mania, in Manhattan’s Union Square. The store was abuzz: He’s dead! Who? Michael Jackson! Michael Jackson is dead. I was stunned. In my grief, I bought a pair of shoes Michael might have liked, long, polished, and pointy, flashier than any I’d ever owned.

I walked out onto Broadway, where drivers had opened their windows and jacked up their radios, “Rock with You” mingling with the honk and roar of the city at rush hour. Some people didn’t hear it, some didn’t care, but sprinkled up and down the avenue there was immediate mourning. I saw an old woman crying and three middle-aged white men with beer guts goofing the moonwalk and girls who hadn’t been born yet in the days of “Billie Jean” gliding backward up Broadway, smooth as Michael’s falsetto. Here was another spectacle of self- destruction, but the public responded not with vicious glee, as to a sex scandal, as to so many of Jackson’s failings in the past, but with necessary delight; with the remembrance of transcendence; with the late recognition of something that had been lost long before. Over the radio and in the faltering and fluid dance steps of the mourners thumped the beat of pop democracy, Walt Whitman you could dance to, songs that mattered more to how we all imagined and dreamed ourselves than any of Michael’s scandals — much less those of a couple of Republican politicians bent on disowning their own desires. So why the hell was I going on TV to count the sins of the love-struck governor of South Carolina?

I wasn’t. I was barely a block away from the shoe store when a call came from MSNBC. I’d been bumped. “Thank you, Michael Jackson,” I thought. The King of Pop had saved my soul, prevented me from playing the part of a puritan, scolding Sanford for his confession when his real weakness was not his transgression — seedy, selfish, and human — but his retreat. He’d set out on the road to Damascus but had turned back too early. Instead of becoming an apostle of a love as free as his economic libertarianism, he’d fallen back on “God’s law.” And that was defined for him by C Street not as liberation but as the sort of freedom that isn’t free, that which protects us from ourselves, “this notion,” as he put it, “of what it is that I want.”

Unless, that is, what we want is power.

And then, King David drew me back to the story. Two days after Sanford’s public tears, he seemed back in control of himself. Opening a televised cabinet meeting, he spoke calmly of scripture, as if he were Cubby Culbertson himself, leading a spiritual counseling session. The topic was resignation: Sanford’s rejection of his own party’s calls for him to do so. As a congressman, he’d called on Bill Clinton to resign after the exposure of his affair. But there was a difference.