#Jerome Hiler

Text

The Brooklyn Rail front page features stills from the films of Jerome Hiler and Nathaniel Dorsky

Cover of the May 3rd, 2024 edition of The Brooklyn Rail. Stills from Jerome’s Words of Mercury and Nathaniel’s Triste

#thebrooklynrail#will epstein#illuminated hours#jerome hiler#interview#personal history#nathanieldorsky#nathaniel dorsky#art in conversation#words of mercury#triste#articles#film stills

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seen in 2024:

Cinema before 1300 (Jerome Hiler), 2023

#films#movies#stills#docs#documentary#art#Cinema before 1300#Jerome Hiler#Medieval#stained glass#Canterbury#2020s#seen in 2024

0 notes

Photo

Stan Brakhage, January 14, 1933 – March 9, 2003.

With Jerome Hiler, Nathaniel Dorsky, and Anne Waldman in 1998.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 Live & Onstage Programs Featuring Performances by Will Oldham and Terence Nance Added to San Francisco International Film Festival

2 Live & Onstage Programs Featuring Performances by Will Oldham and Terence Nance Added to San Francisco International Film Festival

A still from experimental filmmaker Jerome Hiler’s BAGATELLE II, who’s work will be played alongside Will Oldham, aka Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy’s original musical compositions during the Headlands and San Francisco Film Society special program PARALLEL SPACES: WILL OLDHAM AND JEROME HILER. “Parallel Spaces: Will Oldham and Jerome Hiler” and “18 Black Girls / Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Moments from Luminous Intimacy: The Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler.

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

Jerome Hiler in the San Francisco Chronicle's series "The City Exposed." Find his work, newly available in the Canyon catalog, here!

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

CTS #art musing | “Music Makes a City”

I was reading Artforum, and I came across an article entitled “Labor of Love”, which was about the work of Jerome Hiler’s. I wasn’t that familiar with the artist, but his work sounded interesting, so I googled him. I wanted to view the piece the article spoke about, and as usual, it was impossible to actually view the piece, Labor of Love, on-line (as it is with most video pieces). However, what I did find was a trailer to a feature-length documentary directed by Jerome Hiler called, Music Makes the City.

Quickly summarized, the filmis about a small, struggling, semi -professional orchestra in rural Kentucky, that was facing bankruptcy in 1948. So they came up with a novel idea; commissioning new work from composers from around the world. Of course, in 2012 this sounds completely un-novel, but there was one moment in the film when an older gentleman said:

“You have to understand nothing like this had ever happen before, and no one ever thought to do things this way. One conductor, one orchestra, not just learning but mastering the compositions of all these young unknown composers sometimes in the window of a few weeks… It was amazing, it was an extraordinary experience."

And, that was it; “It was an extraordinary experience”. That silly little line got me. The manner in which I got to it - how I discovered it in this cyclical way , made me realize that it is the search and pursuit of knowledge or inspiration, that is the epicenter of this magical place, which we (who is “we”? Artists?) all work from. That is temporal space where the best times are had. Those are the moments in which the best works are made. That is what fuels our purpose. It is in those moments, we find solutions that inspire the future.

It must be what Dan Graham meant when he said, “All artist are alike. They dream of doing something that’s more social, more collaborative, and more real than art”. It is as much about a sense of civic duty as it is about expression or creativity. Hiler echoes my belief that the documentary was meant as a challenge for all of us - a command, “To seize the moment of our time. To be inspired to pursue our loves”.

-Lynn del Sol

#Jerome Hiler#Music Makes the City#CTS musing#lynn del sol#art history#video#art#artist#CTSart#creative thriftshop#CTS artist#CTS event#press#CTS press

0 notes

Text

Max Goldberg on the slide lecture by Jerome Hiler for Film Comment Magazine

Heaven Can Wait was written in celebration of Jerome’s presentation of the slide lecture at MoMA to open the film series, The Illuminated Hours, a celebration of the films of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler at MoMA and the Anthology Film Archives.

This “live" presentation at MoMA is on the evening of Thursday, May 9th, 2024 at 7 in the evening.

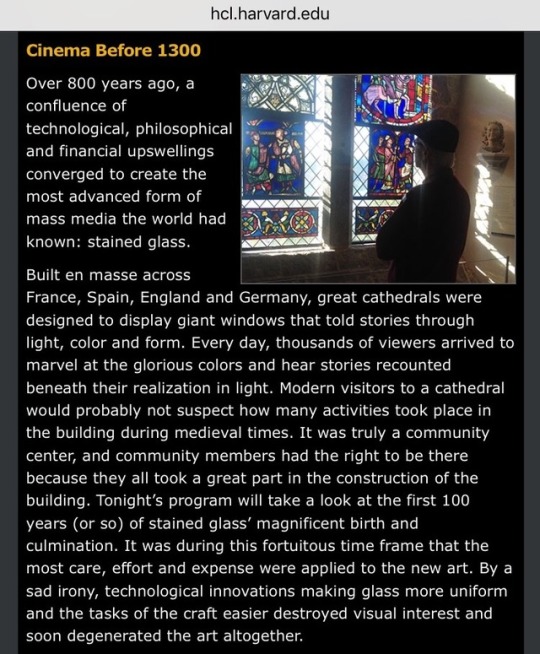

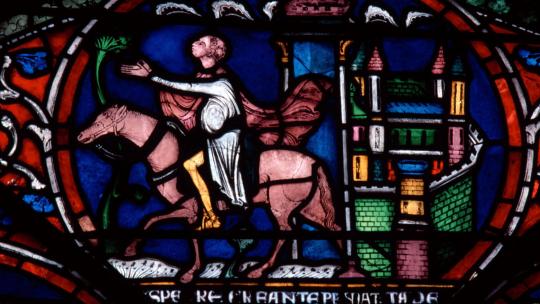

Cinema Before 1300

By Max Goldberg

Early in Cinema Before 1300, Jerome Hiler’s feature-length survey of medieval stained glass, the filmmaker explains that he first saw Chartres Cathedral in the pages of a book gifted to him in the mid-1960s by Charles Boultenhouse and Parker Tyler, elders of the era’s New York avant-garde. It took another 25 years or so for Hiler to travel to Europe to see the cathedral for himself. He brought a Nikon to photograph stained glass across France and England, sharing his 35mm slides with friends and, eventually, in a few public lectures. After one such presentation at the Harvard Film Archive in 2017, Hiler was persuaded by HFA Director Haden Guest to turn his slides into the discursive film that will show at the Museum of Modern Art next week, ahead of several programs of his and his partner Nathaniel Dorsky’s lush experimental films.

It feels odd to call Cinema Before 1300 an essay film, since the term has come to be associated with a riddling, theory-minded style. Hiler’s approach is closer to the classical ideal of the essay: lucid, companionable, amateur in the original sense (as in, “one who loves”). He is perfectly willing to concede the limits of his knowledge—“I don’t know what the significance of that is,” he says of the recurring figure of a king tugging at his collar like “an ancestor of Rodney Dangerfield”—but his exploration is nevertheless grounded in years of close looking and practical know-how. (In addition to making intensely lyrical films, Hiler has worked extensively, if privately, with glass.)

For those who might demur at the prospect of an old-school art-history lecture, it ought to be said that Hiler’s photographs are totally gorgeous. His framing shows the windows to great advantage, and the saturated color of his original 35mm slides is a perfect match for the brilliance of the stained glass. The narration approaches this visual index from a variety of angles: with a theological gloss on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’s idea of “light from divine darkness,” for instance, or a historical note on the cataclysmic fire that ripped through Chartres in 1194. Hiler muses on how the windows change with weather and time of day, making “many windows out of one”; offers a technical explanation of the perceptual effects of halation; argues for leaving the marks of age in any restoration; and marvels at all the pictorial detail that couldn’t have been seen by congregants—just as, we might note, the subtleties of his own richly detailed films invariably escape a first viewing.

It is rather amazing that a work so full of information should also feel so serene. Similar to the way in which large stained-glass windows are made from many smaller pieces of glass, Hiler divides Cinema Before 1300 into discrete sequences, each comprising a paragraph’s worth of narration and a few slides of the glories of Chartres, Saint-Denis, Canterbury, and other cathedrals. At the end of each stanza, Hiler finishes his talk and pauses for a few beats, allowing the glass to have the last word, and then repairs to darkness. He uses interleaving blackouts to the same rhythmic, almost respiratory effect in his lyrical films, but here the technique doubles back to the imagined space of the cathedral. “Darkness is the sacred setting that film and stained glass share,” Hiler reflects over an extended interval of black toward the beginning of the film. “Our overview begins in the early 12th century, a time when darkness was imbued with a powerful spiritual significance . . . It was not the darkness of negation; it was pregnant, life-giving, limitless, and timeless.”

The connection between the cathedral and the cinema goes well beyond the shared spiritual interplay of light and dark: there is also the sequential nature of early narrative art; the saints as movie stars, with “personalities . . . known, loved, and adopted by the populace”; the way the likeness of a window’s sponsor functioned like an executive-producer credit; and how certain tropes, like the devil perched on a person’s shoulder, have passed through time virtually unchanged. Leaving narrative aside, Hiler can’t resist mentioning how five densely patterned windows at York Minster resemble Stan Brakhage filmstrips, and we might just as easily see the mandala-minded Harry Smith in the alchemist’s rose at Notre-Dame or the 3D-obsessed Ken Jacobs in the frequently used blues and reds that produce a mesmerizing sense of “dimension without perspective.” Perhaps most salient is the medieval ideal of claritas, which, per Hiler, creates “an environment that [awakens] the mind through the senses”—very close indeed to the “devotional cinema” explored in Dorsky’s slim book of the same name.

In this telling, the first “death of cinema” can be dated back to 1241, when a Council of the Sorbonne ruling indirectly led to clear windows flooding cathedrals with daylight, banishing the necessary conditions for stained glass to work its magic. The fate of the cathedrals readily brings to mind the devolution of the great movie palaces, including, in just the past year, the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, Hiler and Dorsky’s longtime hometown. More particular to Hiler’s own craft, the historical subject also lends itself to thinking about what it means to stay true to an artistic lineage when the tide goes out. Hiler’s lament, late in Cinema Before 1300, that he watches his “world of culture and values disappear in daily installments” needs to be taken alongside the film’s testament to the remarkable persistence of material culture even through the most trying circumstances.

In a long interview included in the recent book Illuminated Hours: The Early Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, Hiler recalls that his very first shot with a movie camera was of a rose-colored piece of glass. A friend advised that instead of actually filming stained glass, Hiler should make his films themselves “be like stained glass.” Viewers can judge his success in the upcoming programs celebrating the book at MoMA and Anthology Film Archives, but Cinema Before 1300, like Hiler’s earlier documentary work, stands on its own two feet. A few weeks after watching the film at home, I went up to the Cloisters on a rainy day and found the stained-glass figures in the Early Gothic Room waiting for me, perfectly assured yet surprisingly familiar. Which is to say that Cinema Before 1300 leaves a long-lived afterimage—and its own measure of sanctuary.

Max Goldberg is an archivist and writer based in the Boston area.

#jerome hiler#nathaniel dorsky#max goldberg#film comment#film comment magazine#articles#illuminated hours

0 notes

Text

Will Epstein interviews Jerome Hiler and Nathaniel Dorsky for The Brooklyn Rail

Jerome Hiler along the Sacramento River

This interview is in reference to the semi-retrospective series of ten screenings at NY MoMA and the Anthology Film Archives scheduled for May, 2024

Brooklyn Rail Interview link Nathaniel Dorsky & Jerome Hiler with Will Epstein

#Will Epstein#interview#Jerome Hiler#Nathaniel Dorsky#illuminated hours#artinconversation#TheBrooklynRail

0 notes

Text

Jerome and Nathaniel will be celebrated at MoMA and Anthology Film Archives this month of May.

This ten program mini retrospective is to celebrate the publishing in English of a new book on the early years of their filmmaking titled Illuminated Hours, The Early Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler.

There will be seven hosted in person programs in New York at MoMA followed by three in person shows at Anthology Film Archives. This selection of films will open with Jerome Hiler’s slide lecture, Cinema Before 1300. The emphasis will both be on the early formative explorations and a selection of their later work from the last six years or so. Many new films will be screening in NY for the first time.

The series is online here; MoMA and Anthology Film Archives will be finalizing their screening schedules and updating their calendar pages.

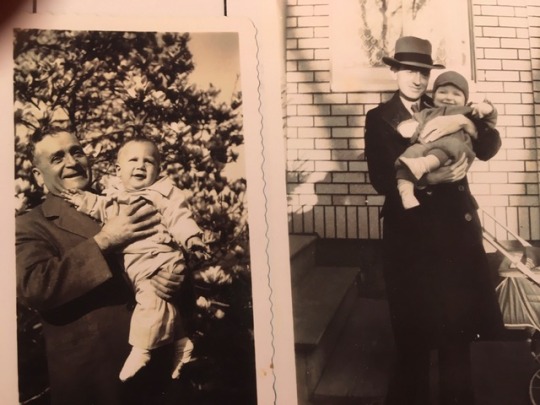

Nathaniel on the left, 1944, with his grandfather in the Bronx Botanical Gardens. Jerome on the right with his godfather, 1944, Jamaica, Queens

MoMA calendar link

Anthology Film Archives link

Illuminated Hours: The Early Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, by Francisco Algarín Navarro & Carlos Saldaña. English edition managed and edited by Nick Hoff. ISBN: 978-8-4940-9766-9

.

#nathanieldorsky#jerome hiler#MoMA#anthology film archives#illuminated hours#nathaniel dorsky#film screening#film shows#personal history and photos#in person

1 note

·

View note

Text

Film Comment Podcast interview of Nathaniel and Jerome discussing the New York years 1962 to 1964

Image from a film by David Brooks, Letter to D.H. in Paris

LINK: Audio podcast

Film Comment

Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler on NYC's Underground Cinema

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nathaniel Dorsky: Shimmering Golden Music

Extract from Notebook Interview

Article and interview with Nathaniel Dorsky by Maximilien Luc Proctor

A conversation with the American experimental filmmaker on the occasion of a Barcelona retrospective of his and Jerome Hiler’s films and a new book about them both.

Over the course of ten programs across five days in Barcelona this January, curators Francisco Algarín Navarro and Carlos Saldaña presented a career-spanning series devoted to American experimental filmmakers Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler. The series was curated to coincide with the release of a brand-new book, Illuminated Hours. Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, focused on the pair’s early years; meeting and struggling to understand the elusive medium of film. As is the case for all Lumière publications, it is a beautiful object, complete with full-color stills and archival documents. The bulk of the book consists of extensive interviews with Dorsky and Hiler conducted by Navarro and Saldaña, and features texts by curator Mark McElhatten among many others, and incorporates excerpts from prior interviews, including one I conducted with Hiler for Ultra Dogme last year. Illuminated Hours is currently only available in Spanish, with an English language version slated for later this year.

As Dorsky and Hiler exclusively screen their work directly from 16mm prints (rentable from Light Cone in Europe or Canyon Cinema in the U.S.), there were only two individual exceptions to this rule. Library (1970) was screened as a digital file, from a 2021 restoration by the Harvard Film Archive. A collaboration between the two filmmakers, Library is based on the old style “industrial”, highlighting the various community benefits of its namesake. Dorsky’s 17 Reasons Why (1985-87) was screened once from a print and was available to watch on a four-monitor (one for each of the 8mm frames shown simultaneously) constellation on a loop, from a 2020 digital scan done by MoMA. It is a delightfully playful whirlwind (I’m thinking here of a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it composition where Dorsky films his pants around his shoes while sitting on the toilet) which condenses the visual beauty from across his filmography into a metabolism more often associated with the work of someone like Joseph Bernard. Apart from his fascination with photographic beauty formed through dense reflections and thick, high contrast plays of striped shadows silhouetting over brightly sunlit people and objects, Dorsky often holds a shot until time allows itself to unfold so that a surprise may surface. They are simple surprises, but ones that often bring about great pleasure; take three women seen through a window, all wearing deep red clothing. When one changes position, she reveals a bottle of ketchup in their midst, perfectly suited for the occasion. When we are presented with a collection of minute glimmering lights, we wonder for a moment where they might originate, until Dorsky turns the aperture to reveal they are light reflected in the droplets on the hood of a car. In Love’s Refrain (2000-2001), a clear plastic to-go box is opened by the wind, leans backwards, and its own contents (a lonely plastic fork and styrofoam cup) slide into the center, forming a new arrangement for this found statue. It is an image in conversation with the plastic bag floating in the wind of Variations (1998). There are beautiful rippling lights seen in macro, manifested as out of focus orbs, ruptures of the universe, shimmering golden music.

Through Dorsky’s polyvalent montage he hopes that certain shots will be taken as reverberations of ones previously seen within a film—the edit is arranged intuitively yet strategically. The larger body of work supports and re-amplifies so many reverberations across the decades; Jerome Hiler appears numerous times throughout, as do endless bushes, shrubs, saplings and veteran trees. Text silhouetted and thrown onto unusual surfaces, human behavior when unaware (one presumes) they are being observed. Perhaps most fascinating are the infrequent yet recurring interludes of three to five shots of rapid movement through dense cross hatcheting created by shooting through an orange construction fence or by simply filming similarly shaped shadows intersecting with stairs—thrilling in their velocity within the context of such steady and measured work. Dorsky is interested in geometry and its permutations through movement, be they such rapid ‘stackings’ or the languid vibrations of nature reflected on the pulsating surface of a pond. So too do certain ideas reverberate across the pair’s collective body of work, though in less obvious ways. Where Hiler works with multiple exposures to overlap, echo, and strike lightning, Dorsky achieves his density of image in a single shot, with concrete, recognizable photography—we understand the literal images but not always the how or what of their surroundings. When we see a “pseudo-Hellenic bust” (to borrow from P. Adams Sitney’s apt description) lying on its side in Dorsky’s Threnody (2003-2004), it comes back to mind when we see the face of a similar figure in Hiler’s Words of Mercury (2010-2011), surrounded by a barren rural area in the background. In both cases the old world has fallen. Dorsky presents us with texts being written or copied down (by Hiler), but Hiler presents text itself (one screen-filling superimposition close-up of German text makes legible the name “Maria Rilke”). Hiler also creates text through the scratching of the film surface, such as in the notes he scrawls onto Marginalia. Immediately after stepping out of a Dorsky screening, some images remain in the mind’s eye with power, others vanish almost instantaneously—not for lack of visual virtuosity, but for their settling somewhere deeper in the mind than what is accessible on the surface. A few hours later certain images would return, but what truly astounded me was a shot which came to mind with complete clarity the following afternoon when I happened upon its analogous manifestation in the physical world: Dorsky’s camera careening into the flowers, leaning in closer to catch a pollinating bee, startlingly yellow in a sea of lavender, obstructing pedals pressed forward by the lens as it passed...

The entire Mubi Notebook article “Nathaniel Dorsky: Shimmering Golden Music” including the Maximilien Luc Proctor interview with Nathaniel Dorsky, is available online.

continue reading on Mubi homepage

Illuminated Hours. Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler Lumière

*

#Nathaniel Dorsky#Jerome Hiler#notebookmubi#maximilien luc proctor#barcelona#interview#library#francisco algarín#carlos saldaña#illuminated hours. nathaniel dorsky and jerome hiler#lumière#mark mcelhatten#ULTRA DOGMA#17 reasons why#love’s refrain#p. adams sitney#threnody#words of mercury#Marginalia#articles#Nathaniel speaking/audio/video

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illuminated Hours: The Devotional Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, ten screenings in Barcelona

Between January 13 and 17, 10 screenings dedicated to the film work of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler will take place in Barcelona. The film retrospective, "Illuminated Hours: The Devotional Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler", organized by Francisco Algarín Navarro and Carlos Saldaña, will be celebrated in three different venues: Xcèntric, the cinema of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, the Catalonian Cinematheque and ZumZeig Cinema. In addition to these screenings, between January 13 and 30, the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona will present the installation version of Nathaniel Dorsky's film 17 Reasons Why. The film cycle also includes a special screening on Sunday 15 in which the film Library will be shown, made in 1970 by Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler on the New Jersey public library network, along with the presentation of a new book, Illuminated Hours. Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, a publication edited by Francisco Algarín Navarro and Carlos Saldaña dedicated to more than forty years of shared life and filmmaking, and the reprint of the Spanish version of Devotional Cinema, both with the Spanish publishing house Lumière.

The program includes the following screenings:

Program 1

Xcèntric, the cinema of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Thursday, January 13, 7pm

Apricity, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2019, 16 mm, silent, 22’

Lamentations, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2020, 16 mm, silent, 14’

Ember Days, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2021, 16 mm, silent, 10’

Emanations, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2020, 16 mm, silent, 16’

Terce, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2021, 16 mm, silent, 16’

Program 2

Catalonian Cinematheque, Friday, January 14, 4:30pm

Ingreen Nathaniel Dorsky, 1964, 16mm, sound, 12’

A Fall Trip Home Nathaniel Dorsky, 1964, 16mm, sound, 11’

Summerwind Nathaniel Dorsky, 1965, 16mm, sound, 14’

Hours For Jerome Part 1 & 2 Nathaniel Dorsky, 1966-70/82, 16mm, silent, 45’

Program 3

Catalonian Cinematheque, Friday, January 14, 7:30pm

In the Stone House Jerome Hiler, 2012, 16mm, silent, 35’

New Shores Jerome Hiler, 1987, 16mm, silent, 35’

Bagatelle II Jerome Hiler, 2016, 16mm, silent, 20’

Program 4

Catalonian Cinematheque, Saturday, January 15, 4:30pm

Pneuma Nathaniel Dorsky, 1983, 16mm, silent, 28’

17 Reasons Why Nathaniel Dorsky, 1987, 16mm, silent, 20’

Alaya Nathaniel Dorsky, 1987, 16mm, silent, 28’

Program 5

Catalonian Cinematheque, Saturday, January 15, 7:30pm

Triste Nathaniel Dorsky, 1996, 16mm, silent, 18’

Variations Nathaniel Dorsky, 1998, 16mm, silent, 24’

Arbor Vitae Nathaniel Dorsky, 2000, 16mm, silent, 28’

Program 6

Xcèntric, the cinema of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Sunday, January 16, 12pm

Library, Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, 1970, 16 mm to digital, 17’

Presentation of the publication “Illuminated Hours. Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler” and the Spanish version of “Devotional Cinema”

Program 7

Xcèntric, the cinema of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Sunday, January 16, 6:30pm

Love’s Refrain, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2000-2001, 16 mm, silent, 22’

Threnody, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2003-2004, 16 mm, silent, 20’

The Visitation, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2002, 16 mm, silent, 18’

Program 8

Xcèntric, the cinema of the Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona, Sunday, January 16, 8pm

Words of Mercury, Jerome Hiler, 2010-2011, 16 mm, silent, 25’

Marginalia, Jerome Hiler, 2016, 16 mm, silent, 23’

Bagatelle I, Jerome Hiler, 2016-18, 16 mm, silent, 16’

Ruling Star, Jerome Hiler, 2019, 16 mm, silent, 22’

Program 9

ZumZeig Cinema, Monday, January 17, 7pm

Sarabande, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2008, 16mm, silent, 15’

Compline, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2009, 16mm, silent, 18’

Aubade, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2010, 16mm, silent, 11’

Winter, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2007, 16mm, silent, 18’

Program 10

ZumZeig Cinema, Monday, January 17, 9pm

The Return, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2011, 16mm, silent, 27’

August and After, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2012, 16mm, silent,18’

Intimations, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2015, 16mm, silent,18’

April, Nathaniel Dorsky, 2012, 16mm, silent, 26’

All films listed as silent will be shown at silent speed, 18 frames per second, except for 17 Reasons Why which ideally should be shown at 16 frames per second as it is in the digital installation.

.

#Nathaniel Dorsky#Jerome Hiler#Catalonian Cinematheque#zumzeig cinema#xcèntric#devotionalcinema#Nathaniel Dorsky Devotional Cinema#francisco algarín#carlos saldaña#Illuminated Hours. Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler#17 Reasons Why#library#Film Shows

2 notes

·

View notes