#Harsha Walia

Text

These kinds of liberal democratic institutions — like welfare, like health care, like child services and the immigration system — are literally institutions that are death machines and are intended to be that way.

But we don’t see it, because we don’t see or understand it in the same way as we might overt violence, but that’s what they were perfected to become.

Harsha Walia

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

"And the everyday unsanctioned movement of people—defying borders and risking death—is, in itself, worldmaking and homemaking. Without romanticizing or generalizing the politics of those on the move, we must recognize the sheer will and productive power they represent. In their determination for a different life, migrants and refugees subvert the multibillion-dollar global industry of barbed wire walls, drone surveillance, militarized checkpoints, and bureaucratic violence aimed at fatally deterring them. Revolutions bring no guarantees, but they do call on us to dream, listen, commune, act, struggle, dismantle, rematriate, create, to move and make anew." - Harsha Walia, There Is No 'Migrant Crisis,'" The Boston Review, November 16, 2022

#antifa#refugees welcome#antifascist#no one is illegal#antifascism#your borders kill#harsha walia#the boston review

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's really interesting and important to think about and talk about the solidarity between groups that experience different forms of oppression.

Neurodivergent people and physically disabled people can both experience ableism, but it can look different. People find out about some of my mental health diagnoses and decide they wouldn't trust me with children (regardless of how I actually act) or they wouldn't date me or hire me. But this can be different than some of the opression I face as a cane user, when people assume I am faking being disabled or that I only use a cane because I'm fat (the intersection of ableism and fatphobia). And yet they're still connected.

We also see this in racism -- there are specific and unique kinds of racism that different groups experience. For example, an Asian person in a non-Asian majority country being asked, "No, where are you really from?" is different than a Black person being followed around a store because they are Black, but these things are still connected.

We also see this in religion and spirituality -- for example, antisemitism is real and important to acknowledge, and so is islamophobia. For example, Jewish people being targeted with violence while trying to come together in houses of worship is different than people seeing a Sikh person and assuming they're Muslim and therefore a terrorist, but these things are still connected.

The discrimination and oppression I face as a bi person is different than the discrimination and oppression I face as a genderqueer person, and both of those are different than the discrimination and oppression I face as a demi aroace person, but they're also all still connected.

We see this with transphobia -- there are specific and unique kinds of transphobia that transfeminine people face and that transmasculine people face. We see this in the kinds of stereotypes we come across about each group, and the kinds of hate crimes that are committed, and the challenges each group faces when trying to date, have sex, get access to health care, or just go out to buy groceries. These things are different, but they're also still connected.

We see this with so many different things that I can't begin to cover here. And we see that many people are part of multiple communities affected by several of these forms of oppression at the same time.

Talking about this requires thoughtfulness, nuance, and balance. True solidarity requires us to be able to be aware of the different ways that we face oppression, to be cognizant and respectful of the differences, but to also resist the urge to position these differences in some sort of persistent hierarchy.

Harsha Walia says this more eloquently than I can:

"I think allies and accomplices have become identities in and of themselves, when in fact they are meant to be verbs—to signify ways of being and of doing, of relationship and relationality. It is impossible for any one person to be ‘an ally’ because we all carry multitudes of experiences and oppressions and privileges. Most people are simultaneously oppressed and simultaneously privileged, and even those are always specific and contextual.My paid work is in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the country. Unsurprisingly, this is a disproportionately racialized neighbourhood but there are many older cisgender white men. A straight white cisgender man who is homeless faces a harsher material reality than me on a daily basis—with minimal to no access to food, shelter, health care, or income. Reductively, one would say that I have class privilege in relationship to him. But it goes beyond that. Even taking into account that I might be able to count off more forms of oppression, the entirety of my material reality is more secure.For me that is where intersectionality falls short; it has become a static analysis and one of fixed categories that leads to oppressed/ally dichotomies. Anti-oppression analysis becomes rigid in its categorizations when the question becomes who is more oppressed, rather than engaging in a dialogue of how oppression, which is relational and contextual, is specifically manifesting. Oppression develops a strange quantifiable logic, a commodity that can be stocked up on. This isn’t to say I don’t believe in anti-oppression allyship, but rather that I question its reductionism in place of a fluid, contextual and relational practice."

Harsha Walia, “Dismantle & Transform: On Abolition, Decolonization, & Insurgent Politics”

#op#oppression#oppression olympics#ableism#racism#antisemitism#islamophobia#biphobia#exorsexism#discrimination#quote#Harsha Walia#allyship#intersectionality#am I the only one who remembers when people used to tag discrimination against mental health as saneism?#we have always been looking for ways to talk about the discrimination we face#we have always faced discrimination that manifests in different ways#we have always tried to find ways to honor our shared struggles but also articulate the ways our struggles can be different

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

View on Twitter

A proclamation like “Immigrants steal our jobs,” and its rejoinder, “Our economy needs immigrants” treats immigrants as commodities to be traded in capitalist markets and discarded if deemed defective.

—Harsha Walia

(Source)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Border & Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism by Harsha Walia

Conservatives and liberals alike conceive of US immigration policy as an issue of domestic reform to be managed by the state. Language such as "migrant crisis," and the often-corresponding "migrant invasion," is a pretext to shore up further border securitization and repressive practices of detention and deportation. Such representations depict migrants and refugees as the cause of an imagined crisis at the border, when, in fact, mass migration is the outcome of the actual crises of capitalism, conquest, and climate change. The border crisis, as I argue in the first part, is more accurately described as crises of displacement and immobility, preventing both the freedom to stay and the freedom to move. American liberals may demand an end to excessive violence against Latinx migrants and refugees, exemplified in their opposition to concentration camps or family separation, but they rarely locate immigration and border policies within broader systemic forces. A long arc of dirty colonial coups, capitalist trade agreements extracting land and labor, climate change, and enforced oppression is the primary driver of displacement from Mexico and Central America. Migration is a predictable consequence of these displacements, yet today the US is fortifying its border against the very people impacted by its own policies. Analyzing the border as part of historic and contemporary imperial relations, hence the term "border imperialism," forces a shift from notions of charity and humanitarianism to restitution, reparations, and responsibility. (p. 3)

***

“Detention of aliens seeking asylum was necessary to discourage people like the Haitians from setting sail in the first place.”

—Attorney General William French Smith (p. 48)

***

Detainees in Australian detention also routinely sew their lips shut. Self-mutilation, either as resistance to forced feeding during hunger strikes or as a desperate yet defiant form of protest, is commonplace in detention centers, including in Woomera and Baxter, and on Christmas Island, Manus Island, and Nauru. Children in detention suffer from intense trauma but also engage in their own forms of dissent. In 2014, a group of refugees on Nauru, including children, sewed their lips shut to reject a forcible transfer to Cambodia as part of a forty-five-million-dollar resettlement deal struck by Australia. The next year around Christmas, photographs of dozens of children incarcerated on Nauru were released, in which they held signs with the numbers of days of their incarceration, most marking over three years. During the global pandemic in 2020, detainees in detention centers across Australia held protests to demand their release. (p. 103)

***

The European Commission now requires most development, aid, and trade agreements with Middle Eastern and African countries to include readmission agreements, which obligate non-European countries to preemptively control migration and readmit all expelled deportees. (p. 109)

***

Most troubling about liberal welcome culture is the erasure of European complicity in creating displacement through colonial conquest, land theft, slavery, capitalist extraction, labor exploitation, and war profiteering. Refugees and migrants defying Fortress Europe do not require the variable empathy of Europeans; their movement is ultimately a form of decolonial reparations. Glossing over structural responsibility and restitution, the social grammar of benevolence maintains, as Ida Danewid argues, "A colonial and patronising fantasy of the white man's burden—based on the desire to protect and offer political resistance for endangered others—which ultimately does little to challenge established interpretations that see Europe as the bastion of democracy, liberty, and universal rights." Or as Ali, an Iranian refugee in Calais, crystallizes the liberal savior industrial complex: "Sundays in the Jungle: pity. Outside the Jungle: hatred." (pp. 122-23)

***

In analyzing labor migration programs worldwide, Daniel Costa and Philip Martin find notable similarities across jurisdictions. Low-wage migrant workers are tied to one employer by contracts and visas and cannot bring their children or other family members. They are subjected to dangerous working conditions, forced labor, long work hours without overtime pay, and wage theft. Most workers are indebted to recruiters. Workers face legal or de facto barriers to unionization, are denied access to labor protections and social services, and have no real path to permanent immigration status. Speaking out against abuse almost always results in retaliation, termination, deportation, and blacklisting. (p. 137)

***

Furthermore, racialized xenophobia blunts class consciousness and allows elites like Trump, who has full or partial ownership of five hundred companies, to effortlessly impose austerity measures and expand capital accumulation. In 1993 in Austria, brewing class antagonisms were shifted onto migrants by far-right forces who began calling for "Austria First," a referendum on immigration issues. More recently, a billboard campaign in Canada against "mass immigration" and in support of the far-right People's Party of Canada was paid for by an organization headed by a mining company CEO. The Brexit "Vote Leave" campaign, funded by five of the UK's richest businessmen, unveiled posters featuring refugees alongside the slogan "Breaking Point." Right-wing nationalism is a bourgeois nationalism, and in our struggles against capitalist austerity we must emphasize that our enemy arrives in a limousine and not on a boat. (pp. 202-03)

***

Today, growing demands by labor unions to keep jobs out of the hands of "foreign" workers as a purported defense against neoliberal globalization should concern us. The demand for increased enforcement against migrant workers reproduces the logic of scarcity upon which austerity depends, maintains the international division of labor upon which capitalism relies, and aligns with far-right racism. The perceived loss of national and economic sovereignty, as argued by both the far right and many labor organizations, is blamed on migrant workers, thus rendering their protection of the working class as racially and nationally inscribed. As Lauren Berlant notes, the "implicit whiteness and maleness of the original American citizen is thus itself protected by national identity." Instead, we should assert that migrant workers don't suppress wages; bosses and borders do. Labor movements must align with migrant worker organizations demanding an end to a system of indentureship that establishes highly racialized, gendered, and nationalist labor pools and regimes of citizenship. We need full immigration status and labor protections for all workers. This is similar to the call to decriminalize sex work and recognize it as work, instead of a punitive enforcement agenda that increases the manufactured vulnerability of sex workers. Ensuring labor protections and citizenship status is the most ethical and effective counter to the far right's anti-migrant racism. Otherwise, attacks on migrant workers—buttressed by ubiquitous anti-Indigenous, anti-Black, anti-Muslim, anti-Roma, and anti-Latinx racism—will continue to work as intended for capitalist interests: channeling irregular migration into precarious labor migration, lowering the wage floor for all workers, and expanding carceral governance. Justin Akers Chacón prophesizes that "at the center of the conflicts to come will be whether labor can internationalize its understanding of the class struggle, build unity between workers within and across borders, and not fall victim to the barrage of xenophobia, reactionary nationalism, and scapegoating. (p. 205)

0 notes

Text

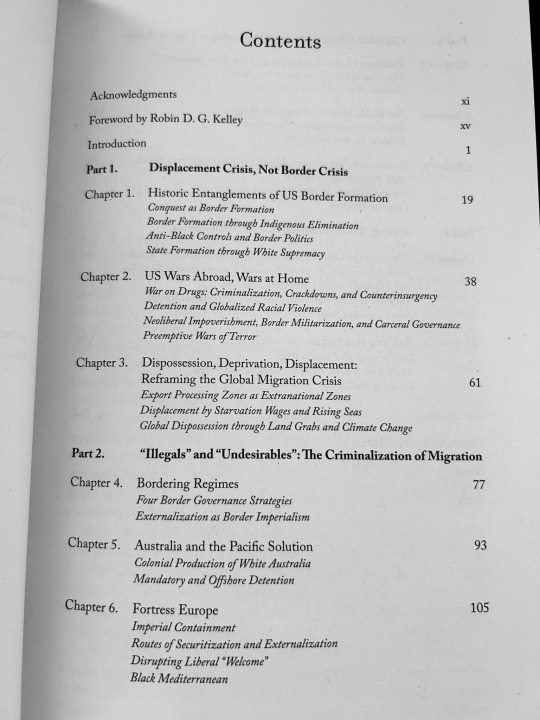

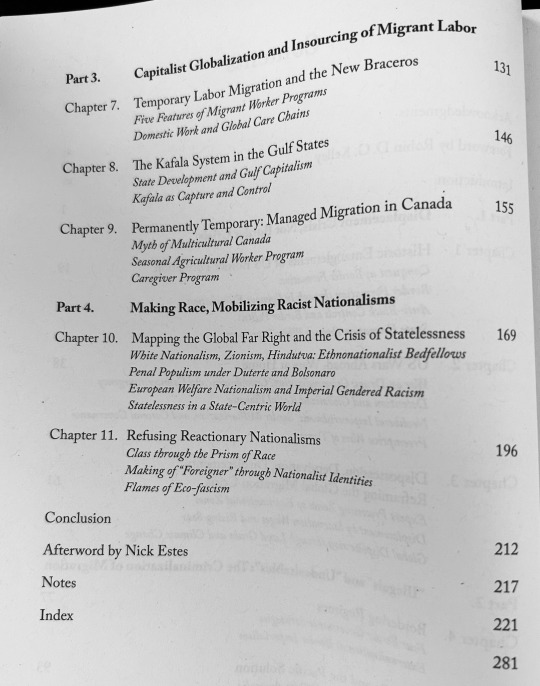

very exciting table of contents! That is a lot to cover in approx. 200 pages, I’m looking forward to reading this very much! from Border & Rule Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism by Harsha Walia

#teddy + my bookmark which is a prince of tennis 6 inch sticker of renji + Border & Rule by Harsha Walia#posting bc if u haven’t read this yet like me the table of contents has immediately drawn me in#I’m really into nonfiction this year which is exciting for me :]

0 notes

Quote

Empires crumble, capitalism is not inevitable, gender is not biology, whiteness is not immutable, prisons are not inescapable, and borders are not natural law.

Harsha Walia, Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

777 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Your posts are very enlightening and I'm inspired by how much you read. Might be a weird question and I'm sorry if it is but do you have any good book recommendations for a USAmerican trying to expand their worldview? I.e., histories of other countries/global regions, imperialism, etc.

i have some, but also recommend looking through @metamatar / @fatehbaz / @lafemmemacabre / @killy / @sawasawako / @handweavers (these are the mutuals that stand out to me but just the tip of the iceberg) &other blogs that have a more robust collection of resources –– i have learned a lot from them over the years!

that said, here are some books and authors whose oeuvres/at least multiple books i strongly recommend. different genres, and i'm not delineating between them as i am ideologically opposed to Doing That/creating epistemic hierarchies. obviously, that is particularly true given the nature of this ask. but it should be pretty clear what is considered a standard 'political/historical nonfiction' book and what...isn't!

authors:

Lisa Lowe

Jasbir Puar

Laila Lalami

Sara Ahmed

Trinh T. Minh-ha

Jamaica Kincaid

b. binaohan

Larissa Lai

Edwidge Danticat

Harsha Walia

Bhanu Kapil

books:

Atef Abu Saif, The Drone Eats With Me: A Gaza Diary

Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nervous Conditions

Pankaj Mishra, Bland Fanatics: Liberals, the West, and the Afterlives of Empire

Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live

Susan Williams, White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa

Minae Mizumura, The Fall of Language in the Age of English

Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism Without Borders

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Not a Nation of Immigrants

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother

Mimi Sheller, Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes

Marwa Helal, Ante Body

Aviva Chomsky, Central America's Forgotten History (NB: forgotten by usamericans, that is)

Raja Shehadeh, Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape

Moraga, Anzaldúa, and Bambara, eds., This Bridge Called My Back

Poupeh Missaghi, trans(re)lating house one

Marisol de la Cadena, Earth Beings

Kathryn Joyce, The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption

Bonaventure Soh Beje Ndikung, Pidginization as Curatorial Method: Messing with Languages and Praxes of Curating

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples

again, this appears as a long list, but is truly just a taste of what's out there. i hope it helps!

#ask#book rec#if u don't want to be tagged just msg me and ill untag you!#and also feel free to add on#anonymous

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

The links between empire, race making, and the border are perhaps best symbolized in the construction of the border wall itself: wire mesh recycled from a Japanese-American internment camp, repurposed Air Force landing strips and ground sensors from the Vietnam War, and Elbit Systems' "virtual wall" surveillance technology field-proven on Israel's apartheid wall.

– Harsha Walia, Border and Rule

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“You might be thinking that we seem to be talking about people smuggling rather than people trafficking, and that those two things are different. People smuggling is when someone pays a smuggler to get them over a border: in UK law, human trafficking is when someone is transported for the purposes of forced labour or exploitation using force, fraud, or coercion. It’s tempting to think of these as separate things, but there is no bright line between them: they are two iterations of the same system.

Let’s break it down. It is common for people to take on huge debts to smugglers to cross a border. So far, so good: clearly smuggling. But once the journey begins, the person seeking to migrate finds that the debt has grown, or that the work they are expected to undertake upon arrival in order to pay off the debt is different from what was agreed. Suddenly, the situation has spiralled out of control and they find themselves trying to work off the debt, with little hope of ever earning enough to leave. Smuggling becomes trafficking. The discourse of trafficking largely fails to help people in this situation, because it paints them as kidnapped and enchained rather than as trying to migrate. It therefore seeks to ‘rescue’ them by blocking irregular migration routes and sending undocumented people home— often the very last thing trafficked people want. Although they might hate their exploitative workplace, their ideal option would be to stay in their destination country in a different job or with better workplace conditions; an acceptable option would be to stay in the country under the current, shit working conditions, but the very worst option would be to be sent home with their debt still unpaid.

By viewing trafficking as conceptually akin to kidnap, anti-trafficking activists, NGOs, and governments can sidestep broader questions of safe migration. If the trafficked person is brought across borders unwillingly, there is no need to think about the people who will attempt this migration regardless of its illegality or conclude that the way to make people safer is to offer them legal migration routes. People smuggling tends to happen to less vulnerable migrants: those who have the cash to pay a smuggler upfront or have a family or community already settled in the destination country. People trafficking tends to happen to more vulnerable migrants: those who must take on a debt to the smuggler to travel and who have no community connections in their destination country. Both want to travel, however, and this is what anti-trafficking conversations largely obscure with their talk about kidnap and chains.

Our position is that no human being is ‘illegal’. People should have the right to travel and to cross borders, and to live and work where they wish. As we wrote in the introduction, border controls are a relatively new invention – they emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century as part of colonial logics of racial domination and exclusion. (ICE, the brutal American immigration enforcement police, was only created in its modern form in 2003; the previous iteration of it is as recent as the 1930s, an agency called Immigration and Naturalization Services.) The mass migrations of the twenty-first century are driven by human-made catastrophes – climate change, poverty, war – and reproduce the glaring inequalities from which they emerge. Countries in the global north bear hugely disproportionate responsibility for climate change, yet disproportionately close their doors to people fleeing the effects of climate choas, leaving desperate families to sleep under canvas amid snow at the edges of Fortress Europe. As migrant-rights organiser Harsha Walia writes, ‘While history is marked by the hybridity of human societies and the desire for movement, the reality of most of migration today reveals the unequal relations between rich and poor, between North and South, between whiteness and its others.’

A system where everybody could migrate, live, and work legally and in safety would not be a huge, radical departure; it would simply take seriously the reality that people are already migrating and working, and that as a society we should prioritise their safety and rights. Some journalists and policymakers argue that migration brings down wages. However, the current system, wherein undocumented people cannot assert their labour rights and as a result are hugely vulnerable to workplace exploitation, brings down wages by ensuring that there is a group of workers who bosses can underpay or otherwise exploit with impunity. Low wages and workplace exploitation are tackled through worker organising and labour law – not through attempting to limit migration, which produces undocumented workers who have no labour rights.

However, instead of starting from the premise of valuing human life, the countries of the global north enact harsh immigration laws that make it hard for people from global south countries to migrate. You don’t stop people wanting or needing to migrate by making it illegal for them to do so, you just make it more dangerous and difficult, and leave them more vulnerable to exploitation. Punitive laws may dissuade some from making the journey, but they guarantee that everyone who does travel is doing so in the worst possible conditions. Spending billions of dollars on policing borders actively makes this worse, without addressing the reasons people might want to migrate – notably, gross inequality between nations, which in large part is a legacy of colonial – and contemporary – plunder and imperialist violence.”]

molly smith, juno mac, from revolting prostitutes: the fight for sex workers’ rights, 2018

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I painstakingly drew this for hours last summer when churches were burning. I know and care for many IRS survivors. Some are really important people in my life. I saw the amount of grief rise up from inside them when news came from Kamloops. According to Wikipedia, there were at least 68 churches who were targeted with arson and vandalism. There are definitely more. This was an unprecedented wave of rage against the Church and its violence on Indigenous peoples.The TRC reported more than 6000 kids died in IRS schools. We will probably never know the real numbers. My dear friend who is a survivor of St-Marc-de-Figuery Residential School told me last summer that when the TRC audiences were about to close, people were basically just beginning to open up. What was recorded was just the surface of the abuse suffered there. Some things witnessed were too difficult to name. The TRC team asked the government to create a special task force on murdered children (in IRS) specifically, because there were too many hints to be just anecdotal, but their request was refused and we never got the state funded research.Schools are closed today and Indigenous families are left with sometimes insurmountable trauma that trickles down generations. But the church is still an active agent of colonization today. They sit on a power so immense we don’t even see its ramifications, especially as non-Indigenous ppl, sometimes completely outsiders to what happens in communities. The influence of the church is still active in protecting abusers, shaming people reclaiming traditional spirituality, colluding money, or refusing to share archives. In Quebec, the Oblats are denying information about their involvement in the disappearance of Innu, Atikamekw, Anishinabe children into the health system during the second half of the 20th century.Some have told me it’s not a settler’s place to speak in this matter. I want to say people’s faith is not my business, but fuck the church! Fuck the pope’s apology! I care for and support every anonymous arson attacker who wanted to avenge the victims of the Catholic Church since Jacques Cartier erected a giant cross in Gaspé in 1534thanks to Albrecht Dürer for the references, and yes I was totally making a nod at one of my fav pieces by @_mazatli_Alsoooo! Shout out to Harsha Walia for speaking out #burnitalldownyou can buy this print on zolamtl.storenvy.com

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone who is following for posting like revolutionary optimism and possible actions (canada) or other things you can do, i mostly post pretty pictures, little diary entries, and occasional anime meta. it's okay to unfollow, also mind your business abt my life..., and pls keep up with news sources such as al jazeera, the resistance news network (if you have unpacked war on terror racial anxieties about armed resistance), and journalists such as plestia, bisan, and motaz! you should be able to find their IGs and twitters relatively easy. also canadians, CPJME always has from home actions you can take, plus anti-imperial activists such as harsha walia or gada sasa. additionally, you may have ad-hoc groups or marching contingencies you can join for city-wide marches. if not, consider starting one with your friends! make a post about a lgbtq+ marching group to show up in solidarity and choose a meeting point for before and after the protest as a semi-safety plan! don't forget to mask at protests (prevent sickness and surveillance)

okay that's all from me, palestine will be free no matter what the western/zionist propaganda war is saying. we know this bcuz it's happened before. also i'm currently getting my covid and flu shots and you should too!!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mitt Romney Through a Counterinsurgency Lens

Last week I read a piece by Julia Conley in Common Dreams, Romney Admits Push to Ban TikTok Is Aimed at Censoring News Out of Gaza.

The article is about Mitt Romney and Antony Blinken in conversation as the keynote address at The Sedona Forum. The version of the article I first saw had the full address embedded. The page today has a 2-minute snippet posted by Arnaud Betrand at Twitter.com that really fits with the article. But I clicked to watch the full video and from the very start felt so much disdain for Mitt Romney, a gut-level disgust I hadn't felt about him before.

I know the feeling and also know that it often gets in my way about understanding. The solution isn't to ignore the feeling, which I probably can't do anyhow, but rather to take some time to attempt to better understand.

Later in the week I caught a live episode of Millennial's Are Killing Capitalism with Dylan Rodrigues at about the 50 minute mark. Rodrigues and MAKC host Jared Ware are discussan article by Rodrigues, How the Stop Asian Hate Movement Became Entwined with Zionism, Policing, and Counterinsurgency.

The lens which Rodrigues provided of counterinsurgency as a political logic was very useful to me for begining to unravel the sticky ball of disdain for Mitt Romney. I've paid too little attention to what. counterinsurgency is. here The conversation gave me plenty of pointers to learn more.

Dylan Rodrigues also peeled down another layer to the ways in which we can imagine the state. And he mentioned that he'd been studying the question with William Anderson and Dean Spade among others. I found a conversation with Harsha Walia, William Anderson, and Dean Spade at Barnard in 2022, No borders! No prisons! No cops! No war! No state?. The discussion opened up a view to imaging states and no-states.

A political logic which makes turning a blind eye towards genocide is appalling to me, but perhaps even mores shocking is the many ways I find myself entwined in that logic. Thinking about counter insurgency and the state more critically is necessary for imagining and doing something other which more consistent with what I value.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"At the global level, Western feminism has been complicit in racialized empire. Despite the fact that military occupations wreak havoc in the lives of women and children and the documentation of rape as a primary tool of war, many feminist organizations support imperialist interventions. From earlier “yellow peril” myths that warned of migrant Asian men ensnaring white women with opium to the more contemporary justifications of the occupation of Afghanistan as a mission to liberate Muslim women, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak portrays the cheerleading of civilizing crusades masked as feminist solidarity as “white men saving brown women from brown men.”

Liberal feminism is a handmaiden to cultural imperialism, essentializing communities of colour as innately barbaric. Women and queers are supposedly devoid of any agency — forced to veil, subjected to honour killings, coerced into arranged marriages. In the post-9/11 context, cultural imperialism is evident in debates about gender and Islam that force a singular feminism — secular, sexually expressive, and liberal autonomist — on women and queers of colour. Laws banning the niqab, for example, target Muslim women for public scrutiny, hate crimes, and state surveillance. Writing about the architecture of feminisms in the service of imperialism, Leila Ahmed charges, “Whether in the hands of patriarchal men or feminists, the ideas of western feminism essentially functioned to morally justify the attack on native societies and to support the notion of the comprehensive superiority of Europe.”

......

Rather than a feminism that strengthens racism, imperialism, and economic subjugation, feminism is most relevant in its subversion of the state, capital interests, gendered relations, and the policing of gender and sexual binaries. By challenging the ideologies of superiority and uniformity that underlie the dominant liberal framing of feminism, embracing a multitude of feminisms would diversify our understandings of how coercion and oppression is experienced, as well as resisted."

-

Reimagining feminism on International Women’s Day

by Harsha Walia March 4, 2015

How can we reimagine the dominant liberal framing of feminism? Embracing a multitude of feminisms can diversify our understandings of how oppression is experienced, as well as resisted.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A proclamation like “Immigrants steal our jobs,” and its rejoinder, “Our economy needs immigrants” treats immigrants as commodities to be traded in capitalist markets and discarded if deemed defective. Migrant justice must not endorse categories of desirable or undesirable, expectations of gratitude or assimilation, gestures of charitable humanitarianism, tropes of migrating to modernity, the commodification of labor to benefit capital accumulation, or state borders and other carceral regimes as legitimate institutions of governance.

Harsha Walia, Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

2K notes

·

View notes