#Harlem Hellfighters Band

Text

James Reese Europe: Pioneering Bandleader and Musical Trailblazer

Introduction:

James Reese Europe was a pivotal figure in the history of American music, a bandleader, composer, and arranger who helped shape the sound of the early 20th century. Born one hundred and forty-three years ago on February 22, 1881, in Mobile, Alabama, Europe rose to prominence during the ragtime era and became one of the most influential African American musicians of his time. His…

View On WordPress

#African American 369th Infantry Regiment#Benny Goodman#Clef Club#Clef Club Orchestra#George Gershwin#Harlem Hellfighters#Harlem Hellfighters Band#James Reese Europe#Jazz Composers#Jazz History#Paul Whiteman

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

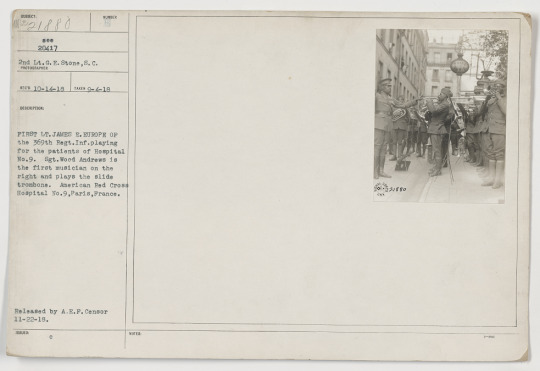

1st Lieutenant James Reese Europe and the 369th Infantry Regiment Band (the Harlem Hellfighters) play for patients in the American Red Cross Hospital No. 9, Paris, France, September 4, 1918.

Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer

Series: Photographs of American Military Activities

Image description: 1st Lieutenant Europe conducts a brass band who are standing in rows outside a building. All of the men are wearing WWI Army uniforms. A sign in the background reads HOTEL TUNIS. This regiment, the “Harlem Hellfighters,” was made up of all Black soldiers.

Transcription:

SUBJECT: 111SC 218880

NUMBER E

see 20417

2nd Lt. G. E. Stone, S.C.

PHOTOGRAPHER

REC'D 10-14-18

TAKEN 9-4-18

FIRST LT. JAMES E. EUROPE OF the 369th Regt. Inf. playing for the patients of Hospital No. 9. Sgt. Wood Andrews is the first musician on the right and plays the slide trombone. American Red Cross Hospital No. 9, Paris, France.

#archivesgov#September 4#1918#1910s#World War I#WWI#Black history#African American history#369th Infantry Regiment#Harlem Hellfighters#military#U.S. Army#band#music#trumpet#trombone#James Reese Europe

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Reese Europe & the Harlem Hellfighters

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

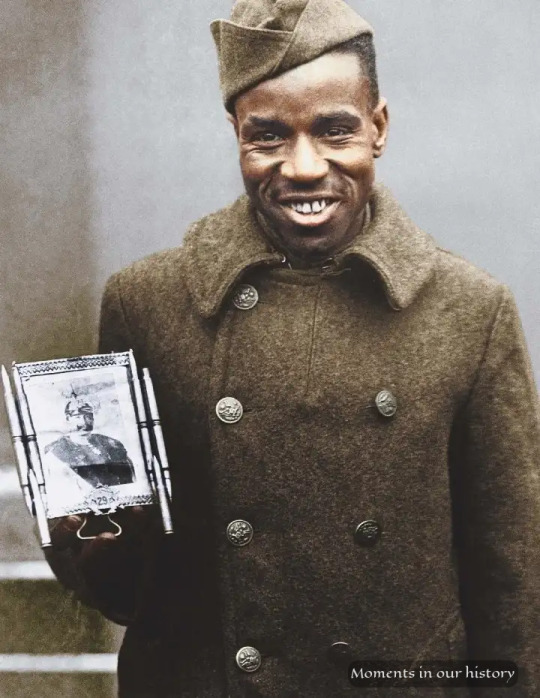

Fred McIntyre known as Devil's Man holds in his hands a portrait of the Kaiser framed with bullets that he took from a German Soldier

Colorized by Marina Amaral

Corporal Fred McIntyre served in World War I with the USA Army's 369th Infantry Regiment, a lavishly decorated regiment that was better known by its nickname: the Harlem Hellfighters. The Hellfighters, part of the New York National Guard, stood out for several reasons: uncommon courage, the exceptional ragtime-influenced brass band, and their Afroness. Only ten percent of the American soldiers were African.

In July 1918 they were fighting alongside the French along the Marne River. In fact, militarily they became French, as the 369th were integrated into the French Army. They wore hybrid uniforms (including the French Adrian helmet), carried Gallic rifles, and received French troop wine rations.

The Harlem Hellfighters accumulated more casualties on the Western Front than any other American regiment, but received numerous medals for their bravery. One member of the regiment, Henry Porter, nicknamed Black Death, was the first American to receive the prestigious Croix de Guerre, which was also awarded collectively to the entire 369th Regiment.

#african#fred mcintyre#devils man#devil's man#german soldier#kaiser#french#national guard#harlem#harlem hellfighters#black death#adrian#french army#kemetic dreams#african american

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOGAI BHM- Day 9!

happy BHM! today i’m going to be talking about the Tuskegee Airmen and Black people during world war 1 and 2!

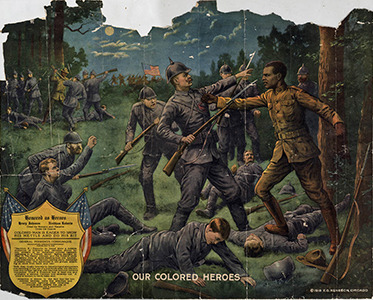

Black People During World War I-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of the Harlem Hellfighters, a group of Black men who served in World War 1. They are all wearing buttoned wool overcoats as part of their uniforms, and are all smiling and pumping their fists in the air in a cheerful, prideful way. End ID.]

Although they were treated inhumanely, many Black men were still eager to serve their country in the military- often because they hoped it would prove their humanity and their worth, as well as show others that they deserved equal rights. Sadly, this wasn’t always a reality.

When World War I was declared, around 20,000 Black men enlisted in military service. Later, that number dramatically increased to 700,000 Black men registered for military service- but the armed forces were segregated, and Black people weren’t allowed to serve in the Marines or the Navy. Additionally, the federal government provided no provisions for creating Black military units, training centers for Black soldiers, or protecting enlisted Black people.

Many Black people protested the injustices of the US Armed Forces, and though military training camps remained segregated, protesting led to the training and registration of 600 Black military officers at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. As suppressed as they were, Black fighters formed Black fighting units that provided vital support to troops on the ground in France.

One such unit was the 369th Regiment. A Black unit of soldiers, this unit was the longest-serving unit in a foreign army, and they never lost a single member- they were the first to arrive at key battles in France, provided integral support, and their success and tenacity earned them the title “Harlem Hellfighters”, as well as the “Black Rattlers”. The 369th Infantry Regiment operated a band that played music and performances for troops, which played a key role in inspiring those troops and greatly increased rapport with French troops. Another notable Black unit, the only to be commanded by Black officers, was the 370th Infantry Regiment, which also provided key battle support.

In France, the 200,000 Black troops deployed there were mainly relegated to labor units rather than fighting units- although they had signed up to fight, they instead were ordered to build railways, unload ships, and become mechanics and stevedores, rather than actually participate in combat.

Black fighters laid the foundations for success in World War I. When the war ended, many Black fighters returned home with a renewed sense of Black identity- and despite segregation, discrimination, and struggles within the Armed Forces, many Black men reported being treated better overseas than in the very country they were fighting for. This caused a huge wave of outcry for change, an outcry which helped usher in the Harlem Renaissance.

Black People During World War II-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of Black fighter pilots from World War II. The group is organized into two rows, the back one standing and the front one kneeling. They are all dressed in their fighters uniforms, dark jackets and pants, with a parachute strapped over their chest, and they’re in front of a plane labeled ‘TONDELAYO 75′. End ID.]

As war was mounting, the same obstacles that Black soldiers had faced in WWI were still happening in the Armed Forces. Black activists in charge of the March on Washington put pressure on FDR by threatening to protest and march if he didn’t do something about it, which resulted in his signing of Executive Order 8802, which forbade discrimination in the defense industry, a victory for Black activists although discrimination and segregation continued in the Armed Forces throughout the decade.

Mabel Staupers, a Black woman in charge of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, lobbied and advocated against racial discrimination and discriminatory policies in the Army Nurse Corps, which led to an amendment to the Nurses Training Bill barring racial bias- although in practice, the small cap number of Black nurses allowed in the Army Nurse Corps wasn’t lifted until 1944.

Throughout WWII, the Armed Forces were still segregated- and yet, despite that, over 1 million Black Americans served in WWII. Black soldiers served in such famous units as the 332nd Fighter Unit, which shot down more than 110 enemy planes over the course of nearly 200 missions, as well as the 761st Tank Battalion. The first Black soldier to win the Navy Cross was a man named Doris Miller, a steward who, despite not being trained to do so, manned machine guns during the Attack on Pearl Harbor and carried many people to safety. Another famous Black first of WWII was Major Charity Adams, who became the first Black woman to serve in the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

The most famous Black unit of fighters to come out of WWII is the Tuskegee Airmen. Up until WWII, Black people had been completely banned from the Air Force- they had never been allowed to be trained as fighter pilots or been allowed to join air units of the Armed Forces. That changed with the Tuskegee Airmen.

After Black activism pushed to start adding Black pilots to the Armed Forces, a plan was formed to start training a 99th Infantry of Black fighter pilots at Tuskegee Airfield, constructed for that very purpose in Alabama. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black aviators in any American unit and war, and within a few years, almost 1,000 Black pilots were trained at the Tuskegee Institute, with thousands more Black personnel working there. The Tuskegee Airmen left a profound legacy and impact on the Armed Forces.

Black soldiers were not the only Black people making massive impacts during WWII- the Black homefront was changing and contributing rapidly, through a campaign known as the ‘Double V Campaign’. Launched by a man named James G. Thompson with his letter titled “Should I Sacrifice to Life ‘Half-American’?” in a Pittsburgh newspaper, the Double V Campaign had two goals- gain victory on the warfront, and on the homefront.

The premise of the Double V Campaign was that Black Americans shouldn’t have to die at war for a country that didn’t see them as human or value that ultimate sacrifice. Black soldiers saw fighting as an opportunity to prove to the USA that they deserved to be seen as citizens, to be treated fairly, and that they were just as valuable to America as white people. Black civilians saw change on the warfront as inspiration to create change on the homefront.

Working with the federal government, a large amount of HBCUs began offering 50+ different classes on subjects relevant to homefront and warfront efforts during wartime, like mechanics, nutrition, photography, electronics, boat building, nursing, among others. These classes mobilized Black localities across the South to become active parts of homefront efforts- sustaining jobs of the soldiers who’d gone to war, producing machines to be sent overseas for soldiers, and more.

Black participation on the homefront during WWII was just as vital as Black participation in fighting, and was a large motivation behind the roots of the Civil Rights Movement. It was during WWII that Black communities started forming schools to teach about civil rights, nonviolent direct action, and literacy, and it was during WWII that student activist groups first started staging sit ins and other forms of protest, which became the heartbeat of the Civil Rights Movement in the following decades.

In 1948, Black activism and political pressure resulted in the signing of an order that completely desegregated the USA’s Armed Forces.

Summary-

During WWII, more than 100,000 Black soldiers served despite huge obstacles including segregation, and famous units like the Harlem Hellfighters emerged

During WWII, the Armed Forces were still segregated. Despite this, more than 1 million Black people served.

Black activism led to bans on racial bias in the defense industry and the Army Nurse Corps., and the Tuskegee Airmen emerged as the famous, first Black aviators ever

On the homefront, HBCUs and Black communities launched the Double V Campaign to gain victory in war and at home, and it included the work of HBCUs with the federal government to offer many courses adjacent to homefront and warfront responsibilities, training and mobilizing thousands of Black civilians on the homefront

The Armed Forces were officially desegregated in 1948

tagging @metalheadsforblacklivesmatter @neopronouns @epikulupu @justlgbtthings @transhaunting

Sources-

https://history.delaware.gov/world-war-i/african-americans-ww1/#:~:text=After%20the%20declaration%20of%20war,had%20registered%20for%20military%20service.

https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1429624/african-american-troops-fought-to-fight-in-world-war-i/

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/wwi/war

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/double-v-victory

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/african-americans-fought-freedom-home-and-abroad-during-world-war-ii#:~:text=More%20than%20one%20million%20African,and%20in%20the%20US%20military.

https://www.army.mil/article/233117/honoring_black_history_world_war_ii_service_to_the_nation

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/tuskegee-airmen-blackpast-org/#:~:text=The%20Tuskegee%20Airmen%20were%20the,their%20lives%20during%20that%20period.

https://www.tuskegeeairmen.org/

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1919 Group portrait of bandleader and soldier James Reese Europe and two of his musician-soldiers from the military band of 369th Infantry Regiment, commonly known as “The Harlem Hellfighters”. From The Maryland Center for History and Culture.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Memphis Blues

performed by Lt. James Reese Europe and the 369th "Harlem Hellfighters" Band, World War I

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lt. James Reese Europe and his regiment of African-American National Guardsmen, the 369th Infantry (the “Harlem Hellfighters”), returned in triumph from the Great War. They marched past cheering crowds all the way from the southern tip of Manhattan to Harlem, the city’s largest African-American neighborhood, which was at the time poised on the verge of the cultural flowering known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Lt.James Reese Europe leads the 369th Infantry band as it entertains wounded American soldiers at a Paris hospital, 1918. Courtesy Library of Congress

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lieutenant James Reese Europe (February 22, 1881 – May 9, 1919), known as Jim Europe, was an American ragtime and early jazz bandleader, arranger, and composer. He was the leading figure in the African American music scene of New York City. Eubie Blake called him the “Martin Luther King of music”.

He organized the Clef Club, a society for African Americans in the music industry. In 1912, the club made history when it played a concert at Carnegie Hall for the benefit of the Colored Music Settlement School. The Clef Club Orchestra, while not a jazz band, was the first band to play proto-jazz at Carnegie Hall. It is difficult to overstate the importance of that event in the history of jazz in the US. The Clef Club’s performances played music written solely by African American composers, including Harry T. Burleigh and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. His orchestra included Will Marion Cook, who had not been in Carnegie Hall since his performance as a solo violinist. Cook was the first African American composer to launch full musical productions, fully scored with a cast and story every bit as classical as any Victor Herbert operetta.

He was known for his outspoken personality and unwillingness to bend to musical conventions, particularly in his insistence on playing his style of music.

During WWI, he obtained a commission in the New York Army National Guard, where he fought as a lieutenant with the 369th Infantry Regiment (the “Harlem Hellfighters”) when it was assigned to the French Army. He went on to direct the regimental band to great acclaim. In February and March 1918, he and his military band traveled over 2,000 miles in France, performing for British, French, and American military audiences as well as French civilians. Europe’s “Hellfighters” made their first recordings in France for the Pathé brothers. The first concert included a French march, and the Stars and Stripes Forever as well as syncopated numbers such as “The Memphis Blues”, which, according to a description of the concert by band member Noble Sissle “... started ragtimitis in France”. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Music in the Post-War World

By Fernanda Matamoros

As we all know, World War I brought with it many consequences. Among them, focusing on the musical field, classical music was severely damaged due to the numerous composers and performers who died in battle or were severely marked by the things they had to live through. From this tragic event, musical pieces emerged that were either written especially for the cause or were born out of collective despair at such a tragedy.

After the end of the era of late Romanticism, Symbolism and Expressionism, European musical culture began to decline, and American popular music became increasingly important because of the war.

This event gave rise to a musical genre that was just beginning to take root in the United States, jazz. Thanks to the country's involvement in the battle, American soldiers were sent to the European continent, among them a black American regiment of musicians called the Harlem Hellfighters, who are credited with introducing jazz to France. During this period, patriotic songs became popular and helped to boost the morale of soldiers and civilians. Among the popular songs of the era was "Livery Stable Blues."

This musical genre not only quickly positioned itself as a favorite soundtrack of the war because of its upbeat and catchy characteristics, but also as an integrating cultural force. The jazz phenomenon continued even after World War II, being one of the most popular post-war genres alongside rock 'n' roll and country. After World War II, the musical themes and the music itself evolved, and singers such as Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra replaced the big bands of the past.

In the 50's, rock 'n' roll, with its innovative musical approach featuring electric guitars and drums, took off and was popularized by figures such as Elvis Presley and The Beatles. The 60's saw a new change in the music industry as they adapted to new technologies. Folk and rock music disappeared while jazz was reborn with exhibitors such as John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and blues and rhythm sounds emerged. In the following decades, various genres such as disco, hip hop and rap appeared. And undoubtedly, as the years go by, there will always be new musical styles that will leave their mark on musical history.

In conclusion, the World Wars not only marked humanity for life, but also completely changed the course of musical history and allowed the creation of unimaginable pieces that perhaps, in another historical context, would never have existed.

0 notes

Text

February 13, 1917 - Jazz Arrives in Europe

Pictured - James Reese Europe and the Harlem Hellfighters band.

The French had been living with war for years now, and the endless convoys of guns and soldiers no longer excited crowds as they once had. That was until the Americans began arriving in 1917. French crowds gawked at the endless ranks of young, tall soldiers from the New World, come to help out the Old. But it was their music, as much as their arms, that excited the French.

The U.S. Army’s 369th Infantry Regiment had arrived in Brest in December. There were many African Americans in the army, but the majority never left the harbor they had landed in in France. America’s Jim Crow politics meant a segregated army, and giving guns to black men was anathema to most white Americans. Most black men ended up in labor battalions, often without uniforms, but the 369th was luckier. Made up of black enlisted men with both black and white officers, the New Yorkers of the “Harlem Hellfighters” were destined for combat, and received training from experienced French troops that winter.

The Hellfighters would receive their share of attention in due time, but for now their band commanded the spotlight. The aptly named James Reese Europe had organized the regiment’s band out of some of the best jazz players in the country. Europe introduced America to the foxtrot in 1914. Now he introduced Europe to jazz.

The regimental band launched a series of concerts in Nantes in February 1918, and Europe would never sound the same again. The drums, saxophones, and horns were unlike anything the bewildered Nantais had ever seen. They loved every minute of it. “When the band had finished and the people were roaring with laughter, their faces wreathed in smiles, I was forced to say that this is just what France needed at this critical moment,“ wrote one of the band members, Noble Sissle, in his memoirs. The jazz age had begun.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Harlem Hell Fighters return to New York

Feb 12 1919 #OTD Harlem Hell Fighters (369th) who won the Croix De Guerre returning from #WW1. The 369th Infantry Regiment Harlem Hellfighters were in frontline trenches for 191 days, more than any other American unit. Racism in the American Army meant that the unit was transferred to serve under French command.

Front row, Left to Right:

Private Eagle Eye, Ed Williams

Lamp Light, Herbert Taylor

Private Leon Fraitor

Private Kid Hawk, Ralph Hawkins

Back row, Left to Right:

Sergeant H.D Prinas

Sergeant Dan Storm

Private Kid Woney, Joe Williams

Private Kid Buck Alfred Hanley

Corporal T.W. Taylor

Colourized by Jordan J. Lloyd

National Archives Identifier: 26431282

Local Identifier: 165-WW-127A-8

Feb 12 1919 Sgt Henry Johnson of the 369th Infantry Regiment, Harlem Hellfighters (Colourized by MadsMadsen.CH) arrives in New York harbor. From February 9-12 the Hellfighters arrived on troopships. On Wednesday #OTD February 12, 1919, men of the 369th Infantry Regiment disembarked the Swedish American liner Stockholm. Johnson was awarded the French Croix de Guerre for bravery during an outnumbered battle with German soldiers.

When they asked to march with the 42nd, nicknamed the Rainbow Division, he was denied his request and told "black is not a color of the rainbow." Yet on Feb 17 1919 they got their own parade with huge cheering crowds. While the Harlem Hellfighters marched down from 23rd Street and 5th Avenue to 145th Street and Lenox, Johnson had to ride in a car as he had a metal plate in his foot.

National Archives Identifier:533524

Image courtesy of the Tennessee State Library and Archives

Feb 12 1919 “The full caption for this item is as follows: [African American] Jazz Band and Leader Back with [African American] 15th New York. Lieutenant James Reese Europe who for four years [was] New York Society’s favorite orchestra (dance) leader formerly with Vernon Castle returned with his regiment the 369th Infantry.”

ARC Identifier: 533506

NAIL Control Number: NWDNS-165-WW-127(22)

210 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We Remember James Reese Europe and the Harlem Hellfighters

Even though this year's Memorial Day holiday has just passed us, we thank collector and researcher Steven Lasker for this story on James Reese Europe and the story of his Harlem Hellfighters. The Pathé and Victor records are prized collector's items today.

-Scott Wenzel

Read the article…

Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

「NICOLAS PICOU」

28 • PERFORMER • TAKEN BY TASHA

DIRECT FROM LE PETIT JOURNAL:

A charming smile, a silver microphone, and a voice like silk: it seems this was all it took for Nicolas Picou win the hearts of Paris. Mr. Picou has done us the kindness of returning, seven years after he served in the war with the Harlem Hellfighters, who brought his favoured form of jazz to France. If you have yet to hear him sing, you better hurry: tickets sell fast, and lineups go right out the door. Once you find your way in, you will surely be delighted by a mix of vibrant dance tunes, and sentimental melodies. When he is on stage, it is as if the audience knows exactly who he is – but in reality, there is little he has revealed about himself. Surely, someone so smooth must have secrets… and secrets are hard to keep in our city. Whether he brings you to your feet, or a tear to your eye, we are absolutely fascinated with this singer from the West.

ABOUT:

When Nicolas was a child, it was never called jazz. It was rag, and it was what he was raised on. With his parents both being musicians, and skilled ones at that, it was no wonder he showed musical talent. He started learning piano at a young age, and classical theory from his mother to go along with it. As his ambitions grew, his parents warned him as a child how difficult the life of a professional musician could be, and tried to steer him in other directions. Despite their efforts, it seemed he was in love.

The Picou family lived modestly. Despite being well-respected musicians of the community, they weren’t rolling in money. They could put food on the table, but they were grateful they only had one child to feed. Money was always a worry when Nicolas was growing up, so when he was a teenager, he proposed that he drop out of school to help. His parents were adamant that he would finish school as planned, but he found a way around that. He’d grown up in the clubs, watching the bands play, so he went to the owner and asked if he could help out somehow. Set up for the bands, clean up afterwards, and get something in return to bring home. He did this job for a while, before a band’s pianist was sick for the night, and he jumped in to help out. It became a common occurrence for him to play with bands when they needed an extra hand, and, when he was nineteen, he was invited to join one of the local groups for their tour.

It was during this tour that the United States made the decision to join the Great War. As soon as he was able to, Nicolas enlisted. However, instead of being sent back to Louisiana to join a regiment there, he and his band were sent to North Carolina with the New Yorkers. The training was hard work, harder labour than Nicolas ever had to do, but it was nothing compared to the war itself.

Nicolas’ unit was assigned to the French army in 1918, and his unit fought well. Men of Bronze, the French called them. The only reliefs he had were playing in the military band in the unit’s downtime, and writing letters home. After spending 191 days in the trenches, Nicolas was the only band member left of his New York tour.

It was bittersweet, returning home. The other soldiers in his unit were primarily from New York, they were already home; but he needed to return to New Orleans. Thankfully, his family was all safe, and Nicolas appeared to be relatively unharmed as well. However, he was haunted with everything he’d seen, sleep becoming hard to come by when he first arrived at home.

Sitting at a piano again took a long time, and even longer to get back on a stage. In the meantime, he worked as a labourer, or sometimes waited tables. Between being out of practice, and the guilt of leaving his fellow musicians behind in France, it took Nicolas nearly two years to perform again – but when he did, it was different. Instead of sticking to the piano, he began taking the microphone and singing as well, earning his share of head turns and nods of approval from the audience. His mother always told him he had a good voice, he took after her that way, you see, but it wasn’t until he started singing in the clubs that he realized it was more than a mother’s compliments.

People wanted distractions, that had always been Nicolas’ theory. It was certainly part of what kept him up there, flashing smiles at the audience and distracting even himself with what was now called jazz. In the years following, he became quite the name in New Orleans. One night after a show, a man flagged him down and told him he should go to Paris. It was a strange idea, one he was hesitant to consider – until it happened a second time, this time by a Frenchman who promised he could get Nicolas a few gigs in one of the Parisian jazz clubs.

Despite the war itself, Nicolas had fond memories of Paris. It was where he went after the battles ended, while they waiting to be sent home: it wasn’t so bad. Convinced it would be an adventure, Nicolas packed his bags. Almost exactly seven years since Armistice, Nicolas stepped back onto French soil.

CONNECTIONS:

The Sailor: You’ve played some rowdier places around Paris, and they seem to be a regular in such corners. You’re grateful for that, too - they’re clearly a fan, have a way of stopping trouble before it starts, and make for pretty swell company. They even helped you get a bit of work on the side, down on the quays, when you first arrived and times were tough. Maybe that makes you friends? Even if you’re not so sure about some of theirs...

The Sycophant: You’re a rising star, these days, and everyone wants to catch some of that shine. This new acquaintance has been hovering ever closer, lately; perhaps they and their whole society set can be a little much at times, but... hopefully their attention, and money, will help you hit ever bigger, brighter stages. This business, it’s all about who you know. There’s worse people to rub elbows with, you guess.

The Critic: They haven’t graced one of your performances with their presence - yet. Still, it’s easy to see why most of the artistic types in town are scared stiff of this one. Most. Not you. Not really. Okay, maybe a little, but they don’t need to know that. You’ve got what it takes, to make it here, to make it anywhere. Doesn’t matter what anyone says. Right?

Faceclaim & Pronouns: Lucien Laviscount, he/him

The Crooner is taken by Tasha, she/her.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Reese Europe

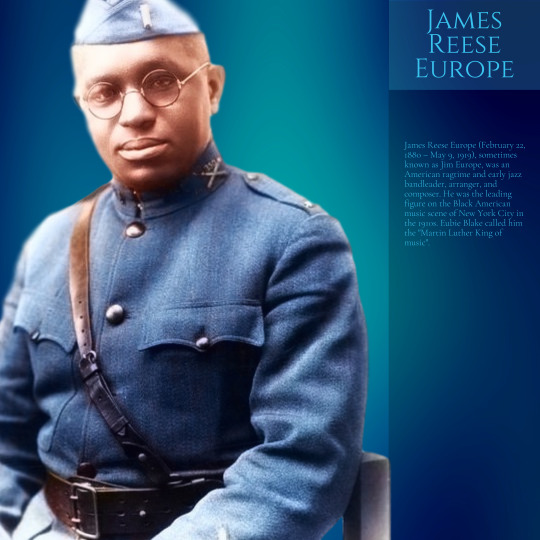

James Reese Europe (February 22, 1880 – May 9, 1919), sometimes known as Jim Europe, was an American ragtime and early jazz bandleader, arranger, and composer. He was the leading figure on the black American music scene of New York City in the 1910s. Eubie Blake called him the "Martin Luther King of music".

Early life

Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama, to Henry Jefferson Europe (1848–1899) and Loraine Saxon (maiden; 1849–1930). His family — which included four siblings, Minnie Europe (Mrs. George Mayfield; 1868–1931), Ida S. Europe (1870–1919), John Newton Europe (1875–1932), and Mary Loraine (1883–1947) — moved to Washington, D.C., when he was 10.

Europe moved to New York in 1904.

Band leader

In 1910, Europe organized the Clef Club, a society for Black Americans in the music industry. In 1912, the club made history when it played a concert at Carnegie Hall for the benefit of the Colored Music Settlement School. The Clef Club Orchestra, while not a jazz band, was the first band to play proto-jazz at Carnegie Hall. It is difficult to overstate the importance of that event in the history of jazz in the United States — it was 12 years before the Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin concert at Aeolian Hall, and 26 years before Benny Goodman's famed concert at Carnegie Hall. The Clef Club's performances played music written solely by Black composers, including Harry T. Burleigh and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Europe's orchestra also included Will Marion Cook, who had not been in Carnegie Hall since his own performance as solo violinist in 1896. Cook was the first black composer to launch full musical productions, fully scored with a cast and story every bit as classical as any Victor Herbert operetta. In the words of Gunther Schuller, Europe "... had stormed the bastion of the white establishment and made many members of New York's cultural elite aware of Negro music for the first time". The New York Times remarked, "These composers are beginning to form an art of their own"; yet by their third performance, a review in Musical America said Europe's Clef Club should "give its attention during the coming year to a movement or two of a Haydn Symphony".

Europe was known for his outspoken personality and unwillingness to bend to musical conventions, particularly in his insistence on playing his own style of music. He responded to criticism by saying, "We have developed a kind of symphony music that, no matter what else you think, is different and distinctive, and that lends itself to the playing of the peculiar compositions of our race ... My success had come ... from a realization of the advantages of sticking to the music of my own people." And later, "We colored people have our own music that is part of us. It's the product of our souls; it's been created by the sufferings and miseries of our race."

Some of Europe's best-known compositions include several that were co-composed with Ford Dabney (1893–1958) for the famed dancers Irene and Vernon Castle. The Castles regarded Europe's Society Orchestra among the best they had worked with and hired Europe late in 1913 as their preferred band leader with Dabney as their arranger.

Co-composed with Dabney for the Castles; Joseph W. Stern (1870–1934), publisherComposed soley by Europe for the Castles; G. Ricordi & Co., publisher

Co-composed with Dabney for Kern and Bolton's

Nobody Home

(1915)— Princess Theatre April 20, 2015, through June 1915; Maxine Elliott's Theatre June 7, 1915, through August 7, 1915

Co-composed with Dabney, lyrics by Gene Buck, for Ziegfeld's

Midnight Frolic,

sang by Nora Bayes; Francis, Day & Hunter Ltd., publisher

"Boy of Mine" (©1915)

In 1913 and 1914 he made a series of phonograph records for the Victor Talking Machine Company. These recordings are some of the best examples of the pre-jazz hot ragtime style of the U.S. Northeast of the 1910s. These are some of the most accepted quotes that are in place to protect the idea that the Original Dixieland Jass Band recorded the first jass (spelling later changed) pieces in 1917 for Victor. Unlike Europe's post-War recordings, the Victor recordings were not called nor marketed as "jazz" at the time, and were far from the first recordings of ragtime by Black American musicians.

Neither the Clef Club Orchestra nor the Society Orchestra were small "Dixieland" style bands. They were large symphonic bands to satisfy the tastes of a public that was used to performances by the likes of the John Philip Sousa band and similar organizations very popular at the time. The Clef Orchestra had 125 members and played on various occasions between 1912 and 1915 in Carnegie Hall. It is instructive to read a comment from a music review in the New York Times from March 12, 1914: "... the programme consisted largely of plantation melodies and spirituals [arranged such as to show that] these composers are beginning to develop an art of their own based on their folk material ..."

Military service

During World War I, Europe obtained a commission in the New York Army National Guard, where he fought as a lieutenant with the 369th Infantry Regiment (the "Harlem Hellfighters") when it was assigned to the French Army. He went on to direct the regimental band to great acclaim. In February and March 1918, James Reese Europe and his military band travelled over 2,000 miles in France, performing for British, French and American military audiences as well as French civilians. Europe's "Hellfighters" also made their first recordings in France for the Pathé brothers. The first concert included a French march, and the Stars and Stripes Forever as well as syncopated numbers such as "The Memphis Blues", which, according to a later description of the concert by band member Noble Sissle "... started ragtimitis in France".

Post-war career

After his return home in February 1919 he stated, "I have come from France more firmly convinced than ever that Negros should write Negro music. We have our own racial feeling and if we try to copy whites we will make bad copies ... We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others, and if we are to develop in America we must develop along our own lines." In 1919 Europe made more recordings for Pathé Records. These include both instrumentals and accompaniments with vocalist Noble Sissle who, with Eubie Blake, would later have great success with their 1921 production of Shuffle Along, which gives us the classic song "I'm Just Wild About Harry". Differing in style from Europe's recordings of a few years earlier, they incorporate blues, blue notes, and early jazz influences (including a rather stiff cover record of the Original Dixieland Jass Band's "Clarinet Marmalade").

Death

On the night of May 9, 1919, Europe performed for the last time. He had been feeling ill all day, but wanted to go on with the concert (which was to be the first of three in Boston's Mechanics Hall). During the intermission Europe went to have a talk with two of his drummers, Steve and Herbert Wright. After Europe criticized some of their behavior (walking off stage during others' performances), Herbert Wright became very agitated and threw his drumsticks down in a seemingly unwarranted outburst of anger. He claimed Europe did not treat him well and that he was tired of getting blamed for others' mistakes. He lunged for Europe with a penknife and was able to stab him in the neck. Europe told his band to finish the set and he would see them the next morning. To Europe and his band the wound seemed superficial. As he was carried away, he told them "I'll get along alright." At the hospital, they could not stop the bleeding and he died hours later.

News of Europe's death spread fast. Composer and band leader W. C. Handy wrote: "The man who had just come through the baptism of war's fire and steel without a mark had been stabbed by one of his own musicians ... The sun was in the sky. The new day promised peace. But all the suns had gone down for Jim Europe, and Harlem didn't seem the same." Europe was granted the first ever public funeral for a black American in the city of New York. Tanney Johnson said of his death: "Before Jim Europe came to New York, the colored man knew nothing but Negro dances and porter's work. All that has been changed. Jim Europe was the living open sesame to the colored porters of this city. He took them from their porters' places and raised them to positions of importance as real musicians. I think the suffering public ought to know that in Jim Europe, the race has lost a leader, a benefactor, and a true friend."

At the time of his death, he was the best-known black-American bandleader in the United States. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1918 James Reese Europe leads his Harlem Hellfighters band in a concert for fellow soldiers at the American Red Cross Hospital number five in Paris. From The Daily Mail.

13 notes

·

View notes