#Hadrian's Wall

Text

Sycamore Gap, Hadrian's Wall, Northumberland

So sad to learn that our beautiful tree has been vandalised overnight.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Relief Showing Mithras Being Born From The Cosmic Egg, Housesteads Mithraeum, Hadrian's Wall, Great North Museum, Hancock, Newcastle upon Tyne

#Mithras#Mithraeum#Temple of Mithras#roman#romans#roman living#roman empire#roman army#Hadrian's Wall#Newcastle#archaeology#stonework#relic#artefact#ancient craft#ancient living#ancient cultures#deity#cult

477 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some absolute cunt has cut down the most iconic tree in my region, probably in England

The sycamore has stood at what's known as Sycmore Gap, the spot where Hadrian's Wall dips from one hill to the next, for around 300 years. It was made famous after featuring in the Kevin Costner Robin Hood movie in 1991 and gets hundreds of visitors a day, even in the middle of winter

Countless people have got engaged there and had their ashes spread at the beloved spot

What was surely the most photographed individual tree in Britain is now gone

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hadrian’s Wall, UK (by Tobias Krams)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bless the young man who hiked 3 hours to plant a new sycamore tree

#Hadrian's Wall#Northumberland#sycamore gap#twitter post#English countryside#Roman Britain#vandalism#British history#empathy#justice#sapling#rural landscape#felled tree#UK

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aurora Borealis over Sycamore Gap, Hadrian's Wall

Photo by Guy Edwardes

#aurora#aurora borealis#pink#pink sky#green#green sky#colorful sky#sky photography#hadrian's wall#nature

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

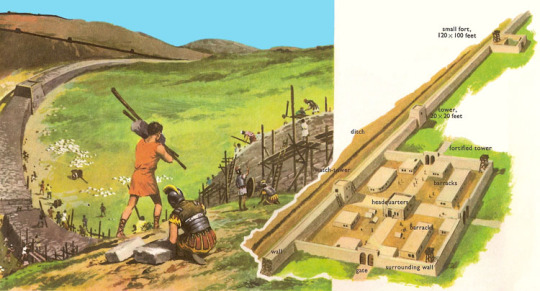

The Romans Cause a Wall to Be Built for the Protection of the South, William Bell Scott, 1857

#art#art history#William Bell Scott#historical painting#ancient history#Ancient Rome#Roman Empire#Roman history#Roman Britain#Hadrian's Wall#Pre-Raphaelite#Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood#pre-raphaelisme#British art#Scottish art#19th century art#Victorian period#Victorian art#oil on canvas#National Trust

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sycamore Gap, Hadrian's Wall, Northumberland

(C) do not use, edit, reupload.

#you may recognise it from a certain kevin costner film#sycamore gap#hadrian's wall#english countryside#non monster post#ghosti's photography#i found some old photos so i figured i'd share them here for funsies

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver Medusa Medal Found at Vindolanda

The snake-covered head of Medusa was found on a silver military decoration at a Roman auxiliary fort in England.

A nearly 1,800-year-old silver military medal featuring the snake-covered head of Medusa has been unearthed in what was once the northern edge of the Roman Empire.

Excavators discovered the winged gorgon on June 6 at the English archaeological site of Vindolanda, a Roman auxiliary fort that was built in the late first century, a few decades before Hadrian's Wall was constructed in A.D. 122 to defend the empire against the Picts and the Scots.

The "special find" is a "silver phalera (military decoration) depicting the head of Medusa," according to a Facebook post from The Vindolanda Trust, the organization leading the excavations. "The phalera was uncovered from a barrack floor, dating to the Hadrianic period of occupation."

Medusa — who is known for having snakes for hair and the ability to turn people into stone with a mere glance — is mentioned in multiple Greek myths. In the most famous story, the Greek hero Perseus beheads Medusa as she sleeps, pulling off the feat by using Athena's polished shield to indirectly look at the mortal gorgon so that he wouldn't be petrified, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Roman culture drew on Greek myths, including Medusa's story. During the Roman age, Medusa was seen as apotropaic, meaning her likeness was thought to repel evil, John Pollini, a professor of art history who specializes in Greek and Roman art and archaeology at the University of Southern California, told Live Science. Pollini was not involved in the find at Vindolanda.

"From Greek times on, this is a potent apotropaic to ward off bad things, to keep bad things from happening to you," Pollini said. Medusa's serpent-surrounded head is also seen on Roman-era tombs, mosaics in posh villas and battle armor. For instance, in the famous first-century mosaic of Alexander the Great from Pompeii, Alexander is depicted with the face of Medusa on his breastplate, Pollini noted.

Medusa is also featured on other Roman-era phalerae, but the details vary. For instance, the Vindolanda Medusa has wings on her head. "Sometimes you see her with wings, sometimes without," Pollini said. "It probably indicates she has the ability to fly, sort of like [the Roman god] Mercury has little wings on his helmet."

Because phalerae were awarded for "valor in battle," military men would attach them to straps and wear them during local parades, Pollini said, noting that the discovery of the Vindolanda phalera is rare.

"There aren't very many of them, obviously, because they were a precious metal," he said. "Eventually, most of them were probably melted down."

Many phalerae are found in burials, but the Vindolanda one appears to be lost. "This isn't something you would toss away," Pollini said.

The silver artifact is now undergoing conservation at the Vindolanda lab. It will form part of the 2024 exhibition of finds from the site.

By Laura Geggel.

#Silver Medusa Medal Found at Vindolanda#Hadrian's Wall#silver#silver medal#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art#roman legion

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am absolutely devastated that some fucking gutless vandal has felled the Sycamore Gap. This centuries old tree stood in a dip in Hadrian's Wall and has become one of the most famous and photographed trees in England, in part because of its use in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves - and now it's gone. It's a fucking tragedy, too, that it was cut down on the very same day that the UK State of Nature report revealed that wildlife of all kinds in the UK is in severe decline.

Here's the Milky Way seen from Sycamore Gap, Hadrian's Wall, in 2022. Photographer: Daniel Monk

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last Wednesday night, Britain was robbed of one of its best-loved trees. Mike Pratt, the CEO of Northumberland Wildlife Trust, describes the venerable, now-recumbent sycamore at Sycamore Gap on Hadrian’s Wall as a “totem tree; a touch point in the landscape”.

But the tree, standing alone in a national park, also reminded some of how nature-depleted England is. As environmentalist Ben Goldsmith said at the time: “That someone would have destroyed this iconic tree is beyond comprehension; but what’s even more shocking is that this was pretty much the only tree in that entire landscape. Our national parks can and should be so much better.”

According to Northumberland Wildlife Trust’s latest estimates, just 7% of Northumberland meets the criteria needed for the UK government to fulfil its commitment to protect and prioritise 30% of the landscape for nature by 2030 – which is a little higher than the 5% average across England as a whole.

While Goldsmith overstates the case somewhat, low tree cover does partly explain why Northumberland is sometimes called the “land of far horizons”. The most remote and least populated of England’s national parks, its rolling hills are swathed by expansive areas of open moor, peatland, as well as large forestry plantations.

In common with most other national parks in Britain, much of this land is grazed by sheep and cattle. As Pratt explains, over decades and centuries, agriculture has gradually become more intensive, with the result that areas of the national park are now almost devoid of trees and “feel a little bit industrial in parts”, he says. This is not the fault of individual farmers, Pratt argues. “It’s just that no one’s ever made any big decisions about what it should look like, probably since Roman times.”

Now, the felling of the tree at Sycamore Gap has given local communities and land managers a reason to reflect on, and make some serious choices about, how this landscape should look and function in the years to come.

A vision of renewal

From Pratt’s perspective, the corridor of land that roughly follows Hadrian’s Wall, from England’s east coast to west, is “possibly the biggest opportunity for a wilder landscape in England”.

On Wednesday, Northumberland national park authority announced its plans for how one part of that corridor would be renewed, with a new project signalling “a transformative shift towards a nature-first approach to land management”.

The project has been two years in the planning, but unveiling it this week, in the immediate aftermath of loss of the region’s most famous tree, felt like a fitting riposte to that crime. Tony Gates, chief executive of the National Park Authority, explained in a press release that his team decided it was imperative to seize the moment. “We are living through a nature crisis, a climate crisis and a wellbeing crisis,” he writes. “We must use this strength of feeling to drive change, for nature recovery and for our health and wellbeing.”

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The best preserved 'Lorica Segmentata', Roman Plate Armour in the world to date, Corbridge Roman Site Museum, Hadrian's Wall, Northumberland

#roman#roman armour#roman soldiers#roman army#roman style#roman living#hadrian's wall#romans#roman empire#roman military#roman fort#roman town#roman design#archaeology#ancient living#ancient culture#relic#artefact#roman metalwork

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is pretty damn horrible.

You might recognise this iconic tree from Robin Hood Prince of Thieves - the bit where they pretend Hadrian's Wall is somewhere near Dover.

It's also genuinely beloved and was voted tree of the year 2016.

If you ever wanted to visit this bit of the wall and look at this tree, you can't now. Ever. It's gone. For everyone.

People on Mastodon are saying it's probably been done to get back at the National Trust because they own that part of Hadrian's Wall and are not well liked in the area, but I can't imagine any reason for doing this that makes it less monstrous.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 24th, 76AD, is the probable date of birth of Publius Aelius Hadrianus, who built Hadrian’s Wall.

Right let’s start with the myth, a lot of people believe it marks the border between Scotland and England, and never has. In fact, the wall predates both kingdoms, while substantial sections of modern-day Northumberland and Cumbria – both of which are located south of the border – are bisected by it.

This post is a lot longer than I would normally do, Hadrian himself ruled for over 30 years , and the Roman Empire were in Britain for over 350 years. I've taken this post from the Smithsonian web site as I'm tied up trying to do other things this morning

Stretching 80 miles from the Irish Sea in the west to the North Sea in the east, Hadrian’s Wall in northern England is one of the United Kingdom’s most famous structures. But the fortification was designed to protect the Roman province of Britannia from a threat few people remember today—the Picts, Britannia’s “barbarian” neighbours from Caledonia, now known as Scotland.

By the end of the first century, the Romans had successfully brought most of modern England into the imperial fold. The Empire still faced challenges in the north, though, and one provincial governor, Agricola, had already made some military headway in that area. According to his son-in-law and primary chronicler, Tacitus, the highlight of his northern campaign was a victory in 83 or 84 A.D. at the Battle of Mons Graupius, which probably took place in southern Scotland. Agricola established several northern forts, where he posted garrisons to secure the lands he’d conquered. But this attempt to subdue the northerners eventually failed, and Emperor Domitian recalled him a few years later.

It wasn’t until the 120s that northern England got another taste of Rome’s iron-fisted rule. Emperor Hadrian “devoted his attention to maintaining peace throughout the world,” according to the Life of Hadrian in the Historia Augusta. Hadrian reformed his armies and earned their respect by living like an ordinary soldier and walking 20 miles a day in full military kit. Backed by the military he had reformed, he quelled armed resistance from rebellious tribes all over Europe.

But though Hadrian had the love of his own troops, he had political enemies—and was afraid of being assassinated in Rome. Driven from home by his fear, he visited nearly every province in his empire in person. The hands-on emperor settled disputes, spread Roman goodwill, and put a face to the imperial name. His destinations included northern Britain, where he decided to build a wall and a permanent militarized zone between “enemy” and Roman territory.

Primary sources on Hadrian’s Wall are widespread. They include everything from preserved letters to Roman historians to inscriptions on the wall itself. Historians have also used archaeological evidence like discarded pots and clothing to date the construction of different portions of the wall and reconstruct what daily life must have been like. But the documents that survive focus more on the Romans than the foes the wall was designed to conquer.

Before this period, the Romans had already fought enemies in northern England and southern Scotland for several decades, Rob Collins, author of Hadrian's Wall and the End of Empire, says via email. One problem? They didn’t have enough men to maintain permanent control over the area. Hadrian’s Wall served as a line of defense, helping a small number of Roman soldiers shore up their forces against foes with much larger numbers.

Hadrian viewed the inhabitants of southern Scotland—the “Picti,” or Picts—as a menace. Meaning “the painted ones” in Latin, the moniker referred to the group’s culturally significant body tattoos. The Romans used the name to refer collectively to a confederation of diverse tribes, says Hudson.

To Hadrian and his men, the Picts were legitimate threats. They frequently raided Roman territories, engaging in what Collins calls “guerilla warfare” that included stealing cattle and capturing slaves. Starting in the fourth century, constant raids began to take their toll on one of Rome’s westernmost provinces.

Hadrian’s Wall wasn’t just built to keep the Picts out. It likely served another important function—generating revenue for the empire. Historians think it established a customs barrier where Romans could tax anyone who entered. Similar barriers were discovered at other Roman frontier walls, like that at Porolissum in Dacia.

The wall may also have helped control the flow of people between north and south, making it easier for a few Romans to fight off a lot of Picts. “A handful of men could hold off a much larger force by using Hadrian’s Wall as a shield,” Benjamin Hudson, a professor of history at Pennsylvania State University and author of The Picts, says via email. “Delaying an attack for even a day or two would enable other troops to come to that area.” Because the Wall had limited checkpoints and gates, Collins notes, it would be difficult for mounted raiders to get too close. And because would-be invaders couldn’t take their horses over the Wall with them, a successful getaway would be that much harder.

The Romans had already controlled the area around their new wall for a generation, so its construction didn’t precipitate much cultural change. However, they would have had to confiscate massive tracts of land.

Most building materials, like stone and turf, were probably obtained locally. Special materials, like lead, were likely privately purchased, but paid for by the provincial governor. And no one had to worry about hiring extra men—either they would be Roman soldiers, who received regular wages, or conscripted, unpaid local men.

“Building the Wall would not have been ‘cheap,’ but the Romans probably did it as inexpensively as could be expected,” says Hudson. “Most of the funds would have come from tax revenues in Britain, although the indirect costs (such as the salaries for the garrisons) would have been part of operating expenses,” he adds.

There is no archaeological or written record of any local resistance to the wall’s construction. Since written Roman records focus on large-scale conflicts, rather than localized kerfuffles, they may have overlooked local hostility toward the wall. “Over the decades and centuries, hostility may still have been present, but it was probably not quite as local to the Wall itself,” says Collins. And future generations couldn’t even remember a time before its existence.

But for centuries, the Picts continued to raid. Shortly after the wall was built, they successfully raided the area around it, and as the rebellion wore on, Hadrian’s successors headed west to fight. In the 180s, the Picts even overtook the wall briefly. Throughout the centuries, Britain and other provinces rebelled against the Romans several times and occasionally seceded, the troops choosing different emperors before being brought back under the imperial thumb again.

Locals gained materially, thanks to military intervention and increased trade, but native Britons would have lost land and men. But it’s hard to tell just how hard they were hit by these skirmishes due to scattered, untranslatable Pict records.

The Picts persisted. In the late third century, they invaded Roman lands beyond York, but Emperor Constantine Chlorus eventually quelled the rebellion. In 367-8, the Scotti—the Picts’ Irish allies—formed an alliance with the Picts, the Saxons, the Franks, and the Attacotti. In “The Barbarian Conspiracy,” they pillaged Roman outposts and murdered two high-ranking Roman military officials. Tensions continued to simmer and occasionally erupt over the next several decades.

Only in the fifth century did Roman influence in Britain gradually dwindle. Rome’s already tenuous control on northern England slipped due to turmoil within the politically fragmented empire and threats from other foes like the Visigoths and Vandals. Between 409 and 411 A.D., Britain officially left the empire.

The Romans may be long gone, but Hadrian’s Wall remains. Like modern walls, its most important effect might not have been tangible. As Costica Bradatan wrote in a 2011 New York Times op-ed about the proposed border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, walls “are built not for security, but for a sense of security.”

Hadrian’s Wall was ostensibly built to defend Romans. But its true purpose was to assuage the fears of those it supposedly guarded, England’s Roman conquerors and the Britons they subdued. Even if the Picts had never invaded, the wall would have been a symbol of Roman might—and the fact that they did only feeds into the legend of a barrier that’s long since become obsolete.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The narrow streets & charming shops of Corbridge, Northumberland

#shop windows#Corbridge#Northumberland#Hadrian's Wall#English villages#northern England#historic#quaint#autumn

89 notes

·

View notes