#Castor canadensis

Text

Piebald American beaver (Castor canadensis) [x]

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Wet Beast Wednesday!

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A pair of North American beavers (Castor canadensis) emerging from their den in Winneshiek County, Iowa, USA

by Larry Reis

#north american beaver#beavers#rodents#castor canadensis#castor#castoridae#rodentia#mammalia#chordata#wildlife: iowa#wildlife: usa

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

6月にきたとき全寝だったビーバー一家がめちゃくちゃ元気でよかった

全員うつってないかもだけど4きょうだいです

5月20日うまれなのでこのとき生後3ヶ月とすこし

@遊亀公園附属動物園

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Barred owl was perched on a post in Ottawa then flew straight towards me and landed in a tree beside me.

Taken By Mel Legge

#mel legge#photographer#canadian geographic#barred owl#owl#bird photography#ottawa#castor canadensis#winter#snow#nature

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

North American Beaver, dark eyed juncos, black capped chickadees

0 notes

Text

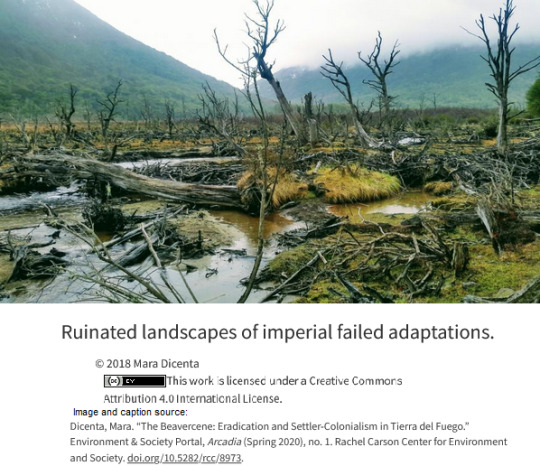

In 1946, Argentina introduced twenty beavers (Castor canadensis) to Tierra del Fuego (TdF) to promote the fur industry in a land deemed empty and sterile.

Beavers were brought from Canada by Tom Lamb, [...] known as Mr. North for having expanded the national frontier [...]. In the 1980s, local scientists [...] found that beavers were the main disturbers of sub-Antarctic forests. The fur industry had never been implemented in TdF and [...] beavers had expanded, crossed to Chile, and occupied most of the river streams. The Beavercene resulted in apocalyptic landscapes [...]: modified rivers, flooded lands, and dead native trees that, unlike the Canadian ones, are not resilient to flooding. [...]

At the end of the nineteenth century the state donated lands to Europeans who, in building their farms, also displaced and assassinated the indigenous inhabitants of TdF. With the settlers, livestock and plants also invaded the region, an “ecological imperialism” that displaced native populations. In doing this, eugenic and racializing knowledges mediated the human and nonhuman population politics of TdF.

---

In the 1940s, the Argentinian State nationalized these settlers’ capitals by redistributing their lands. [...] In 1946, the president of the rural association in TdF opened the yearly livestock [conference]: We, settlers and farmers of TdF have lived the evolution of this territory from the times of an absent State. [...] [T]hey allied with their introduced animals, like the Patagonian sheep or the Fuegian beaver. At a time when, after the two world wars, the category of race had become [somewhat] scientifically delegitimized, the enhancement and industrialization of animals enabled the continuation of racializing politics.

In 1946, during the same livestock ceremony in TdF, the military government claimed:

This ceremony represents the patria; it spreads the purification of our races … It is our desire to produce an even more purified and refined race to, directly, achieve the aggrandizement of Argentina.

---

The increasing entanglement between animal breeding and the nation helped to continue the underlying Darwinist logic embedded in population politics. Previous explicit desires to whiten the Argentinian race started to be actualized in other terms. [...]

Settlers had not only legitimated their belonging to TdF by othering the indigenous [people], [...] but also through the idea that indigenous communities had gone extinct after genocide and disease. At that time, the “myth of extinction” helped in the construction of a uniform nation based on erasing difference, as a geography textbook for school students, Historia y Geografía Argentinas, explained in 1952: If in 1852 there were 900,000 inhabitants divided in 90,000 whites, 585,000 mestizos, 90,000 [Indigenous people] and 135,000 [...] Black, a century later there was a 90% of white population out of 18,000,000 inhabitants. (357) [...] [S]tate statistics contributed to the erasure of non-white peoples through the magic of numbers: it is not that they had disappeared, but that they had been statistically exceeded [...]. However, repressed communities never fully disappear.

---

Text by: Mara Dicenta. "The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego". Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. [Image by Mara Dicenta, included in original article. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

River Ward & the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis)

Both look good staring off into the distance (look at those photos, the resemblance is uncanny)

Nice brown eye(s)

Soft brown hair

Associated with fresh bodies of water

Indigenous to North America

Handsome

Lorge (2nd largest rodent in the world)

Total hunks

Trees are no match for them

Absolutely huggable if you can catch one

Adorable as babies (I know we don't have any photos of River as a baby but I bet he was as adorable as a beaver kit)

Hardworking and industrious

Enjoys eating vegetables

Surprisingly good with their hands

Kind of awkward walking around on land

Excellent swimmers, very smooth when wet

Good shots (beavers slap their tails on the water to warn other beavers of danger, sounds a lot like a gun shot)

Really good at holding their breath (uh...)

Unable to completely stop the forces of nature/crime

But they keep trying to dam it all anyway

Gets along well with most other animals (unless they're trying to eat them)

Fur is very warm and well-insulated (look at their matching jackets)

Family oriented

Just wants to build a nice pond for their families to swim in

Enjoys playing basketball

Bad automobile drivers

Both like dad jokes

River Ward is a beaver. Thank you for attending my TedTalk 🌿🦫🏞️

#shitpost#cyberpunk 2077#river ward#beaver#ward wednesday#if river had a spirit animal it would be a beaver#yeah this is what i think about in my spare time#...#river ward and the north american beaver#in the spirit of dad jokes...

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Late Wet Beast Wednesday!

#wet beast wednesday#north american beaver#castor canadensis#beaver xenofiction ideas#otherkin#therian#biology#animal memes#⨺⃝

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wet Beast Wednesday: beavers

I love rodents; they're my favorite mammals. So today I'm combining rodents with the usual Wet Beast Wednesday to talk about beavers. These rodents are not only amphibious, they're engineers that play a major role in their ecosystems. Let's find out why you should appreciate beavers.

(Image ID: a beaver standing on dirt. It is a rotund, furry mammal with a large, blunt head. Its legs and eyes are small. Its tail is wide, flat, and hairless. It is wet. End ID)

There are two species of beaver: the North American beaver Castor canadensis and Eurasian beaver Castor fiber. The two species are so similar to each other in morphology and behavior that it took genetic testing to confirm that they are distinct species. Each species is divided into many subspecies, with a classified 25 for the North American beaver and 9 for the Eurasian beaver. Beavers are the second largest living rodents after the capybara. Adults have a body length of 80-120 cm (31-47 in), tail length of 25-50 cm (9.8-19.7 in) and usually weigh between 11 and 30 kg (24-66 lbs) but can reach up to 50 kg (110 lbs). Beavers are semiaquatic and have multiple adaptations for living in the water. The hind legs have webbed toes and are used to provide propulsion while swimming. The wide, flat, paddle-like tail is used as a rudder. Beaver fur is very thick, with 12,000 to 23,000 hairs per square centimeter and grows in multiple layers. The hair keeps the beaver warm and provides buoyancy while being thick enough to act as armor, protecting the beaver from predators. Beavers can hold their breath for up to 15 minutes, but most dives are shorter than that. While underwater, the beaver's heart rate is halved and blood is redirected to the brain and away from the extremities. The ears and nostrils can close underwater and the mouth can form a watertight seal. Being highly adapted for swimming, beavers are somewhat clumsy on land, but they can still move fast if needed. The front feet are very dextrous and can carry objects. Beavers can stand and move on their hind legs while holding things with their front feet. The tail helps provide stability while standing up. Like other rodents, beavers have an upper and lower pair of incisors that grow for their entire lives. The teeth need to be worn down by gnawing on objects and a beaver that can't gnaw can suffer from health problems as their incisors grow too big. Beaver teeth are coated with a layer of enamel that contains iron compounds, giving the incisors a characteristic orange color. The teeth grow outside the mouth and the beaver can close its lips while moving the teeth, letting it chew or pick thing up with its teeth underwater without getting water in its mouth. Unlike other rodents and pretty much every mammal, the beaver's excretory and reproductive tracts are merged into a single hole called the cloaca. Cloacas are common in reptiles, amphibians, etc, but having separate holes is a kay mammal trait. Beavers must have evolved back into having a cloaca. One hypothesis for why is that having a single hole reduced the surface area that can be exposed to the water, reducing the chance of infection. Males have a penis that extends from the cloaca when in use. Because of this, male and female beavers are virtually indistinguishable by sight if the penis is retracted. Staying downstairs, beavers have two sets of scent glands, anal glands and castor sacs. Both are used to produce scent chemicals that are used by beavers to mark their territory and identify each other. The anal glands also produce an oily substances that beaver groom into their fur to help waterproof it. The castor sacs produce a substance called castoreum and are attached to the urethra. Ancient people often thought that the castor sacs were testicles and that female beavers were actually hermaphrodites.

(Image ID: a beaver seen from the front on some rocks by the water's edge. It is dragging a long log in its mouth. Its top incisors are visible and orange. End ID)

The North American beaver is found in most of Canada and the United States, as well as northern Mexico while the Eurasian beaver's natural range has been considerably reduced from what it once was. They now live in portions of western, central, and eastern Europe, west Russia, and Scandinavia, with isolated populations in Mongolia and northwest China. Beavers live in freshwater (and occasionally brackish water) streams and lakes. They are nocturnal and crepuscular, active most commonly between dusk and dawn. Beavers are generalist herbivores, eating a variety of leaves, stems, shoots, roots, and bark. They prefer herby food in summer and woody food in winter. Beavers form stores of food underwater for the winter. Their digestive systems have an enlarged portion of the intestine called a caecum that helps digest the cellulose form all the plants and wood they eat. Their feces has been reported to have sawdust in it. Beavers are territorial and mark their territory with smell using secretions from their anal and castor glands that are placed onto piles of rock and mud they build. beavers defend their territories fiercely and will get into fights with others trying to move into their territory. Beavers who live in neighboring territories will gradually grow less aggressive toward each other and they become used to each other's scent. This is called the dear enemy effect and is seen in other territorial species. Beavers communicate using a variety of noises including whines and growls. A common behavior is slapping the tail against the surface of the water, which is used to alert other beavers to danger.

(Image ID: a beaver swimming underwater. Its body is strengthened out and streamlines. Its front legs are tucked under its chin. The hind legs are being used for swimming. The tail is out of frame. There are rocks and logs in the background. End ID)

Beavers require deep and still water to build their homes, but they aren't satisfied just looking for lakes to live in. No, these little entrepreneurs will make the conditions they need by damming streams. I will devote a whole section below to beaver damming and its impacts on the environment. Aside from dams, beavers also build lodges, which are their homes. Building these structures requires material and beavers use wood, mud, and rocks. To get the wood, they use their incisors and powerful teeth to chew through trees and branches. Famously, a beaver can take down a large tree in under a day. Lodges take a while to build, and until it is ready, beavers live in simple burrows on the water's edge. There are two types of lodges: bank lodges and open-water lodges. Bank lodges are burrows along the water's edge covered in sticks and are more common with Eurasian beavers. The more famous open-water lodges are built away from the shore. A pile of sticks forms a platform that is covered with a dome. The dome reaches above the water and is made of sticks and rocks held together with mud. Inside the dome but above the water is an open cavity filled with air. This is called the living space and is (as the name suggests) where the beavers live. The only above-water opening in the living space is an air hole built in the very top. The other entrances are underwater, meaning that beavers can only enter and leave by swimming. This provides good protection from predators, most of whom wouldn't be able to swim into the living space, as wells as insulation to keep the living space warm in winter. Beavers live in familial groups usually consisting of a pair of parents and up to eight children. Family members use the scent of their anal glands to identify each other and will body through grooming each other and play-fighting. The parents are monogamous, but will seek out new mates if they lose theirs. Mating occurs in late December to mid January when the female goes into heat. Up to four pups are born three to four months later. Beavers are born furry and with open eyes and can digest solid food after a week, but usually nurse for up to three months. Beaver milk is more fatty than the milk of other rodents. Beaver offspring will stay with their parents for two years before becoming independent and a family can have two generations of offspring at a time. The largest families need to build multiple lodges. The offspring, called kits, will stay in the lodge for their first one to two months and will start assisting the family with construction of dams and lodges at a year old. They reach sexual maturity between one and three years of age and can live for up to ten years in the wild. Beavers that become independent will travel away from their parent's pond to find a new stream or pond to settle in. This is the time most beavers meet their future mates and the pair will travel together in search of their new home. Beavers will stay in the same territory unless poor conditions force them to leave and find a new home.

(Image ID: A beaver in the Minnesota Zoo with four kits. They are in an artifical lodge with stone walls and star and sticks on the ground. The kits are miniature versions of the adult. End ID.)

(Image ID: an artistic depiction of a beaver lodge with a cutaway to show the interior. It is a large pile of branches with a chamber inside partly submerged in the water. The chamber is connected to the outside by two tunnels the open underwater. There are two adult beavers outside the lodge and three juveniles inside. End ID. Source)

The most famous feature of beaver behavior is their dams. By damming streams, beavers create the large and still ponds they need to build their dams. Beavers that live in pre-existing ponds or lakes that are deep enough for their lodge entrances to be underwater don't need to build dams. To start, thy will dig canals to reduce the flow of the stream, then drive large logs and branches into the mud of the stream bottom to form a base. The dam is then filled in with rocks, branches, shrubs, mud, and anything else the beaver can get its paws on. Beavers can pull or carry objects up to their weight and will build canals and use mud slicks to pull larger logs. Dam complexes can cover acres of territory and the canals beavers dig dig to divert water and help move logs around can be over half a kilometer (1,600 ft) long. The largest dam in the world is in Alberta, Canada's Wood Buffalo National Park and is 775 meters (2,543 ft) long and growing. It was formed of different dams that were combined. Beavers are one of the best examples of ecosystem engineers, species that modify their habitats. They are also a keystone species that are vital in wetland areas of their native range. Dams expand wetlands and reshape the stream environment in ways that typically benefit the local ecosystem. There are some negative impact of beaver dams, including impeding fish migration, increasing silt upstream of the dam, low oxygen levels in the created ponds, and harming species that require fast flowing water. However, the positive impacts of the dams are many and varied. The dams create new ponds that provide habitat for many species that require deeper or slower water, including many aquatic insect larvae, worms, and mussels. These ponds are also ideal spawning locations for many fish and amphibian species, especially salmon and trout that can leap over the dams. Indeed, beaver dams are a huge boon to salmon spawning. The ponds also raise the local water tables and help prevent drought. The areas in and around ponds see a large increase in plant species diversity that encourages local grazing animals and migratory species to visit. Because the areas around beaver ponds are so wet, they act as natural fire breaks, helping mitigate the damage from fires. The dams also help prevent floods downstream by slowing the amount of water that passes, thus helping prevent erosion. The dams act like sieves, filtering out silt, debris, excess nitrogen, and pesticides and other chemicals that get into the water. Bacteria living in the dams break down cellulose in plant matter and release nitrogen gas into the atmosphere. On the downside, beavers have been extending their range north as the arctic warms and their ponds are melting permafrost, which releases methane into the atmosphere.

(Image ID: a beaver in a forest environment gnawing a tree. The tree trunk is slightly thicker around than the beaver. The Beaver is chewing at one side of the tree while the other side is already chewed, resulting in an hourglass shape. End ID)

(Image ID: two beavers sitting on top of their dam and working on building it. One beaver is gnawing on a log while the other one is carrying a bundle of roots in its mouth. End ID)

(Image ID: a beaver dam seen from above. The dam is a large pile of sticks, longs, rocks, and mud that stretches across a stream. The water level on one side of the dam is significantly higher than on the other side. End ID.)

Both species of beaver as currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, meaning they are not at risk of extinction. This was not always the case. Beavers have historically been heavily trapped for their meat, fur, and castoreum. The castoreum was used in many forms of medicine. Nowadays it isn't used anymore except in homeopathy and other forms of quackery. The fur trade vastly reduced beaver populations and it was only due to new laws and conservation efforts that the two species were saved from extinction. Since then conservation efforts have largely revolved around trapping beavers and reintroducing them to new areas. Probably the most famous example of this is the 1948 beaver drop, when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game dropped beavers in crates from planes, where they parachuted to the ground and were released. Despite how silly this sounds, it had a much higher survival rate than other relocation methods. Only one of the 76 beavers died due to forcing its way out of the crate during the drop and falling to its death. Beavers can damage infrastructure by damming streams near human activity and can damage trees people want to keep alive. There are ways of mitigating this. Pipes can be used to keep the water levels of the ponds from getting too high and fences or other deterrents around trees keep the beavers from cutting them down. If the beavers are causing too much of a problem, trapping and relocating them can help. On the other hand, sometimes environmental managers trying to attract beavers will make artificial beaver dams to try to entice beavers to adopt a stream. This is sometimes done in streams with too much erosion or water that flows too fast for beavers to settle. The artificial dams start the work and set things up for beavers either relocated to the stream or that pass by and settle down. Beavers are used as symbols of hard work, industry, and families. The beaver is the national animal of Canada. If Canada appreciates the beaver, shouldn't you too?

(Image ID: a group of three beavers being released from a crate. End ID)

youtube

(Video ID: archive footage of the 1948 beaver drop. End ID)

#wet beast wednesday#beaver#rodent#mammal#beaver dam#beaver lodge#biology#zoology#ecology#freshwater ecology#animal facts#long post#educational#image described#Youtube

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

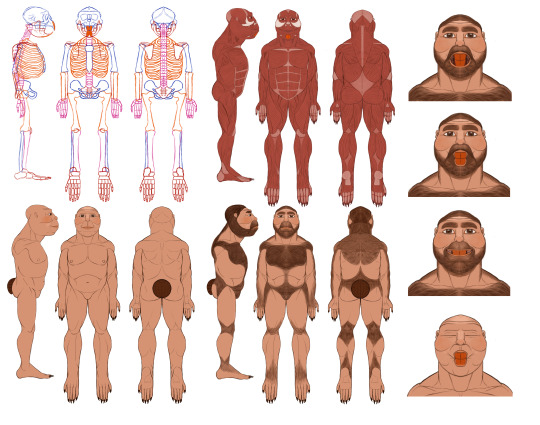

An introduction to Castor erectus:

Castor erectus, common name "Mountain Dwarf" is member of Castorimorphia, a suborder of rodents that consists of the superfamilies Castoroidea, (Modern Beavers) and Geomyoidea (Kangaroo Rats).

In our current timeline, the genus Castor has only two extant members, Castor canadensis, common name "North American Beaver", and Castor fiber, common name "Eurasian Beaver".

Castor erectus offers an alternate evolutionary history where Beavers evolved to fill human-like niches. Their look and culture are heavily inspired by the stories of Dwarves as told in fantasy epics such as Lord of the Rings, as well as stories of dwarves from Germanic folklore. Their design is meant to be unique enough to offer an interesting history and flavor for Dwarves, while still being familiar enough to be recognizable as Dwarves.

Castor erectus stands at an average of 4'5", with specimens varying in height by +/- 4 inches (for healthy adults.) Female dwarves are on average 3 inches shorter than their male counterparts.

Castor erectus shows little to no sexual dimorphism. (You may have seen my previous sexual dimorphism model, this was based on my incorrect assumption that strong sexual dimorphism was present across most mammals.) Modern beavers lack external genitalia, a trait that is present in Castor erectus, which makes it difficult to distinguish a Dwarf's sex. Members of the species can easily distinguish the sex of other members through smell, though their culture does not place a heavy emphasis on gender. The Dwarven language lacks gendered pronouns, and sexuality among Dwarves is incredibly fluid. Same sex pairings can be a helpful evolutionary tool, allowing communal-living social species to meet the social and sexual needs of its' members, without increasing population of their colony to an unsustainable size.

Dwarves typically live in large colonies constructed in and around mountain cave systems. These structures are known as Lodges, which are an evolved form of modern beaver habitats. The construction of these lodges generally begins with the construction of a large cistern, and a canal below the snowcap of their home mountain which diverts runoff into the cistern for collection. They use this collected water to fuel primitive aquaponics and hydroponics systems in their lodges. Dwarves are often separated into small familial groups, but it is not uncommon for distantly related groups to merge into a single colony to control resources and water.

In the future, I will be posting more illustrations and writings detailing Dwarven Culture, as well as exploring their evolutionary history through extinct relatives. If you have any questions about their culture or anatomy in the mean time, feel free to ask! Any amount of feedback helps to flesh them out and answer questions I might not have otherwise thought of.

#dwarves#dwarf#speculative anatomy#speculative zoology#speculative biology#spec bio#specbio#fantasy art#evolution#anatomy#digital art

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

My fic for Forduary week 1: Childhood and school years!

This one is an HDM AU-- Ford's daemon settles and he's not that happy about it. Takes place in the same verse as this ficlet I posted a good while ago. (Short version of an HDM au: people's souls live outside their bodies in the shapes of animals. Kids' daemons can shapeshift but they settle into a permanent form during puberty.)

Ford settles first, not so long after his and Stanley’s Bar Mitzvah. He’s almost relieved. He kind of didn’t want Stan to be first, but he wouldn’t admit it to Stanley. It’s just that people expect Ford to be the more responsible one, and if his daemon’s settled, it’ll get people to take him more seriously. Stan wouldn’t understand that; his feelings would be hurt if he thought that Ford thought he was better than Stan. Not that he thinks that! Stan is the best. The best brother and friend and the bravest and toughest and most fun and lots of other stuff, besides. But he’s not very responsible, and Ford can’t even quite admit it to himself that he loves being seen as responsible when compared to Stan.

So Ford should be really glad that Elisheba’s settled. They’re the perfect age for it, right smack dab in the middle of the bell curve– they’re normal about something for once. It’s just that he can’t understand her form. They used to fantasize about what she’d become, like all kids probably do. Ellie loved to be an arctic tern– a bird that’s always migrating! And they can sleep while they’re flying! That would have been so cool! And she was a green iguana a lot, and even a Tasmanian tiger! Almost nobody had an extinct animal for a daemon– that would have been really impressive. And if it set them apart, made them even more different than their peers, who cared? Ford could take it. He’d had everyone making fun of him for his hands his whole life, he could stand it if people thought his daemon was too different or strange. But Ellie’s form, the thing she’s going to be forever, well. He’s just not sure about it.

Castor canadensis, North American beaver, isn’t really… him. Right? She isn’t anything particularly interesting or special. Nobody brilliant or noteworthy ever had a beaver for a daemon. No inventors or explorers or anything. In movies, do hard-boiled detectives or chiseled leading men have beavers for daemons? No, they don’t. The only beaver daemons in movies and on TV are laundresses or scolding mothers.

The only person Ford’s ever seen in real life with a beaver daemon is a mechanic. A Catholic mechanic with a beaver daemon and arthritis.

“I don’t really get it, Ellie,” says Elisabeth, Stan’s daemon. She’s on the floor of their room next to Elisheba, a red fox at the moment, sniffing at her. “Is being a beaver really that great?” She becomes a perfect copy of Elisheba and loudly smacks her tail against the living room floor. “Oh, that’s pretty fun!” They both laugh and slap the floor until they hear a distant shout from Dad.

“Okay, I guess the tail-slapping is alright,” Stan tells him skeptically, “but not that great. You could just drop one of your books on the floor and get the same effect.” Lisa pops into the air as a hornet and buzzes teasingly around Ford’s head.

“You’re just jealous,” he laughs as he bats Lisa away, wishing that he didn’t agree with Stanley.

-

Ford kicks his feet against the hull of the Stan o’ War. He’s holding a schoolbook, but staring out at the ocean. He should be doing his homework while he waits for Stan to get out of detention, but instead he’s brooding. Elisheba sighs behind him, and Ford frowns. He doesn’t want to turn around and see her squat little form, her dopey face, her long orange teeth. It’s been two days since she settled, and he still doesn’t know how to feel about it.

“You’re just going to have to deal with it,” she says resentfully, breaking their hours-long silence.

“I don’t have to deal with anything. I’m fine. I’m happy! It’s good that we’ve settled,” Ford tells her, feeling his jaw settle into a mulish expression. He can hear her clawed forepaws dig into the planks of the deck. He rounds on her, ready to scold her for clawing up their dilapidated wreck, but he looks straight into her eyes and finds he can’t get a word out.

Elisheba stares back at him, burning with the resentment and disappointment that feels too big for Ford’s chest to hold. Of course she feels the same, how could she not? She’s him, the biggest, truest, most important part of himself. That's the problem.

“I just didn’t think that we’d… be like this.” He feels ashamed to say it to her, even if they both think it. It feels like some kind of betrayal.

“We are who we are!” Ellie slaps her tail on the deck for emphasis. “This form just feels right, what does it matter exactly what I am if we’re still ourself?”

“Hey, break it up!” Lisa flaps up over the side of the Stan o’ War in her largest avian form, a brown pelican. She alights heavily on the deck next to Ellie, reaching a wing out over her as if to shelter her from harsh sunlight. “Man, this is why you need me around, Sixer,” she says lightly. “You get yourself into trouble when you think too much.”

Stan struggles up onto the deck, flopping down with an oof. He sits up, taking in Ford, standing facing his daemon and Stan’s, fists clenched. Ford knows he must be bright red, and hopes Stan thinks it’s all anger.

Stan, who is sometimes so able to be cool under pressure, shrugs off his heavy backpack and his jacket, leaving them behind him in a heap on the deck. The wind flutters through his and Ford’s hair, and ruffles Elisabeth’s feathers.

“Hi, Stanley. How was detention?” Ford mumbles, hoping to change the subject before Stan can even start it.

“Fired six spitballs onto Miss Lackson’s dress without her noticing even once!” Stan says proudly. Lisa preens. “And I even got some homework done, so you don’t have to do it all,” he adds impressively.

Ellie laughs. “My hero,” she teases, and nudges Lisa so hard she has to open her wings so as not to fall over. Ford snickers.

“You should be grateful!” Stan insists, all overblown indignation. Ford knows it’s just to make him laugh, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. “Here I am slaving away, learning crap outta books that I’m never gonna use just so you don’t have to do my homework, and you’re here talking to yourself like a crazy kid!”

“I’m not crazy, you’re craz– hey!” Ford grabs for Elisheba as Lisa opens her beak wide, trying to fit Ford’s daemon into her cavernous mouth. Before Ford can grab Ellie, she hisses viciously, flashing her long orange teeth at her brother. With a whoop of delight, Lisa turns into one of her favorite forms, a caiman, and snaps her jaws right back at Ellie.

“Hah!” Stan flings himself at Ford, grabbing him in a headlock while he’s distracted by Lisa’s many sharp teeth trying to take a bite out of Elisheba’s new, permanent tail.

“Hey, I’m planning on keeping that tail, Lisa!” Elisheba yelps, naturally echoing Ford’s thought.

“Ow! Stanley!” Stan’s knuckles dig into Ford’s scalp. Ford flails his hands blindly in the direction of Stan’s body, completely forgetting anything he might have learned in boxing.

“Say uncle, Poindexter!” Stan demands gleefully. Ford raises his foot to kick Stan in the shin– it’s a dirty move, which Stan should approve of–but Stan gasps and lets him go before Ford goes for it.

As he straightens up, Ford has a brief impression of Elisheba between Lisa’s shoulders, claws gripping crocodilian hide and incisors digging into her head, perilously close to Lisa’s eye. Lisa turns into a dingo and shakes Ellie off her back with a slight yelp. She bounds over to Stan.

“Wow, jeez, ease up, Fangs,” Lisa complains, as Stan cradles her head in his hands, inspecting it for damage.

“Eh, don’t be such a baby, Ellie ain’t gonna blind us,” he tells her. Still, he strokes her ears gently.

“Yeah, I had everything under control,” Ellie says, panting. “When have we ever blinded you before? The trend would suggest that we will continue not to gouge out any of your body parts.”

Ford, grinning, leans down to pick Ellie up. She’s heavy– must be almost forty pounds. They haven't weighed her yet, which they should. And they need to find out how fast she can run– can she even run? He doesn’t know, but he’ll find out.

“That was pretty good, Ellie!” Stan, satisfied that his soul will survive, reaches out and ruffles the fur on the back of Ellie’s neck.

“Stan!” Ford tugs her away from his reach, embarrassed. They’re getting too old to touch each other’s daemons like they did when they were small. That kind of thing is only for babies and really little kids, which they definitely aren’t. “You shouldn’t do that!”

Stan goes on like Ford hasn’t spoken. “You can fight pretty good in that form, but what else can I expect from a guy with metal teeth?”

“What?” Ford laughs.

“Yeah! Stan opens his own mouth and points inside as if that explains anything. “Beavers got iron in their teeth, that’s how come they’re orange! It’s like rust!”

“How do you know that?” Ford asks suspiciously.

“I know stuff! I know everything! Specially everything about you,” Stan insists, as Lisa wags her tail charmingly.

“Come on!” Ford punches Stan in the shoulder, grinning at his brother. “You don’t just know that magically! Unless…” Ford scratches his chin, wincing as he scrapes a pimple with his nail.

“Don’t bring up aliens,” Lisa groans.

“It’s a known fact that the protective anti-alien-scanning machinery the government uses to protect national secrets interferes with human brainwaves!” Ford crosses his arms, eyeing Stan suspiciously. “Have you been having headaches? Dreaming about nuclear launch codes?”

Stan groans. “God, Ford, you’re the biggest nerd! I read it in a book, okay?” Stan slumps over to his backpack, Ford following curiously. He pulls two thick books from it, turning and offering them to Stanford. “Here. I figured, you know, you’re a huge geek, you’d wanna read up on Ellie’s form and stuff.”

Ford sets Ellie down, then kneels so she can look at the covers with him. Rodents of North America says one, and Beaver: America’s Engineer says the other.

It’s so strange to feel so many ways at once. It’s surprising, and not, that Stan would do this; Stan would do anything for him, and Ford knows that. But that Stan would do this, specifically, go to the library– the city library! Those are city library stickers on the spines, they aren’t even from the school! All just for him, because Stan is his brother and the only person in Ford’s corner. He grateful, really. It's a nice thing for Stan to do, but there’s a little part of him that’s annoyed that Stan could read him so well. Shouldn’t he get to have some feelings that are private? Oh well. Ford shoves that down, and tries to just be grateful.

Made nervous by Ford’s silence, Lisa says “We didn’t look that close at ‘em but there’s some cool stuff in there. About your fur and your teeth and all the stuff beavers can build. And you’re gonna be a real good swimmer! That’ll be handy if we’re ever lost at sea!” She wags her tail vigorously and nuzzles Ellie, who presses herself close in response.

“Yeah, yeah,” Stan nudges the daemons apart with his foot, as uncomfortable as Ford is with all the mushy stuff. “Look, point is… uh.” He scratches at the back of his head.

Ford jumps in to save them both from the awkwardness. “I get it, Stan, really.” He hugs the books to his chest. He’ll say it, partly because he means it, and partly because he should probably mean it more than he does.

“Thank you.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the first time in four centuries, it’s good to be a beaver. Long persecuted for their pelts and reviled as pests, the dam-building rodents are today hailed by scientists as ecological saviors. Their ponds and wetlands store water in the face of drought, filter out pollutants, furnish habitat for endangered species, and fight wildfires. In California, Castor canadensis is so prized that the state recently committed millions to its restoration.

While beavers’ benefits are indisputable, however, our knowledge remains riddled with gaps. We don’t know how many are out there, or which direction their populations are trending, or which watersheds most desperately need a beaver infusion. Few states have systematically surveyed them; moreover, many beaver ponds are tucked into remote streams far from human settlements, where they’re near-impossible to count. “There’s so much we don’t understand about beavers, in part because we don’t have a baseline of where they are,” says Emily Fairfax, a beaver researcher at the University of Minnesota.

But that’s starting to change. Over the past several years, a team of beaver scientists and Google engineers have been teaching an algorithm to spot the rodents’ infrastructure on satellite images. Their creation has the potential to transform our understanding of these paddle-tailed engineers—and help climate-stressed states like California aid their comeback. And while the model hasn’t yet gone public, researchers are already salivating over its potential. “All of our efforts in the state should be taking advantage of this powerful mapping tool,” says Kristen Wilson, the lead forest scientist at the conservation organization the Nature Conservancy. “It’s really exciting.”

The beaver-mapping model is the brainchild of Eddie Corwin, a former member of Google’s real-estate sustainability group. Around 2018, Corwin began to contemplate how his company might become a better steward of water, particularly the many coastal creeks that run past its Bay Area offices. In the course of his research, Corwin read Water: A Natural History, by an author aptly named Alice Outwater. One chapter dealt with beavers, whose bountiful wetlands, Outwater wrote, “can hold millions of gallons of water” and “reduce flooding and erosion downstream.” Corwin, captivated, devoured other beaver books and articles, and soon started proselytizing to his friend Dan Ackerstein, a sustainability consultant who works with Google. “We both fell in love with beavers,” Corwin says.

Corwin’s beaver obsession met a receptive corporate culture. Google’s employees are famously encouraged to devote time to passion projects, the policy that produced Gmail; Corwin decided his passion was beavers. But how best to assist the buck-toothed architects? Corwin knew that beaver infrastructure—their sinuous dams, sprawling ponds, and spidery canals—is often so epic it can be seen from space. In 2010, a Canadian researcher discovered the world’s longest beaver dam, a stick-and-mud bulwark that stretches more than a half-mile across an Alberta park, by perusing Google Earth. Corwin and Ackerstein began to wonder whether they could contribute to beaver research by training a machine-learning algorithm to automatically detect beaver dams and ponds on satellite imagery—not one by one, but thousands at a time, across the surface of an entire state.

After discussing the concept with Google’s engineers and programmers, Corwin and Ackerstein decided it was technically feasible. They reached out next to Fairfax, who’d gained renown for a landmark 2020 study showing that beaver ponds provide damp, fire-proof refuges in which other species can shelter during wildfires. In some cases, Fairfax found, beaver wetlands even stopped blazes in their tracks. The critters were such talented firefighters that she’d half-jokingly proposed that the US Forest Service change its mammal mascot—farewell, Smoky Bear, and hello, Smoky Beaver.

Fairfax was enthusiastic about the pond-mapping idea. She and her students already used Google Earth to find beaver dams to study within burned areas. But it was a laborious process, one that demanded endless hours of tracing alpine streams across screens in search of the bulbous signature of a beaver pond. An automated beaver-finding tool, she says, could “increase the number of fires I can analyze by an order of magnitude.”

With Fairfax’s blessing, Corwin, Ackerstein, and a team of programmers set about creating their model. The task, they decided, was best suited to a convolutional neural network, a type of algorithm that essentially tries to figure out whether a given chunk of geospatial data includes a particular object—whether a stretch of mountain stream contains a beaver dam, say. Fairfax and some obliging beaverologists from Utah State University submitted thousands of coordinates for confirmed dams, ponds, and canals, which the Googlers matched up with their own high-resolution images to teach the model to recognize the distinctive appearance of beaverworks. The team also fed the algorithm negative data—images of beaverless streams and wetlands—so that it would know what it wasn’t looking for. They dubbed their model the Earth Engine Automated Geospatial Elements Recognition, or EEAGER—yes, as in “eager beaver.”

Training EEAGER to pick out beaver ponds wasn’t easy. The American West was rife with human-built features that seemed practically designed to fool a beaver-seeking model. Curving roads reminded EEAGER of winding dams; the edges of man-made reservoirs registered as beaver-built ponds. Most confounding, weirdly, were neighborhood cul-de-sacs, whose asphalt circles, surrounded by gray strips of sidewalk, bore an uncanny resemblance to a beaver pond fringed by a dam. “I don’t think anybody anticipated that suburban America was full of what a computer would think were beaver dams,” Ackerstein says.

As the researchers pumped more data into EEAGER, it got better at distinguishing beaver ponds from impostors. In May 2023, the Google team, along with beaver researchers Fairfax, Joe Wheaton, and Wally Macfarlane, published a paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research Biogeosciences demonstrating the model’s efficacy. The group fed EEAGER more than 13,000 landscape images with beaver dams from seven western states, along with some 56,000 dam-less locations. The model categorized the landscape accurately—beaver dammed or not—98.5 percent of the time.

That statistic, granted, oversells EEAGER’s perfection. The Google team opted to make the model fairly liberal, meaning that, when it predicts whether or not a pixel of satellite imagery contains a beaver dam, it’s more likely to err on the side of spitting out a false positive. EEAGER still requires a human to check its answers, in other words—but it can dramatically expedite the work of scientists like Fairfax by pointing them to thousands of probable beaver sites.

“We’re not going to replace the expertise of biologists,” Ackerstein says. “But the model’s success is making human identification much more efficient.”

According to Fairfax, EEAGER’s use cases are many. The model could be used to estimate beaver numbers, monitor population trends, and calculate beaver-provided ecosystem services like water storage and fire prevention. It could help states figure out where to reintroduce beavers, where to target stream and wetland restoration, and where to create conservation areas. It could allow researchers to track beavers’ spread in the Arctic as the rodents move north with climate change; or their movements in South America, where beavers were introduced in the 1940s and have since proliferated. “We literally cannot handle all the requests we’re getting,” says Fairfax, who serves as EEAGER’s scientific adviser.

The algorithm’s most promising application might be in California. The Golden State has a tortured relationship with beavers: For decades, the state generally denied that the species was native, the byproduct of an industrial-scale fur trade that wiped beavers from the West Coast before biologists could properly survey them. Although recent historical research proved that beavers belong virtually everywhere in California, many water managers and farmers still perceive them as nuisances, and frequently have them killed for plugging up road culverts and meddling with irrigation infrastructure.

Yet those deeply entrenched attitudes are changing. After all, no state is in more dire need of beavers’ water-storage services than flammable, drought-stricken, flood-prone California. In recent years, thanks to tireless lobbying by a campaign called Bring Back the Beaver, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has begun to overhaul its outdated beaver policies. In 2022, the state budgeted more than $1.5 million for beaver restoration, and announced it would hire five scientists to study and support the rodents. It also revised its official approach to beaver conflict to prioritize coexistence over lethal trapping. And, this fall, the wildlife department relocated a family of seven beavers onto the ancestral lands of the Mountain Maidu people—the state’s first beaver release in almost 75 years.

It’s only appropriate, then, that California is where EEAGER is going to get its first major test. The Nature Conservancy and Google plan to run the model across the state sometime in 2024, a comprehensive search for every last beaver dam and pond. That should give the state’s wildlife department a good sense of where its beavers are living, roughly how many it has, and where it could use more. The model will also provide California with solid baseline data against which it can compare future populations, to see whether its new policies are helping beavers recover. “When you have imagery that’s repeated frequently, that gives you the opportunity to understand change through time,” says the Conservancy’s Kristen Wilson.

What’s next for EEAGER after its California trial? The main thing, Ackerstein says, is to train it to identify beaverworks in new places. (Although beaver dams and ponds present as fairly similar in every state, the model also relies on context clues from the surrounding landscape, and a sagebrush plateau in Wyoming looks very different from a deciduous forest in Massachusetts.) The team also has to figure out EEAGER’s long-term fate: Will it remain a tool hosted by Google? Spin off into a stand-alone product? Become a service operated by a university or nonprofit?

“That’s the challenge for the future—how do we make this more universally accessible and usable?” Corwin says. The beaver revolution may not be televised, but it will definitely be documented by satellite.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

🟪 ANIMAL OF THE DAY: north american beaver. Castor canadensis. they really do make Dams and humans use their castor (musk) to create some Perfumes. they like to brag about their STEM degrees but wonder why they can't get Hoes (real)

19 notes

·

View notes