#ACT Michael Wollny Joachim Kühn

Text

Geschafft. Und schwimmend nun - ACT sei gedankt - in Duos von Wollny und Kühn. Wenn auch der Schädel Schillers neu eine Rolle spielt.

Hat jetzt doch länger gedauert, als ich erst glaubte. Ich hatte sogar gedacht, früher fertig zu werden als sonst, weil ich Elster ja schon kannte. Aber die dortigen online-Formulare verändern sich von Jahr zu Jahr, wie mir ein Mitarbeiter an der Hotline, sagte; nicht grundlegend zwar, aber doch spürbar. Und wo ich nach Inhalten buchführe – “Reisen”, “Bankkosten” “Bewirtungen”, “Büro”,…

View On WordPress

#Abschreckungsideologie Atombombe Antisemitismus#ACT Michael Wollny Joachim Kühn#Alban Herbst Rumiz-Rezension#Alban Nikolai Herbst Arbeitsjournal#Alban Nikolai Herbst Arbeitswohnung#Arbeitswohnung Dunckerstraße#Arbeitswohnung Jungfernrebe#Arco Verlag Briefe nach Triest#Bałdych Możdżer#Briefe nach Triest Alban Herbst#Bruno Lampe Helmut Schulze#Bruno Lampe Parallalie#Christian Krachts#Christopher Ecker#Elfenbein Verlag Anderswelt#Finanzamt Elster#Junge Welt AfD#Jungfernrebe Dunckerstraße#Parallalie Dschungel.Anderswelt#Schillers Schädel#Steuererklärung Alban Herbst#Thetis.Anderswelt#Triestbriefe Roman#Wohlklangskitsch#Wollny Kühn Duo

0 notes

Text

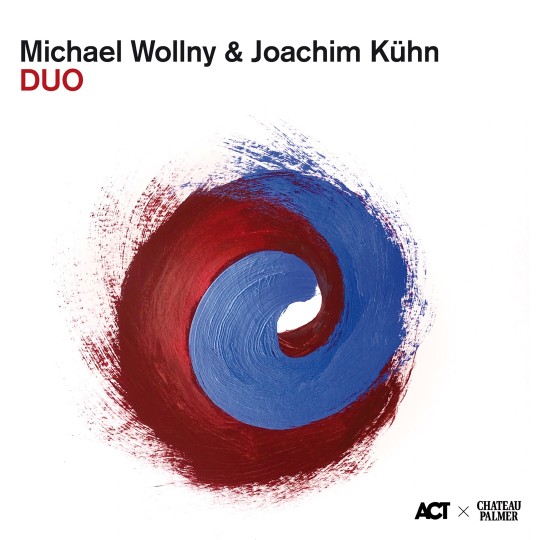

Michael Wollny & Joachim Kühn „Duo”

ACT Music, 2024

Pierwsze nagrania duetu Kühn / Wollny ukazały się w październiku 2008 roku – był to album “Piano Works IX: Live At Schloss Elmau”. 15 lat później, otrzymujemy “Duo” – wydawnictwo dokumentujące spotkanie dwóch wybitnych pianistów w Alte Oper we Frankfurcie.

Płyta zarejestrowana została podczas koncertu 23 stycznia 2023 roku (niemal dokładnie rok przed premierą).…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Audio

Rainer Böhm

Hýdor (piano works XII)

ACT, 2018

Rainer Böhm / piano

“ACT seems to be on a mission to introduce the world to Europe's rising new jazz-classical pianists,” the UK’s leading jazz critic John Fordham of the Guardian has noted. And jazz for piano has indeed always been part of ACT's DNA. The label’s roster includes pianists who have achieved international renown such as Joachim Kühn, Esbjörn Svensson and Michael Wollny; and more recently the Austrian David Helbock has started to be recognized as the major talent he clearly is. Siggi Loch started the dedicated album series “Piano Works” to present the finest in solo piano playing, and Rainer Böhm with his album “hýdōr” becomes the latest pianist to enter this pantheon.

Born in Ravensburg in Southern Germany in 1977 and now based in Cologne, Böhm is considered by critics to be one of the country’s outstanding jazz pianists, yet among the wider public he has not reached the level of recognition he deserves. He has made his mark through some excellent projects – with saxophonists Johannes Enders and Lutz Häfner, and trumpeter Axel Schlosser, for example. In 2016 with drummer Bastian Jütte’s quartet he won the award which is widely held to be the most important in German jazz, the New German Jazz Prize – and he won the Soloist Prize as well. He teaches at the conservatoires in Nuremberg and Mannheim, where he is one of their youngest professors.

Böhm is also known as a long-standing member of the trio of Germany’s pre-eminent bassist, Dieter Ilg. The success and the impact that this group has achieved are at least in part attributable to Böhm’s remarkable piano playing, notably in its jazz adaptations of the greats of classical music – Verdi, Wagner, Beethoven and Bach. Indeed, the concept of crossing such frontiers is at the core of Böhm's musical identity, and is to be found in its purest form on “hýdōr”. Böhm is one of those genre-defiers for whom classical music and jazz are not in opposition to each other, but perfectly complementary polarities situated around a central task: how to convey emotions through music.

The way Böhm has now risen to this challenge as a solo pianist is magnificent. He is able to rely on a stupendous technique: seldom can such deft alternation of left and right hands in melody and chordal accompaniment been heard as in the two parts of Böhm's “Bass Study”. Böhm also uses chromaticism in a highly original way on “hýdōr”, not only in pieces such as “Querstand” (where it is to be expected, the title, is the German for the musical term ‘false relation’), but also on “Terzen” (thirds) in which chromatic twists have a captivating way of subverting the melodic sweetness. In “Expansion And Reduction” Böhm achieves exactly what the title promises: wonderful harmonic resolutions, strongly rhythmic playing, and contrasting aggressive syncopation with a calm steady pulse as an underlying ostinato.

All of this allows him to exploit the deepest well of his creativity, which is his inexhaustible melodic inventiveness. Again and again, irresistible melodies emerge; they can be ethereal miniatures reminiscent of Grieg as in the title track “hýdōr”, heavily romantic as in the agitated tune “Catalyst”, skittish as in the bebop-style “Thumb Up, Broken Toe”, or gently lyrical as in “Hypo”. Another kind of fascination comes from a rhythmically superimposed melody in “Badi Bada” – which dances carefree over clusters in the left hand à la Philip Glass.

The reason that Böhm's playing, compositions and improvisations are so affecting is that they are so subtle. He prefers allusion to heart-on-sleeve and favours themes which are pared-down (and which can also change in surprising ways) in place of over-obvious motifs. They draw the listener deep into a world which is always tinged with melancholy. “That’s probably in line with my character,” he reflects. In “hýdōr” Böhm has impressively joined the ranks of the great piano romantics. His highly individual voice makes a new and distinguished addition to the “Piano Works” series.

in www.actmusic.com

0 notes

Audio

Michael Wollny & Vincent Peirani

Tandem

ACT Music, 2016

Michael Wooly, piano

Vincent Peirani, accordeon

German pianist Michael Wollny and French accordionist Vincent Peirani bring jazz, classical, folk and improvised music together in this fine recording- their first as a duo. ‘We prepared and arranged some of the pieces with great care, whereas we left others very free and completely open to the spontaneous ideas,’ says Wollny: their response to each other is so intuitive, it’s not always easy to tell which is which.

They open with Song Yet Untitled, by Swiss singer Andreas Schaerer; the accordion’s deep portentous chords sound like an organ behind the wandering piano arpeggios. The surface is glassy and the slow chords almost rocky. The pensive melody resonates, like the theme tune to a movie in your mind. Wollny grew up loving Schubert and Romantic music, and Peirani learned classical music by transcribing it for accordion; both have a wide repertoire of ideas to draw on in their version of Barber’s Adagio for Strings. It’s culled to a couple of harmonised lines, sonorous and tautly emotive. It moves into a Steve Reich-like section with fast, intricate chords that repeat ecstatically before falling back to the main theme. Time expands and contracts, but it’s all over in a few minutes. Hunter turns Björk’s electro-pop into dark thrummed strings, as high piano notes drip onto the strong accordion groove: part flamenco, part Ravel’s Bolero. Wollny’s solo has rhythmic hints of Corea, with abstract shapes and huge crashing chords. He scratches and dampens the piano strings in almost menacing flourishes.

Wollny and Peirani’s original tunes are at the core of the CD; you can hear their strong musical personalities pulling together and against each other. Wollny’s Bells has long atonal lines that chase each other like snowflakes in a blizzard- the album was recorded in the snow in Bavaria’s Schloss Elmau. It recalls the frenzy of one of his Hexentanz (‘witch dance’) pieces. It slips into swing, piano and accordion throwing boppy phrases to each other. In total contrast, Peirani’s mysteriously-named Did You Say Rotenberg? wrings strong feeling from a folk-edged three note minor motif, as the harmonies unwrap. Peirani toured with an Eastern European band, and there’s something of the Balkans in his colourful solo. Wollny adds jazzier harmonies, recalling Joachim Kühn in his angular solo. The two move in and out of phase with each other then come together like waves. Wollny’s Sirènes lures the listener in with a melodic riffs, dropping piano notes in unexpected places: they create lopsided timings and harmonies, changing colours over a still scene. Each instrument has a solo section, thoughtful and deeply Romantic. In Peirani’s Uniskate, Wollny strums the piano strings like a harp or dulcimer behind the bright accordion melody, played with a sense of nostalgic yearning. The piano bass lines seem to hold back the time then push it forward. For a few bars, Peirani’s chords (almost swing) pull hard against Wollny’s flowing arpeggios, as if they might break loose from each other. The rhythmic tension is astounding, heightening the emotion of the piece.

Gary Peacock’s Vignette has an intense treatment, a dark tango intensified by Peirani’s growling trills on the accordion: his blurred, fluttering sounds add a sense of mystery to the melody. Wollny’s solo is warm and expressive, echoing Peirani’s trills. When the piano melody returns, with high wistful accordion (accordina?) counter melodies, it’s especially beautiful. (As well as button accordion, Peirani plays accordina on the album- a kind of metal melodica- though it’s not easy to hear when.) Sufjan Stevens’ Fourth of July is slowed down, with rich textures filling the simple, tolling chords. This was recorded live at a concert following rehearsals at Schloss Elmau, as was Travesuras (written by Tomás Gubitsch, and Argentinian-born friend of Peirani.) Travesuras has an Hermeto Pascoal-like wild irreverence in its tango-influenced grooves; a slow central section heightens the fierce playfulness of Peirani’s solo working together with Wollny’s powerful grooves. Tucked away at the end of the track is a hidden song, unnamed. It’s Judee Sill’s The Kiss, with its classical cadences and plaintive melody: as gentle as a Brahms lullaby with harmonic twists to draw you in.

This is the kind of album it’s hard to write about: the two are such instinctive and accomplished musicians, that you want to simply absorb yourself in the music, and share their ideas and moods. ‘My speciality is that I’m not a specialist,’ Peirani has said. ‘I’m always curious about music and I try to play music in my way. I don’t care about the style. There is no borderline.’

Alison Bentley in londonjazznews.com

1 note

·

View note