#300 tang poems

Text

Translation Note. Songbie, 送别, “Farewell.”

Sometimes translated as “Parting Song.”

Wang Wei does not identify Nanshan, literally, southern mountains. Likely they are nearby Zhongnan Mountains, sometimes called the Taiyi Mountains, just to the south of the war torn capital of Chang’an.

Wang Wei, Tang poet, 8th c.

Dismount while I offer you some wine,

I ask, where and why?

You say, “Here things have not gone well.

I prefer to rest at the foot of Nanshan

. Give me leave, ask no more for.

White clouds are endless there.”

Wang Wei

Wang Wei was a devout Buddhist and councilor to Emperor Xuanzong.

Wang Wei, like many Tang officials, was caught up in the An Lushan Rebellion (755 to 763). Like the poet Du Fu, he was captured by the rebel forces. Apparently, he escaped, and, like Du Fu, was then accused of treason and pardoned. He was then reappointed to a ministerial post.

Whether this poem is about that turbulent period is unknown, nor is the reason for his death in 761 at the age of 60 or so.

Pinyin

Translation Note. junjiu. Line one, a play on words with wen jun, line two. Junjiu, a reference to Wenjun, a traditional wine produced in Sichuan Province. Sichuan is mountainous and south of Chang’an. It is also where the Emperor Xuanzong and his court fled to after the rebel sack of Chang’an. Nanshan is a common place name. Thus, it may refer to Nanshan, a small village in Sichuan, or the mountains of Sichuan.

Wang Wei, Songbie

Xia ma yin junjiu

Wen jun he suo zhi?

Jun yan bu de yi

Gui wo nanshan chui

Dan qu mo fu wen

Baiyun wu jin shi.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working on all these various translations has got to be the most educational fandom related thing that I’ve ever done. Now that I’ve pieced together a list of poetries that I’ve fully translated, and I’ve also translated an additional 18 more poems that aren’t posted yet, it’s quite interesting to see how different writers use these poems.

MXTX, for example, uses a lot of mainstream poems. She likes stuff from the Tang 300, with the occasional Song poem (example) on the side. For example, Wei Wuxian’s spell, Lan Zhan’s first appearance, Jiang Fengmian’s name, Yunmeng Jiang and Gusu Lan’s namesake poems are all derive from the Tang 300. She did use the Liang Dynasty’s Beauty of Nanyuan 南苑逢美人 in Wei Wuxian’s spell, but that’s a really popular poem that’s used everywhere. MXTX also uses Yuan Zhen’s Mourning in TGCF, and that’s a poem that kids learn in high school. I’m guessing that this probably because she was pretty young when she wrote MDZS and, it’s stuff that she learned in school.

SHL uses poems in a different way. Wen Kexing uses everything from the Qing Dynasty (1912AD) to the Zhou Dynasty (256 BC), but he uses predominantly Shijing (Zhou Dynasty - Waring States 221 BC) poetry to express his sorrow when he realises Zhou Zishu was dying. (SHL list of poetries) Shijing were basically folk poems during that time period, so essentially, he was sprouting poetry like a gentleman to flirt with Zhou Zishu, but spoke like a layman when he was mourning.

MXS (Thousand Autumns) also has a different choice of poetry. She uses stuff from 李商隐 Li Shangyin twice in Chapter 1 (Regret Peak’s one of them. I’ll post the second one on the 25/2), and his poems are notoriously difficult to understand. There’s also reference to a picture, and she also uses really obscure poetries that aren’t mainstream.

Here is the list of poems! Enjoy!

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

JTTW Chapter 40 Thoughts

Chapter 40 for the @journeythroughjourneytothewest Reading Group!

Deer, yey!

No antelope though, no no no.

Though as Anthony C. Yu mentioned in the notes this is a similar poem to one in chapter 20, so I already mentioned this.

Red Boy narrating to himself feels like such a child thing to do, I like it. Generally there seems to be a difference to his manner of speaking to most of the adults, which is very nice to see.

Love Sun Wukong calling out Zhu Bajie on his implicit bias against monster spirits given he actually knows some of them.

Also Tang Sanzang starting to learn to trust Sun Wukong’s expertise, it’s about time he does.

Maybe he shouldn’t point with his whip though, that’s just a little intimidating.

That Red Boy gives himself as a seven year old here carries numerical meaning as the German translation has stated in its notes! The number seven is associated with fire as well as the colour red.

Honestly Sun Wukong has every right to be upset in this situation.

Also really cute this brotherly moment between him and Sha Wujing!

So this is an awl.

I had no idea what that was, so here I present it to everyone for clarification. The German translation made a lot more sense to me, translating to drill head instead.

There exists also an Awl Pike as a weapon.

But given that it was developed in Germany and Austria and mostly relegated to there for usage as well I doubt that is what was meant here.

With this mountain the math doesn’t math. 30 each would only add up to 300 miles. I believe it’s a translation mishap and makes a lot more sense with the original measurement units.

Another deer mention. We have very generalized Mountain Deer or potentially Chinese Water Deer specified to be of the mountain, and Wild Deer.

I wonder if by childhood name they mean actual name or his milkname. A quick check of the Original Chinese version and indeed it is his milkname. Anyone spending even just a little time looking at Chinese culture probably already has a hunch as to what this is, but I’ll give a quick summary here anyways.

A milkname is essentially just a nickname for a baby for a couple of months after its birth before an actual name is decided upon. It is usually an insulting or at least plain name as well to keep evil spirits from taking an interest in the newborn. Very similar to traditional European cultures actually! In either place these kinds of nicknames aren’t really used anymore due to bureaucracy requiring a baby to be properly named at birth for record keeping.

#xiyouji#journey to the west#jttw#sun wukong#monkey king#tang sanzang#red boy#hong hai'er#jttw reading group#jttw book club

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The poem they are trying to reference with 7seas character summaries is part of Cloud Recesses namesake that is true, and was by Jia Dao, The Absent Hermit.

1 松下問童子

2 言師採藥去

3 只在此山中

4 雲深不知處

1 Beneath the bow of pines, I asked a disciple

2 My Master has gone to gather herbs that grow wild

3 Somewhere on these mountains

4 Hidden in the clouds unknown

The only thing ever directly in reference to this poem is the name of Cloud Recesses which is the last stanza of the poem "yún shēn bù zhī chù". Now it WAS compiled in an anthology called 300 Tang Poems by Sun Zhu foooooor... students as a study aid. And has been translated several times over the years. It is still used for literary today and is very common source of classic chinese poetry that chinese students at least, would be used to seeing referenced throughout media, books and curriculum.

Mo Dao Zu Shi itself is very much covered in references of Confucian standards as well as Daoisist belief. Conveniently for the story it uses plenty of poetic verses and idioms that were popular during the Tang Dynasty given it was considered the golden age of literature and arts for China. The orthodoxy of this for the setting makes it easy references to pick up on.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

卜算子·我住长江头 - Song of Divination · I live at the Long River’s head

by 李之仪 (Li Zhiyi, 1048 to 1117)

我住长江头 君住长江尾

wǒ zhù chángjiāng tóu, jūn zhù chángjiāng wěi

I live at the Long River’s head, you live at the Long River’s tail end.

日日思君不见君 共饮长江水

rì rì sī jūn bùjiàn jūn, gòng yǐn chángjiāng shuǐ

Day after day, missing you but not seeing you, together, in the Long River’s water we partake.

此水几时休 此恨何时已

cǐ shuǐ jǐ shí xiū, cǐ hèn hé shí yǐ

The time when the water’s flow ceases is when resentment for this passes.

只愿君心似我心 定不负相思意

Zhǐ yuàn jūn xīn sì wǒ xīn, dìng bù fù xiāng sī yì

May your heart be as mine. The love from which this longing springs shall not be in vain.

………………………………………………………………………………………….

Notes

TITLE

The tune pattern for this song is卜算子, commonly translated as Song of Divination. The character卜 (bǔ) is a pictogram often explained as a representation of the cracks that appear on scorched tortoise shells, one of the methods of ancient Chinese divination. And to 算 (suàn), to calculate, is of course another method of divination. There are some different opinions of what this tune pattern is named for. Some say that 子 does not refer to a person, and instead is short for 曲子 - a little song, some say it’s named for ‘a person who does divinations’. Undeniably, there is divination in the name, and a ci is a song. So that’s what I went with!

There are several famous songs with this tune pattern, by Su Shi / Su Dongpo and by Lu You (we should know him quite well by now), of which I would say Li Zhiyi’s might be the most simple yet deeply romantic. This is probably why it’s super famous… that and the fact that it’s in the 300 Song Lyric collection.

// random thought re: 300 Tang Poems, 300 Song Lyrics, 300 Yuan Songs, maybe they were all collected into these anthologies of 300+ works because the Classic of Poetry was originally called 300 Poems?

I love Su Shi’s song for it’s stubborn loneliness in the cold and also its calm. But Lu You’s is just !!!!!!!!!! makes me want to curl around it like a loving cat. Thinking about them both makes me want to share them too!!!

Some other day perhaps.

These are so famous I had no idea they were all using the same tune pattern - and I can’t explain how this one works because Song lyric tune patterns are still a mystery to me. Will share if I ever figure it out, but yeah… I’m nowhere near that point now ahahah.

BACKGROUND

Li Zhiyi, courtesy name - Duanshu, was a poet of the Northern Song Dynasty and an important member of the Su Dongpo circle.

(My man Su Shi was very popular and very beloved in his time with many students and even more admirers, we have talked about how he made friends wherever he gets exiled, how he has a good sense of humor and makes fun of himself too).

Born in 1048 and later becoming a student of Fan Chunren, son of Fan Zhongyan (also a very cool dude! He writes amazing things /cough不以物喜不以己悲cough/, so let’s talk about him someday ~) and passed the imperial exams to become a jinshi in the year 1070 at the age of 22.

Sixteen years later in 1086, Fan Chunren effectively became the prime minister while Li Zhiyi became a scribe at a military division for the central government, and then magistrate for Yuan Prefacture not long after. It was after this time that he began interacting frequently with Su Shi, Huang Tingjian and others from that clique. Li Zhiyi also worked for Su Shi in his Governer’s Office while he was the Governor for Ding Prefecture.

(From Su Shi’s Baidu entry: In 1093, Empress Dowager Gao passed away, so Emperor Zhezong was in power and the new faction rose in prominence again. Su Shi was eventually relegated far from the capital to Hui Province in 1094, and then Hainan Island in 1097.)

And so, in 1099, when Li Zhiyi was promoted to supervisor for the vault for incense herbs - a subdivision under the Minister of Revenue, he was censured for once working for Su Shi and suspended from his position. Unfortunately for him, at some point afterwards, he was recommended for the position of Envoy for Hedong (here’s an interesting article in Chinese on the position of Envoy), but struck from the list when he offended the new prime minister in 1101 with an epitaph for Fan Zhongyan, the use of which was disallowed, and was exiled for a time. At least that’s what I’m interpreting from 东都事略, Summary of Events in the Eastern Capital, a book chronicling Northern Song dynasty (960–1126) history, written by Wang Cheng, a Southern Song official in the historiographic compilation bureau.

He was then posted with his family to Taiping Province, where he stayed for four years. In his own words as referenced from 姑溪居士文集, Collected Works of Guxi Hermit, Volume 1 Chapter 21: In the first year, his son and daughter in law left this world, in the second, he fell ill, Spring and Summer passed like trudging through water and he was doing very poorly, in the third year, his wife died too. In the beginning of the fourth year, he suffered from a skin disease and other conditions.

From 挥麈录 Records of a Horsetail Wisk by Wang Mingqing, a court official of the Southern Song Dynasty, Chapter 6, it seems Li Zhiyi was eventually reinstated as a court official after he was granted amnesty. Cross referencing with events in Emperor Huizhong of Song's rule (he was half-brother of Emperor Zhezong and succeeded the throne after his brother’s death in 1100), it seems that in 1107, there was to be a change of Era Name in the next year and the Emperor had offered sacrifices to the Jade Emperor, Haotian Shangdi (the highest deity in Daoism and Chinese religion from Tang Dynasty onwards); a general amnesty was granted to all as well. But Li Zhiyi did not return to his post, and instead remained in Taiping Prefecture. And this is where someone new and important enters the picture.

Backtracking five years to 1102, Yang Shu (杨姝) was a courtesan of Taiping Prefecture at this time. We know more about her because Huang Tingjian, courtesy name Luzhi, the well known calligrapher, artist, scholar, government official, and poet of Song Dynasty (mentioned earlier as being close to Su Shi, just in case you forgot), wrote her several poems while he was Prefect there for nine days in 1102.

Who else was in Taiping Prefecture in 1102? That’s right! Our friend Li Zhiyi.

They played a little poetry writing game, the results of which were recorded in his Collected Works of Guxi Hermit, Chapter 47 as well: 好事近 · 与黄鲁直于当涂花园石洞听杨妹弹履霜操鲁直有词因次韵, (To the tune of) Good Tidings Approach · With Luzhi at Dangtu Garden’s Stone Cave Listening to Yang Shu Pluck Treading in the Frost, Luzhi has lyrics for doing a ciyun. This ciyun just involves writing lyrics according to the rhyme pattern of the original lyric; usually one person writes the first and then another composes a reply in the same pattern. In this case, Huang Tingjian went first, and Li Zhiyi followed. (Let me know if you’d like to see what they wrote!)

During that same period, or perhaps thinking of this day some time after, Li Zhiyi wrote her two more poems to the tune of popular songs. Huang Tingjian wrote one for her as well, calling her a ‘little singer’ in the short prelude to his lyric 好事近, 太平州小妓杨姝弹琴送酒, (To the tune of) Good Tidings Approach, Taiping Prefecture’s Little Singer Yang Shu Plays the Qin and Brings Wine.

And again, from Records of a Horsetail Wisk, we learn that Li Zhiyi, childless and widowed, remarried Yang Shu and brought her home. He was in his late fifties, probably nearing his sixties by this point, and she was his junior by many decades. Miraculously, they had a child together. But it was also this union that was the soft target for trouble to be brought upon them some ten years later - Guo Xiangzheng (郭祥正) who was an enemy of Li Zhiyi had someone accuse their family of falsifying the parentage of this child, such that he could be conferred privileges. (And I assume this is because Li Zhiyi is technically still a court official? If it was something else, I’m unable to track it down…) For the second or third time - I’ve lost count - Li Zhiyi’s name was struck from the court’s records and Yang Shu was sentenced to caning.

We have a poem from the delighted Guo Xiangzheng to learn of the aftermath:

七十馀岁老朝郎 | Seventy and more, the old court official,

曾向元祐说文章 | in Yuanyou era, essays he did compose.

如今白首归田后 | Now white-haired and retired,

却与杨姝洗杖疮 | instead, he washes Yang Shu’s cane welts.

…bro… :/

Yes, we know they were wronged because Li Zhiyi’s nephew and student eventually helped overturn the case and reveal the truth. The text says ‘wife and child were returned to him’, so I imagine they were either jailed for the ‘fraud’ or returned to Yang Shu’s original class and separated from Li Zhiyi. Again, his official status was restored to him and in addition, the post of Grand Master for Court Discussion, but he declined this in favour of his retirement life.

After so much reading, I am still not able to pinpoint a year in which卜算子·我住长江头 was written. Only a general time period of ‘much later in life’ and possibly after having met Yang Shu simply from its place in his Collected Works of Guxi Hermit, Chapter 45. What seems to be certain though, is that it is written for her, and I am glad to hear however indirectly that these feelings were sincere.

Only in the fiercest fire, do you know what’s real gold and all that…

POEM

I would never have guessed that these words were from an old man, because they’re so bright, the emotions so fiery and all the more so for their simplicity.

There is drama in that hyperbole of distance. The Long River is 6300 km long. But how unreachable and impossible is the distance between them, is also how they are connected. Like how we might look up at the sky when a loved one is far away and take comfort in the fact that that they are under the same sky, or looking up at the same moon. Feelings are ‘entrusted’ to a moon, the stars, a river.

I feel like making or forcing this connection figuratively or via physical action of drinking the water from the same river, is absurdly childish yet charming. ‘思君不见君’ Thinking of you but not seeing you is a common lament, and then… here’s something that’s (not) going to make you feel better!

How Not Better are we?

Well... how likely is the Long River to cease its flow?

The resentment springs infinitely like water from the river’s source, what is the source of the resentment though - that’s love. Hence, this love will stop when the roaring river stops: never.

And the thing to remember, at least from how I read this poem, is that it’s one sided. ‘只愿君心似我心’ I only wish that your heart is as mine. He doesn’t know, but he knows. The second part of this line is not a condition but a promise, a statement of fact emphasized beautifully in that 定 ‘for sure’.

Source

#李之仪#卜算子#卜算子·我住长江头#poems#northern song dynasty#you DO not want to know how long i was stuck reading for this#and how much i ommitted#LMAO#so so so many kudos to the meticulous souls who put together timelines of these people's lives on wiki#baidu and all#i really appreciate it#AND CTEXT PROJECT#AND WIKI TOO#oh my god it's so amazing#lifesaving#and to mr c for 断句ing for me when i couldn't read anymore lmao#commentary

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resource List

List of freely-available online sources only, some of which are translated into English. Will be updated sporadically.

Last update: Nov 26, 2022.

GENERAL (English)

A Chinese Bestiary by Richard E. Strassberg

A nice if incomplete translation of the Classics of Mountains and Seas (Shanhaijing) that focuses on the creatures. It goes into considerable detail and background, unlike Anne Birell’s direct translation. It does not, however, translate the numerous sections listing mountains with no creatures.

The Nine Songs translation by Arthur Waley (Available on the Internet Archive)

A translation of the Nine Songs from the Songs of Chu.

Six Chinese Classics translation by A. Charles Muller

Consists of Analects of Confucius, Great Learning, Doctrine of the Mean, Mencius, Daode jing and Zhuangzi (Chapters One and Two)

Book of Poetry translation by James Legge

300 Tang Poems (Available online) (Alternate link)

“Sui-Tang Chang'an” by Xiong Cunrui

An unbelievable resource for anyone seeking information on the Chang’an city during the Sui and Tang dynasties. It has maps and fully listed names of all the wards and Imperial City interior buildings, and even a compiled list of known inhabitants of the city as well as which wards they were reportedly living in.

Brill Chinese Reference Library: Title of Officials translation by Michael Loewe

Translation of titles from the Hanshu, I believe.

The T'ang Code, Volume I: General Principles translated by Wallace Johnson

The T’ang Code, volume 2, Specific Articles translated by Wallace Johnson

Tang dynasty law code. Can probably also double as “tag yourself” meme if you want.

“Epidemic and population patterns in the Chinese Empire (243 B.C.E. to 1911 C.E.)” by A. Morabia

The Ideology of the Guqin

USEFUL SITES

cbaigui.com

A wonderful site compiling bestiary entries from many ancient Chinese texts, including but not limited to Diagrams of Bai Ze, Old Book of Tang, Book of Rites, etc. You can search them sorted by book or by dynasties, which is a feature I never knew I needed until I saw it.

ctext.org

We know it, we love it, the MVP that compiles so many of ancient texts, and some of them have translations (by James Legge) too.

In Conversation with China Youtube Channel

Collection of online talks/lectures on various topics, including Classic Chinese grammar, Dunhuang Cave Manuscripts, etc. Personal biases, but some of my favorites are the ones by Sarah Allan, Donald Harper, and the series that explores the definition, perception, and treatment towards those with disabilities in early China.

Wikisource 古文 Category

I really just stumbled upon this looking for 白泽精怪图 but it has a number of misc texts in Traditional Chinese.

chinaknowledge.de

Another classic. It’s an incredible site for anyone looking to jump into a specific topic; you can pick up from there.

100jia.net

It’s kind of a headache to navigate it at the start but the link provided should send you to a page with a long list of ancient Chinese classic texts as well as several existing online translations of them. It’s in German, yes, don’t mind it.

Resources on Chinese Legal Tradition

TANG DYNASTY SPECIFIC

"The Reconstruction of Yongning Ward" by Heng Chye Kiang and Chen Shuanglin

Details a theoretical and digital reconstruction of a particular ward of Chang’an during Tang dynasty, including population estimate.

The administrative divisions of the Tang dynasty

唐朝官员品级 Tang dynasty official positions ordered by rank

中国俸禄制度史 The history of China's salary system

CREATURES, FOLK RELIGION, ETC

"The Textual Form of Knowledge: Occult Miscellanies in Ancient and Medieval Chinese Manuscripts, 4th Century BCE to 10th Century CE" by Donald Harper

I’m not even gonna try to describe it right now you can figure it out by reading the title

Ho Peng Yoke books on Archive.org

Includes "Chinese Mathematical Astrology: Reaching out for the stars" and "Explorations in Daoism Medicine and Alchemy in Literature".

龙是如何进化的:龙纹史考 by 陈涤

A post that chronicles the development and changes to the form of the dragon across dynasties.

龙头鹿身的就是麒麟?都弄错了!麒麟的秘密大公开! by 天可汗文化

A post that chronicles the development and changes to the form of the qilin across dynasties.

“Bai Ze special” by 哀吾生之須臾

白泽特辑【一】「白泽」的传说

白泽特辑【二】「白泽」的形貌

白泽特辑【三】「白泽图」的相关概况

Bai Ze, Ephemera and Popular Culture by Donald Harper (paper available on the Methods on Sinology site, but site is under construction)

白泽志怪 by 白泽君

One man’s attempt to piece together Diagrams of Bai Ze and explore Bai Ze as a myth. This particular post attempts to put together the surviving entries of the lost text.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qin Shi: Isn't he reading poetry today?

Cai Liang: He already did. If he were born in ancient times, there would've been more than 300 Poems of the Tang Dynasty.

This made me LOL so hard! Cai Liang is honestly a hoot. And such a great friend, too!

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh lol found my lost bus pass

it was acting as a bookmark in my grandma's Tang 300 Poems

well whatever. my WIP li shangyin translations have to wait; i'm being crushed under school project deadlines rn

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

杜甫草堂(Du fu thatched)

The former residence of the great Chinese poet Du Fu when he lived in Chengdu, is located at 38 Qing Hua Road, Qingyang District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Du Fu lived here for nearly four years and composed more than 240 poems. At the end of the Tang Dynasty, the poet Wei Zhuang found the site of the Cao Tang Hall and reconstructed the hut so that it could be preserved, and it has been repaired and expanded throughout the Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Du Fu thatched covers an area of nearly 300 mu and still retains intact the architectural pattern of the Ming Hongzhi 13 (1500) and Qing Jiaqing 16 (1811) years of repair and expansion, with the Shining Wall, the main gate, the Great Hall, the Hall of Poetry and History, the Chai Gate, and the Gongbu Ancestral Hall arranged on a central axis, flanked by symmetrical cloisters and

other ancillary buildings. There are more than 30,000 volumes of various materials in the Cao

Tang, and the Du Fu Memorial Hall was established in 1955 and renamed the Chengdu Du Fu Thatched in 1985. On March 4, 1961, it was announced by the State Council of the People's

Republic of China as the first batch of national key cultural relics protection units.

https://huaban.com/pins/4140122773?modalImg=https%3A%2F%2Fgd-hbimg.huaban.com%2F29b8d41a19741cea4d623e7d91986659b7a020f66be7a-E4WtFF_fw1200

https://huaban.com/pins/4343396431?modalImg=https%3A%2F%2Fgd-hbimg.huaban.com%2F4804b40c60542e484c7f220910b5b88606ffe28767b0c-TXHrL4_fw1200

https://huaban.com/pins/4659696516?modalImg=https%3A%2F%2Fgd-hbimg.huaban.com%2F00906499d0658edff28b1efb4feb24c632fd263055310-ib6Itz

https://huaban.com/pins/4140122210

0 notes

Text

Moon Goddess’ by Li Shangyin

The candlelight is flickering on my stone screen,

The Milky Way is fading, the Morning Star is falling from the sky.

Moon Goddess, are you not sorry you stole our immortal potion,

Over the blue sea and sky – seeing my lonely heart every night.

Translation Note. For Chánghé, 长河, I used the familiar term Milky Way whereas the Chinese would use Heavenly River. The similar sounding Cháng É, 嫦 娥, the Moon Goddess, is delightful.

Ye Ye Xin is hard to translate. For ye ye, 夜 夜, I come up with “every night” and “heart” for xin, 心. Then I imagine the lonely archer looking up at the sky and the moon, wishing he had been a better ruler and husband.

Well, that’s life and it is too late to deny it.

Fly Me to the Moon

Short poems like Li Shangyin’s Moon Goddess were often put to music. Can you hear the melody of the words –píngfēng, xiăoxīng, língyào, qīngtiān, that’s poetry. There is no denying it.

Similar expressions of the moon and love can be found in 20th century American music.

Moon River, a song composed by Henry Mancini, lyrics by Johnny Mercer, is a well known example. Mercer’s lyrics, “moon river, you heart breaker” captures the feeling of Li’s last line — bìhăi qīngtiān, yè yè xīn, “Blue sea, blue sky, every night can you see my heart.” Okay, some words are implied, but that is true of every poem and song. Fly Me To The Moon, “and let me float among the stars,” a dreamy song by Bart Howard, made famous by Frank Sinatra, also comes to mind. Listen to Billie Holiday’s Blue Moon for a more melancholy mood.

As for poetry, join Li Bai and the moon on any starry night, a connection so strong that it is said he tried to grasp the moon’s reflection from a boat on a lake and drowned.

Chang E and Houyi

Houyi, Lord Archer (to Chang E, his lovely wife): Chang E, on such a morning when the sea and sky are pale blue, when the Heavenly River fades into the distant ocean, and the Morning Star flickers on the water and falls away, Chang E, are you not saddened by the long, lonely nights?

There are several stories about Chang E, the moon goddess. One version tells this tale. Chang’e was a beautiful woman, wife of Houyi, an accomplished archer.

Once upon a time, ten suns rose in the sky, one following another, all day. The land was scorched the crops burned, the people suffered. Lord Archer, Houyi, shot down nine suns, leaving just one. And a grateful Queen Mother of the West gave him an immortal elixir as a reward, enough to share with his wife, Chang E.

Proclaimed king by people in the Middle Kingdom, Houyi became a tyrant. Chang E, fearing that he would rule forever, drank the potion and fled to the moon to escape her hot-tempered husband.

Li Shangyin was a poet of the late Tang dynasty. The forty-five years of his life (c. 813–858) encompassed the turbulent reign of six emperors and the rising influence of the palace eunuchs. The tale of one emperor, Wuzong, recalls the story of Houzi and Chang E and their immortal potion. Wuzong began taking pills hoping to lead to immortality. His mood became angry and he died six years into his reign.

The circumstances of Li Shangyin’s own death are not recorded. He was however considered the last great Tang poet.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

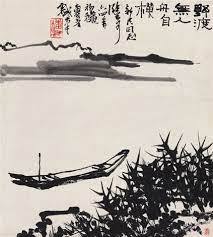

There was no one at the ferry in the wilderness; save for a small boat that lies on the water leisurely. "野渡无人舟自横" - The meaning of Fei Du 费渡 and Luo Wenzhou 骆闻舟's Name. (Wei Yingwu 韦应物- Chuzhou’s Xijian 滁州西涧)

I’ve never analysed a priest related meta so here’s a first for me I guess.

It’s a known fact that Fei Du and Luo Wenzhou’s names were censored when the Modu adaptation was released. The names just stuck out to me so I did some research and WOW, their names were from the same line in a poem (OBVIOUSLY).

And it's a very famous poem too, which is probably why their names were changed because everyone knows what Priest was trying to imply.

So anyway here it goes ~

Their names arise from from Chuzhou’s Xijian 滁州西涧 written by the Tang Dynasty Poet Wei Yingwu 韦应物 (lmao this dude's courtesy name was Yibo XD) . Chuzhou’s a city located in the Anhui Province. 西涧 Xijian refers to a river located west of Chunzhou. When the poet was the governor of Chunzhou, he frequently visited Xijian and thus, it inspired him to write this poem. Wei Yingwu has a reputation for writing poetry based on scenery so here's one of them!

独怜幽草涧边生,上有黄鹂深树鸣。

The only thing I like is the lonely grass that grows by the stream that runs through the valley, and the orioles that cry out in the deep undergrowth.

T/N: 独怜 is a very interesting word. 😍. It can be broken down to 独 (unique, alone) and 怜 (pity, love). So in this case, most people would interpret this as something was so unique and the poet loved it, or it could also mean something that was lonely and pitiful 🥲

春潮带雨晚来急,野渡(DU)无人舟(ZHOU)自横。

In the evening, when the spring tide rises and the rain drizzles, the water in the Xijian river becomes increasingly turbulent. There was no one at the ferry in the wilderness; save for a small boat that lies on the water leisurely.

"野渡无人舟自横" is a very famous line (Tang 300!) and it has inspired many to draw based on this line alone.

Drawn by Zhang Pin in 1963.

And another painting by Pan Tianshou in 1964

To fully understand this poem, we have to start from the poet’s background. Wei Yingwu came from a rich family, and when he was 15 years old, he was the aide of Emperor Xuanzhong. In the early days, he was unruly and the villagers under him suffered. During the An Lushan Rebellion, Xuanzhong fled and Wei Yingwu lost his job. Wei Yingwu then put his mind to studying and eventually, he became an official. It was said that his past turbulent experiences in his life (the An Lushan Rebellion in particular) inspired his poem.

As a bonus point, you’re absolutely right if you’ve read modu and found the vibe of this poem to be very familiar. Because Priest has used similar imagery throughout the novel. For example, in Chapter 95:

He was like a traveler walking through the desert, his body utterly broken. And Luo Wenzhou and this tiny house was like a bottle half filled with water that fell from the sky. Even if it contained arsenic, or if the cold broke apart his fingers one by one ... he could not give it up. - Translation by yours truly.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

I love footnotes that give you background. Dude straight up killed a guy for retiring then felt bad about it and made sure everyone knew it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

son-in-law is the cutest

From episode 29:

金风玉露一相逢,天上人间不算数。

在天愿为比翼鸟,在地愿为连理树。

Novel!canon Cao Weining is the king of messing up poetry & drama!CWN is no different. CWN's nickname is son-in-law, so I'll just be calling him SIL since that's what I'm used to; A-Xiang's nickname is "daughter". 😛

There aren’t really any hidden meanings here, just SIL professing his love for A-Xiang and foreshadows their BE 😢

The first two lines come from the poem 《鹊桥仙》.

The first line: 金风玉露一相逢

Literal translation: A chance meeting when the golden winds* blow, and the ground covered with dew the colour of jade**

SIL: 天上人间不算数。(tian shang ren jian bu suan shu)

Meaning: Nothing counts, whether it's in the heavens above or in this mortal world.

Original poem: 便胜却、人间无数。(bian sheng que, ren jian wu shu)

Meaning: But it's better than the innumerable other meetings in this world.

This poem refers to the cowherd & the weaver girl's love story, where they were not allowed to be together. One day a year, on the 7th day of the 7th month (qi xi), a flock of magpies would form a bridge across the heavenly river so they can reunite.

The whole meaning of this line is: When the golden autumn winds blow, and white dew rests on the ground, to meet (with you) just once is more than the innumerable other meetings in life.

I'm *guessing* what SIL means is: When the golden autumn winds blow, and white dew rests on the ground, to meet (with you) just once would make the rest of the world meaningless.

The next two lines come from poem 《长恨歌》:

SIL: 在天愿为比翼鸟,在地愿为连理树。(zai tian yuan wei bi niao, zai di yuan wei lian li shu [tree])

Original poem: 在天愿作比翼鸟,在地愿为连理枝。(zai tian yuan zuo bi yi niao, zai di yuan wei lian li zhi [branch])

Meaning: In the skies, I'm willing to be two inseparable birds*** flying together. On the earth, I'm willing to be two branches**** interlocked with each other.

It's "interesting" that both the poems SIL/CWN quoted, well, misquoted here, are all tragic (compared to the occasionally happy endings of the love poems that Lao Wen quotes for A-Xu). The first poem talks about the cowherd and weaver girl, who can never be together except for a single day a year. The second poem is very well known, featuring Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang dynasty and his Beloved Consort Yang (Yang Guifei).

T/N behind the cut

Also i finally made a tags page, so people can find stuff. After all, 300/301 posts are about WoH. For posts similar to this, follow this tag.

*Golden winds refer to the autumn winds blowing golden leaves.

**Jade dew refers to White Dew (白露), a name of a season in the old calendar, around the 8th of September.

***The bird he mentions is "bi yi niao", it's a mythical pair of birds in Chinese folklore, where the two birds each have one eye and one wing. They can only fly when they're with each other. I can't find the English translated name for this, so I'm using pinyin. Although SIL used a slightly different word in the first line, the meaning is the same.

****The correct phrase should be "连理枝" (lian li zhi). It refers to branches from separate trees (different roots) that have grown and interlocked with each other that it's impossible to separate. It's also known as "husband and wife trees" or "life and death trees". There's nothing called a "连理树" (lian li shu); SIL just mixed up the name here, that's all.

LOOK AT SIL’S HAPPY PROUD FACE AT HIS OWN POETRY SKILLZ

#this was so hard#o.o#word of honor#xiangcao#cao weining#gu xiang#my lack of culture#xiao cao's happy proud face#he's adorbs#i added pinyin for the poetry#to make it easier to spot the differences

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

(literally just yearning. 300+ words of yearning)

bored?

lonely?

not being gay enough?

try falling in love with your best friend!

starting young is the ideal option, for it leaves your entire childhood peppered full with memories of their face.

throw yourself into a pit of adoration beyond despair, recognize the insanity and then ignore it, love the air they exhale

Love them to the point where you don't even think of a face anymore when recalling them, rather your mind fills with memories of laughter and warm hands

now the real fun part is to dwell in this glorious despair for a few years

then once you tell them, realize that both of you feel this strongly, yet can't act. bask in the sunlight of requited love before tumbling into a new world of casual romance

you will adore the way that your mind has a filing cabinet of moments, of words mumbled in the dark. "I think we are platonic soulmates" "yeah, I love you too" "common, grab my hand, I'll pull you up"

hopefully they will be lighthearted about the experience, teasing you softly - always softly - while they joke about how at least the two of you will be connected forever

young love is so impossible, a formula of explosions. but if you succeed, then you will live. you will feel every touch, every word, every glance.

"you are the only person I would die for" "I would never let you die"

relish the sweet sound of their poems, the snarky tang of their insults

and you will cry. oh goodness you will cry. you will cry from memories, you will cry over impossible futures. you will cry for the gifts you have

and you will remain friends. neither want more. neither want less. you will put your head in their lap and listen to them talk while they braid your hair, you will give them plants, hugs and cookies.

bored? lonely? not living?

try falling in love with your best friend

without thinking that they are in love with you

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Song of the Bronze Immortal Leaving the Han - Li He

Foreword: In the 8th month of the 1st year of the Qinglong Era (237 AD), Emperor Ming of Wei ordered his palace official to move an immortal of the Emperor Wu of Han (d. 87 BC) south by cart. This immortal, holding a dew-plate, had been installed in front of the palace hall.

The immortal started its journey once the palace official dismantled and removed the plate, whereupon it shed silent tears.

Upon which Li Changji, scion of the Tang royal house, composed "Song of the Bronze Immortal Leaving the Han." [1]

--

In fall the youth Liu came lightly by his flourishing mausoleum[2],

One heard his horse whinny in the night; he left no trace at dawn.

The rich scent of autumn is hemmed by osmanthus[3] and balustrades,

Thirty-six palaces, all, mossing over jade-green.[4]

The procession begins its thousand miles, led by the man of Wei,

Out the East Gate, a sour wind like arrows to the eye.

The Han moon was lured outside the royal walls in vain;

Our tears turn to drops of lead in imperial solemnity.

Fading orchids in mourning garb[5] line the Xianyang road,

If the heavens too could feel, the heavens would grow old.

Bearing our plate of dew alone through moonlit desolation,

River and city[6] far behind, the voice of waves grown small.

--

Li He, Tang superstar "demonic poet", wrote this poem en route from Chang'an to Luoyang -- the same route the statue was taking. (The statue, in actual history, never made it to Luoyang and got left in Ba City, due to the troublesome size or manifested tears, who knows.) The poet was leaving the capital bc he had to quit his post due to chronic illness. (You can see more of my research notes in my tumblr tag for this poem.)

1: I've inserted the corresponding Gregorian dates, but this is all Li He's own foreword contextualizing the poem.

There are 3 dynasties, 3 nested layers of history, at play here.

Emperor Wu ("martial") - birth name Liu Che - the Han dynasty flourished under his rule due to all the conquering and wealth; like many emperors before and after him, he became obsessed with attaining immortality. hence the poet calling his statue "bronze immortal". According to the commentary in my 1983 Chinese-lang Tang anthology by one 朱世英 Zhu Shiying, the statue this emperor commissioned of himself was enormous: 20m (丈) tall and 10m (围) in circumference. The "dew-plate" is a dish designed to collect morning dew as an offering to the heavens (in hopes of exchange for immortality?) - they're found on top of some Buddhist pagodas also.

Emperor Ming - birth name Cao Rui, grandson of the Cao Cao - 300 years later in the Wei dynasty, he ordered people to remove many Han artifacts from the imperial palace to Luoyang, an expensive and dangerous affair, replacing them with his own commissioned statues, etc etc. The "palace official" refers to a court eunuch - not sure if this is meant to be a specific person.

Li Changji, scion of the Tang royal house - the poet himself (Changji was his courtesy name). i wasn't able to find a genealogy but i do know his was a minor branch of the Tang dynasty founding line; he was quite poor and unsuccessful at getting a good court position (poets is the same). You can read more wild facts about his life on his wikipedia page.

The Tang poet is imagining the statue in the Wei remembering the living Han emperor. History repeats. Rulers grow dissolute and wasteful. Dynasties break, unite, then break again.

2: This first couplet seems unmoored from the rest of the poem. Is it a ghostly vision? a memory? The youth Liu, Liu-lang, is a ballsy way of referring to Emperor Wu. He's visiting his own royal tomb, Maoling Mausoleum (it's on wiki - highly rec the satellite photos, it's still standing), literally translated as "flourishing mausoleum". He started constructing it in his 2nd year of rule - he was 16 years old.

3: 桂树:Commonly mistranslated as "cassia" (chinese cinnamon) due to its prominence in traded goods, but in poetic context usually means 桂花 osmanthus - the smell is peaches, not cinnamon. The blooms are associated with the much-vaunted imperial examinations in eighth month (around September); sort of the equivalent to the greek laurel.

4: 三十六宫 土花臂:A difficult line to fit in english metre, because "thirty-six palaces" takes up the entire first half of the original line. And then the second half is an odd phrase probably coined by Li He - "earth flower jade-green".

5: I know my friend has explained this one already but I just need to yell again about how many images are packed into two characters, 衰兰 "withered orchids". (a) 衰 pronounced shuai, "frail," "old." The flowers are withering because it's autumn. (b) shuai, "reduced." There are few flowers left, and the flowers represent the crowd seeing the procession off. Barely anyone cares about the statue in this new dynasty. (c) pronounced cui, "mourning garments." Now this is a bit of a stretch, but I'm imagining the orchids as white with brown edges (the withering) - as in white and sackcloth mourning clothes. They're symbols of mortality they're the last few loyal mourners they're moved by emotion and thus are able to age, unlike the unfeeling heavens in the next line.

6: Originally says 渭城 "Wei City" in the poem, i.e. city on the Wei river, i.e. Chang'an. Both the Wei and Jing are famous rivers - Chang'an sits near where they touch. There's a nice parallelism b/t the sound of the waves growing small (or faint) and the heavens not growing old in this stanza that not many existing translations point out.

7 notes

·

View notes