#// but i'm also ready to pick it apart like a vulture

Photo

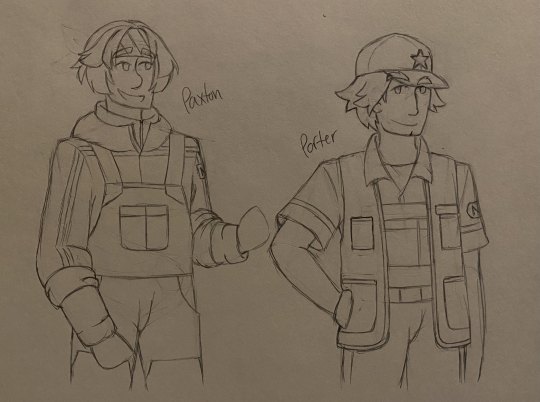

more engine designs! whistle wednesday has just finished season 20 and we all live in fear of bwba but we’re living the high life right now and I’m planning on riding the hype train all the way to our inevitable crash

#seki's art#thomas the tank engine#thomas and friends#ttte#ttte humanized#ttte rosie#ttte spencer#ttte diesel#ttte salty#ttte daisy#ttte bert#ttte arry#ttte molly#ttte stepney#ttte paxton#ttte porter#// i'm joking (mostly) about bwba#// but i'm also ready to pick it apart like a vulture#// but before that we have jbs and tgr and i'm so excited#// my art stamina has been slowing down but i'll try to keep some what consistent#// might draw some whistle wednesday jokes next lol#it takes a railway au

177 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could I request scenarios where Suga, Bokuto, Tanaka, and Kuroo's s/o pushes them out of the way of an oncoming car that runs the red light while they're crossing the road and she gets hit instead? You can have free reins with the endings/result; I'm just in the mood for some crying, scared angst. ^^; Thanks so much, love!

I opted to do shorter scenarios but for all of the characters you asked for, as an exception to my new announcement. Although I’m sad that I couldn’t write long bits for all of them, I thought this was brilliant for some practice on grief, and I’m sorry if they’re... if they make you sad. I hope you enjoy them all the same.

“They say that time heals all wounds,

but that presumes the source of the griefis finite.”

When they come to him, five hours later, the onlything they want are his words. Sugameets their eyes, unafraid, when he already had a foot dipped in fear, hisother drawing circles with its sticky grey residue.

Their lips move, eyes beady and unwelcoming. Shouldersheld rigid and feet a shoulder apart. Suga offers them nothing.

They begin with two officers, both women, one youngerthan the other, but both equally grim. They speak to him slowly, stretching outtheir words as if describing death to an infant, and Suga stares emptily atthem in return as they turn their head this way and that in slow arcs in amimic of the circle of life.

When there’s no sign of recognition, the older onefrowns, hand impatient on her hip and she turns to her partner, whispering soloudly that she needn’t have bothered unless her audience were all deaf. Barelya foot away, Suga picks up every word they say, listens to the emotionlesscontent and remembers none of the words.

The younger officer gives him a critical look, takesthe arm of her partner and vanishes past a corner. With nothing else to careabout, Suga’s gaze trails after them.

Two hours later, they reappear with her parents. Followingbehind the two officers, they’re crying, glistening smears all over theirblotchy faces. They fit right in with the other people loitering about in thetrauma ward.

Her mother is the first to touch him. She holds him bythe shoulders, her fingers digging into the dips of his tendons, surrenderingto the urge to shake the facts out of him like a piggy bank. She can’t find thewords to say either, and continues to sob silently while she shakes him, andSuga counts the number of times she shudders violently enough for the tears to spillfrom the creases along her eyes. Her father looms behind his wife, kind faceashen and uncaring when he asks Suga with a trembling voice if he could speakto the officers.

Suga shakes his head slowly. He can’t find a singlereason why he would open up to anyone. He can’t find a single thing worthsaying that wouldn’t put the truth to shame. A dozen witnesses’ words should beenough—an objective truth that they could put on paper and leave him be.

Her mother drags him into a hug. Her spindly arms aredeceptively strong, and those pinching fingers migrate around his shouldersuntil they’re crushing him bone by bone. She hangs onto him like one would abuoy; uninterested in comfort unless it’s a life raft, and Suga doesn’t move aninch. She’s trying to float on a sinking ship, but he says nothing; it isn’t asif in saving her, he could save himself.

Strategically positioned, the older policewoman peelsthe mother off of him with her nails and a flex of her arm. She frowns at Suga disapprovingly, but stepsback to let her younger partner hand him a notepad and pen. She suggests hemight prefer to write, if he can’t bring himself to speak. As if instead oftraumatized he’d just had his voice knocked out of him.

Suga takes both items into his hands and rubs a thumbover the dented ball-pen. All four bystanders around him watch on with suchintensity that Suga has to wonder if watching people scrawl down their feelingshas become a national sport when he wasn’t watching. They’re waiting for him todrag the ink over the faded lines just like spectators cheering for the lionsto be released into the arena.

She’d probably be unimpressed if he got himselfarrested out of spite. He counts the letters as he writes, a miserablebullet-point at the beginning of each sentence. He doesn’t go over five lines,and ten words for each one. His heart isn’t a collector’s item, and having moretestimonies isn’t going to win them any more compensation.

When the younger policewoman takes back the pad andpen, she inspects his descriptions with the same frown and mutters something toher colleague.

They all leave him at once, having extracted what theywanted. Suga hears from just at the edges of his range that they’ll be back ina few days, looking for a longer testimony. He disposes the fact from his mindfive minutes later.

- - -

At home the next day, his mother knocks on the doorand twice she calls his name as if it would break from sound alone. Althoughit’s someone familiar here for something more than facts and answers, Sugacan’t bring himself to care. His mother lets herself in anyway when there is noresponse.

Holding a page from the local newspaper limply in herhand, she lays the obituary on his lap. The relevant section is circled inpencil in a hurried job to ensure Suga knows exactly who it is he should bereading about, in case he might have forgotten. How very kind.

“They’ve invited you to speak at her funeral,” hismother says. “You’d go after her mother.”

She waits for an answer but Suga has none to offer; heimagines the crowd of people who had never really cared about her or her laughterbut seeming to flock to her funeral as if her ghost would pass judgement on them.His mother waits a few minutes but leaves him be after a long silence, pityfree on her face.

Alone, the walls seem to watch him all the moreintensely than if they had eyes. His furniture presses in, stealing more of thehollow room with each inward crawl.

Still, Suga sits. The compression cannot reach him.His own walls press back the way he has practiced, and in his mind, he fightseffortlessly for the meagre space to breathe in his own room.

By the time the crack of light through his curtains dim,Suga approaches his desk and takes a seat in his cushioned chair. There is adent where he sits on it each day, and his stationery is lined up neatly forhis right-handed convenience. He pulls out the nearest notebook from his stack,flips past the finished homework, and settles his pen on the first blank pageit reaches.

When the first sentence comes out rigid and ugly, Sugaalmost breaks the page crossing it out in rapid lines. He tries again, pickingout words in his head before they reach his hand, but none of them fit. ‘Condolences’and ‘memories’ are treated with the same harsh slashes.

By himself and with onlookers that have no hands, noeyes and no opinions, Suga brings himself to try a little harder, yet each wordthat he selects from the jumble of a thousand combinations sounds artificial,unforgiving and disingenuous. All the other combinations that aren’t so, digtheir hooks into the sides of his throat and there isn’t a single sound thatSuga attempts to make that doesn’t drown him as quickly as they rush up fromthe pits. His hand stops because the letters have become hideous, scrawlingthings, and because the next words at the ready are waiting for him to falter.

Suga turns to another page, flipping from the back ofthe book, and gives in to the sour feeling in his stomach that has no interestin his stoicism and dry eyes.

He writes his eulogy. He is conscious of everysentence, every sentiment—even his handwriting. The feelings don’t roar norspill out like they do for everyone else—he has to push them through, rollinghis tongue around the invisible words that he takes care to not say aloud incase they start to slither out and wrap around his throat until it’s swollen,blue and motionless on the evening floor.

Quietly, secretly, Suga also writes his love letter. Atiny, worthless love letter for a great, dead love; a great grief and a great,grey feeling that threatens to smother all the other greats into a perpetualfeebleness. He writes so that he isn’t smothered before he can remember whathis love was like in his chest, before his head breaks apart all the jaggedpieces from its walls and places into a safe box where Suga can’t ever cuthimself on. He writes to recall all the lighter moments, the heavier eveningsand the ridiculousness of moments that had never made any sense in the present.He lowers them all down with cautious fingers, smoothing their edges until theink stains his fingers.

He can feel it—this will be his last time speaking,writing, singing and thinking of her with his chest split in half and his bloodbeating in his ears. It doesn’t bring him any more joy than ordinary memoryusually does, but this is a love letter, and Suga’s letters are always intendedfor the person on the other end of his mailbox. It has never mattered to himhow he feels, and today the least of all.

He decides on the last sentence, and when it iscomplete, he folds it into meticulous quarters and slips it into his bag. Thisletter’s mailbox is a far one, past a fire and beyond a cliff for its charredlittle remains, beyond the reach of any person who wants his story, his lifeand his pain for their funeral where tens of people who haven’t even heard her laughwill congregate like vultures.

He’s ready. Suga takes a deep breath, closes his heart,and begins another speech.

This second piece he hands later to his motherdownstairs. She is astonished to see him, relieved and too worried to have satdown for longer than five minutes. “Why are you giving me this?” She asks, eyeswide and offering the bit of paper back to him. Suga faces her slowly and declineshis invitation to the funeral.

A week later, Suga leaves home for a short trip. Theschool lets him be, and his mother simply waves him goodbye with her liptrapped between her teeth. His father has her face tucked in the crook of hisneck, and stares helplessly at his son.

Up until the moment Suga’s feet point him either rightor left on the empty street, he has no particular destination in mind. The journeyhas never mattered less to him when he walks with the understanding that if hewere even to cover a million and a half miles in his lifetime, he will carrythe weight of her, gladly, on his shoulders until there is nothing left of himbut dirt and dust.

For now, Suga suffers only the small burden of his foldedsoul in the second pocket of his backpack, and heads for the end of his mailbox,ready to burn.

Tanakahurrieddown the aged pavement, flanked by two streaks of trees and cluttered foliage.Twice he had clipped the tip of his shoe against a crumbling stone, but he onlyclutched the parcels in his arms tighter against his chest and picked up thepace. The horizon beyond the tree-tops was beginning to deepen; the earthytangerine colour of impending dusk had slowly given way for the diffusion ofblue into its vibrancy, and soon, if Tanaka didn’t hurry, he would find himselfswallowed by the shadows that even streetlights couldn’t touch.

There was a healthy layer of brittle leaves thatblanketed the path ahead. From what he could notice, there must’ve been fewvisitors to walk along this mountain trail in a long while. After all, nothing remarkablewaited at the summit except for a view over his town, which one could find mucheasily on a lower hill.

However, this had been the one she had chosen, the oneshe had frequented, and the one Tanaka had brought her ashes up to long ago andscattered before the winds could die down.

If he had a choice, he wouldn’t have chosen this dayto have anything scheduled. There was enough racing through his mind withoutthe pressure of other people, all convivial and pleased to see him and waitingto hear his stories. But he would be there for Noya’s celebration—just this oneexception—even if he would be struggling to make it on time. Tanaka wasn’t surehe could take disappointing two people at once—and the fact that neither wouldblame him, both being far too good to do so, stung even more.

He reached a small ledge that jutted out directlybelow the sharp summit without losing much breath. It was a narrow stretch ofsoil that allowed only three people at most to rest on it at a time, andunsupervised the weeds had begun to spring out from all four corners, stealingwhat space they could. Carefully, Tanaka set down his jar of flowers and hisother two parcels down against a flat rock and tugged on a pair of gardeninggloves. It wasn’t an easy job, with his waist bent and legs squashed togetheras he yanked out fistfuls of weeds and wild daises. They weren’t muscles heused regularly, and no matter how often he soaked up the sweat that pooledabove his brow, there always seemed to be more grime and dirt that came fromhis gritty gloves. However, he took no breaks until they were all gone and, intheir stead, a small mound of discarded foliage which Tanaka kicked off theside of the mountain in one go.

It looked much better now, more recognizable and much cleaner,as she would have liked it. Tanaka took a seat cross-legged in the centre, andslowly unravelled the packages by his feet.

It made no sense at all to be careful with them, asthey were meant to be left on the mountainside for her, free to be battered by thewinds and rains, but Tanaka’s hands shook all the same when he pulled out athick, parchment-like envelope and a small photo album that sat snugly in hispalm. When he had been putting it all together, the stack of notepaper seemedto grow uncontrollably, scribbles running rampant across the never-ending pagesand he had been worried they wouldn’t fit into the envelope he had madehimself. Now, they seemed so disappointingly small, barely even larger than therock he’d rested his flower jar against, and not for the first time, a sense ofoverwhelming shame took over him.

She hadn’t liked flowers very much, either. Theylooked too much like aliens, she’d said to him a long time ago, nose wrinkledas Tanaka laughed over his embarrassment when he’d asked if she’d like someroses for Valentine’s day. They wilted far too quickly and attracted too manybugs. If she had been a flower, she’d insisted, she’d not very much like tostay in someone’s home with her legs cut off either. Tanaka had given herchocolates instead, and she’d appreciated those much more.

Chocolates were much less suitable for the outdoors,however. He couldn’t very well leave the packaging and all for a year, knowingthat it would simply blow away into the distance and become litter for somebodyelse to solve. And if she had reached his age, most girls—or women, now, hesupposed—would have received dozens of bouquets and hydrangea clusters from relationsand colleagues. It was what would happen, what should have happened, and Tanaka wanted her to have everything thateveryone else did. Even things she disliked, he needed her to have the chanceto dislike them, to complain about them, to toss them into the bin of her ownvolition with her wrinkled nose and curled lips.

Sometimes he felt incredibly selfish, like when he setthe flowers down beside him, overlooking their neighbourhood. The flowers he’dchosen were his own favourites, in his favourite colour. The jar he broughtthem in had been a gift from his sister, and he’d thought they matched. Thephoto album he had brought was small but thick, and filled with activities heenjoyed, with moments that he’d experienced, and with the people he’d chosen toshare them with. He’d wished for her to be there, picked out the ones that hethought she’d appreciate the most—but he would never know now. Each photographhe snapped he had her in mind, riding the moments with a leg on each side, notquite unhappy yet not quite satisfied. These were all moments he hadn’t livedto the brim, all moments he’d forgone appreciating in favour of remembering hisloss.

The letter, which had felt so relieving and so rawwhen he’d written it, now sat browned and jagged on the bare soil. It was fullof his emotions, his memories with her, all the things he wanted to say andstill said whenever he had the chance to.

She had no letters to send, no words to share, and nomemories to relive. From the very first moment, Tanaka had only lived forhimself. He’d let her—he remembered with piercing clarity his fear and hisrelief when he’d missed the feeling of the car running over his skull—he’dturned back and wanted to vomit when he saw her lying there on the ground withher arms bent at the wrong angles and her eyes wide open in terror. He’d beenthe one everyone comforted, the one everyone felt sorry for and pitied. He wasthe one his teammates cried for, and he was the one they’d tried cheering up.

All while the last thing she ever knew was fear, fearthat clung to her eyes in a film, a wordless scream in her shattered jaw thatTanaka will never hear and will never have to again.

He had it easy, hadn’t he? Even then, facing the sheerdrop only a few feet away from where he stood, he dared to listen to the callthat beckoned him towards it. It sounded like laughter, and it sounded likecowardice. She never had a choice, not like he did, and if he was a biggercoward than he already was, he’d be tipping himself over the place she’d lovedto frequent most, flaunting his choice in her face.

This small patch of ground fit for a two-personpicnic, there was no marker and no grave upon it. There had been no traces oftheir activities here, no remnant that said, ‘she had been here, and this placeshe had loved’. The offerings Tanaka had brought her were layers of his ownguilt and grief that he lay upon her memory, on the grave of himself, who hehad been and who he could be; her ashes had long left this place, and if shecould love it still, she wouldn’t have loved him then.

When he took a step back from where he’d left hisgifts, they looked terribly small and insignificant in the face of the viewbehind them. He took a deep breath, holding back the tugging impulse to launchthem off the mountain too, and forced his feet one in front of the other, allthe way back down the mountain trail.

It was ironic, then, that he’d made it impeccably ontime for Noya’s party. Not that his oldest, closest friend had organized it, ofcourse, but it was in his honour for getting on the national team, and Tanakarummaged around in his gut for the sincerity he’d stored away for the afternoon.He found Noya waiting for him in a quiet corner, his lower lip nibbled raw whichbetrayed his otherwise gallant expression.

“Thanks for coming,” Noya said immediately and jumped upfrom his seat. Tanaka found his arms gripped so tightly that they were goingnumb within seconds. “How are you holding up?”

Tanaka smiled and was alarmed with how easily hecould. “Better.”

“I—that’s good to hear. You’re welcome to stay as longas you want, obviously, but—you don’t have to. It’s already fantastic to seeyou.”

Not many people would share his sentiment, Tanakaknew. It wouldn’t look very sporting of him if the guest of honour’s bestfriend vanished before anyone could even say hello. He didn’t want to make itany harder for Noya than it already was.

“It’s fine,” he said. He shook his arms free of Noya’svice-like grip and patted his friend’s shoulder’s firmly. “It’s your evening,and I’m here. You don’t have to worry about a thing.”

Noya’s expression remained grim, unconvinced. “Yeah,like saying that’s gonna make me. I meanit, Ryu. I’m not talking it up either—there’s like, a freaking mob out therewaiting for you.”

“Me?” Tanaka was surprised. “The hell? It’s not my party.”

“Dude, you’re like a unicorn. Do you know how rare itis to see you at parties and gatherings like this?”

Itused to be very often, they both knew, but neither saidanything. Tanaka reached out and spun Noya around, pushing him away from thedim little alcove and towards the doorway. “I’ll be alright.”

When Noya stayed grim, Tanaka sighed. “I’m damnedhappy for you, and I’m not gonna ruin your night. You can get me as fucked upas you want as your present.”

“I don’t,”Noya grumbled, but had relaxed under Tanaka’s hands. “Okay, only if you sayso.”

“I say so.”

Tanaka had every intention of keeping his word, evenif Noya didn’t seem to believe him. Undoubtedly, he was going to have a set ofeyes fixed on him the rest of the night. To set an example, he stepped aheadand into the massive living room, letting the horrendously loud music drown outNoya’s complaints. Come on, hemouthed with a familiar grin, and slipped into the crowd of people in search ofa drink.

He’d only managed to locate the make-shift bar when agirl, a few years younger than him from the looks of it, appeared shyly infront of him as if unsure of whether he was going to barrel through herregardless. He didn’t, naturally, and paused to look down at her asunthreateningly as possible.

“What’s up?”

She threw a glance over her shoulder at something andrefused to meet his eyes.

“I—I’ve got a friend—and, uhm, she’s glad to see you?”Her inflection shot up at the end of her sentence, and she looked a littlefrustrated with herself. Tanaka smiled.

“Thanks.”

“Only,” she bit her lip, but soldiered on, “you don’treally come out to drinking things, y’know?”

“Yeah, I know.” He shrugged. “Sorry, I guess?”

She looked startled by his apology, and finallyglanced up. Immediately, he could tell that she was a few years younger than hehad initially assumed. “Oh, I mean, you don’t have to apologize. My friend, she’s—she wants to know if you’d like to graba drink with her.” She jerked a thumb over her shoulder and Tanaka looked atwhere she pointed. There indeed was a friend, sandwiched in-between a smallgroup of four with drinks already in hand and chatting away. She snuck a peekat him and flushed and turned when he caught her looking.

He turned back to the girl in front of him, who was agood head shorter than he was. She seemed much more at ease now that hermessage had been delivered and no longer stood as if waiting her execution.

“I think your friend might have more fun with herfriends than with me,” he said as kindly as he could. “I’m not looking foranyone at the moment, sorry.”

She blinked. “Not even a drink?”

“Nah.” He gave her a pat on the shoulder beforestepping around her with a gentle smile. “Please tell your friend sorry fromme. I’ve got a girl waiting for me, you see, and I’m afraid that’s not gonnachange.”

For the first time in his life, Bokuto Koutarou crouched, soundless, and scrambled for words that haddeserted him.

She lay in his arms, face scrunched up, eyes pressedshut and her mouth twisted in a quiet groan of pain that he was helpless toease. His arms, for all the strain they could withstand, were useless,trembling, and his palms that were coated with blood and sweat could only shakeas he cradled her head on his lap; he wanted to press her close, to soothe hersuffering from broken limbs and cracked bones he daren’t look down at, butabove all, he was afraid that any movement would hurt her more.

Bokuto realized that he was sobbing out loud when shestrained a hand up to brush against his cheek, and smeared a grime coveredthumb against the wetness that clung to his lower lip. The sudden sting of salton a cut startled him.

When she spoke, it sounded as if she did throughknives.

“Are you hurt?”

Bokuto watched as she attempted to crack an eye openbut winced, closing them again with a shaky breath. “Are you hurt?” She repeated.

His face crumpled as he rifled through everything thatrushed through him, none of them urgent about his own wellbeing in theslightest and bent down as low as his back would allow him to press his faceinto her hair, caring nothing about the dirt and salt and the heavy taste ofiron against her temple.

“Please don’t die.”

“Kou—”

“Don’t die.Don’t die.” He could hear his voice from a mile away, from a broken little boykneeling on scorched tarmac and here he was, opening his mouth and letting theshattered words flow. “Tell me you’re going to be okay, please. Please. I’m so sorry. I’m so fuckingsorry. I love you, I love you. Please stay with me.”

“Hey. Hey.”It sounded painful to hear her speak, her breaths rattling in her chest, andBokuto wanted nothing more but to hold her close, so very close that his life couldleak into her frail, twisted body. Forcing his eyes shut, he pictured it withall his might; the frantic, pulsing heartbeat in his chest spilling over intoher, past her broken ribs, and clutching at her beating heart so that it couldn’tgive up.

“Koutarou,” she said again, and he nodded mutelyagainst her head. He felt a hand slip into his, even if it was slimy and wetand too difficult for him to hold onto forever. “I’m gonna be okay. Kou—Kou,listen to me, love. I’ll be alright, okay? Kou?”

He kept on nodding, rocking back and forth on hisknees with her shallow breaths moist against his shredded shirt. She gave alittle sigh, one that came from deep, deep down, sounding as if she was veryexhausted indeed.

“Don’t cry for me, Kou.” Impossible. Bokuto gave athick sob and attempted to calm his breaths anyway, because he would doanything she said—anything. She could have demanded he tear his organs out oneby one to replace hers and he would’ve done it without a sound. “We’re gonna beokay. I love you so much, and we’re gonna be okay.”

From far away, Bokuto’s narrow world stretched out tothe sound of sirens that seemed to be spiralling closer and closer. He felt wrenchedin half; he wanted to hold her here against him for the rest of time where hecould feel her in his arms, still warm and breathing and saying all thosebeautiful, sweet words from her bloodied, parched lips. He also needed thoseambulances here ten minutes ago, packing her safely into the stretcher so thathe would be sure that she’d live, that she’d be fixed as soon as possible, andhe would wait by her door for as long as it took until he heard the news hewanted to hear.

He wanted to hear her laugh as she took everything sovery facetiously, making light of all the things that should be solemn. Just you wait, he could hear her sayingin his head as she craned her neck from the stretcher, once I’m out of surgery, I’m going to be in even better shape than youare. He would then wait, twiddling his thumbs, until she would come outagain, all spick and span, a million-watt smile on her face as she grinned athim, cradling his cheeks in her palms. She would lean in close, her breathtickling his lips, and she’d say warmly to him, I’m right here. I told you so, didn’t I?

“Kou?” He heard her voice again, and he knew that hewas back on his knees in the middle of the street with her soft, silky hairmatted against her forehead from the gash on her temple. “Kou, Kou,” sherepeated weakly, and he leaned down and slotted his lips over hers as desperatelyas he could. He wanted to taste her for as long as he could, to press down herthroat all the things he needed to hear from her, to stop himself from cryingall over again. She had no energy left to kiss back, but he could feel her lipscurl into a smile underneath his.

“The ambulance is here,” she told him quietly andsqueezed his hand. “Everything’s going to be fine.”

Bokuto wasn’t sure if he could be brave enough tobelieve her, but time had run out for him to decide when a strong, firm handgrasped him by a shoulder and tugged him gently away. He was taller and widerthan the EMT that stood behind him when he got to his feet, but all he could doto help was to obediently drape himself with the blanket they handed him andstand to one side whilst they shifted her onto a collapsible stretcher.

“I’m going with her,” he said stonily to one of theuniformed men, and they cleared out a seat for him inside the ambulance with understandinglooks that carved up his insides with something hideous.

The whole affair lasted an unfair five minutes. Bokutowatched with wide, red-rimmed eyes as a flash flood of professionals andspecialists had waltzed onto the scene with their tools and bobs and just likethat—those pockets of timelessness as he’d cradled her jagged skull against hisshaking fingers, they were nothing—the ground was wiped clean of them, of howmuch he’d cried and how much she’d spoken to him with that charred voice andlidded eyes. When he reached out for her mindlessly, dull from the anxiety, thewoman next to him in uniform and looking loathsomely put-together, gripped hishand before it could make contact.

He snatched it back to his chest and glared at theground, wounded.

“She’s in a pretty volatile state,” the EMT said,sounding sympathetic. Bokuto shifted to stare at the prone body instead; herchest rising and falling so faintly that if he turned away for a second itmight fail in his absence. He kept his hand held close. “You can touch her onceshe’s out of the ER.”

He said nothing. Quietly, as privately as he can withthe small, struggling embers of hope, Bokuto relived in his mind her grin andher words against his cheek, murmuring: I’mright here.

The next time he arrived back into himself, forciblydragged from the depths by a firm shake, Bokuto was informed that it hadalready been a day since the accident. And perhaps he could accept such adescription, if only he didn’t believe that every single broken bone in herbody was deliberate, intentional and a heavy enough weight to be foisted uponon his own conscience. The doctor, whose hands were digging harshly into thedips of his flesh, asked in a concerned voice whether he was alright, and if heneeded a bed to lie down in.

“I’ll lie down when I see her,” he snapped, rough andangry.

The doctor jerked away and eyed Bokuto like the wildanimal he felt very much like.

“In here,” the doctor said. He didn’t touch Bokutoagain, but like a wraith without anything to cling onto except for the emeraldshimmer of the afterlife, Bokuto followed with mute feet.

Her family was situated in the otherwise generouslysized room, and they broke from their stations like a wave upon a dam, takingturns embracing Bokuto with watery smiles. They were trying their very best, hecould feel through his numbness, and her mother had crept up on him unawaresand had his pale cheeks grasped in her palms like a talisman. Bokuto did hisutmost to meet her eyes, but neither of them was deceived that his nicetieswere anything more than that.

“We were worried about you,” she said slowly, as ifspeaking to a jittery bird, “you’ve been out cold on the hospital bench andrefused to come in with us when we asked.”

He couldn’t recall a single moment of that, only howhis fingertips ached from where he’d bitten them down to the flesh. She lifteda hand to stroke his grimy hair like a child, with her other cupping the backof his neck in case he slipped through them again. A staggering pain clenchedhis throat shut and Bokuto had to swallow twice, hard, to be able to hold backhis sharp longing for comfort. The hand behind his neck tightened, and hermother pulled him into a slow, calm hug, rocking him back and forth like he haddone before.

When the doctor spoke, the words only barely madesense to Bokuto from very far away. “Her executive functions are gone,” he saidfrom behind that terrible haze, “her internal bleeding…concussion of thebrain…” He was still being held within a soft pair of arms that seemed to clingto him for hope as heavily as he leaned on them for the strength to stand. I’m right here, the words chantedthemselves in his head, we’re going to bealright. Kou.

“Bokuto?”

Bokuto pulled his head up and searched blearily forthe sound of his name. The rocking had stopped, and held at arm’s length, hewas alone again, the recipient of all the silent stares in the room. Theyprickled on his skin like a hundred needles and he kept his gaze hollow on theface of the woman he loved, the woman he was going to marry, lying wordlesslyin the centre of the hospital bed. If he dreamt hard enough, perhaps those lipswould move, giving weight to their voices he heard regardless.

“The last thing she said was your name, Bokuto.” God, he hated how he could still hear,how he was still there no matter how far he went away inside. How he couldunderstand every syllable from her mother’s mouth, how that stare was kind,bitter and incriminating all at the same time. “It’s what she would havewanted.”

Turning, he watched her coldly. It may have been thatshe couldn’t extend her sensitivity that far, or perhaps it was how far she hadsunk into the heaviness of her own declaration, but she met his eyes withoutseeing.

“We weren’t…always in agreement,” her mother admitted.“It’s…I know this is the least I can do for her. To make up for it all.”

Bokuto didn’t bother to wait for her beseeching look;how she dared to ask this as if it was her choice alone—as if she no longerbelieved that her daughter could make it. As if she’d forgotten those brilliantsmiles, those quiet reassurances and her wintery voice in one’s ear holding allthe answers to the miniature universe Bokuto hid underneath his heart. The roomstood motionless where her monitor still sounded to the rhythm of her pulse,their heads all bowed low and hands behind their backs.

“Bokuto?”

It’llbe alright. I’m right here.

“She asked for you.”

Kou?

Bokuto nodded to the doctor, neck stiff and lipstwisted in a grimace, and offered up what remained of him. He made the callwith barely a sound, a motion that dragged his head lower and lower, and Bokutowalked out of the room as silently as he had entered, leaving Koutarou behindat her bedside, holding her hand and kissing her brow. He left with them gifts;all their lost time and hidden smiles, the wet laughter as she departed thehospital with his hand in hers and hopes that they could be happy wherever theywere now.

In the stale, antiseptic smell of the third-floorbathroom, her blood underneath his nails stayed firmly jammed into the creasesof skin no matter how hard he scrubbed and scrubbed.

She woke up on the fifth day. The room in its entiretyremained unchanged: the heartrate monitor continued to sound its steady, shrillnotes, the birds outside sang their morning songs and the steady breaths of aman drifting in a fitful sleep maintained its weary pace. Her eyelids creakedopen and her mouth opened and closed without sound.

“Hello?”

Kuroostartled awake from his shallow sleep when the hoarse, aged voice groundthrough the peace in the hospital room. As much as his reflexes urged him toleap out of his seat and huddle over her bubble of personal space, the days hehad been sprawled prone and unmoving in the lumpy couch had taken its toll onhis muscles. He managed instead to crane his neck to look, with his heart inhis mouth, and was met with confused, but good-humoured eyes.

“Hello,” he replied faintly, and almost laughed outloud at how ridiculously anti-climactic this all was. While his chest begun toswell against his will, pressing painfully against his ribcage, there were onlyquiet, shy words that hung about them.

“How long have I been out?”

She moved to shift herself higher up the bed and Kuroomanaged to rediscover his limbs in time to reach over and usher her back underthe covers. She gave herself a quick look-over, eyes widening at the lattice ofneedles and tubes hiking up her arms and legs but allowed herself to be pushed.

“I remember a car—” She paused, searching her fingerscurled around her sheets, finding nothing. “But that’s it.” She saw Kuroo openinghis mouth, and she added nervously, “Does my insurance cover this?”

He snorted, and his chest blew up more when a smallsmile teased at her worn face.

“If your insurance doesn’t cover a car-crash, I don’tknow what it would.”

“Being murdered, maybe?” She suggested, giving it agood think. “Permanently maimed?”

Her hand lay lax on the sterile sheets and Kuroo hadto hold himself back from gripping it so tightly that all the connectors andimplements fell off. He watched her pulse swell and ebb against the long needlethat drank from her wrist.

“I’ll let the doctor know, if you like,” he said.

“No thanks.” Her smile brightened into a tiny beam athim before it faded, and she turned her head to gaze at the tree that grewbeside her window. “They might send me off to the psych ward, which’ll be evenworse.”

“So very conscious of your insurance,” Kuroo murmured,and watched as a little light returned to her eyes. Her hand lay on top of his,her skin pulled taught over her bones from dehydration, and with purpose andthe lightest touch, he traced rings along each digit, twirling his tremblingfingers over hers. Still, she watched the leaves flutter through the autumnwind, her private room seemingly too small for her silence and his presence,which went uncommented on.

Kuroo knew this tiny little room better than his own.None of the nurses nor doctors dared touch him when they had first assigned herthis part of the ward, and thus Kuroo sat, motionless and vigilant at herbedside for five days, occasionally alternating between the hard, foldablechair and the musty sofa tucked into the far corner beside her bed. The openwindows were his only source of time; his broken hours of sleep haunted bysounds of her bones cracking, her muffled whimper and his own scream—and therelief in her eyes, unfocused but aware, when she saw him alive and untouchedbecause she had taken his place. He saw no point in waking the floor with hisown shouts and woke often to his lips dry and sealed shut with caking spit,stumbling afterwards into the hallway bathrooms for a hurried wash.

“Would you like to check your phone?” He asked,conscious of her mind wandering through the paths outside in the rehabilitationgardens from her blank, lost expression. “I’ve had it charged.”

He hadn’t allowed it otherwise. It was cracked, ofcourse, from the impact, and the screen was completely shattered. Still, he hadit plugged in day and night into the only spare socket in the room, minding itin case someone called. Many did, of course, but on his, which he had let thebattery drain out of in favour of hers in case her family attempted to reachher.

But situated in another country, they continued theirlives unaware of her situation when she had put Kuroo as her emergency contact.And, from her lack of concern, Kuroo guessed that she at least remembered that,and didn’t remind her of it again. He gave her hand a final squeeze and made tostand.

“I’ll go and let the nurse know you’re up anyway.Better sooner than later.”

“Kuroo,” her voice came haltingly from where she wasturned away, and Kuroo stopped where he was. “Do you know how I got into anaccident?”

It was a minute before he could speak, and even then,he sounded scratchy even to his own ears. “What do you mean?” He asked slowly.

“I—I’m missing some bits.” Kuroo came to realize, whenher voice trembled, that instead of dreaming, the reason she had turned awaywas because she had been busy fighting the panic that pushed against hercontrol. “I mean, I know it’s just an accident and a lot of people get intothose, but I—I can’t remember. That, and a lot of other things.”

“And me? Do you remember me?” The sound of his voicecracking was louder in his head, and he was glad she was turned away, so shewouldn’t have to catch sight of his pale face, twisted and sour.

“Of course,” she said, sounding surprised. “Kuroo, Isaid your name, didn’t I?”

She did, she had, and Kuroo’s throat was too closedfor him to say anything. He dragged a hand across his eyes furiously, one handon the doorknob and his breaths coming in ragged, heaving sighs.

“Kuroo,” she repeated quietly, and facing the door theentire time he imagined her speaking the wrong name softly into her hands, eyesdowncast and lips turned into a frown. “Thank you for being here when I wokeup.”

He felt a rush of anger, completely irrational anger,surge through him and for a moment he wanted to whirl back and shake her untilshe started to cry for all the pain she’d put him through. Until she took backthat inane sentence that was an insult to even be voiced out loud—not afterwhat she’d done for him, not after he’d watched her die for him, and here she—she “thankyou for being here-d” him. He’d be there through death for her, and beyond,and he if he could, he would shout it at her until she remembered every singleagonizing second of it all.

Kuroo could only nod mutely and slipped out into thecorridor, the door sliding shut with a tinny air-tight squeak behind him.

He surprised himself with how dispassionate he soundedwhen he informed the front desk of her situation. “She’s missing somememories,” he said calmly, as if reciting a PowerPoint. He kept his hands inhis pockets and his expression mild even when the nurses watched him for toolong. “She seems okay otherwise. Will you let me know if you need me foranything?”

They didn’t ask him where he was going, even as theyhurried into her room, cluttered with a mess of both their belongings that hadsurvived the impeding car. For such a large facility, there really werehorrifically few places where he could wander. That room he’d almost built anew house in these past few days had his absence filled almost effortlesslywith her vacant smile and sparkling jokes that were there to zing all the awkwardness away, and Kurooknew any more of that and he might kill a man.

The double doors to the rehabilitation gardens wereunlocked, and Kuroo walked right through them. The tree she had been soenraptured with by her window stood out like a sore thumb in the centre of thesparse park. He sat on the bench, ignoring the blanket of leaves that had piledup along the wooden slats. Kuroo attempted to summon up the grief he had criedsilently through the first few nights, if only to remind himself of a purer,less complicated brand of suffering. Where the dip in the sofa he’d left aftersleeping there for so long would mean nothing to her, Kuroo turned his closedeyes to the sky and waited for a lost sorrow to come upon him as surely as hersummons might not. It was a long time to wait, for there was a hollow in hischest where he’d cried everything out, each growing loss manifesting only as anache, calling out to him that nothing would ever happen again.

If only that were true. If only the leaves crunched upand falling apart underneath his palms would pause and return to the way theyhad been a few seconds ago. If only anything he said or thought or wanted tohit would freeze in time and slowly drag themselves back into nonexistence aminute later. He hadn’t realized that his brittle rib cage, so easily shatteredby blunt force, could harbour so much resentment for something he’d loved soguilelessly earlier that morning.

If only it could go back, turn back, his breathsforced back into his lungs where he’d expelled them—he could allow himself to loathethe image of her sprawled in her hospital bed with her pointless thank you, and her kind, gravelly voicecalling him Kuroo. And then, a minute would pass, and he could love her onceagain in the way he wished he was still allowed.

He stayed where he was, belonging nowhere, until thesky had dimmed beyond the overhead of the hospital. It was only until the soundof gravel crunching that disturbed his trance, a pair of harried trainers hurtlingin his direction that was far too fast for his liking. Kuroo cracked open aneye and watched he nurse marching towards him, perspiration seeping into herwhite collar. They must’ve looked all over for him as he’d forgotten his phonesomewhere in that god forsaken room.

She was still panting when she spoke. “Mister,” she saidtetchily, “you’re still her only emergency contact. If you’d like to come backin, the doctor would like to give you a prognosis and inform you of the follow-uptreatment.”

He wondered how much she remembered, but the nurse hadrevealed nothing about her reaction. Who in their right mind would leave afriend, no matter how close, as their only emergency contact? No questionsabout that precious insurance policy?

The nurse tapped her foot loudly on the pebbled path,and Kuroo met her eyes, glare for glare. Her fringe was pasted to her foreheadwith sweat, and staring at it, he supposed he’d given her enough trouble forone evening, no matter how disagreeable he felt like being.

“Alright,” he said, and followed after her.

- - -

“Thanks for today,” she said, always quietly, andalways shyly. “Again.”

“My pleasure,” Kuroo said. “We on for tomorrowafternoon?”

“Ah, yes, of course.” She pulled out her phone,scrolling up the calendar she always had open and tapped at tomorrow’s date.Kuroo spied four other bullet points scheduled in, and his name was highlightedin lilac, sat snugly in the middle of the list. “The tea gardens?”

“The tea gardens.”

“I’ll dress accordingly, then.” Kuroo had to bend downslightly to catch her tentative smile, directed fully at her phone and herfingers curled around the glass edges of it protectively. He wondered if toher, he was still something to be protected from.

He straightened back up and slotted a nice, kind smilein place. That seemed to bring her out of her shell a little, and he threw astep back into the mix, so that she’d be able to stand up straight instead ofhunch over her electronics as if she wanted to delve into them.

“I’ll text you,” she said as she waved him goodbye.“Thanks again!”

He waved back and waited for her back to recede out ofview in the crowded pedestrian crossing. The doctor would be pleased with theeffort he’d been putting in. Kuroo could envision his nodding head, thosehideous glasses covering half his face and his pudgy fingers tapping away onhis iPad. He didn’t care if he had a bias against him; he was a volleyballplayer, not a priest.

His phone beeped in his pocket, and he took it out.

Ihope it’s sunny tomorrow!

At least someone did; it was no-one Kuroo remembered.Occasionally on these miniature visits down memory lane-dates, he would takethose pockets of silence and envision himself walking away from the nurse thatafternoon. Marching out of the garden and never to return. He could go anywherehe liked, sit alone at the places where she’d take him with her knowing grinsand caustic humour, kicking him under the table and leaping onto his back inpublic and tickling his sides.

She wouldn’t be peeking under her eyelashes at him.Calling him Kuroo, sending him textsthat were meant to be nice, wringingher fingers in nervousness and stepping on those eggshells around him as if hewasn’t too far heartbroken to really care if she hurt him a little more. He’dbe able to grieve properly, to go over the pictures on his phone withoutthinking about how that face was still walking, talking and smiling, but to aKuroo that was half-baked in her memories, as she went about her days with onlyhalf of the affection, half of the liveliness. She wasn’t lesser. She wasn’tmissing any part of her. She was simply different, having vanished bits of thepast that made her into the woman who had leapt in front of that car for him,who had cried for him and who had laughed with a punctured lung for him. Thoseempty spaces had been so swiftly filled with new, unrecognizable parts, thatKuroo had almost reeled from the backlash.

‘Ihope it’s sunny tomorrow.’ She hated the sun. She might’ve hatedit still but had forgotten that Kuroo knew that about her. After all, who wouldwant to go to a park in the rain?

Kuroo knew he would regret thinking it. He loved her,he loves her still, and he would continue to love her until his last breath.But what was fundamentally her had been crushed underneath those wheels thatday and had left him all alone on the operating table. He would regret thinkingit. He would regret thinking it for the rest of his days.

If he couldn’t have been the one to die for herinstead, then he wished that she’d never survived at all.

#sugawara koushi#tanaka ryuunosuke#bokuto koutarou#kuroo tetsurou#haikyuu!!#haikyuu#haikyuu scenarios#haikyuu imagines#female original character#sfw#i writes the haikyuu

65 notes

·

View notes