Note

Self-portrait with spanish flu and self-portrait after spanish flu both by edward munch might be interesting to do since we're obviously in a pandemic

I’ll definitely look into it! Munch is such an interesting character in art history, one of my all-time favorites.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This overturned urinal has forever altered the course of the modern oeuvre, more so than Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, more so than Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych. That statement could have been plucked straight from some absurdist pocket universe of Douglas Adams’ imagination, yet it is an unshakable truth, a cornerstone necessity in understanding the spirit of art as we know it today. It’s dumb; it’s brilliant; it’s beautiful; it’s insulting; it’s Dada frontman Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain.

Dadaism originated from the tempest of the emerging 20th century. With every exciting innovation such as the radio or aviation came an accompaniment of tragic perversion from the corruption and incompetence of old authority to the eruption of the most expansive and destructive war the world had ever seen. For artists in the Dada movement, the response was reactionary, to be the anti-angst in their societies so permeated by it.

Their mission was almost paradoxical in nature: to combat chaos by inciting it. Even the name ‘Dada’ stems from a mythos of randomness. The story goes that Richard Huelsenbeck supposedly stabbed a letter opener into a dictionary, and the tool was lodged into the word ‘dada’, a French colloquialism for hobbyhorse. There exists an endless catalogue of anecdotes not unlike this one that showcase the colorfulness of the movement and its characters, but in nothing else is the essence of Dadaism more concisely and perfectly demonstrated than in Duchamp’s Fountain.

Fountain is the quintessential readymade, a medium in which a pre-manufactured, and often mass produced, commodity is considered art simply because the artist deemed it as so. Forget the typical formalities and considerations put into the worth of art. There’s no rarity (even this photograph is the a reproduction of the mysteriously vanished original), no technique, no especial quality that puts Duchamp’s urinal above all others. The lowly and humble existence of the bathroom fixture soon became the main talking point of the great schism in ideology that would usher in a new wave of contemporary creativity.

Duchamp wished to test the limits of artistic radicalism, to test the true merit of the apparently nondiscriminatory idealism of his followers. He sought to make New York City his ambitious pet project and mold it to his image of what Paris should have been and everything it failed to be. In the newly founded Society of Independent Artists, the constitution specifically mentioned the acceptance of all submissions from its members, and yet when Fountain was submitted under the alias of R. Mutt (Duchamp feared the influence of his reputation), the piece was rejected for being too crude; it is after all, a goddamned urinal.

In this new age gray area, Duchamp had finally discovered some boundary to what art could be. Since its controversial debut, Fountain only found praise and popularity decades later with the emergence of Pop Art, Surrealism, AbEx, all schools of thought that cited the tenets of Duchamp as inspiration for questioning the concept of art.

Though just a simple urinal in physical form, Fountain challenged what it meant to be a creator, what it meant to view things in perspective, what it meant to be original. The original piece was never did find appreciation in its known lifetime, but the sacrifice represented by that one standing toilet made it possible for all other things of strange beauty and raw ugliness that followed it to have a chance in the eye of the beholder.

#art#art history#dada#dadaism#duchamp#marcel duchamp#fountain#urinal#modern art#new york#american art#contemporary art#blarty#helloblarty#20th Century#20th century art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty almost looks like something out of a fever dream, some Dalí landscape mistakenly displaced into the real world. Under the sweltering Utah sun, you might even believe it were a mirage. The form and plain existence of Smithson’s earth art is something stranger than fiction, and I would even argue, something greater than fiction. Visiting the landscape one day takes its place of pride on my bucket list for the Spiral Jetty represents one of the noblest virtues an artwork could ever embody: putting the life before the art.

Located in a quiet corner of the Great Salt Lake, the Spiral Jetty throws a gauntlet before its travelers to complete an often underestimated, grueling pilgrimage. No matter how prepared a journey may be, there are undeniably inevitable hitches along the way that can stall or even compromise the mission. From nebulous directions to the creeping sense of anxiety from hours on the road, the trip to the Spiral Jetty is a deprivation chamber of sorts. Confined with only the time, company (or lack thereof), and space of your vehicle, should you venture to Smithson’s scroll, you will be forced to confront your identity across deep and primal lines. There are truly few experiences quite like it that can cut through the masks of formality and inauthenticity we put on to survive every day, to homogenize with our everyday.

Due to the increasing severity of Utah droughts, the Spiral Jetty is now clearly visible for the majority of the year, but prior to the shift in climate, Smithson’s magnum opus was largely covered by the lake’s overflowing waters. Everything from the vibrant pink aura from the surrounding crustaceans to the trodden path itself was completely obscured. So why spend unrecoverable hours on the trek? Why sacrifice meaningful relationships and virtues of self-assuredness for a reward so seemingly arbitrary?

It’s that risk, that raw vulnerability alone that justifies the journey. The Spiral Jetty is little more than a cover for a personal odyssey. For better or for worse, the landmark demands its travelers to meet it halfway in the spiritual aspect of the adventure. While the natives and terrain provide enough to juggle with on the way there, what the image of self-discovery looks like, is an abstraction painted entirely within your own mind.

Images on a screen simply don’t provide justice to the true nature of the Spiral Jetty; while we are living through an incredibly trying time in world history in which vacationing should be amongst the last of our priorities, the difficulties and time we have unexpectedly inherited is an amplification of the concepts Smithson’s piece is so emblematic of. Periods of crisis call for both solidarity and safety. We should all adapt new lifestyles to curb the impact of this threatening disease in ways that don’t discount our most fulfilling connections. Above all else, we should remember that we are all traveling on the same path to the same jetty together. With that in mind, it’s also up to us to determine what the road there will look like, how it will be remembered.

#robert smithson#smithson#spiral jetty#utah#great salt lake#art#art history#earth art#modern art#blarty#helloblarty#american art#jetty

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

639 years. That’s 233,235 days, 20 billion seconds, roughly 9 lifetimes. Even when put into specific and deliberate numbers, such a timeline is hardly fathomable to us. It is no new thought that time, much like art, is relative, but is it so simple to enhance the legacies of our creations by prolonging their mortality? If so, what’s the date of expiration? How long would it be until the parts of us we try so desperately to leave behind are invariably forgotten and eventually die?

A fascinating project that might shed some insight on such heavy questions is an ongoing performance of John Cage’s As Slow as Possible in the Halberstadt Cathedral of Germany, or more accurately, a 639-year performance of John Cage’s As Slow as Possible in the Halberstadt Cathedral of Germany. The context behind this installation’s set up can seem deceptively contemplative, surely such a project must be the brainchild of some deeply brooding cliché of an artist trying to communicate a sentiment the general public just wouldn’t get. How the Halberstadt performance came to be is much more of an Occam’s Razor type deal. A curious coalition of composers and musicians saw the potential in the practical permanence of the organ to perform the renowned Cage composition truly as slow as possible. The determination of the location and the seemingly random timeframe of 639 years was equally as straightforward. The Halberstadt Cathedral is home to the world’s oldest, permanently installed organ, an achievement the institution laid claim to for 639 years prior to the start of the music project.

As simple as the Halberstadt performance’s motivations were, such an ambitious installation cannot help but garner questions concerning its greater significance to the art world. Of the many conversations sparked by this longstanding sentinel, I’m most excited about the performance’s implications on the death of art. Assuming perfect maintenance, this truly will become a unique capsule of change no generation for a considerable amount of time will be excluded from. Comparable projects that come to mind are Manfred Laber’s Time Pyramid and the Great Mosque of Djenne.

While this brief series has been an extended and emphatic discussion on the death of art, the conversation which surrounds what keeps art alive is magnitudes more complex. While the whole of the potential prognoses that may kill art are infinite and innumerable, in the very least, specific cases can be discussed, dissected. What perpetuates art, the intangible factors at play, are not so obvious as the killers of art. But I think whatever it may be that keeps our art alive, comes quite close to the special X factor of the Halberstadt performance, the Time Pyramid, the Great Mosque. In one way or another the traditions, the faithfulness and flexibility of tradition, that surround these three pieces possess pass on a sense of relevance to the future. Through their existence, our importance is inherited. Of course, there is no guarantee of how the ideals, the hopes, the concerns of today will be received tomorrow, but art has never been a field centered around consistency. The illusion of a “forever” projected by this particular rendition of As Long as Possible is evocative, tempting. Whether we speak of who we were yesterday, who we are now, whoever we may be tomorrow, such a concept will always be tantalizing to the whole of humanity...such an idea may even be enough to stave off the infamously daunting thought of the death of art.

#halberstadt#john cage#piano#contemporary art#modern art#art#art history#helloblarty#germany#piano music#death of art#blarty#organ#organ music

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sandro Botticelli’s La Primavera is hailed as one of the greatest pieces of the Florentine Renaissance. Currently housed at the Uffizi, the painting strays not far from its origins in the old master’s studio. La Primavera is true to its name as a blizzard of Greco-Roman and 15th century Italian symbols of love, peace, prosperity, and most importantly, life were lavished upon the canvas. The work brings with it a new magnitude to the label “masterful” as Botticelli showcases his sophisticated grasp over the human anatomy and botany, with La Primavera containing at least 138 accurately depicted species of plants. So how does a painting such as Botticelli’s Spring, that is brimming with so much life and celebration for human exceptionalism, act as a harbinger of the death of art?

Best known for his paintings The Birth of Venus and today’s focus, La Primavera or Spring, Botticelli was a favorite of the Early Renaissance. Though Botticelli was one of the talented Florentine artists fortunate enough to be in the generous employ of such institutions as the Catholic Church and House Medici, he was certainly the black sheep of the group. Whereas other Medici painters and sculptors such as Donatello or Michelangelo were constantly experimenting with and redefining the western canon, Botticelli was unique in that his style dwelt steadfastly and stubbornly in traditional Quattrocento artistry. Botticelli worked by a doctrine of perfection rather than proficiency, and so his career bears evidence of his noble intent to constantly elevate and refine the fundamentals so many artists that followed him sought to move past from.

Though he founded a comfortable and consistent lifestyle off the Florentine aristocracy’s dime, Botticelli’s piety and artistry were brought at direct odds with each other come Savonarola’s reign over Florence. Authoritarian Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola briefly usurped social prowess from the Medici family in the early 1490′s. Amongst the sea of his enamored congregation was Sandro Botticelli. The first changes to Botticelli’s work eerily paralleled that which was earlier damned by Savonarola in his fiery sermons. Shortly after Savonarola lamented over how contemporary depictions of the Virgin Mary dressed her as a whore, Botticelli’s renditions of the Virgin became noticeably more conservative. His paintings gradually adapted to fit Savonarola’s severe ideal of proper Christianity until art itself became a cardinal sin.

Likely the most recognizable act of Savonarola, the Bonfire of Vanities engulfed the decadence and luxury that practically defined Renaissance Florence in great pits of licking flames. Inspired by the intense insistence of his spiritual leader, Botticelli took some leave from painting and threw many of the pieces he did have into the Dominican friar’s violent show of fanatic spectacle. Though there is no consensus over what became of Botticelli’s career after the few tumultuous Savonarola years, the tangible effect it did have has left centuries of questioning and for some, a faint sense of loss.

La Primavera is one of several Botticelli’s paintings that were fortunate to have survived the supposed purge, but there must be some feelings of inquisition for what happened to the rest and the extent of this body of lost Botticelli work. Personally, I see the mere existence of the question behind the unmourned tragedy of Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities as a true representation of the death of art. As discussed with the Bamiyan Buddhas, remembrance is an integral component of the life of a creation. Without the soul, without the physical aesthetic, what do these lost Botticelli paintings possess but a vague conjecture of once being? Forever shrouded in anonymity, these pieces still have some strange hold, at least on me. They leave an indelible and bittersweet mark upon my impression of existing Botticelli paintings like La Primavera or the Birth of Venus in that I think I will always wonder about what potential, what great capsules of culture, were lost to the fire.

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#botticelli#sandro botticelli#renaissance#renaissance art#la primavera#spring#death#death of art#bonfire of the vanities#savonarola#helloblarty#blarty#quattrocento#birth of venus#painting#oil painting

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What do the Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan, Botticelli’s La Primavera, and a 639-year performance of John Cage’s As Slow aS Possible have in common? It almost seems like the set up of a bad art joke. Except, there’s no punchline here. These pieces may be separated by extinct eras and irreconcilable distinctions in culture and location, but they are inextricably connected through one concept: the death of art. Instead of the usual discussion of a single artist or work, these three pieces will lead an inquiry into the abstract and nebulous idea of what it means for art to die. To be clear, I will be focusing on the most literal aspect of this hypothetical, that being the deformation or nonexistence of a work. Though we traditionally consider art to be everlasting, a message to generations of strangers far past the confines of our own timelines—when movements die, when sculptures decay, when paintings mold—our perceptions and remembrance of those works are irrevocably changed.

In the most literal sense of the term, the death of art is almost always first realized with physical degradation. If you peer closely and imagine openly, you can almost see it. There exists a faint sense of the former glory once held by the Bamiyan Buddhas. Erected in the 6th century, the immense figures were a sight to behold on the middle leg of the Silk Road. In the prime of the Buddhas’ exhibition, their distinctive style spoke volumes to this blended heritage. The high relief sculptures were carved directly from alcoves in the sandstone cliffs of Bamyan with additional details being molded with binding coats of mud and stucco. Atop this base, the Buddhas were lavished with painted on details and jewels to accentuate their air of divinity. They are children of the Orient and the Occident. Both Buddhas inherited Hellenistic drapery from the Greeks, stoic expressions from their Wei Dynasty predecessors, androgynous proportions from Gupta India. The hybrid aesthetic of Gandhara sculpture distinguishes itself from every other archaic school of art as there is an obvious integration of its western and eastern heritage.

We may look at accounts from ancient travelers and merchants to learn of what the Buddhas once were, but the modern perspective on their current status is equally important. The questions we must ask concern how and why the conversation surrounding these Gautama figures has shifted post-destruction. In 2001, the Taliban government, with jurisdiction over the Bamyan valley, detonated dynamite and fired anti-aircraft artillery at the Buddhas for weeks. The bare bones of their original foundation were all that was left. Taliban head Mullah Mohammed Omar ordered the attack on the pretense of destroying iconoclastic figures. While he may have achieved his goal at its face value, in some considerations, Omar only further drove the impression of the Bamiyan Buddhas in the narrative of world history.

Since the 2001 defacing of the statues, UNESCO claimed the region as a World Heritage Site, international outrage fueled efforts against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, and both the art history and scientific communities united as a front to salvage what could be saved of the Buddhas. The tragedy of the Bamyan Buddhas is not unique. Unfortunately, these incidents befall on art in a manner that is as nondiscriminatory as it is consistent. Be it Gustave Courbet’s Stonebreakers or towering Gandhara Buddhas, we have to accept the unsuspecting vulnerability and obliqueness of our creations. If the Buddhas were to serve some sort of parable, we should take away that even if colors are dulled, canvas warps, or sculptures are left as piles of ashen smithereens, the artistry that once existed does not have to die too. Perhaps it will always be missing something, some essence that was one and the same as its vessel, but the Bamyan Buddhas represent every reason why we cannot afford to forget in the face of these crimes against culture.

So if art can live on even with the absence or deformation of its literal presence, what does it take for art to die?

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#helloblarty#bamyan#buddha#buddhist art#bamiyan buddhas#afghanistan#gandhara#sculpture#6th century#6th century art#gandhara art

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What you see before you are vases from Han Dynasty China. Coveted for their craftsmanship, a symbol of ancient oriental ingenuity, national treasures, and copiously slathered in obnoxiously vibrant industrial paint. If it were anyone else who committed such an atrocity, I would be viscerally cringing. But because it was Ai Weiwei, the rebel WITH a cause, the mouth who can never be silenced, the absurdist who is unparalleled in his observations of reality, his Colored Vases warrant a second look.

Art historians and the general public alike have been divided over whether Ai Weiwei’s vases can considered as art or deplorable examples of vandalism in the guise of modern art. In order to understand these perspectives and subsequently form our own judgements, context is necessary. Predating even the start of the orthodox dynasties, pottery is one of the most refined aspects of the Chinese cultural identity. Looking beyond their distracting exteriors, this incredible mastery and experience is evident in these vases.

The structure of these vases are robust and has a distinctive silhouette. In this series, the vases swell in their upper abdomen and taper off in both directions. The tops are cut off with lips that convex upwards, while the bottoms round off upon a circular foundation. The first ceramicists to throw such an unsuspectingly complex and impressive form on a wheel might not have understood the gravity of their accomplishments or even referred to their creations as “art”, but regardless of whether or not they possessed the foresight to predict the massive impact of their work, these first potters ignited one of the most iconic legacies left by any world culture.

Among the first works that are associated with Chinese art are the blue and white porcelain Ming dynasty vases, and even to this day, there’s scarcely any Eastern earthenware that hasn’t been in some way influenced by the legendary Jingdezhen ware. Any pilgrim of pottery has the rocky hills of Jingdezhen on his/her bucket list as it’s hailed as the porcelain Mecca. Oriental porcelain is an emblem of the virtues and merits of Chinese history and is universally acknowledged as one of the most important components driving the country’s aesthetic. Ai Weiwei has drastically altered the image we have in our minds, so it’s not surprising that his so innocuously named Colored Vases incited such a deeply dramatic, jarred reaction.

Ai’s critics were quick to condemn him for the blatant destruction of priceless, irreplaceable artifacts and his ferocious disrespect of his mother country, with the most extreme parties even claiming treason; however, Ai Weiwei had an actual purpose and intention to create these pieces. They are vases, yes, but like the majority of his work, Ai was constructing a mirror. He took a deeply respected image of China and sloppily smothered it. The beauty and the admiration of the vases still linger, but are nonetheless tarnished by this act. To Ai, this work was simply a synopsis of what China has endured for the past century. The nation’s legacy of scholarship, rich culture, and progressiveness has been soiled by horrible incidents of silencing those who speak out peacefully and scandal and corruption driven by vapid and dangerous incentive.

His commentary is not a work born out of hate for this cultural heritage, if anything, it’s his widely broadcasted cry for help on behalf of a country he was proud to belong to. He fears that indoctrination and denial will eventually erase what Chinese identity was to him, that future generations of the Chinese people will forget their value and history by blindly following a treacherous Big Brother government. Ai is creating off a slippery slope for many already have forgotten, and his life has been permanently put on the line. Yet he still creates out of defiance. On the surface level, his work is directly combating the machinations of the Chinese government, but Ai Weiwei’s work demonstrates a long running theme of fighting against apathy. His work seeks to evoke heated, primal reactions to coax an opinion. Against indifference, Ai’s work forces attention to be placed on it. From there, an actual dialogue can be created and awareness, whether the audience is consciously forming it or not, can be born. In Ai’s philosophy, having any opinion is better than having no opinion at all. It is indifference that destroys, and so when given the choice to live in peaceful ignorance or risk death to himself and his loved ones, Ai Weiwei does not hesitate to choose the latter every single time. In his own words, “Without freedom of speech there is no modern world, just a barbaric one.”

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#helloblarty#porcelain#ai weiwei#chineseart#china#han dynasty#colored vases#21st century art#modernism#modern art#jingdezhen#ceramics#weiwei#chinaware#asianart

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was incredibly lucky to be able to see Mona Hatoum’s Terra Infirma exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation a little over a year ago. All the work in the collection was incredibly diverse and highlighted Hatoum’s multitalented skillset from the intricate blown glass grenades to gargantuan mobile sculptures. In her distinctive hybrid of Minimalism and Surrealism, my curiosity was captured by the remarkable silhouettes and the brilliance in the saturation of her work. Though I was thoroughly awed by the whole of the exhibition, it was this piece, Homebound, that demanded my attention and firmly held it even as I stepped beyond the confines of the room housing the installation.

I walked in at the beginning of the installation’s cycle. Intensifying electric buzzing and a pounding tattoo of pulsing lights greeted me. The impression of a household is restricted within the space of a little over half of the room. Kitchen tables, bed frames, cradles, all furniture reminiscent of the 1960′s to 70′s made up the scene. The noise was there, as was the clutter, yet the life that would have filled that room was noticeably absent. It’s difficult to say in the least to pinpoint the exact emotions Homebound conjures within me. But that was Hatoum’s intention with Terra Infirma and the mission of much of her art: to capture the confusing, conflicting feelings that are evoked from the human experience. Life through her lens is embraced for all its nuance and contradiction. It isn’t so obviously divided between black and white, good and bad, sadness and contentment. Hatoum cites her own life as inspiration for this artistic philosophy. Born into a Palestinian family in Lebanon, Hatoum always felt like an outsider in her own life. Even within her own family, her pursuit of the visual arts was something she kept closeted. When she fled the country in 1975 after the outbreak of the civil war, she was liberated in many ways, even as a refugee. She was able to establish an artistic career, an unadulterated one at that. Hatoum focused and expressed concepts that were considered taboo at best and life threatening at worst before she immigrated to London.

She made work that spoke to the perpetual foreigner, to female sexuality, to how grand cultural forces such as politics and power affect individuals. It’s that vulnerability with which Hatoum touches her audience. I come from a vastly different background than the artist, and yet, her art made an intimate connection to me as an individual. Homebound is Hatoum’s commentary on how conflict ravages families. There’s more than just physical separations that can drive great divides within a family, and whether a viewer is coming from a place of stability and privilege or the third world, that's a theme everyone can relate to on some magnitude or another.

Hatoum is unique in that it is easy to see her as an artist and as a person at face value based on everything she has experienced and overcome. While that is undoubtedly a significant influence on her work, if you spend time with her art, she subverts those impressions. Her art is not esoterically specific to her life, if anything, it inspires deeper thinking and introspection of a viewer’s own answers to timeless, universal questions that have been pondered for ages. The emotional ambiguity of Hatoum’s art gives the viewer, any viewer, the power to take what they will out of it. That share of creative discretion, of opinion, between artist and audience never fails to excite me, and for me, Mona Hatoum is an exceptional architect of this inextricably intertwined power balance.

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#modern art#minimalism#surrealism#installation#installation art#terra infirma#mona hatoum#palestinian art#helloblarty#21st century art#modernism#pulitzer arts foundation

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s the dawn of the 1930’s. The Great Depression is roaring as the financial high of the 1920’s is bitterly silenced, the country has gone dry, and to top it off, you’re a gay black man in the American South. To anyone, this would be a nightmare; to Beauford Delaney, these were the trials and tribulations that defined his art; to his critics and contemporaries, these are the details that made the man; and to us, this is the background to the extraordinary life we should remember him by.

Delaney was a Knoxville native who was encouraged by his mother Della, an ex-slave, to pursue an education and be acknowledged as a member of society, ideas she lived her entire life thinking were impossible dreams. Beauford and his brother Joseph both had a natural inclination towards the visual arts, and Beauford in particular shone through his talents. In Joseph’s words, “One distinct difference in Beauford and myself was his multi-talents. Beauford could always strum on a ukulele and sing like mad and could mimic with the best.” Though he flourished in Knoxville’s art scene, Delaney felt his calling was beyond what Tennessee could provide and migrated to New York.

For Delaney, New York thrummed with life in a way that was exclusive to the city. He arrived as the Harlem Renaissance was blossoming and became a frontrunner of the movement. His art sought to capture what Harlem inspired in him: a wonderful conflict of feelings of being at the intimate core of a community and the thrill of anonymity in restless crowd. The Portrait of James Baldwin is just a taste of Delaney’s style. His impressionist influences are evident in the way he experiments with the vibrant palette of the work; pastel blues shade pale beiges, and the amorphous backdrop is thickly layered with stokes of everything between loud turquoises and muted pinks. While the way he indicates light within this piece speaks to his artistic roots, this portrait also tells of the pivotal transition Delaney’s paintings made in American art history.

His obsession with the intertwined relationship between light and color long preceded the Abstract Expressionism of the mid 20th century (see the Rothko post for more information). Delaney’s experimentation and innovation with branching off from his classically trained, Knoxvillian roots not only brought the refined spirit of Europe onto the United States’ canvas, but also created some of the main sources of inspiration for one of the few uniquely American art movements; grouped jazz and baseball, the AbEx movement is one of the few things that are of complete American pedigree.

In the former half of the 20th century, there was no culture in existence that could categorize Beauford Delaney, and those that exist today, whether they remember it or not, had his hand in the making. Even if you can’t appreciate his art, Beauford Delaney’s biography and legacy are something to be admired. From black sheep to shepherd of the flock, Delaney made a place for himself and countless other outliers from premises no one else wanted to tread.

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#beauford delaney#harlem renaissance#african american art#portrait#portraitofjamesbaldwin#black history#helloblarty#20th Century#20th century art#lgbt#lgbt art

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

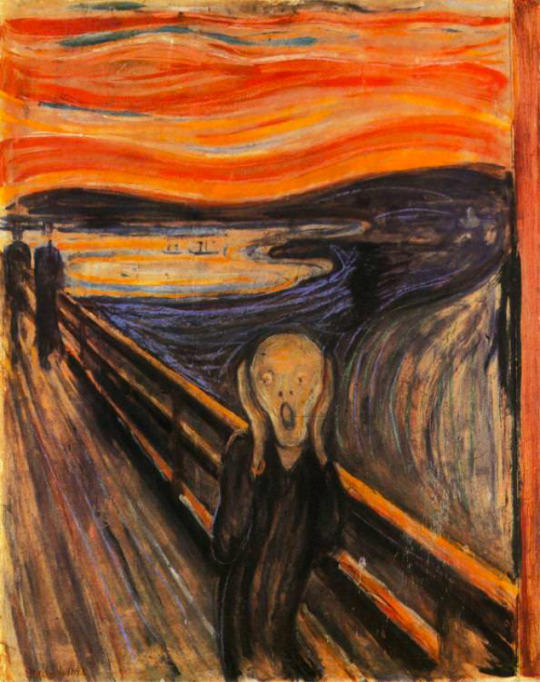

Along with the Mona Lisa and American Gothic, Edvard Munch’s The Scream has become one of the most ubiquitous pieces in all of art history. It has been parodied and referenced in TV shows and movies spanning from The Simpsons to Home Alone yet despite our virtually inherent familiarity with The Scream, we’ve forgotten so much about the meaning of its content and the man behind the canvas. The entire history of the painting’s eras of cultural progression and regression is incredibly extensive and nuanced, certainly an area of study I couldn’t do justice with a 500-something-word post (for a more in depth discussion of Munch and The Scream, I’d recommend reading So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch by Karl Ove Knausgaard). Suffice it to say, I’ll do my best to give an adequate introduction to Edvard Munch through a basic analysis of his most famous painting, a story that--for our purposes--we’ll start in 1893.

To start, Munch was a prominent artist of the school of Expressionism. Stylistically and dogmatically running along a similar vein to movements such as Neo-Impressionism and the Vienna Secession, Expressionism sought out to capture human experiences and emotions in a way that didn't conform to the traditional ideal of realism. This general philosophy is well exemplified in The Scream. In the foreground, the sexless, waif-like namesake of the work stands as the focal point of the piece. Any clue as to the identity of the figure is left intentionally ambiguous as they possess only the most elementary characteristics of a human being; they aren’t any person in particular, simply a representative of anyone and everyone. The backdrop surrounding the figure is hazy and distorted, though not calming. The fiery sky violently streaked with hues of warmth sinks to meet the cool and neutral world beneath it. Munch didn’t disguise his bold brushstrokes or the chaotic energy of the piece. The distressed character in the foreground seems to be the only one cognizant of their threatening environs as life seems to continue outside of their anxiety: two passerby stroll along the bridge and boats ferry across the horizon. Though cartoonish and obviously not a literal reflection of our world, The Scream is especially relatable in that it captures the essence of the almost claustrophobic helplessness of coming into solitary adulthood in a rapidly evolving social climate.

The Scream is Munch’s best known work, but the whole of his portfolio with such collections as his Frieze of Life, strengthens his claim as one of the most inventive and talented artists in conveying emotion. Ranging from bleak devastation to joyful celebration, Munch’s basis for his art was deeply nestled in his reality, a reality passable as a modern Greek tragedy. Munch’s childhood was shrouded in paralyzing fears of death, loss, and trauma. He lost several of his siblings and his mother at a very early age and was primarily reared by his paranoid, obsessively religious father. He spent his early life bedridden with thoughts of losing himself to mental illness and disease only to be met with an end of righteous punishment. In summary, Munch’s life was tragedy, an inescapable one at that. In his established career as an artist, Munch finally found an outlet in painting, one of the few joys he had growing up. Through his work, Munch expressed indescribable sensations of longing, contentment, feeling at home, and feeling like there was no place of belonging at all.

Though a significant portion of Munch’s work like The Scream evokes objectively negative feelings, in the same sense, there’s also a feeling of morbid comfort in looking at it. To know that, someone understands and sympathizes with how you feel even if that connection is built vicariously through their work. The Scream certainly isn’t a pretty painting, but it’s undeniably powerful. It confronts us with what we should already know about ourselves in a way that's scarcely been challenged. Though it approaches us through some inherent familiarity, The Scream and other Expressionist work have catalyzed novel discussions of how we relate ourselves to our psychology. In other words, the real legacy of Edvard Munch is his art’s propensity to inspire social change. With that, Munch will likely always be initially recognized as the painter of The Scream, but it would greatly serve us to also remember him as Edvard Munch, champion of the human experience.

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#19th Century#19th century art#munch#edvardmunch#modernism#modern art#expressionism#european art#helloblarty#blarty#the scream#scream

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

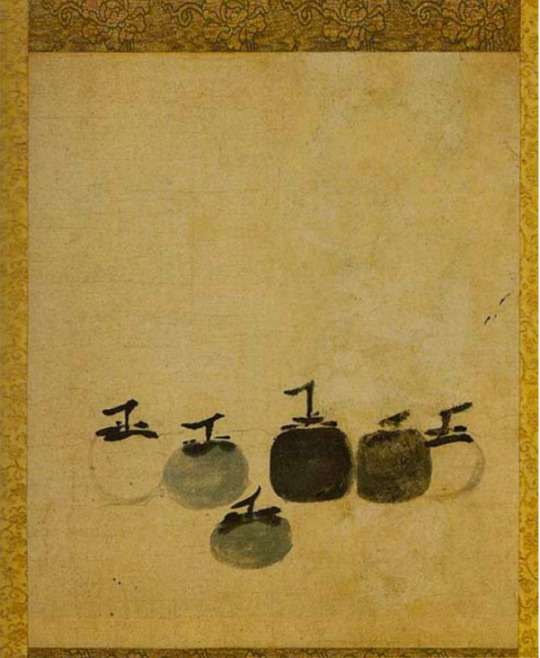

Six Persimmons was painted by 13th century Song Dynasty artist, Mu Qi. Simply, yet masterfully executed, the timeless ink wash has established a legacy of eliciting more questions than it answers. While its enigma may continue to stand in perpetuity, answering the ultimate question of what the piece means is one I often revisit. Every year or so as I take the time to reflect on its significance, my answers seem to paradoxically become less assured and my familiarity with the painting more questioned. Though in the beginning I was first troubled by this, I don’t see it as a point of insecurity anymore; rather, it prompts necessary of times of self reflection and motivation to expand my mindset and reevaluate where I’m at mentally and emotionally. While some might consider this to be somewhat of a non-answer, the Six Persimmons is both an emblem of how far I’ve come in personal maturation and self-esteem and a reminder of how far I’ve yet to go. My answer may change tomorrow or next year, but the spontaneity of my regards to Six Persimmons is what initially attracted me to the piece, and it’s what continues to strengthen my bond with it. So, in a question that has no true answer that has been entertained by historians, philosophers, Renaissance men, and—briefly—by this art history blog alike, when you see the Six Persimmons, what does it mean to you?

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#helloblarty#blarty#six persimmons#mu qi#Song Dynasty#13th century#chineseart#chinese watercolor#inkwash

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It would be quite a challenge to avoid Keith Haring’s work in modern American culture. His career, while tragically short, experienced a meteoric rise and revival that continues to this day. Haring’s iconic bold yet simplistic figures grace t-shirts and water bottles and lunchboxes and building façades and bevies of every imaginable opportunity for merchandising. Haring’s work has become a cultural staple for those growing up in Generation X onward. The popularity of Haring’s art could be considered a double-edged sword of sorts: in the one hand it has placed the artist in the spotlight and warranted discussion and praise surrounding Haring’s impact on modernism, and on the other the significance and messages in Haring’s images is either diluted at best and completely lost at worst to the general public. These themes in Haring’s work deserve to be restored as our society matures from and reflects on values held in the past that continue linger on today.

To start, Haring used his art as a platform to spread awareness of the realities of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and as advocation for civil rights for the LGBT+ community. Many pop artists such as the unofficial poster child for the movement Andy Warhol held a Dada like mentality towards art. Art was for art’s sake and was used primarily as a means for escape from the drama of political and societal realities with the occasional political statement made now and then. Haring differs in that he turned the international attention given to him directly towards bettering circumstances for the LGBT+ population.

This piece, Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death, showcases that mentality. Haring uses three of his famous stylized figures in a parody of the proverb of the three wise monkeys (see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil). Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death is a direct confrontation of the United States’ attitude to the AIDS outbreak. The HIV virus was unlike any other threatening virus the country had ever encountered. Unlike the flu or smallpox, the effects of HIV took years to surface, the mortality rate was essentially all who contracted it, and little was known about the mechanics or operation of the deadly virus. Despite the daunting threat posed by the disease, the AIDS issue was moralized as the majority of reported cases came from homosexual men in urban hubs such as San Francisco.

Much of the fear and mystery surrounding HIV/AIDS in the 1980s remained, and the course of action taken towards prevention by further relegating the queer community only served to exacerbate the crisis. Keith Haring was the champion the LGBT+ community never had before. He used his celebrity and simple motifs to turn the tide of polarization against homosexual individuals.

I think one of the main appeals to Haring’s chalk outlines is that simplicity. His work is an impression of life, stripped of its arbitrarily set boundaries and biases. In this form, many greater truths can be exposed such as that of the LGBT+ community. The truth that these people are neighbors, friends, community leaders, aunts, uncles, daughters, and sons, and above all else, people deserving of compassion.

In conclusion, Keith Haring’s legacy is so much more than the colorful figures dancing on notebook covers and socks. It’s one of eradicating indifference to difference, one of embracing diversity and accepting others, one we should all learn from and take pride in.

Happy Pride Month. 🏳️🌈

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#modern art#pride#pride month#keith haring#ignorance fear silence death#lgbtq#helloblarty#popart#aids crisis#1980s#haring

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ploughing at the Nivernais appears to be an unassuming image. Much like The Stonebreakers, the painting is a Realist piece in every sense of the word. From a technical standpoint the artist, Rosa Bonheur, devotes an almost photographic precision to the work through her delicate attention to details as minute as the sinew in each of the cattle’s bodies, the shadows cast by each blade of grass. The painting’s contents lie in the heart of Realism, that core which we have discussed previously with Courbet. Ploughing at the Nivernais is another vignette into the everyday lives of the third estate, of ordinary people, a novelty to the artistic community in the 19th century that was accustomed to catering to wherever wealth was concentrated. Realism captured a face of reality that had been lost in art; the movement focused on the genuine struggle and sacrifice and scrappy lives made in earnest that had been altogether ignored. While Ploughing at the Nivernais did break barriers as one of the most prominent and celebrated pieces in Realism, the painting is extraordinary for reasons beyond its creative merits.

Rosa Bonheur was an individual of incredible talents that toiled to establish her career and legacy even when challenged by two crippling fronts of adversity against her identity. Bonheur was an active painter in France in the mid-19th century. Even in a post Revolutionary society, even in a post Enlightenment society, the Western world was still largely patriarchal and governed by such archaic concepts as the Doctrine of Two Spheres and biological bases of supposed male superiority. Women were denied entry much less careers in virtually every industry and enterprise save for domestic responsibilities. Serious and cultivated mediums such as sculpture or oil painting were strictly reserved for men and women were often confined to little more than crafts such as needlepoint. Bonheur utilized her father’s connections (he was a landscape painter) to go through the traditional art curriculum and became a professional animalière, achieving if not superseding the level of skill displayed by her male contemporaries.

In addition to the discrimination Bonheur faced as a woman, she was also openly lesbian. Bonheur was renowned for her eccentric and confident personality. She refused to mold herself to the confining gender roles of the time as another one of many silent shirking violets. The thought of any romantic or sexual orientation other than heterosexual was mythic, cryptic at the time. The thought alone was unexplored and taboo, and aside from the outrage and fear surrounding it, LGBT culture in Europe was virtually nonexistent.

Despite these challenges, Rosa Bonheur flourished as an artist and is considered by many critics and historians to be one of the best known female artists in history and one of the keystone artists of Realism. Bonheur was unapologetically herself in every regard be it in her embrace of unorthodox femininity or her sexuality. She carried herself with a confidence that rivaled that held by many men of her era, and that admirable and healthy sense of self was well deserved. Bonheur’s career was truly her own as she faced discrimination and unending criticisms on her work due to completely unrelated prejudices. Though she herself would be unfamiliar to the term, Rosa Bonheur completely embodies the essence of pride; even in an environment where all the odds were grossly against her, Bonheur worked to prove that she could be successful without sacrificing any aspect of herself and set a precedent for female and queer artists to look up to.

Happy Pride Month. 🏳️🌈

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#pride#pride month#rosa bonheur#ploughing at the nivernais#19th century art#19th Century#lgbtq#helloblarty

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cindy Sherman’s Bacchus is a curious image, and it is one of a myriad from the influential photographer’s prolific career. I think what is captivating about Sherman’s work is its boldness to venture into the previously undefined. At photography’s conception the art form was coveted for its ability to capture reality at any given instant. Innovative artists such as Dalí gave a new layer of nuance to photography by introducing the element of fantasy to pictures. These early works from Daguerre’s first stills to Dalí’s Atomicus are integral in the history of photography as the former represents the ultimate human achievement of exactness we have been striving for for centuries, and the latter represents the height of impossibility we can reach with a camera and boundless creativity. Sherman’s work resides in a gray zone between these two types of photography. This metaphorical gradient of Sherman’s portfolio establishes its own brand of intrigue that has in turn contributed to her relevancy and august reputation as an artist.

To start, Sherman’s art is very much rooted in not only in fundamental reality but also in our culture. In the case of Bacchus, Sherman pulls inspiration from Caravaggio’s original painting. While many of her images reference iconic pieces from the classical period to the baroque, Sherman does not limit herself to academic art. Her many series encapsulate a broad and extensive range of diversity and complexity from alluding to biblical parables to capturing the essence of contemporary pop culture. Sherman’s career is the paradigm of artistic versatility and evolution, and her unique use of self-portraiture is key to understanding her creative legacy.

In placing herself at the heart of her photographs, Cindy Sherman cements a personalized bond between herself and her work. Spiritually, and in some senses literally, Sherman makes each scene a part of her identity. That humanizing aspect to her art draws in the attention and emotions of the viewer. Hearkening back to the cultural significance of Sherman’s parodies, photographs such as Bacchus are innately relatable. However familiar we may feel with the sight of these classic pieces, or however confident we feel with our knowledge of their histories, viewing them through Sherman’s lens adds an unpredictable shift to our perspective.

To end, Sherman’s work is compelling for a multitude of reasons, the majority of which derive from the idea of Sherman’s photography existing in that aforementioned gray zone. Her body of work challenges our traditional views of the media of photography and the traditional arts. It is this provocation that stirs a revival of fascination to the classical past and inspires further experimentation in photography and film. For several decades now, Cindy Sherman has perfected her methodology to bending our perceptions of reality to her desired mold of fantasy. Through this experience, we are encouraged to question and analyze the symbolism of her work and how those investigations apply to the lives we carry on past the gallery walls.

#art#arthistory#modernism#modern art#cindy sherman#cindysherman#bacchus#helloblarty#20th Century#20th century art

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photography is a medium that is not in my repertoire and one I don’t often study, but there is just an air to Brandon Woelfel’s work that feels so magical to me. Admittedly, his realm of work is not something I am even slightly familiar with; however, I just had to take the initiative this week to write about him. Artists working in traditional media face the challenges that come with creating new worlds from scratch, but I think the novelty with which Woelfel fascinates me stems from his gift to mold his own brand on reality directly from that with which nature endows us.

The photograph above is a pretty wholistic showcase of Woelfel’s general body of work. Based in New York, the photographer begins with the chaos and occasional grime of the urban streets and shapes that basis into a muted cotton candy fantasy world. Harsh and flashy lights become a gentle pastel ambiance, the rest of the world around the model seems to evaporate, and time is suspended in a state of permanence. It is so easy to be awestruck by the catharsis evoked by sculpture or painting and find yourself disenchanted by the disconnect between that view and our comparatively mundane and sparse surroundings. Woelfel’s photography strikes a genuine sense of optimism within me. Whenever I look at his work, I become inspired to find the beauty in my own life, a raw charm in my environment that can be coaxed out with a deeper glance.

Some critics of Woelfel claim his portfolio lacks diversity and is evanescent in its mass appeal. I cannot predict how the majority opinion on Woelfel may sway in the future. Perhaps it will be true that Woelfel’s contemporary popularity will prove to be more a product of clout than longevity; but personally, he is an artist whose pieces will continue to resonate with me. I also believe Woelfel is an artist who possesses a depth and breadth that is akin to any of the artists I’ve previously discussed. His cityscapes are shot in places that are objectively unattractive; harkening back to the Ashcan movement, the concrete jungle has acquired a reputation for its harshness and seediness. He takes up the gauntlet to work with these often overlooked areas and captures a moment and stretches it out for forever. This indefinite existence that is so grounded to reality, to recognizable and tangible things in our lives, reminds me of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss. Brandon Woelfel’s ability to shift from a place of moral ugliness as depicted by the Ashcan School to the transcendence and warmth of the hallmark of the Vienna Secession speaks for the value of his work. The consistency and attention with which he shoots and edits his pieces sets him apart from those who jump on the bandwagons of gimmicky photography and pseudo-intellectual/hipster culture. On the whole, I just find Brandon Woelfel incredible, and his work certainly places his a career on a level of artistry that warrants the immense success the young photographer has enjoyed so far.

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#arthistory#modern art#photography#brandon woelfel#pastel#21st century art#helloblarty#woelfel#luminescence#fluoresence#light#brandonwoelfel

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are you a tory?

No, I am not. I am unaffiliated with any British politics.

3 notes

·

View notes