Photo

From: theanarchistlibrary.org

Kaneko Fumiko (1903-1926) was a Japanese anarchist living at the early part of the 20th century. Born out of wedlock into grinding poverty, she lived her life as an outsider within Japanese society including a stint with unloving and cruel relatives in then-occupied Korea, her experiences inspiring both her rebellion against authority and feelings of solidarity with others on the receiving end of society’s boot. Together with her friend, partner and, before her death, husband Pak Yol, she started underground anarchist societies, published articles against the Japanese state and society, and, perhaps, planned to kill the Emperor Taisho and then-Crown Prince Hirohito with explosives at Hirohito’s wedding.

She and Pak were some of of many who’d be swept up in the mass arrests and killings of enemies of the state both real and perceived after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Placed into “protective custody,” she and Pak were tried and sentenced to death for high treason on charges related to a plot to kill the Emperor and Crown Prince. While these sentences was later commuted to life in prison by the Emperor, an honor she promptly rejected by tearing the decree up in front of her jailers, she was found hanging in her cell in 1926 and is supposed to have committed suicide.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From Enough 14.

Social rebel, counterfeiter, bandit, modern Robin Hood – the list of titles with which our anarchist comrade Lucio Urtubia was honoured is long. His life, which sounds like an adventure novel, is a mirror of the revolutionary movements in Europe in the second half of the 20th century. Lucio Urtuba passed away today (18 July, 2020). Rest In Power Lucio!

Lucio Urtubia was born in 1931 in a small village in Navarre and grew up in poor conditions. When he was called up for military service, he deserted to France shortly afterwards, where he worked as a bricklayer from then on. He came into contact with anarchist groups and met his political foster father: the legendary Sabaté, who organized the armed resistance against the Franco dictatorship from France. Forging documents, hiding underground fighters and illegal fundraising activities play a major role in his life from then on. Numerous resistance organisations, which have a base of operations in France or are looking for a place to retreat, benefit from his skills: Black Panthers, Tupamaros, European guerrillas. Lucio’s solidarity is with every act of revolt aimed at a more just social order.

In 1962, he proposed to Che Guevara, then head of the National Bank of Cuba, to flood the world market with counterfeit dollar bills in order to destabilize the US economy. The proposal meets little approval on the Cuban side, but the idea remains alive in Lucio. In 1980 he succeeds in his greatest coup: by printing traveller’s cheques from Citibank with a value of several million dollars he brings the then most powerful bank in the world on its knees.

But the list of his activities is not completed. Lucio is also a master of conspiracy, however, who manages to spend only a few months in prison in his not exactly law-abiding life. He breaks the silence at the age of well over 70. There is a book and also a movie (Watch here) about Lucio Urtubia.

Lucio, The Good Bandit: Reflections of an Anarchist

Marie Trigona, Toward Freedom (05/06/2008)

Outspoken and charismatic, Lucio speaks like a true anarchist. When asked what it means to be an anarchist, Lucio refutes the misperception of the terrorist, “The anarchist is a person who is good at heart, responsible.” Yet he makes no apologies for the need to destroy the current social order, “it’s good to destroy certain things, because you build things to replace them.”

Lucio has old friends in the Southern Cone. Funds from the forgery operatives helped hundreds from revolutionary organizations exile and finance clandestine actions against the bloody dictatorships which disappeared ten thousands of activists, students and workers during the 1970’s throughout Latin America. In Uruguay, funds from falsified Citibank travelers’ checks funded the guerilla group Tupamaros, in the US the Black Panthers and other revolutionary groups throughout Europe.

During his recent visit to South America, Lucio stayed at the worker run BAUEN Hotel in Argentina’s capital Buenos Aires. He was astounded by the accomplishments of the workers without bosses. At the BAUEN hotel, workers are putting into practice workers autogestíon or self-management. Self-management has been a mainstay of anarchist thought since the birth of capitalism. Rather than authority – obey relationship between capitalists and workers, self-management implies that workers put into practice an egalitarian system in which people collectively decide, produce and control their own destinies for the benefit of the community. But for such a system to work, participants have to be hard working and responsible, one of the most important attributes a man or woman should have according to Lucio. “The anarchist movement was built by workers. Without work we can’t talk about self-management, to put self-management into practice we need to know how to do things, to work. It’s easy to be bohemian.”

Lucio explains that his anarchism is based in his poor childhood in fascist Spain. “My anarchist origins are rooted in my experience growing up in a poor family. My father was leftist, had gone to jail because he wanted the automony of the Basque country. For me that’s not revolution, I’m not nationalist. With nationalism humanity has committed a lot of mistakes. When my father got out of jail he became a socialist. We suffered a lot. I went to look for bread and the baker wouldn’t give it to me, because we didn’t have money. For me poverty enriched me, I didn’t have to make any effort to lose respect for the establishment, the Church, private property and the State.”

In Spain, fascism persevered 30 years after the end of World War II. Hundreds were placed in jail for resisting the Franco dictatorship. Anthropologists have estimated that from the onset of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936 to Franco’s death in November 1975, Franco’s Nationalists killed between 75,000 and 150,000 supporters of the Republic.

Lucio exiled to France where he discovered anarchism. He had deserted the nationalist army and escaped to France. Paris in the 1960’s was a bourgeoning city for anarchist intellectuals, organizers and guerillas in exile. It was there that Lucio met members from the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, Confederación Nacional de Trabajo (CNT). He was anxious to participate.

During his early years in France, Lucio met Francisco Sabate, the legendary anarchist and guerilla extraordinaire. At this time Sabate, otherwise known by his nickname “El Quico” was the most sought after anarchist by the Franco regime. French police were also looking for Sabate, who led resistance against Franquismo. “When I met Quico, I was participating in the Juventud Libertarias. They asked me if I could help Sabate, me an ignorant, I didn’t know who he was.” Sabate used Lucio’s house as a hide out. The young Lucio, listened to Sabate’s tales of direct action and absorbed whatever wisdom he had to offer, like methods for sniffing out infiltrators. “I met guerillas that put me on the road to direct action and expropriations. Sabate taught me to lose respect for private property.”

It was then that Lucio began participating in bank robberies. “There are no bigger crooks than the banks,” says Lucio in the defense of expropriation. “[This was the] only means the anarchist had, without funding from industry or government representatives to fund them. The money was sent to those suffering from Franco’s regime.” Student organizations and worker organizations received the funds to carry out grass roots organizing. In other cases the money was used for the guerilla actions against Franco’s regime, such as campaigns for the release of political prisoners in the nationalist jails.

To save the lives of exiles, Lucio thought of a master plan to falsify passports so Spanish nationals could travel. “Passports for a refugee means being able to escape the country and lead safe lives elsewhere,” he explains. Not only in Europe but in the US and South America, dissidents used false ID’s to lead their lives and direct actions.

In 1977, Lucio’s group began forging checks as a direct form to finance resistance. Lucio was essentially the “boss” of the operation-he made, distributed and cashed the checks. The checks were harder to falsify than counterfeit bills. Lucio thought they should target the largest banking institution in the world, National City Bank. The distribution of the checks went to different subversive groups who used the funds to finance solidarity actions. Lucio explains that “no one got rich” from the checks. Most of the funds went to the cause. All over Europe, these checks with the same code number were cashed at the same time.

Lucio’s master plan cost City Bank tens of millions of dollars in forged travelers’ checks. But many say a much larger sum was expropriated. City Bank was at the mercy of the forger, who had cost so much that the bank had to suspend travelers checks, ruining the holiday for thousands of tourists. At the time, people did not use check cards or credit cards. Lucio was arrested in 1980 and found with a suitcase full of the forged checks. In the meantime during Lucio’s arrest, Citibank continued to receive false travelers’ checks.

Citbank became worried. Representatives from the bank agreed to negotiate. Lucio would be released if he handed over the printing plates for the forged checks. The exchange was made, and Lucio became a legend for his mastermind plan. Although his life as a forger ended at 50-years-of-age, his life as an anarchist continued.

Lucio had always worked as a bricklayer. “What’s helped me the most is my work, Anarchists were always workers.” Lucio-bricklayer, anarchist, forger and expropriator has left a legacy like his predecessors. “People like Loise Michel, Sabate, Durruti, all the expropriators taught me how to expropriate, but not for personal gain, but how to use those riches for change.” At 76-years-of-age he does not apologize for his actions. “I’ve expropriated, which according to the Christian religion is a sin. For me expropriations are necessary. As the revolutionaries say, robbing and expropriation is a revolutionary act as long as one doesn’t benefit from it.”

51 notes

·

View notes

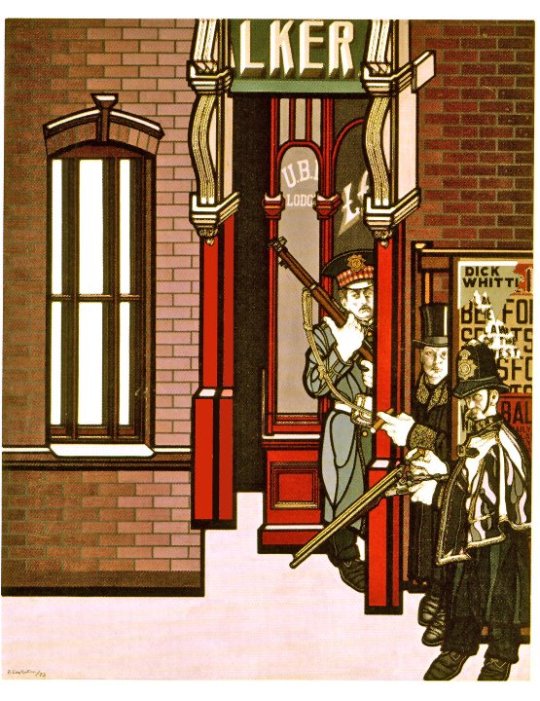

Photo

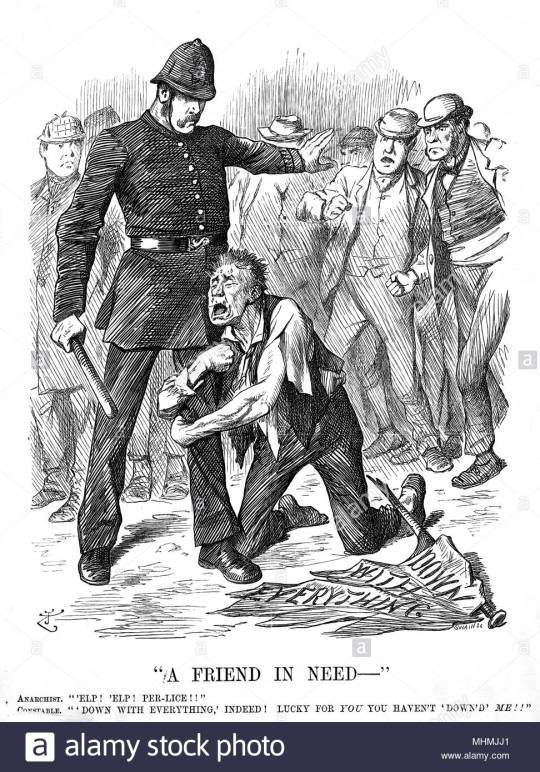

An anti-anarchist political cartoon printed 1894. Note fallen banner proclaiming “Down With Everything” and the policeman’s quip “lucky for you you haven’t down’d me!!”, while ostensibly protecting the anarchist from a gathering mob.

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine. [I] recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide.

Victor Serge, once proximal to the French illegalists (including the Bonnot Gang) describing his younger years in a posthumous memoir, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951).

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

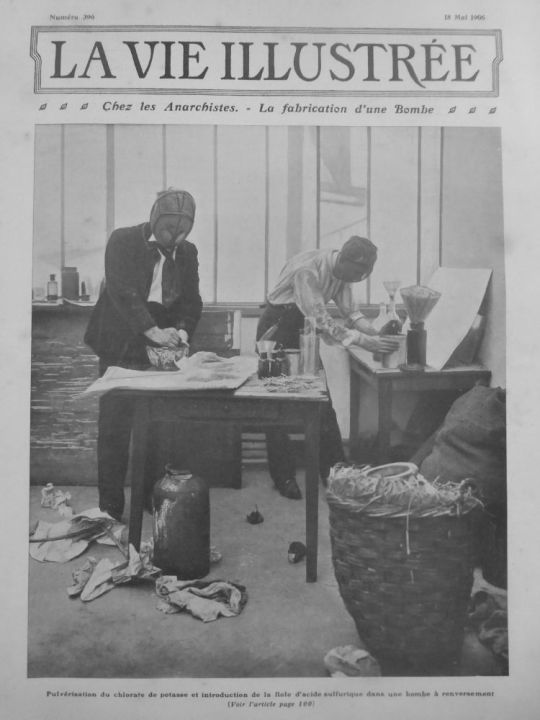

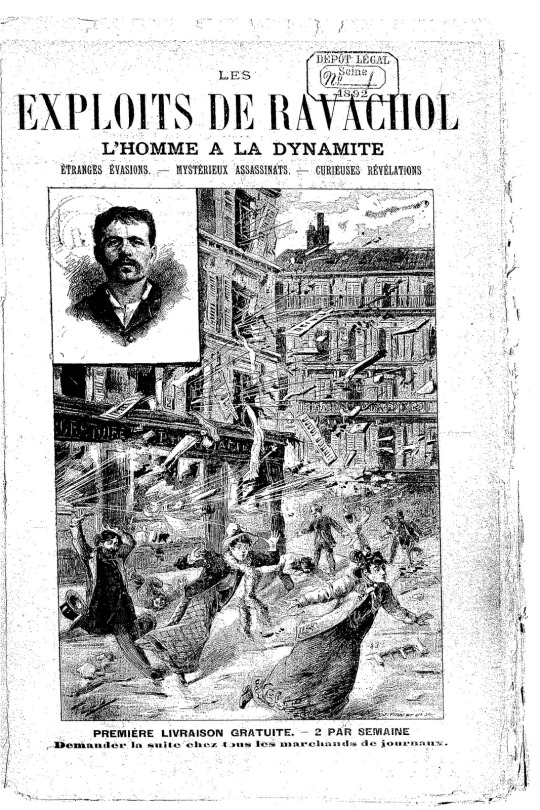

Among the Anarchists / The Making of a Bomb (1906)

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

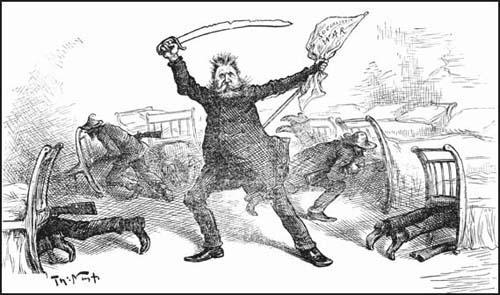

A cartoon of Johann Most from Harper’s Weekly, May 1886.

Most was a famous early advocate for propaganda by the deed, having once declared “the existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion.” His advocacy for revolutionary violence peaked with his publishing of “The Science of Revolutionary Warfare” (1885), a bomb-making manual.

Johann Most later influenced and subsequently befriended a young Emma Goldman. While for a time she felt “infinite tenderness for the great man-child”, Goldman and Most had a very public falling out after Most criticized Alexander Berkman’s assassination attempt of industrialist Henry Frick. Goldman famously confronted Most at a lecture and beat him with a horsewhip. She later expressed regret for having done so, explaining that "at the age of twenty-three, one does not reason".

#johann most#propaganda by the deed#attentat#chicago anarchists#Emma Goldman#alexander berkman#anarchy#Anarchist#anarchist history

57 notes

·

View notes

Quote

If ideas alone could save the world, I challenge anyone to invent a new one. The time for ideas is over. It is time now for deeds and action.

Mikhail Bakunin, 1873

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photos of IEDs found at Louis Lingg’s apartment following the Haymarket massacre. Having been arrested and charged with throwing explosives at police officers, Lingg proclaimed his innocence, explaining that he had an alibi - he was busy at home making bombs at the time.

#louis lingg#Haymarket#Haymarket massare#haymarket martyrs#Haymarket Affair#Anarchist#anarchy#anarchism#hang me for it#chicago anarchists

277 notes

·

View notes

Photo

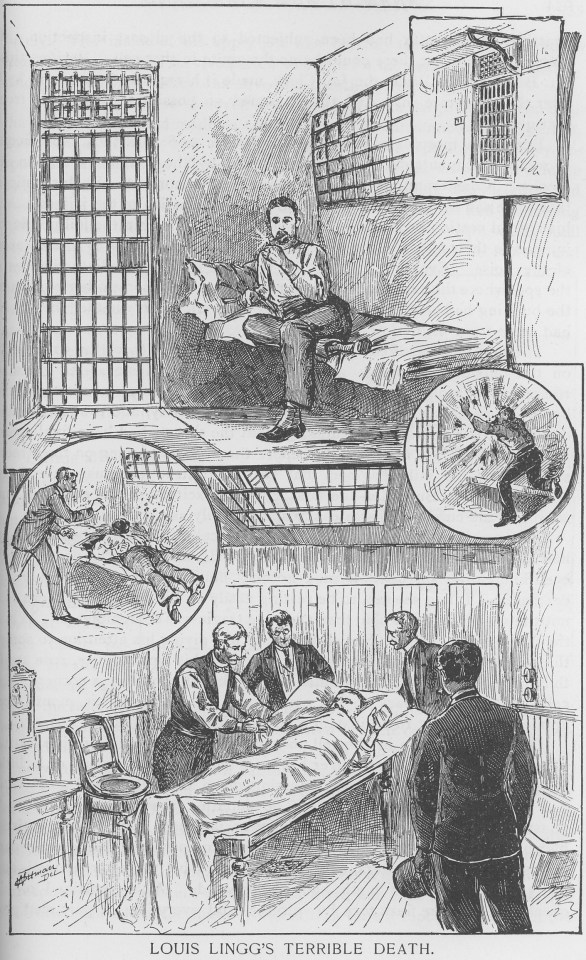

Accused of throwing explosives during the Haymarket Affair, unapologetic anarchist Louis Lingg was imprisoned May 14th, 1886. On November 10th, 1887 - the day before he was scheduled to be hung - Lingg placed a blasting cap between his teeth and lit it like a cigar, choosing to die on his own terms rather than let his fate be determined by the state. The resulting blast gruesomely tore apart his lower jaw, but did not kill him immediately. Lingg survived six more hours and in that time, he used his own blood to scrawl "Hoch die anarchie!" (Hurrah for anarchy!) in his native German upon the walls of his cell.

#louis lingg#Haymarket#Haymarket Affair#haymarket martyrs#mayday#propaganda by the deed#chicago history#anarchist history#anarchy#anarchists#anarchism

115 notes

·

View notes

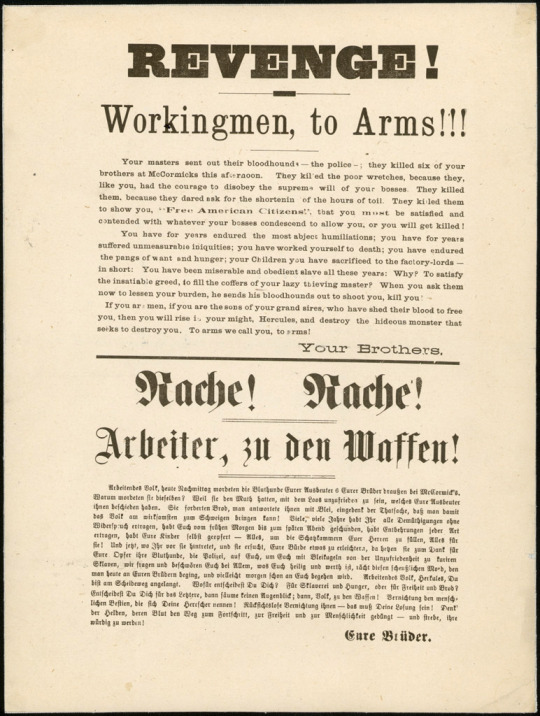

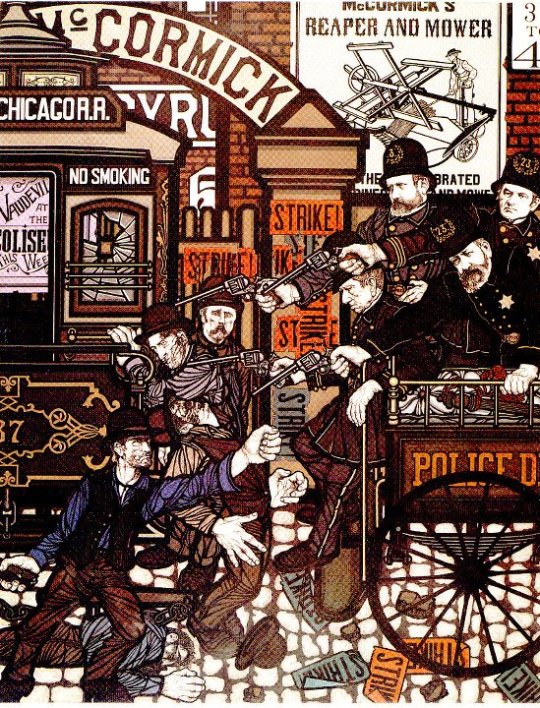

Photo

The broadside that Spies composed in the Arbeiter-Zeitung office after witnessing the riot at McCormick's expresses all his fury and frustration. "I was very indignant," he told the jury at the Haymarket trial. "I was excited. I knew positively by the experiences that I have had in the past that this butchery of the people out there was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement in this city."

The prosecution offered the broadside as a prime piece of evidence that the Haymarket bombing the next day was an intentional act of retribution in which Spies played a major part. Spies maintained that he did not write the inflammatory word "Revenge" (or Rache, in German), but that it was added by someone else. At the trial, Arbeiter-Zeitung compositor Herman Podeva (the spelling is different in other sources), who testified for the prosecution, explained under cross-examination that he was the one who inserted the word, mainly to give the heading "a better appearance."

The state also accused Spies of purposely exaggerating the number of workers killed. Spies claimed that he first reported two casualties, and that he then changed the number to six because at this point he honestly believed from his reading of the Daily News that six was the accurate figure. About twenty-five hundred of these circulars were printed, and a little more than half were actually distributed.

As in the case of Flinn's description of Officer Casey's rescue (see the previous entry), and of so much other writing produced at the time about Haymarket, of more importance here than the particulars is the language that Spies deployed. His rhetoric reveals how dangerously charged the moment was. Spies makes a direct appeal to the manhood of workers.

Manhood was an exceptionally sensitive issue because many laborers felt they had lost control of their lives to a capitalist system that devalued the skills that were so essential to their identity as well as their livelihood. Spies characterizes what happened at McCormick's as the capitalist "masters" loosing their bloodhounds—a frequently used derogatory epithet for the police—on workers simply because they stood up for their rights as free Americans.

The broadside declares that the time has come to end the worker's humiliation, exploitation, and hunger, his sacrificing of his children to the "factory-lords," and his "slavery." If you are men, Spies tells laborers, you will prove it by rising to "destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you." Spies concludes, as did so many anarchist articles and speeches and manifestos, with a call to arms. The identification of "the people" with the heroic figure of "Hercules" in the last paragraph dates back at least to the French Revolution.

The German version is, if anything, more vivid and inflammatory. A fairly literal translation:

“Working people, this afternoon the bloodhounds of your exploiters murdered six of your brothers at McCormick's. Why did they murder them? Because they had the courage to be dissatisfied with the lot your exploiters assigned to them. They demanded bread, and were answered with lead, because this is the best way to silence the people. Many, many years you have suffered all humiliations without resistance, have toiled from early morning to late evening, have suffered all kinds of wants, have even sacrificed your own children—all in order to fill the treasure houses of your masters, all for them. And now, when you appear before them and request some relief from your burden, they thank you for your sacrifices by setting their bloodhounds, the police, on you, to cure you of your dissatisfaction with leaden bullets. Slaves, we ask and conjure you by everything that is sacred to you, avenge this hideous murder, committed against your brothers today and perhaps tomorrow against you. Working people, Hercules, you have arrived at the crossroads. What are you going to choose? Slavery and hunger or freedom and bread? If you choose the latter, do not wait a moment: to arms, people, to arms! Destruction to the human beasts that call themselves your masters! Ruthless destruction to them, that has to be your password. Think of the heroes whose blood has fertilized the path to progress, freedom, and humanity, and strive to be worthy of them.

Your Brothers”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sacco and Vanzetti both stood their second trial in Dedham, Massachusetts for the South Braintree robbery and murders, with Judge Webster Thayer again presiding; he had asked to be assigned the trial. Anticipating a possible bomb attack, authorities had the Dedham courtroom outfitted with cast-iron shutters, painted to appear wooden, and heavy, sliding steel doors. Each day during the trial, the courthouse was placed under heavy police security, and Sacco and Vanzetti were escorted in and out of the courtroom by armed guards.

91 notes

·

View notes

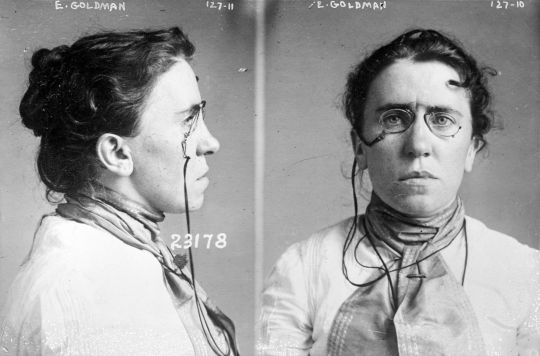

Photo

Mugshot of anarchist Emma Goldman from when she was implicated in the assassination of President McKinley, 1901.

391 notes

·

View notes

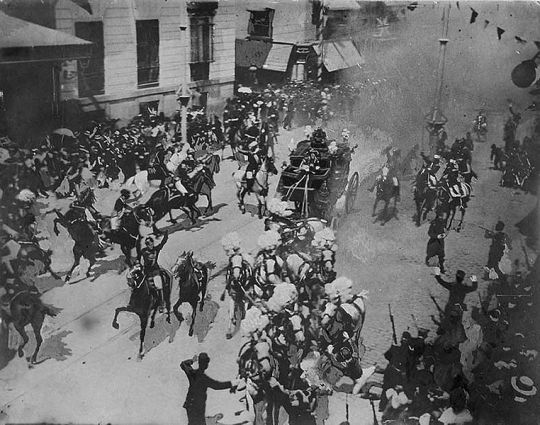

Photo

1906: An Anarchist’s bomb explodes amidst Spanish King Alfonso XIII’s retinue. Several bystanders and horses are killed, the King is unharmed, and the Queen gets some spots of blood on her dress.

255 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Members of Chernoe Znamia (Чёрное знамя or Black Banner in English), a Russian anarchist group formed in the early 1900s around the time of the First Russian Revolution. An Anarchist-Communist organization, that is, one which espoused Kropotkin’s goal of a free communal society in which each person would be rewarded according to his needs, however its immediate tactics of conspiracy and violence, were inspired by Bakunin.

Chernoe Znamia attracted its greatest following in the frontier provinces of the west and south. Students, artisans, and factory workers predominated, but there were also a few peasants from villages located near the larger towns, as well as a sprinkling of unemployed laborers, vagabonds, professional thieves, and self-styled Nietzschean supermen. Although many of the members were of Polish, Ukrainian, and Great Russian nationality, Jewish recruits were in the majority. A striking feature of the Chernoe Znamia organization was the extreme youth of its adherents, nineteen or twenty being the typical age. Some of the most active Chernoznamentsy were only fifteen or sixteen.

Nearly all the anarchists in Bialystok were members of Chernoe Znamia. The history of these youths was marked by reckless fanaticism and uninterrupted violence. Theirs was the first anarchist group to inaugurate a deliberate policy of terror against the established order. Gathering in their circles of ten or twelve members, they plotted vengeance upon ruler and boss. Their “Anarkhiia” (Anarchy) printing press poured forth a veritable torrent of inflammatory proclamations and manifestoes expressing a violent hatred of existing society and calling for its immediate destruction.” They were responsible for a number of bombings and assassinations during the Revolution and so dedicated to their beliefs that whenever one of them thought they were about to get arrested they would commit suicide instead. Those that were caught would usually deliver a rousing speech on Justice and Anarchy before they were executed, in the manner of Ravachol and Emile Henry.

716 notes

·

View notes

Photo

58 notes

·

View notes

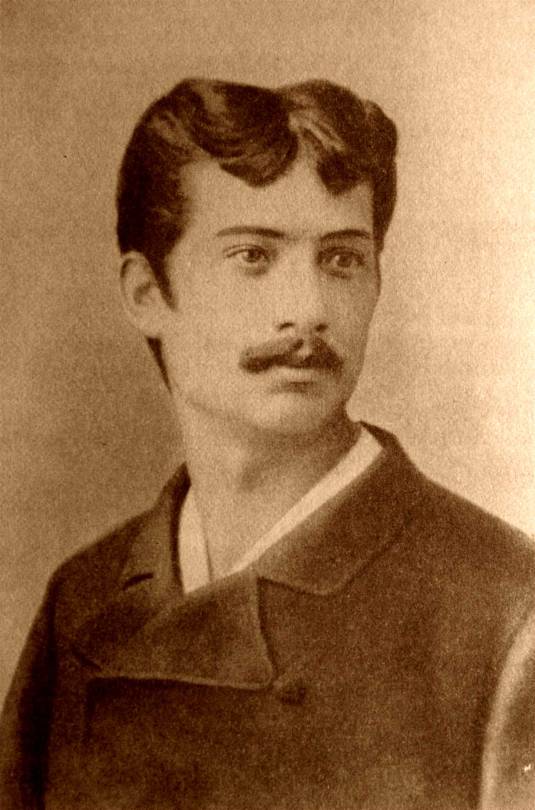

Photo

A young Luigi Galleani.

70 notes

·

View notes

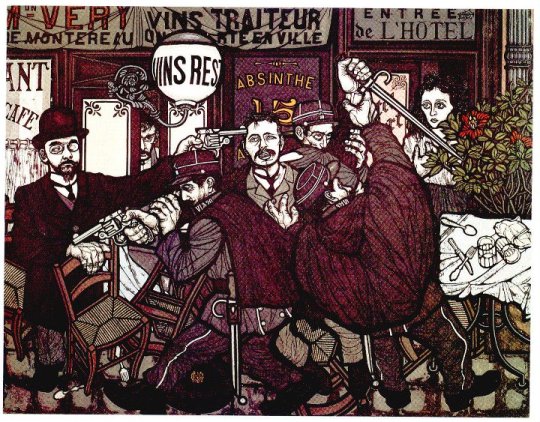

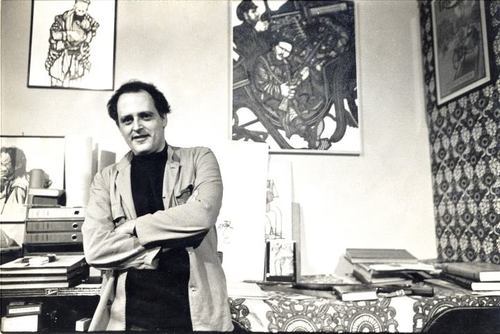

Photo

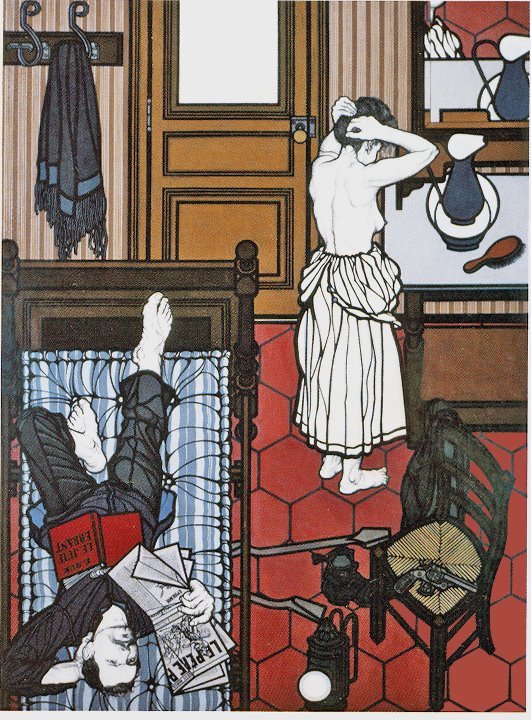

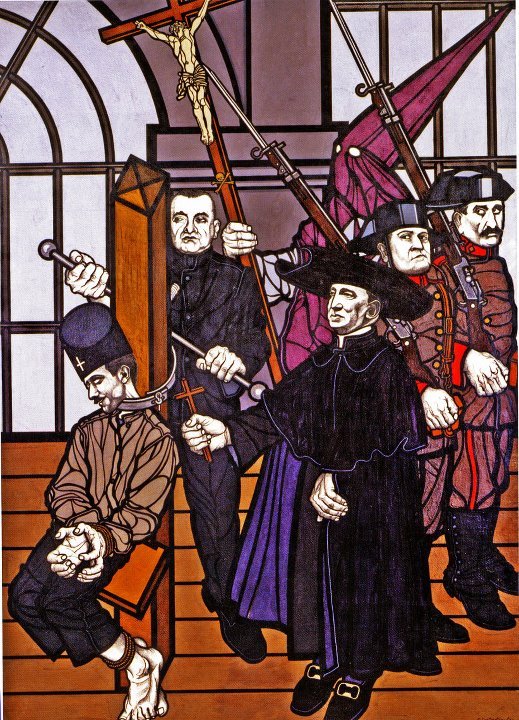

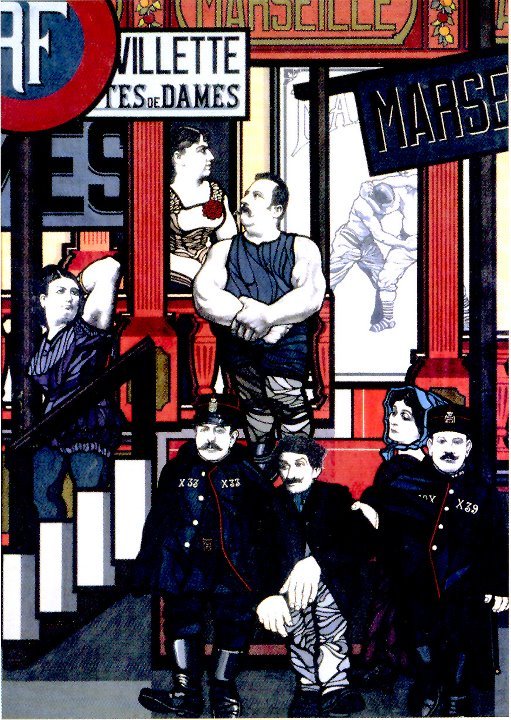

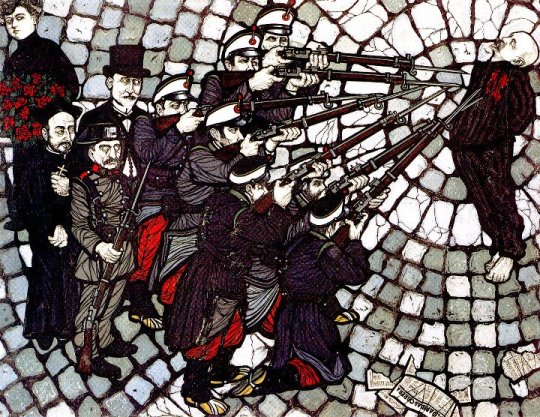

Flavio Costantini (1926 – 2013) ‘The Art of Anarchy’

Flavio Costantini was born in Rome, Italy, in 1926. He served in the Italian Navy before becoming a commercial graphic artist in 1955. He has illustrated several books including The Art of Anarchy (1974), The Shadow Line (1989) and Letters from the Underworld (1997).

More often than not it is the artist, writer or poet, rather than the historian or sociologist, who succeed in capturing the spirit of an age; in so doing, they make an important contribution to our understanding of society. Flavio Costantini is such a person. He sadly passed away on 20th May 2013.

2K notes

·

View notes