Text

Riddle Me This: The Tomb of Horrors

Before we go into how I plan out my traps, I’d like to take a look at how the pros do it. That is to say, I’d like to look at the traps and riddles included in official WotC books.

To start us off, I’ll be talking about the updated version of The Tomb of Horrors that’s included in the Tales From The Yawning Portal supplement book. For those who don’t know, the Tomb of Horrors is widely regarded as one of the deadliest, most unfair dungeons in the history of the game. It was originally created by Gary Gygax, the creator of D&D himself, in order to punish the players in his home game. The goal of the dungeon is to find the resting place of the demi-lich Acererak, defeat him, and steal his treasure.

This is a lot easier said than done, however. This dungeon has very little combat in it. The majority of the danger comes from the multitude of traps that wait for the unwary. As a bit of leniency, though, Acererak offers the adventurers some help near the beginning of the dungeon with a riddle warning them of the dangers of the tomb. The riddle reads as follows:

Acererak congratulates you on your powers of observation, so make of this whatever you wish, for you will be mine in the end no matter what!

Go back to the tormentor or through the arch, and the second great hall you’ll discover.

Shun green if you can, but night’s good color is for those of great valor.

If shades of red stand for blood, the wise will not need sacrifice aught but a loop of magical metal—you’re well along your march.

Two pits along the way will be found to lead to a fortuitous fall, so check the wall.

These keys and those are most important of all, and beware of trembling hands and what will maul.

If you find the false you find the true, and into the columned hall you’ll come, and there the throne that’s key and keyed.

The iron men of visage grim do more than meets the viewer’s eye.

You’ve left and left and found my tomb, and now your souls will die.

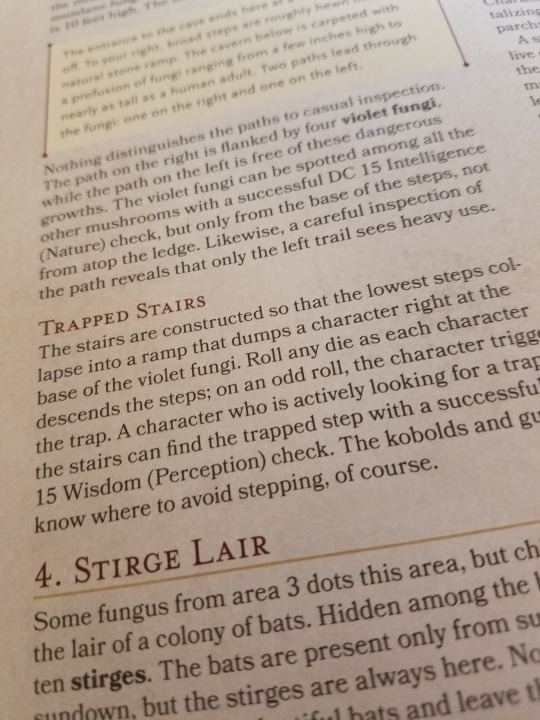

This riddle, should the party find it, holds clues to making it past some of the most insidious traps in the tomb, from doors hidden within spiked pit traps, to a pair of mosaics that teleport anyone who comes too close to different locations (the green one destroys anything that tries to go through it the other way). In the next part, we’ll look at what exactly the different parts of the riddle mean, and how misinterpreting them can lead to dire consequences.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Riddle Me This: A look at puzzles and traps

Dungeons and Dragons, on the whole, has significantly more of the former than the latter. Dungeons can be molded for any difficulty level and are easy to scatter throughout the world without making a big deal out of it. Dragons are almost all very difficult to fight, and are, inherently, kind of a big deal. So, it makes sense that most games use more Dungeons than Dragons.

Part of what makes dungeons so variable is the combat—a tomb full of zombies is going to be easier to get through than a demon fortress—but the real challenges in good dungeons are the puzzles and traps. Sure, combat comes with explicit rules for difficulty settings, so it’s easier to quantify, but a dungeon’s bread and butter is its headscratchers.

I can’t speak for anyone but myself here, but I always found deadly traps and mind-boggling riddles to be more fun in a dungeon than just about any fight. They’re a lot more satisfying, too. When you complete a difficult fight, you feel relieved that you won, and that you survived. But when you finally crack the code to open the door to the treasure room, there’s a sense of accomplishment. That wasn’t the dice, that wasn’t random luck, that was you with just your wits and the situation given to you by the DM, working within the limitations of your character’s understanding, to reach a solution and earn your reward. It’s addictive, and I love it.

How does that work on the DM’s side, though? How does a Dungeon Master go about designing these satisfying riddles and puzzles? How do they decide what the penalty is for getting the answer wrong? I’ll be exploring these questions a little bit in this upcoming series of posts, which I will be titling “Riddle Me This.” Hopefully I’ll be able to provide some insight into, at the very least, the methods I use to design my dungeons.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Better Big Baddies (Pt. 2)

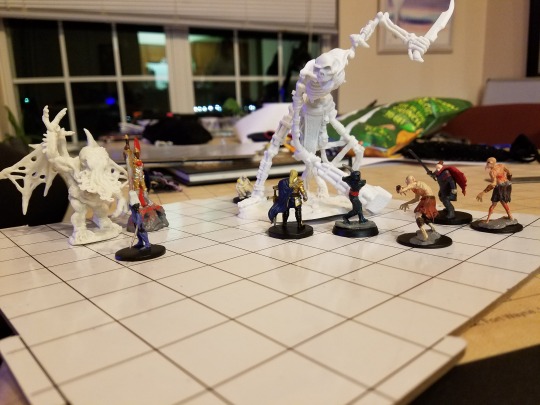

So, big enemies. Very cool in concept—how awesome is it to see a giant burst through a wall in a shower of rubble and dust, then turn and glare at the PCs, who immediately have to roll initiative? —but when it comes to the execution of these huge monsters, it’s easy for them to get overwhelmed by the players’ comparable individual damage and superior numbers.

To fix this, we have to get creative with combat. An easy fix is to add more enemies. If the party is being harried by other, less powerful creatures in addition to the massive creature, it divides their attention and allows your giant skeleton (using the same example from Part 1) to lay out some damage and be a proper threat.

But what if you don’t want to put other enemies in? What if you want the monster to be intimidating and dangerous on its own?

In my experience, there are two reasons why big enemies can end up as not particularly threatening, aside from the balancing act between damage and health that I discussed in Part 1. Number one is that there isn’t anything actually stopping the party from gathering around it and beating it up, and number two is that the DM plays the monster too carefully or simply.

For the first one, let’s imagine the skeleton again. It’s just got bony legs. What’s to prevent the party from just hacking away at its femurs until it falls over? Now imagine that the skeleton, say, blights the very ground it walks upon, dealing necrotic damage to everyone in a certain distance of it every round or so. Suddenly, the situation has changed. The super tanky barbarian will still probably charge in, but the squishy rogue is suddenly having second thoughts about being so close. It’s not much on paper, but in execution, the whole dynamic of the fight shifts.

For the second, we’re going to step away from mechanics and focus on the DM. It’s very easy to get stuck in the “attack loop” as I like to call it. That is to say, a monster gets attacked by a player, gets angry and attacks the player back, and then the player hits again on his next turn, and so on. If a monster is just standing there letting itself get hit, of course it’s going to be easy to hit. Rather than “wasting” a turn to move away, or having the monster take damage from opportunity attacks, a lot of DMs think that it’s more of a challenge if the monster keeps dealing damage. In reality, this just leads to a boring fight with a lot of the same thing happening over and over again.

Mix it up! Maybe your skeleton can kick out at the players and knock them away so it can change positions freely. Maybe your giant can grab a player in the middle of the fight, either as a hostage or to deal extra damage to them. Maybe your huge centipede can climb up the walls and attack from the ceiling. There are plenty of options to make big monster battles fun and engaging, you just have to put in a little bit more effort.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Better Big Baddies (Pt. 1)

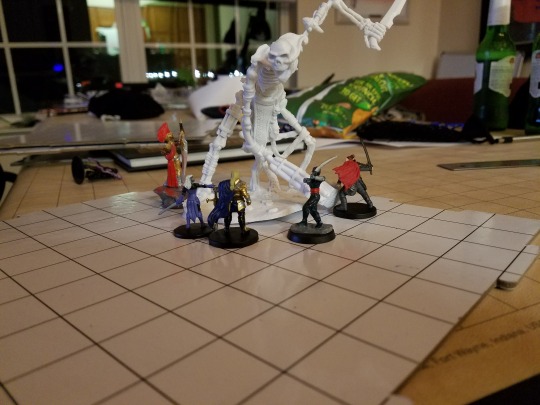

Everyone loves fighting monsters. “Roll dice, kill things” is the name of the game, whether you’re fighting a swarm of goblins or a twenty-foot tall skeleton, and it is exhilarating. And yet, the goblin swarm can very often be both more dangerous and more exciting for the players. Why is that?

Well, for starters, there’s a lot of strength in numbers. If 20 enemies are attacking you with one attack each, even though the damage is small, it adds up. The damage can also be spread among multiple targets, rather than just one. If a big enough swarm of goblins piles on the party, it could very easily end in a death. Conversely, the giant skeleton may be able to do a lot more damage with each attack, but it can only make one or two attacks per round, and only against one or two targets. Because of this, if the skeleton is the only thing that the party has to worry about, it’s very easy for them to just surround it and beat it to death with their preferred pointy, slice-y, or blunt objects.

So how do we fix this problem? Well, you could try letting the skeleton attack more frequently, but that still has the same kind of problems as the normal skeleton. It can only hit a few targets per turn, and the party can still gang up on it and kill it quickly.

Letting the skeleton deal enough damage to take down an opponent in one or two rounds isn’t very fun either, in terms of combat. If it has to use all it’s attacks to take down an opponent, then the rest of the opponents can just whale on it until it drops. If it’s strong enough to knock out an opponent with one attack, then that can leave players feeling cheated if they didn’t get to do anything before getting taken out of the fight.

Alternatively, you can give it more health. Then it won’t die as quickly and can attack more players. But since the fight still has to be balanced, you can’t give the skeleton more health and more damage, as then it might become too strong of an enemy, which means it ends up doing the same damage but having more health. In this scenario, the skeleton isn’t a threatening, dangerous enemy, it’s just a sack of hit points that takes more time to kill.

Is there anything that can be done? Or are giant monsters ultimately just cool to look at? I say that with just a bit of extra creativity, giant monsters like this can become interesting fights. I’ll go over how I would go about doing this in part 2.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Problematic Players (Pt. 2)

We’ve looked at the players, now it’s time to turn the accusatory finger around and point at the other side of the screen. Dungeon Masters are far from infallible, and here are some of the worst ways that they can fail.

THE “STORYTELLER”

This DM has a story they want to tell, with or without the players’ input. They’ll do whatever it takes to force the players down a specific route. Also known as railroading, this method of DMing is widely regarded as a sign of a bad DM. This DM will often punish those who try to stray from the path with character injury or even death. There can be no choices in this DM’s game aside from the ones they want you to make.

THE NAYSAYER

Somewhat similar to the Storyteller, this DM has a very strict definition of what is and isn’t allowed in their game. Did you want to keep a bandit alive to interrogate him, only to find out that someone else is trying to silence him? With the Naysayer as your DM, there’s no chance that bandit is living long enough to tell you anything. What the DM says, goes, and there’s nothing that you can do to change that, logic be damned.

THE ANTAGONIST

This DM is out to get the players, actively trying to kill their characters and generally make life hard for them. The group is no longer playing a game together, the players are fighting the DM for their characters’ very survival. In the right group or the right game, this can work. For example, the pre-generated dungeon The Tomb of Horrors is designed to kill as many players as possible. Unfortunately, the Antagonist shows up in regular games all too often, making playing the game an ordeal for those players, rather than a good time.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Problematic Players (Pt. 1)

Every bunch has a few bad bananas, and gamers are no different. There are some well-known archetypes, so to speak, of problematic players, as well as DMs. Here are a few from the player side of the equation.

THE MAIN CHARACTER

This player wants their character to be the focus of the story at all times. They’ll insert their character into unrelated conversations and absolutely need to be the leader of the group. If they aren’t the leader, this player will often ignore the group’s plans and desires and do whatever they want to do. If a DM isn’t careful, this player can end up bulldozing the game in a completely new direction, despite any complaints or reservations that anyone else at the table might have. This is unfortunately a pretty common type of player, due to D&D’s inherent nature as a fantasy game making it prone to becoming escapist fantasy wish fulfillment.

THE POWER PLAYER

This player wants to make their character the strongest they can possibly be, often at the expense of the story and the other players. They’ll hoard all the gold and magic items, and they almost certainly have a plan to make their character as game-breaking as possible. Of course, everyone wants their character to be strong, but when a character is so strong that the DM can’t properly challenge them without putting the other characters way out of their depth, then it becomes a problem.

THE META GAMER

This player treats D&D as a game and nothing more, making decisions based on what they, the player, know, ignoring the fact that their character would have no way of knowing those things. If the player knows that vampires are going to attack the town, they’ll have their character bring garlic, crosses, holy water, and stakes with them to the bar, “just in case”. If your group wants to play D&D as something to be “won,” then this type of character isn’t necessarily problematic, but they often take the RP out of the RPG.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHO TO PLAY WITH

Now that we’ve explored WHAT TO PLAY it’s time to discuss WHO TO PLAY WITH. Finding the right group of players is tantamount to having a good time with Dungeons and Dragons. If the chemistry isn’t there, it’ll be less fun for everyone involved. So what kind of people make up that “right group?”

Now ideally, you’ll be able to find a group to play with super easily, and everyone will be very enthusiastic and invested in your campaign, and everyone will get along with everyone else. Unfortunately, there’s no group that’s perfect. The ideal, realistic group is made of members with a few key qualities.

Firstly, they should be enthusiastic. If they genuinely want to play, they’ll tend to work with the DM more to make sure that the game is a good experience overall. In addition, it’s just more fun that way! Enthusiasm is infectious, and the more you throw yourself into the game, the more fun it is.

Secondly, they should be willing to learn and accept criticism. It’s okay if a player makes mistakes or occasionally acts in a manner that makes the game not fun, as long as he’s willing to listen when somebody (preferably the DM) talks to him about these things. Sometimes people just don’t know any better, and if they fix the problems, then it’s all good.

Thirdly, they should be respectful, or at least willing to learn to be respectful. D&D is a collaborative game. If someone in the group is constantly on his phone, or talking over other people, or being directly rude to other people, it can ruin the experience for everyone.

If a player doesn’t have most or all of these characteristics, that’s not a person that you want to be playing with. And if it turns out that you thought they were okay, but they actually aren’t, it’s well within your rights as a DM and a player of the game to take him aside and talk to them. If he still keeps up this kind of behavior, you are under no obligation to allow him to continue playing with you. It may seem harsh, but you have to do what it takes to keep things enjoyable.

As for where to find these players, there are plenty of options. You can ask people you know, obviously, but if that doesn’t pan out, there are almost certainly willing players at your Friendly Local Game Store (FLGS), or even online if need be. All you have to do is ask around, and you’ll find a group in no time.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Running a Homebrew Campaign

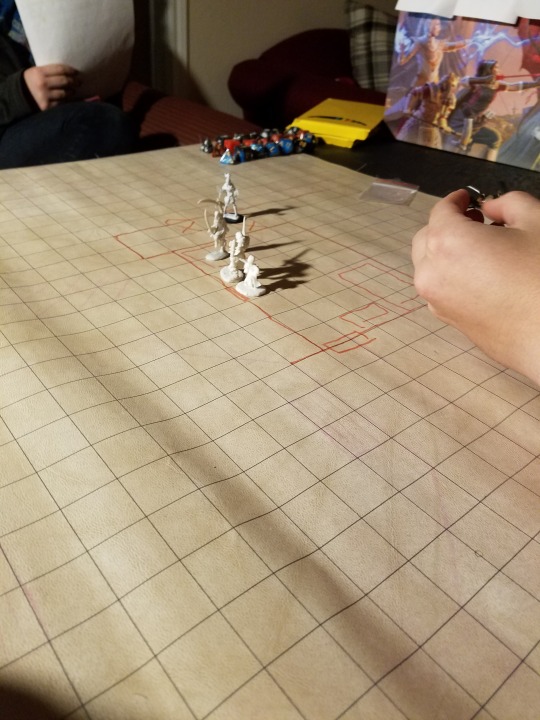

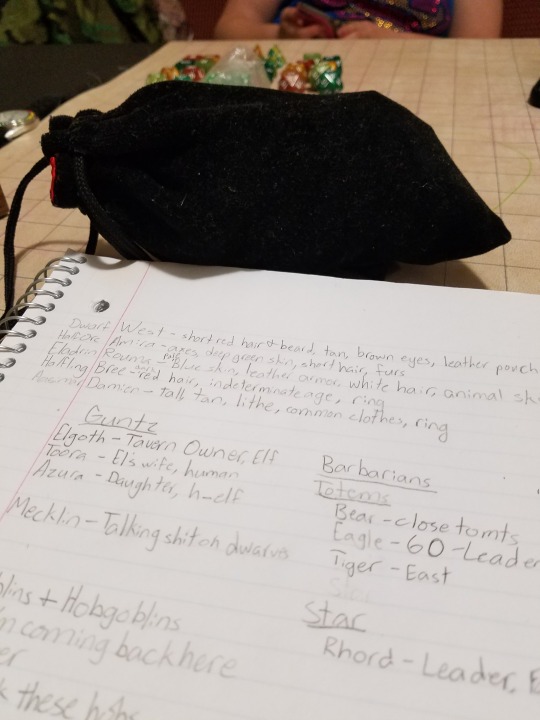

Finally, the homebrew campaign. This is by far the most in-depth to run, but the concept is so massively broad that talking about it is a little tricky. Still, I’m going to do my best, and hopefully you’ll get some use out of my ramblings.

So you’re feeling bold, or you want to exercise those creative muscles, or maybe you just have a lot of time on your hands and you want to run a game of D&D. If any or all of these apply to you, then a homebrew campaign might be just what you’re looking for. In a homebrew campaign, the story and setting are entirely up to you. Do you want to have a traditional fantasy story, but with a lot more freedom and character development than is often possible in adventure modules or one-shots? Homebrew campaign. Do you want to have a deep political drama focusing on espionage and social situations rather than combat? Homebrew campaign. Do you want one of the factions in that political drama to be a race of airship-riding otters? Homebrew campaign.

The biggest allure of a homebrew campaign is far and away the level of freedom that it offers for the DM. Since there’s no story set in stone except the one that the DM wants to tell, any interesting plot hook or character backstory can be seized upon and expanded. Maybe in their quest to find some magic artifact, the party happens across a tribe of goblins being enslaved by orcs. Instead of fighting, they manage to talk their way out of it and now have the choice of moving on to find the relic, or freeing the goblins from their enslavement. This kind of freedom of choice is much more difficult to accomplish in a module or a one-shot.

A homebrew campaign does have one major drawback, though: time. In order for this freedom to be accomplished, the DM has to put in exponentially more work than they would for one of the other game types. Nothing is laid out for you, so you have to create everything. Every enemy, every non-player character, every country, state, and city, come from the DM’s imagination. Of course, as DM, you can take inspiration from other sources, but that doesn’t negate the effort that goes into putting all that information together.

Still, if you’ve got the time and creativity for it, a homebrew campaign can be incredibly rewarding. There’s nothing quite like watching your players explore a world of your making… before thoroughly screwing it up.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

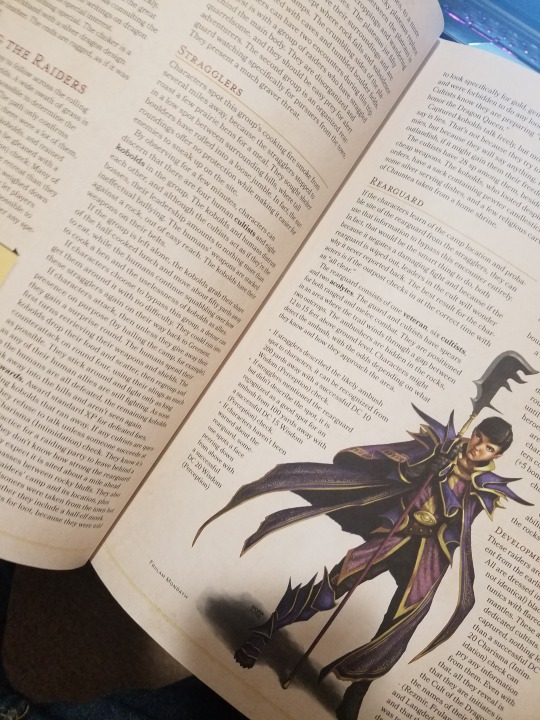

Running a Module

The next type of game that I’ll be going over is the adventure module. In an earlier post, I said that adventure modules were pre-generated stories published by Wizards of the Coast, but that’s not entirely true. Upon looking into it further, I found many adventure modules published by different companies. These modules were often set in other established settings, such as Middle-earth from Lord of the Rings or Thedas from the Dragon Age games. If you’re a fan of some property, it may be worthwhile to check out some of these unofficial modules.

If you’re strapped for time or inspiration to make a campaign of your own, never fear—adventure modules have your back. Adventure modules—we’ll call them modules from here on out—are campaigns written by professionals, ready and waiting for your group to play. Modules usually consist of a single major plot thread, with some secondary objectives or story elements along the way. Modules also usually have a set range of levels that it will take the players through. If a module says “for characters of levels 1—7, that means the player characters will start at level 1, and be level 7 by the time they finish the module.

As preparation goes, there’s very little that you as a DM have to do other than reading the module and understanding what comes next, although, to be fair, that level of memorization is nothing to sneeze at. Even the more linear modules can have upward of 80 pages of text. The DM should always have an understanding of not only what’s happening to the players, but what’s happening around them. As always, players will be players, and will sometimes go off the rails. As a DM, you have to know what the book says might happen, but also be ready to improvise when your players ask you a question that the book doesn’t cover (it’ll happen a lot).

All that said, with the wide variety of adventure modules, whether your group wants to fight off a cult working for the return of an evil dragon god, or free a country from the rule of a wicked vampire, you’re sure to find a module that’s just right for your group.

Finally, we’ll go over the homebrew campaign to wrap up this discussion.

-Grey

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

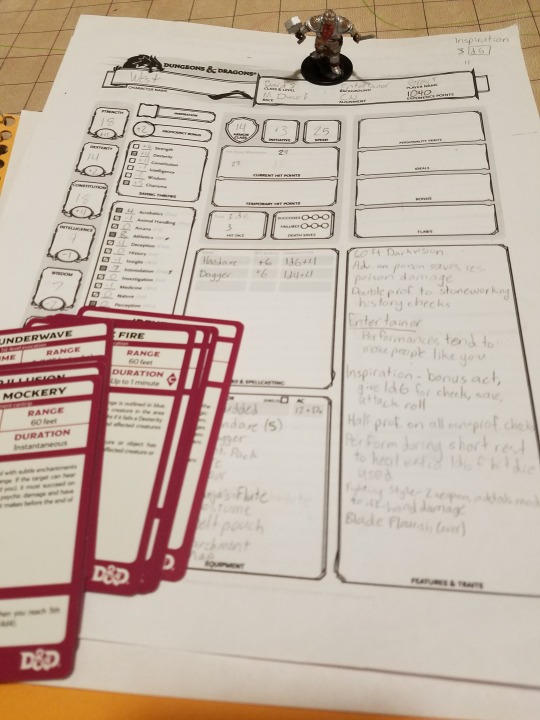

Running a One-Shot

Yep, it’s been a while. I didn’t intend for this blog to fall by the wayside, but things happen, and well, here we are. In the last post, I talked about three different types of Dungeons and Dragons games, and which one might appeal to you. Now, I’ll be going a little more in-depth with what it means to run each of them, starting with the one-shot.

Now, as a matter of point, the phrase “one-shot” is a little bit misleading. One-shot games can be games that are run in one session, but a one-shot is really just a single, self-contained adventure. These stories often begin with a group of adventurers (the players) being hired to complete some job. This can be anything from exploring old ruins to exterminating an infestation of monsters. Whatever the story, a one-shot rarely lasts more than three or four sessions and should have a satisfying and conclusive ending.

One-shot games are the easiest of the three types to prepare for. Since the goal in a one-shot is usually clearly defined, it’s much easier to keep your players on target. That being said, players will be players, and that means they’re going to be hard to control no matter what. To maintain flexibility, I find it helps to have an outline of what you want to happen, but don’t get too hung up on the details.

We’ll use the following scenario as an example.

The party has been approached by a resident of a small mining town in the mountains. Lately, monsters have been coming down the mountains more frequently and attacking miners on their way to and from the mines. Without the revenue that the mines bring in, the town will collapse. They need the party’s help!

In this situation, you as a DM have to decide on a few things.

1. What type of monsters are coming down the mountain? Having a good variety to choose from allows you to throw a few fights at the players on their way to figuring out the root of the problem, as well as adjust the difficulty of the game on the fly, based on how well the players are doing.

2. Why are the monsters coming down the mountain? If this is a new problem, there has to be a cause. What the cause actually is, is up to you. It could be an oncoming storm or natural disaster, it could be a stronger monster that has made the peak it’s territory, or it could be something else. The choice is yours.

Beyond these things, you can plan however much you want. If you want to go into detail about the town’s political structure and name every villager, you can go right ahead and do that. Likewise, if you want to create characters as the players meet them and interact with them, that’s also perfectly fine. In the end, it comes down to the type of DM you are. Personally, I prefer a more improvisational style of DMing, but it’s all personal preference.

Up next, we’ll be looking at running an adventure module.

-Grey

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

STARTING A GAME

The first topic I’ll be covering is mostly for new DMs: the process of starting a game of DnD, and things to keep in mind throughout that process. With that in mind, there are two things to consider first when you decide you want to run a game: what do you want to play, and who do you want to play with? This first series of posts will be dedicated to

WHAT YOU WANT TO PLAY

There are many different ways to play DnD. Some people like sprawling epics born straight from the imagination of the Dungeon Master, and others like stories that take place within one of the official DnD settings. Still others prefer smaller stories—stories that can be told over the course of only a few sessions of playtime. It’s up to you what you want to play, but you have to have a clear idea in mind before you start playing. A good seventy percent of being a DM is about preparation.

So should you play option one—the homebrew campaign? Option two—the adventure module? Or option three—the one-shot or mini-campaign? Well, that depends largely on how much time you have available. If you want to play, but time is a commodity in your life, you may want to run a one-shot. These are simple to set up and fun to play, without involving the weeks of planning that go into the others. If you have a fair amount of time, but don’t have the time to (or just don’t want to) create a world from scratch, it’s worth looking into an adventure module. These are books published by Wizards of the Coast, and contain all the information you need to run an adventure. Such modules include Storm King’s Thunder, Princes of the Apocalypse, and Hoard of the Dragon Queen, to name a few.

If you’ve got time to spare and you’re feeling ambitious and creative, a homebrew campaign might be to your liking. While this requires more work on your part, it can be very rewarding to see players interact with and enjoy a world of your making.

Next, we’ll be taking a deeper look at what it means to run each of these types of adventures, and the work that needs to go into it beforehand. See you then!

-Grey

#dnd#d&d#dungeons and dragons#Tabletop role-playing game#tabletop rpg#rpg#ttrpg#dndm tips#starting the game

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone, and welcome to this Dungeons and Dragons blog, where I’ll be writing down my experiences with running the game (5th edition D&D is my game of choice, but I dabble in some other systems) and offering tips and tricks to anyone who wants to listen.

Before we start, though, I should give a small disclaimer: I am no encyclopedic source of knowledge on the game itself, nor do I have any authority to interpret rules or scenarios. I’m no professional—leave that to people like Matt Mercer and Chris Perkins. All that I am is an avid fan of D&D and a part-time dungeon master. I’ve fancied myself a storyteller all my life, but I’ve only been playing tabletop RPGs for about 4 years. If you listen to my advice—and really, anyone’s advice about this topic—listen to it with thoughts toward your own games. While you read, ask yourself the following questions: “Does the advice he’s giving here work with my players?” and “Does it work with my campaign?” If the answer to either is “no,” then you need to ask “Is it possible to take parts of the advice and shape it to my situation?”

There is no end-all, be-all to DMing. My experiences are, and will continue to be, different from your own, and that’s an amazing thing. D&D is about creativity. It’s about creating a unique experience for you and your friends, and all kinds of factors shape what exactly that experience ends up being. If you want to listen to me, whether it’s to get advice on overcoming challenges in your own DM style, to hear about the experiences of a D&D group separate from your own, or for some other reason entirely, I welcome you with open arms. Over the next few months (and maybe beyond) I hope that I can help you learn, or at the very least, give you an entertaining diversion for a little while.

May your dice always roll well!

-Grey

#dungeons and dragons#dnd#dnd 5e#d&d#d&d 5e#rpg#ttrpg#tabletop role-playing game#dm tips#dungeon master#advice#introduction

2 notes

·

View notes