Link

0 notes

Text

Georgian traditional clothing

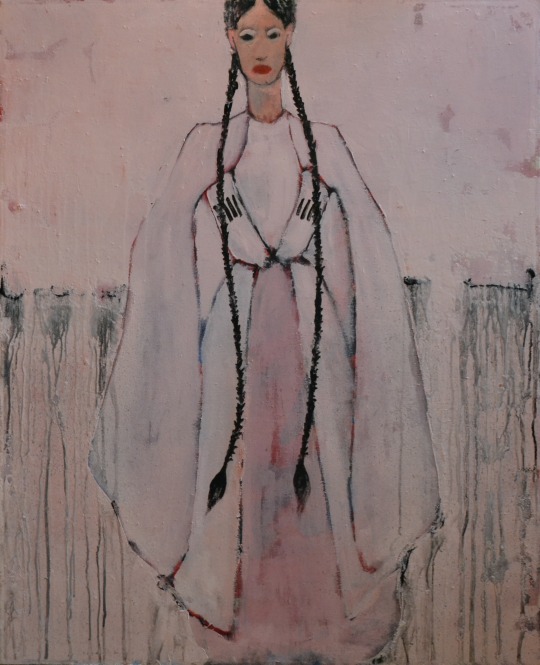

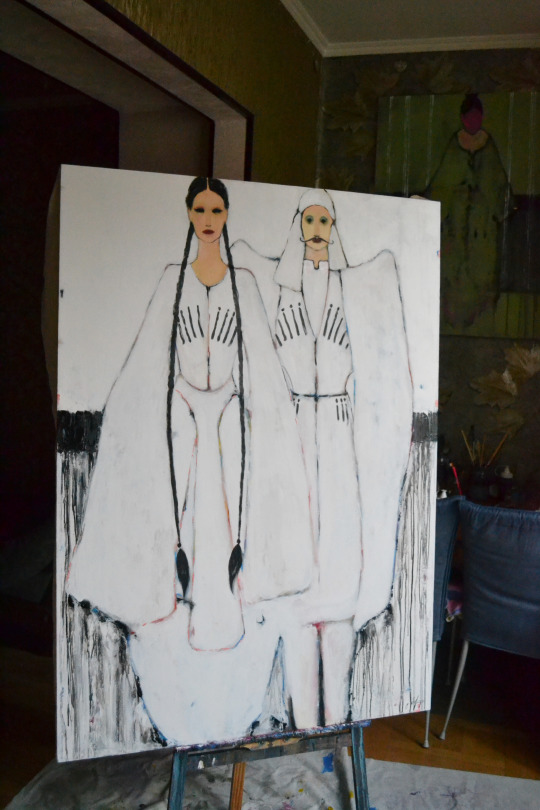

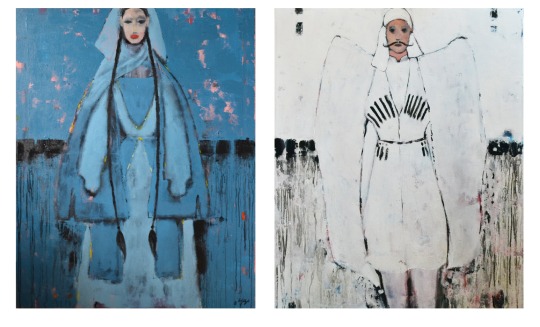

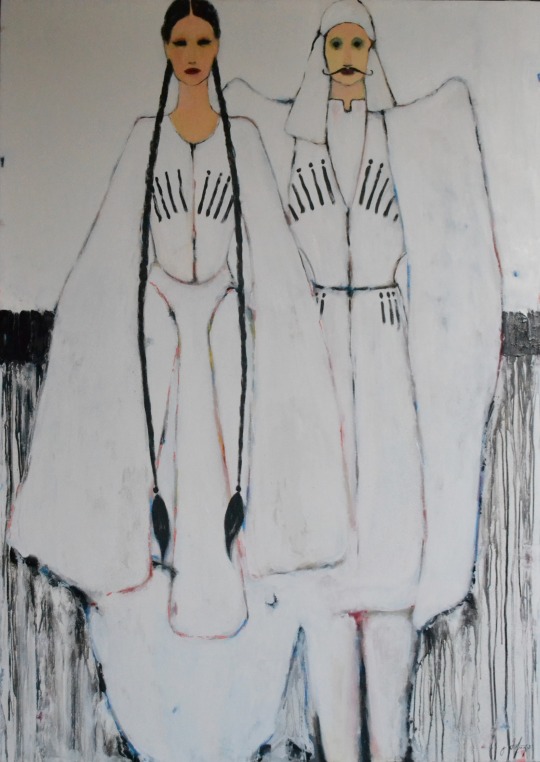

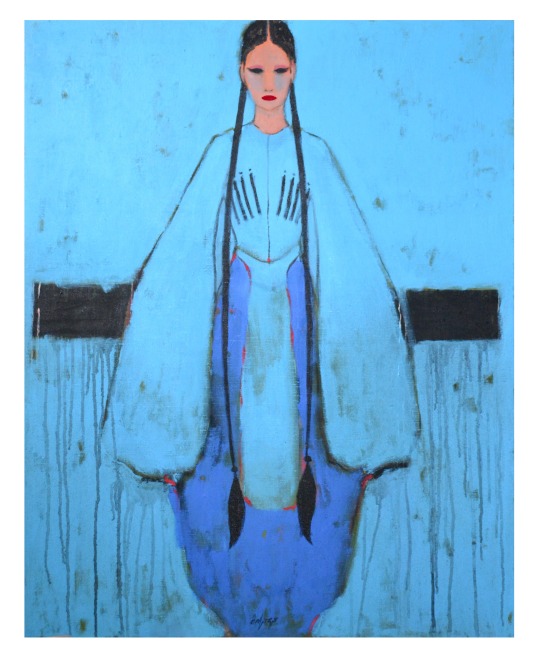

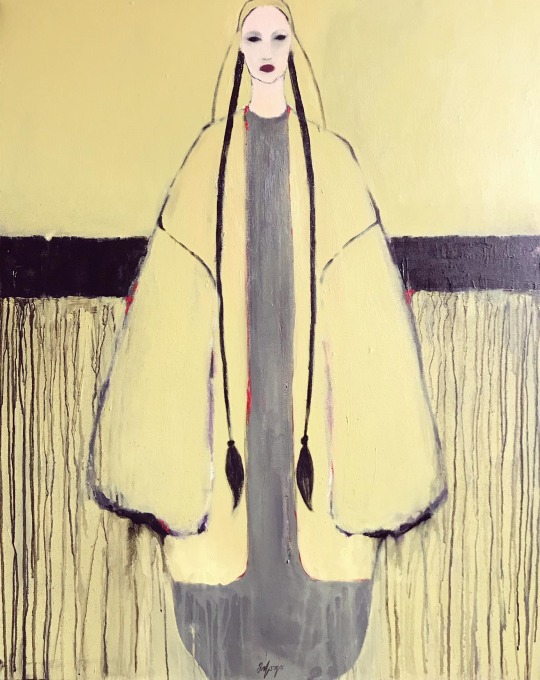

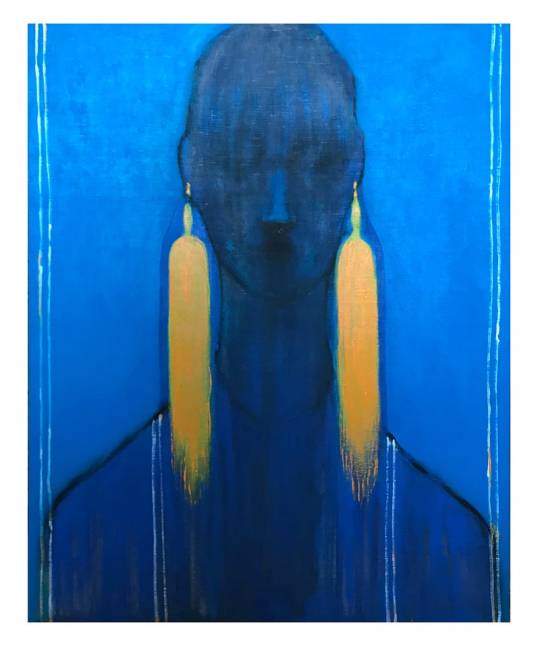

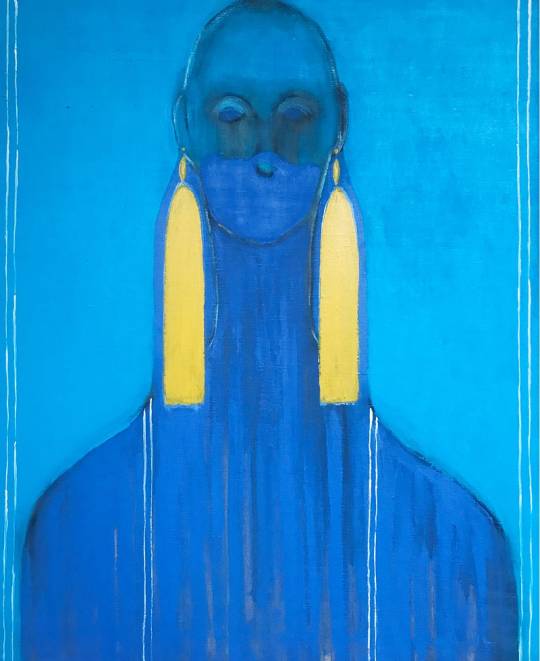

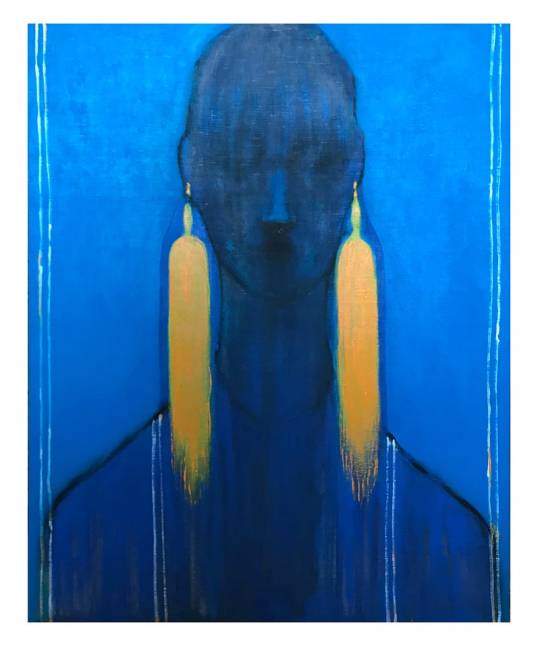

The Roots series. Traditional clothing by Gela Mikava

Traditional lifestyles developed around the local climate and terrain, which in turn precipitated the creation of conventional clothing. Although every region of Georgia possessed its own distinct attire, an overarching similarity was seen in the chokha (Russian: cherkeska), a wool coat typically worn by men and noted for the cartridge holders sewn onto the chest. Women’s clothing was much more varied between the regions, particularly in the remote mountain communities.

Prince Vakhushti Batonishvili (1696–1757) paved the way in the study of traditional Georgian clothing, giving particular attention to the attire from medieval times and that of his own generation. Foreign travelers such as Arcangelo Lamberti and Jean Chardin also made notable contributions to the topic. The latter travelled to Georgia in the 1670s, and his remarkably detailed notes provide valuable insights into local clothing of that time as well as the similarities and differences between Persian, Georgian and European attire.

Thanks to these and other such historical records, a picture of traditional Georgian clothing from each region of the country may be pieced together today.

Traditional Clothing of Kartli-Kakheti

According to Vakhushti Batonishvili, people from Kakheti and Kartli had similar clothing styles. For men in Kartli-Kakheti, the primary piece of apparel was the chokha. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was longer than that of neighboring Khevsureti and had a triangular opening at the neck to reveal an inner cloth. The chokha, worn without a belt by men, included a slitted skirt and miniature pockets on either side of the chest that were traditionally loaded with bullets. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was usually tan, blue, black or red in color.

In keeping with conservative Georgian culture at that time, women in Kartli-Kakheti wore long dresses with beautiful ornate bodices. The dress was tightened at the waist with a richly decorated belt that draped almost to the end of the skirt. The most important aspect of the outfit was the headdress, which was defined by a triangular white veil of tulle, a velvet rim and a dark headscarf.

Traditional Clothing of Pshav-Khevsureti

Clothing in Georgia’s mountain regions was made of a durable wool fabric that provided protection against harsh alpine conditions. Despite its practical nature, the apparel was always beautifully decorated, as women in Pshav-Kvevsureti were trained from childhood in wool processing and dyeing.

Kvevsureti’s chokha, known as talavari, were short with slits running down to the waist and a beautifully decorated fabric affixed to the front. Men’s outfits typically consisted of knitted pants called pachichebi, woven fiber shoes known as tatebi and chokha with colorful religious symbols embroidered on the front.

Traditional women’s dresses in Khevsureti were called sadiatso. Sadiatso were knee-length dresses decorated with baubles and sophisticated geometric patchwork. Just like their Kartli-Kakhetian neighbors, women in Khevsureti wore a headdress. Traditional Khevsur headdresses were greatly admired and decorated with cross-shaped ornamental patterns. Pshav and Khevsur women would also wear silver coins and cross necklaces.

Traditional Clothing of Tusheti

Tusheti’s highland inhabitants were known for their use of wool in making clothes, shoes and rugs, with solar symbols and crosses regularly employed in their remarkable clothing and jewelry designs.

Both women and men in Tusheti wore colorfully knitted shoes called chitebi. Men’s chitebi were plainer with polka dots, while women’s chitebi were striped and multicolored. When making chitebi, the weaver would start from the tip of the shoe and continue backwards towards the heel. Chitebi shoes also played a role in local superstition: On a Wednesday during Lent, mothers would put male chitebi under the pillow of their daughters right before they went to sleep, in the hope that they would see their future husband in their dreams.

Traditionally, a Tushetian woman wore a black headscarf which reached down to her knees, a loose-fitting dress underneath her robe and an outer garment adorned with jewelry across the chest. Men’s clothing consisted of a chokha and a warm black hat.

Traditional Clothing of Svaneti

No discussion of Georgian traditional clothing would be complete without mentioning Svaneti’s famous hats. Svan hats were usually gray with black seams. Each hat was made from 200 grams of sheep’s’ wool and took about 30 hours to complete. The black seams were cross-shaped and reflected the popular Svan greeting , “May the cross protect you”. Svan hats were valued for providing warmth from winter’s chill and respite from summer heat.

Traditional Svan clothing consisted of a shirt, chokha, trousers and Svan hat. Women wore a woolen dress and headdress adorned with earrings and jewelry, while those who were wealthy also wore silk shirts and a velvet cloak.

Traditional Clothing of Racha

Iakob Gogebashvili, a leading 19th-century Georgian pedagogue, described female outfits from Racha in one of his writings, noting that they wore the chokha and an akhalukhi undershirt.

Women’s clothing from Racha also attracted the attention of many foreign travelers. In 1874, German scientist Dr. W. B. Pfaff could not hide his astonishment towards women’s clothing in Racha, exclaiming “I was amazed by the variety of women’s clothing, which in many ways reminds me of Anatolia”. In 1874, English explorer Philip Grove, upon seeing three local women, also noted “They wore short dresses and trousers…with grace”.

Apparently men’s attire in Racha was less noteworthy, as little information has reached us today regarding their traditional style of dress.

Traditional Clothing of Adjara and Guria

Traditional Georgian men’s clothing in the western Adjara and Guria provinces differed dramatically from that of eastern Georgia. The typical men’s outfit in Guria-Adjara, Samegrelo and the whole of southwest Georgia was the chakura, which consisted of a short waist-length chokha, wide-brimmed trousers and a colorful silk belt.

Throughout the ages, women in Adjara have worn three types of dresses. Zubun-faraga, the oldest of the three, derived its name from the Turkish word zubuni, meaning “coat”. The dress was long and hemmed in at the waist, with special attention paid to lavish embellishments on the bodice. A zubun-faraga dress can be seen today on display at the Simon Janashia Museum in Tbilisi.

The zubun-faraga dress was gradually replaced by the datexili dress, which was recognizable by its long, wrinkled appearance and multicolored threads worked into the fabric. It was tightly fitted to the body and had hidden pockets sewn into the wrinkles. In later years, the datexili dress evolved into a new variation known as the forka dress.

Traditional Georgian Shoes

Traditional Georgian shoes were typically made using muted colors of black, red, green and light brown. The 17th-18th century Georgian diplomat Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani mentions several types of local shoes in his writings:

Tsugha were worn at home by both men and women. They were sewn from leather of various colors and the edges beautifully decorated.

Kalamani were common leather shoes worn by villagers beginning in the 10th-11th centuries.

Mogvi were tall leather boots worn by kings and nobles.

Additional Information

The best places to see Georgian traditional clothing today are at the Art Palace of Georgia (formerly known as the Museum of Cultural History) and at the Simon Janashia Museum, both located in Tbilisi. Traditional clothing, which has slowly been making a comeback in the 21st century, is also sometimes donned at Georgian traditional weddings and cultural events.

The Day of National Dress in Georgia is a recently established holiday celebrated on the 18th of May. In commemoration of their heritage, Georgian dancers and ordinary people alike dress in national costumes and march across the city to demonstrate the beauty of traditional Georgian attire. If you are visiting Georgia during this time, be sure to join the celebration to become familiar with diverse costumes from every region of Georgia!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Georgian traditional clothing is an apt reflection of the cultural heritage of Georgia’s native peoples. Within the conventional attire of its national clothing, the Georgian people’s adaptability, devotion to tradition and appreciation of aesthetic beauty is conveyed.

Traditional lifestyles developed around the local climate and terrain, which in turn precipitated the creation of conventional clothing. Although every region of Georgia possessed its own distinct attire, an overarching similarity was seen in the chokha (Russian: cherkeska), a wool coat typically worn by men and noted for the cartridge holders sewn onto the chest. Women’s clothing was much more varied between the regions, particularly in the remote mountain communities.

Prince Vakhushti Batonishvili (1696–1757) paved the way in the study of traditional Georgian clothing, giving particular attention to the attire from medieval times and that of his own generation. Foreign travelers such as Arcangelo Lamberti and Jean Chardin also made notable contributions to the topic. The latter travelled to Georgia in the 1670s, and his remarkably detailed notes provide valuable insights into local clothing of that time as well as the similarities and differences between Persian, Georgian and European attire.

Thanks to these and other such historical records, a picture of traditional Georgian clothing from each region of the country may be pieced together today.

Traditional Clothing of Kartli-Kakheti

According to Vakhushti Batonishvili, people from Kakheti and Kartli had similar clothing styles. For men in Kartli-Kakheti, the primary piece of apparel was the chokha. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was longer than that of neighboring Khevsureti and had a triangular opening at the neck to reveal an inner cloth. The chokha, worn without a belt by men, included a slitted skirt and miniature pockets on either side of the chest that were traditionally loaded with bullets. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was usually tan, blue, black or red in color.

In keeping with conservative Georgian culture at that time, women in Kartli-Kakheti wore long dresses with beautiful ornate bodices. The dress was tightened at the waist with a richly decorated belt that draped almost to the end of the skirt. The most important aspect of the outfit was the headdress, which was defined by a triangular white veil of tulle, a velvet rim and a dark headscarf.

Traditional Clothing of Pshav-Khevsureti

Clothing in Georgia’s mountain regions was made of a durable wool fabric that provided protection against harsh alpine conditions. Despite its practical nature, the apparel was always beautifully decorated, as women in Pshav-Kvevsureti were trained from childhood in wool processing and dyeing.

Kvevsureti’s chokha, known as talavari, were short with slits running down to the waist and a beautifully decorated fabric affixed to the front. Men’s outfits typically consisted of knitted pants called pachichebi, woven fiber shoes known as tatebi and chokha with colorful religious symbols embroidered on the front.

Traditional women’s dresses in Khevsureti were called sadiatso. Sadiatso were knee-length dresses decorated with baubles and sophisticated geometric patchwork. Just like their Kartli-Kakhetian neighbors, women in Khevsureti wore a headdress. Traditional Khevsur headdresses were greatly admired and decorated with cross-shaped ornamental patterns. Pshav and Khevsur women would also wear silver coins and cross necklaces.

Traditional Clothing of Tusheti

Tusheti’s highland inhabitants were known for their use of wool in making clothes, shoes and rugs, with solar symbols and crosses regularly employed in their remarkable clothing and jewelry designs.

Both women and men in Tusheti wore colorfully knitted shoes called chitebi. Men's chitebi were plainer with polka dots, while women’s chitebi were striped and multicolored. When making chitebi, the weaver would start from the tip of the shoe and continue backwards towards the heel. Chitebi shoes also played a role in local superstition: On a Wednesday during Lent, mothers would put male chitebi under the pillow of their daughters right before they went to sleep, in the hope that they would see their future husband in their dreams.

Traditionally, a Tushetian woman wore a black headscarf which reached down to her knees, a loose-fitting dress underneath her robe and an outer garment adorned with jewelry across the chest. Men's clothing consisted of a chokha and a warm black hat.

Traditional Clothing of Svaneti

No discussion of Georgian traditional clothing would be complete without mentioning Svaneti’s famous hats. Svan hats were usually gray with black seams. Each hat was made from 200 grams of sheep’s’ wool and took about 30 hours to complete. The black seams were cross-shaped and reflected the popular Svan greeting , “May the cross protect you”. Svan hats were valued for providing warmth from winter’s chill and respite from summer heat.

Traditional Svan clothing consisted of a shirt, chokha, trousers and Svan hat. Women wore a woolen dress and headdress adorned with earrings and jewelry, while those who were wealthy also wore silk shirts and a velvet cloak.

Traditional Clothing of Racha

Iakob Gogebashvili, a leading 19th-century Georgian pedagogue, described female outfits from Racha in one of his writings, noting that they wore the chokha and an akhalukhi undershirt.

Women’s clothing from Racha also attracted the attention of many foreign travelers. In 1874, German scientist Dr. W. B. Pfaff could not hide his astonishment towards women’s clothing in Racha, exclaiming “I was amazed by the variety of women's clothing, which in many ways reminds me of Anatolia". In 1874, English explorer Philip Grove, upon seeing three local women, also noted “They wore short dresses and trousers…with grace”.

Apparently men’s attire in Racha was less noteworthy, as little information has reached us today regarding their traditional style of dress.

Traditional Clothing of Adjara and Guria

Traditional Georgian men's clothing in the western Adjara and Guria provinces differed dramatically from that of eastern Georgia. The typical men’s outfit in Guria-Adjara, Samegrelo and the whole of southwest Georgia was the chakura, which consisted of a short waist-length chokha, wide-brimmed trousers and a colorful silk belt.

Throughout the ages, women in Adjara have worn three types of dresses. Zubun-faraga, the oldest of the three, derived its name from the Turkish word zubuni, meaning “coat”. The dress was long and hemmed in at the waist, with special attention paid to lavish embellishments on the bodice. A zubun-faraga dress can be seen today on display at the Simon Janashia Museum in Tbilisi.

The zubun-faraga dress was gradually replaced by the datexili dress, which was recognizable by its long, wrinkled appearance and multicolored threads worked into the fabric. It was tightly fitted to the body and had hidden pockets sewn into the wrinkles. In later years, the datexili dress evolved into a new variation known as the forka dress.

Traditional Georgian Shoes

Traditional Georgian shoes were typically made using muted colors of black, red, green and light brown. The 17th-18th century Georgian diplomat Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani mentions several types of local shoes in his writings:

Tsugha were worn at home by both men and women. They were sewn from leather of various colors and the edges beautifully decorated.

Kalamani were common leather shoes worn by villagers beginning in the 10th-11th centuries.

Mogvi were tall leather boots worn by kings and nobles.

Additional Information

The best places to see Georgian traditional clothing today are at the Art Palace of Georgia (formerly known as the Museum of Cultural History) and at the Simon Janashia Museum, both located in Tbilisi. Traditional clothing, which has slowly been making a comeback in the 21st century, is also sometimes donned at Georgian traditional weddings and cultural events.

The Day of National Dress in Georgia is a recently established holiday celebrated on the 18th of May. In commemoration of their heritage, Georgian dancers and ordinary people alike dress in national costumes and march across the city to demonstrate the beauty of traditional Georgian attire. If you are visiting Georgia during this time, be sure to join the celebration to become familiar with diverse costumes from every region of Georgia!

#gela mikava#emerging art#emerging artist#conceptual#modern#mixed media#traditional#colorful#bestseller#newstyle

0 notes

Text

Types of Georgian dance

Kartuli (ქართული)

Kartuli dance is a romantic/wedding dance. It is performed by a dance couple. During the dance, the man is not allowed to touch the woman and must keep a certain distance from his partner. The man’s upper body is motionless at all times. It shows that even in love, men must control their feelings. The man focuses his eyes on his partner as if she were the only woman in the whole world. The woman keeps her eyes downcast at all times and glides on the rough floor as a swan on the smooth surface of a lake. There have been only a few great performers of Kartuli including Nino Ramishvili, Iliko Sukhishvili, Iamze Dolaberidze, and Pridon Sulaberi

Khorumi (ხორუმი

The dance was originally performed by only a few men. However, over time it has grown. In today’s version of Khorumi, 30–40 dancers can participate, as long as the number is odd. The dance has four parts: a search for a campsite, the reconnoiter of the enemy camp, the fight, and the victory and its celebration. It is strong and simple but distinctive movements and the exactness of lines create a sense of awe on stage.

The dance incorporates the themes of search war, and the celebration of victory as well as the courage and glory of Georgian soldiers. Khorumi is traditionally accompanied by instruments and is not accompanied by clapping. Drum (doli) and the bagpipe (chiboni) are two key instruments to accompany Khorumi. Another unique element of Khorumi is that it has a specific rhythm, based on five beat meter (3+2).

Acharuli (აჭარული)

Acharuli also originated in Acharuli, which is where it gets its name. Acharuli is distinguished from other dances with its colorful costumes and the playful mood that simple but definite movements of both men and women create on stage. The dance is characterized with graceful, soft, and playful flirtation between the males and females. Unlike Kartuli, the relationship between men and women in this dance is more informal and lighthearted.

Partsa (ფარცა)

Partsa originated in Guria and is characterized by its fast pace, rhythm, festive mood, and colorfulness. Partsa mesmerizes the audience with not only speed and gracefulness, but also with “live towers.”

Kazbeguri (ყაზბეგური)

Kazbeguri originated in the Kazbegi Municipality in Caucasus Mountains of Georgia. The dance was created to portray relatively cold and rough atmosphere of the mountains, shown through the vigor and the strictness of the movements and foot stomping. This dance is performed mainly by men. Costumes are a long black coloured shirt, black trousers, a pair of black boots, and black headgear. Musical instruments include bagpipes, a panduri, a changi, and drums.[3]

Khanjluri (ხანჯლური)

Khanjluri is based on the idea of competition. Khanjluri is one of those dances. In this dance, shepherds, dressed in red chokhas (traditional men’s wear) compete with each other in the usage of daggers and in performing complicated movements. One performer replaces another, and the courage and skill overflow on stage. Since Khanjluri involves daggers and knives, it requires tremendous skill and practice on the part of the performers.

Khevsuruli (ხევსურული)

This mountain dance unites love, courage, respect for women, toughness, competition, skill, beauty, and colorfulness into one performance. The dance starts out with a flirting couple. Unexpectedly, another young man appears, also seeking the hand of the woman. Vigorous fighting between the two men and their supporters ensues. The quarrel is stopped temporarily by the woman’s veil. Traditionally, when a woman throws her head veil between two men, all disagreements and fighting halts. However, as soon as the woman leaves the scene, the fighting continues. The young men from both sides attack each other with swords and shields. On some occasions, one man has to fight off 3 attackers. At the end, a woman (or women) comes in and stops the fighting with her veil once again. However, the finale of the dance is “open” –meaning that the audience does not know the outcome of the fighting. Khevsuruli is very technical and requires intense practice and utmost skill in order to perform the dance without hurting anyone.

Mtiuluri (მთიულური)

Mtiuluri is also a mountain dance. Similar to Khevsuruli, Mtiuluri is also based on competition. However, in this dance, the competition is mainly between two groups of young men and is a celebration of skill and art. At first, groups compete in performing complicated movements. Then, the girl’s dance, which is followed by an individual dancer’s performance of amazing “tricks” on their knees and toes. At the end, everyone dances a beautiful finale. This dance is reminiscent of a festival in the mountains.

Simdi and Khonga

Ossetian folk dances. The costumes in both dances are distinguished with long sleeves. The headwear of both the women and the men are exceptionally high. However, in Khonga or Invitation Dance (Ossetian Wedding Dance), men dance on demi-pointe, entirely on the balls of their feet. Khonga is performed by a few dancers and is characterized by the grace and softness of the movements. Simdi is danced by many couples. The beauty of Simdi is in the strict graphic outline of the dance, the contrast between black and white costumes, the softness of movements, and the strictness of line formations.

Kintouri (კინტოური) and Shalakho

Kintouri portrays the city life in old Tbilisi. The dance takes its name after “Kintos” who were small merchants in Tbilisi. They wore black outfits with baggy pants and usually carried their goods on their heads around the city. When a customer chose goods, a kinto would take the silk shawl hanging from his silver belt and wrap the fruits and vegetables in them to weigh. Kintos were known to be cunning, swift and informal. Such characteristics of Kinto are well shown in Kintouri. The dance is light natured.[4]

Samaia (სამაია)

Samaia is performed by 3 women and, originally, was considered to be a Paganism dance. However, today’s Samaia is a representation of Tamar of Georgia, who reigned in 12th-13th centuries and was the first empress of Georgia. There are only 4 frescos that keep the much-revered image of Empress Tamar. Simon Virsaladze based the costumes of Samaia on the Empress’s clothing on those frescos. In addition, the trinity idea in the dance represents Tamar of Georgia as a young princess, a wise mother and the powerful empress. All these three images are united in one harmonious picture. The simple but soft and graceful movements create an atmosphere of beauty, glory and power that surrounded the Empress’s reign.[5]

Jeirani (ჯეირანი)

The word “jeirani” means gazelle. This dance tells the story of the hunt. It was choreographed by Nino Ramishvili for the Georgian National Ballet. The dance incorporates classical ballet movements and a hunting scene.[6]

Karachokheli (ყარაჩოხელი)

Karachokheli were the ordinary craftsman of Georgia. They typically wore black chokha (traditional men’s wear). They were known for hard work yet a carefree life, as well as a love of Georgian wine and beautiful women, all of which are well represented in the dance.

Davluri (დავლური)

Davluri is also a city dance, but unlike Kintouri and Karachokheli, it portrays the city aristocracy. The dance is similar to Kartuli. However, the movements in Davluri are less complicated and the male/female relationship is less formal. The dance is performed by many couples and with the music and colorful costumes, paints a picture of an aristocratic feast on stage.[7]

Mkhedruli

The word “Mkhedari” means cavalryman. The dance begins in a raging tempo, becoming more and more violent. The legs of the cavalryman imitate the fast movements of the horse, while their body and arm movements impersonate the battle with enemy.

Parikaoba (ფარიკაობა)

A warrior dance from Khevsureti in northeast Georgia. A girl enters, looking for her beloved. He appears only to encounter others, precipitating an energetic battle with sword and shield. When the girl throws down her headdress, the men must stop according to tradition, only to renew their battle soon after.[8]

0 notes

Text

#art#artwork#contemporaryart#digital art#abstracart#nail art#polaroid#positive mental attitude#zoology#2023 art#abstract

0 notes

Text

#art#artwork#contemporaryart#nail art#digital art#polaroid#zoology#abstracart#2023 art#positive mental attitude

0 notes

Text

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

0 notes

Text

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

0 notes

Text

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

0 notes

Text

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

0 notes

Text

“Gela Mikava: An Emerging Contemporary Artist to Watch in 2023, Exploring Alienation and Connection”

#art#artwork#digital art#zoology#contemporaryart#nail art#positive mental attitude#polaroid#environment

0 notes

Text

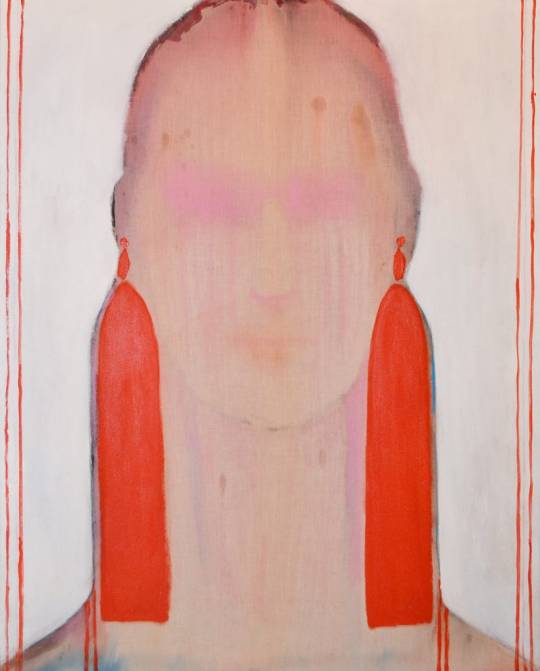

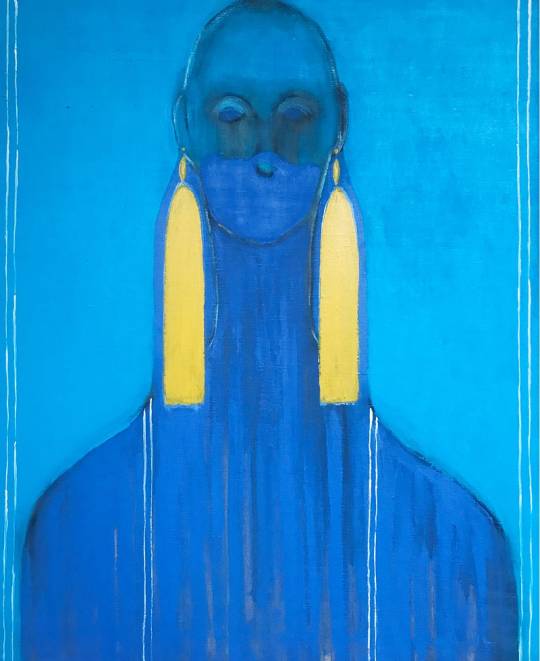

The Bijouterie painting by Gela Mikava

The Bijouterie painting by Gela Mikava

As I stepped into the mesmerizing world of "The Bijouterie" series, created by the visionary artist Mikava, I found myself captivated by the intricate narrative woven within each artwork. The concept of materialism unfolded before my eyes, urging me to embark on a profound introspective journey. The studio exuded an aura of mystery, with scattered jewelry and precious gemstones glistening under the soft studio lights. I could almost feel the weight of society's obsession with wealth and luxury in the air, as if it permeated every brushstroke and pigment on the canvas. As I moved closer to examine the first artwork, I was drawn into a world where desires clashed with reality. The jewelry adorning the figures in the painting seemed to hold them in a captivating trance, their eyes fixed upon the glittering reflection of their material possessions. In their pursuit of wealth, they had become enslaved by the very objects they sought to possess, their true essence obscured by the superficial shine. I could not help but question my own relationship with material possessions. How often had I been enticed by the allure of acquiring things, believing that they would bring happiness and fulfillment? Mikava's art compelled me to reflect on the true value and meaning behind material possessions. Were they a measure of success and self-worth, or were they mere illusions that masked deeper desires? Moving through the gallery, I encountered a painting that portrayed a man surrounded by opulence, his face revealing a blend of delight and discontent. The room, adorned with extravagant decor, seemed to mirror his internal struggle. The paradoxical nature of materialism unfolded before my eyes—a conflict between the ephemeral joy of acquisition and the lingering emptiness that followed. Mikava's artwork skillfully intertwined symbolism and storytelling. The intricate details of each piece mirrored the complexities of our relationship with materialism. Diamonds and gemstones represented society's obsession, their radiant beauty acting as a veil that concealed the pursuit of true meaning and fulfillment. As I immersed myself in "The Bijouterie" series, I couldn't help but reassess my own values and priorities. The series became a catalyst for change within me, prompting me to seek a deeper connection with the world around me and to explore the wealth that lies beyond material possessions. With every stroke of Mikava's brush, I felt a shift in my perspective, an awakening of consciousness. The artworks not only questioned the influence of materialism on our lives but also invited me to ponder the true essence of happiness and fulfillment. They reminded me that the value we place on material possessions is fleeting, while the richness of our experiences, relationships, and personal growth holds the key to a meaningful existence. Leaving the gallery, I carried with me a renewed sense of purpose and an eagerness to embrace a life that transcends the superficial trappings of wealth. "The Bijouterie" series had touched something deep within me, urging me to embark on a journey of self-discovery and to prioritize the pursuit of true value and meaning in my own life. In the end, Mikava's art had become more than just a visual experience—it had sparked a transformation within my soul. It had illuminated the path to a life rich in substance, empathy, and purpose, urging me to resist the seductive allure of materialism and to embrace the beauty that lies beyond the superficial facade of wealth and luxury.

0 notes

Text

The Bijouterie painting by Gela Mikava

As I stepped into the mesmerizing world of "The Bijouterie" series, created by the visionary artist Mikava, I found myself captivated by the intricate narrative woven within each artwork. The concept of materialism unfolded before my eyes, urging me to embark on a profound introspective journey. The studio exuded an aura of mystery, with scattered jewelry and precious gemstones glistening under the soft studio lights. I could almost feel the weight of society's obsession with wealth and luxury in the air, as if it permeated every brushstroke and pigment on the canvas. As I moved closer to examine the first artwork, I was drawn into a world where desires clashed with reality. The jewelry adorning the figures in the painting seemed to hold them in a captivating trance, their eyes fixed upon the glittering reflection of their material possessions. In their pursuit of wealth, they had become enslaved by the very objects they sought to possess, their true essence obscured by the superficial shine. I could not help but question my own relationship with material possessions. How often had I been enticed by the allure of acquiring things, believing that they would bring happiness and fulfillment? Mikava's art compelled me to reflect on the true value and meaning behind material possessions. Were they a measure of success and self-worth, or were they mere illusions that masked deeper desires? Moving through the gallery, I encountered a painting that portrayed a man surrounded by opulence, his face revealing a blend of delight and discontent. The room, adorned with extravagant decor, seemed to mirror his internal struggle. The paradoxical nature of materialism unfolded before my eyes—a conflict between the ephemeral joy of acquisition and the lingering emptiness that followed. Mikava's artwork skillfully intertwined symbolism and storytelling. The intricate details of each piece mirrored the complexities of our relationship with materialism. Diamonds and gemstones represented society's obsession, their radiant beauty acting as a veil that concealed the pursuit of true meaning and fulfillment. As I immersed myself in "The Bijouterie" series, I couldn't help but reassess my own values and priorities. The series became a catalyst for change within me, prompting me to seek a deeper connection with the world around me and to explore the wealth that lies beyond material possessions. With every stroke of Mikava's brush, I felt a shift in my perspective, an awakening of consciousness. The artworks not only questioned the influence of materialism on our lives but also invited me to ponder the true essence of happiness and fulfillment. They reminded me that the value we place on material possessions is fleeting, while the richness of our experiences, relationships, and personal growth holds the key to a meaningful existence. Leaving the gallery, I carried with me a renewed sense of purpose and an eagerness to embrace a life that transcends the superficial trappings of wealth. "The Bijouterie" series had touched something deep within me, urging me to embark on a journey of self-discovery and to prioritize the pursuit of true value and meaning in my own life. In the end, Mikava's art had become more than just a visual experience—it had sparked a transformation within my soul. It had illuminated the path to a life rich in substance, empathy, and purpose, urging me to resist the seductive allure of materialism and to embrace the beauty that lies beyond the superficial facade of wealth and luxury.

0 notes

Text

The Bijouterie painting by Gela Mikava

The Bijouterie painting by Gela Mikava

0 notes

Text

Abstract art has long been a source of inspiration and intrigue. From the vibrant, abstract expressionism of the 20th century to the bold pop-art of the 1950s, abstract art has become a staple of modern culture. That’s why it’s so exciting to introduce the cutting-edge artwork of abstractionist artist Gela Mikava. With Mikava’s collection, you won’t find geometric shapes or representations of real life objects. Instead, you’ll be taken on an immersive journey through a vibrant world of colors and shapes. Using unique styles, textures and materials, Mikava creates vivid, emotionally charged abstract works of art – perfect for any modern space. Blurring the line between contemporary art and abstract expressionism, Gela Mikava creates captivating works of art like nothing you’ve seen before. Be sure to check out Mikava’s online gallery to get a first-hand look into this incredible artist’s world. Discover a truly remarkable collection of abstract artwork, and see what all the excitement is about.

0 notes

Text

Conteporary abstract painting on 2023

Abstract art has long been a source of inspiration and intrigue. From the vibrant, abstract expressionism of the 20th century to the bold pop-art of the 1950s, abstract art has become a staple of modern culture. That’s why it’s so exciting to introduce the cutting-edge artwork of abstractionist artist Gela Mikava. With Mikava’s collection, you won’t find geometric shapes or representations of real life objects. Instead, you’ll be taken on an immersive journey through a vibrant world of colors and shapes. Using unique styles, textures and materials, Mikava creates vivid, emotionally charged abstract works of art – perfect for any modern space. Blurring the line between contemporary art and abstract expressionism, Gela Mikava creates captivating works of art like nothing you’ve seen before. Be sure to check out Mikava’s online gallery to get a first-hand look into this incredible artist’s world. Discover a truly remarkable collection of abstract artwork, and see what all the excitement is about.

0 notes