Link

“It’s one thing, of course, to center a tween or teen of color on the cover, be it a stock photo, a photo commissioned for the book cover, or an illustration. It’s another thing — and something that still stands out quite a bit — to see a wide array of skin tones represented on ensemble casts. Perhaps it’s fair to the book’s content that all of the major characters are white, begging the question of why that choice was made, but perhaps, too, it’s not considering that readers are not all fair and ivory white and perhaps a little differentiation is realistic.“

12 notes

·

View notes

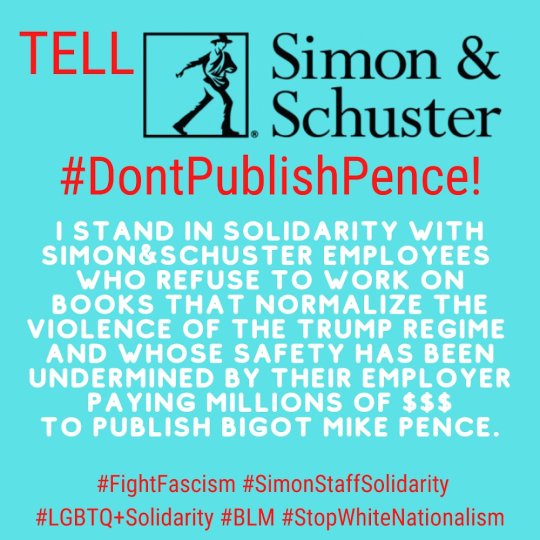

Photo

“I stand in solidarity with Simon & Schuster employees who refuse to work on books that normalize the violence of the T***p regime and whose safety has been underminded by their employer paying millions of $$$ to publish bigot M*ke P*nce.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Queer YA has changed so much in the 10+ years I’ve been reading it — which is a relief. We’re no longer limited to “issue” books, and identities other than gay and lesbian have made their way to mainstream publishing. There are still improvements to be made, but it regularly shocks me what is possible in queer YA now. I remember when it was difficult to find any YA titles with a bisexual main character, so it was a surprise to me when I read three YA titles almost back-to-back that have discussions about bisexuality and biphobia that I’ve never seen in books before.‘

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Here is a radical, potentially dangerous thought: Maybe it’s not that kids and teens of color and other marginalized and minoritized young people don’t like to read. Maybe the real issue is that many adults haven’t thought very much about the racialized mirrors, windows, and doors that are in the books we offer them to read, in the television and movies we invite them to view, and in the fan communities we entice them to play in. ”

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, “The Dark Fantastic.” Apple Books.

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

“’Anti-racism’ is a noun but urgency requires us to treat it as a verb, I say. It means taking your awareness and turning it into action. Into doing something concrete. And then to keep doing it.”

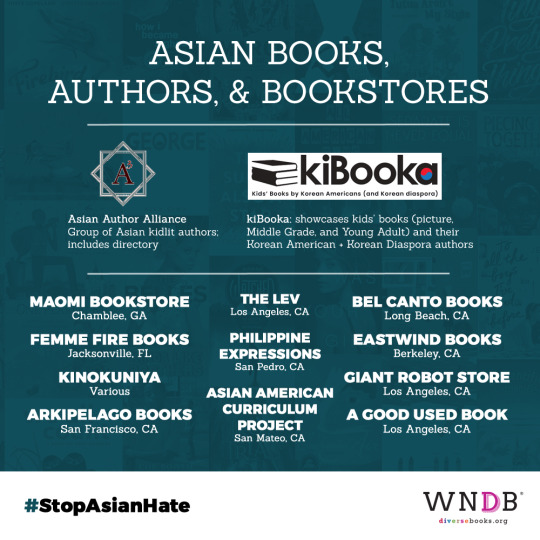

We Need Diverse Books social media manager JoAnn Yao wrote about the Atlanta shooting, growing up Asian in Georgia, & how both solidarity and joy can be found while drawing a cartography of self. See below for our resources on how to take action, stand against anti-Asian racism, and #StopAsianHate.

CW: Mention of Atlanta shooting. Full list of warnings at beginning of essay.

* * *

Asian Books & Authors:

Asian Author Alliance’s Kidlit Directory – “A Directory of Asian Kidlit Authors as a way to help others discover and amplify Asian voices and stories!”

KiBooka – site by author Linda Sue Park that showcases kids’ books (picture, Middle Grade, and Young Adult) and their Korean American + Korean Diaspora authors

Asian-Owned Bookstores:

Maomi Bookstore (Chamblee, GA)

Femme Fire Books (Jacksonville, FL)

Arkipelago Books (San Francisco, CA)

Bel Canto Books (Long Beach, CA)

Eastwind Books (Berkeley, CA)

Giant Robot Store (Los Angeles, CA)

A Good Used Book (Los Angeles, CA)

The Lev (Los Angeles, CA)

Philippine Expressions Bookstore (San Pedro, CA)

Kinokuniya (Various)

The Asian American Curriculum Project (San Mateo, CA) – proceeds from sales also support their nonprofit, which works to “bring a wide variety of Asian American curriculum materials to schools, libraries, and the general public.”

Atlanta-based AAPI Organizations:

Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta – “the first and only nonprofit legal advocacy organization dedicated to protecting the civil rights of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders (AANHPI) in Georgia and the Southeast.”

Center for Pan Asian Community Services – “Established as the first and largest Asian and Pacific Islander health and human service agency in the Southeast region, CPACS has been providing its core groups of services to immigrant and refugee families in Georgia since 1980.”

Fundraisers & Action Items:

Verified Atlanta shooting victim fundraisers

GoFundMe-organized AAPI Community Fund

Asian Americans Advancing Justice in Atlanta Fund for the victims and their families

Anti-Asian Violence Resources – includes statistics, bystander trainings, mental health resources, and more

Asian Americans, A PBS Documentary – “a five-hour film series that delivers a bold, fresh perspective on a history that matters today, more than ever… Told through intimate personal stories, the series will cast a new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played.”

Stop AAPI Hate – nonprofit that tracks incidents of hate and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S.

The Asian American Curriculum Project – “Our mission is to educate the public about the great diversity of the Asian American experience through book distribution, cultural awareness, and educating Asian Americans about their own heritage, thus instilling a sense of pride.”

647 notes

·

View notes

Link

In order to get that broader variety of stories published, Latinx communities need to read the books that already exist for the publishing industry to see that these books are in demand. “If our people are not reading those books, if Latinx teachers are not getting those books in their classrooms, if Latinx librarians are not making sure that Latinx books are in their library, if Latinx booksellers are not making sure those books are prominently displayed in their stores, then we shoot ourselves in the foot,” explained Bowles.

For Lovato, #DignidadLiteraria had the greatest impact on Latinx people themselves. “We ourselves, waking up to the fact that we’ve been abused, ignored, marginalized, insulted by US publishing,” Lovato said. “You have thousands upon thousands of people who had an idea like, ‘Something’s wrong. I don’t see any books about me.’ Suddenly we come together and we realize we’re not alone. Over the long term, that’s the most important thing.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of Audience: Matthew Salesses’ Craft in the Real World

Earlier this year, I devoured Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping by Matthew Salesses. To say it’s the most important book that I’ve read on writing would be an understatement. My copy is already so marked up from this initial read, and I find myself musing over at least one of Salesses’ points daily. Definitely will be revisiting this many, many times.

Craft’s main thesis is that we, as writers and writing educators, have a responsibility to learn about and/or incorporate diverse and inclusive storytelling into our work. Work is a broad term, but reflects both our writing projects and our work as students and teachers. This can be done even if you aren’t part of a marginalized community, simply through education and learning how to avoid obvious or subconscious harm in your work or instruction.

The book is split up into two parts: craft tips and workshop tips for writing programs. For students in these programs, the first part, which focuses on term definition and technique, as well as how to rethink what we’ve been taught in writing classes, could be most beneficial. This book does two great things: it teaches new information, but also answers so many questions, like what to write and how best to do it. It’s a conversation many authors are having now, as a way to make publishing more inclusive.

For example, it’s important to understand how deeply rooted craft is in culture, and how many of the techniques we’re taught are built in a culture of straight, cis, white, able-bodied male writers. Though many have had a sense of this, this book provides insight on recognizing how. There are problems with writing advice like, “You have to know the rules in order to break them;” the “rules” in writing have been historically exclusive of anything outside of Western culture, and often aren’t extended to experiences/rules not set forth by that aforementioned default.

As Salesses explains, many professors and students don’t understand the issues behind this statement. Salesses goes in depth into this argument, as well as tips for other ways of relearning craft, in a way that is both digestible, educational and fascinating.

One of the most crucial things this book discusses, though, has to do with audience. Salesses devotes whole chapters into figuring out who our intended audience is as an author, and how to cater our books to them in a way that is familiar and validating without being harmful. When people claim they “don’t get” a novel, it is often because it was not intended for them. Anybody can read your book, but if you want a particularly impactful/personal one, your book can’t be for everyone.

Salesses explains that workshop critique aimed toward marginalized authors can often be harsher if they are writing about experiences not known to people outside of their culture, as it’s either deemed “not relatable” or “untrue,” among other things. As he states, these critics “only have to recognize the norms they already understand [because that’s what they're used to]” (7).

Salesses is adamant that knowing our intended audience should be a focal point of our work as authors, and an important teaching point for educators: it determines how we identify characters, how we write them, and what to include on the page. It’s key in connecting to a certain group of people, and in understanding our values for our specific project, as well for ourselves. Among his large thesis, a large aspect of craft is knowing who you’re writing to, and why. Its impacts far extend the page, for better or for worse.

0 notes

Link

“Anti-racism work is all too often done as a performance—to be popular and look ‘woke.’ It can be painstakingly ornamental. It needs instead to embed community efforts, organizers, and the actual people who live with America’s oppression. It needs to make structural changes that dismantle centuries-old, racist institutions from the ground up in order to rebuild with a commitment to community, safety (without police), justice, diversity, and actual equity. For equity work to work, it must be handed to the community. We have to actually trust the people we say we want to empower to make structural changes, not just tinker at the edges of injustice.“

290 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Juliet Takes a Breath by Gabby Rivera, Celia Moscote (Illustrations)

A NEW GRAPHIC NOVEL ADAPTATION OF THE BESTSELLING BOOK! Juliet Milagros Palante is leaving the Bronx and headed to Portland, Oregon. She just came out to her family and isn’t sure if her mom will ever speak to her again. But don’t worry, Juliet has something kinda resembling a plan that’ll help her figure out what it means to be Puerto Rican, lesbian and out. See, she’s going to intern with Harlowe Brisbane – her favorite feminist author, someone’s who’s the last work on feminism, self-love and lots of of ther things that will help Juliet find her ever elusive epiphany. There’s just one problem – Harlowe’s white, not from the Bronx and doesn’t have the answers. Okay, maybe that’s more than one problem but Juliet never said it was a perfect plan… Critically-acclaimed writer Gabby Rivera adapts her bestselling novel alongside artist Celia Moscote in an unforgettable queer coming-of-age story exploring race, identity and what it means to be true to your amazing self. even when the rest of the world doesn’t understand.

Review: I read an ARC of Juliet Takes a Breath quite a long time ago, so when I saw that a graphic novel adaptation of it was coming out, I knew I had to check it out. Since it’s been a while, the story was almost completely new to me, and I can safely say that you don’t need to read the original book to read this graphic novel. With all that said, let’s dive in!

Juliet Takes a Breath follows Juliet as she heads to Portland to intern for feminist author Harlow Brisbane. While there, she embarks on her own journey of understanding who she is as a Puerto Rican lesbian, and her own relationship with her family and friends. Like the illustrations, Juliet’s story is one told in bold, bright strokes. It’s poetic, sometimes messy, and always full of meaning. Like the novel, the graphic novel doesn’t shy away from depicting racism, white feminism, homophobia, and so much more.

The art is, as you can tell from the cover, simply gorgeous. It’s brilliant and eyecatching. I’d recommend checking out Juliet Takes a Breath even if you’ve already read the book, just so you can admire the illustrations.

TL;DR: If you’ve already read Juliet Takes a Breath, check out the graphic novel anyway. And if you haven’t, this is one you’ll definitely want to pick up at the library or buy when you get the chance.

Recommendation: Borrow it someday – particularly if you’re looking for a gorgeous graphic novel to pick up!

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

“I make my living off my imagination, but this summer, as I watched Homegoing climb back up the New York Times bestseller list in response to its appearance on anti-racist reading lists, I saw again, with no small amount of bile, that I make my living off the articulation of pain too. My own, my people’s. It is wrenching to know that the occasion for the renewed interest in your work is the murders of black people and the subsequent “listening and learning” of white people. I’d rather not know this feeling of experiencing career highs as you are flooded with a grief so old and worn that it seems unearthed, a fossil of other old and worn griefs.

When an interviewer asks me what it’s like to see Homegoing on the bestseller list again, I say something short and vacuous like “it’s bittersweet”, because the idea of elaborating exhausts and offends me. What I should say is: why are we back here? Why am I being asked questions that James Baldwin answered in the 1960s, that Toni Morrison answered in the 80s? I read Morrison’s The Bluest Eye for the first time when I was a teenager, and it was so crystalline, so beautifully and perfectly formed that it filled me with something close to terror.”

208 notes

·

View notes

Photo

YA Books About Witches/Wizards/Magic Schools and Magic Training featuring LGBTQ+ Characters

Carry On (Simon Snow series)

In Other Lands

Bluebell Hall

The Witch Boy series

Scholars and Sorcery series

Wayward Children series

Supermutant Magic Academy

The Rules series

Tally the Witch (Fatebane series)

Sidekick Squad series

A Hero at the End of the World

Magical Girl Academy series

The Lost Coast

These Witches Don’t Burn/This Coven Won’t Break

Brooklyn Brujas series

Cemetery Boys

Witch Eyes series

The After Life Academy: Valkyrie series

More on this goodreads list!

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

“You opened my eyes when you asked how I could call myself Latino when you, a white person, speaks more Spanish than I do. You are actually way more Latin@ than I am!”

An important read from writer Wyl Villacres in McSweeney’s “Open Letters to People or Entities Who Are Unlikely to Respond” series. This essay paints a clear picture of the whiteness of MFA programs and why we need to not only bring more writers/faculty of color into those programs, but make the framework anti-racist. Though there aren’t explicitly-stated answers within this essay, aside from educate yourself, it offers the question nonetheless.

In conversation with Matthew Salesses’ recent book, Craft In The Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, there’s a need to reconsider what we teach, how we teach it and who we’re teaching it to. The lack of awareness is what perpetuates harmful writing, however “unintentional” it may be.

Marginalized writers are often under more scrutiny than their white peers in the classroom, and listening to their stories, as well as hiring more faculty of color and seeing where white professors and peers can improve, is crucial to make sure that incidents that Villacres describes don’t happen, or at least are acted upon accordingly. We must have these conversations in the classroom, and to hold institutions accountable, as writer Paola Capó-García writes in an article for Remezcla:

“Change has to start with how we cast our institutions. We have to move away from the default image of The Professor: the straight, white, able-bodied male... [the MFA program is] a place to build communities, to find support groups, to read more than you’ve ever read, to access “real world” resources, to take in disciplines you would’ve never encountered by yourself, to genuinely alter people’s way of thinking, to become better educators.”

We must work toward change from the inside, find support and challenge the norm, especially through our own writing. It’s harder than it seems, but these sources are a start in bringing attention to a problem that is known, but rarely faced head-on.

0 notes

Link

Jacqueline Woodson: I remember when I wrote Autobiography of a Family Photo back in the ’90s, it was the White Boy Club: white boys were getting invited to the parties, getting the film contracts, getting the big advances. Publishers were saying, “Well, Black folks don’t buy books.” Out loud. The time has shifted, and that white-boy voice is much quieter—and our voices are amplified. There was one reviewer who asked me when I won the National Book Award, “What does it feel like to win such a big award?” And I was like, “Are you talking about the Coretta Scott King, or are you talking about the NAACP Image Award?” I love being on the New York Times best-seller list, but it means nothing if a Black kid in Brownsville doesn’t know my name.

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

In order for publishing to move forward, publishers must have BIPOC professionals not just in the visible positions, from editors to v-ps, but those working behind the scenes to get books into the hands of readers. “There is also a need to diversify other departments, too, including marketing, publicity, sales, and management,” says Jalissa Corrie, Lee & Low Books’ marketing and publicity manager. “Because people think of authors and editors first when they think of publishing, calls to diversify other levels and areas in publishing can sometimes get lost.”

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

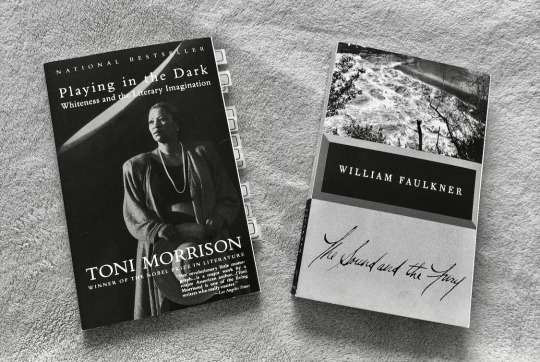

On Literary and Real World Violence: A Response to Morrison, Laymon and Faulkner

I’ve been in school for two weeks now, and literary violence is at the forefront of my mind.

Toni Morrison’s collection of criticism, Playing In The Dark: Whiteness in the Literary Imagination, has been a faithful companion since the beginning of the semester. Morrison is adamant about education. Her eloquence and grace seeps off the pages, defining African Americanism (“an investigation into the ways...a nonwhite, Africanlike (or Aficanist) presence or persona was constructed in the United States'' (6)), its place in Western literature, and the impact of harmful representation. Morrison speaks for those pushed into the role of “The Other” in America, and, consequently, in America’s great novels as well.

Kiese Laymon begins his essay, “I Am A Big Black Man Who Will Never Own A Gun Because I Know I Would Use It,” addressing this idea as well, zeroing in on the personal impact of one of the country’s most treasured writers.

Laymon describes his fascination with William Faulkner, who is often viewed as a father of the literary subgenre, southern gothic. As a teenager, Laymon read all of his novels, and felt that Faulkner was one of the more progressive writers of the early 20th century. Laymon was encouraged by his mother and teachers to strive for work adjacent to his; the writer could essentially “protect [him], ironically, from white men, white men’s power, and all men’s bullets.” However, as Laymon grew up, he saw that despite Faulkner’s intentions, he was tired of “white writers who simply could not see, hear, love, or imagine black folk as part of, or central to, their audience.”

“I Am A Big Black Man Who Will Never Own A Gun Because I Know I Would Use It” was written in between visits to Faulkner’s home in northern Mississippi. Laymon finished a draft on the front porch, taking note of how he could see the house of Callie Barr, the Faulkner family’s help, from his peripheral. Laymon studied the relationship between Faulkner and Barr from a vantage point of nearly a century, documenting his findings in his essay. Barr, who passed away in 1940, left an impression on the novelist, who delivered a heartfelt eulogy at her funeral, speaking of her fidelity to his kin as if she were one of the family. He addressed Barr’s “devotion and love for people she had not borne” straightforwardly.

When reading this, I couldn’t help but think of Dilsey, the Black help in Faulkner’s 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury. Now aware of Barr’s life, I can see the influence of the loyalty that Faulker felt she employed. Dilsey, along with her sons and grandsons, care for the fictional Compson family; particularly the youngest child, Benjy, who is mentally disabled and depends on her well into adulthood. Fidelity to the family comes up frequently, and is extremely problematic. It’s what Laymon later reflects upon, understanding that “black fidelity and devotion to white families that are not our own are a terrifying part of our story in this nation.”

Laymon’s essay is not necessarily a piece of literary criticism. It is a vitally important call to action to end the violence against Black people in our country. He writes of America as a “desperate culture,” where ego and destruction come before the safety and livelihood of our children. For Black, brown, and indigenous children, this complex is a matter of life and death (“...why a nation that parades its big guns thinks it has the moral authority to audaciously tell its children and its black folk what to do with their little guns”). For white children, it is the risk of “moral annihilation;” the fear of being caught, of having an image tainted when they end up making headlines for racist or murderous acts. I think of the Kenosha shooter now, of seeing childhood pictures of him on my Twitter feed, holding an AK-47, with dreams of joining the police force at the forefront of his mind. White children grow up with the comfort of knowing they have the police on their side. They have the ability to own firearms before they are out of grade school. They have the ability to use them to kill, and still sleep in their beds that night.

They have the privilege of returning to their lives; the privilege of another day.

In a piece written shortly after Emmett Till’s death, Faulkner wrote, “If we in America have reached that point in our desperate culture when we must murder children, no matter for what reason or what color, we don’t deserve to survive, and probably won’t.” Laymon criticizes this overly optimistic view; they are words that are still on our minds today, and that still aren’t compensated for. He writes, “Faulkner would have known that you cannot love any child in the United States of America if you refuse to accept that this nation was born of a maniacal commitment to the death, destruction, and suffering of black, brown, and indigenous children...Faulkner would have accepted that there has never been a time in this desperate nation’s history when American grown folk have refused to murder children.”

To make this country a better place for those who come after us—to make it a place that meets basic rights—we have to advocate and fight for those who have been left behind. We have to fight for everyone to have the chance to begin again; to wake up in the morning in their own beds and carry on another day. But, as Layman states, “If we really wanted to make this country less violent, we would tell the truth.” The truth is an accurate representation of marginalized bodies in the art we make. The truth is creating space for those bodies.

Though Faulkner was once a staple of Layman’s education, he is aware of the importance of nothing where gaps lay. Faulkner was still a white man who used derogatory language in his prose, and his Black characters were still representative of a harmful past. He isn’t the only one. I’m reminded of some of America’s most prized pieces of pop culture: Gone With The Wind, Flannery O’Connor’s short stories, amongst countless others. The list is grossly incomplete.

I’m aware there is actual physical violence happening in the world; it is why I am writing this essay instead of being in class. But in the context of Layman’s devotion to exploring a literary past—and as a student studying literature and how to, hopefully, write my own one day—we have to acknowledge the violence that occurs on the page as well. Morrison paints the picture clearly. It occurs within the words actually printed; in the harmful descriptions of those of us viewed as Others. It occurs when the words are forgotten; an erasure that speaks without words.

There is a truth that needs to be told. Layman emphasizes that, “if we bring [it] into every space we enter, every space we long to bring a gun...our children will not be safe, but they will eventually be safer and far less addicted to violence than we are.”

As artists, it is our job to make our work inclusive. I was once a child of words, and am coming into my own as a young adult yearning to weave her truths within them. Literature has been my safe haven since around the time Layman first discovered Faulkner. And, like him, I no longer want to fall victim to the metaphorical gun resting just outside the page.

We have a responsibility to create art that speaks to more than some. We have the ability to help reconstruct what we’ve been taught. The call for creatives in the modern age is to make work that goes against the American concept of violence, for American violence seeps into every aspect of everything we do. It is in our language, our novels, our records.

The question is not whether we can, or have the ability, to begin; it is whether we are willing to do so. Layman proposes an important question: “Do you care enough about the children of this country to begin divesting from all forms of American violence?”

Our silence can sometimes speak just as loud as those firing guns.

Originally written in September 2020.

1 note

·

View note