Text

Kermit the Frog: It’s Not Easy Being a Meme

When Jim Henson created Kermit the Frog in 1955, he surely had no idea that his puppet would go on to become a timeless cultural icon, a celebrity in his own right, and most recently, an internet meme sensation. Yet decades before Reddit and Imgur, Kermit was already the perfect candidate to become all those things. His simple character design has remained virtually unchanged for over 60 years, making him instantly recognizable and easy to edit and remix. His static ping pong ball eyes and relative lack of features make him dependent on body language, props, and captions to express emotions. And he has appeared in hundreds of episodes of The Muppet Show and Sesame Street and starred in dozens of films, so the internet holds a dizzying array of Kermit photos to form the basis of memes. Kermit has competed on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and made the rounds on daytime and late night talk shows with multiple generations of hosts. There is not one, but two Kermit puppets behind glass at the Smithsonian. He is the most interesting frog in the world.

How could he NOT occasionally take over the internet?

According to Google Trends, the most popular Kermit meme is what Know Your Meme calls “But That’s None of My Business.” It typically features Kermit nonchalantly drinking a beverage and calling out questionable behavior or hypocrisy, asserting at the end “but that’s none of my business.” I think it’s meant to play Kermit as a gossipy casual observer, and often a condescending one. Many of these witty social observations originated in black internet subculture and made the rounds in those circles before reaching the internet at large.

There are two main incarnations of But That’s None of My Business: one of Kermit drinking tea in a 2014 Lipton advertisement, and the other of Kermit sipping milk through a straw in the very first episode of The Muppet Show (skip to about four minutes in, you’ll know it when you see it). This trend reached peak popularity in the days following June 20th, 2014, when an Instagram account was created to highlight the best of Kermit’s shade throwing and gained over 130,000 followers.

(I just want to pause here so I can imagine reading the previous sentence to Jim Henson in 1977 and wonder how he’d react to the idea of his character thriving in a bizarre, complex world Henson would never live to see.)

But That’s None of My Business enjoys blue-chip meme status to this day, but was given a brief boost on June 21st, 2016 when Good Morning America infamously tweeted a collage of popular memes and used the hashtag #tealizard to describe Kermit. Tea lizard! Predictably, Twitter lost its collective mind. Mocking of GMA as an out of touch corporate enterprise ensued, as well as the inevitable corrections that frogs are amphibians, not lizards. There was even backlash accusing GMA of whitewashing the Kermit meme by erasing its black comedian origins. In a strange turn of events, the social media coordinator for GMA tried to claim on Twitter that people have actually called this meme Tea Lizard, implicitly casting everyone else as out of touch.

Here’s the great thing about tea lizard, though: a year earlier, in the spring of 2015, scientists announced they discovered a new species of glass frog in Costa Rica that bears a striking resemblance to you-know-who:

Newly discovered frog is a Kermit look-a-like. #StopEverything #StillNewStuffInTheWorld http://t.co/8qZuTYoO3G pic.twitter.com/2e0gt5sIIf

— KariAnn Ramadorai (@KariAnnWrites) April 20, 2015

This does little to rebut the Tea Lizard truthers, and maybe we have to brush aside the fact that the original Kermit actually did look more like a lizard, but I still find it hard to believe that many people would call a fuzzy, toothless, scaleless creature—who again, calls himself a frog—a lizard.

The other famous Kermit meme has been dubbed “Evil Kermit,” and it’s taken from a screenshot of the 2014 film Muppets Most Wanted. It’s a shot of Kermit facing his evil look-alike nemesis Constantine, who is wearing a black Sith robe over his eyes. (I think it really speaks to Kermit's unique design that neither Kermit nor Constantine's face is visible in this photo but it’s still obvious who it is.) The captions always imagine the poster’s inner urges to make poor choices in the form of a two-line dialogue—essentially a version of the angel on one shoulder and the devil on the other. The tweet that started it all was posted on November 6th, 2016, and the meme grew in popularity over the following weeks, even inspiring a Miss Piggy version.

You’ll notice that the popularity bump from But That’s None of My Business has an immediate sharp decline, while the spike from Evil Kermit decreased more slowly. I have a few thoughts as to why. One, leisure time on the internet seems to increase in late December as people have time off work and school (see The Annual Cycle of Netflix Popularity). Around this time, a smaller Kermit meme—a Kermit aftershock, if you will—began to reemerge on Twitter thanks to the large following of the quirky high-concept account @jonnysun.

On December 12th, 2016, @jonnysun tweeted this:

when u give urself a gentle hug evrey night before u go to bed, reassuring urself that no mater wat, the day was yours bc u chose to live it pic.twitter.com/fTH8o5k3h9

— jomny sun (@jonnysun) December 13, 2016

This sad, fuzzy Kermit doll belongs to a 17-year-old girl from Finland named Pinja. In September 2016, she began taking photos of her Kermit in various settings and positions and posting them in a thread of tweets, which garnered attention in certain corners of Twitter. Sad Kermit originated in a tweet from Pinja about how much she missed one of her friends. When Jonny posted his own caption for Sad Kermit, he replied to it with a challenge for his followers to turn Sad Kermit into a ‘wholesome meme,’ meaning to lend it a positive and encouraging caption rather than a snide or sarcastic one. Many people obliged in the following days, and BuzzFeed has kindly curated the highlights.

@jonnysun the chalemge.. can u wholesome the sadest meme in the worlbd, i think.. no

— jomny sun (@jonnysun) December 13, 2016

I mention all this because December 12th also happens to be the point on the graph where the negative slope abruptly becomes less steep. The wholesome meme crusade wasn’t enough to stop the inevitable decline of Evil Kermit mania, but I think it did have an effect in prolonging it. I also believe (or at least I want to) that good natured humor—like the captions for Evil Kermit tend to be—naturally has stronger staying power than the condescension and criticism offered by But That’s None of My Business. Perhaps there is more social incentive to share a meme that lets people laugh at themselves or at life in general than a meme that chastises others, even if it’s also for laughs.

(If that’s true, it would be a fair criticism to point out that the snarkier meme was more popular. But I’ll remind you that trend popularity is based on how frequently Kermit was Googled as a percentage of total searches at the time, and the world got pretty busy searching for non-Kermit related subjects a couple days after November 6th.The election appearing to interfere with unrelated trends may turn out to be relatively common— it showed up at the end of How Google Trends Works too.)

My annotated graph would have you believe Evil Kermit was only 60% as popular at its peak as But That’s None of My Business, but of course it’s a bit more complicated than that. It turns out the spike for Kermit searches in April 2013 had nothing to do with Kermit the Frog, but is instead related to the conviction of abortion provider Kermit Gosnell for murder, manslaughter, and a host of other federal drug crimes related to his abhorrent cesspool of a clinic and his felonious practice of late term and even post-birth abortions. I did NOT see this coming when I set out to write a lighthearted blog about a Muppet and I don’t want it to take over this post. But clearly, using generic terms like “Kermit” to track meme popularity is subject to unintended and confounding interference.

Aside: I can’t fathom that there was a period of time when people named their sons Kermit. But lo and behold, there’s a whole side controversy over whether Kermit the Frog was named after a friend of Jim Henson…though I’ve never heard of anyone by that name born after The Muppet Show aired.

Anyways, I think choosing more specific search terms can shed some light on the popularity of the memes independently of the popularity of the Muppet himself:

trends.embed.renderExploreWidget("TIMESERIES", {"comparisonItem":[{"keyword":"evil kermit","geo":"","time":"today 5-y"},{"keyword":"but thats none of my business","geo":"","time":"today 5-y"},{"keyword":"kermit tea","geo":"","time":"today 5-y"}],"category":0,"property":""}, {"exploreQuery":"q=evil%20kermit,but%20thats%20none%20of%20my%20business,kermit%20tea","guestPath":"https://trends.google.com:443/trends/embed/"});

You can see three spikes we’ve talked about, but this time I’ve included two names for the tea drinking meme. Because every data point is normalized based on the largest spike, I don’t think it’s a bad assumption to compare the sum of the red and orange lines to the blue. In which case, But That’s None of My Business was more like 94% as popular as Evil Kermit. But that’s assuming there are no other aliases for the Evil Kermit Meme. One starts to get the impression Google Trends isn’t the best tool to do thorough mathematical comparisons.

So we’ve covered a case of mistaken identity with a murderer, a ridiculous Twitter gaffe, and a rare species of frog. What’s next?

Guerilla marketing, it turns out. In the midst of a summer of high-profile celebrity split-ups and divorces, Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy released statements on Facebook and Twitter on August 4th, 2015 announcing they were ending their long-term romantic relationship. But— of course—they would continue to work together professionally on their upcoming TV show “The Muppets” on ABC later that fall. This generated headlines in publications like USA Today and The Hollywood Reporter, but also in the style section of The Washington Post and CNN. (Miss Piggy even did a tell-all on Good Morning America just 9 months before they would forget who Kermit is.) Some reactions contained real emotion, as the news was meant to be taken as the end of a celebrity romance that spanned decades. A few weeks later, it was announced that Kermit had found a new girlfriend, a redheaded pig named Denise. All this internet buzz set up the character dynamics for the beginning of the new TV series when it premiered September 22nd, 2015 on ABC. These news articles were a show outside a show about making a show, because sometimes the Muppets just roll three layers deep.

I find it striking that this well-timed marketing stunt generated less than half as much interest in Kermit as the creation of an Instagram account that did nothing but post pictures of Kermit mocking social faux pas. Perhaps internet users saw the drama as the corporate stunt that it was, rolled their eyes, and moved on. Either way, it’s a startling reminder to modern PR executives that no amount of focus testing, brand development, and approved social media language will give them full control over what happens to their intellectual property.

Also striking is the fact that I just referred to Kermit as intellectual property and it probably felt a little odd to think about him in such cold legal terms. It did to me when I first typed it. But it’s true: as of 2004, Kermit the Frog is the property of an international media conglomerate called The Walt Disney Company. And by the way, so is C-3PO, Epic Rap Battles of History, and Good Morning America (which airs on ABC, yet another Disney subsidiary). We try to ignore the faceless corporations behind our beloved fictional characters the way we try not to think about how dirty our belts must get when we buckle them before washing our hands: often successfully, but not always. But the Muppets are different than virtually every other TV and movie character because the media and pop culture in general seem bent on pretending that the Muppets are real people.

Okay, yes, C-3PO, R2-D2, and BB-8 did appear at the Oscars last year and give a shout-out to John Williams. And sure, there is an entire attraction at Disney World premised on the droids being real. And yes, okay, fine, live Stormtroopers march around Disney’s Hollywood Studios. But that’s pretty much the extent of their interaction with the real world, and it’s the same for Disney’s other characters. Mickey and Minnie don’t give interviews to journalists and run official Twitter accounts. They don’t even speak! They interact with the real world by giving kids hugs, autographs, and photo-ops. Adults join in too, one reason being to have fun with their kids, a more cynical reason being the $95per person incentive they paid just for the opportunity. But I suspect most guests - kids included - know it isn’t real but play along anyways because there’s no other place where you can get a big hug from a 7-foot tall Pooh Bear. It’s special not because The Walt Disney Company or grown-ups say it’s real, but because we let it be real.

So it goes for the Muppets, but for some reason, we let them take their reality way farther into ours. It probably has to do with the way they entered the public consciousness through a variety show about making a variety show guest starring real human celebrities decades before wacky meta hijinks became popular. (One surefire way to attract praise and adulation from Hollywood is to affectionately and relentlessly lampoon it.) Audiences became used to seeing the Muppets interact with human stars. Next thing you know, the Muppets are being invited to speak in public and make TV guest appearances of their own. Kermit was evenbeing credited a the author of a best-selling book. The crossovers between Muppet world and the real world became part of their charm. But unlike Mickey, Pooh Bear, Santa Claus, and the Easter Bunny, normal people like you and I can’t go to a theme park or a mall and shake their hands. The Muppets were accessible only to celebrities, which made them celebrities on their own.

Of course, the real reason non-celebrities can’t meet the Muppets in person is because it would be impossible to hide the talented voice actors and puppeteers who bring them to life below the camera, and seeing how the sausage gets made would shatter the layers of pseudo-reality they’ve fabricated for themselves. So rarely are the human performers behind the Muppets recognized for their work. They generally get press only when the story is about the current Muppet production itself rather than the actual Muppets. It has become totally normal for reporters to interview Muppets in character. It’s been argued that this practice makes reporters complicit in providing free advertising for Muppet movies and TV shows under the guise of arts journalism. Is the charade necessary for the Muppets to stay unique and relevant in our postmodern TV world?

I was thinking about the media and the future of the Muppets when just last Sunday, Sesame Workshop introduced Julia, a young Muppet with autism who will join the cast of Sesame Street on April 4th. David Folkenflik’s segment on NPR’s Morning Edition and Lesley Stahl’s segment on 60 Minutes include brief scenes where they talk to Abby Cadabby, Big Bird, and Elmo in character. Neither of them really needed to do this for their stories to work, but there’s something irresistibly charming about getting to interview Muppets. In NPR’s segment in particular, the in-character exchange with Abby set up how the Muppets describe Julia and her condition before Folkenflik moved on to the substance: interviewing the actors and showrunners at Sesame Workshop. With a format allowing for extended segments, 60 Minutes went more in-depth about how Sesame Street began as an experiment in educational television for children and how they continue their mission today. The Sesame Workshop conducts extensive research and consultation with educators and child psychologists to develop their characters and programming. They reached out to 14 autism advocacy groups for input into how to best portray the condition, and published books and digital content featuring Julia before bringing her onto Sesame Street. The Workshop hopes to familiarize non-autistic children with the kinds of behaviors autistic children commonly exhibit. And by showing how Julia fits into her group of Muppet friends, they hope to send the message that autistic kids can fit into their friend groups too. This is the latest of many difficult social situations Sesame Street has tackled to help today’s children better understand the world and treat others with respect. They’ve introduced children to wheelchairs, skin color, incarceration, and even death. As long as Sesame Workshop continues to pioneer new ways to make our increasingly complex world understandable to children, I believe Muppets will have no problem staying relevant. (The real question is whether or not local PBS stations will continue receiving federal subsidies to broadcast it, and for that, you’ll have to ask Ronald Grump…I mean…you know who I mean.)

The Muppets of the movies are like the rude older siblings of the Sesame Street Muppets. Their mission is entertainment, not non-profit children’s education. Obviously, nostalgia lends a lot of power to the Muppets, which is one reason why the 2015 TV series was marketed towards adult audiences and dealt with less than family-friendly themes.

I don’t know if the rude older sibling Muppets will forever hold the respect of the public simply because they’ve endured the test of time, regardless of what they have to offer today.

But I do know this: if I saw Joy and Sadness from Inside Out at Disney World, I wouldn’t hesitate for a second to get my photo taken with them. To be honest, I think I’d be a little starstruck. I literally keep a Sadness plush doll on my bookshelf to remind me how much the message of that movie resonated with me. I’ve spent an unreasonable amount of time thinking about Inside Out, and it’s made me invested in the characters to the point where if I were offered the opportunity to simply pretend to meet them, I’d have no reason not to, regardless how silly it is. Maybe some people have a similar bond with the Muppets. Maybe this country has that kind of a bond with the Muppets, so our culture gives them attention whenever they have something to say. If we're really so invested in our relationship with them, maybe we have no reason not to as well. because we’re invested and have no reason not to. The Muppets make their share of problematic (and dare I say unfunny) jokes. But their timeless, cornball humor gave them a place in our culture long enough for them to become a fixture and even make fun of themselves along the way.

Iconic, self-aware, and eager to self-parody?

Kermit didn’t need the internet to become a meme.

0 notes

Text

At Least 2016 Was A Good Year For Sports

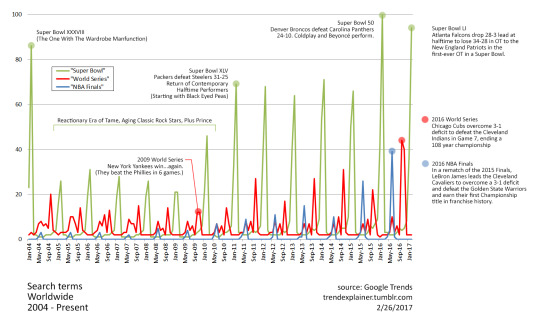

2016 was apparently the best time for postseason sports in the last 14 years, at least according to Google. The 2016 World Series, NBA Finals, and Super Bowl all generated the highest Search Interest since Google started collecting Trends data in 2004. (I would have included results for the Stanley Cup Finals, but they barely register as a blip compared to the NFL, MLB, and NBA championships.) This year’s Super Bowl LI scored closely behind 2016′s as the second-most popular Super Bowl.

Of course, what Super Bowl LI and the 2016 World Series and NBA Finals have in common are unbelievable and unprecedented comebacks. The Cavaliers coming back from a 3-1 deficit to beat the Warriors in Game 7. The Cubs coming back from a 3-1 deficit to beat the Indians in Game 7. The Patriots coming back from a 28-3 deficit to beat the Falcons in OT. (And you can mentally insert your own presidential election analogy right here in this parenthetical. I’ll wait.)

What’s mysterious to me is why Super Bowl 50 (wisely not branded “Super Bowl L”) generated more relative buzz than the Patriots’ shocking OT victory or Janet Jackson’s wardrobe malfunction. Both of those were HUGE stories not just for football fans but in American culture at large. I’m really struggling to find reasons here:

It was the final game of Peyton Manning’s career

It was, by one specific metric, the most watched event in history

Beyonce and Coldplay’s performance just merited a lot of comment?

I think it’s safe to say halftime show buzz does a lot to drive interest in the Super Bowl. The six least searched Super Bowls were the six years following the Janet Jackson incident when tame, aging, and fully clothed male classic rockers like Paul McCartney and Bruce Springsteen performed. (And for the record, I actually enjoyed most of those shows! Those year coincided with my development as a music fan, and all the music I love now stems from enjoying bands like The Who (who performed in 2010) and The Beatles.)

But it can’t all be because of the shows. I’m again left wondering if Peyton Manning should be credited with the huge jump from 2009 to 2010, as it was his Indianapolis Colts who lost that year 31-17 to the New Orleans Saints. And I’m not sure if The Black Eyed Peas ushering (pun intended) contemporary pop back into the Super Bowl should get credit for the interest bump in 2011, or if that’s just due to two fairly popular teams facing off (the Packers and the Steelers) in what turned out to be a close game (the Packers won 31-25). I’d also bet LeBron James had a lot to do with the recent sudden interest in the NBA Finals.

Surely the high interest in the 2016 World Series was because the Cubs and Indians held the two longest championship droughts in baseball and history would be made regardless of the outcome. And if you check the record for recent years, series that require all seven games naturally generate more interest.

0 notes

Text

The Annual Cycle of Netflix Popularity

Disclaimer: I’m assuming here that searches for “netflix” are highly indicative of when people are actually watching Netflix, as opposed to, say, reading news about it. This implies that it’s extremely common to Google “netflix” to get to netflix.com rather then actually typing “netflix.com” in the address bar in a browser. I totally buy this- at least anecdotally- because it’s also extremely common to first Google “google” before you start searching what you were really looking for. Which, I must add, is very silly.

I think it’s totally appropriate that searches for Netflix reach their annual peak the week of Christmas and New Year’s. People are off work and stuck inside with their families. It’s the perfect opportunity to binge through the latest season of whatever you didn’t have time to watch last spring or, you know, watch all of Breaking Bad if you haven’t seen it already.

But then I looked closer and saw that there’s consistently a smaller peak that coincides with Easter Weekend. I bet the peak exists because the main elements of the Christmas surge are still there: consecutive days off work due to a holiday plus families home together. But it’s a smaller peak because the weather is nicer and the break is shorter.

Most interesting to me is the fact that the lowest Netflix popularity for the year consistently occurs at the beginning of May. One explanation I had was May Sweeps. People may be watching season finales on actual broadcast television rather than watching older episodes on Netflix. But May Sweeps occurs later in the month, and there’s a sudden sharp increase after the first week of May, which kind of dashes this idea.

So here’s my hypothesis: the first week of May is end-of-semester crunch time at American colleges and universities. This small, short-lived, but noticeable drop is Netflix viewership primarily caused by college students freaking out about term papers, projects, and finals. And the sharp increase afterwards represents a sigh of relief and relaxation as their focus returns to Parks and Rec.

0 notes

Text

The Burr-Hamilton Duel, Or, Modern Political Feuds Just Aren’t As Dramatic Anymore

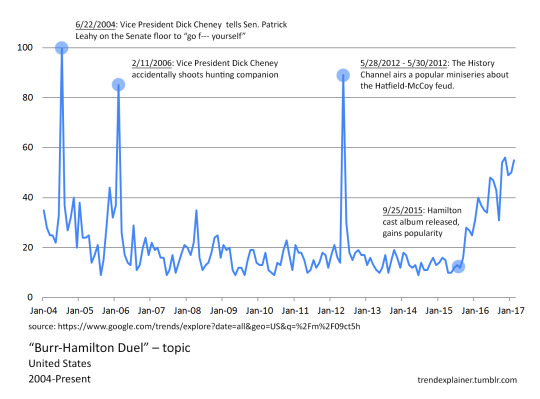

In July 1804, Vice President of the United States Aaron Burr shot and killed former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel, cutting Hamilton’s life tragically short at age 47 but setting the bar incredibly high for the title of “Most Batshit Crazy Feud in U.S. Politics.” Until Hamilton’s incredible life story was brought to the cultural forefront by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash hit musical, this infamous incident lurked in relative obscurity in the back of many American minds. I suspect it was thought about in these three circumstances exclusively:

It came up in U.S. History class (I wish it had in mine!)

The manner of Hamilton’s death was the subject of a trivia question

The sitting Vice President did something patently outrageous and the media needed an incident for comparison

Google lacks data on pre-2004 American thinking, so I’m assuming Burr’s bloody legacy was remembered exclusively by teachers, Trivial Pursuit, and Jeopardy until we had the late-night talk show host’s dream that was Vice President Dick Cheney.

On June 22nd, 2004, Vice President Cheney appeared for a photo session on the Senate Floor and conversed with Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont. The conversation turned heated (Sen. Leahy accused Cheney of cronyism) and Cheney ended it by telling Sen. Leahy to “f— off” or “go f— yourself.” Naturally, the news media found dozens of creative ways to report what was said without actually saying it, with the better articles mentioning the delightful irony that this colorful exchange occurred the same day the Senate passed a bill with 99 votes to increase penalties for broadcasting obscenities on radio and television. And what did President of the Senate Cheney have to say for himself later that week? “I felt better after I’d done it.”

The second Cheney debacle involved lead bullets instead of verbal ones: on February 11th, 2006, Mr. Cheney accidentally shot 78-year-old lawyer Harry Whittington while quail hunting in South Texas. Actually, that’s a rhetorical half-truth; Mr. Whittington’s face and side were caught by the spray of shotgun pellets, not bullets per-se. In Cheney’s defense, he is an experienced hunter who frequently attends outings like these, and Whittington, an amateur, caught Cheney by surprise by being in the wrong place at the wrong instant. Quailgate would dog Cheney’s reputation even into the Obama administration, making him an easy target for late-night monologues. (You could say he made for an easier target than a quail.) After he was discharged from the hospital, Whittington apologized to Cheney for the trouble.

None of the archived stories from major news outlets (namely the Washington Post, the NY Times, and CNN) explicitly mentioned the Burr-Hamilton Duel in their reporting of either incident. But Jon Stewart (and I assume many pundits and anchors looking to fill time on cable news channels) correctly pointed out that the last man to be shot by a sitting Vice President was Alexander Hamilton some 202 years prior. I should point out that Andrew Jackson, who was known for his hotheadedness, became the only U.S. President to have killed a man in a duel in May of 1806 when he shot Charles Dickinson, though at the time Jackson was not a Senator nor the President.

As far as the title of “Most Batshit Crazy Feud in U.S. Politics” is concerned, I’m torn between Burr and the beating of Senator Charles Sumner by Rep. Preston Brooks with a cane on the Senate floor in 1856. The nature of Burr and Hamilton’s disagreements twisted and turned throughout their political careers, becoming intensely personal and ultimately proving fatal. The Sumner incident arose out of political tensions that would later split the nation in two, but though horrific, did not claim the man’s life. I’ll leave it to you to pick the craziest.

The relationship between the F-bomb incident and the Burr-Hamilton duel seems a bit more spurious to me, but surely it was played as a much bigger deal in 2004 then it would be today, especially in light of the language heard throughout the 2016 presidential election. The U.S. Senate is often regarded as one of the most exclusive legislative bodies in the world, and its members are (usually) known to treat one another with professionalism and respect in spite of any deep political disagreements. In fact, this expectation is codified into Senate Rules, as we all recently learned during debate over the confirmation hearing of Senator Jeff Sessions (R-AL) for Attorney General. Senate Rule XIX was invoked by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) to stop Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) from reading a strongly-worded letter written by Coretta Scott King in 1986 in opposition to Sessions’ nomination for a federal judge position.

In the undoubtedly less polarized political climate of 2004, I’d imagine Cheney’s “frank exchange of views” was easily sensationalized: “Such language! On the Senate floor, of all places!” I think the expectation of subdued, genteel behavior in the Senate chamber contributed to the shock and scandal around Cheney, which would in turn lead people to go searching for historical precedent.

Senate Rule XIX, by the way, was created in response to a fistfight on the Senate Floor in 1902. One starts to get the impression that even the wildest "imputing” in Washington these days is pretty tame stuff.

Finding an explanation for that third spike of searches for the Burr-Hamilton Duel between May 28th and May 30th in 2012 was tricky, and to be honest what I have is at best a guess. But here it is: those dates correspond with the airing of a highly rated 3-night miniseries about the Hatfield-McCoy feud on the History Channel. I haven’t seen this miniseries (I have a good alibi though: I was fast asleep at a Franciscan convent at the base of Mt. Kilimanjaro all three nights it aired) so I couldn’t tell you if it or any other programming on American television explicitly referenced Hamilton or Burr at the time. But I’m sure coverage in the press, like this preview in Cleveland, compared the dramatic postbellum clashes between the two Appalachian families to the life-long conflict between Hamilton’s family and Aaron Burr.

It appears at all three of these moments, an anomalously large number of people were presented with the facts and thought, “wait…really?” But the release of the Hamilton cast album in September of 2015 was different. Unlike a one-time political scandal or a television event, it gradually became a cultural phenomenon and pushed social consciousness of this story along with it. I consider myself among the many Hamil-heads who were bit by the history bug and wanted needed to learn more.

So compelling is the Burr-Hamilton story that Search Interest hasn’t dipped below 25 since the beginning of 2016, suggesting that this story couldn’t remain obscure if only somebody (besides Alex Trebek) would tell it well.

And how, Lin-Manuel Miranda. And how.

0 notes

Text

How Google Trends Works

Google Trends presents search data in a fairly intuitive manner, but its simple presentation and use of vague terms like “Search Interest” can easily be misunderstood or misinterpreted. Though I’ll try to stay out of the mathematical weeds in this blog, it’s important to understand what Google Trends is and does, and by extension, what it isn’t and doesn’t do.

If you disagree or just don’t care, feel free to skip this one: this post is mostly for reference.

I want to start by referring you to three direct sources on how Trends works:

Google News Lab Lesson on Data Journalism and Trends

Medium article by Google Data Editor Simon Rogers

Google Trends Help Center

The News Lab lessons provide an excellent and concise overview of almost everything I’m going to cover here, and the Medium article goes in depth on how Trends can be used to compare the popularity of different topics in different regions. There’s a lot of good information out there, but *spoilers* there are also a lot of people who are wrong on the internet, so I want to spell out all the information I trust in one place, in my own voice.

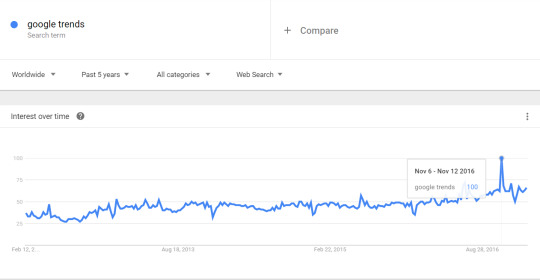

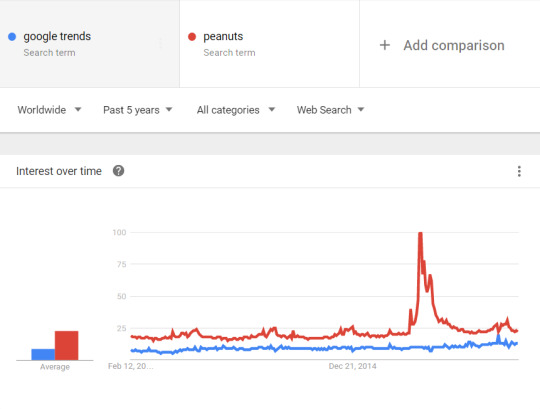

So Google Trends makes graphs like this one:

(Yes, I made my example search term “google trends” so I’m not tempted to get meta later.)

It plots the popularity of a search term on the vertical axis against time on the x axis, assigning a Search Interest score between 0-100 for each time step (for example, between Nov 6-Nov 12 2016). It’s intuitive enough to understand what graphs like these mean, but there are some behind-the-scenes subtleties that warrant explanation, and it’s useful to understand how exactly these graphs are generated.

Trends uses a sample of Google’s unfathomably massive database of what people search as its basis. Actually, there are two separate data samples, and they’re called “Archive” and “Real Time” on their database. The Archive data includes searches made from as far back as January 2004 and as recently as about 36 hours ago. There is one data point for each week in the Archive set. The Real Time data is pretty much current up to the moment you search and includes data points dating only a week into the past, sampled on a minute-by-minute or hourly basis depending on the time range.

Google doesn’t specify how many searches are in the sample. But remember, we’re talking about numbers in the trillions here: even a tiny fraction of a percent is still unbelievably large, so I’ll take their word that this is an unbiased and representative sample of all searches.

What’s Excluded From The Samples?

• Personal information of the searcher is excluded from the sample, but the date and location of the search is retained so trends can be analyzed at different time periods and regions.

• Very uncommon search terms will not turn up any results on Google Trends. This is mostly because they wouldn’t be well-represented in the sample set and the resulting data would be meaningless. But I also suspect most people’s names fall under this category, and it could be easy to track a person down to a metropolitan area or subregion if this data were publicly available.

• Searches with apostrophes and special characters

A note from Google’s Support page: “no misspellings, spelling variations, synonyms, plural or singular versions of your terms are included.” And they left out the Oxford Comma on that one, not me.

Another important note: Trends makes a distinction between terms and topics. If you search Trends for a term, the results will include Google searches that use any of the words in your query. Google’s example is that if you search the term “banana,” you’re also tracking searches for “banana sandwich.” And if you search “banana sandwich,” you also include results for “banana for lunch” and even “peanut butter sandwich.” Topics also group together similar terms, but do so more broadly and in different languages rather than by the words in your query. To use Google’s example again, if you search Trends for London as a topic, your graph will account for searches like “capital of the UK” and “Londres,” which is London in Spanish. Unfortunately, the specific terms that comprise a particular topic is just one of those behind-the-curtain things we don’t get to know about.

How Does Google Normalize The Data?

Google Trends defines Search Interest as the proportion of searches made for a term or topic relative to the total number of searches made overall. (A reminder: for both of these numbers, I’m referring to the searches from the Archive or Real Time data, not the trillions of Google searches made annually.) It’s important to understand that Google Trends does not track changes in search volume. Obviously with the current ubiquity of smartphones and tablets, the volume or raw number of searches made on the average day in 2017 is several times larger than it was back in 2004. Increases in search volume do not necessarily indicate a term or topic is “trending” or becoming more popular, especially over long periods of time where the increase is probably best explained by the fact that Google simply acquired more users and market share.

Trends also will consider Search Interest for a given time range and region of the world. By default, Trends chooses Worldwide in the past five years. If you were to change it to, for example, searches from the United States since 2004, it will redo the math based on the number of searches done in that time range and country and generate a new plot.

Google Trends does this Search Interest calculation for all the time steps (a month, week, hour, or minute) within the specified time range and scales the data into values ranging from 0-100. This is called normalizing the data, and in this case, it’s done by dividing every data point by the maximum value and multiplying by 100. This scales the data so that the maximum value is always 100.

Now that the data is normalized, you can think of all the values relative to the peak. A value of 50 means the term/topic was half as popular as the peak, a value of 20 would be five times less popular than the peak, and a value of 0 means the topic was more than 100 times more popular at its peak.

Remember- popularity doesn’t indicate the term or topic was searched twice, five, or a hundred times as often as it was at the peak. It means that the proportion of searches is that many times less than the peak. This means that it’s theoretically possible for the search volume to increase, but the Search Interest to decrease due to a increase in searches for other topics.

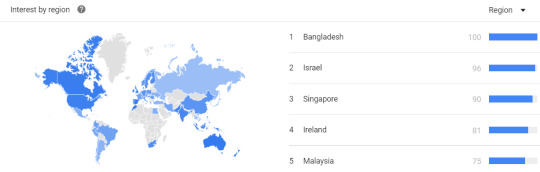

Interest By Region

Trends does a similar calculation to assess the popularity of a term or topic in different countries, states, cities, or metropolitan regions. It looks at the proportion of searches for a term or topic within a region relative to all the searches done within that region. Here are the top regional results of the “google trends” example from earlier:

In this case, Bangladesh had the largest proportion of searches for “google trends” out of all the searches made within that country. Malaysia’s proportion of searches was 75% as large. Remember, we’re using proportions so we can compare the popularity of terms and topics despite large population and search volume differences between regions.

Comparing Trends

You can add terms and topics to your graphs to compare their popularity:

Trends will renormalize the Search Interest values, setting the highest peak out of all the terms at 100 and scaling everything accordingly. This can put spikes into perspective: at its most popular, “google trends” was still less popular than “peanuts.” But notice how the sharp decrease in the popularity of “peanuts” coincides with the sudden increase in “google trends.” This happens to be the week Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, which undoubtedly led to a surge of frantic Googling about topics other than peanuts, decreasing their relative popularity.

You may be wondering…why were peanuts so insanely popular at the beginning of November 2015? Simple: that’s when the Peanuts Movie debuted in theatres! If you were looking for results for peanuts the food without interference from Peanuts the Charles Schultz characters, you have that option too:

Alternatively, you can search for “peanut” rather than “peanuts,” because Trends does not group together results for plural spelling.

0 notes

Text

Introduction

If you want to know something, you ask Google. It's what you do. It happens about 1.2 trillion times a year, or about 59,000 times a second. Never before in human history has it been so easy to find the exact information you’re looking for. And on the flip side, it's never been easier to see what humans are thinking about in broad, sweeping numbers.

I'm referring, of course, to Google Trends, the endlessly fascinating data visualization tool that indexes and tracks the popularity of Google search terms.

The desire to find knowledge is quintessentially human, and as the tool used to fulfill such desires at an unprecedented scale, I think Google Trends can be the basis for fascinating, revelatory observations about human nature and cultures. Though Google Trends is truly a measure of only one thing- what people search on Google- a little historical context, interpretation, and yes, speculation, can go a long way in connecting together various pieces of the human story in new and unexpected ways.

Or perhaps in ways expected but unnoticed.

Or perhaps in ways totally trivial but fun nevertheless.

0 notes