Text

Notes from the Daytona 500

I leave my house in Gainesville, Florida, at six a.m. with a pot cookie and a bar of Klonopin and drive toward the coast to cover the Daytona 500 for a trashy celebrity rag. Since the magazine doesn’t care about the actual race as much as what kind of jeans the celebrities in attendance are wearing, I must arrive early before the action starts. After two hours, I hit Richard Petty Road, which leads me to the race grounds and the press parking lot. I meet a man there who will show me around for the rest of the day. He is very nice and very helpful. I have already eaten the cookie.

The nice and helpful man whisks me to a special tent that I’m not technically allowed inside, but he drops the name of my magazine to the doorwoman, and they have a whispered conversation where I hear the name Juan Pablo repeated several times, and they let me in. I surreptitiously Google Juan Pablo and learn that he is the current star of The Bachelor, a television show where a hunk of meat is paraded before a group of women and told to fall in love. As we enter, the nice and helpful man tells me that the tent is reserved for celebrities like Juan Pablo, and also for a buzzing crowd of Fortune 500 CEOs. What he doesn’t say, but what becomes obvious in a little while, is that corporate money drives NASCAR. And these corporate bigwigs really seem to care about the race, since they get to advertise directly on the car and the driver. In return, the Daytona 500 offers them this tent with fake grass on the floor, and white picnic tables, and immaculately clad servers walking around with trays of single waffle sticks resting in cups of maple syrup. A sound system pumps Cee-Lo’s “Fuck You,” and a dance remix of “Call Me Maybe,” and “Girl” by Beck. The whole thing seems so not NASCAR. It’s just a bunch of rich, old white men milling around with gorgeous young paramours who flash hard eyes, and it’s clear that these people belong to an elite echelon, and they know it, and they are not interested in anyone who is not in that echelon. Judging by how they look at me, they can instantly smell one of their own--and more to the point, they can sniff out someone who doesn’t belong.

The very nice and helpful man steers me across the floor to Juan Pablo’s handler, who asks if I’d like to meet him. I tell her a lie and sit across from him with my pen and pad ready. In the nicest possible way, he refuses to talk to me. He produces a cell phone from his pocket and shows me a picture of a celebrity rag, my celebrity rag, with a headline that says, “The Bachelor’s Ex Tells All,” and then he shows me another picture of him sitting next to his ex, who is holding the same headline, both of them looking disgusted. “Do you see?” he asks, and I do see. Juan Pablo apologizes, and he is very nice, and he is very polite, and I don’t know how to explain that I also think it’s terrible the way they treat him, and that I would love to talk to him about what it’s like being a normal guy suddenly thrust into this vicious scene, and about why he’d agree to appear on a show like The Bachelor in the first place, but as far as treating him like an actual star whose opinions are newsworthy, well, I would need stronger drugs.

A similar thing happens with Nina Dobrev. Her handler tells me she isn’t entertaining the press today. I have no problem with that. I’ve struck out twice, but at least I got close enough to both of them to see their outfits, and that’s all I really need to satisfy the celebrity rag. The very nice and helpful man tells me I’ll have other opportunities--50 Cent will show up later, for example--and he begins introducing me around very politely to people he recognizes, corporate types mostly. These people are all very nice and charming in a disarming and genuine way, since they’re all here to get something out of this event. They all say the same thing: “I love your magazine! I read it all the time!” and though I know they’re all working an angle, I truly believe in their sincerity. It’s nice of them to say, honestly, so I don’t tell them that I just freelance for the magazine because it pays pretty well in an industry where good paychecks are like dinosaurs after the meteor. Instead, I watch these expert hucksters work the room, and I begin to understand the power of schmoozing. I also realize that when the schmoozers ask where you’re from, don’t say Gainesville, Florida, because their faces will drop, their eyes will cloud over, and they will check out of the conversation. You aren’t anywhere important. You can’t help them. Or maybe that’s just what I think is happening. I start to tell them that I spend part of the year in New York, which is a lie, but I will be moving there next year, so it’s kind of true. But, the thing is, these people remain very nice even after I think they’ve checked out of the conversation, and I don’t know why I am lying to them, and it makes me feel worse that some innate insecurity makes me need to lie so I can seem important to people who have only been nice to me, and who I need no favors from anyway. I am very confused morally, and the weed is taking hold.

After the introductions, I settle into a plush leather chair, gobble the Klonopin, and survey the room. The CEOs seem normal, and because no one recognizes them by face, they can hang out unmolested. The celebrities, on the other hand, exist inside bubbles and seem like caged animals. These bubbles are made of handlers, and bodyguards, and hangers on, and I get the sense that they are mirrored on the inside so the celebrities can remain devoted to their brands, their careers, themselves, without having to truly come to terms with how ultimately insignificant human life is. And in their defense, the bubbles offer them protection, which they need, because the press room, where I go next, swarms with a horde of leeches watching their every move, desperate to turn the slightest nothing into a story. And that horde never stops clawing for the latest scoop that will sell magazines. How could you not hide in a bubble? I’d make the same choice. You would too.

After a few minutes on the leather chair, the very nice and helpful man steers me to a press conference, where Chris Evans, Aloe Blacc, Luke Bryan, and Gary Sinise come into the room one by one. They each take a turn sitting alone on a stage facing a crowd of flabby beta males who shout pointless questions at them, and maybe these reporters, these flabby betas, are just normal people trying to pay mortgages and support families, but the way they fawn and grovel like deformed gremlins kneeling before a mighty conquistador is upsetting. And I grovel too, but I think it’s for different reasons. Mostly, I am too polite to say what I really think, so I pretend to grovel, and that might make me more of an asshole, as I gag while participating in the lobbing of mindless questions like so many slow-pitch softballs. Once the questions are over, photographers gather like lampreys to a shark, their shapeless bodies jostling for position while their snapping lenses search for a piece of flesh to capture. It is a gruesome scene, and you can’t help but feel that if the Earth opened and swallowed us all right there, no one’s life would be much worse for it.

Despite the inanity and triviality of it all, however, the celebrity rag wields enormous power. Even though the magazine I’m working for has never provided a single piece of information that anyone needed, I’ve never been treated so well as a reporter. That could be because NASCAR is about as cool as the Republican Party, and it is desperate for Hollywood endorsement in the hopes that some cool might rub off. (That’s a shame, too, because it really is an incredible sport once you get down there near the track and watch the cars scream by like a fleet of bloodthirsty Tyrannosaurs.) But it might also be because the sport still stinks of the Confederacy in a nation that is increasingly non-white. Whatever the reason, I am treated like a king here. As a reporter, I”m used to situations where I have to bother someone until I get what I want. I’m used to people trying to keep me out of important places, while I try to find a way in. I am not used to the way the very nice and helpful man walks me right up to the celebrities, pushes me to the front of every line, and lets me stand on chairs to get a better view.

And to be honest, there is a sort of twisted thrill that comes from having the power of the celebrity rag behind me. I have a lanyard that lets me walk straight past the fenced-in commoners waiting like cattle, red-faced and sweating in the oppressive Florida heat. I waltz right by the Port-O-Let, where a mob of smelly people waits to defecate into a plastic pit that festers in the sun, and by the terrible food tents where an interminable line waits for Bojangles chicken. With the very nice and helpful man at my side and the lanyard around my neck, I go to the VIP tent, piss in a bathroom that is nicer than my house, and eat slow-cooked beef ribs glazed twice with a cherry-habanera barbecue sauce, and Mexican street corn--grilled, then brushed with a mixture of mayonnaise, yogurt, and lime juice, and rolled in cotija cheese, cumin, and other spices. Then I go to a bar and select from half a dozen flavors of fancy fruit juices served in tiny plastic cups, and I take whatever I want without paying a cent. If this were actual journalism, every bit of it would be unethical. But the celebrity press plays by different rules. All I have to do here is provide a report on what the rich and famous do, say, and wear. Swag from NASCAR cannot possibly sway my work.

There’s a thrill that comes with the swag too, and maybe this thrill is what wealth and celebrity are all about. It is a sense of importance, a belief that because you are given these things, you deserve them. And how could the celebrities and CEOs not feel that way? We treat them like demigods. We give them presents they don’t need--Gary Sinise got a red electric guitar--and ask them leading question about how great they are. And why do we do this? Because they’re good at singing? Because they were okay in a few movies? Because they’re on a TV show that will be forgotten by the end of this sentence? It must do something unhealthy to them, and to us as well, but I can’t help feeling that there’s no reason to blame them. They’re just people who worked hard and got lucky; we are the ones treating them like Augustus Caesar.

The race begins as an afterthought, and a Florida thunderstorm comes immediately. The whole thing gets delayed for six hours, and I leave because I have what I need for my story, even though none of it is worth a damn. I am exhausted, and I can’t shake the feeling while driving home through the storm that we are sick, all of us. The way we treat the rich and famous must come from a deep well of mental illness, lousy priorities, and lizard-brain, god-worshipping instincts, and I have helped this hideous machine churn on. When I get home and begin to write my piece, my limbic system reels, not because I think I’m some great writer and this is below me, but because I know that it profoundly does not matter. It does not matter which celebrity arrived when, and whom they were with, and what they wore, and how close they stood to who, and how many selfies they took. No one needs this information. Ever.

And what’s truly sad is that the Daytona 500 is a freakout beyond belief--imagine the Super Bowl, and a country jamboree, and Woodstock put together. You don’t realize on TV how loud those cars are, how fast they go, how massive the track is. You don’t realize that the turns are pitched at such an angle that you can barely walk up them, and if you’re wearing flat-soled shoes, you will slip and the very nice and helpful man will have to hold onto your elbow like you’re a little old lady crossing the street. You don’t realize that they let the fans walk around the track before the race--thousands of them sitting on the infield, signing their names on the starting line, taking pictures of the cars parked in pit road--and that while the fans walk around, so do the world-famous drivers, just like that, elbowing their way past fat guys with cameras and pasty women with sunburns. What other sport allows that kind of access? Television also omits the carnival-like pageantry--the concerts on little stages dotting the outskirts of the track, the food tents billowing aromatic, oily smoke, the rows of RVs and buses with campers grilling in groups and getting drunk in the sun. There is a truly great story at this race. Hell, there are hundreds of them. And the celebrity press will miss them all.

I later learn that Dale Earnhardt Jr. won the race on the same track where thirteen years ago his father died in a grisly car wreck. Not only that, he did it on the night when another driver handled the legendary #3 car for the first time in competition since Earnhardt’s death. I know that my celebrity rag won’t publish that even if I write it. A man vanquishing the race that killed his father, next to the ghost of his father’s car? That isn’t a story to them.

But maybe, just maybe, Juan Pablo will find true love.

0 notes

Text

Impeachment Protest: Melbourne, Florida 12/17/19

Last night, I attended a pro-impeachment rally in Melbourne, Florida, a pro-Trump city. It was a fascinating experience and a harrowing one. Like most of the hundred-odd people in attendance, I had come to ask that my Congressman impeach a president who has proven unworthy of his office and abusive of his power.

youtube

Also in attendance were twenty-odd Trump supporters waving “Trump 2020″ flags the size of small billboards. They were there, apparently, to protest the protestors, to intimidate us, or worse, bait us into violence.

For many of the Trump supporters, the strategy was to single out a protestor, charge at him or her, phone in hand, video recording, and try to goad the protestor into reacting. It was like when a basketball player jumps into the defender to draw a foul. My hunch was that they hoped to use the power of the camera phone--traditionally a liberal tool--against the liberals. My hunch was that most of them learned about the camera phone’s power from the many recordings of unarmed black men killed by police officers. My hunch was that, because these recordings exposed a truth we cannot admit and threatened a power we cannot acknowledge, they remain at the heart of how and why we got here. Listening to the chants and taunts, it was clear we weren’t fighting about impeachment. No, we were fighting about Eric Gardner, Colin Kaepernick, Trayvon Martin. We were fighting about a black president. We were fighting the Civil War.

A man in a cardboard-cutout Trump mask, giant flag in hand, said, “I support Trump because Obama was the biggest racist ever. He hated cops, and he tried to make everyone else hate cops.” This was a popular talking point on Fox News during Obama’s tenure. It matters little that it is untrue. It matters less that it shows an almost stunning ignorance of what racism is and how it has shaped American life, policing included. There is no conversation to be had. The weight of history will not shake his belief. All we can do is shout at each other.

On one side, the protestors were too often baited into inane arguments and personal attacks. They relied on vapid chants, reducing complex issues to bumper-sticker slogans. Perhaps this is the best an angry crowd can do. As for Trump’s supporters, what disturbed me most was the obvious glee they took in cruelty. They weren’t there to defend Trump’s record, such as it is. They were there to make people they despise feel scared, and threatened, and small. This was hard to know and feel. These are not just my countrymen; they are members of my community.

Sadly, the protest was less an exercise of a vital civil right and more an internet comment thread come to life. Imagine watching two adults, face to face, features twisted, fingers pointed, screaming at each other: Baby killer! Racist! Go home and eat your fetuses! Imagine a man of about fifty mocking a girl of about twenty-five: Are you going to cry? Do you need tissues? Triggered! Snowflake!

Occasionally two people would attempt a reasonable conversation. These were the most disingenuous moments of all. Shouting was what we wanted. We were ugly. Have you ever been in an argument where you realized the other person really, truly wanted to hurt you, and you wanted to hurt them back? That’s what this was. Resentment. Disdain. Naked hatred. We can’t live together. Not like this.

Of course, none of this is new. What is remarkable is how steady it has been, how the battle lines have stayed in place since 2016 with little movement. People at the protest were still shouting about Benghazi. Maybe some of the issues have changed, but again, we weren’t fighting about issues. The world as we know it is unraveling, and we all feel it. The fight, at its core, is about power. Who will define and build and profit from whatever comes next?

Over the last years, I’ve been noting the uncanny ways life has begun to imitate movies. Take the ominous black shadow on Trump’s face when he wears a baseball hat, like he’s Emperor Palpatine in Return of the Jedi. Take the black Christmas trees, black as sin and coal, at the White House. I think what bothers me most is how amateurish and easy the symbolism is. The devil was supposed to be slick, not some sweaty goon in a cheap suit.

The end of last night’s protest was full of that same broad symbolism. Black clouds sickened the sky. A deluge fell. Rain, angry rain, pummeled us as we fled for cover. Over the driving drumming rain came eerie chants: “Lock him up! Lock him up!” “Four more years! Four more years!” As the storm’s fury spent itself, a woman unfurled a monstrous “Trump 2020″ flag and waved it under a violent black sky. A professional lighting crew couldn’t have done better at capturing the sense of impending doom, of evil on the march, of a people broken apart. Not fractured. Broken.

Whether Trump wins or loses in 2020, the break will fester long after he is gone. This is us. This is who we are.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curtis Mayfield’s Grammy Disaster

Super Fly had earned four Grammy nominations, and Curtis received an invitation to perform at the ceremony in early March 1973. Perhaps it was the added pressure of success, or perhaps it was the increased consumption of weed, but whatever the reason, that night his insecurities mushroomed into full-blown paranoia. When the time came for his performance, he waited in the wings while his band kicked into “Freddie’s Dead.” A fog machine spread smoky ambiance across the stage as he walked out. When he started singing, it didn’t stop blowing. For the entire performance, billows of fog blocked him from the audience’s view. He felt like a fool in front of his peers, not to mention the people tuning in on TV.

"Freddie's Dead (Live from the 15th Annual GRAMMY Awards)" on Apple Music

Watch the music video "Freddie's Dead (Live from the 15th Annual GRAMMY Awards)" by Curtis Mayfield. Free with Apple…itunes.apple.com

Then, Super Fly lost in every category, often to songs or albums that didn’t approach its commercial or artistic impact. Curtis sulked back to his hotel room, crestfallen. His girlfriend Toni got in his ear and convinced him the whole thing was a white conspiracy — Whitey wouldn’t let a guy who sang “Superfly” win. Seething, the smoke machine’s fog still burning in his nostrils, he called Marv and demanded he cancel the white-college tour.

Manager Marv Stuart warned him, “You’re going to be so caught up in lawsuits, it’s not worth it,” but for a man who changed his mind with such ease, Curtis could also be immovable as a boulder. Marv enlisted the help of Neil Bogart, and they went to Curtis’s room to try to dissuade him, but he wouldn’t budge. They cancelled the tour, he got sued and lost a good deal of money, and William Morris refused to work with him again.

Excerpted from Traveling Soul: The Life of Curtis Mayfield. Buy it here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“All suppressed truths become poisonous”

--Nietzsche.

Just yesterday, two more unarmed black men were shot dead by the police, and so came the usual deluge. Half want justice; half believe justice was done, and they all talk to themselves about it. Everyone wants to know what’s going on. Then come the peacemakers asking: “Can’t we all just love each other?”

I don’t have recourse to any of these points of view. I have studied American history, and I know exactly what’s going on, and I know that we can’t just love each other, and I know why.

Do you want to know why cops killed two more unarmed black men? Do you want to know why they will kill more?

Because no matter where I have lived--from Miami to Manhattan--I have never been more than fifteen minutes from a ghetto, and I never even think of it. Every one of those ghettos is filled with black and brown people, and they are invisible to me unless they riot or protest.

youtube

To be fair to myself, some black and brown people would have ended up in the ghetto no matter what. But I know how the ghetto was created. I know it was purposefully set up as a trap for black and brown people by white landowners with the collusion of the U.S. government. I know this because it is a matter of historical fact. Anyone reading this can just as easily look into the creation of ghettos in America with a few keystrokes. And yet it is still invisible to me. It is my fault.

I can’t Tweet: “WTF is up America?” as a friend of mine recently did. I know WTF is up. I am white and grew up in a culture that defined black men as dangerous and black women as nonexistent. That message was fed to me like breastmilk from the time I was a baby until today. It has taken me 34 years to understand that I can’t wish that away. All I can do is sit with it and let it make me uncomfortable.

I invite you to do the same. If you’re still wondering why we can’t all love each other, or if you're about to repost a meme blaming the protestors or the victims, stop for a second. Look in the mirror. Consider the possibility that you know nothing of what African Americans have experienced. Consider the possibility that your blindness is your fault, like mine is my fault. Let it make you indignant and uncomfortable. Sit with it.

It hurts. Then again, it’s not as bad as being shot for no reason.

#dontrehamilton#ericgarner#johncrawford#michael brown#ezell ford#dante parker#tanishaanderson#akaigurley#Tamir Rice#jeramereid#tony robinson#phillip white#eric harris#walter scott#freddie gray#kalief browder#keith lamont scott#terence crutcher

1 note

·

View note

Text

AWWWWW SHIT

youtube

0 notes

Text

Check out my new project

I’m nailing New York City.

Words! Music! Video!

http://smallpotatoesinthebigapple.tumblr.com/post/140814361280/sutton-place-park

1 note

·

View note

Photo

2015: The Year That Was

It’s been a rough century. Each year seems harder than the last, until I feel I’m writing this from a bunker rather than my kitchen. One wants to shout, Enough already! A year is a hard enough distance to travel without us brutalizing each other to no end.

As 2015 ends, from all the tragedy—drone bombings, beheadings, earthquakes, mass shootings, rogue cops, et cetera, et cetera—two lessons emerge, and both are beautiful and terrifying in equal measure.

The first lesson comes courtesy of ISIS, and the seawater that floods Miami at high tide, and the young black men who were nine times as likely to be killed by a cop than any other race this year. And the lesson is this: The immutable law of cause and effect applies to us. This might seem too obvious to merit mention, and it should be, but after watching the reactions to the Islamic State, or the dire climactic spasms, or the Black Lives Matter movement, it clearly needs to be said. Everyone, from newscasters to Facebook posters, was wondering this year—why is ISIS terrorizing us? Why is the sea threatening to wash an entire city away? Why are thousands marching in the streets of Baltimore?

Only a nation that assumes it is above the law of cause and effect could be so blind to have to ask these questions. This blindness, I believe, is a result of living in an empire—in order to do the dirty work of building one, a people has to believe it is special, chosen, elevated beyond simple cause and effect. The problem is that ISIS, and Baltimore, and Miami remind us that, while you can topple governments and arm unstable and bloodthirsty factions that will fight on your side only as long as it suits their needs, and while you can enslave and oppress and degrade people for four hundred years, and while you can consume and pollute endlessly in the steely-eyed quest for profit, you cannot do it free of charge. And nothing seems to upset our national psyche more than when the bill comes in.

The second lesson—and it is a son of a bitch—comes courtesy of a black boy named Kalief Browder. In 2010, the sixteen-year-old, nicknamed Peanut because of his small stature, was sent to Riker’s Island for a crime he didn’t commit. In fact, there was almost no evidence to convict him, but due to the vagaries of the justice system, he spent three years in jail with no trial. He was beaten repeatedly, threatened, and degraded, but what ultimately broke him were the two years he spent in solitary confinement. After his release, Browder tried to kill himself twice. He said, “I’m not all right. I’m messed up. I know that I might see some money from this case, but that’s not going to help me mentally. I’m mentally scarred right now. That’s how I feel. Because there are certain things that changed about me and they might not go back.” Then, on June 6, 2015, he pulled out a window-unit air conditioner in his apartment, crawled through the hole with a cord wrapped around his neck, and jumped. His mother heard a noise, rushed outside, and saw her youngest child dangling from a noose, dead.

The lesson in Browder’s death strikes at the heart of everything else that has happened this year, and it is this: We need each other to survive. Literally. This is a scientific fact, and the effects of solitary confinement give brutal testament to that fact. Humans are hardwired to need interaction with each other on a biological level, and when that interaction was taken from Browder, he never recovered. But the lesson is bigger than one teenager. We also need each other on a societal level, to make sure our basest instincts don’t ruin what is best about us—that prejudice, and fear, and misinformation don’t replace justice, and courage, and honesty. And we need each other on a global level, too, as the sea begins to reclaim South Florida, and droughts threaten to undo California, and corn withers and dies on the stalk in the unprecedented Midwest heat. It’s going to take all of us to survive.

It’s not clear what can be done to make 2016 better. Since we purport to be a Christian nation, even though we follow almost none of the rules of Christianity, the mind comes back to a Jewish prophet, arguably among the most misunderstood individuals in history. He said, “Whatsoever you do to the least of my children, that you do unto me.” There’s truth in that, whether he said it or not. What we do to one, we do to all. It would do us well to remember it. Unfortunately, that same prophet also said something else, and we follow it with much more zeal—“I come not to bring peace, but the sword.”

The sword hangs over our heads now. What are we going to do about it?

0 notes

Text

Rockefeller Center

There’s no place like New York at Christmas. Manhattan can corrode your soul--it’s like living in a jar of battery acid--but come December, the city finds a reserve of childish wonder that is truly a wonder to behold. From the jollily festooned carriages in Central Park, to the hovering snowflake star on 5th Avenue; from the ice skaters glissading below the giant tree at Rockefeller Center, to the window-shoppers gawking outside Bloomingdale’s--Christmas magic takes root in barren soil and grows into a symbol of our shared humanity. It’s like finding a stalk of grass on Mars.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Becoming White

“The Irish middle passage, for but one example, was as foul as my own … But the Irish became white when they got here and began rising in the world, whereas I became black and began sinking.”

James Baldwin, “The Price of the Ticket,” 1985.

How am I white?

After Rachel Dolezal, the Charleston shootings and the racial violence that claimed so many black lives recently, many are asking what it means to be black in America today, but few are asking what it means to be white. And in that latter question lies an integral part of the equation. The fact is, as Baldwin wrote, most white Americans are not white. They became white. This distinction is important, and to understand what is happening today, those of us who became white must understand how and why we did so.

My great-grandmother fled Syria nearly one hundred years ago. She was herded into the cargo hold of a ship and spent the long passage to America rocking sickly in the dark. She had to ride below deck because she wasn’t white. She married another Syrian and settled in Irwin, Pennsylvania, a predominantly Irish-German town. The Irish, still struggling with their own journey out of the social gutter, taunted my family with the epithet ubla-ubla, a dig at the sharp, guttural sounds they made when speaking Arabic. It didn’t take my great-grandparents long to learn their dark olive skin and curly black hair worked against them in this new home.

So how am I white?

My mother’s father was a second-generation Syrian-American. At Ellis Island, his father’s surname made a miraculous translation from Dayoub to Sam, and in grade school, his teacher advised his class, “Don’t drink coffee, because your skin will turn brown like George Sam’s.” My mother tells similar stories of her own life—how kids called her “little black Sam” and “Sambo,” and asked if she was “colored” because her hair was black and curly, and her skin was dark.

So how am I white?

My father’s grandfather sailed from Sicily near the turn of the century. He settled in New Jersey and earned twenty-five cents a day as a cobbler. Too poor to afford housing, he slept beneath his workbench. When he ventured out of the Italian neighborhood, he was called dago, and wop and guinea.

So how am I white?

The answer is both impossibly complex and incredibly simple. I’ve spent much of my life trying to understand it, studying American racial history and researching the civil rights movement and race in the 20th century for a book I recently completed. Here’s what I found—I am white because, even though my family entered this country in a low social and economic position, and even though they weren’t considered white by the racist standards of the time, they also weren’t black. That meant they had access to opportunities like bank loans, which meant home and land ownership were possible. They were smart with those opportunities and grew them into wealth. Wealth gave them access to the power that had drawn them to America in the first place, and regardless of what they had to do to get it, and despite the fact that the power could never quite change their immigrant status, it meant their children, and their children’s children, had a chance to enter life with the highest social, economic, political and cultural status in the world. They could be white Americans.

If this seems far fetched, consider a few historical facts. My great-grandfather, the one they called ubla-ubla, worked at a glass factory. Would the factory have hired him if he was black? Knowing the well-documented racist history of labor unions, probably not. My other great-grandfather, the one they called dago, received a bank loan to build his own shoe store and eventually bought and sold property in New Jersey. Would these opportunities have been open to him if he was black? Knowing the well-documented racist history of bank loans and land ownership, it’s highly unlikely.

None of this is to diminish my family’s, or any immigrant’s, accomplishments. We earned our position. We worked terrible jobs for low pay and somehow clawed out enough to save and build upon. But through the generations, we escaped the prejudice we faced on arrival and blended into the fabric of white American society. That’s how I began life as an ordinary white guy, not a Syrian or Sicilian immigrant. This is a luxury no black American has ever had, and one few white Americans acknowledge today.

If my family didn’t become white, I certainly wouldn’t have grown up the way I did, with the opportunities I had. Take my education, for instance. During my school years, roughly 400,000 black people lived in my hometown of Hollywood, Florida, and its surrounding counties, according to the September 1992 edition of American Demographics magazine. Yet, in my entire elementary school, there were two black kids—twin brothers, no less. In middle school, I don’t remember any. In high school, maybe half a dozen per class.

These schools were parochial and private—my friends in public schools had a different experience. Still, while learning about slavery, segregation and the civil rights movement, no one asked why, in an area with nearly half a million black people, fewer than forty of them went to school with us. And although nearly every one of my white classmates came from an immigrant family that became white like mine, none of us questioned how our world, our race or our identity was constructed. Perhaps we were too young to form the question, or perhaps our segregation was so near complete, nothing in our experience even hinted there was a question to be asked.

This should alarm all of us. Americans made a promise to be better than this. Better than segregated schools and unequal opportunity. Better than racist church massacres and police brutality. That promise shines in our founding documents. It punctuates every political speech we give, every patriotic song we sing, every history book we write. Sometimes it seems it’s everywhere but in our actions.

So what do we do? For starters, we can take Baldwin’s advice from “The Price of the Ticket,” where he urged, “Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it.”

I am white. I know how I became white. Do you?

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Check out my new project, Small Potatoes in the Big Apple.

Songs! Words! Pictures! Video! Field Recording! New York!

0 notes

Photo

Paralyzed by the Past: Notes on Father John Misty, Ryan Adams and Taylor Swift

“ . . . to be paralyzed by a past no longer relevant.” - Joan Didion

Recently, Father John Misty, former Fleet Foxes drummer and creator of the lauded I Love You, Honeybear, covered Ryan Adams covering Taylor Swift. Listening to it made me uncomfortable. Let me tell you why, if I can—there are two main reasons, and they exemplify why my generation (I was born a year after Misty) has failed musically.

I must first put some parameters on what I mean by “my generation.” I am speaking specifically of the indie rock generation—the roughly 25 years from the late ’80s to the present day (peaking in the late 2000s) when just about every white musician in the world seemed somehow unaware of hip-hop and returned endlessly to 1960s rock ‘n’ roll until we inbred all the sex and danger and novelty out of it.

The first issue is, while Misty’s covers seem to be a dig at Adams rather than Swift, I think there’s more at play. For an indie artist of his generation to cover a pop star is an inherently ironic act. Whether he means it to or not, by covering Taylor Swift, Misty is feeding into a culture that places him at an ironic distance above her. In other words, he’s slumming it, deigning to descend from his artist’s perch and get his hands dirty with commoners making—gasp!—pop music. Again, whether he means it or not is immaterial. His generation, my generation, perceives the irony regardless. And if that kind of irony still strikes us as artistry, we are all the worse for it.

The second and more important reason I felt uncomfortable is that Misty’s freakishly accurate Lou Reed impression sounds more like a damnation of his own music than anything. Misty’s real music, good as it may be, is a distinctly backward-looking affair. First with Fleet Foxes and now on his own, his greatness comes from sounding like other artists who were great 40 years ago. That’s the indie ethos in a nutshell. Our metric of artistic achievement is how much you sound like your heroes. The only source of novelty in our music comes from which combination of past musicians you decide to rip off. We were lousy at co-opting hip-hop, which was the cutting-edge popular music of our time, so we retreated to the well-worn well of Beatles, Stones, Beach Boys, Bowie, Ramones, et al., and we got trapped in that well like so many Baby Jessicas. We’re still trapped.

Don’t take my word for it. Listen to Robert Schneider of the Apples in Stereo, and one of the founders of the Elephant 6 collective that includes Of Montreal and Neutral Milk Hotel. He wrote in a recent issue of The Believer, “My friends and I who started the Elephant 6 music collective wanted to be like [Brian] Wilson and our other psychedelic idols, and to see through their eyes. What would the genius do? I’d ask myself, and then study old studio photographs to see what they had actually done. I taught myself to record by trying to recreate my idols’ sessions.”

He says more here than he thinks. Even at indie rock’s inception, its reference points were 20 years old. KRS-One, Big Daddy Kane, Nas, the Notorious B.I.G.—these artists flew over the indie rockers’ heads in a way that Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley didn’t fly over, say, Keith Richards’ head.

Of course, one could argue all new art is made by copying past idols, and that’s true in a way, but the difference is my generation added essentially nothing to what came before it. How could we? By the time we got to rock ‘n’ roll, it had already lived through half a dozen mutations. It had been combined and recombined, moved forward, pushed back, mixed and matched to the point of homogenized stasis. The new combinations left to be made were so miniscule, they couldn’t make more than a negligible mark on the whole structure. Musicians of my era, like Misty, received their wisdom second, third, even fourth hand. As a result, the music they’ve made isn’t bad; it just isn’t new. It has no gravity. You could erase Misty from history along with Fleet Foxes, the Apples in Stereo and just about every other indie band, and the legacy of rock would stand unchanged. Try saying that of Led Zeppelin or Jimi Hendrix.

But so what, I hear you say. Isn’t the point to make good music, regardless of whether or not it’s new? Perhaps. But when has an artist ever aspired to merely reproduce someone else’s ideas? Name one artist defined by a reverence for recreating the past to the point of ignoring the future. There is a name for that kind of thinking—conservatism—and it has nothing to do with politics. This is artistic conservatism, and little today is more conservative than Misty’s brand of indie rock. Like the dais at a Republican presidential debate, it is too enamored of the past and unwilling or unable to exist in a present that passed it by decades ago. Take as exhibit A the fact that many of Misty’s ilk still record onto tape and consider this a badge of honor. If John Lennon and Paul McCartney insisted on cutting straight to wax through an old gramophone the way they did in the ’20s, we wouldn’t have the Beatles.

Misty said he took the Taylor Swift covers down after Lou Reed came to him in a dream and said, “Delete those tracks, don’t summon the dead, I am not your plaything. The collection of souls is an expensive pastime.” I’m not sure he understood Reed’s meaning, though. Misty has made a career out of collecting other artists’ souls. The entire indie generation of musicians has. And it is indeed an expensive pastime. We’ve paid with our own souls. We are, to borrow a phrase from Nobel-laureate V.S. Naipaul, mimic men.

Taylor Swift might be the only winner here. She belongs to a generation that doesn’t seem to need the same ironic quotation marks around its every action—one that doesn’t have the albatross of the 1960s around its neck. She’ll outlive Misty because she is simply a more important artist. She makes pop music, and pop music, for good or ill, is perpetually new. It has no past, no history. It can only look forward, while rock ‘n’ roll is mired in the paralysis Didion spoke of. That’s why Misty’s covers of Adams covering Swift ring sour. Because in his Lou Reed impersonation, I don’t hear a joke.

I hear the whimper of a generation, my generation, paralyzed by a past no longer relevant.

#taylor swift#taylor swift 1989#father john misty#ryan adams#indie rock#hip-hop#rock and roll#rock & roll

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

There is nothing like puking with somebody to make you into old friends.

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

0 notes

Text

Becoming White

“The Irish middle passage, for but one example, was as foul as my own . . . But the Irish became white when they got here and began rising in the world, whereas I became black and began sinking.”

James Baldwin, “The Price of the Ticket,” 1985.

How am I white?

After Rachel Dolezal, the Charleston shootings and the racial violence that claimed so many black lives recently, many are asking what it means to be black in America today, but few are asking what it means to be white. And in that latter question lies an integral part of the equation. The fact is, as Baldwin wrote, most white Americans are not white. They became white. This distinction is important, and to understand what is happening today, those of us who became white must understand how and why we did so.

My great-grandmother fled Syria nearly one hundred years ago. She was herded into the cargo hold of a ship and spent the long passage to America rocking sickly in the dark. She had to ride below deck because she wasn’t white. She married another Syrian and settled in Irwin, Pennsylvania, a predominantly Irish-German town. The Irish, still struggling with their own journey out of the social gutter, taunted my family with the epithet ubla-ubla, a dig at the sharp, guttural sounds they made when speaking Arabic. It didn’t take my great-grandparents long to learn their dark olive skin and curly black hair worked against them in this new home.

So how am I white?

My mother’s father was a second-generation Syrian-American. At Ellis Island, his father’s surname made a miraculous translation from Dayoub to Sam, and in grade school, his teacher advised his class, “Don’t drink coffee, because your skin will turn brown like George Sam’s.” My mother tells similar stories of her own life—how kids called her “little black Sam” and “Sambo,” and asked if she was “colored” because her hair was black and curly, and her skin was dark.

So how am I white?

My father’s grandfather sailed from Sicily near the turn of the century. He settled in New Jersey and earned twenty-five cents a day as a cobbler. Too poor to afford housing, he slept beneath his workbench. When he ventured out of the Italian neighborhood, he was called dago, and wop and guinea.

So how am I white?

The answer is both impossibly complex and incredibly simple. I’ve spent much of my life trying to understand it, studying American racial history and researching the civil rights movement and race in the 20th century for a book I recently completed. Here’s what I found—I am white because, even though my family entered this country in a low social and economic position, and even though they weren’t considered white by the racist standards of the time, they also weren’t black. That meant they had access to opportunities like bank loans, which meant home and land ownership were possible. They were smart with those opportunities and grew them into wealth. Wealth gave them access to the power that had drawn them to America in the first place, and regardless of what they had to do to get it, and despite the fact that the power could never quite change their immigrant status, it meant their children, and their children’s children, had a chance to enter life with the highest social, economic, political and cultural status in the world. They could be white Americans.

If this seems far fetched, consider a few historical facts. My great-grandfather, the one they called ubla-ubla, worked at a glass factory. Would the factory have hired him if he was black? Knowing the well-documented racist history of labor unions, probably not. My other great-grandfather, the one they called dago, received a bank loan to build his own shoe store and eventually bought and sold property in New Jersey. Would these opportunities have been open to him if he was black? Knowing the well-documented racist history of bank loans and land ownership, it’s highly unlikely.

None of this is to diminish my family’s, or any immigrant’s, accomplishments. We earned our position. We worked terrible jobs for low pay and somehow clawed out enough to save and build upon. But through the generations, we escaped the prejudice we faced on arrival and blended into the fabric of white American society. That’s how I began life as an ordinary white guy, not a Syrian or Sicilian immigrant. This is a luxury no black American has ever had, and one few white Americans acknowledge today.

If my family didn’t become white, I certainly wouldn’t have grown up the way I did, with the opportunities I had. Take my education, for instance. During my school years, roughly 400,000 black people lived in my hometown of Hollywood, Florida, and its surrounding counties, according to the September 1992 edition of American Demographics magazine. Yet, in my entire elementary school, there were two black kids—twin brothers, no less. In middle school, I don’t remember any. In high school, maybe half a dozen per class.

These schools were parochial and private—my friends in public schools had a different experience. Still, while learning about slavery, segregation and the civil rights movement, no one asked why, in an area with nearly half a million black people, fewer than forty of them went to school with us. And although nearly every one of my white classmates came from an immigrant family that became white like mine, none of us questioned how our world, our race or our identity was constructed. Perhaps we were too young to form the question, or perhaps our segregation was so near complete, nothing in our experience even hinted there was a question to be asked.

This should alarm all of us. Americans made a promise to be better than this. Better than segregated schools and unequal opportunity. Better than racist church massacres and police brutality. That promise shines in our founding documents. It punctuates every political speech we give, every patriotic song we sing, every history book we write. Sometimes it seems it’s everywhere but in our actions.

So what do we do? For starters, we can take Baldwin’s advice from “The Price of the Ticket,” where he urged, “Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it.”

I am white. I know how I became white. Do you?

#charleston#james baldwin#rachel dolezal#racism#civil rights#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black lives count

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

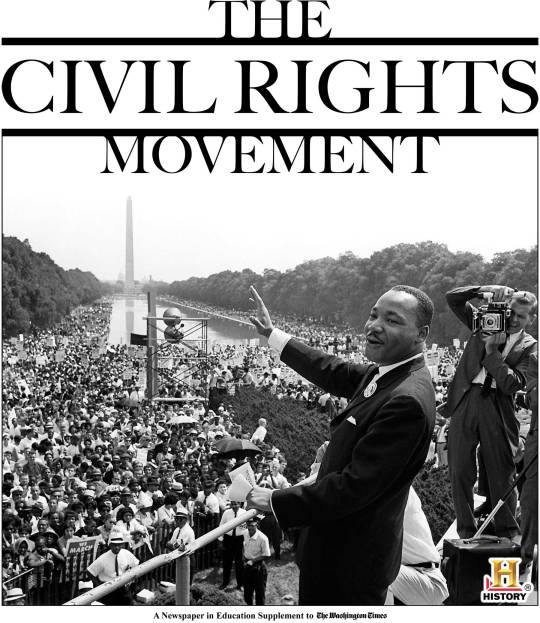

Time to Reevaluate the Civil Rights Movement

by: Travis Atria

After the massacre at a South Carolina church and Kalief Browder’s suicide, it’s clear the recent nightmare of racial violence that claimed Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner is nowhere near ending. Of course, to call it “recent” isn’t accurate—it is part of a four-hundred-year history of violence. But why is it still happening in 2015? And what do we do about it?

There is one answer to these questions that hasn’t been said much, if at all—we must reevaluate the civil rights movement and pierce our lazy reverence for it with the truth that it failed.

This is not a new opinion. Not long before his death, Martin Luther King said, “The decade of 1955 to 1965, with its constructive elements, misled us. Everyone underestimated the amount of rage Negroes were suppressing, and the amount of bigotry the white majority was disguising . . . but we must admit there was a limitation to our achievement.” That limitation was summed up nicely by civil rights leader James Farmer. In 1992, he said, “We did wipe out Jim Crow for all practical purposes. We just overestimated the impact that would have on changing the life condition of the black American.”

I say we have a lazy reverence for the era because we tend not to examine or challenge its dominant narrative. In simple terms, the narrative goes like this: Slavery led to segregation, which led to the civil rights movement, which led to America’s redemption. That’s what I was taught in school, on television, in movies, and everywhere else. I bet you learned it too.

It’s a pretty lie, but it has consequences. It requires us to disconnect modern racism from the past. In other words, racism is now a personal failing, not a social one. Thus, no one on the news (or on Facebook, it seemed) could fathom why Ferguson, Missouri went up in flames. Thus, Wednesday’s slaughter at the South Carolina church is being covered in some quarters as a single act of insanity, not as an extension of the racist terrorism that killed four little girls in the 1963 bombing of a black Birmingham church. After all, didn’t the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action fix the problem?

Unfortunately the past will not disconnect from us. And here’s where redefining the civil rights movement becomes so important. If we reframe it specifically in terms of its main achievement, as the struggle that ended legal segregation, we give ourselves much needed room. Room to question and examine the ways in which we are still as brutal and oppressive in the year 2015 as we were in 1915, or 1815. Room to hear what that brutality does to its recipients. Room to continue the work begun by King, Farmer and the movement.

If, on the other hand, we continue to treat the movement as the endpoint to the struggle, we shouldn’t be surprised when 2065 looks a lot like 1965.

#charleston#blacklivesmatter#tamir rice#eric garner#kalief browder#martin luther king#martin luther quotes

0 notes

Photo

Sticks and Stones: As Liberals, We Must Focus Our Energy Better

By Travis Atria

I’m as thin-skinned, bleeding-heart liberal as they come. I agree with the idea that people, even comedians, should consider the effect of their words before saying them. But the reaction to Trevor Noah’s mildly offensive, not very funny Tweets has me worried. Fellow liberals, we are in danger, and the danger is ourselves.

We are like an overactive immune system, mistaking itself for an enemy and attacking.

It's not the criticism directed at Noah that's bad, it's the nature of it. The hysterical (and I don't mean funny) reaction is so far beyond what the situation calls for, it puts important liberal causes in danger of becoming too easy to write off as just a bunch of bleeding hearts overreacting again.

If we have no sense of scale, if the slightest offense causes the biggest outrage, how can anyone take us seriously when we get really offended at Ferguson, or at gay bashing masquerading as religious freedom, or at the gender pay gap? By freaking out over some bad jokes from 2009, we make all of our reactions suspect.

Because the fact is, we are in a war. A war for gay rights, a war for gender equality, a war for racial equality, a war for economic and political fairness. There are very real forces aligned against these causes.

And it doesn’t take a four-star general to know that if you send all of your troops to every battle, no matter how small or insignificant, you will lose that war and quickly.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vagina Hearts and Dandelion Heads: Notes from Björk at Carnegie Hall

by:Travis Atria

Björk is waiting in the wings. She’s wearing something that covers her entire head, something that makes her look like a giant dandelion. I say “something” because I still can’t tell what it is, even after examining pictures of it closely. This headpiece is important for reasons no one has yet mentioned. In fact, so much about Björk is important in the same way. We’ll get to that in a moment. First put yourself in Carnegie Hall with me.

The Hall’s decor demands a sense of awe—it drips with European filigree, which is the only way Americans know how to make a building seem awesome—all burgundy plush velvet and ornately carved pillars. Now make the letter “C” with your left hand, and that is the shape of Carnegie Hall’s seating arrangement. The stage is placed at the opening of the “C,” so that it extends from your forefinger to your thumb. Sit with me in a cramped opera box on the second level. Your seat, looking at the “C” again, is somewhere near the base of your thumbnail. It isn’t the best view of the stage, but you can see straight into the backstage area where the forty-nine-year-old Icelandic phenomenon stands waiting to wash over the crowd with her latest album, the crushing Vulnicura.

Preceding her onto the stage are percussionist Manu Delago, Venezuelan producer/DJ Arca, and a fifteen-piece string orchestra. Then, the woman herself. The crowd’s reaction reminds you of a football game. It isn’t just respectful—it is rabid. This brings up another important thought, but we’ll get to that in a minute, too.

She opens with “Stonemilker,” a song about heartbreak that is so perfectly drawn and sung, it sneaks up on you and becomes you, insinuates itself inside you. It stops all thought. You realize that Björk isn’t singing about her recent breakup from her longtime partner and the destruction of her family. She is describing your own experiences of heartbreak with a precision you’ve never imagined. It is hard to explain this feeling. In a way, it is a profound release. She has done all the work. All you have to do is listen to understand yourself.

The song ends and the crowd’s reaction is almost embarrassing. Such a level of shouting, whistling, screaming, clapping in Carnegie Hall is surely improper. Which brings us back to that rabid applause when she came out, and the important thought that came with it. An artist is someone who has the courage to stand emotionally naked in front of complete strangers. Björk is such an artist, and our rabid applause comes, at least in part, from our relationship to her courage. We respond to it on an elemental level because so few of us have it.

This brings us to the first aspect of Björk that is misunderstood, or at least not often mentioned. Her courage is so great, it allows (compels?) her to create music so original that it actually limits itself. This fact illuminates the narrow nature of being an iconoclast, which Björk is. In other words, Björk can’t be anything but Björk. She has defined a new world in music, and as a result she is stuck in that world. She exists on a very narrow band of experience. You don’t take Björk to the beach, for instance.

This is why you love her, and also why, by the end of a two-hour-long concert, you’re exhausted. Björk requires intense work from the listener. She rarely gives the ear what it wants to hear. She gives it what she wants it to hear. At no point does she capitulate with an easy beat you can tap your toes to, or a melody you can predict, if not understand. Her music doesn’t seek to engage you. It demands that you engage with it. More than that—and here comes that courage again—whether or not you engage with it doesn’t matter. Her music will not be denied. It is a force. Engage with it or not, your choice exists in relation to it, and the music will stand either way.

Perhaps the most misunderstood part of Björk, however, is her sexual power. Reviewers tend to paint her as impish, girlish, almost immature. This is incorrect. Björk uses sexuality in her work in a powerful and mature way that few female artists have done, or are allowed to do. In her videos, she has gone fully naked and explicitly sexual but always in bizarre, challenging ways. Her recent installment at the MOMA in New York features a video showcasing her embrace of vaginal imagery, as does the cover for Vulnicura, which features her in an outfit on which appears what can only be described as a vagina-heart.

She uses many of the same tools as sex-positive artists like Madonna or Lady Gaga—outlandish costumes, an intense physicality in videos—but the difference, it seems, is that Björk isn’t interested in shock value. In a very real way, she is the descendent of modernist and surrealist female artists of the 20th century. Visually, she is Georgia O’Keeffe meets Frida Kahlo wearing black latex. Watch the video for “Pagan Poetry” and you might see a moving O’Keeffe painting with Björk wearing a sort of S&M version of the dress in Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.” Even that dandelion headpiece outfit she wears at Carnegie Hall—here it comes again—is a sort of freaked out, modern version of Kahlo’s “Self Portrait as a Tehuana.” Clearly, the lines between the three female artists are not straight ones, and they might not even be conscious ones for Björk. But the point here is, like O’Keeffe and Kahlo, Björk’s work is an open threat to a patriarchal art world. It reclaims female sexuality—the most physically creative force on Earth—as an artistically creative force.

All this might be too academic, but few will disagree that the music industry—and the society it serves—are male dominated. Some will take that to the logical next step of asking why, and that is a dangerous question. Björk forces that question simply by standing on that stage and having the courage to face us with honesty.

After playing most of Vulnicura and encoring with a few older songs, Björk exits, followed by her band. The rabid applause explodes like shrapnel once again, nearly 3,000 people begging for one more encore. From your seat you can see her standing in the wings, and you know she is not coming back. She has given all she can give. She has sounded the depths of her heartbreak and your own. She has exposed her courage and touched your latent courage.

The rest is up to you.

4 notes

·

View notes