Link

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte asked Congress on Monday to extend martial law across the southern region of Mindanao by one year in order to guarantee the “total eradication” of Isis and communist fighters, warning that remaining militants have been regrouping since their unsuccessful siege of Marawi City ended in October.

In a letter to the Philippine Senate and the House of Representatives, which was later released to the media, Duterte said how a one-year extension was necessary to allow for government forces to combat uprisings by Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) and to also stall radical groups from establishing the next regional emir.

“[Current] activities are geared towards the conduct of intensified atrocities and armed public uprisings in support of their objective of establishing the foundation of a global Islamic caliphate and of a Wilayat not only in the Philippines but also in the whole of Southeast Asia,” Duterte was quoted as saying in the letter.

BIFF fighter Abu Turaifie and Furuji Indama, a high-ranking cell leader in the Abu Sayyaf terror group, have both had their names put forward as possible contenders to become the region’s next emir. The former leader, Isnilon Hapilon, was gunned down by armed Philippine forces in October.

The martial law extension would mean for a continued presence of army surveillance in the region, which also includes giving the authority to arrest suspected terrorists or people colluding with extremists without a warrant.

In the Philippines, martial law must first receive approval from Congress to go past the original 60-day limit, but there is no cap on how many times it can be extended.

Duterte’s request for an extension has been widely met with criticism from pro-democracy groups, who claim the move is a human rights violation and highlights the president’s growing inclination towards authoritarian practices.

Karapatan, a human rights group, released a statement that questioned why martial law is even being considered for extension, particularly since it’s been nearly two months since the military won the battle against extremist groups in Marawi City.

The group went on to explain that this recent request provides clear evidence of a “dangerous precedent that inches the entire country closer to a nationwide declaration of martial rule.”

Human rights lawyer and House politician Rep. Edcel Lagman also argued that Congress should reject Duterte’s request, as his arguments were constitutionally weak, ABC reported.

Lagman went on to explain in a statement that since Duterte had already declared Marawi to be free from terrorist influence on 17 October, he had no legal ground to continue to suggest that there was a threat of invasion or rebellion within Mindanao.

As quoted to the ABC, Lagman said it would be a “patent violation of the safeguards which the 1987 constitution imposes for the limited grounds and duration of martial law and its extension.”

Lawmakers will vote on the request for a one-year extension at a joint session on Wednesday, with a final decision expected by Friday.

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

By: Jhoanna Ballaran - Reporter / @JhoannaBINQ

INQUIRER.net / 12:44 PM December 13, 2017

A party-list lawmaker proposed on Wednesday for the nationwide declaration of martial law because of the threat posed by communist rebels.

But Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana immediately assured that threats posed by the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in Luzon and Visayas are “manageable” that it may not be sensible to also place the two regions under martial rule.

During the special joint session of Congress to tackle President Rodrigo Duterte’s request to extend martial law in Mindanao, Kusug Tausug party-list Rep. Shernee Tan noted the presence of NPA in Luzon and Visayas, and thus, urged that martial law be declared all over the country.

“Mr. Speaker, there are still NPA (New People’s Army), and they could also make a tax in Luzon and Visayas, therefore, as representative of Kusug Tausug party-list, I reiterate my stand that martial law should be extended not just in Mindanao but also in Luzon and in Visayas if it serves to the best interest of our nation,” Tan said.

Lorenzana, however, appeared to be cold about the suggestion.

He said: “I think the reason why the NPA in Mindanao are included is because of the intensity…kasi po malakas yung…45 percent of the NPA in the whole Philippines are in Mindanao. And they are creating havoc, especially in eastern Mindanao.”

“In Visayas and Luzon manageable po yung activities ng CPP-NPA diyan, kaya I don’t think that would be [advisable] to spread or to include Visayas and Luzon in the martial law,” he further said.

Inquirer calls for support for the victims in Marawi City

Responding to appeals for help, the Philippine Daily Inquirer is extending its relief to victims of the attacks in Marawi City

Cash donations may be deposited in the Inquirer Foundation Corp. Banco De Oro (BDO) Current Account No: 007960018860.

Inquiries may be addressed to Inquirer’s Corporate Affairs office through Connie Kalagayan at 897-4426, [email protected] and Bianca Kasilag-Macahilig at 897-8808 local 352, [email protected].

For donation from overseas:

Inquirer Foundation Corp account:

Inquirer Foundation Corp. Banco De Oro (BDO) Current Account No: 007960018860

Swift Code: BNORPHMM

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

MANILA, Philippine – A year after former president Ferdinand Marcos was buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani, minority senators honored the “true heroes” who expressed outrage against the hero’s burial of the late dictator.

“On this day, let us choose to remember not the burial but the people who rose to the call: protesters who showed a strong sense of hope, pride, and solidarity,” the senators said in a statement on Saturday, November 18.

They are Senators Paolo Benigno Aquino IV, Leila de Lima, Franklin Drilon, Risa Hontiveros, Francis Pangilinan, and Antonio Trillanes IV.

Marcos was buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani on November 18, 2016, a week after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of his hero’s burial. The private burial rites were done in secret, as requested by the family, sparking condemnation from groups and personalities opposed to the hero’s burial.

The secret burial triggered nationwide protests where “true heroes” converged, the minority senators said on Saturday.

“While a false hero was being buried at the Heroes’ Cemetery, true heroes were rising to the challenge and making their voices heard. All across the country, we saw the power of a people who never forgot the truth about this dictator. Crowds numbering in the thousands gathered to condemn the disrespect and utter shamelessness of the secret funeral,” they said.

#the martial law thingy#martial law#philippines#marcos#ferdinand marcos#sad emoticon thoughts#libingan ng mga bayani

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

Opposition lawmakers have rejected the proposed extension of martial law in Mindanao beyond 2017 despite the liberation of Marawi City from the Maute group, arguing that such an option would be a far cry from normalcy.

“Martial law must be the very last option,” said Caloocan City Rep. Edgar Erice, a member of the “Magnificent Seven” opposition bloc at the House of Representatives.

“It’s a solution that would have costly side effects on our democratic institutions. It’s a quick fix that would eventually turn out not as the solution to our problems in Mindanao,” he told reporters.

Armed Forces of the Philippines spokesperson Maj. Gen. Restituto Padilla told a Malacañang press briefing that the military might seek an extension of martial law in Mindanao to allow government forces to eradicate the remaining threats to the region.

Under a presidential proclamation approved by Congress, the imposition of martial law in Mindanao will lapse on Dec. 31.

Ifugao Rep. Teddy Baguilat Jr. also said extending martial law in Mindanao beyond 2017 would not normalize the situation in the strife-torn region.

Not a permanent solution

“Martial law will not normalize the situation. Investments will not come in. Distrust by the Muslims on the administration will persist with military rule,” he said.

Baguilat shared Erice’s view that martial law should not be seen as a permanent solution.

Temporary response

“The military has to understand that martial law is a temporary response to an extraordinary security problem such as rebellion and invasion,” he said.

He said Congress and the Supreme Court had “bent the rules and trifled with the Constitution” to give President Duterte the mandate to use martial law in repressing the Maute group along with other terrorist groups and Islamic State sympathizers.

“Now that the Maute group has been obliterated, the government should now focus on rehabilitation efforts in Marawi, and social and political reform in Mindanao,” Baguilat said.

Climate of fear

Akbayan Rep. Tom Villarin said it has become the Armed Forces’ “habit” to look at martial law as the only solution to terrorism and all peace and order problems.

“It creates a climate of fear and surrender by our people of their freedoms to strongman rule. The Marawi tragedy is now unfortunately being used to justify a sweeping policy approach of containing terrorism and a peace process negotiated under the nozzle of the gun,” he said.

“This creeping authoritarian rule is sapping our democracy and any vestiges of the rule of law. By having unlimited martial law, we cater to the desires of President Duterte to hold power beyond the mandate of our Constitution. Such desires become a clear and present danger to democracy,” Villarin said.

1 note

·

View note

Link

On 17 October, President Rodrigo Duterte declared the “liberation of Marawi” following the military assault that killed Omar Maute and Isnilon Hapilon, the two militant leaders who mounted the siege. Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana subsequently ordered the termination of combat operations, an indication that government forces have fully reclaimed the city.

But crushing the militant heads and gaining full control of the city is a military victory against a violent extremist group; it does not mean that violent extremism has been brought to an end. As I’ve argued previously at New Mandala, heavy handed use of military firepower such as heavy artillery and airstrikes—which have indiscriminately swept away entire communities—can trigger spin-off extremist movements under new leaders who are even more difficult, dangerous, and deadly than their predecessors.

My recent work with civilian evacuees in Marawi reemphasised that extremism can emerge if government authorities continue to fall short in addressing the concerns of the displaced Maranao population. The Marawi crisis affected more than 300,000 Maranao residents, of whom nearly 80% are home-based evacuees—that is, staying with host families, most likely their friends or relatives. Others remain housed in cramped evacuation centres that suffer from difficult living conditions. Out of the 96 barangays (villages) in the city, 33 of these are believed to be heavily damaged because they are located in the main battle areas. Government programs addressing the plight of the evacuees during the height of the conflict have been limited, leaving far too many unclear about their future.

Keep reading

58 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Philippine military has killed two senior commanders of the Isis-affiliated military groups behind the deadly siege in Marawi City in an operation that defence secretary Delfin Lorenzana believes will lead to “the termination of hostilities in a couple of days”.

Abu Sayyaf leader Isnilon Hapilon and Maute leader Omar Maute were killed in the early hours of Monday morning, after a hostage who had previously been held captive by the rebels helped government troops locate the building in which the two leaders were hiding.

“We have received a report from [Armed Forces of the Philippines] ground commanders in Marawi that the operation conducted by government forces to retake the last remaining Daesh-Maute stronghold in the city has resulted in the death of the last terrorist leaders Isnilon Hapilon and Omar Maute, and that their bodies have been recovered by our operating units,” said Lorenzana.

The military’s recent offensive led to the release of 17 hostages, according to Zia Alonto Adiong, spokesperson for the Marawi Crisis Management Committee.

Hapilon, who is listed as one of the FBI’s most-wanted terror suspects, and Maute have long been in the crosshairs of the Philippine state.

Earlier this year, the country’s President Rodrigo Duterte placed a reward of ten million Philippine pesos ($195,330) for the assassination of Hapilon, who is widely considered the ‘emir’ of Isis in Southeast Asia. Hapilon also had a $5m US bounty on his head for carrying out multiple ransom kidnappings and beheadings of US citizens. The Philippine government had also offered a five million peso reward for Omar Maute.

Lorenzana said that the deaths of the two leaders signalled that the military was just days away from bringing an end to the conflict. Lorenzana added, however, that it was too early to consider ending martial law on the island of Mindanao.

The conflict began after a failed military raid to capture Hapilon on 23 May. Hundreds of thousands of Filipinos have been displaced since the fighting broke out. The conflict has claimed the lives of 813 rebels, 47 civilians and 162 military, according to Philippine authorities.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Uncharismatic President

The “Poor Boy from Lubao”, as he campaigned himself in the 1961 Philippine general elections, was said to be a shrewd politician and an uncharismatic man. The late Senator Ninoy Aquino described him thus:

People respected him but he aroused no real love, adoration, idolatry–and that’s important in a political leader. For a man like Magsaysay you could work 24 hours a day and still not feel tired–but, for a politician, Macapagal was dry: stingy with praise, low to appreciate, not demonstrative, not communicative.

Many social commentators of the time agree with this assessment. He was described as a tireless workaholic, and a bore. But what made Diosdado Macapagal stand out and win the Presidency was his uncanny dedication for the poor. Some more sophisticated people in Manila winced whenever he went abroad to represent the country, perhaps from a perceived uncouthness, but this rough edged candidate may have contributed to his win.

He was, after all, an unprecedented presidential candidate.

Prior to 1961, he served as legal assistant to Presidents like Manuel Quezon, and Jose P. Laurel. In times of war and in peace, as public servant in the Palace and later on as Congressman, he had consistently sided with the masses, but not to the point of capturing the populist sentiments of the time, like Magsaysay. The turning point was in 1957, when he ran for the Vice Presidency, with his running mate Emmanuel Pelaez. Macapagal won, but with a President of an opposing party.

*Liberal Party candidates, Macapagal (left) and Pelaez (right), in the campaign trail for the 1961 Presidential Elections. Photo from the Presidential Museum and Library.

It was the first time in Philippine history that the President and the Vice President belonged to different parties. Hence, President Carlos P. Garcia, in a break with tradition, took offense and did not give Macapagal a position in his Cabinet. But it was Garcia’s grave mistake. Macapagal, going beyond his mandate as Vice President, had four years of his term to tour the country, implement social programs, and making sure that the people know his name.

Come the 1961 elections, when Garcia, who initially announced that he would retire, heard that Macapagal was running as president under the Liberal Party ticket, he decided to run again for reelection, and understandably lost. Macapagal was uncharismatic, but at least he was perceived to be sincere in wanting a change in political values, and priorities.

As writer Napoleon Rama described him, “No one in our history has risen so high in government service from so humble beginning.” It was so humble in fact, that when his opponent’s party, the Nacionalistas, tried to look for any skeletons in Macapagal’s closet, they found nothing. He owned no house or land when he ascended the Presidency.

*Diosdado Macapagal swears an oath as the 9th President of the Philippines on December 30, 1961. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

But three months into his presidency, the Harry Stonehill scandal exploded on Macapagal’s face. Stonehill, a corrupt businessman who contributed to Macapagal’s campaign, had been implicated by whistleblower, Meinhart Spielman. The mysterious “blue book” that Stonehill had, listed all the politicians that he colluded with, and Macapagal’s name was there. In a swift stroke of a presidential pen, even before the Senate hearing began on Stonehill, Macapagal had Stonehill deported to the United States, and fired his Justice Secretary Jose W. Diokno. Diokno was the one who initiated the raid on Stonehill’s office and found implicating documents against the President.

But Macapagal initiated some earth-shaking programs in the country. He signed the first Land Reform law that tremendously lessened the burden of farmers. He pushed for the Philippine claim on Sabah in the International Court of Justice at the time when Malaysia was newly formed. And in the backdrop of the United States’ rejection of the proposed World War II reparation bill for Filipinos, and with influence from reputable Filipino historians, Macapagal changed the date of the commemoration of Philippine independence from July 4 to June 12.

During his term, he lived a very frugal life, even rarely using the luxurious presidential state car lent to him. But he remained a mysterious man in the public eye, who “left no clear-cut imprint of his personality.” But he was the first president to have a comprehensive program for government, although he found it hard to make the large bureaucracy of government understand this.

After his term, Macapagal was elected president of the 1971 Constitutional Convention, tasked to amend the 1935 constitution. However, plagued with scandals and political maneuverings involving the Marcos administration, and the subsequent declaration of Martial Law on September 23, 1972, the convention was a failure, and the constitution as envisioned by Marcos prevailed, extending his term and changing the government structure to parliamentary government under constitutional authoritarianism.

Macapagal eventually opposed the dictatorship. He formed the National Union for Liberation Party to contend with Marcos, and later on revealed that he found the new constitution questionable.

In all this, I think we need to face the reality that presidents are as imperfect as the people who elected them. We will never have a perfect president. Misunderstood though Macapagal was, and highly suspected by the public of his time (as it should be on any ruling president), his legacy is here to stay. And there is good in this legacy. Let us build on the good that he began.

“Corruption in government, like sin in man, may not be completely eradicated. But it can be minimized to a degree as to be tolerable to the attainment of robust economic growth and an edifying social progress.”

- Diosdado Macapagal

*Painting above comes from the Presidential Museum and Library website. It is the second commissioned official portrait of President Diosdado Macapagal, painted by Rolando Ponce Lampitoc Sr. in the style of Fernando Amorsolo.

In commemoration of the 107th birth anniversary of the late President Diosdado Pangan Macapagal, yesterday.

The text of this blog is based on my lecture delivered at the President Diosdado P. Macapagal Museum and Library at Lubao, Pampanga on 28 September 2017.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

#NeverAgain: Martial Law stories young people need to hear

by Shakira Sison

It’s convenient to look at the past with rose-colored glasses instead of with memories of needles in your nail beds, electric wires attached to your genitals, and the barrel of a gun thrust inside your mouth.

Majority of comments on articles about Martial Law seem to be from staunch defenders of that era. There are and will always be citizens who see those years as an era of peace and prosperity in our country.

We don’t need to debate that. Instead we simply need to tell, retell and listen to the stories of those who survived those years. As the younger generation we need to do our own research, take the blinders off our eyes and learn what exactly life was like during Martial Law before coming up with flowery images of those years as a beautiful moment in history.

Silence by force

You would never have seen an article such as this as I would have already been taken, tortured, and killed for my opinions. If Martial Law were still in effect, bloggers who wrote anything even remotely critical of the government or its cronies would be jailed like they do in other countries.

There would be none of your Facebook rants about the administration, Metro Manila traffic, or even the outfit a politician is wearing. In fact, there wouldn’t be Facebook, Instagram, and Gmail in the Philippines the way these websites are banned in China.

If I wrote during Martial Law, I could be taken from my home the way 23-year-old Lily Hilao was for being a prolific writer for her school paper at the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila. In April 1973, Lily was taken by the military, and was raped and tortured in front of her 16-year-old sister. By the time Lily’s family retrieved her dead body, it bore cigarette burns on her lips, injection marks on her arms, bruises and gun barrel marks. Her internal organs were removed and her vagina was sawed off to cover signs of torture and sexual abuse. Liliosa Hilao is considered to be the first female casualty and martyr of Martial Law.

Zero criticism

Martial Law engineer Juan Ponce Enrile defined subversion during a 1977 BBC interview: “anybody who goes against the government or who tries to convince people to go against the government – that is subversion.” Proclamation 1081 gave the military the authority to arrest, detain, and execute anyone who even dared to breathe sadly about the Marcos administration.

Archimedes Trajano was only 21 when he questioned Imee Marcos on why she was the National Chairman of the Kabataang Barangay during an open forum. He was forcibly taken from the venue by Imee’s bodyguards, and was tortured and thrown out of a building window, all because the presidential daughter was irked by his question.

Maria Elena Ang was a 23-year-old UP Journalism student when she was arrested and detained. She was beaten, electrocuted, water cured, and sexually violated during her detention.

Dr Juan Escandor was a young doctor with UP-PGH who was tortured and killed by the Philippine Constabulary. When his body was recovered, a pathologist found that his skull had been broken open, emptied and stuffed with trash, plastic bags, rags and underwear. His brain was stuffed inside his abdominal cavity.

Boyet Mijares was only 16 years old in 1977 when he received a call that his disappeared father (whistleblower and writer Primitivo Mijares) was still alive. The caller invited the younger Mijares to see him. A few days later, Boyet’s body was found dumped outside Manila, his eyeballs protruding, his chest perforated with multiple stab wounds, his head bashed in, and his hands, feet and genitals mangled.

Trinidad Herrera was a community leader in Tondo when she was arrested in 1977. In this video she recounts being electrocuted on her fingers, breasts, and vagina until her interrogators were pleased with her answers to their questions.

Neri Colmenares was an 18-year-old activist when he was arrested and tortured by members of the Philippine Constabulary. Aside from being strangled and made to play Russian Roulette, he witnessed fellow detainees being electrocuted through wires inserted into their penises, as well as being buried alive in a steel drum.

Hilda Narciso was a church worker when she was arrested, confined in a small cell, fed a soup of worms and rotten fish, and repeatedly gang-raped.

Necessary methods

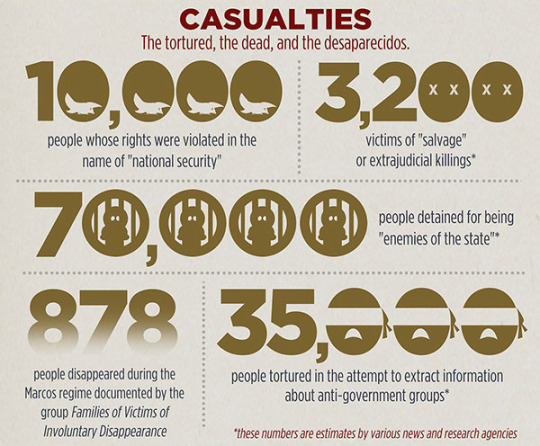

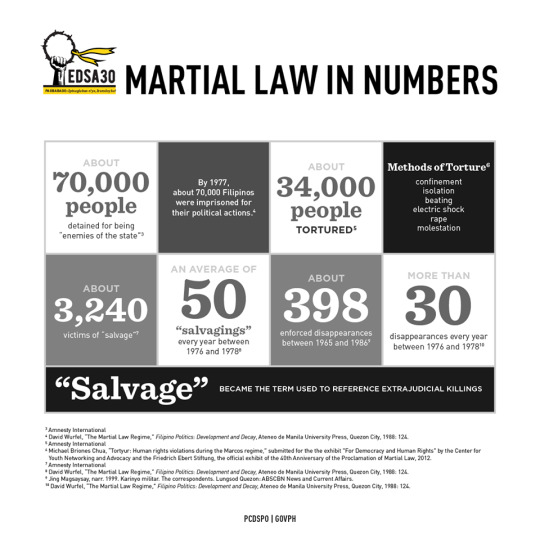

60,000 were arrested during the first year of Martial Law alone, and many of their stories will never be told. Michael Chua wrote a paper detailing the torture methods used during the Marcos regime.

Aside from electrocution of body parts and genitals, it was routine to waterboard political prisoners, burn them using cigarettes and flat irons, strangle them using wires and steel bars, and rub pepper on their genitals. Women were stripped naked, made to sit on ice blocks or stand in cold rooms, and weresexually assaulted using objects such as eggplants smeared with chili peppers.

Forty-three years have passed. Time, as well as the circus that is Philippine governance make it easy to forget Martial Law as the darkest and most terrible moments in Philippine history. Many of its victims have died or have chosen to remain silent – silence being most understandable because these stories are truly difficult to remember, and much harder to tell.

Stories need to be told

Yet these horrific stories need to be told over and over until we realize that the pretty cover of the book of the Marcos years is actually full of monster stories. We need to bring the graphic accounts of torture and murder to light so that those who rest comfortably in their illusions that the Marcos years were pleasant will at least be stirred.

Instead we often hear from those who want to erase the evils of the past, those who tell us that these young people, many of them barely past their childhoods when they were tortured and killed, were violent rebels who sought to overthrow the government. Never mind that it was one of the most corrupt and cruel dictatorships the world has ever known, and that it was by the efforts of these young heroes that the reign of the Marcoses ended.

Majority of Martial Law victims were in their 20s and 30s at that time – the same age our younger citizens are now – those who have the luxury of shrugging off the Marcos years as a wonderful time. Unscathed by a more cruel past, the younger generation is only too eager to criticize the current state of our government and our people as being undisciplined and requiring an iron fist such as the one Marcos used to supposedly create peace in the past.

They forget that if we were still under Martial Law (or should it return), such sentiments of “subversion” could cost them their lives, and that the same freedom and voice they use to reminisce about a time they know nothing about would have been muted and extinguished if we did not have the democracy we enjoy today.

Hindsight is always 20-20, as they say. It’s convenient to look at the past with rose-colored glasses instead of memories of needles in your nail beds, electric wires attached to your genitals, and a barrel of a gun thrust inside your mouth, the way thousands of Martial Law victims suffered and still suffer to this day.

Just because it didn’t happen to you or your family doesn’t mean it didn’t happen to more than 70,000 victims during that time. Just because you were spared then doesn’t mean you will be spared the next time this iron fist you wish for comes around. – Rappler.com

@thisisnotpilipinx @useless-philippinesfacts @repvblikangpilipinas

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[Source: Google Drive from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines]

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[Source: Google Drive of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines]

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[Source: Presidential Commission of Good Government (PCGG) Facebook]

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Road to Martial Law Redux: A Conclusion to the Series

How apt that I end this series the day before the Supreme Court issues its judgment on whether or not Ferdinand Marcos should be buried in Libingan ng mga Bayani. One must remember that it was also the Supreme Court (a compromised one) that ended any legal debate on the constitutionality of Martial Law in 1973. More than four decades after, we are here once again in the precipice. And whatever the verdict of the Supreme Court is, will have reverberations in how succeeding generations of Filipinos would view heroism, the entire depth and breadth of the Marcos years, and will have a lasting impact on the national narrative and ongoing historical discourse. It’s a scary thought.

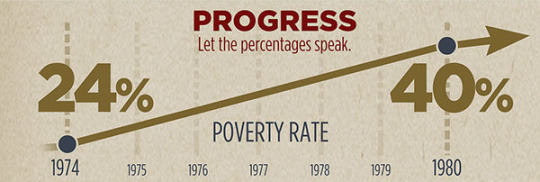

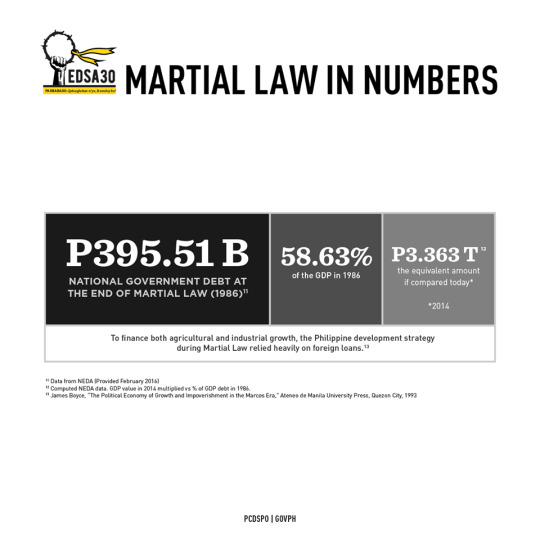

We never expected that we would arrive at this point in the national discourse, where the very concept of ‘heroism’ would be challenged and reshaped by the prevailing revisionism peddled by the current administration. Conferring the “hero” status to a dictator who was clearly responsible for much of the country’s economic woes (The debt incurred by the Marcos administration would be paid by the country in full only in the year 2025), corruption in government bureaucracy and perpetrator of human rights violations–it boggles the mind. The segue that Marcos loyalists insist is that the law does not explicitly prohibit the burying of Marcos at the National Heroes Cemetery. It was clear he was awarded the Medal of Valor, and it’s because of this, alone, disregarding the excesses of his regime, that they say he should be buried, with full military honors. But it takes a child to point out that this argument selectively blinds itself from the real issue, that one cannot separate the entire being of a president to his Medal of Valor (and his other medals proven to be fake), failures, and grave abuse of power.

Which brings me to the wise interpellation of Associate Justice Marvic Leonen during the oral arguments of the Supreme Court last month, to the Solicitor General who insisted on the same aforementioned Marcos loyalist argument: “Which part of President Marcos is called a hero, and which part isn’t?”

The whole history and the integrity of the overwhelming evidence hangs on us all. As actress Rachel Weisz who portrayed historian Deborah Lipstadt in combating Nazi historical revisionism, in the upcoming film Denial (2016), said:

“The freedom of speech means you can say whatever you want. What you can’t do is lie and expect not to be accountable for it. Not all opinions are equal.”

youtube

*Trailer of the upcoming movie, “Denial” (2016) portraying historian Deborah Lipstadt who contended with Hitler apologist David Irving in the British court. It is a highly recommended movie for historians who seek to put historical revisionism at bay.

Let me repeat that. Not all opinions are equal. Especially when truth and the validity of evidences where it rests are under attack by notions that these are just allegations without proof. Let me be blunt. That is a lie.

Which is why I have aimed in this blog series to lay out the roots of why such a Marcos came about in the Philippine political scene. As evidences I have presented unfolded, there are nuances to be considered, and an effort for the reader to understand the entire political scene. History is a harsh judge says Gregoria de Jesus, the widow of Andres Bonifacio, especially when that part of history being scrutinized do not even leave any shadow of doubt on what has really transpired.

As we have seen in the rise of Marcos and the snuffing out of democracy on that fateful day of September 23, 1972, the creeping erosion of institutions that safeguarded freedom in a democracy wasn’t done in an instant. It took years of careful strategy, taking advantage of loopholes in the rule of law, bargaining with the political opposition by either sharing power and making them compromise or using the full resources of the state to silence them, positioning key loyal leaders in their respective posts, and manufacturing a crisis (exaggerating Communism, and somehow implementing city bombings and blame it to communists) to give legalistic reason to confer to the President emergency powers. Before martial law, a people free to express their discontent in reaction to widespread corruption was silenced by fear and political retribution during Martial Law. This is not an exaggeration, as historical primary sources can attest.

To echo what journalist Max Soliven wrote in his column, days before Martial Law:

“We must never, of course, underestimate Mr. Marcos. He is no fool. There is always method in what looks like madness. The Apo is a “group dynamics” expert, a practitioner of that science dedicated to the manipulation of people and the cunning exploitation of the basic weaknesses of human nature.”

Marcos was a genius. He anticipated every move of the opposition, took a great gamble on the ‘silent majority,’ framing everything in the context of “reforming society,” and the ever attractive “Bagong Lipunan.” He used cultural propaganda, military use of force, executive pressures on independent government institutions, and his and Imelda’s charisma to a people used to being ruled over.

But while it was Marcos who wielded the final axe that obliterated Philippine democracy, he was but the logical conclusion of a leadership and a generation, who, while building up power for themselves, willingly compromised their principles without hesitation, and chose political ambition over the grueling uphill fight for justice and equality for all.

The real mood of the people was the rage and passion of student activists that swept the country like wildfire, in what would be known as the First Quarter Storm of 1970. When Martial Law came and media was controlled, this pervading sentiment was immediately put under the rug. The rise of Moro separatism and the exponential growth of the Communist movement especially during Martial Law years proved that even when there was a superficial ‘peace and order’, a creeping deafness of the government on the rising poverty, coupled with the unchecked abuses of the military on the civilians, and state-sponsored forced disappearances of dissenters shattered the fabric of the nation. Massacres were implemented, political dissenters were incarcerated, in clear violation of the Bill of Rights enshrined in the Marcos-sponsored 1973 Constitution itself.

There were a fledgling few who stood up against the might and wrath of the Philippine strongman. But they were all too few, and the country suffered the longest presidential rule on the country, with only a semblance of democracy and a bill of rights only on paper. It was ever a wonder that we stuck to that volatile situation. As National Artist Nick Joaquin, in his work, Quartet of the Tiger Moon, greatly put it, under Martial Law, there was no hope of change.

“What had the thinking Filipino desperate during the Marcos years was not that the tyrant had crushed our rights and liberties but that he had shown the way for future fascists to crush us again and again, simply by being as ambitious and amoral, as arrogant and artful and avaricious as Marcos… An endless cycle of tyranny followed by tyranny followed by tyranny: such was the living death that faced us with Marcos and after. Before him, yes, there had been a long history of “violence and corruption,” but even that history had been an effort, an attempt, an impulse, however shy, at the democratic way of life. With Marcos ceased these exercises of democracy- and after him, of course, even the pretense of democracy would be discarded as opportunist and scoundrel exploited the pattern he had set. We had no future, no tomorrow–only that ever-present banality of evil.”

And then as critique to the world’s astonishment of our toppling the dictatorship in the EDSA People Power Revolution, Nick Joaquin offers the world a scathing rebuke:

“When we did not explode against that boot on our necks–that was the astonishment. When we let some fourteen long years pass with that boot on our necks–that was the astonishment. But when on the plenary nights of the tiger moon 1986 we rose against the boot on our necks–that was no astonishment. We were back to the regular, the everyday, the traditional. We had returned to normal. Because we have decided we were to have a future again, a tomorrow again, and that we didn’t have to resign ourselves to a numbing prospect of one damnable Marcos after another.

This is a revolutionary decision completely in keeping with our history, where the rate of insurrections, especially during the colonial period, comes to one revolt per year. And that’s when we mean when we argue that our 1986 tiger moon was no ‘astonishment’ but the customary, the accustomed, the habitual, the traditional, the normal. The Pinoy was back to his usual form.

So spare us your bravos.”

Is it any wonder that we are now back to zero? What gains we had are now meaningless to the administration and the powers that be who wants to resurrect the Great Marcos, the Savior of the Philippines. “Marcos pa rin” despite everything. Despite everything.

Whatever the ruling of the Supreme Court is, I rest in the comfort that even if it decides in favor of burying the dictator in Libingan ng mga Bayani, the battle does not end there. Because Truth, and the empirical evidences supporting it will catch on. It always has, and it always will. History can attest to that. It may take a while but it will catch on. And no one can hide from it. There will always be a day of reckoning.

So I pose this challenge to you dear reader. To whom much is given, much is required. Now that you know the story, responsibility is in your hands. In a democracy such as the Philippines, it is not dependent on our government, not even on Supreme Court rulings. It is in your hands, it is in your mind, that the fate of this battle will be decided.

Be on the right side of history. For even when it appears to lose, itaga mo sa bato, it will win.

Be on the side of Truth.

And that’s the wrap on the Road to Martial Law series: posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The complete IndioHistorian Blog Series for your reading.

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Marcos Beginnings

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

- A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

- Pawns in Cities lobbed with Bombs: Events leading to the Plaza Miranda Bombing

- Hijacking Democracy: The Mood before the Declaration of Martial Law

- September 21, 1972: When Martial Law Had to Wait for One More Day

- Like a Thief in the Night: Martial Law Implemented on September 22, 1972

- The Long Night Begins: Martial Law Announced on Live Television, September 23, 1972

- A Mere Scrap of Paper: The Constitutional Convention Hijacked under Martial Law

- The Final Blow: A compromised Supreme Court legitimized Martial Law

- Road to Martial Law Redux: A Conclusion to a Series

Additional reading:

National Historical Commission of the Philippines: Executive Summary on why Marcos Should Not Be Buried in Libingan ng mga Bayani

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

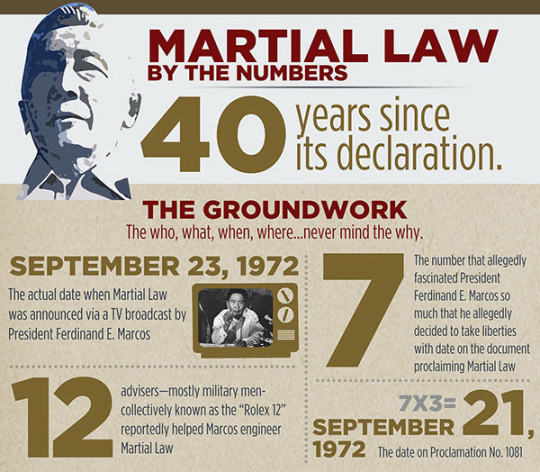

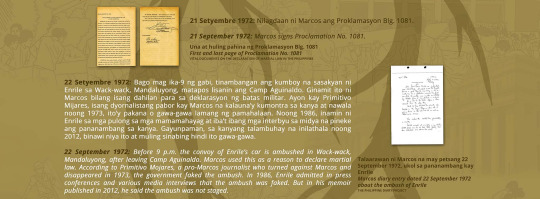

THE ANNIVERSARY OF THE DECLARATION OF MARTIAL LAW IS ON SEPTEMBER 23—NOT SEPTEMBER 21.

When President Ferdinand E. Marcos appeared on television at 7:15pm on September 23, 1972, to announce that he had placed the “entire Philippines under Martial Law” by virtue of Proclamation No. 1081, he framed his announcement in legalistic terms that, however, were untrue, and that has helped camouflage the true nature of his act, to this day: for it was nothing less than an autogolpe, or self-coup.

68 notes

·

View notes

Link

The real date guys. Martial Law in the Philippines was declared by dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos on September 23, 1972, and not on September 21.

First step to correct revisionist history.

Why September 21? Because of Marcos’ knack for numerology. The date had to be divisible by seven.

31 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Long Night Begins: Martial Law announced on live television

September 23, 1972, Midnight. It began at night, as all crimes are done. That is, Philippine democracy died in the cover of darkness. As the entire country slept soundly, President Ferdinand Marcos had sent out the military to round up the media, the opposition statesmen, activist leaders, writers, artists, all of whom have expressed a dissenting opinion or a scathing criticism on the administration, numbering to approximately 8,000 citizens. All of them would be taken by force to Camp Crame.

The first on the list of personalities to be arrested, called the “order of battle,” was reserved for none other than the face of the opposition, Senator Ninoy Aquino. Minutes before midnight Senator Arturo Tolentino, who was with the few senators that were in the Manila Hilton (now Manila Pavilion) witnessed it as it happened. They were at Room 1701. The phone had been ringing, warning the senators of the arrests. The phone rang for the last time.

It was close to midnight when the telephone rang, and the clerk who answered it called for Sen. Aquino.

Ninoy: “Yes… Who is this?… Oh, compadre…When?”

(Ninoy listened for sometime at the other end of the line)

Ninoy: “Ok, I will wait for you here.”

Ninoy returns to his chair after hanging up the phone and he said:

“Gentlemen, martial law has been declared and I am being arrested. Colonel Gatan is coming up to get me. He says he knows how many of my men are here, but he has a truckload of soldiers, so to spare lives of innocent people in the hotel he asked me not to make any move.”

At 12:10 p.m., Primitivo Mijares, Marcos’ pressman and a victim of forced disappearance wrote in his book the tensed mood inside the room.

[Ninoy said] “A dark chapter is inserting itself once more into our troubled history. I hope and pray that the dark night descending upon our beloved country would come to an early end. It’s been nice being with you, gentlemen.”

Col. Gatan enters the suite and hands Aquino a brown envelope which contains a xerox copy of an “arrest and detain” order signed by Enrile. Aquino then demanded the original document before he would come with Col. Gatan, the PC commander - with his gun holster noticeably unhooked - declared that he had personal orders from President Marcos to arrest the Senator.

Ninoy quickly shouts to his bodyguards: “Tahimik lang kayo mga bata!” then asks Col. Gatan: “Do I have any choice?”

Col. Gatan answers: “Not any more sir. I am sorry sir.”

Aquino shakes the hand of his colleagues as he went out peacefully.

As Senator Aquino was taken into the military truck by an entire military garrison, at 12:15 a.m. all radio transmission have ceased. In an age before the internet, this was synonymous to being cut off from the rest of the world. By 12:30 a.m., the 51st Army Engineering Brigade under General Amado Santiago took over MERALCO, announcing to company employees that they’re protecting MERALCO from sabotage. Minutes after, PLDT was taken over. All long distance calls coming and going out of the country were shut down. Only domestic calls were working.

By 12:55 a.m. alarmed with all the arrests, Senator Jovito Salonga called Letty Shahani on the phone to confirm if martial law had indeed been declared. She is PC Chief Gen. Fidel Ramos’ younger sister. Shahani replied, “Yes… martial law has been declared but you are not on the list.”

Meanwhile another senator was arrested. Senator Jose Diokno was in his residence along Roxas Boulevard, Manila when the military came knocking heavily on his door at approximately 1:00 am (some accounts say 3:00 a.m.). Around the same time, military troops led by Army Captain Rolando Abadilla, arrived at ABS-CBN at Mother Ignacia Street, Quezon City to raid it and shut it down. It won’t be live again for the next 14 years. An hour later, the Metrocom came and shut down the DZHP radio station. On another part of the city, at the same time, Luis Mauricio of Graphic was arrested. There were more fortunate ones, like Journalist Tony Zumel, who was forewarned by his brother in the Presidential Guard Battalion. He evaded arrest by jumpin into the Pasig River from the National Press Club when the military arrived. Activists like Satur Ocampo also escaped before the military came for them.

At 2:30 a.m. Journalist Hernando Abaya was forcefully taken in by the military. His daughter tried to call a lawyer, but the military cut off their phone line. By 3:00 am, some newswires were able to get the story out abroad that martial law was on, as another Senator, Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo was arrested at his residence in New Manila. It was around this time that Judy Araneta Roxas called on Senator Salonga to inform him of these arrests on the senators. He was told that Senator Gerry Roxas would go to Camp Crame to reason with the military.

In Port Area, Manila, company of troops in full battle gear” surrounds the building of the Manila Times Publishing Corporation, as the newspaper was subsequently shut down.

At the time, in Quezon City, the security guards of the Iglesia ni Cristo compound at Commonwealth grew frantic with the arrival of the military. The PC-Metrocom was there to shut down Eagle Broadcasting Network. As the military forced their way in, conflict ensued. It had to take the Defense Secretary himself, Enrile, to go there and negotiate with a bullhorn, to explain that Martial Law was already in effect. The guards stood down, but by the time the conflict was over, there were 12 casualties on record.

Meanwhile, Chino Roces, owner of the Manila Times, managed to evade arrest at midnight by going to Highway 54 (now known as EDSA) on his way towards the Diokno residence, but upon learning of Senator Diokno’s arrest, he went back home, packed his bags, and decided to willingly surrender. At around 3:15 a.m. Roces arrived at Camp Crame as he was taken in.

At 4:00 a.m. ConCon Delegate Jose Mari Velez, one of the staunch opposition to Malacañang intrusion in the Constitutional Convention, was arrested. At 5:00 a.m. the military arrested Philippines Free Press editor-in-chief, Teodoro Locsin Sr.

By 6:00 a.m. all those who were arrested waited in vain in a large gym at Camp Crame. Among those arrested were Senators Jose Diokno and Ramon Mitra, Jr., journalists “Chino" Roces, Cipriano Cid, Luis Mauricio, Delegates Jose Mari Velez and Napoleon Rama, Cavite Governor Lino Bocalan, and other prominent journalists, businessmen, lawyers, and politicians. The oldest detainee in Camp Crame was Baltazar Cuyugan, who is 72 years old. Locsin writes: “We were fingerprinted [and photographed]…like common criminals.”

By 7:00 a.m. Eugenio Lopez Jr., owner of the Lopez holdings, including ABS-CBN, woke up in Matabungkay, Batangas only to discover that all radio and tv were in static. He gravely perceived that Martial Law was on.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor arrived by plane in Washington D.C., where he received word from President Marcos that Martial Law was implemented. It was therefore his task to assure the United States that American interests won’t be affected by the military takeover. He met with Admiral Thomas Moorer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, John Holdridge of the National Security Council, and some time later, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, and William Fulbright of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Hence, Martial Law had America’s blessing.

Morning in Malacañang. President Marcos wrote on his diary that he was tired and sleepy, but “exultant.” By 9:00 a.m., First Lady Imelda Marcos insisted to Marcos the need to broadcast a live televised message to inform the public, instead of opting for a recorded broadcast. Marcos assigned Francisco “Kit” Tatad, Secretary of Public Information, and also Marcos’s youngest member in his Cabinet, to read Proclamation No. 1081.

That morning, across the country, there was agitation and panic, as military men patrolled the streets. TV was all static, except for Channel 9 which showed non-stop cartoon reruns. In between the shows were a text that said “important announcement later in the day.” Radio had “muzak” music.

At 10:00 a.m. some independent-minded ConCon delegates phone called each other, and knew that Martial Law was on. They dreaded this day, for it meant that there was no stopping of Malacañang’s pressure on them to draft a Constitution to Marcos’ liking. Except perhaps if the plebiscite rejects the draft, or it be appealed in the Supreme Court. By 10:30 a.m., ConCon Delegate Augusto Espiritu, writes on his diary:

“I went to the Convention Hall. The streets were almost deserted. By late morning there were still no newspapers, no radio broadcasts. In Quezon City, I saw two cars of soldiers with one civilian on the front seat in each of the cars—obviously taken into custody.

There were some soldiers at the checkpoint near the Quezon Memorial Circle, but the soldiers didn’t molest anyone.

At the Convention Hall, there was a note of hushed excitement, frustration and resignation. Now the reality is sinking into our consciousness. Martial law has been proclaimed!

Rumors were rife that our most outspoken activist delegates, Voltaire Garcia, Joe Mari Velez, Nap Rama, Ding Lichauco and Sonny Alvarez have been arrested. I met Convention Sec. Pepe Abueva and he informed me that this was what he had also heard.

The whole day, practically, was spent by us tensely waiting for some news. All sorts of rumors were floating around.”

Like a bad cliffhanger, Vero Perfecto, the official radio announcer of the government, announced that an important message would be given by President Marcos on live television by 12 noon. But 12 noon came, and nothing. Perfecto then announced that the broadcast would be delayed due to “technical difficulties.” An impatient and frustrated public waited. An insider look however, confirmed that the reason for the delay was that Marcos’s speech was not yet ready.

When one doesn’t have news of the outside world or have no idea of what’s going on, confusion and frustration would be the mood. And in that entire afternoon, rumors spread of a military coup, that military men have taken over Malacañang and had Marcos on house arrest in the Palace. Meanwhile, a hysterical Cecille Guidote told ConCon Delegate Espiritu that she feared that TV star Joseph Estrada, who was supposed to be with her on a show that day, might have been assassinated. Fears were somehow quelled by 3:30 p.m. when it was announced that that Marcos would deliver an important announcment from around 6:30 to 7:00 p.m. Hence, while most of the kids watched the cartoon reruns, many adults waited in nervous anticipation of the announcement.

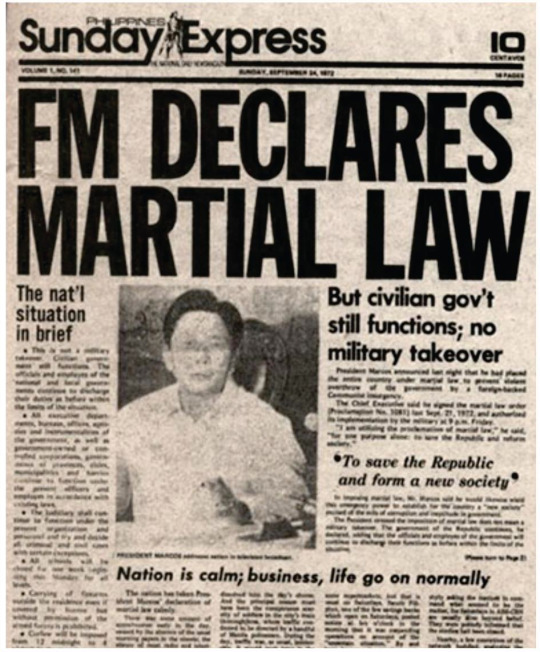

*The Sunday Express, the Sunday edition of the Philippines Daily Express, came out with the news of Martial Law, on September 24, 1972. It was the only newspaper allowed to circulate upon the declaration. Many newspapers would be allowed later on but under strict censorship of the government. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Finally, at exactly 7:15 p.m., President Ferdinand Marcos, with a solemn gaze on the camera, went live on television. He announced that under the powers of the Constitution, he had put the entire country under Martial Law. In the entire announcement, he repeatedly said:

“The proclamation of martial law is not a military takeover. It had to be done to protect the Philippines and our democracy… I repeat, this is not a military takeover… the Government of the Republic of the Philippines which was established by our people in 1946 continues. Again, I repeat. This is the same Government that you and the people established in 1946 under the Constitution of the Philippines.”

The broadcast was followed by Kit Tatad reading the text of the Proclamation No. 1081. Seemingly exhausted, Tatad kept on scratching his leg as he read the text, which earned him the title “Kamot.” ConCon Delegate Espiritu, from the live telecast, described Tatad’s reading a “sinister monotone.”

*Staff of the Philippines Free Press watching the live TV announcement of President Marcos declaring Martial Law. Source: Lopez Museum and Library.

In the Convention Hall of the ConCon at QC Hall, Espiritu recounts:

“Big Brother is watching us,” exclaimed one of the participants while looking at Tatad’s face which filled the TV frame. But this is not 1984! George Orwell showed up too early in the Philippines.

Tatad was continuously pouring out words that seemed to seal the fate of our people. We sat there and listened in mingled fear and confusion.

Sadly and fearfully, we speculated on the possible fate of our militant friends who had spoken at the ALDEC seminar, yesterday and day before yesterday. They must have been taken into military custody already. Ding Lichauco must surely have been arrested, we conjectured, and Dante Simbulan, likewise. Possibly also Dodong Nemenzo, we thought. The Korean, Moonkyoo, tried to cheer us up. He has a tape of Ding Lichauco’s lecture and he said he would tell everyone that he has the last lecture of Lichauco before he was arrested.

Meanwhile, 11 high-value detainees of the government: Senators Ninoy Aquino, Jose Diokno, and Ramon Mitra, Chino Roces, Teodoro M. Locsin, Enrique Voltaire Garcia III, Napoleon Rama, Vicente Rafael, former Senator Francisco Rodrigo, Max Soliven, and Jose Mari Velez, were placed on a bus, to be taken to an undisclosed location. Senator Aquino told Hernando Abaya before leaving, “Magtatagal ito, Hernan, seguro sa Malinta ang tungo ko,” referring to the possibility that he would be shot by a firing squad.

On the bus, the detainees were mum with dread. From Camp Crame, the bus went south of EDSA. Aquino was said to have blurted out, “If we turn right on Buendia … it’s Luneta [execution] for us.” They ended up in Fort Bonifacio. They would be allowed a one-hour daily family visit, from 5:00 to 6:00 p.m.

Marcos writes on his diary about the Martial Law announcement:

“The broadcast turned out rather well and Mons. Gaviola as well as the [illegible] friends liked it. But my most exacting critic, Imelda, found it impressive. I watched the replay at 9:00 PM.

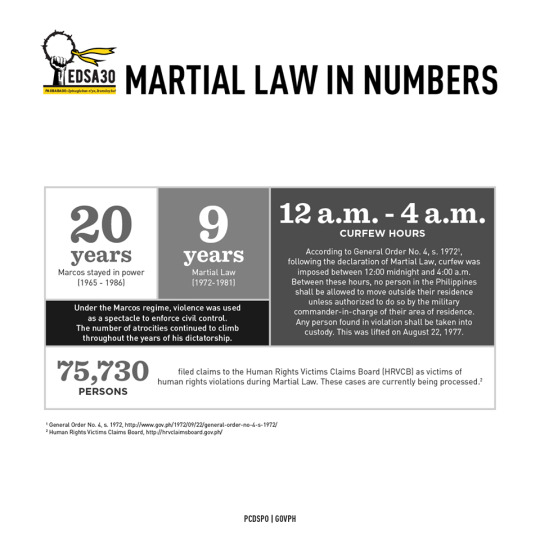

I have amended curfew from 8-6 to 12-4. Arms bearing outside residence without permit punishable by death.”

Arrests would continue for a few days, as several senators not arrested would try to make an appeal to the Supreme Court questioning the legality of the suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus. But they would not succeed.

The long night has begun.

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Marcos Beginnings

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

- A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

- Pawns in Cities lobbed with Bombs: Events leading to the Plaza Miranda Bombing

- Hijacking Democracy: The Mood before the Declaration of Martial Law

- September 21, 1972: When Martial Law Had to Wait for One More Day

- Like a Thief in the Night: Martial Law Implemented on September 22, 1972

- The Long Night Begins: Martial Law Announced on Live Television, September 23, 1972

- A Mere Scrap of Paper: The Constitutional Convention Hijacked under Martial Law

- The Final Blow: A compromised Supreme Court legitimized Martial Law

- Road to Martial Law Redux: A Conclusion to a Series

Video above:

The TV Broadcast of President Ferdinand Marcos as it was shown on September 23, 1972, 7:15 p.m.

Bibliography

Abaya, Hernando. The Making of a Subversive: A Memoir. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Enrile, Juan Ponce. Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir. Quezon City, ABS-CBN Publishing Inc., 2012.

Espiritu, Augusto, “September 23, 1972,” Philippine Diary Project, link.

De Quiros, Conrado. Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy. Pasig City: Foundation for Worldwide People’s Power, Inc., 1997.

Marcos, Ferdinand, “September 23, 1972, 12:20 p.m.” Philippine Diary Project, link.

Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. San Francisco: Union Square Publications, 1976.

Rodrigo, Raul. Phoenix: The Saga of the Lopez Family Volume 1: 1800 - 1972. Manila: The Eugenio Lopez Foundation, Inc., 2000.

Salonga, Jovito. A Journey of Struggle and Hope: The Memoir of Jovito R. Salonga. Quezon City: U.P. Center for Leadership, Citizenship and Democracy, 2001.

Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines. Dateline Manila. Pasig: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2007.

Santos, Vergel O. Chino and His Time. Pasig: Anvil Publishing House, Inc., 2010.

Tolentino, Arturo. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Press, Inc., 1990.

73 notes

·

View notes