#yon ferrets return

Photo

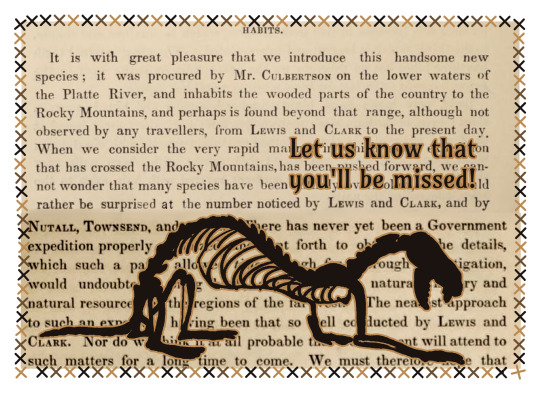

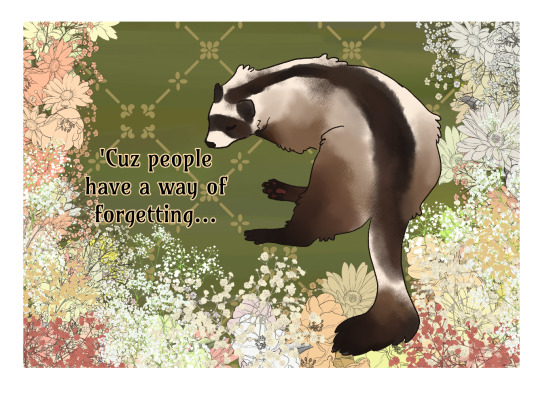

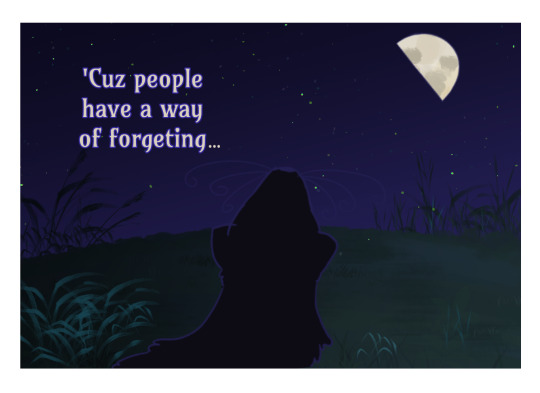

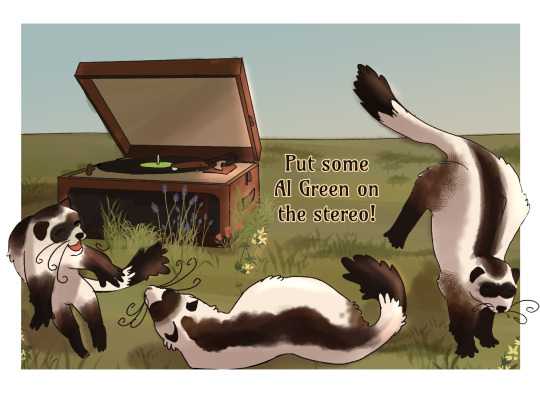

Yon Ferrets Return by Neko Case! i really love this song, so i decided to do a lil comic of it!

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ @goingtosave ]

It’s mid-day in the middle of January, and at UC Davis that generally means it’s grey and cool and otherwise no more wintery than that. This is how it’s been for most of their lives, as winters in Beacon Hills aren’t much different. But sometimes, as it turns out, it chafes a little.

Which is how Scott gets his boyfriend-beta draped over him dramatically, his expression one of theatrical wincing. “We should go to Lake Tahoe.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome home, black feet

y'all hear about the first black-footed ferret successfully being cloned a while back???

#my art#black-footed ferret#black footed ferret#animals#endangered species#ferret#drawing#yon ferrets return#Spotify

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

@volatilehearted;;

Scott is growling unhappily, his entire wolf-shaped body tense and focused at something under the bed.

Growling intensifies.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Good ass songs#Neko case#The worse things get the harder i fight the harder i fight the more I love you#Ferrets#Spotify

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

and you, my oldest friend

For the lovely @thegoldensoundtwice, based on this amazing post.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Since I moved home from college in May, I’ve kind of lost contact with a lot of good friends and colleagues, and your amazing blog has been a little bit like having a friend to chat with – especially about the wonderful world of Redwall. Even though we don’t really know each other, your kindness, sense of humor, and incredible eloquence (I will NEVER be over the fic you wrote for me!!!) has been such a gift, and so instead of studying for the GRE I wanted to write you this tale as an early Christmas present and a heartfelt thank-you. Surprise!!!

It is un-beta’d, massive af (I think almost 7K words, so let me know if you’d like a .pdf!), and a tad bit angstier than I was going for at first, but hopefully still an entertaining yarn.

Cheers!!!

It was a glorious midsummer’s evening when she saw Redwall Abbey for the first time.

Her grandfather, a silver-furred old badger named Buckthorn, had told her stories about it, of course, promising to take her there the next time they held one of their fabled feastdays. He was a good storyteller, perhaps the best in Mossflower. But even he couldn’t do it justice.

The Abbey stood tall and proud and majestic at the border of the woodlands, battlements and belltower of ruddy sandstone soaring to the sky. The setting sun gilded the myriad ivy leaves that crept across the stone, turned the climbing roses to an incandescent shade of ruby red. The broad main gates stood open to all comers, and inside she could see colored lanterns glowing in the branches of the trees, reflecting in swirls of red and yellow on the surface of a tranquil pond.

Constance had never before seen anything quite so beautiful.

A motely group of squirrels, mice, hedgehogs, otters and moles welcomed them to table at once, as if they were old friends, and loaded their plates with the most delicious-looking foods a creature could imagine: breads and cheeses, salads and pasties, puddings and berries and flans. All of them were talking at the same time.

“Welcome, both of you! You look famished! Here, this plum cake goes perfect with clotted cream.”

“How about some of this hotroot soup?”

“Don’t be shy, take a few more of these nunnymolers.”

They were given places of honor at a table of Abbey Brothers and Sisters, pleasant mice in cowled brown robes. Being rather solitary by nature, Constance spoke with them only when spoken to, preferring to let her grandfather hold the conversation. She devoted the rest of her attention to eating serving after serving of the scrumptious food and watching the other jolly creatures with interest.

As supper was winding down, with everyone sipping their favorite drinks and nibbling at their favorite sweets, some of the woodland guests, the two badgers included, took it upon themselves to provide entertainment for their kindly hosts. A troupe of voles played reels and jigs on a battered bodhran and sweet-toned reed flutes; a family of harvest mice performed several comedic skits. But Constance and Buckthorn’s act was the most anticipated of the evening. Many Redwallers had never even seen a badger in the fur before, as old Mara, Redwall’s last badger mother, had gone to her rest many seasons ago. The pair of them performed feats of marksmanship with yew longbows, and Constance obligingly wrestled stout waterhogs and burly otter champions, shaking them off like raindrops as the Redwallers shouted words of advice and encouragement.

“That’s the stuff, missie!”

“Hohoho, ole Skip’ll be sore for a full season!”

“Hurr, moind the choild don’t toss ’im into yon pudden!”

She enjoyed the competition, the adrenaline, the feeling of her own strength. The attention was slightly overwhelming. Having humored her hosts, she left her grandfather deep in conversation with old Abbot Cedric and slunk off to the orchards with a pawful of mushroom and leek turnovers, throwing herself down on the cool grass to eat. The night air was velvety-soft, sweet with the perfume of rose and blackberry and late blossoms, and she snuffed appreciatively at it between bites of savory pastry.

“Peaceful, isn’t it?” said a quiet voice, surprisingly close at paw.

Constance bristled slightly, but then relaxed when she spotted the creature, resting against the trunk of a neighboring plum tree. He was just a young mouse, dusky brown, wearing the sandals and sage-green habit of a novice. His eyes were wise and kind.

“I always like to come here in the evenings,” he continued. “It’s nice to sit and watch the sun set over the Abbey. And it’s especially nice to be surrounded by all these good creatures, and hear them laughing and enjoying the feast.”

“I live with my grandfather in Mossflower. I’ve never seen so many creatures all at once,” Constance said. It was unlike her to admit something like that to a strangebeast, but the mouse’s gentle manner somehow put her at ease.

“Do you have many friends in Mossflower?”

“Not really.”

“Well, now you’ve got lots of them here.”

Constance had to smile at that. She extended a broad black paw and gave his a gingerly shake.

“I’m Constance. Pleased to make your acquaintance, friend.”

The mouse made a grave gesture in return, bowing his head over his own folded paws.

“My name is Mortimer,” he said.

By the end of the feast Mortimer and Constance were inseparable; the one’s serious nature perfectly complemented the other’s slight shyness. When she and her grandfather returned for the autumn harvest he showed her around the interior of the Abbey: the dizzying height of the belltower, the best places to sit in Great Hall, the labyrinthine aisles of the cellars where their resident Cellarhog kept special firkins of mulled wine and flowery mead.

Of course, they were both still young creatures, so these sights were soon followed by a tour of the spookiest corners of the attic, the hallways with the best curtains to shelter behind during games of hide-and-seek, and the kitchen larders that held the best snacks. They played in the crisp autumn leaves and dared each other to step paw in the icy pond. He also introduced her to Martin the Warrior, explaining the legend to her as she gazed, transfixed, at the richly embroidered tapestry.

“A mouse fighting a wildcat,” she marveled aloud. “I can’t wait to tell my granddad about this.”

“I thought you’d like to know about Martin,” said Mortimer. “He was brave and strong like you.”

“And then a mouse of peace, like you,” she replied thoughtfully.

Buckthorn was growing too old to make the journey to Redwall as often as Constance would have liked, and so in the springtide she argued and pleaded with him until, finally, he gave her permission to make the trip on her own. She woke well before dawn, packed a generous haversack of supplies, and set out through the woodlands at a steady pace, already full of excitement for the day she had planned. The miles passed swiftly. She arrived at the Abbey by midmorning, just as the Redwallers were finishing their breakfast, and stealthily motioned for Mortimer to leave Great Hall and join her in the orchard. He was thrilled by the surprise, but also full of questions.

“Why are you being so secretive? Where’s your grandfather? How in the name of seasons did you get here so early?”

“I’m here to take you on an adventure,” she told him in a stage whisper. “Think you can sneak out to Mossflower for the day?”

“I’m not sure I’m allowed,” said Mortimer. “I have to help with the washing for the dormitories and –”

“Come on! I’ve been to Redwall lots of times, now you should see where I live. Just tell them you can’t do it! Make something up!”

“I’ll try. Wait here.”

He disappeared for several minutes, leaving Constance to sample some of the early gooseberries. Finally he returned with a subdued expression and a heavy green travelling cloak draped over his Redwall habit.

“I told Brother Oswin I was gathering herbs for the infirmary,” he said, already self-reproachful.

“Don’t worry, it won’t be a fib. We can find some on the way back.”

He cheered up as soon as they set paw in the emerald forest, where new leaves were budding and a kaleidoscope of varicolored wildflowers were blooming. He had never been so far into Mossflower Wood before. Constance named the many birds for him by their plumage and their dulcet voices, and Mortimer paused often to admire fuzzy bumblebees and jewel-toned dragonflies, or flitting butterflies with wings like stained glass.

After a few hours’ march they sat down on the riverbank to rest, shaded by the boughs of an ancient willow. Mortimer said a simple grace over their midday meal. Constance watched the way his eyes closed, his shoulders relaxed, his paws steepled.

“What is it like, being in the Order?” she asked him, around a mouthful of strawberry preserves.

“Well, there’s a lot of book learning.” He brushed oatcake crumbs from his lap and cut a wedge of yellow cheese studded with hazelnuts, whiskers twitching thoughtfully. “Lots of history. We learn about the founders of Redwall and where they came from, and about the rules and vows that all Abbeymice live by. But our most important duty is to provide help and healing and charity to any creature in need of our assistance. Just a few days ago there was a poor weasel with a racking cough –”

“You mean you let vermin into the Abbey?” Constance interrupted.

“He was an honest creature. Sister Teazle and I made him a draught of strong herbs. He was as good as new by the next morning, and gave us some beautiful mussel shells in token of his thanks.”

“He probably came by those while he was off pirating at sea,” she replied dryly. “I know you don’t want to hear this, but you can’t trust just anyone. There are a lot of dishonest creatures who would try to take advantage, even here in Mossflower. We’ve had quite a few brushes with robber foxes and ferrets.”

“Trust them or not, my duty is to help them if they require it,” Mortimer said patiently. “But I suppose it’s safer living at Redwall than out here in the forest.”

“I don’t know. It’s not so bad.”

“Oh dear, I didn’t mean it that way at all, truly. Mossflower is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen. I think I could stay here by the riverside forever.”

“Well, I think Redwall’s got to be the best place I’ve ever seen,” said Constance, pleased by her friend’s compliment.

“Who knows! Maybe you could come and live there someday.”

After luncheon they crossed the stream, picking a careful path over the slippery stones, and made their way at last to at the badgers’ cottage. It was a snug little house of smooth clay, built back against a rock shelf so that the soft-mossed surface served as the fourth and largest wall. Trailing nasturtiums wove over the doorway and windowsills, their flowers like bright medallions of orange and sun gold. Inside were tables and chairs of Buckthorn’s making, carved out of honey-colored wood, and little trinkets from his many travels: pressed mountain flowers, many-colored stones, bits of seaglass worn smooth as silk.

“It reminds me of our Cavern Hole at Redwall,” said Mortimer, his eyes aglow.

“A neighbor helped me to build this place, a clever old beaver, when I first came to this part of the woods.” Buckthorn straightened from stoking up the hearthfire. “That were when young Constance here was but a tiny badgermaid. Her gran was still with us then.”

“She must have planted that wonderful herb garden of yours.”

“Aye, that’s right. She was a healer like you are, y’know. There’s some rare plants growing there that might interest you.”

The old badger and the young mouse were kindred spirits. Over the course of the afternoon Buckthorn swapped stories with Mortimer and shared with him some of the badger lore that Constance had known since she was a cub, the workings of the tide and the secret phases of the moon, the way to sense the first changings of the season – even old fireside tales, like that of the great snow badger who brought deep winter to Mossflower Wood. Constance was just about to remind them that they needed to get back to the Abbey before nightfall when a sudden spring rain began to lash through the trees, obscuring the woodlands with a heavy sheet of silver.

“Not travelin’ weather, I’m afraid, young ’un,” said Buckthorn, shaking his grizzled head. “You’ll have to stay here for the night.”

“Oh, no,” Mortimer groaned. “I’m going to be in a lot of trouble when I get home.”

“Don’t worry. We can leave as soon as the sun rises,” said Constance, secretly ecstatic that the elements had intervened. “Let’s have a cup of tea, and then I’ll show you how to make a seafaring dish my granddad taught me. Skilly and duff!”

In the morning, as promised, they set out at a run with the first rays of dawn, slipping and squelching on the muddy road. Though they made it to the Abbey in record time, Mortimer’s prediction was soon proved correct. Brother Oswin was waiting for them at the gate with a face like yesterday’s thunder. Without hesitation he took hold of Mortimer’s habit sleeve and began lecturing the young mouse severely.

“We were up all night worrying about you. Abbot Cedric was about to send out a search party! And where in the fur is the sanicle and valerian you were supposed to be gathering?”

Constance blushed at the Brother’s righteous fury, beginning to feel sorry for the part she had played in the whole affair. But Mortimer, recalling the sleepless night they had spent telling tales and playing games while the rain drummed on the cottage roof, could only smile.

For many happy seasons they visited back and forth in this way, growing up and growing ever closer, Constance trekking to the Abbey for feastdays and bringing Mortimer back to the cottage to enjoy languid spring and summer evenings by the riverside. She eventually taught him how to find his way through the woodlands unaccompanied by reading the signs of moss and leaves, and after much effort prevailed upon him to carry a stout ash staff with him on the road (“Someday I won’t be there, and you might have to defend yourself!”), though only because he decided he could use it as a walking stick.

Mortimer made his way to the den often in the winter days when Buckthorn’s health began to fail him, brewing soothing teas and medicines, keeping him company while Constance slept. When the old badger went to his final rest it was Mortimer who said the funeral service, tenderly placing a bundle of early quince on the grave Constance had hacked from frozen ground.

Several days had passed since then, and the two of them sat at table together, sharing a jug of blackcurrant wine to drive off the icy chill. Constance was red-eyed but composed.

“I was thinking of taking some time to myself. Travelling someplace new, like my granddad liked to do.”

“Outside of Mossflower?”

“Perhaps.” She drained the last dregs of her cup, set it carefully back down on the tabletop. “He told me a lot of stories about Salamandastron, the mountain of the fire lizard, where his father and brothers ruled. Maybe it’s time for me to pay a visit there.”

“But surely not until the springtide, friend.”

“No. No, I’ll wait until the snow melts.” Seeking to reassure him, she gave Mortimer a tired smile. He had taken his final vows and now wore the wide-sleeved brown robe of an Abbey Brother, which made him look, if possible, more solemn than ever. “But the sooner the better. I don’t think I’m meant to spend the rest of my life as a farmer. You’ve already found your path, you old fogey, and I’m glad for you. I don’t have that yet.”

For a moment silence fell. It was an end and a beginning. They always had known it might come to this, but hoped it never would.

“You’ll come back to us, won’t you?” Mortimer asked her.

“Of course I will.”

***

It had been a long struggle across shifting sands, chilled and buffeted by the wind. Her mouth was full of grit and her paws stinging from the many tiny cuts left by jagged rocks and sharp blades of spiky sea grass. She was hungry and thirsty and weary to the bone.

But at last, after weeks of travel, the great mountain was in her sights.

A military hare in a buff-colored coat was waiting her at its base; curiously, he seemed to have been expecting her for some time. He swept off his jaunty feathered hat and made a low bow, to which she responded in kind.

“Is this Salamandastron, the mountain of the fire lizard?”

“The very place! And surely you must be the charming Lady Constance, daughter of Iris and Birchstripe, grand-niece to Lord Oakpaw the Valiant, eh wot! By the left! My pater’s pater served under your great uncle!”

“Just Constance, thank you,” she replied firmly, shaking his paw with a grip that made him wince.

“Just Constance, what an odd moniker! Right-o, I’ll give you the full tour. Please to jolly well follow me, madam!”

He led her upwards through a warren of stone corridors, grey and bleak, but fresh with bracing sea air and the tangy smell of salt and seaweed. He was chattering all the way.

“This, dear gel, is the ancestral home of badgers such as your good self, although it’s a few seasons since our valiant Lord went off questing after some wicked corsairs to the south—vile creatures, nasty tatty rats, all of ’em, need a lesson in cold steel. And so but a few of us gallant and handsome hares, such as myself, the humble Corporal Merriwether, remain here, guardin’ his domicile while he’s away, keep the home fires lit, so to speak. I’ll show you the common areas, dormitories and kitchens of course, the forge room, the terrace gardens, perchance even the entrance to the sacred jolly hall of badgers itself…but here’s the ticket, just the place to start. The mess hall!”

As they approached Constance could hear a commotion – at first what she thought was the sound of several creatures shouting, but then recognized as one creature doing three or four different voices, as the mood suited him. Corporal Merriwether sighed.

“That’ll be one of our new recruits. My apologies for the disturbance, marm.”

They rounded the corner and found themselves abruptly in the Salamandastron dining hall: brightly lit by westward-facing windows, with a crackling fire along one wall and long wooden tables and benches arranged in the center of the room. A slightly bucktoothed grey hare in regimental red was leaping and bounding from table to table, his long ears flopping comically about as he berated his lunching comrades, each of whom ignored him steadfastly. Constance had never in her life seen a creature behaving in such an outrageous manner.

“Cowards! Bounders! Fiends! Yah boo, ya rotters, I can outscoff any three of you with my paws behind me back, so there!”

“Steady in the ranks there! What’s all this about, you young terror?” barked the Corporal. The mad hare came smartly to attention and threw him a swift salute.

“Sah! Was simply interested in a little pie-scoffin’ competition, sah! First beast to finish their pie jolly well wins, sah!”

“You ’orrible animal, what on earth for?”

“Simply a spirit-raisin’ game, sah, fun for the troops, good for the morale, eh wot!”

“I could eat,” said Constance mildly, to general surprise. Several of the Long Patrol hares instinctively stood upon seeing the badger in their midst, and the red-coated hare made an elegant leg.

“By Jove! Honored to have such a worthy opponent, I’m sure! May we commence with the challenge, sah?”

The Corporal looked doubtful, but turned on his heel to shout in the direction of the kitchens.

“Oh, dash it all, if the badger Lady wants to humor the lower orders…Cook! A mushroom ’n’ tater pie for the young badgermiss, wot!”

Constance took a seat on a comfortable bench across from her challenger, who sat poised with wooden fork and knife hovering over a massive golden-crusted pie. In a twinkling a stout hare came hurrying over to place before her a pie of similar size, tugging respectfully at one of his ears.

“With the compliments of me goodself, Cook an’ Colonel Puffscut, marm. Rules for a Long Patrol scoffin’ competition are simple: on the count of three, start eatin’. First beast to finish their plate’s the winnah. One…two…three!”

Without further ado the hare across the table began shoveling down forkfuls of pie, gravy dripping from the corners of his mouth. All eyes were on Constance, who in turn was watching her challenger with great amusement. She waited until he had almost finished his portion before locking eyes with him, opening her massive jaws, and wedging the entire pie into her mouth. After three leisurely chews and a draught of nettle beer she swallowed and shrugged at him, wiping her paws fastidiously on a napkin.

“What was that you were saying about outscoffing three creatures at once?”

There was a smattering of applause from the Long Patrol hares, most of whom were glad to see their eccentric comrade taken down a peg.

“Good show, marm!” the strange creature cried sportingly, still covered in mushroom gravy, as he extended a paw for her to shake. “The name’s Basil Stag Hare, doncha know. I think we two fellow faminechops would make awfully good pals!”

“I certainly ’ope not,” the Corporal remarked despairingly to the Colonel. Constance had to hide a sudden grin.

She soon fit in at the mountain fortress: she was a badger in her prime. The hares kitted her up with a runner’s pack and sling, and she took to galloping alongside the patrols in daylight, telling jokes and gulping nutbrown ale by firesides at night. She spent hours in the forge room, smashing metal into arrowheads and sword blades, although she still preferred a simple javelin or the strength of her own limbs above all else. Basil, the renowned, if ridiculous, fur ’n’ foot fighter, taught her to box, a pursuit in which she excelled. A single right cross from one of her massive paws was enough to lay low a ferret or stoat (or once, by accident, an unprepared Lieutenant Swiftscut) for half a season.

A few of her most impressive feats became the stuff of legends in later days, such as the time when Basil convinced her to skip kitchen duty for an unauthorized day of leisure on the shore. It was a baking-hot summer’s morn, and they had unbelted their weapons so that they could swim in the cool green sea. They then sat wolfing down purloined fruit salad and honeyed damson tartlets, using a massive chunk of driftwood – perhaps the wreckage of a lost corsair ship – as a table. It was the badger who heard the approaching pawsteps first, and turned to see two weasels and a fox trying to sneak towards them, toying with their bladehilts.

“I say, chaps,” Basil said, feigning indignance. “This is a private party, d’you mind?”

“Shaddup, rabbit!” snarled the fox. “Don’t try to go fer yer weapons, they’re too far. Wot kind of vittles have ye got there?”

“Oh, a smidgen of this, a smidgen of that. ’Fraid there’s not enough left to share.”

“I’ll be the judge of that. Hand ’em over, or I’ll gut ye!”

With eye-blurring speed the fox drew his rusted cutlass and slashed at the air a hairsbreadth in front of Basil. The hare sidestepped and moved swiftly to stop him, but Constance was faster. With a mighty heave and a sky-shattering roar she levered their picnic table out of the sand, sending food flying and swinging the heavy spar in one fluid motion in the direction of their assailants.

“Blood ’n’ vinegarrrrr!”

CRACK!

All three vermin were knocked poleaxed to the ground, stricken completely senseless. Constance tossed the spar aside with a snort of satisfaction, only to see Basil dancing about on the sand about like a madbeast.

“What’s the matter? Are you wounded?” she demanded, but the hare was merely overcome with awe.

“Absoballylutely spiffin’, wot! Strewth, I’ve never seen anything like it!”

“Well, I thought I heard him ask you to pass the damson tartlet,” she said modestly.

Then there was another incident that aroused much mess-hall gossip later, not all of it friendly. Corporal Merriwether, driven half mad after several seasons’ of Basil and the badger’s endless capacity for trouble, had allowed the pair of them out on a weeklong patrol, accompanied by two companions. They were a few days’ journey from Salamandastron, in the last hours of their assigned mission, when a runner named Gurdee spotted a shabby lean-to built precariously against the cliffs. A mangy grey and white rat was crouched outside at a feeble fire. He did not appear to be armed, but Gurdee’s fellow runner, a hare named Bayberry, was taking no chances.

“Paws where we can see ’em, laddie buck! Just what d’ye think you’re doing on these shores?”

“Tryin’ to keep warm,” the rat said dully.

“Wouldn’t happen to be one of Zivka Bluesnout’s scummy corsairs, would you?”

“A deserter, probably,” Basil suggested, in a voice that seemed to propose moderation, but the rat made no reply, and Bayberry ground his teeth together at the slight. With a nod to Gurdee the pair of them drew their rapiers, perhaps seeking to intimidate him into an answer. Bayberry cut the ropes holding together the rat’s dilapidated tent, and Gurdee stirred up the seacoal with the point of his sword, extinguishing the last frail sparks of the fire.

“Stay mum if you wish, but we can’t have questionable characters campin’ out on our Badgerlord’s territory. You’ll need to clear out by nightfall.”

The rat had not made one move to stop this destruction, but instead sat watching listlessly from the sand, one grubby paw splayed protectively over a deep wound in his foreleg. When she saw it Constance barked out a sharp order, her voice echoing off of the cliff walls like a thunderclap.

“Hares, leave that creature alone!”

Obediently they froze, but there was surprise and perhaps even slight resentment in their eyes. Constance ignored them and turned her attention back to the rat.

“How did you injure your leg?”

“Slipped,” he said hollowly. “On the sea rocks, foragin’ the tide pools.”

“When?”

“Few days ago.”

Constance tugged her haversack from her shoulders and began rummaging through it, coming up with a clean strip of bandage and pawful of pungent leaves and mosses.

“Clean the wound in sea water, and then bind it with these herbs. It may sting, but it’ll heal. In the meantime, you’ll want to stay off it as much as you can. Do you have enough food here to last you a day or two?”

The rat shook his head. Constance dug through the haversack again and then set the last of her field rations, a strong wheat loaf and some good mountain cheese, atop the empty cask that served him as a table.

“Take these and move once when you’ve had time to rest. We’re sorry to have bothered you.”

Then without waiting for a word of thanks she turned on her heel and marched away from the scene, accompanied swiftly by Basil. Gurdee and Bayberry sheathed their blades with a last warning look at the rat before jogging to the badger’s side. They disapproved and did not try to disguise it.

“Not entirely sure I understand you, marm, givin’ away healing medsuns like that to a rat, of all creatures.”

“Rather, wot! An’ beggin’ your pardon, but it sticks in my gizzard to see proper gentlebeasts’ tucker wasted on a villain like that!”

Basil, seeing the strange look in her eyes, was the only one who remained silent. Constance continued to stride ahead at a purposeful double-march.

On the journey back to Salamandastron she seemed somehow a changed creature, moody and withdrawn. She no longer hungered after battle and danger the way the young hares did. Even the ballads and marching songs, rousing tales of glory and peril and heroism, had lost their charm. She trusted only Basil for counsel, sitting up to talk with him late into the night.

She missed the new green of oak leaves in the woodlands, the ruddy rose of sandstone in the setting sun, the stillness and sweet fragrance of the Abbey orchards. She missed a gentle, kindly mouse in the habit of his Order, cooling his footpaws with her on the banks of the River Moss.

One morning she left the mountain behind and went home to Mossflower Country.

***

She could hear the ringing of the Joseph Bell even from a distance, clear and strong and exultant, and almost in spite of herself began to run, paws churning up the pathsoil. Through the lacework of budding beech and elm leaves she soon saw flashes of pink stone, and then she found herself before the gate. She had to pause for a moment to catch her breath and calm her emotions. She had dreamed of this moment every evening of her journey back; perhaps she would wake up to find that this too had been nothing but her imagination.

Then she stepped forward and rapped at the door.

After a few moments a chubby little dormouse heaved the doors open, peeking cautiously around the corner. At the sight of her his mouth fell open, and he nearly dropped his bunch of gatekeys in surprise.

“May a weary traveler enter?”

“Heavens above!” the dormouse said breathlessly. “You must be that badger our Abbot talks about so much! Come inside, come inside and rest yourself. My name is Brother Abel. I think I remember you from a midsummer’s feast.”

No sooner had the gatekeeper let her into the Abbey grounds than another mouse materialized as if from thin air. Before she could say a word he flung his paws around her, laughing and weeping all at once.

“Constance! Constance!”

“Mortimer!”

“Constance, my dear, dear friend!”

Mortimer was a young mouse still, but his fur was already taking on a tinge of silvery grey. His face was alight with joy. He stepped back to get a better look at her, awed by her obvious strength and size.

“You’re as tall as an oak! Where have you been all these long seasons?”

“You’re the same height as you always were. I’ve been traveling, like I said I would.”

“You must tell me all about it! Let’s go for a walk in the cloister gardens. Thank you, Brother Abel, you can close the gate.”

Brother Abel made a respectful bow, a gesture which surprised Constance. But she soon forgot about it as she related to Mortimer the story of her travels. For what felt like hours she told him of the mountain and the great gray-green sea, the hares she had befriended and the dangers she had faced. With every step they took through the familiar gardens, every time Mortimer laughed at a funny story or gasped at a tale of a narrow victory over vicious foebeasts, her heart felt a little lighter.

“Well, that’s about it,” she finished at last, wanting to hear about what he’d been doing all this time. “I’ve had plenty of adventure, like I wanted to. And now I don’t know what to do.”

“So does this mean you’re here to stay?” he asked hopefully. Constance let out a sigh.

“Oh, I don’t know. Does Abbot Cedric have a use for a large, grouchy badger like me?”

“Good old Abbot Cedric. I’m sure he would have, but he went to his rest two seasons ago, I’m afraid.”

“I’m sorry, Mortimer. I know you were close to him.”

“He was a wise and compassionate soul. I hope I am serving well in his stead.”

“What do you mean?” asked Constance. Then, suddenly, she understood Brother Abel’s bow. Mortimer seemed to draw himself up a little, a creature fulfilled and fully at peace.

“Just before Abbot Cedric passed on, he told me that he’d decided to leave Redwall Abbey and all its creatures in my care. I am Abbot Mortimer now.”

Constance was still grappling with this news when she felt somebeast step on her footpaw. A mousebabe and a small squirrel, both clad in the linen smocks of Abbey young ones, had attached themselves to the hem of her tunic, tugging and pushing. They were addressing her in what they imagined was their best imitation of a badgers’ voice, trying to make themselves sound gruff and fearsome.

“I’mma bigga strong badger, make you falla down!”

“We’re not scareded of anybeast!”

Constance was not used to little ones, but she felt her heart soften. With a wink to Mortimer she scooped the pair of them up single-pawed, tumbling dramatically into a patch of clover and coming to rest with a bump.

“Phew, what fierce warriors! You’ve slain me, you little rogues!”

“Yee hee! Again! Again again again!”

“These little scallawags are Holly and Jessamine, two of our most ferocious Dibbuns,” Mortimer said, smiling. Constance looked aghast.

“Dibbuns? What in the world is that?”

“It’s what we call the young ones here at Redwall.”

“Nonsense. I’ve never heard something so ridiculous.”

“Again again again!” interrupted the squirrelbabe Jessamine, trying to clamber up onto Constance’s head. Constance struggled to her feet in mock exhaustion and bent to take each of them by the paw.

“How about you two ruffians show me and Mor – the Father Abbot to the kitchens first? I’m famished!”

“What does badgers likes to eat?” Holly demanded.

“Naughty little mice and squirrels!” Constance said, raising her eyebrows and showing off her shining canine teeth.

“No!” shrieked Holly in terrified delight, while Jessamine giggled. “They likes chesknutters an’ strawbee cordial!”

“Oh, that’s right! I forgot. I bet you like chestnuts and strawberry cordial too. Here, let’s wash our paws off in the pond first.”

“I think we may have a use for a large, grouchy badger after all,” said Mortimer, with proper Father Abbot-like sobriety.

She did not go back to the cottage where she had grown up. Mortimer had tended it for her while she was away, but she felt that with a new chapter of her life should come new lodgings, and had him find a family of poor fieldmice to live there instead. Nights she slept out on the soft grass of the Abbey lawn, waking up drenched in dew. In the early mornings, recalling her Salamandastron routine, she let herself out through the side gate and took long rambles through Mossflower Wood, running, swimming, testing her strength against heavy boulders, practicing with spears, javelins and her grandfather’s longbow, which she kept stored in a mossy log, away from Mortimer’s slightly rueful glances and the peaceful Redwallers’ fearful ones.

But she was always back at the Abbey before luncheon, helping with chores and, mostly, keeping a weather eye on the mischievous young ones, who soon began to call her “Muvver Constance,” just as the grown-ups respectfully referred to her as “the Badgermum.” She had an unexpected gift for caring for the Abbeybabes, and eventually she knew she wouldn’t dream of doing anything else. She traded her woodland homespun for an apron and stout gown, with deep pockets to hold clean handkerchiefs and found toys and coltsfoot pastilles. At mealtimes she could often be found sitting at the young ones’ table, spoon-feeding the smallest of the babes, convincing middle-aged ones to eat their turnips and rutabagas, cuddling and rocking fractious infants to sleep while their older siblings perched on her shoulders. At bedtime she tucked the little ones in, one by one, and hummed old badgerwives’ lullabies or related Martin-the-Warrior legends until the dormitories echoed with the sound of gentle snoring.

Mortimer’s heart gladdened the first time she spoke of Redwall as home.

***

Constance was several seasons his elder, but it was Mortimer who grew old and fragile first. His eyesight grew blurry, necessitating a pair of crystal spectacles. In the winters, when the orchard trees were brown and brittle, and the Abbey grounds sparkled white with snow, his joints sometimes grew stiff and painful. But untiringly he watched over his beloved Redwall, through many peaceful years, as any good Father should: patient, wise, just, kind, with the badger as his strong right paw.

Then came the seasons of Cluny the Scourge.

In the seconds before she picked up the Cavern Hall table and threatened to smash it over the warlord’s head, she chanced a glance at her friend and saw on his face an expression she’d never seen there before: rage.

In the days afterwards, as Martin was lost to the enemy, as creatures were wounded and killed, this was soon followed by another first, one that startled her even more: uncertainty.

Constance was bleeding freely from some half a dozen gashes along her flanks and on her paws, wounds earned during a vicious skirmish with several of Cluny’s scouts. Abbot Mortimer worked by candlelight to clean the deep cuts and treat them with herbs. He was unusually silent, not speaking until his work was finished.

“Please try to take better care of yourself, Constance,” he said at last, rather shortly. “You put yourself in danger far too often.”

“I only do what I must, Father Abbot.”

“But if something were to happen to you –”

“You have Matthias and Basil, Jess and Winifred. Redwall would survive.”

“I am asking you as a friend,” said Abbot Mortimer. “My dearest and wisest friend. If we win this war tomorrow it will already have been at too great a price. Do not ask me to suffer your loss on top of everything that has already come to pass.”

Constance was stunned by the emotion in his voice. After a moment she laid a heavy paw on his shoulder.

“I’m sorry to have upset you, Abbot. I’ll try my best.”

It would never have occurred to her to ask him the same. He was as ever the careful, noncombatant Mortimer, a healer and a stretcher-bearer, a creature of peace, and the battle would never breach the Abbey walls to reach him. She would see to it.

The Father Abbot was awakened by a sword-point at his throat.

The poison barb on Cluny’s tail had done its deadly work. The Father Abbot was dying.

***

There was much work to be done, after the war ended, but for a while she thought again of flight. Of sandy windswept shores and austere halls of mountain stone. Of the borderlands, of the northlands. Even of the sea. Anywhere but here, where the crimson laterose was still in fragrant bloom, and the big carved chair at the head of Great Hall sat empty, and the verdant gardens were full of mice in wide-sleeved brown robes gathering berries and talking with the Sparra, but none of them was Mortimer.

Yet every time she decided that the wound was just too deep, that she’d go mad with grief if she didn’t get away from here, something – or someone – changed her mind.

Matthias, still victory-stunned: “Constance, what should we do about the Joseph Bell?”

Mordalfus, solemn and deferential: “Constance, where do you think we should house the Guosim warriors who’d like to stay here till the springtide?”

The Redwallers at large, surprising her in Cavern Hole one day with a badger-sized marchpane cake: “Hurrah for Constance! We’d have been lost without you.”

And the young ones, clinging to her apron: “Muvver Constance, don’t be sad.”

*****************************************

Slowly summer gave way to autumn, autumn to winter, and winter to a spring whose beauty was beyond compare. John Churchmouse had suggested a season-name upon which they had all agreed.

It was the Springtide of the Warriors’ Wedding!

Constance had spent the preceding week tugging a hay cart far and wide through Mossflower Wood, ferrying creatures to the Abbey for the ceremony that would take place today. Now the Sisters of the order and all her woodland friends had spirited Cornflower away to the dormitories to dress her in cream-colored gown and veil, and Matthias was waiting anxiously in the gatehouse that would become their home, with Log-a-Log and Basil fussing over his tunic, to which he had tied a certain flowered headband that a certain maiden had bestowed upon him, what felt like years ago.

Therefore, Constance was enjoying a rare moment of rest out on the sunwarmed steps overlooking the orchards, as the blossoms danced and the pond rippled gently in a playful breeze. It reminded her of something Mortimer had said.

I have seen it all before, many times, and yet I never cease to wonder. Life is good, my friends. I leave it to you...

In the kitchens Friar Hugo was making a trifle as tall as two mice, heaping with raspberries, meadowcream, and honey-soaked sponge. Foremole and his crew were filling Great Hall and Cavern Hole with bunches of purple irises, butter-colored daffodils and, of course, cerulean-blue cornflower, while Winifred and her otters lined the cloisters and outside corridors with sweet alyssum and pale pink and white water lilies. Ambrose Spike was shepherding a herd of little ones as they rolled barrels of strawberry fizz, October ale and dandelion-burdock cup to the tables out under the shade. Jess Squirrel and Silent Sam were leaping bough to bough amongst the fruit trees, affixing colored lanterns to the branches.

The friends I know and love are all about me.

Constance remembered another feastday many seasons ago, and a wise young mouse marveling with her at the splendor of the Abbey and the goodness of its creatures, and she felt, for the first time in long memory, entirely at peace.

“Today is a good day, my old friend,” the badger said.

#Redwall#Constance#Abbot Mortimer#Redwall fic#Redwall fanfiction#the ending is kinda maximum cheese#BUT I REALLY HOPE YOU LIKE IT AAA#it was so hard trying to keep this a secret while writing it!#fluff#angst#whatever you would call this#with a title shamelessly stolen from Mr. Jacques himself

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

URL song titles meme

tagged by @dreamerinsilico - thanks so much!!

Spell your URL with song titles: (you’re all so lucky I didn’t just fling the worst of eurovision at you this is very very long)

S - Stockton Gala Days - 10,000 Maniacs

T - This Time - Monika Linkytė & Vaidas Baumila

Y - Yon Ferrets Return - Neko Case

L - Letter to John Shriner - Jason Webley

I - I Like a Boy in Uniform - The Pipettes

S - Still Catch the Tide - Seanan McGuire

H - Hollywood - Jukebox the Ghost

A - After All - Dar Williams

N - Nobody’s Crying - Patty Griffin

A - All is Well (Goodbye, Goodbye) - Radical Face

C - The Creation of Man - The Scarlet Pimpernel

H - The Horror of Our Love - Ludo

R - Rivers Run - Karine Polwart

O - Oh, Death! - Pearl and the Beard

N - No Rest for the Wicked - A Hawk & A Hacksaw

I - I Was Born for This - Austin Wintory

S - The Seventh Girl - Bella Hardy

M - Meow! (The Cat Duet) - Attributed to Rossini, actual author unclear

Tagging @thebluestofdaisies, @violetutterances, @sweetdreamr, @ladynorbert, gdi you all have long urls I’m sorry, and anybody else who wants to do this and feels I’ve forgotten them

#meme things#ilu babe but ffs#there are twenty three letters in my url this is a solid if terrible playlist just as it is#there's only one broadway song and one eurovision song you're welcome#rossini's cat duet has like eight official names and that's the worst one but it also serves my purposes#also I am v tired and need to be up in like five hours to open god help me

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

"...yes?!?! How would it not mean that when he looked like you!!"

"I don't know, maybe you meant he looked like me but better!"

#ic#goingtosave#v: yon ferrets return#your asks answered#scott im sorry to say#you are dating a moron

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

"It's not as hot as a sword! Come on, man, don't do this again..."

"You're right, it's hotter than a sword! By like, definition!"

1 note

·

View note

Note

"...That's less hot."

"What?!"

1 note

·

View note

Note

"I don't even know what to say to you, you jerk! I was definitely calling you hot and maybe thinking of finding a realistic looking fake sword for you, that's all!"

"Okay, but, if you're gonna do that, why not a lightsaber?"

1 note

·

View note

Note

"Are you actually saying these words!?"

"I feel like it should be obvious that I've completely lost control of what's coming out of my mouth!"

1 note

·

View note

Note

"...Which would obviously imply that you are also hot?!?"

"Does it, though?!"

1 note

·

View note

Note

"What is wrong with you?? I just said he looked like you!"

"Yeah, but you also said he's hot!"

1 note

·

View note

Note

1 note

·

View note

Note

"Oh my god I just meant there was a hot guy with a sword I saw!"

"Now this guy is hot?!"

1 note

·

View note