#wounded knee

Text

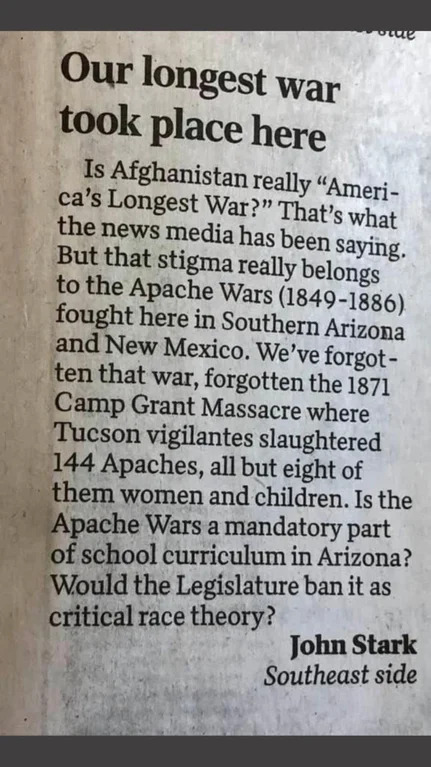

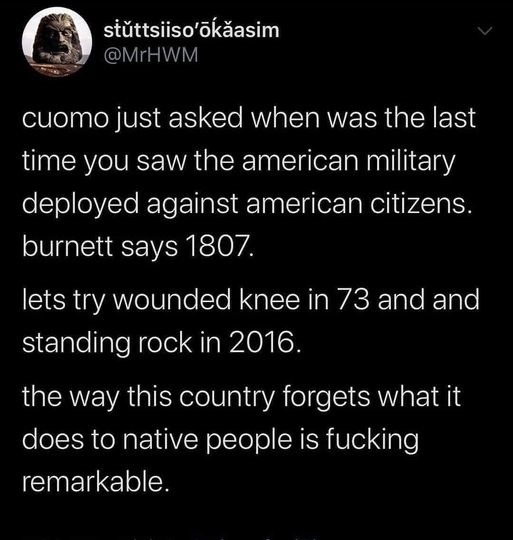

#letter to the editor#newspaper clipping#twitterature#sṫǔttsiiso'ōḱăasim#Native American#war#Wounded Knee#Standing Rock#John Stark

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

The 50th anniversary of AIMs (American Indian Movement's) occupation at Wounded Knee is coming up, so the Lakota People's Law Project is leading another push to free an AIM activist who was wrongly convicted of killing two federal agents in 1975- Leonard Peltier. He was convicted on false evidence and false testimony and sentenced to two life sentences. He is now 78.

LPL has a formatted email up on their website now which you can personalize and send to Biden to ask for clemency. (Please personalize emails like this so it doesn't get filtered as spam. Just move some words around, add some, take some, you don't have to write a whole email.) Please pass this around.

#leonard peltier#aim#american indian movement#leonard peltier defense committee#wounded knee#protest#occupation#political prisoners#petition#president biden#clemency#action#lakota#ojibwe#advocacy#native rights#indigenous people#legal action#federal prison#indian boarding schools#boarding school#history#bishop desmond tutu#nelson mandela#dalai lama#chase iron eyes#legal defense#activists

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

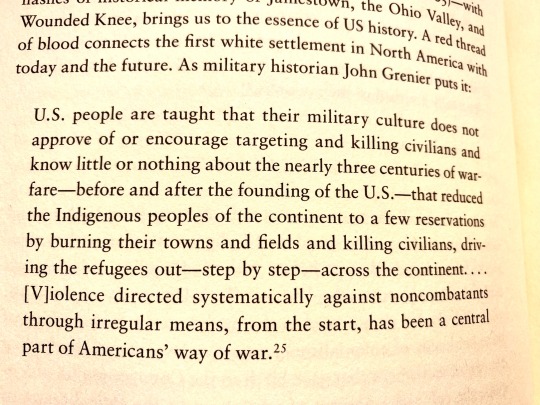

“U.S. people are taught that their military culture does not approve of or encourage targeting and killing civilians and know little or nothing about the nearly three centuries of war-fare-before and after the founding of the U.S.-that reduced the Indigenous peoples of the continent to a few reservations by burning their towns and fields and killing civilians, driving the refugees out--step by step--across the continent....Violence directed systematically against noncombatants through irregular means, from the start, has been a central part of Americans' way of war. “

Military Historian John Grenier

#us history#wounded knee#sand creek#trail of tears#the long walk#bear river#thanks taking#in Country#🇺🇸#land back#crazy horse#tecumseh#sitting bull#Geronimo#chief joseph#emiliano zapata#Joaquin murrieta#Pó Pay#captain Jack#war crimes

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Stephen Millies

On Sept. 12, Leonard Peltier turned 79 years old in a maximum security federal prison in Coleman, Florida. He has spent over 47 years being locked up for being a leader of AIM — the American Indian Movement.

That’s 20 years longer than the time the old apartheid regime in South Africa imprisoned Nelson Mandela. The late President Mandela sought Leonard Peltier’s freedom.

So have people around the world. Thirty-five people were arrested at the White House on Sept. 12, demanding the Indigenous political prisoner’s release.

Leonard Peltier is being kept locked up in revenge for the historic 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, by AIM members and supporters in 1973. That’s where 300 children, women, and men from the Lakota Nation were slaughtered by the U.S. army in 1890.

#Leonard Peltier#FreeLeonardPeltier#political prisoners#FBI#Wounded Knee#AIM#repression#Indigenous#protest#Joe Biden#arrests#Struggle La Lucha

60 notes

·

View notes

Link

Kalle Banaille - Indian Country Today

Legacy of Wounded Knee occupation lives on 50 years later

The occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, began 50 years ago and was one in a string of protests from 1969 to 1973 that pushed the American Indian Movement to the forefront of Native activism

WOUNDED KNEE, S.D. (AP) — Madonna Thunder Hawk remembers the firefights.

As a medic during the occupation of Wounded Knee in early 1973, Thunder Hawk was stationed nightly in a frontline bunker in the combat zone between Native American activists and U.S. government agents in South Dakota.

“I would crawl out there every night, and we’d just be out there in case anybody got hit,” said Thunder Hawk, of the Oohenumpa band of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, one of four women assigned to the bunkers.

Memories of the Wounded Knee occupation — one in a string of protests from 1969 to 1973 that pushed the American Indian Movement to the forefront of Native activism — still run deep within people like Thunder Hawk who were there.

Thunder Hawk, now 83, is careful about what she says today about AIM and the occupation, but she can’t forget that tribal elders in 1973 had been raised by grandparents who still remembered the 1890 slaughter of hundreds of Lakota people at Wounded Knee by U.S. soldiers.

“That’s how close we are to our history,” she told ICT recently. “So anything that goes on, anything we do, even today with the land-back issue, all of that is just a continuation. It’s nothing new.”

Other feelings linger, too, over the tensions that emerged in Lakota communities after Wounded Knee and the virtual destruction of the small community. Many still don’t want to talk about it.

But the legacy of activism lives on among those who have followed in their footsteps, including the new generations of Native people who turned out at Standing Rock beginning in 2016 for the pipeline protests.

“For me, it’s important to acknowledge the generation before us — to acknowledge their risk,” said Nick Tilsen, founder of NDN Collective and a leader in the Standing Rock protests, whose parents were AIM activists. “It’s important for us to honor them. It’s important for us to thank them.”

Akim D. Reinhardt, who wrote the book, “Ruling Pine Ridge: Oglala Lakota Politics from the IRA to Wounded Knee,” said the AIM protests had powerful social and cultural impacts.

“Collectively, they helped establish a sense of the permanence of Red Power in much the way that Black Power had for African Americans, a permanent legacy,” said Reinhardt, a history professor at Towson University in Towson, Maryland.

“It was the cultural legacy that racism isn’t OK and people don’t need to be quiet and accept it anymore,” he said. “That it’s OK to be proud of who you are.”

A series of events in South Dakota in recent days recognized the 50th anniversary of the occupation, including powwows, a documentary film showing and a special honor for the women of Wounded Knee.

‘‘THUNDERBOLT’ OF PROTEST

The occupation began on the night of Feb. 27, 1973, when a group of warriors led by Oklahoma AIM leader Carter Camp, who was Ponca, moved into the small town of Wounded Knee. The group took over the trading post and established a base of operations along with AIM leaders Russell Means, of the Oglala Sioux Tribe; Dennis Banks, who was Ojibwe; and Clyde Bellecourt, of the White Earth Nation.

Within days, hundreds of activists had joined them for what became a 71-day standoff with the U.S. government and other law enforcement.

It was the fourth protest in as many years for AIM. The organization formed in the late 1960s and drew international attention with the occupation of Alcatraz in the San Francisco Bay from 1969-1971. In 1972, the Trail of Broken Treaties brought a cross-country caravan of hundreds of Indigenous activists to Washington, D.C., where they occupied the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters for six days.

Then, on Feb. 6, 1973, AIM members and others gathered at the courthouse in Custer County, South Dakota, to protest the killing of Wesley Bad Heart Bull, who was Oglala Lakota, and the lenient sentences given to some perpetrators of violence against Native Americans. When they were denied access into the courthouse, the protest turned violent, with the burning of the local chamber of commerce and other buildings.

Three weeks later, AIM leaders took over Wounded Knee.

“It had been waiting to happen for generations,” said Kevin McKiernan, who covered the Wounded Knee occupation as a journalist in his late 20s and who later directed the 2019 documentary film, “From Wounded Knee to Standing Rock.”

“If you look at it as a storm, the storm had been building through abuse, land theft, genocide, religious intoleration, for generations and generations,” he said. “The storm built up, and built up and built up. The American Indian Movement was simply the thunderbolt.”

The takeover at Wounded Knee grew out of a dispute with Oglala Sioux tribal leader Richard Wilson but also put a spotlight on demands that the U.S. government uphold its treaty obligations to the Lakota people.

By March 8, the occupation leaders had declared the Wounded Knee territory to be the Independent Oglala Nation, granting citizenship papers to those who wanted them and demanding recognition as a sovereign nation.

The standoff was often violent, and supplies became scarce within the occupied territory as the U.S. government worked to cut off support for those behind the lines. Discussions were ongoing throughout much of the occupation, with several government officials working with AIM leaders to try and resolve the issues.

The siege finally ended on May 8 with an agreement to disarm and to further discuss the treaty obligations. By then, at least three people had been killed and more than a dozen wounded, according to reports.

Two Native men died. Frank Clearwater, identified as Cherokee and Apache, was shot on April 17, 1973, and died eight days later. Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, who was Oglala Lakota, was shot and killed on April 26, 1973.

Another man, Black activist Ray Robinson, who had been working with the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization, went missing during the siege. The FBI confirmed in 2014 that he had died at Wounded Knee, but his body was never recovered. A U.S. marshal who was shot and paralyzed died many years later.

Camp was later convicted of abducting and beating four postal inspectors during the occupation and served three years in federal prison. Banks and Means were indicted on charges related to the events, but their cases were dismissed by a federal court for prosecutorial misconduct.

Today, the Wounded Knee National Historic Landmark identifies the site of the 1890 massacre, most of which is now under joint ownership of the Oglala Sioux and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes.

The tribes agreed in 2022 to purchase 40 acres that included the area where most of the carnage took place in 1890, the ravine where victims fled and the area where the trading post was located.

The purchase, from a descendant of the original owners of the trading post, included a covenant requiring the land to be preserved as a sacred site and memorial without commercial development.

And though internal tensions emerged in the AIM organization in the years after the Wounded Knee occupation, AIM continues to operate throughout the U.S. in tribal communities and urban areas.

In recent years, members participated in the Standing Rock protests and have persisted in pushing for the release from prison of former AIM leader Leonard Peltier, who was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder despite inconsistencies in the evidence in the deaths of two FBI agents during a shootout in 1975 on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

A NEW GENERATION

Tilsen, now president and chief executive of NDN Collective, an Indigenous-led organization centered around building Indigenous power, traces the roots of his activism to Wounded Knee.

His parents, JoAnn Tall and Mark Tilsen, met at Wounded Knee, and he praises the women of the movement who sustained the traditional matriarchal system during the occupation.

“I grew up in the American Indian Movement,” said Tilsen, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation. “It wasn’t a question about what you were fighting for. You were raised up in it. In fact, if you didn’t fight, you weren’t going to live.”

Tilsen credits AIM and others for most of the rights Native Americans have today, including the ability to operate casinos and tribal colleges, enter into contracts with the federal government to oversee schools and other services, and religious freedom.

He said the movement showed the world that tribes were sovereign nations and their treaties were being violated. And when AIM and spiritual leaders such as Henry Crow Dog, Leonard Crow Dog and Matthew King joined the fight, it became intergenerational.

“It became a spiritual revolution,” he said. “It also became a fight that was about human rights. It became a fight that was about where Indigenous people aren’t just within the political system of America, but within the broader context of the system; of the world.”

Tilsen appreciates that his parents were willing to participate in an armed revolution to achieve one of their dreams of establishing KILI radio station, known as the “Voice of the Lakota Nation,” which began operating in 1983 as the first Indigenous-owned radio station in the United States.

The Dakota Access Pipeline protest in 2016 became a defining moment for him and his brother. They had wondered, he said, what would be their Wounded Knee?

“What made it so powerful and what made it different was that you actually had grassroots organizers and revolutionaries and official tribal governments coming together, too,” Tilsen said. “I think that Standing Rock in particular actually reached way further than Wounded Knee because of how the issue was framed around ‘water is life.’”

Alex Fire Thunder, deputy director of the Lakota Language Consortium, said the occupation of Wounded Knee and other activism helped revitalize Indigenous languages and cultures. His mother was too young to have participated in the occupation but he said she remembered visits from AIM members in the community.

“The whole point of AIM, the American Indian Movement, was to bring back a sense of pride in our culture,” Fire Thunder, Oglala Lakota, told ICT.

FUTURE GENERATIONS

For Thunder Hawk, the issues became her lifelong work rather than momentary activism.

She joined AIM in 1968 and participated in the occupation at Alcatraz, the BIA headquarters, the Custer County Courthouse and Wounded Knee, as well as the Standing Rock pipeline protest in 2016.

She said work being done today by a new generation is a continuation of the work her ancestors did.

“That’s why we were successful in Indian Country, because we were a movement of families,” she said. “It wasn’t just an age group, a bunch of young people carrying on.”

She hopes her legacy will live on, that her great-great-grandchildren will see not just a photo of her but know what she sounded like and the person she seemed to be.

It’s something that she can’t have when she looks at a photo of her paternal great-grandparents.

“Hopefully that’s what my descendants will see, you know?” she said. “And with the technology nowadays, they can press a button, maybe, and it’ll come up.”

Frank Star Comes Out, the current president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, also believes it’s time for the previous generation’s work to be recognized.

Some of his family members strongly supported AIM, including his mother and father. He said it’s important to fight for his people, who survived genocide.

“That’s why I support AIM, not only on a family level,” he said. “I have a lot of pride in who I am as a Lakota. … Times (have) changed. Now I’m using my leadership to help our people rise, to give them a voice. And I believe that’s important for Indian Country.”

Kalle Benallie - Indian Country Today, February 27th 2023

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

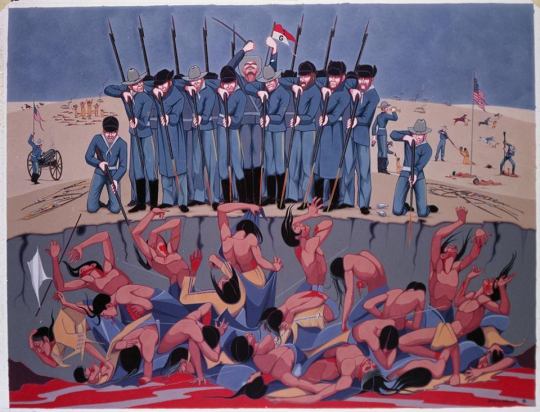

The Wounded Knee Massacre Dec 29, 1890

#wounded knee#1890#american history#native american history#wounded knee masacre#dakota#south dakota

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just realized that the 50th anniversary of the Wounded Knee Occupation started like a week ago. (Feb 27 - May 8, 1973) For 71 days, 200 Oglala Sioux and AIM activists occupied the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in opposition to the corruption of tribal chairman Richard Wilson and centuries of failure by the US Government to honor treaties with native peoples. The town would be besieged by federal forces (US Marshals, FBI, SD National Guard) and GOON (a paramilitary force run by Richard Wilson). 5 people were killed, and 16 wounded during the siege. On May 5, an agreement was reached between leaders of the occupiers and the feds. By May 8, the town had been evacuated, and the US Government seized control. The occupation saw significant public support and helped bring light to issues facing indigenous peoples within the US. Issues they continue to face and fight to this day, 50 years later. (For example, there are around 4200 to 5700 unsolved cases involving murdered or missing indigenous women, as of 2021)

#AIM#american indian movement#wounded knee#wounded knee 1890#wounded knee 1973#pine ridge reservation#indigenous history#american indian history#mmiw#missing and murdered indigenous women#american history#indigenous history is american history#land back#yes all of it

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never forgive Wounded Knee - Christofer Themptander - 1971

95 notes

·

View notes

Link

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

December 28, 2022

Heather Cox Richardson

On the clear, cold morning of December 29, 1890, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, three U.S. soldiers tried to wrench a valuable Winchester away from a young Lakota man. He refused to give up his hunting weapon. It was the only thing standing between his family and starvation and he had no faith it would be returned to him as the officer promised: he had watched as soldiers had marked other confiscated valuable weapons for themselves.

As the men struggled, the gun fired into the sky.

Before the echoes died, troops fired a volley that brought down half of the Lakota men and boys the soldiers had captured the night before, as well as a number of soldiers surrounding the Lakotas. The uninjured Lakota men attacked the soldiers with knives, guns they snatched from wounded soldiers, and their fists.

As the men fought hand to hand, the Lakota women who had been hitching their horses to wagons for the day’s travel tried to flee along the nearby road or up a dry ravine behind the camp. Stationed on a slight rise above the camp, soldiers turned rapid-fire mountain guns on them. Then, over the next two hours, troops on horseback hunted down and slaughtered all the Lakotas they could find: about 250 men, women, and children.

A dozen years ago, I wrote a book about the Wounded Knee Massacre, and what I learned still keeps me up at night. But it is not December 29 that haunts me.

What haunts me is the night of December 28.

On December 28 there was still time to avert the massacre.

In the early afternoon, the Lakota leader Big Foot—Sitanka—had urged his people to surrender to the soldiers looking for them. Sitanka was desperately ill with pneumonia, and the people in his band were hungry, underdressed, and exhausted. They were making their way south across South Dakota from their own reservation in the northern part of the state to the Pine Ridge Reservation. There they planned to take shelter with another famous Lakota chief, Red Cloud. His people had done as Sitanka asked, and the soldiers escorted the Lakotas to a camp on South Dakota's Wounded Knee Creek, inside the boundaries of the Pine Ridge Reservation.

For the soldiers, the surrender of Sitanka's band marked the end of what they called the Ghost Dance Uprising. It had been a tense month. Troops had pushed into the South Dakota reservations in November, prompting a band of terrified men who had embraced the Ghost Dance religion to gather their wives and children and ride out to the Badlands. But at long last, army officers and negotiators had convinced those Ghost Dancers to go back to Pine Ridge and turn themselves in to authorities before winter hit in earnest.

Sitanka’s people were not part of the Badlands group and, for the most part, were not Ghost Dancers. They had fled from their own northern reservation two weeks before when they learned that officers had murdered the great leader Sitting Bull in his own home. Army officers were anxious to find and corral Sitanka’s missing Lakotas before they carried the news that Sitting Bull had been killed to those who had taken refuge in the Badlands. Army leaders were certain the information would spook the Ghost Dancers and send them flying back to the Badlands. They were determined to make sure the two bands did not meet.

But South Dakota is a big state, and it was not until late in the afternoon of December 28 that the soldiers finally made contact with Sitanka's band. The encounter didn’t go quite as the officers planned: a group of soldiers were watering their horses in a stream when some of the traveling Lakotas surprised them. The Lakotas let the soldiers go, and the men promptly reported to their officers, who marched on the Lakotas as if they were going to war. Sitanka, who had always gotten along well with army officers, assured the commander that the band was on its way to Pine Ridge, and asked his men to surrender unconditionally. They did.

By this time, Sitanka was so ill he couldn't sit up and his nose was dripping blood. Soldiers lifted him into an army ambulance—an old wagon—for the trip to the Wounded Knee camp. His ragtag band followed behind. Once there, the soldiers gave the Lakotas an evening ration and lent army tents to those who wanted them. Then the soldiers settled into guarding the camp.

And the soldiers celebrated, for they were heroes of a great war, and it had been bloodless, and now, with the Lakotas’ surrender, they would be demobilized back to their home bases before the South Dakota winter closed in. As they celebrated, more and more troops poured in. It had been a long hunt across South Dakota for Sitanka and his band, and officers were determined the group would not escape them again. In came the Seventh Cavalry, whose men had not forgotten that their former leader George Armstrong Custer had been killed by a band of Lakota in 1876. In came three mountain guns, which the soldiers trained on the Indian encampment from a slight rise above the camp.

For their part, the Lakotas were frightened. If their surrender was welcome and they were going to go with the soldiers to Red Cloud at Pine Ridge, as they had planned all along, why were there so many soldiers, with so many guns?

On this day and hour in 1890, in the cold and dark of a South Dakota December night, there were soldiers drinking, singing and visiting with each other, and anxious Lakotas either talking to each other in low voices or trying to sleep. No one knew what the next day would bring, but no one expected what was going to happen.

One of the curses of history is that we cannot go back and change the course leading to disasters, no matter how much we might wish to. The past has its own terrible inevitability.

But it is never too late to change the future.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#History#Native American#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters From an American#Wounded Knee#Wounded Knee Massacre

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spotted Elk (Lakota: Uŋpȟáŋ Glešká, sometimes spelled OH-PONG-GE-LE-SKAH or Hupah Glešká: 1826 approx – December 29, 1890), was a chief of the Miniconjou, Lakota Sioux. He was a son of Miniconjou chief Lone Horn and became a chief upon his father's death. He was a highly renowned chief with skills in war and negotiations. A United States Army soldier, at Fort Bennett, coined the nickname Big Foot (Si Tȟáŋka) – not to be confused with Oglala Big Foot (also known as Ste Si Tȟáŋka and Chetan keah).

In 1890, he was killed by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (Chankwe Opi Wakpala, Wazí Aháŋhaŋ Oyáŋke), South Dakota, USA with at least 150 members of his tribe, in what became known as the Wounded Knee Massacre.

#Spotted Elk#Uŋpȟáŋ Glešká#Hupah Glešká#native american#Lakota Sioux#Miniconjou#Wounded Knee Massacre#Wounded Knee#XIX century#people#portrait#photo#photography#Black and White

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minerva Coirrine Bear Killer | Canku Luta Akan Mani Win

B. October 23rd 1958 in Allen, South Dakota

Minerva was Oglala Lakota. She was a seamstress and made countless star quilts. She worked as a cook for Anpetu Luta Otipi and had previously worked driving Elderly Meals Program van to deliver food to the elders.

Minerva served as Chairwoman of North Corn Creek community and took part in the Wounded Knee Occupation in 1973, frequently sharing memories of her joining the AIM.

Allen, South Dakota

#Minerva Coirrine Bear Killer#Canku Luta Akan Mani Win#Allen#Pine Ride Reservation#South Dakota#Oglala Lakota#Sioux#Wounded Knee#AIM#seamstress#cook#star quilts#driver#community chairwoman#mother#grandmother#beloved aunt and sister#may she rest in peace#<3

90 notes

·

View notes

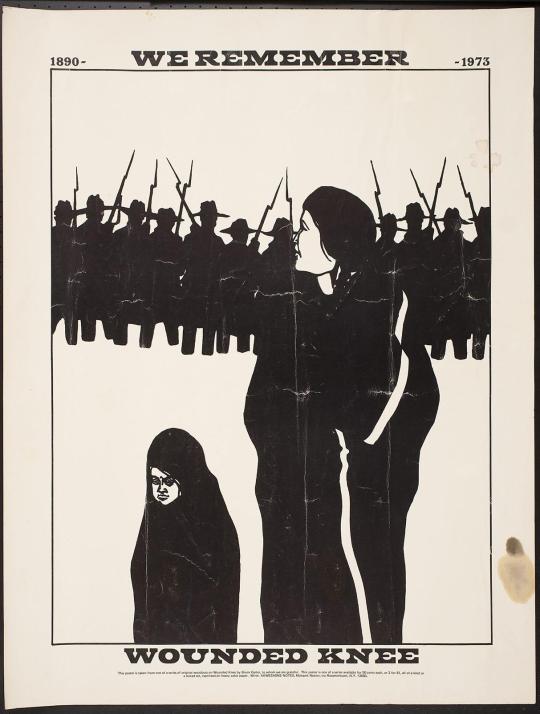

Text

Bruce Carter : We Remember Wounded Knee : 1890-1973 (1974)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today was the anniversary of this shameful moment. I didn’t realize that the author of The Wizard of Oz was so instrumental in drumming up anti-Indigenous hatred during this same period. Braum’s family has since apologized. Unfortunately, we can’t undo the damage he caused. We should learn from it, though.

#indigenous history#colonization#wounded knee#it wasn’t a battle it was a mass murder#wizard of oz#pop culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people's dream died there. It was a beautiful dream. And I, to whom so great a vision was given in my youth, — you see me now a pitiful old man who has done nothing, for the nation's hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead."

-Black Elk (Heȟáka Sápa) on the Wounded Knee Massacre.

#indigenous rights#native americans#lakota#black elk#indiginous#native american rights#wounded knee#wounded knee massacre#lakota sioux#sioux#sioux nation#american imperialism#imperialism#atrocities#human rights violations#human rights abuses#indigenous peoples#first nations#anti imperialism#racial and ethnic discrimination#racism in america#racial justice

4 notes

·

View notes