#which is a stokely carmichael speech

Text

youtube

Not enough people know that Agua, from Bomb Rush Cyberfunk, is a remix of a track from the most recent Spongebob Movie.

#bomb rush cyberfunk#BRC#spongebob#Like#it slaps regardless#it's a good song either way#but its like how da people uses the same samples that concept of love does#which is a stokely carmichael speech#free huey!#good stuff honestly#Youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speech excerpt by Stokely Carmichael, Free Huey Rally, February 17th 1968

It is a question of how we regain our humanity and begin to live as a people. And we do not do that because of the effects of racism in this country. We must, therefore, consciously stride for an ideology which deals with racism first. And if we do that, we recognize the necessity of hooking up with the 900 million black people in the world today.

That’s what we recognize.

And if we recognize that, then it means that our political situation MUST BECOME INTERNATIONAL; it cannot be national. It cannot be national.

It MUST be international! MUST be international!

It must be international because if we knew anything we would recognize that the honkies just don’t exploit us, they exploit the whole Third World: Asia, Africa, Latin America. They take advantage of Europe, but they don’t colonize Europe, they colonize Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Understand THAT!

If we begin to understand that, then the problems that America’s heading for becomes uppermost in our mind. The first one that they’re heading for is the conflict in the Middle East. WE MUST DECLARE ON WHOSE SIDE WE STAND! We can be for no one but the Arabs. There can be no doubt in our mind!

No doubt in our mind! No doubt in our mind!

We can be for no one but the Arabs because Israel belonged to the Arabs in 1917. The British gave it to a group of Zionists who went to Israel, ran the Palestine… the Palestinian Arabs out with terrorist groups, and organized the State, and did not get anywhere until Hitler came along and they swelled the State in 1948. That country belongs to the Palestinians. Not only that: they’re moving to take over Egypt. Egypt is our Motherland--it’s in Africa!

Africa!

We do not understand the concept of love. Here are a group of Zionists who come anywhere they want to and organize love and feeling for a place called Israel, which was created in 1948, where their youth are willing to go and fight for Israel. Egypt belongs to us. Four thousand years ago, and we sit here supporting the Zionists. We got to be for the Arabs. Period! Period!

#palestine#free gaza#current events#free palestine#gaza#gaza genocide#gaza strip#gazaunderattack#genocide#fuck israel#all eyes on rafah#rafah#save rafah#free rafah#rafah under attack#rafah crossing#west bank#israeli occupation#free west bank#iof terrorism#israeli apartheid#black panther party#stokely carmichael#huey p newton

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was reading thru the stokely Carmichael/kwame ture speech from 1968 from which the “understand the concept of love” sample comes, after I saw some ppl reblogging about it, and there are some very remarkable passages. A large portion of the speech is dedicated to a denunciation of “the programs that they [white america] run through our [black americas] throats,” these being in main

the franchise (“The vote in this country is, has been and always will be irrelevant to the lives of black people”)

The welfare state and the war on poverty (“It is designed to, number one, split the black community, and, number two, split the black family.”) and

state education (“unless WE control the education system, […] no need to send anybody to school--that’s just a natural fact.”)

From our vantage half a century later It’d be hard to think of a better example of three wishes duly granted by a maliciously faithful genie

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHRONOLOGY OF AMERICAN RACE RIOTS AND RACIAL VIOLENCE p-5

1961

May First Freedom Ride.

1962

Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU) is founded.

Robert F. Williams publishes Negroes with Guns, exploring Williams’ philosophy of black self-defense.

October Two die in riots when President John F. Kennedy sends troops to Oxford,Mississippi, to allow James Meredith to become the first African American student to register for classes at the University of Mississippi.

1963

Publication of The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin.

Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) is founded.

April Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., writes his ‘‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’’

June Civil rights leader Medgar Evers is assassinated in Mississippi.

August March on Washington; Rev. King delivers his ‘‘I Have a Dream’’ speech before the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

September Four African American girls—Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Addie Mae Collins—are killed when a bomb explodes at theSixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

1964

June–August Three Freedom Summer activists—James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—are arrested in Philadelphia, Mississippi; their bodies are discovered six weeks later; white resistance to Freedom Summer activities leads

to six deaths, numerous injuries and arrests, and property damage acrossMississippi.

July President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act.

New York City (Harlem) riot.

Rochester, New York, riot.

Brooklyn, New York, riot.

August Riots in Jersey City, Paterson, and Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Chicago, Illinois, riot.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, riot.

1965

February While participating in a civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama,

Jimmie Lee Jackson is shot by an Alabama state trooper.

Malcolm X is assassinated while speaking in New York City.

March Bloody Sunday march ends with civil rights marchers attacked and beaten by local lawmen at the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma, Alabama.

Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) is formed in Lowndes County,Alabama.

First distribution of The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, better known as The Moynihan Report, which was written by Undersecretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Nathan Glazer.

July Springfield, Massachusetts, riot.

August Los Angeles (Watts), California, riot.

1965–1967

A series of northern urban riots occurring during these years, including disorders in the Watts section of Los Angeles, California (1965), Newark, New Jersey (1967), and

Detroit, Michigan (1967), becomes known as the Long Hot Summer Riots.

1966

May Stokely Carmichael elected national director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

June James Meredith is wounded by a sniper while walking from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi; Meredith’s March Against Fear is taken up by Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, and others.

July Cleveland, Ohio, riot.

Murder of civil rights demonstrator Clarence Triggs in Bogalusa, Louisiana.

September Dayton, Ohio, riot.

San Francisco (Hunters Point), California, riot.

October Black Panther Party (BPP) founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

1967

Publication of Black Power: The Politics of Liberation by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton.

May Civil rights worker Benjamin Brown is shot in the back during a student protest in Jackson, Mississippi.

H. Rap Brown succeeds Stokely Carmichael as national director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Texas Southern University riot (Houston, Texas).

June Atlanta, Georgia, riot.

Buffalo, New York, riot.

Cincinnati, Ohio, riot.

Boston, Massachusetts, riot.

July Detroit, Michigan, riot.

Newark, New Jersey, riot.

1968

Publication of Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver.

February During the so-called Orangeburg, South Carolina Massacre, three black college students are killed and twenty-seven others are injured in a confrontation with police on the adjoining campuses of South Carolina State College and Claflin College.

March Kerner Commission Report is published.

April Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., is assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Washington, D.C., riot.

Cincinnati, Ohio, riot.

August Antiwar protestors disrupt the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

1969

May James Forman of the SNCC reads his Black Manifesto, which calls for monetary reparations for the crime of slavery, to the congregation of Riverside Church in New York; many in the congregation walk out in protest.

July York, Pennsylvania, riot.

1970

May Two unarmed black students are shot and killed by police attempting to control civil

rights demonstrators at Jackson State University in Mississippi.

Augusta, Georgia, riot.

July New Bedford, Massachusetts, riot.

Asbury Park, New Jersey, riot.

1973

July So-called Dallas Disturbance results from community anger over the murder of a twelve-year-old Mexican-American boy by a Dallas police officer.

1975–1976

A series of antibusing riots rock Boston, Massachusetts, with the violence reaching a climax in April 1976.

1976

February Pensacola, Florida, riot.

1980

May Miami, Florida, riot.

1981

March Michael Donald, a black man, is beaten and murdered by Ku Klux Klan members in Mobile, Alabama.

1982

December Miami, Florida, riot.

1985

May Philadelphia police drop a bomb on MOVE headquarters, thereby starting a fire that consumed a city block.

1986

December Three black men are beaten and chased by a gang of white teenagers in Howard Beach, New York; one of the victims of the so-called Howard Beach Incident is killed while trying to flee from his attackers.

1987

February–April Tampa, Florida, riots.

1989

Release of Spike Lee’s film, Do the Right Thing.

Representative John Conyers introduces the first reparations bill into Congress—the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act; this and all subsequent reparations measures fail passage.

August Murder of Yusef Hawkins, an African American student killed by Italian-American youths in Bensonhurst, New York.

1991

March Shooting in Los Angeles of an African American girl, fifteen-year-old Latasha Harlins, by a Korean woman who accused the girl of stealing.

Los Angeles police officers are caught on videotape beating African American motorist Rodney King.

1992

April Los Angeles (Rodney King), California, riot.

1994

Survivors of the Rosewood, Florida, riot of 1923 receive reparations.

February Standing trial for a third time, Byron de la Beckwith is convicted of murdering civil rights worker Medgar Evers in June 1963.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nashville Race Riot occurred on April 8, 1967, when African American students from Fisk University and Tennessee A&I University proted along Jefferson Street leading to many injuries and arrests as well as extensive property damage. The Nashville Race Riot was one of the many race riots that occurred in US cities during the spring and summer of 1967.

Some authorities incorrectly blamed the violence on Stokely Carmichael who came to speak at Fisk University, Tennessee A&I University, and Vanderbilt University. Fisk University and Tennessee A&I University officials attempted to prohibit Carmichael from coming to their college campus to speak to the students. Fisk University student threatening to move the event to a nearby church. Tennessee A&I University students were planning to hold their rally for him to speak outside their college campus.

On April 6, 1967, Carmichael spoke at Fisk University urging them to become involved in the growing Black Power Movement. He spoke to the Tennessee A&I University students and encouraged the students there to organize and take economic control of the African American community which he claimed was one of the goals of the Black Power Movement.

On April 8, 1967, Carmichael gave a similar speech at Vanderbilt University. A riot erupted around North Nashville. The riot started when a Black manager of the University Inn, called the police to remove a drunken, disruptive solider from the establishment. Once the police arrived and removed the soldier, Fisk University and Tennessee A&I students started an impromptu picket line around the University Inn.

Fourteen people were injured. The riots continued the following day at Tennessee A&I University where Molotov cocktails were thrown through the windows of several businesses including a liquor store, a gas station, and a barbershop. At least a dozen people were injured. An estimated 40 people were arrested during the second day of the riot.

On April 10, 1967, Nashville Mayor Beverly Briley called for an end to the violence and increased the police presence in the area. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a battle for social justice that mostly occurred in the 1950s and 1960s in order for Black Americans to acquire equal legal rights in the United States. Although the Civil War legally ended slavery, it did not stop discrimination against Black people, who continued to suffer the terrible impacts of racism, particularly in the South. By the mid-twentieth century, Black Americans had had enough of bigotry and violence directed against them. They, together with many white Americans, organised and launched a historic two-decade campaign for equality. On February 1, 1960, four college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, took a stance against segregation by refusing to leave a Woolworth's lunch counter without being served. Hundreds of people joined their cause in what became known as the Greensboro sit-ins over the next few days. After some students were detained and charged with trespassing, demonstrators called for a boycott of all segregated lunch counters until the proprietors relented and the initial four students were ultimately served at the Woolworth's lunch counter where they'd first stood their ground. Their activities helped form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which encouraged other students to get part in the civil rights struggle through nonviolent sit-ins and protests in dozens of cities. It also piqued the interest of Stokely Carmichael, a young college graduate who joined the SNCC during the Freedom Summer of 1964 to register Black voters in Mississippi. In 1966, Carmichael was elected chair of the SNCC and delivered his famous speech in which he coined the phrase "Black power."

youtube

On May 4, 1961, 13 "Freedom Riders"—seven Black and six white activists—boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington, D.C., for a bus tour through the American south to protest segregated bus terminals. They were putting to the test the 1960 Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia, which deemed interstate transportation facility segregation illegal. The Freedom Rides garnered international attention as they faced violence from both police officers and white protestors. On Mother's Day 1961, the bus arrived in Anniston, Alabama, where a mob boarded it and detonated a bomb. The Freedom Riders were savagely assaulted after escaping the burning bus. Photos of the bus engulfed in flames went viral, and the gang was unable to locate a bus driver to carry them any farther. The Freedom Riders continued their journey under police protection on May 20 after US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy (brother to President John F. Kennedy) worked with Alabama Governor John Patterson to secure a suitable driver. However, the cops abandoned the passengers until they arrived in Montgomery, where a white mob viciously assaulted the bus. Attorney General John F. Kennedy sent federal marshals to Montgomery in response to the riders and a summons from Martin Luther King Jr. A group of Freedom Riders arrived in Jackson, Mississippi on May 24, 1961. Despite the backing of hundreds of people, the group was arrested for trespassing in a "whites-only" institution and sentenced to 30 days in jail. Attorneys for the NAACP took the case to the United States Supreme Court, which overturned the convictions. Hundreds of new Freedom Riders were drawn to the cause, and the rides continued. In the fall of 1961, under pressure from the Kennedy administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals.

youtube

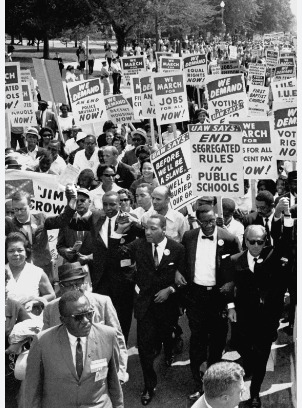

On August 28, 1963, one of the most renowned events of the civil rights movement occurred: the March on Washington. Civil rights activists such as A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King Jr. planned and attended. More than 200,000 people of all colours gathered in Washington, D.C. for a peaceful march aimed at imposing civil rights legislation and creating workplace equality for everyone. The march's high point was King's address, in which he repeatedly proclaimed, "I have a dream…" The speech "I Have a Dream" by Martin Luther King Jr. energised the national civil rights movement and became a rallying cry for equality and freedom.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Civil rights

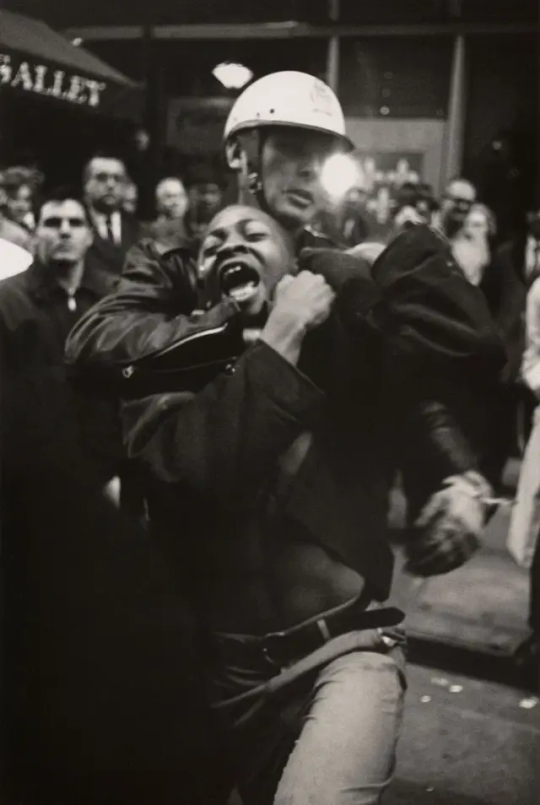

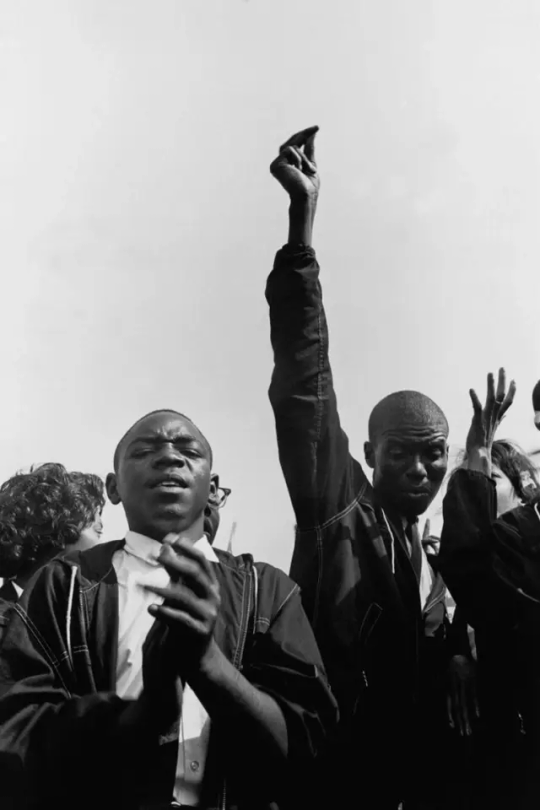

In the summer of 1962, Lyon hitchhiked to Cairo, Illinois, to witness demonstrations and a speech by John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the most important organisations driving the civil rights movement of the early 1960s. Inspired to see the making of history firsthand, Lyon then headed to the South to participate in and photograph the civil rights movement. There, SNCC executive director James Forman recruited Lyon to be the organisation’s first official photographer, based out of its Atlanta headquarters. Traveling throughout the South with SNCC, Lyon documented sit-ins, marches, funerals, and violent clashes with the police, often developing his negatives quickly in makeshift darkrooms.

Lyon’s photographs were used in political posters, brochures, and leaflets produced by SNCC to raise money and recruit workers to the movement. Julian Bond, the communications director of SNCC, wrote of Lyon’s pictures, “They put faces on the movement, put courage in the fearful, shone light on darkness, and helped make the movement move.”

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Sit-In, Atlanta

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.1 x 24cm (6 3/8 x 9 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)The Leesburg Stockade, Leesburg, Georgia

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17.5 x 26cm (6 7/8 x 10 3/16 in.)

Sheet: 27.9 x 35.6cm (11 x 14 in.)

Collection of the artist

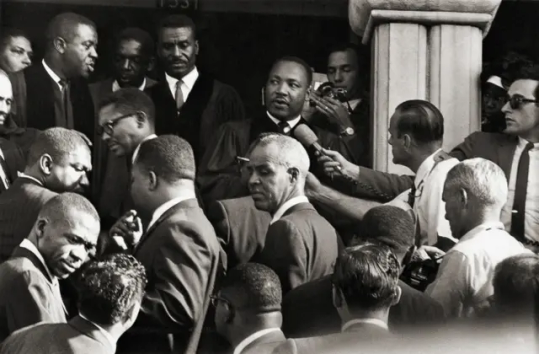

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)

Abernathy, Shuttlesworth (SCLC), King and Wilkinson (NAACP)

1963

Gelatin silver print

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Voting Rights Demonstration, Organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Selma, Alabama

October 7, 1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.3 x 26.8cm (7 3/16 x 10 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 27.8 x 35.4cm (10 15/16 x 13 15/16 in.)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Sheriff Jim Clark Arresting Demonstrators, Selma, Alabama

October 7, 1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 18.4 x 27cm (7 1/4 x 10 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 27.8 x 35.4cm (10 15/16 x 13 15/16 in.)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchased with funds from the Photography Committee

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Stokely Carmichael, Confrontation with National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland

1964

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.5 x 22.2cm (6 1/2 x 8 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Collection of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta; purchase with funds from Joan N. Whitcomb

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)

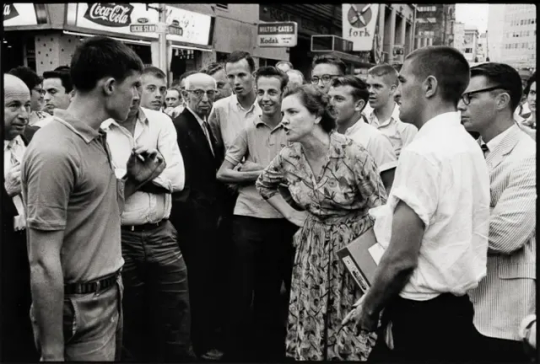

Woman Holds Off a Mob, Atlanta

1963

Gelatin silver print

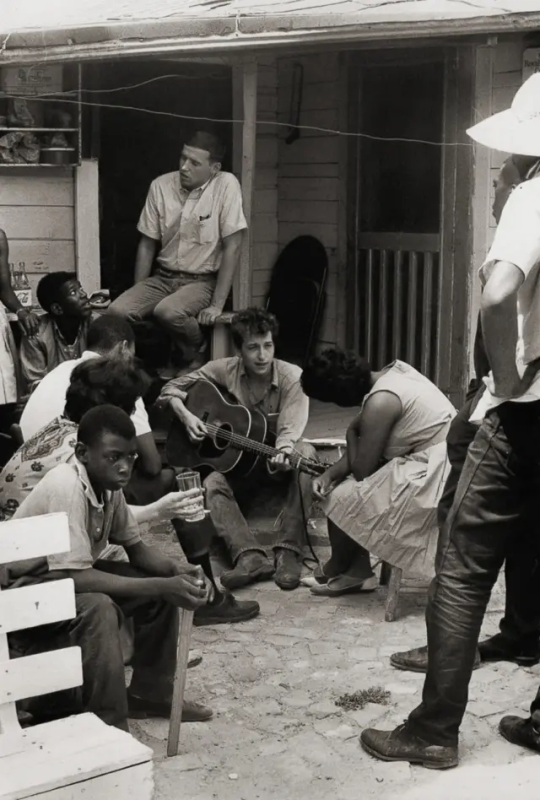

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)

Bob Dylan behind the SNCC office, Greenwood, Mississippi

1963

Gelatin silver print

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Arrest of Taylor Washington, Atlanta

1963

Gelatin silver print

24 x 16cm (9 7/16 x 6 1/4 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)The March on Washington

August 28, 1963

Gelatin silver print

29.8 x 20.8cm (11 3/4 x 8 3/16 in.)

Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of Anne Ehrenkranz

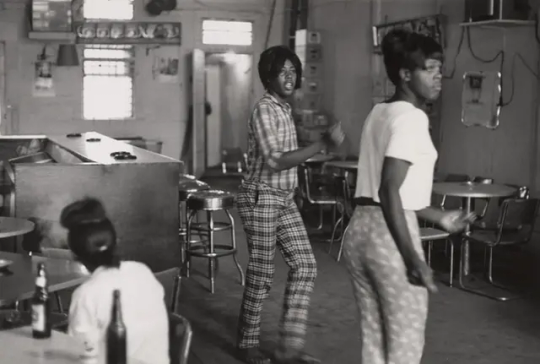

Galveston

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Pumpkin and Roberta, Galveston, Texas

1967

Gelatin silver print

Image: 23.8 x 16.1cm (6 3/8 x 9 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Collection of the artist

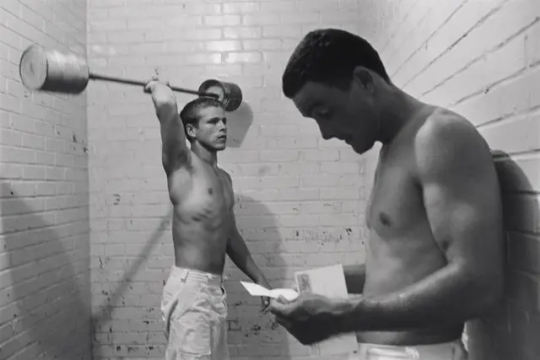

Prisons

In 1967, Lyon applied to the Texas Department of Corrections for access to the state prisons. Dr. George Beto, then director of the prisons, granted Lyon the right to move freely among the various prison units, which he photographed and filmed extensively over a fourteen-month period. The result is a searing record of the Texas penal system and, symbolically, of incarceration everywhere.

Lyon’s aim was to “make a picture of imprisonment as distressing as I knew it to be in reality.” This meant riding out to the fields to follow prisoners toiling in the sun, as well as visiting the Wynne Treatment Centre, which housed primarily convicts with mental disabilities. He befriended many of the prisoners, listening to their stories and finding the humanity in their experiences, and still maintains contact with some of them.

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Weight Lifters, Ramsey Unit, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image: 22.4 x 33.2cm (8 7/8 x 13 1/16 in.)

Sheet: 27.7 x 35.6cm (11 x 14 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)New Arrivals from Corpus Christi, The Walls, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image: 21.4 x 32cm (8 7/16 x 12 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 27.9 x 35.6cm (11 x 14 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Contents of Arriving Prisoner’s Wallet, Diagnostic Unit, The Walls, Huntsville, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.3 x 17.5cm (9 9/16 x 6 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 25.4 x 20.3cm (10 x 8 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Shakedown, Ramsey Unit, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17 x 24.2cm (6 5/8 x 9 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Collection of the artist

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Convict With a Bag of Cotton, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)Two Inmates, Goree Unit, Texas

1968

Gelatin silver print

Image: 16.8 x 24cm (6 5/8 x 9 91/6 in.)

Sheet: 20.3 x 25.4cm (8 x 10 in.)

Collection of the artist

#Danny Lyon#Leesburg Stockade#Civil Rights Movement#Voting Rights#Texas#Mississippi#Georgia#Alabama#prison#March on Washington#martin luther king jr#black lives matter#atlanta#maryland#sncc

1 note

·

View note

Text

Graphic match - Pg 220

A graphic match (as opposed to a graphic contrast or collision) occurs when the shapes, colors and/or overall movement of two shots match in composition, either within a scene or, especially, across a transition between two scenes.

In the ongoing fight for equality scene at the end of the film

after the double dolly shot there is a cross burning shot in a field which cuts to flaming torches with people holding them, rioting and shouting 'white lives matter'

Rhythmic match-Pg 224

RHYTHM editing describes an assembling of shots and/or sequences according to a rhythmic pattern of some kind, usually dictated by music.

Every shot is of a certain length, with its series of frames consuming a certain amount of time onscreen.

In "Too late to turn back now scene" when Ron Stallworth and Patrice are dancing to " I believe , i believe I'm falling in love" , it is cut Rhythmically.

Spatial match pg 225

Spatial editing is when the relations between shots function to construct film space.

Characteristics:

establishes a whole and separates it into parts OR

establishes parts to create a whole.

Example: In the beginning scenes of the film, Ron stallworth enters into the frame, next shot is we see 'Join the Colorado springs police force' banner and next we see a shot of the sign 'board of Colorado springs police department' which cuts to two police officers sitting (Chief Bridges ) inside a police building ..

This allows the film to relate any two points in space through similarity, difference, or development.

Eyeline match Pg 234

A cut that follows a shot of a character looking offscreen with a shot of a subject whose screen position matches the gaze of the character in the first shot.

In an eye-line match, a shot of a character looking at something cuts to another shot showing exactly what the character sees. Essentially, the camera temporarily becomes the character’s eyes with this editing technique.

Klan vs Ron vs Police Scene towards the end of the film.

Ron Stallworth runs to stop Connie from bombing Patrice home. Ron gets stopped by the police for catching Connie and unknowingly, Felix kills himself, Ivanhoe, and Walker by pressing the button to the bomb while parked right next to the car. In this scene we see eye line match editing with the Car burning from bomb blast ,Ron lying on floor etc .

Parallel editing or crosscutting Pg 244

An editing technique is the process of alternating between two or more scenes that happen simultaneously in different locations within the world of the film

The scene featuring undercover cop Flip Zimmerman’s (Adam Driver) KKK initiation ceremony, which is cross-cut with civil rights icon Harry Belafonte, as Jerome Turner, talking with student activists. Turner describes the horrific true story of witnessing the lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, in 1916. Brown then addresses the impact of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 Birth of a Nation, cutting back and forth to the KKK initiation, where the participants are now watching Birth of a Nation and cheering.

Also , One can notice cross cutting in Ron’s first undercover assignment was monitoring a speech by Black Panther Stokely Carmichael and cops waiting outside.

Another scene is Charlottesville Riot Footage cross cut with trump's speech.

0 notes

Photo

That all this time later we are still learning new information about Hampton’s killing is testament to the sheer volume of the effort aimed at this young revolutionary.

“This was a masterplan for destroying radical black nationalist groups.”

The horrifying story of the 1969 police murder of Fred Hampton is now well known. But there’s still much to be revealed about the case — like the information in bureau files newly obtained by Jacobin showing the FBI awarded Special Agent Roy Martin Mitchell, the handler of informant William O’Neal who was key to the raid that killed Hampton, a $200 bonus for work well done.

In the predawn hours of December 4, 1969, fourteen Chicago Police officers, claiming they were searching for illegal weapons, crashed into a first floor apartment on Chicago’s Monroe Street and opened fire. Inside were nine members of the Illinois Black Panther Party, including the rising star of the chapter, Fred Hampton.

The police claimed the apartment’s occupants fired on them, but after a fusillade of more than ninety bullets, the only people shot were Panthers, including Mark Clark and Hampton, who were dead. The picture of grinning cops carrying Hampton’s body out of the apartment that circulated in the wake of the killing said it all: the Chicago Police Department (CPD) had wanted Hampton dead. Their mission was accomplished.

The Chicago police, however, were not the only ones celebrating. We now know that within days of the murderous operation, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) awarded their Special Agent Roy Martin Mitchell, the handler of the informant who was key to the raid, a $200 bonus for work well done. This, and other information is contained in documents obtained by Aaron Leonard — posted here for the first time — via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

The murder of Fred Hampton remains a point of tremendous outrage and debate decades after the fact — most recently thrust into the spotlight with the release of the film Judas and the Black Messiah . Too often there is an assumption that all facts are known. But with these new documents and others released in the past few years, it is clear there is more to uncover — not only for the sake of historical accuracy, but to understand how the bureau targeted those who were deemed threats to the status quo, so we can try to ensure such voices will not be silenced in the future.

COINTELPRO: “Black Nationalist Hate Groups”

When speaking of Fred Hampton the term COINTELPRO, the syllabic abbreviation for counterintelligence program, has become near-synonymous with his killing. So it is worth looking at what the COINTELPRO aimed at the Black Panther Party (BPP) actually was.

The United States at the end of the 1960s was in tumult. The antiwar movement was radicalizing, Catholic pacifists were destroying draft records, and the black freedom movement was giving way to Black Power and armed self-defense. Against this backdrop, in August 1967 the FBI launched a program called “COINTELPRO, Black Nationalist Hate Groups,” expanding on an effort begun in the mid 1950s directed at the Communist Party. The Bureau soon expanded the program. In a memo issued on March 4, 1968 , they elaborated on its objectives:

1) Prevent the coalition of black nationalist groups

2) Prevent the rise of a “messiah” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement [here citing Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, Elijah Muhammad, and Stokely Carmichael as examples]

3) Prevent violence on the part of black nationalist groups

4) Prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining respectability

5) Prevent the long-range growth of militant black nationalist organizations, especially among youth

Taken as a whole, this was a masterplan for destroying radical black nationalist groups. As 1968 gave way to 1969, the Bureau was particularly fixated on the Black Panther Party.

The Black Nationalist Hate Groups COINTELPRO was a major undertaking, and its exposure played a large role in forcing the Bureau to curtail domestic security operations in the mid-1970s. But COINTELPRO was just one piece of the Bureau’s larger toolkit against radicals, one that included surveillance, informant infiltration, intelligence gathering, and compiling lists for possible detention, and working with local police and their red squads to achieve these goals. Understanding this gives a much clearer picture of what Hampton and the Chicago BPP were up against.

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, which started in Oakland in 1966, did not get its start in Chicago until the end of 1968. Around this time, elements of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), including leaders Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), James Forman , and H. Rap Brown, briefly joined the BPP. In Chicago, this included SNCC member Bob Brown, who would become one of the chapter’s original members, along with Bobby Rush, and twenty-one-years-old NAACP Youth Chapter leader Fred Hampton. While the Panther-SNCC merger ultimately fell apart, the Chicago BPP did not.

From the start, the FBI was all over the Chicago chapter, having the advantage of an informant who joined the group as it was forming. William O’Neal had been recruited by FBI Special Agent Roy Martin Mitchell. Mitchell, who had learned that O’Neal had stolen a car and crossed state lines — making his case a federal one — used that as leverage to turn him into a snitch. According to O’Neal, Mitchell told him:

“I know you did it, but it’s no big thing.” He said, “I’m sure we can work it out.” And, um, I think a few, few months passed before I heard from him again, and one day I got a call and he told me that it was payback time. He said that “I want you to go and see if you can join the Black Panther Party, and if you can, give me a call.”

O’Neal’s joining the Chicago chapter at its inception is consistent with a practice the Bureau had developed: aiming to embed informants into radical groups at their formation, where they could more easily assimilate and potentially rise in the ranks. This held true for O’Neal: who quickly became a security captain for the chapter. It also helps explain how the FBI was able to develop insightful, if not always successful, COINTELPRO efforts against the chapter.

“The Bureau aimed to embed informants into radical groups at their formation, where they could more easily assimilate and potentially rise in the ranks.”

One of the first measures they implemented was a “poison pen” letter sent to the Chicago Mau Mau street gang in December 1968. The letter purportedly from “a disgusted Black Panther,” slandered Bob Brown and Bobby Rush “as opportunists and hustlers out for their own personal gain.”

A month later they again tried to foment divisions, this by sending an incendiary letter to the Black P. Stone Nation , a formidable street gang, which was already in conflict with the Panthers over recruitment. The letter from “A Black brother you don’t know,” claimed “the Panthers blame you for blocking their thing and there’s supposed to be a hit out on you. […] I know what I’d do if I was you.” Fortunately cooler heads prevailed, though such was not the intent of the letter.

These were official COINTELPRO operations, meaning they had to be proposed and approved within the FBI hierarchy. Notably, they were not singularly targeted at Fred Hampton. Our research has only been able to find one example where Hampton is the explicit target.

That plan, outlined, in a November 25, 1969 memo , proposed sending a letter from “a disgruntled Panther” to the national office that would state:

“Myself and other brothers are getting tired of the screwing Hampton [Name REDACTED] are giving the brothers and sisters here in Chicago and the brothers in Berkeley. Last week [REDACTED] and Hampton called us all in for a meeting and the M….F……told us we are purged from the Party. All the time they are bitching about you no good nigger. [sic] They say you only think of Chicago when you need bread. You don’t give a damn about all our brothers in jail….”

The fodder for the letter was an incident in which Hampton had suspended a group of Chicago Panthers (the memo says “purged” until they “‘earned’ the right to be called a Panther”) for being late to a meeting. The letter’s aim was to sabotage plans for Hampton to move up the Panther hierarchy by joining the national office.

Notably, that same proposal shows up in a memo dated December 3, 1969 , which also references “a positive course of action” the Chicago Police Department were about to carry out (i.e., the raid, using intelligence the FBI had passed on to them from their informant William O’Neal).

“The letter’s aim was to sabotage plans for Hampton to move up the Panther hierarchy.”

It is confusing that both the raid and the proposed COINTELPRO against Hampton are mentioned in the same memo, suggesting the FBI’s effort against Hampton were more ongoing and they did not anticipate he would be killed the following day. At minimum, more information is needed to understand what the FBI was aware of about the imminent CPD raid.

The Chicago BPP in 1969 was in the middle of a tempest. On the one hand, the chapter was in the midst of an influx of new members, and the party was seen by many black youth as an electrifying force. Hampton himself was in high demand for giving speeches to organizations and on college campuses. Meanwhile police were routinely raiding BPP headquarters, the media was vilifying them, members were being arrested with minor charges transforming into major ones, and various secret police were working in the background to sabotage their efforts to work with and unite with other forces.

The CPD & the Red Squad

The murder of Fred Hampton unfolded against a pitched dynamic of raids and armed self-defense. In 1969, the Panther headquarters in Chicago was raided three times, first by the FBI and twice by the CPD. Such an extraordinary situation helps explain the Panthers’ emphasis on security and self-defense.

Meanwhile, there were forces in operation in the background beyond the FBI. While the Panthers repeatedly ran up against Chicago street cops, the CPD also had a sizable intelligence component, operating under different names over the years but generally referred to as “the red squad.”

For a single city, the operation was huge. In his 1990 book Protectors of the Privilege, which documented the activity of big-city red squads, late ACLU director Frank Donner, called Chicago the “National Capital of Police Repression.” He reported that in 1970, 382 people were assigned to the unit, with forty-nine specifically targeting “subversives.” Not surprisingly, the Panthers were a target. According to former Panther Billy “Che” Brooks , the Chicago chapter was under the constant eye of the Chicago Red Squad and Gang Intelligence Unit.

“ACLU director Frank Donner called Chicago the ‘National Capital of Police Repression.’”

It was against that backdrop that the CPD’s targeting of the BPP reached a crescendo. On November 13, Panthers Lance Bell and Spurgeon “Jake” Winters were in the abandoned Washington Park Hotel when police were called out to them. Bell fled the scene, but Winters engaged cops in a running shootout, killing one and wounding nine officers. After an extensive chase, he shot one of the two officers on his trail, knocking him down. According to the account in Black Against Empire : The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr, as the other officers rushed forward, “Winters walked to the fallen officer, purposely raised his gun, and shot the officer in the face.” Winter was in turn killed by approaching police.

According to informant William O’Neal, this was the incident that set the CPD on a course of murderous revenge that would result in the killing of Fred Hampton.

The Rising Informant

It was against this backdrop that positions in the Chicago BPP chapter were constantly shifting. In the case of FBI informant William O’Neal, he appeared to be on the rise. This comes through in a 1,636-page document released by the FBI in 2017 (under the JFK Assassination Records Collection Act), which includes numerous reports from SA Mitchell and an informant — most likely O’Neal.

Specifically, one document has SA Mitchell reporting , “HAMPTON is allegedly considering approaching O’NEAL to see if he will take over as acting Minister of Defense if RUSH goes to jail.” At the time, Bobby Rush was facing jail for possession of an unregistered weapon, stemming from a police arrest after a Panther speaking event in Urbana, Illinois.

While O’Neal was rumored for promotion, Hampton himself was confronting prison for an incident in which an ice cream truck was looted of $71 worth of merchandise and distributed to neighborhood youth. Hampton would be convicted at trial and later released on bail, but lost his appeal on November 26 and was facing a return to jail to serve an excessive two- to five-year sentence.

The CPD were apparently in no mood to await Hampton’s imprisonment. Here, the FBI’s informant William O’Neal played a key role. It was O’Neal’s floor plan, a rough diagram , later refined by Mitchell of the apartment where Hampton and other Panthers were staying, which was given to the CPD raiding party — a document that lawyers Jeff Haas and Flint Taylor were able to pry loose in a later civil trial. While this is hard evidence of O’Neal’s role, many accounts of the murder also claimed that O’Neal drugged Hampton the night before the killing. That evidence, however, is still in dispute .

O’Neal’s role in supplying the floor plan, and the fact that he was given a $300 bonus a week after Hampton’s murder, has been known for some time. What had not been known previously, and which we learned with the release of 491 pages in SA Mitchell’s personal file, is the degree to which the Bureau was following, encouraging, and rewarding O’Neal and Mitchell throughout 1969 — culminating in a personal commendation by J. Edgar Hoover himself for Mitchell, days after Hampton’s murder:

“Through your aggressiveness and skill in handling a valuable source, he is able to furnish information of great importance to the Bureau in this vital area of our operations. I want you to know of my appreciation for your exemplary efforts.”

“It was O’Neal’s floor plan which was given to the CPD raiding party.”

In the memo, Hoover is careful not to spell out what the “vital area of our operations” is. But a notation on the letter reads, “Re: Black Panther Party,” making clear it was his work against the BPP. Further diminishing the commendation’s vagueness, another note references a “Moore-Sullivan” writing on December 2, 1969 that recommends the award for Mitchell’s “development of a highly productive informant in the Black Panther Party” — almost certainly William O’Neal.

Notably, the same day Hoover congratulated Mitchell, the FBI issued a COINTELPRO memo following up on the proposed poison pen letter aimed at Hampton. In it, they noted, “In view of the fact that Hampton was recently shot and killed by Chicago police, no further action is being taken in regard to your proposal.”

It remains unclear all the details the FBI knew about the CPD raid at the moment Hoover wrote to SA Mitchell. But it is clear that they knew their informant, carefully cultivated over months, had played an integral role in the “success” of an undertaking where the only people shot were Black Panthers awoken from their sleep, two of whom were shot dead. That in that moment, the Bureau chose to reward their agent’s work further closes a loop of culpability: it was blood money for a bloody deed.

Still More to Uncover

The Fred Hampton story has been told and retold such that it is frozen in amber, as if all the facts are known. Yet our obtaining of previously secret documents shows there is still more to be learned — not only from the corpus of files held by the FBI, but from the files of Chicago’s SAC Marlin Johnson, the informant William O’Neal’s file, any liaison notes between the CPD and the FBI that may exist, to say nothing of information that may lie in the records, not destroyed , of the Chicago Police and their red squad. (The CPD admitted in 1974 that it destroyed 105,000 files on individuals and 1,300 on organizations .) That all this time later we are still learning new information about Hampton’s killing is testament to the sheer volume of the effort aimed at this young revolutionary — and hopefully a spur to finally get all the secrets out.

This article previously appeared in Jacobin and Reader Supported News .

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Study the path of others to make your way easier and more abundant. Lean toward the whispers of your own heart, discover the universal truth, and follow its dictates... Release the need to hate, to harbor division, and the enticement of revenge. Release all bitterness. Hold only love, only peace in your heart, knowing that the battle of good to overcome evil is already won. Choose confrontation wisely, but when it is your time don't be afraid to stand up, speak up, and speak out against injustice. And if you follow your truth down the road to peace and the affirmation of love, if you shine like a beacon for all to see, then the poetry of all the great dreamers and philosophers is yours to manifest in a nation, a world community, and a beloved community that is finally at peace with itself.

- John Lewis, civil rights campaigner and US congressman (1940-2020)

John Lewis, who went from being the youngest leader of the 1963 March on Washington to a long-serving congressman from Georgia and icon of the civil rights movement, died at the grand old age of 80 years old on 17 July 2020.

Born to sharecroppers in Troy, Alabama, in February 1940, Lewis became a prominent leader of the civil rights movement in the 1960s. He joined the Freedom Rides that began in 1961, traveling to the south by bus to fight segregation on interstate buses.

A founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he became its chair in 1963 and helped organise the March on Washington, when Martin Luther King Jr delivered his “I have a dream” speech.

In Selma, Alabama, in 1965, as activists tried to cross the Edmund Pettus bridge, Lewis was walking at the head of the march with his hands tucked in the pockets of his overcoat when he was knocked to the ground and beaten by police. His skull was fractured. Nationally televised images of the brutality forced attention on racial oppression in the south. That incident, along with other beatings during peaceful protests, left Lewis with scars for the rest of his life.

Within days, King led more marches in Alabama. President Lyndon B Johnson soon was pressing Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which became law later that year.

After Selma and with each passing month, SNCC became more militant. The organization grew to reflect the disappointment of those who saw progress as coming too slow. “Something was born in Selma, but something died there, too,” Lewis wrote in ���Walking With the Wind.” “The road of nonviolence had essentially run out.” (King’s assassination in 1968 was another devastating blow against those advocating nonviolence.)

In 1966, Lewis lost the chairmanship to Stokely Carmichael, champion of the slogan “Black Power.” “My life, my identity, most of my very existence, was tied to SNCC,” Lewis recalled in “Walking With the Wind.” “Now, so suddenly, I felt put out to pasture.”

In 1968, he worked on the presidential campaign of Robert F. Kennedy. On the night of the California primary, he was with the campaign at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles when Kennedy was shot and killed by Sirhan Sirhan.

He eventually got himself elected to the House of Representatives from Georgia and in time became its ‘conscience’ for members on both sides of the political aisle. As time passed, he came to be seen as the living embodiment of the civil rights movement.

Many awards came his way: a Lincoln Medal from Ford’s Theatre, a Preservation Hero award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the NAACP Spingarn Medal, the Liberty Medal from the National Constitution Center, a Dole Leadership Prize named for Bob Dole, and a John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for lifetime achievement, among others. Stephan James portrayed him in the 2014 movie “Selma.” Universities showered him with honorary degrees. In 2016, the U.S. Navy announced that it was naming a ship, a replenishment oiler, after him.

Out of all the stories I’ve read about John Lewis one story in particular stood out for me and captures something of what is missing in our current turbulent times.

In 2009, Lewis met with a white man named Elwin Wilson, who was among those who assaulted Lewis and other Freedom Riders in 1961. Following Obama’s election in 2008, Wilson said he had an epiphany and traveled to Washington to apologise for his violent acts and seek Lewis’ forgiveness. Lewis gave it freely.

“It’s in keeping with the philosophy of nonviolence,” Lewis later told the New York Times. “That’s what the movement was always about, to have the capacity to forgive and move toward reconciliation.”

If only today’s well intenioned but woefully intellectually muddled social justice warriors, both in the USA and increasingly here in the UK, could follow Lewis’ words and deeds.

46 notes

·

View notes

Audio

On Shop Windows and Being

“I include the personal here to connect the social forces on a specific, particular family’s being in the wake to those of all Black people in the wake; to mourn and to illustrate the ways our individual lives are always swept up in the wake produced and determined, though not absolutely, by the afterlives of slavery.” (Sharpe 2016, 5)

----

In one of my classes, my peer, Joi, shared her experience as a black ballerina. Their practice space was in a closed-down shoe store. The floors were replaced. Big mirrors and balance bars were installed against the walls, and across from the door lined tall shop windows. On the first day of class, at ten years old, Joi and the rest of the dancers sat cross-legged as their instructor introduced themselves. After sharing their names, their instructor told them, "Now as black girls - as black ballerinas, there aren't too many of us. Remember, they can see you." Joi explained to us the importance and the pain of this message. In her practice space, in her learning space, she did not feel free to make a single mistake. Because if she did, she'd not only be disappointment to her own reflection in the practice mirror, but reflect failure to those behind the glass.

What does it mean to be black, to be girl and constantly balancing, expanding, stretching, and splitting yourself into perfection? What can that mean for this body? Claude M. Steele makes Brent Staples' experience whistling Vivaldi the title of his first book in his decades-long career. Steele's work is to examine stereotype and how it affects all of us in a way that prevents us from living without burden or stress. In understanding identity and stereotype's threat to identity formulation, Steele shares Staples' experience as an example of not only the cognition a person experiencing stereotype threat may have, but tactics to cope. For Staples, he deflects fear against him and within him by whistling classical music. In this way, Staples reads as safe to passersby on his walk. As Steele writes, "This caused him to be seen differently, as an educated, refined person, not as a violence-prone African American youth." (Steele 2010, 7) And as I read this in class, I immediately think of another boy marked by youth and dark skin. Emmett Till, 14 years old, was deemed unsafe - in fact, deemed lethal target - due to whistling.

And whether or not Till did whistle does not matter, for many reasons. What matters is that it was reason enough.

For Till, whistling was justification for torture. For Staples, whistling was the only safety net he could think of. It strikes me how truly precarious being black is. There is no singular trick that can be universalized to promise our survival. Be it whistling, walking home, driving with your kids, being President, being President's daughters. There is no safety in this black skin.

When I think back to what my past career plans were and how they and my current experiences have shaped my future goals, I think it was always rooted in attempted escape. For the ability to slip into an imaginary that hugged me, a world that embraced me. For a long time, I coveted for a reality that loved me. I decided to use this space to explore each previous career plan that I translated to an iteration of Me. Be it writer, President or policymaker- I chose these titles because I could feel it projecting a Me the world could love. I yearn(ed) so much for a world that would just love Me.

----

Vocabulary was never my strong suit. It still isn't. And, when we were made to take those spelling tests in elementary school, I drilled myself as much as possible. Before test day, I'd eat alphabet soup for good favor from the Letter Gods; Give me that S on my paper. Even then I knew after all the preparation, I was never going to find myself using the words. Humongous? Big would be fine enough. Be damned synonyms. Be damned precision. I knew enough words to say what was on my mind without needing to do all that studying. But, I wasn't gonna be caught slipping on something everyone else was excelling in.

In fact, that's how I knocked out my two front teeth. My siblings were losing their teeth left and right, purchasing freeze pops after the Toothfairy's fair bargain. So, I grabbed one of my wood blocks, and knocked any loose tooth I could find. Twisted them until my gums gave out and gave up. And now here I am, teeth at a slant and still craving those sweets.

This vocabulary test offered extra credit, something I knew someone in my state - bloody gums, sticky fingers, alphabet soup brain - would need. We were told to make a short story, 10 sentences max, using at least 5 of the vocabulary words. So I made Ten, a young girl aged 9 with too much time on her hands, trying to whack her teeth out. Only thing I remember is that she rode a humongous hot air balloon, tied a brick around her teeth and chucked it into the air. The tooth went with it. Poor Ten. She was a Junie B. Jones copy to be sure, but she got me my S. My teacher pulled me aside and told me I was a great writer. A writer. Suddenly, it felt fitting to call myself: Stephanie, the writer. The one day published author. I had a definition of Me that felt so much cooler, so suave compared to my peers. I was going to be a writer.

I wrote all through middle school. Finished the Saga of Ten, started writing collaboratively with my best friend through Google Docs. What a joy it was to share this fun with someone. We'd swap our names and faces with the leading starlight of our time (regretably and instructively for two girls of color, it was Bella of Twilight), switch the heartthrobs to our Middle School Day Dreams and giggle and shy away and praise and write and write. I really had so much fun then.

I was lonely for much of my time in High school. I knew no one. I knew nothing. It felt like everyone knew which clubs to join, which teachers to meet with, knew what it meant to have a counselor AND an adviser. One for high school troubles and the other for career services. I was 14. But, they were too. And yet, they knew.

I was still Stephanie, the writer though. I did well in my Presentation classes and got along really well with my 9th grade Lit Teacher. She was so sweet to me. I think she knew I was a fish out of water. To find someone who loved writing like I did, like my best friend who rushed along at a different high school that felt like it was in a different time zone, to find someone like that again was a joy. It seemed like no one else connected to All Quiet on the Western Front or the Edgar Allen Poe like we did. I was still cool, suave writer Stephanie in the face of the unknown.

Then, we read Huckleberry Finn. Then, everyone was attentive. Everyone wanted to read along.

Then I heard my classmates say Nigger more times than I could care to count. I remember shooting up. Looking and being reminded that this wasn't Middle School anymore. These faces didn't look like mine. Hair didn't look like mine. Speech wasn't like mine even if they tried to copy. I was black girl in a white room, admiring a white teacher who let these white kids say Nigger. I didn't finish reading Huckleberry Finn. I stopped writing.

I wanted to cry, but what will the people think watching me? What will I think of Me, crouching, hiding near squeaky-clean glass? How is it possible to be stare at and unseen? I think that's why I was so angry after reading Recitatif. I fell for it too. Just like they did. Saw something unseeable, assigned roles to hair smell, to motherhood, to two girls with lapsing memory. Had I really not learned from my own pain?

I think that Lit class was the first moment that I realized I was behind shop windows too. Before, I thought I was a fellow admirer, struck by the fabrics spinning amongst themselves, silks sliding down cheeks, cotton snuggling up to noses. I'm always watching in awe as a They walk freely, playing in such pretty dress-up. I wanted to be out there. I wanted to feel silk. I wanted cotton to be comfort, not a reminder.

In 11th grade, I enrolled in AP US History. I scored well enough on Social Studies SOLs and when that happens, the counselor or adviser (one of em) trains you to take 4 or 5 APs at a time. So, alongside AP Psych, AP Environmental Science, my Monday and Wednesday would feature US History. My professor was very honest about expectations, even getting us to start classes over the summer to cover all the material due to be on the exam. We started with the Reagan Era and it didn't take long for me to realize Republicans were not for me. Then we talked about Clinton's crime bill and I wasn't too sure about Democrats either. This was two years into Obama's second term and I knew support for him in my house was fading too. As simplistic as this sounds, I really thought: if the republicans didn't care about black people, and the democrats didn't seem to care either, who did? Mixing resentment, pride and a loud mouth didn't make for the most principled Stephanie, but it did allow me to vocalize my frustrations. With Reaganomics, with capitalism, with prisons, with black boy death. Be it my teacher knowing many of the sentiments shared here or simply my being black, he asked me to read the Black Panthers' Ten Point Program. And my, oh my, did I find home there.

These were policy makers. These were the people who had the guts to demand, the power to make some changes. Fred Hampton, Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis and their inspirations in Fanon, DuBois - I found inspiration in them too. I was going to be whatever they were. Policy makers for their community. I was going to learn from them.

From there, I became incredibly elitist. But, I could also answer to the beauty of my blackness. Like many children decades before me, Black would be a political title - one of love and resistance, love in resistance. This elitism carried me into my first year of university. I glowered at anyone who admired the works of Jefferson in my Political Theory class (as if I had not done the same), I scuffed at Alexis de Tocqueville and every other white dude we were made to read. But, I wasn't acting in an antiracist framework. I was still resentful. I was still behind the glass. Now I was just shouted silently at the silk dresses and cotton scarves. But I still wanted to feel them.

Really, it wasn't until Beloved that I could begin a journey of understanding this embroiled joy of black womanhood. I realized how much I fought against my own happiness in the pursuit of a Me that I constantly tormented. As if this precariousness wasn't torment enough. Through Morrison, I was able to learn more about Angela Davis and the struggles her black womanhood had in the face of black men in her community. So many of my political thought leaders too were tormentors, liars, abusers. The men were wounded and bleeding, resented our zealous in the berries they picked. They said it was for us. We gave it to the community. They shame us for it. We bake our own pies, we feed our neighborhood and our neighborhood's resentment, our own deafening shame silences our collective ear, binds our collective feet. Once again, I tricked Me. You loved another abuser. Daydreamed of standing next to another tormentor. Admired another liar. How foolish to give your heart away again. Today, I begin to despair a bit when I think of my previous trajectory - so constantly struck by idol worship and never a Me that I had made for myself. But with Beloved - Oh my, to be so tenderly reminded that this body is mine. Just as it speaks to body(s) like mine, past and future. This heartbeat I feel expresses MY Joy, my sorrows, all mine. What a wonder it is to learn Me. She's waited so long to speak to me. I am so honored to hear her.

1 note

·

View note

Text

U.S. Congressperson and former civil rights activist/organizer John Lewis was laid to rest today. His service took place at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. The ministerial home of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 50s and 60s, Ebenezer has a long history with African people’s struggle for freedom and justice. That’s why its surreal that we find ourselves in a place today where someone like Bill Clinton can be welcomed into the pulpit at Ebenezer to offer an opinion on the correct path African people must take to achieve our forward progress. Clinton, of course, was the 42nd president of the U.S. empire. His claim to fame while being president was fooling scores of Africans into believing that he was our friend. It wasn’t until Obama was elected in 2008 that some African people stopped referring to Clinton as “our first Black president.” Underneath the superficial character presentation of Clinton existed a politician who built, along with his wife and many other opportunists a colossal industry based on imprisoning African people in this country. The Omnibus Crime bill, passed during Clinton’s tenure in 1994, proliferated incarceration rates, primarily of poor and African and/or Indigenous peoples, at record rates. And, yet, despite that clear legacy of harm caused against our people, we still invite someone like this to speak in one of our most storied and respected churches.

As a result, it should come as no surprise that Clinton used his opportunity to honor Lewis by taking a swipe at the legacy of Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael). Ture, was the organizer within the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who unseated Lewis as chairperson of SNCC in 1966, thus signaling SNCC’s turn towards much more militant politics. In Clinton’s words, this nation is in such a better place because Lewis refused to continue within SNCC after “Stokely.”

Of course, the position advanced by Clinton should surprise no one who has studied the history of this man. And, it was ironic that Clinton reminisced during his Lewis speech about “being with Jesse Jackson” because it was Jackson who was at the center of one of Clinton’s first clear indications of what type of snake he really was. During his 1992 presidential campaign against George H.W. Bush (the first Bush president), Clinton used a traditional Southern Strategy race baiting tactic to call out Jesse Jackson, who at that time was considered one of the leading civil rights leaders in the U.S. Clinton did this by making a public reference to Jackson having some type of political comradery with then so-called “Blacktivist”, rapper, Sista Souljah who had made a name for herself by calling out white supremacy in uncompromising terms. Clinton, in a direct appeal to bourgeoisie voters, primarily European ones, attacked Jackson at that time as pandering to racist African militancy.

In some ways, what Clinton said today about Kwame Ture is a continuation of those politics of respectability and accommodation. That the only right way we could ever advance our struggle for justice is by adopting positions that did not challenge the very existence of the power structure. Instead, the “responsible” way to struggle is always that of waiting, being patient, and working within the very system that keeps us oppressed. Clinton’s comments were opportunistic and designed to send a message to our people at a time when the very foundation of this system is being questioned in many ways. Clinton’s message? Don’t stray too far away from the master. Stay within this system and you will be rewarded. Resist, and you will be punished. It would be hard to find much fundamental difference between what Clinton said today and what Trump says every-day. Plus, its highly doubtful that Lewis himself would have agreed with the characterization that Clinton gave regarding SNCC’s direction in 1966. Now, I doubt there is even 2% of what Lewis believed that I agree with, but one thing I do know is that even after an initial period of distance after that 1966 election, Lewis evolved to a place where he eventually had a positive relationship with Kwame Ture. He even came and participated directly in the dinner honoring Kwame’s life shortly before Kwame made his own physical transition back in 1997.

The bourgeoisie are the spokespersons for the international capitalist/Imperialist network which is led by the U.S. And, Clinton is undoubtedly a member of the bourgeoisie class. Every U.S. president is a member of this class, including Obama. Their roles after leaving the presidential office are to continue to advance the values of capitalism, which cannot happen without also advancing white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, and all the forms of injustice that capitalism thrives on. Obama does this routinely as does Clinton. Its their class responsibility. The bigger problem is that so many of us have no understanding of history, and no desire to have an understanding, that when these people distort our history, we don’t have the tools to effectively push back. For example, if someone was to say, as Clinton did today, that SNCC, under Kwame Ture’s leadership (and later Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, formally H. Rap Brown, and then Phil Hutchings), went downhill and Lewis left to preserve some level of dignity while those wild Africans ran the organization into the ground, it would be necessary for you to have the proper understanding of SNCC history to place Clinton’s comments in the garbage can where they belong. You can do that by understanding what happened to SNCC after Kwame became the chairperson of the organization. What happened is the launching of the most recent Black power movement. The bourgeoisie want you to define that era in the late sixties by the hundreds of urban rebellions, but we employ you not to back down from that challenge. Even Dr. King knew that urban rebellions are the voice of the voiceless. In other words, when people are in pain, they lash out. When a child touches a hot stove, they don’t start singing a song and playing. Urban rebellions are reflections of this system’s inability or desire to change oppressive conditions, so people lash out. If people don’t want people lashing out, care more about people unjustly losing their lives than you do about property being attacked as a result of this glaring human contradiction. Besides that, what SNCC actually accomplished through the Black power movement was a mass awakening that we as a people have the right to exist in a manner consistent with our values and culture, regardless of how European society feels or thinks about it. Without that movement, there would be no Black Lives Matter movement. There would probably be no LGBTQ movement or women’s movements. No physically challenged movement. All of those evolved as a result of the Black power movement. And, that developing consciousness led to SNCC taking a revolutionary position against the Vietnam war. In fact, as quiet as its kept, it was SNCC that led the smash the draft movement. They were the ones who popularized the saying “hell no, we won’t go!” (a Kwame classic), and they were the first national organization at the time (with respect to the Nation of Islam) to take a national position against zionism and in support of the Palestinian people. Clearly, all of those things have advanced and evolved to become mainstream elements of the social movements you are seeing in action today and none of this could be happening without the contributions of the more militant SNCC, led in party by Kwame Ture. So, clearly, there was no moral imperative to part “from Stokely” as Clinton implied in his boring and absurd comments earlier today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sterling A. Brown

Sterling Allen Brown (May 1, 1901 – January 13, 1989) was a black professor, folklorist, poet, literary critic, and first Poet Laureate of the District of Columbia. He chiefly studied black culture of the Southern United States and was a full professor at Howard University for most of his career. He was a visiting professor at several other notable institutions, including Vassar College, New York University (NYU), Atlanta University, and Yale University.

Early life and education

Brown was born on the campus of Howard University in Washington D.C., where his father, Sterling N. Brown, a former slave, was a prominent minister and professor at Howard University Divinity School. His mother Grace Adelaide Brown, who had been the valedictorian of her class at Fisk University, taught in D.C. public schools for more than 50 years. Both his parents grew up in Tennessee and often shared stories with Brown, their only child, who heard his father's stories about famous leaders such as Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.

Brown's early childhood was spent on a farm on Whiskey Bottom Road in Howard County, Maryland. He was educated at Waterford Oaks Elementary and Dunbar High School, where he graduated as the top student. He received a scholarship to attend Williams College in Massachusetts. Graduating from Williams Phi Beta Kappa in 1922, he continued his studies at Harvard University, receiving an MA a year later.That same year of 1923, he was hired as an English lecturer at Virginia Theological Seminary and College in Lynchburg, Virginia, a position he would hold for the next three years. He never pursued a doctorate degree, but several colleges he attended gave him honorary doctorates. Brown won "the Graves Prize for his essay 'The Comic Spirit in Shakespeare and Moliere'" in his time at Williams College.

Marriage and family

Brown married Daisy Turnbull in 1927 and they went on to adopt a son together. Daisy was an occasional muse for Brown: his poems "Long Track Blues" and "Against That Day" were inspired by her.

Married for over 50 years, the second poem in Alfred Edward Housman's A Shropshire Lad was meaningful to the couple. Brown read the poem to Daisy on their wedding day and she read it to him fifty years later on their anniversary. They had one son, John L. Dennis.

Academic career

Brown began his teaching career with positions at several universities, including Lincoln University and Fisk University, before returning to Howard in 1929. He was a professor there for 40 years. Brown's poetry used the south for its setting and showed slave experiences of the African American people. Brown often imitated southern African-American speech, using "variant spellings and apostrophes to mark dropped consonants". He taught and wrote about African-American literature and folklore. He was a pioneer in the appreciation of this genre. He had an "active, imaginative mind" when writing and "a natural gift for dialogue, description and narration".

Brown was known for introducing his students to concepts then popular in jazz, which along with blues, spirituals and other forms of black music formed an integral component of his poetry.

In addition to his career at Howard University, Brown served as a visiting professor at Vassar College, New York University (NYU), Atlanta University, and Yale University.

Some of his notable students include Toni Morrison, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), Kwame Nkrumah, Thomas Sowell, Ossie Davis, and Amiri Baraka (aka LeRoi Jones).

In 1969 Brown retired from his faculty position at Howard and turned full-time to poetry.

Literary career

In 1932 Brown published his first book of poetry Southern Road. It was a collection of poems, many with rural themes and treated the simple lives of poor, black, country folk with extra poignancy and dignity. Brown's work included pieces authentic dialect and structures as well as formal work. Despite the success of this book, he struggled to find a publisher for the followup, No Hiding Place. Sterling Brown was most known for his authentic southern black dialect.

His poetic work was influenced in content, form and cadence by African-American music, including work songs, blues and jazz. Like that of Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and other black writers of the period, his work often dealt with race and class in the United States. He was deeply interested in a folk-based culture, which he considered most authentic. Brown is considered part of the Harlem Renaissance artistic tradition, although he spent the majority of his life in the Brookland neighborhood of Northeast Washington, D.C.

Quotes

"Harvard has ruined more niggers than bad liquor."

Brown's warning to Thomas Sowell, as quoted in Sowell's A Personal Odyssey (2000).

Honors

In 1979, the District of Columbia declared May 1, his birthday, Sterling A. Brown Day.

His Collected Poems won the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize in the early 1980s for the best collection of poetry published that year.

In 1984 the District of Columbia named him its first poet laureate, a position he held until his death from leukemia at the age of 88.

The Friends of Libraries USA in 1997 named Founders Hall at Howard University a Literary Landmark, the first so designated in Washington, DC.

The home where Brown resided is located in the Brookland section of Northeast Washington, DC. An engraved plaque and a sign created by the DC Commission On Arts And Humanities are featured in front of the house.

Works

Southern Road, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1932 (original poetry)

Negro Poetry (literary criticism)

The Negro in American Fiction, Bronze booklet - no. 6 (1937), published by The Associates in Negro Folk Education (Washington, D.C.)

Negro Poetry and Drama: and the Negro in American fiction, Atheneum, 1972 (criticism)

The Negro Caravan, 1941, co-editor with Arthur P. Davis and Ulysses Lee (anthology of African-American literature)

The Last Ride of Wild Bill (poetry)

Michael S. Harper, ed. (1996). The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-5045-4. (1st edition 1980)

The Poetry of Sterling Brown, recorded 1946-1973, released on Smithsonian Folkways, 1995

Mark A. Sanders, ed. (1996). A son's return: selected essays of Sterling A. Brown. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-55553-275-8.

Old Lem (Poem)

Old Len was put to music by Carla Olson with the permission of Sterling Brown’s estate. The resulting song is called Justice and was recorded by Carla backed by former member of The Rolling Stones Mick Taylor and former member of the Faces Ian McLagan along Jesse Sublett on bass and Rick Hemmert on drums.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE FBI’S WAR ON BLACK BOOKSTORES

By Joshua C Davis

In the spring of 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover announced to his agents that COINTELPRO, the counter-intelligence program established in 1956 to combat communists, should focus on preventing the rise of a “Black ‘messiah’” who sought to “unify and electrify the militant black nationalist movement.” The program, Hoover insisted, should target figures as ideologically diverse as the Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture), Martin Luther King Jr., and Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad.

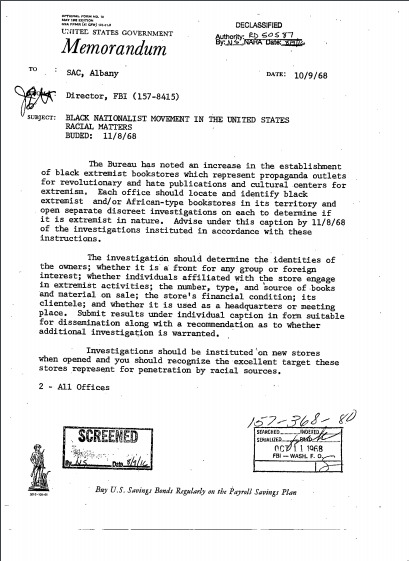

Just a few months later, in October 1968, Hoover penned another memo warning of the urgent menace of a growing Black Power movement, but this time the director focused on the unlikeliest of public enemies: black independent booksellers.

In a one-page directive, Hoover noted with alarm a recent “increase in the establishment of black extremist bookstores which represent propaganda outlets for revolutionary and hate publications and culture centers for extremism.” The director ordered each Bureau office to “locate and identify black extremist and/or African-type bookstores in its territory and open separate discreet investigations on each to determine if it is extremist in nature.” Each investigation was to “determine the identities of the owners; whether it is a front for any group or foreign interest; whether individuals affiliated with the store engage in extremist activities; the number, type, and source of books and material on sale; the store’s financial condition; its clientele; and whether it is used as a headquarters or meeting place.”

Perhaps most disturbing, Hoover wanted the Bureau to convince African American citizens (presumably with pay or through extortion) to spy on these stores by posing as sympathetic customers or activists. “Investigations should be instituted on new stores when opened and you should recognize the excellent target these stores represent for penetration by racial sources,” he ordered. Hoover, in short, expected agents to adopt the ruthless tactics of espionage and falsification they deployed against civil-rights and Black Power activists, and now use them against black-owned bookstores.

Hoover’s memo offers us a troubling glimpse of a forgotten dimension of COINTELPRO, one that has escaped notice for decades: the FBI’s war on black-bookstores. In addition to Hoover’s memo, I uncovered documents detailing Bureau surveillance of black bookstores in a least half a dozen cities across the U.S. in conducting research for my book, From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs. At the height of the Black Power movement, the FBI conducted investigations of such black booksellers as Lewis Michaux and Una Mulzac in New York City, Paul Coates in Baltimore (the father of The Atlantic national correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates), Dawud Hakim and Bill Crawford in Philadelphia, Alfred and Bernice Ligon in Los Angeles, and the owners of the Sundiata bookstore in Denver. And this list is almost certainly far from complete, because most FBI documents pertaining to currently living booksellers aren’t available to researchers through the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).