#west virginia penitentiary

Text

"The prisoners were permitted to smoke pipes, but were not supposed to keep matches. In order to enable them to light up, a guard made the rounds with a lighted torch each evening after the inmates were locked in their cells. The prisoners desiring a light were supposed to have a piece of paper rolled up into a taper, and placed on the cell rail, ready to be lighted quickly by the torch. One lighting was all they got.

Some of the prisoners often improvised their own lighting system by passing a cotton string, burning at one end, from cell to cell. This nimble fagot sometimes made the rounds until the retirement call was sounded.

Some of the prisoners succeeded in lighting their pipes by the use of pieces of flint and steel, which they kept hidden in their bunks or on their person.

Pranks and games of various kinds were often played surreptitiously by the inmates. In order to detect the approach of the guards walking noiselessly, with their shoes equipped with rubber soles and heels, they kept themselves supplied with small mirrors. Set at proper angles, the guard could be seen a cell-block away. Safeguarded in this manner they often indulged in games of dominoes and checkers. When the players were confined in adjoining cells, they executed the moves of the game by means of broomsticks, the pieces being shoved about on the floor on the outside of the cells.

A certain prisoner born in a foreign country was working in the prison bakery, where pies were being baked, supposedly for the guards, but which could be bought by prisoners at fancy prices, if done on the quiet. The foreigner, not well versed in American ways, and preferring to take a hint rather than the consequences, became the dupe of a scheming patient, lounging outside of the hospital. With black ink he printed on a piece of paper a demand that a pie be left on the bakery steps at a certain hour, or else his graft would be exposed. For signature the message bore the ominous sketch of a large black hand. The ruse worked perfectly, and, at the designated hour, the pie was ready and waiting on the bakery steps.

There were not very many lawyers in prison, not as many, in proportion, as from most of the other professions; but there was one barrister in the penitentiary who claimed that he was there on account of his political ambitions, and the duplicity of a fellow member of the bar.

He said that he had announced his candidacy for the office of prosecuting attorney of his county; then, he explained, the lawyer who was already holding the office, and who was a candidate for re-election, trumped up a charge against him, landed him in prison, and succeeded in having himself re-elected.

“When these prosecutors get after you,” he said, “they are like a pack of hounds. When one yelps, ‘Here’s the hot trail,’ they all fall in, and your hide is bound for the tan yard.” He may have been too severe on his fellow barristers; but he added, “If you make a mistake, you go to prison. If your attorney makes a mistake, you go to prison. If the judge or the jury makes a mistake, you go to prison—so there you are.”

“Well,” questioned an unsympathetic prisoner, “you wanted to be a prosecutor and devote your life to sending other people to jail, didn’t you?”

“Yes, I did then, but never again,” replied the lawyer.

It all depends on the point of view. There would hardly be room in the prisons for all the [political] candidates these days.

A nutty prisoner, with a propensity for playing pranks, on one occasion caused a good deal of merriment to a lot of prisoners at the expense of a green guard. This inmate, known as “Steed,” had succeeded in convincing the officials that he was mentally unbalanced. Being considered harmless, he was assigned the task of carrying messages and orders from the office to others within the grounds. This work gave him the opportunity of helping to initiate the newly appointed and inexperienced guards.

Having delivered a number of messages to the new guard, and having observed that the instructions were being carried out without question, the nit-wit proceeded to give orders of his own. He secured a long pole, to one end of which he tied a bunch of cloth, and delivered it to the guard with the statement that the warden wanted him to dust off the wire screens in the second story windows of the prison buildings.

The unsuspecting guard worked industriously for more than an hour at this bogus task, while the wag was concealing his glee with great difficulty, and much to the amusement of the many prisoners, who were always keen to laugh at the victim of a practical joke, especially if the victim was a guard.

Having been tipped off by another guard, and realizing that he was the butt of one of Steed’s jokes, he broke the pole into pieces and gave the prison jester a merry chase as he hurled the remnants of the broken pole at his empty head.

Even jokes at the expense of the warden were highly relished. The story went the rounds that one day a reform worker, while visiting the prison, was perturbed by the downcast attitude of one of the men she found.

“My poor man,” she said to him, “‘what is the length of your term?”

“Depends on politics, lady,” replied the melancholy one, “I am the warden.”

The ancient practice of using articles of merchandise instead of money as the medium of exchange was quite common in this state prison. The rule forbidding the inmates to have money made the practice necessary.

The men were permitted, at times, to buy cans of tobacco and other articles, to be paid for with funds to their credit at the prison office. A number of them made it a practice to keep on hand a number of these cans of tobacco, and then when they desired to purchase something possessed by some other prisoner, the value was fixed at so many cans of tobacco instead of a price expressed in dollars and cents. In this manner, when the purchase was made, the cans of tobacco were paid out and passed current the same as if they had been coins of the realm. Necessity in this case, as in many others, became the mother of invention.

Christmas is the one great day of the year in the penitentiary. Then, if ever, the convicts are treated with some degree of respect and decency. The Christlike spirit penetrates even the lonely prison walls on this universal festal occasion. On that day at least one good meal is served.

For months in advance, the prisoners looked forward to the coming of Christmas, and talked about it for months afterwards. Some leniency was practiced then in the receipt of boxes and presents from the outside, and it was surprising and gratifying to observe the generosity with which those fortunate enough to receive boxes, shared their contents with those not so favored.

If one observed the dining room in August or September he need not be surprised to see the decorations placed there the previous Christmas, and would understand that nothing worth while had taken place since. The monotonous life of the men entombed in dismal prisons is brightened by this brief gleam of Christmas cheer, and helps to lighten the burdens during the whole dreary year.

Penal servitude, with all its blighting effects, does not seem to dampen the spirit of patriotism in the breasts of prisoners. When America entered the World War, the men in the penitentiary lost no time in offering their services in any capacity in which their country might wish to use them. Those who had means at their command were liberal buyers of Liberty Bonds. In times gone by, men convicted of crime were given the privilege of serving as soldiers, and gave a good account of themselves.

...

Should you ever be sentenced to the penitentiary be wise enough to choose first to be a writer, an editor, or a reporter. They seemed to get all the breaks when the really desirable jobs were handed out.

The reason for this preferment remains unexplained, but, should any of them care to write, either then or later, there is at hand an abundance of live material scintillating with the motives and mockeries, the miseries and tragedies of life as in no other place.

This prison, like most others, had a printing shop, and many an undiscovered Milton lived to see his masterpieces find their way into the prison paper. A volume might be written about prison poetry, or filled with so-called poetry written by men behind prison bars; some of which was not so bad, much of it was humorous, very little of it was pessimistic, or tinted with the “prison blues.”

- Earl Ellicott Dudding, The Trail of the Dead Years. Edited by William Winfred Smith. Huntington, West Virginia: Prisoners Relief Society, 1932. p. 86-91

#life inside#west virginia penitentiary#moundsville#sentenced to the penitentiary#west virginia#american prison system#prisoner autobiography#history of crime and punishment#research quote#prison conditions#trail of the dead years#reading 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best birthday ever! Ghost hunt at the moundsville penitentiary with my girlfriend and best friends!

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

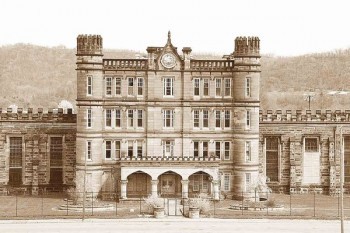

One week from today I'm going to Moundsville, West Virginia to spend two nights in lockdown inside the old WV State Penitentiary!

Look at how HUGE it actually is 😮

.

Tag urself I'm 100% Shane 😃

.

#I ain't afraid of no ghost!#Haunted#Ghosts#Paranormal Investigation#Moundsville Penitentiary#West Virginia

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spooktober Haunted Places: Moundsville Penitentiary in Moundsville West Virginia #hauntedplaces #MoundsvillePenitentiary #moundsville #WestVirginia #moundsvillewestvirginia

#haunted places#moundsville#Moundsville Penitentiary#west virginia#moundsville west virginia#Spooktober#Halloween#october

0 notes

Text

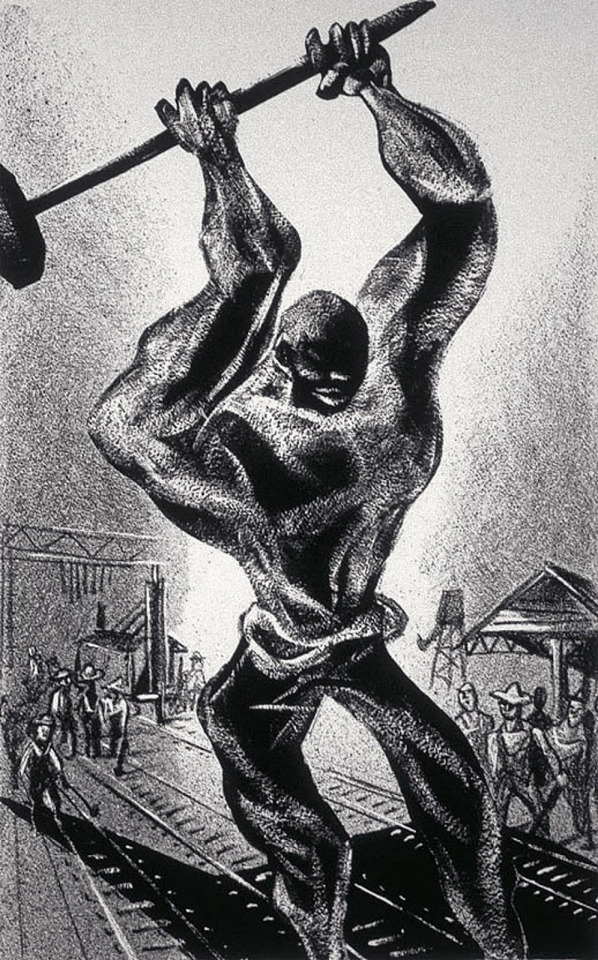

Died With a Hammer in His Hand: Unpacking the Myth of John Henry

“John Henry said to his captain:

‘You are nothing but a common man,

Before that steam drill shall beat me down,

I’ll die with my hammer in my hand.’”

— “John Henry, the Steel Driving Man,” recounted by W. T. Blankenship

John Henry is one of America’s most well-known mythic heroes, immortalized in song, statue, postage stamp, and multiple movies (including a 2000 Disney animated short film which I vividly remember watching in elementary school). But if you’re unfamiliar with the legend, here’s a brief summary.

John Henry was a freed slave who found himself working for a railroad company in the years following the Civil War as a steel driver. His job was to drive a steel spike into rock so that dynamite could be placed in the resulting hole, thus opening up a tunnel through the Appalachians.

John Henry was the best on his crew, and he took pride in his work—so when a white salesman brought in a steam-powered drill, claiming that it could drill better than any man, he decided to challenge that claim. Henry entered into a contest with the machine to see who could carve out the deepest hole in the mountain in a single day.

His victory cost him his life.

Henry’s wife—sometimes named Polly Ann, sometimes named Lucy, sometimes not named at all—went to visit him on his deathbed that evening. In many versions of the ballad, Henry’s last words are a request for a glass of water. In other versions, he asks his wife to be true to him when he’s dead, or to do her best to raise their son. Many accounts say that he’s buried by a railroad, where “Every locomotive come roarin’ by, / Says there lays that steel drivin’ man” (lyrics from Onah L. Spencer).

Bronze statue of John Henry near Talcott, West Virginia, sculpted by Charles Cooper.

The general consensus among historians now seems to be that the ballad of John Henry is one such legend that has its roots in historical fact, although the particulars are long obscured by the centuries that have since passed. Henry was born into slavery in the 1840s or 50s, either in North Carolina or Virginia (some accounts of the ballad lend credence to the latter claim). As for how John Henry found himself working for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway company, University of Georgia history professor Scott Reynolds Nelson posits in his book Steel Drivin’ Man that the man was sentenced to ten years in a Virginia prison for theft at only nineteen years of age, and that he was among many prisoners leased out by the state for labor.

Did you know that the 13th Amendment makes an exception for slavery which is used “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted”? (This practice continues to this day, and has become an industry worth tens of billions of dollars. Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola or simply “The Farm,” is a good place to begin if you’re wanting to look into chain gangs further.) John Henry the legend was a free worker who took on the backbreaking, often dangerous work of railroad labor under his own power and could demand any wage for his work, but John Henry the man may have lived and died in neoslavery.

Speaking of Henry’s death, most retellings of the myth say that he died of sheer exhaustion. Some add in the detail that it was his heart that gave out because he worked himself too hard. However, alternate theories have been proposed for how the man died. Some historians say it was a stroke that killed him, while others posit silicosis.

It’s this latter hypothesis which I find most intriguing. For those who aren’t familiar with it, the American Lung Association describes silicosis as “a lung disease caused by breathing in tiny bits of silica, a common mineral found in sand, quartz and many other types of rock.” It’s been an occupational hazard for construction workers since, well, the time of John Henry. What I find interesting are the implications for the narrative if the real Henry died of silicosis. In the folk ballad, Henry causes his own death by working himself too hard. On the other hand, the ones at fault if the man died of silicosis would be his employers—the ones responsible for the dangerous conditions he worked in.

So why would John Henry’s cause of death change during the transition from fact to legend?

The answer, as with many other fictionalized accounts of historical events, is that it simply makes for a more effective story. But not just that—a more effective message. So what might the ballad be trying to tell those who listen to it?

First, let’s think about who this song was sung by and for. The ballad of John Henry is a work song, its rhythm meant to help railroad workers stay and strike in sync, in the same way a drumbeat helps soldiers march in step. It’s been sung by railroad workers, miners, construction workers, chain gangs, and country musicians. At its core, then, the ballad is a song of and for the American working class—specifically those people doing the same sort of backbreaking physical labor as John Henry himself. Many of these laborers would have been Black, and likely former slaves—especially when it came to Southern chain gangs. (See my above note about how American slavery was only mostly abolished, and then think about why the U.S. has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. . . but I digress.)

An oil painting of John Henry by Frederick Brown.

We’ve established that John Henry is a hero for working-class Americans during the time of the Second Industrial Revolution. But what sort of hero is he? Is he like Achilles, a paragon of his country’s values and an example for the audience to aspire to? Or is he an Icarus, a cautionary tale sung so the audience won’t repeat his mistakes?

The answer depends on who’s telling the story.

Onah L. Spencer is the source for one version which emerged from a Black community in Cincinnati, Ohio. When he recounted the lyrics to Guy B. Johnson for the latter’s 1929 book John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend, he also stated that the song was used to motivate workers: “. . . if there was a slacker in a gang of workers it would stimulate him with its heroic masculine appeal.”

In cases such as Spencer’s crew, then, John Henry’s death is presented as glorious, and Henry is seen as admirable for working so hard that it kills him. Here, he’s a good example. Taken to the extreme, the Achillean Henry encourages fellow workers to follow in his footsteps—to keep pushing themselves harder and harder until they finally keel over.

This message doesn’t benefit the workers passing it along; it benefits the employers profiting from their labor. This, I think, is where the story blurs the line between myth and propaganda. And while the ballad of John Henry certainly isn’t singlehandedly responsible for the American tendency to overwork ourselves, it does reflect our attitudes about work in a way that’s worth unpacking. To me, this reeks of the Puritan work ethic. The belief was that you had to be working as often as you could; if you didn’t, the devil would be able to influence you. The Puritans were one of America’s foundational cultural influences—of course those values would have influenced the ballad of John Henry.

Henry is a hero because he worked himself to death. If we see him as a good example, what does this say about the effects that capitalism has had on American attitudes? About the internalized belief that our worth as humans only comes from what we can contribute to the economy? Why do we see death from exhaustion as a fitting end for a former slave?

Then again, maybe we’re not supposed to.

A lithograph of John Henry, from the series American Folk Heroes, by William Gropper.

Remember how I noted earlier that many of the laborers who first sang Henry’s ballad would themselves have been former slaves? It’s important because there’s a long history of American slaves using work songs as a tool of resistance against their oppressors, and these Black laborers—these “freed” slaves—would have carried that tradition with them into the Second Industrial Revolution.

The ballad of John Henry, then, might have been sung with the intent of helping other workers survive the brutal conditions on the railroads. Here, Henry becomes an Icarus—a warning of what happens if you push yourself too hard. One version of the ballad recorded by Edward Douglas of the Ohio State Penitentiary contains lyrics which suggest that not every Henry was meant to be emulated.

“John Henry started on the right-hand side,

And the steam drill started on the left.

He said, ‘Before I’d let that steam drill beat me down,

I’d hammer my fool self to death,

Oh, I’d hammer my fool self to death.’”

Don’t do what John Henry did, this version warns the audience. Be wiser than he was. Don’t push yourself quite so hard. Think of the people you’d be leaving behind if you’re not careful.

Perhaps even the creation of this mythos was an act of defiance in and of itself. At this point, I think it bears mentioning that I myself am not Black and can only hypothesize based on what I’ve heard from people who are, but I see something radical in the act of raising up one of your own as your hero rather than venerating the people you’ve been told are superior to you.

Remember, John Henry’s contest was versus a white man’s machine. It costs him everything, but he triumphs over the expectations of that steam drill salesman and proves his worth as a laborer and a person. John Cephas, a blues musician from Virginia who was interviewed by NPR for a report on John Henry back in 2002, had this to say of the myth:

“It was a story that was close to being true. It’s like the underdog overcoming this powerful force. I mean even into today when you hear it (it) makes you take pride. I know especially for black people, and for people from other ethnic groups, that a lot of people are for the underdog.”

Americans love underdog stories. Our own national origin myth is one! John Henry’s assertation of power and skill, the ballad’s declaration that Black people have the right to be proud of themselves too. . . no wonder this myth has resonated with so many people. No wonder it’s survived for a century and a half.

In this light, then, John Henry once again becomes a hero for us, the audience, to emulate. In the fight against oppression, endurance like Henry’s becomes key. Justice is almost never won quickly. The odds stacked against us may seem impossible, but it’s worth trying anyways, even if we have to fight to our dying breaths.

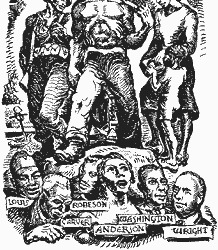

Artwork of John Henry as a defense worker by James Daugherty.

John Henry has meant and been many things to a lot of people in the past two centuries. A representative of capitalist exploitation, a cautionary tale for workers, an inspiration to oppressed people in America, even a communist icon—but I’d like to take a moment to talk about what his story means to me. It’s not something I’ve seen discussed in my research, and I think it’s worth exploring.

John Henry reflects fears of workers during the Second Industrial Revolution who saw how technology was evolving—how machines were being created that could do their jobs not just faster, but cheaper, because you don’t have to pay a machine like you would a person. They feared that they would be replaced, and that they would be left destitute while their former bosses grew richer and richer. And despite the centuries between us, this is a fear that I can understand.

Often, I feel it myself.

As an artist existing in online spaces during this new influx of AI-generated “art” and writing, I have witnessed many fears that we will be replaced by AI. Yes, there is a certain human quality to art that a generative learning model cannot replicate, but who’s to say that the much-vaunted free market will care? We can hope that art as a profession will survive, but we just don’t know.

In John Henry’s struggle, I see my own. In the steam drill salesman, I see tech bros on the platform formerly known as Twitter showing off their latest batch of beautiful, hollow, AI-generated “art.” I see John Henry’s passion, his pride, his triumph.

And I see hope.

By his life and death, the mythic John Henry reassures me that human beings aren’t so easy to replace after all. He tells me that machines can be defeated. That one day, my vindication as an artist and writer will come, and the world will see our worth.

The ballad of John Henry has endured like a mountain for a hundred and fifty years, and I hope it will survive for hundreds more—that John Henry’s hammer will continue to ring true throughout the ages. But in the midst of American mythos, it’s important not to lose sight of the historical facts behind it. Legends are interesting and inspirational and wonderful, but the real stories have something to tell us, too.

Don’t forget to listen.

Works Cited

American Lung Association - Silicosis

Ballad of America - This Old Hammer: About the Song

Constitution of the United States - Thirteenth Amendment

Encyclopedia Britannica - John Henry

Flypaper by Soundfly - The Lasting Legacy of the Slave Trade on American Music

Folk Renaissance - John Henry: Hero of American Folklore

How Stuff Works - Was There a Real John Henry?

ibiblio.org - John Henry: The Project

National Park Service - The Superpower of Singing: Music and the Struggle Against Slavery

NPR - Present at the Creation: John Henry

NPR - Talk of the Nation: The Untold History of Post-Civil War ‘Neoslavery’

PBS - Mercy Street Revealed Blog - Singing in Slavery: Songs of Survival, Songs of Freedom

Prof. Scott Reynolds Nelson - Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend

World Population Review - Incarceration Rates by Country 2024

#john henry#american mythology#analysis#essay#black history month#ari speaks#hi I wrote this for my english class and I felt compelled to share it here

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh the other bit that I love that made it on screen is when the hangman comes home to his wife and children and compulsively washes his hands over and over.

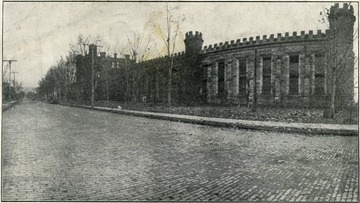

Grubb grew up in and around Moundsville, West Virginia. Moundsville is a prison town, home to one of America’s oldest penitentiaries. it's this horrible old complex that looks like a fucking castle. and the violence of the prison industrial complex looms over all of his writing like a ghost

I can’t imagine what growing up in this small poor town during the depression, being kicked out of your family home while this fucking thing stands tall and continues to publicly hang prisoners outside would be like as a kid. I’m still really mad about this really dismissive 'bio' I read years ago that was clearly written by someone who hated Grubb and his leftism

anyway in this scene the hangman is washing his hands and talks about how he wishes he didn’t quit his job in the mines, which would’ve been a death sentence (especially because he’s an older man) because he is so pained by this job. his job options are execute his neighbors for the state or die in a mine collapse and leave his wife and children hungry and that’s it

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

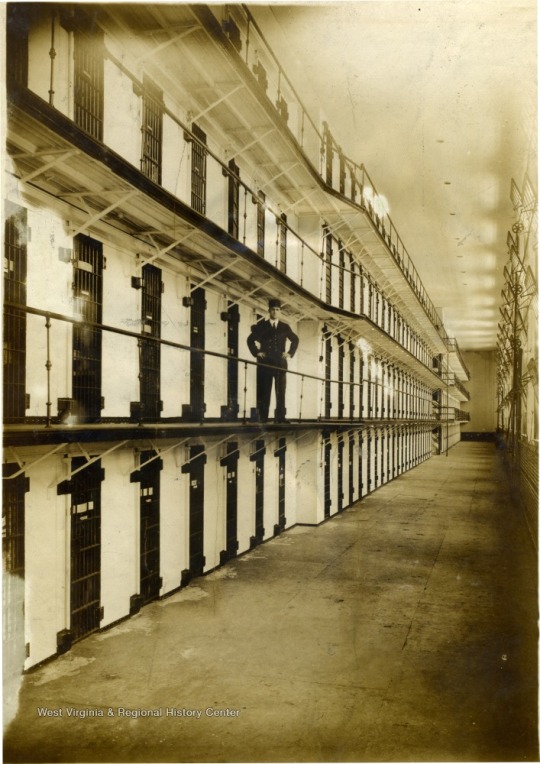

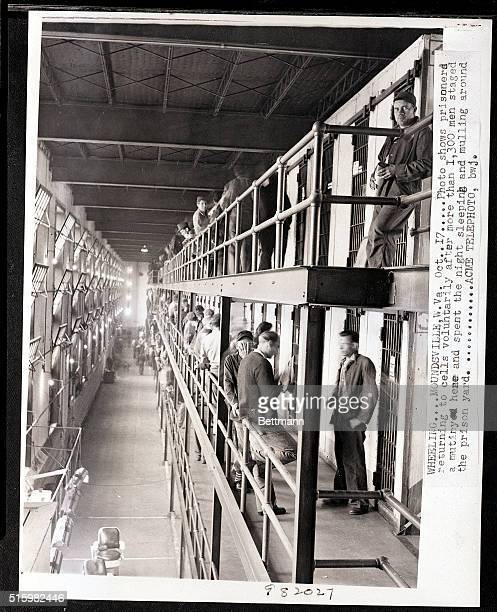

Moundsville West Virginia Penitentiary

Maximum Security / Death Row Cell Block

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not saying Shane and Ryan should visit Moundsville WV, but they should definitely visit Moundsville, West Virginia. They have not one but TWO places in which they could do ghost files investigations and they are right across the street from one another. 1. The old West Virginia Penitentiary, where they still have a rope up at one of the entrances where they hung people. And 2. A literal Native American burial mound

#ghost files#we are watcher#watcher entertainment#shane madej#ryan bergara#ryan beef boy bergara#ghost investigation#possible future investigation????#I’m begging you#shane and ryan#Puppet History#too many spirits#mystery files#watcher#big apple steve#steven lim

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Sean McKinnon ( Whitey Bulger murder suspect ) Wiki, Bio, Age, Crime, Arrest, Incident Details, Investigations and More Facts

Sean McKinnon Biography Sean McKinnon Wiki

A man accused of involvement in the killing of James "White" Bulger in prison has said it's no secret an 80-year-old crime boss will appear there.

"Everyone knew it was coming," Sean McKinnon said in an interview with NBC News.

The Boston mobster was found dead in a USP Hazelton maximum-security prison on October 30, 2018, just hours after he was transferred to the West Virginia state penitentiary.

Bulger was transferred to the facility after threatening a nurse at his former Florida jail.

Whitey Bulger murder suspect says 'everybody knew he was coming' to their prison: Sean McKinnon, speaking in a jailhouse interview, said word of Whitey Bulger gangster's transfer to their prison had spread well before his arrival. via NBCNews https://t.co/3Zp8k6GB0m

— Jeffrey Levin 🇺🇦 (@jilevin) September 10, 2022

The 89-year-old mobster, in a wheelchair, with heart problems and high blood pressure, was "severely beaten" by more than one inmate shortly after his arrival.

Photius "Freddy" Jess, 55, and Paul J.D. Cologero, 48, both with organized crime ties, killed Bulger while McKinnon acted as an observer, prosecutors say.

McKinnon, who was originally jailed for stealing firearms and selling them as drugs, says he is an innocent man.

"I'm an innocent man stuck in the wrong things," he told the network.

Read the full article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Seeing how greatly interested the convicts were in the Christian Herald, I obtained permission from the warden to secure their subscriptions for it. Several hundred prisoners became subscribers and regular readers. In many instances the influence of this religious journal upon the convicts became very noticeable.

Among the subscribers was a full-blooded young Indian, of the Mohawk tribe, and known as “Indian Joe.” He was accused of having killed a man in a riot among the miners in the coal fields. Although he steadfastly maintained his innocence of the crime for which he was sentenced, he took his imprisonment with true Indian stoicism.

In his cell he kept an unique home-made calendar. On a large piece of cardboard he had drawn a great number of circles, with twelve circles in a row. Each circle stood for a moon, or month, and each row represented a year. It was the Indian calendar. As time elapsed, month by month, he marked off a circle. When all the moons on his calendar had waxed and waned, and were marked off, his long sentence would be at an end. It was a joyous ceremony to him each month when he marked off a passing moon, bringing him one step nearer to ultimate freedom.

Indian Joe was greatly pleased and perplexed as he read the Herald—pleased with the ideals of Christian living as it was taught, and perplexed by the many un-Christian acts of life as it was lived.

I was very much interested in the reactions of his alert and practical mind. One day, while talking with him about such matters, he asked me, ‘‘How come Christian folks send missionaries to China, and keep innocent white men and Indians locked up in pen right here home?”

Needless to say I was puzzled about what kind of an answer to give him, but, finally, I explained that Christian people did not know that these prisoners were innocent.

His practical mind flashed back a question immediately. “Then why no tell them?” he asked sincerely."

- Earl Ellicott Dudding, The Trail of the Dead Years. Edited by William Winfred Smith. Huntington, West Virginia: Prisoners Relief Society, 1932. p. 100-101

#life inside#west virginia penitentiary#moundsville#sentenced to the penitentiary#west virginia#american prison system#prisoner autobiography#history of crime and punishment#research quote#prison conditions#trail of the dead years#reading 2024#religion in prison#indigenous people#american indians#wrongfully convicted#christian mission#mohawk

1 note

·

View note

Note

I know it's been 2 days but yes WV is an east coast state despite not having a coastline. Or at least the eastern panhandle is since it is so interconnected with Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Southern and central WV doesn't feel very east coast but you don't want to visit much of southern WV anyway since it has basically nothing for tourists to see other than New River Gorge National Park (there is also the WV Mine Wars Museum on the Kentucky border). Central WV has some really cool places to visit but they are often difficult to get too like Helvetia. The northern panhandle has The Penitentiary and the mothman festival + a very int. Most of the cool things are on the eastern panhandle like Harper's Ferry, Seneca Caverns, Shepherdstown, and a bunch of Civil War sites and museums. The panhandle is really interconnected with the actual coast states and historic places in Maryland, like Antietam battlefield, have things to see in West Virginia connected to them.

Sorry this is so long and possibly not super coherent, I grew up all over WV before moving to New England and I genuinely think people should include it in their travels since it has such a fascinating history.

No worries. Thanks.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm in the prison yard at Moundsville Penitentiary and I just heard clear footsteps on the pavement by the bus that's parked between the chapel and guard tower 4. There's no one out there. 🤔

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Echoes of Despair: Unveiling the Haunted History of Moundsville Penitentiary

Join us for a chilling exploration of the dark history of Moundsville Penitentiary in West Virginia, an awe-inspiring symbol of America's penitentiary legacy. This classic haunted location beckons to those curious about the paranormal, revealing a tapestry of desperation woven within its walls.

You can also win a Gift Card By Reading Our daily Content !!!!

Read The Whole Article Find Special Words, and Sign UP!! AND Collect Points and You can Also Win $1000 worth of gifts.

To read the Article Visit :

0 notes

Text

Myth Busting – Part 3 – A Murdered State Trooper

(Author’s Note: This is the third installment of myth-busting legends concerning the West Virginia Penitentiary. This chapter concerns the true facts behind the murder of W.Va. Trooper Philip Kessner.)

It is commonly thought murderer Ronald Turney Williams killed West Virginia State Trooper Philip Kesner during an escape on November 7th, 1979 from the penitentiary.

This is not true as court documents and interviews from the actual escapees prove otherwise. It must be noted that this is not an attempt to make Williams look good in any way as he is a cold blooded, cold hearted, egotistical murderer. While Williams murdered two other people, Beckley Police Officer David Lilly and John Bunchek, he did not kill Trooper Kesner. This narrative will describe the events of the escape and reveal the true killer.

On Wednesday, November 7th, 1979, Harold Gower approached Donald Layne and told him Ronald Williams and Jack Hart wanted to talk to him and it was very important. They said, “Everything will be ready in fifteen minutes.” A little before 8 p.m., inmates started casually congregating outside of the command post.

Correctional Officer John Villers served at the penitentiary for many years and was six feet tall and weighed 140 pounds. Gray hair covered his head as he was 61 years old at the time of the escape of the prisoners. The inmates and other correctional officers affectionately referred to him as “Pop.”

Williams, Hart, and Layne knew they could overcome Correctional Officer Villers as he suffered from heart and breathing problems. The plan was to subdue Villers and prop open the door of the control cage. If the metal door to the control cage was locked, Officer Villers might have been able to halt the exodus of escapees.

Williams and Hart’s plan commenced once Correctional Officer Villers was distracted. At that point, Hart was the only one who possessed a weapon as he carried the smuggled .32 caliber pistol. Hart served as a barber for the prison and the barber shop was located just east of the Command Post on the other side of the 98 Corridor.

It was common for a prisoner to work as the barber to cut the hair of the other prisoners and he would keep the hair searing tools in the Command Post. Because Hart was the barber, he had open door access to the command post.

Forty-one years old Correctional Officer Jerry Daff was five feet eight inches tall, weighed 130 pounds, and worked at the penitentiary for a few years. He was making sure the penitentiary count was correct when he was startled by the shaking door.

Hiding the gun underneath a sweater vest pullover, Hart rattled the metal electronic door leading from the 98 Corridor to the Command Post. Layne heard the snapping click as it opened as Officer Jerry Daff pushed the circular button to activate the opening of the door at 8:05 p.m. Hart hastily entered first and stuck a smuggled .32 caliber pistol at Correctional Officer Daff’s head and barked at him, “Don’t make any moves or I’ll blow your head off.”

Inmate William Burd was cleaning the Command Post when the inmates first entered and was disconcerted by the sudden movement. He reported he saw Hart pull up his sweater vest, grab the .32 caliber gun from his leather belt, and place it firmly to Officer Daff’s head.

At this point, Williams and several inmates flooded into the Command Post from the 98 Corridor. Harold Gower was one of them and he was holding a large, wooden broomstick in his hands to prop open the door so others could escape. As Hart held Officer Daff hostage with the loaded gun, Donald Layne demanded Officer Daff tell them what key opened the command center door. This door was the last exit leading to the visiting waiting room that stood between them and the front door.

Officer Daff stated, “I can’t tell you which key it was.” At this point, Donald Layne brandished a knife and pressed it firmly on his throat exclaiming, “Let’s kill him.” Fearing for his life, Officer Daff showed the inmates the key that unlocked the door granting them another step toward their freedom.

Without hesitation, the key hanging on a metal nail behind a desk was snatched.

Ronald Turney Williams was far from a model prisoner in the Moundsville prison.

Stop That Car!

Hart continued to hold the gun upon Officer Daff as Layne unlocked the steel door. With this obstacle overcome, Jimmy Collins and Thomas Burton rapidly rushed to the elevated gun cage where Correctional Officer John Villers was stationed. The gun cage door should have been closed and locked, but when it was secure, there was terrible ventilation which made it hard for the officers to adequately breathe.

Burton forcefully kicked the boxed gun cage door wide open granting full access to their future freedom. Correctional Officer Villers attempted to grab his penitentiary-assigned service pistol out of its leather holster, but Jimmy Collins harshly grabbed his hand and prevented him from doing so. Collins reached in and tightly clenched the .38 caliber pistol and started pushing the control buttons that opened the front door exiting the penitentiary. Correctional Officer Villers was dragged out of the gun cage and placed in front of the group of fleeing inmates.

There was a lengthy span of time where all the exits of the new administration building were completely open and hundreds of inmates could have escaped from custody of the maximum-security prison. With the doors open, inmates David Worley, Harold Gower, John Keenan, Shirley Adkins, and Williams ran out onto Jefferson Avenue, the road that runs from north to south and is one of the main streets of Moundsville.

Hart continued to hold Correctional Officer Daff at gunpoint as they made their way to the concrete stretching sidewalk that runs parallel to the prison with Correctional Officer Villers being dragged along as well.

The jumpy inmates started yelling at the correctional officers. “Where is your car?”

Correctional Officer Daff responded: “I don’t have a car.”

Layne threateningly retorted, “You son of a bitch, you better have a car.”

Other inmates continued badgering him. “Where’s your car?”

At 8:15 p.m., a hardtop 1977 Plymouth, two doors, painted blue on the bottom and white on the top part, Sport Fury drove south on Jefferson Street in front of the prison. One of the prisoners excitedly yelled, “Stop that car!” The escaping mob ran toward the trajected path of the car and forcefully shoved Correctional Officer Daff in front of the moving vehicle.

Inside the car were a young couple whose identity were not known at the time. The driver, who was West Virginia State Trooper Philip Kesner, vigorously stomped his foot on the brake to avoid striking and seriously injuring Sgt. Daff. The occupants of the car were he and his wife, Connie, as they visited friends and were now returning home. Due to State Trooper Kesner’s skillful maneuvering, he managed not to hit Correctional Officer Daff.

As he was violently thrusted toward the Fury, Correctional Officer Daff landed on the front left fender of the automobile. Mrs. Kesner remembered that a large group of men started running toward the car and then Hart savagely jerked the driver’s side door open.

State Trooper Kesner, a physically fit and strong man, was rigidly gripping the steering wheel tightly to thwart their devious plans and Mrs. Kesner heard one of the inmate’s spew, “Don’t f*** with him, kill him.”

Hart and Collins were the first inmates to grab hold of State Trooper Kesner and then Layne took hold of his right arm to assist in his violent and abrupt removal.

West Virginia State Trooper Philip Kesner during an escape on November 7th, 1979.

Double Cross

Correctional Officer Daff reported that Jack Hart and Donald Layne jerked State Trooper Kesner out of the car by grabbing his coat and sadistically spewing, “Get the f*** out of the car.”

In cold blood, State Trooper Kesner was pointblank shot by Jack Hart.

Harold Gower was the first inmate that entered the Kesner’s vehicle after Officer Kesner was forcibly removed. He briskly turned toward Mrs. Kesner and snapped, “Get out of the car, get out of the car.” Mrs. Kesner tried to exit as fast as she could, but it wasn’t fast enough for Gower. He grabbed the back of her head and with a fistful of her hair, shoved her out of the car. She landed face down upon the rigid concrete surface of Jefferson Avenue. Hart, Burton, Morgan, Collins, and Layne piled into the car with Gower.

Even though he was shot, State Trooper Kesner quickly rose to a standing position outside of his hijacked car. He swiftly drew a .38 caliber revolver from his concealed ankle holster and shot six rounds pointblank into the hijacked vehicle. Gunshots rang out and breaking glass echoed through the air. During this chaotic time, Mrs. Kesner ran to safety near the rear of the car. State Trooper Kesner waited for his wife to safely evade the line of fire that was to begin.

Although he was profusely bleeding, State Trooper Kesner’s thoughts were those of saving his wife from the vicious escapees. His last heroic act was to protect his wife and to fulfill his sworn duties as a law enforcement official.

Several shots by State Trooper Kesner penetrated the metal exterior of the vehicle’s door. Two bullets struck houses across the street and one of the shots made its way into the body of Jimmy Collins. As Donald Layne frantically dove over the front seat of the car into the back seat, he was also struck in his left side by the .32 caliber revolver. This was the gun that the prisoner, Jack Hart, was holding. In the melee, Jack Hart shot a fellow escapee.

Jack Hart carried the smuggled .32 caliber ‘Savage’ gun with the serial number 241728 etched into it. Hart held it with the safety off and a live shell in the chamber ready to fire. Several witnesses, including inmates who escaped, made statements that Hart was the sole possessor of this gun.

Hart claimed during the chaos he gave the gun to Jimmy Collins but later recanted his statement attempting to implicate Williams as the shooter. Sergeant Daff told State Troopers hours after the escape, “He (Hart) was the one with the gun and he didn’t give it to anyone.” Since Williams previously murdered a Beckley Police Officer, Hart thought he could pin this nefarious crime on him so he would not be charged with it.

In inmate David Effingham’s statement to the police, he stated Jimmy Collins was the last one to possess the gun firing the fatal blow, but other inmates claimed that it was either Hart or Layne. Other inmates reported that Harold Gower was the final possessor of the .32 caliber pistol as they claimed that he (Gower) emptied all six shots toward State Trooper Kesner hitting the inside of the car door once and Donald Layne. An undisputable fact is that this gun was the one that caused the fatal wound to State Trooper Philip Kesner.

Contrary to popular belief, Williams was not at any time near State Trooper Kesner’s car or the fatal activity that took place around it. When Burton and Collins first overwhelmed the gun cage and snatched Correctional Officer Villers’s .38 caliber revolver, Collins handed the revolver to Williams and was ordered by Hart to say, “Give this gun to Donald Layne.”

Layne was agitated and angry with Williams as he didn’t give him the gun that Collins gave him but kept it. Williams ran toward the car he previously arranged to be on Jefferson Avenue. In a statement to police, Layne said he saw Williams get into a car, start the engine, and drive north on Jefferson Avenue by himself.

Williams gave specific instructions for his getaway car to be parked on the right side of Jefferson Avenue so that he was closer to the prison’s front door and pointed toward Wheeling. Layne was furious because Williams had a gun he was supposed to have and he left without the other inmates.

Since its closure in 1995, the former prison has been a tourist attraction.

One Fatal Shot

Williams did possess the .38 caliber revolver but didn’t fire it. One of the escaping inmates, Thomas Burton, reported that he was “sure” Williams possessed the .38 caliber gun which was the pistol taken from Correctional Officer Villers. It was easily identifiable because it had been issued to Officer Villers by the penitentiary and “W.V.P.” was clearly marked with deep engraved etchings into the weapon. It was a .38 caliber Smith and Wesson revolver with a four-inch barrel with the serial number, 5K87049.

After multiple shots were fired, Mrs. Kesner saw State Trooper Kesner lying on his back on the street and crawled over to him. His final words to her were, “I’ve been shot in the chest.” John Terek was an emergency responder for the Moundsville Fire Department and was the first on the scene. He offered the trooper medical assistance.

He carefully opened State Trooper Kesner’s shirt and saw a penetrating wound in the upper left side of his chest. At that time, Trooper Kesner was still alive and had a strong pulse and breathing. He was quickly loaded onto a stretcher and rushed to the Reynolds Memorial Hospital in nearby Glendale, West Virginia.

State Trooper Kesner bravely died from one .32 caliber gunshot wound and was pronounced dead at 8:53 p.m. His mortality was brought on by the bullet entering the left side of his chest and passing through the anterior and posterior wall of the left ventricle of his heart. He was loved by many and his brief career ended too soon.

After the mayhem in front of the penitentiary occurred, six inmates got into the car and frantically fled the scene. Jack Hart, Thomas Burton, David Morgan, Harold Gower, Jimmy Collins, and Donald Layne drove south in the car while nine other inmates fled on foot.

Ronald Turney Williams is a sadistic murderer who took the lives of at least two innocent people but was not at the scene of State Trooper Kesner’s death. After absconding from the prison, he ran to the south end of the prison where his Brother-in-law, Bill Hicks placed a getaway car the day before. Hicks smuggled in the keys to the car in a fast-food container during contact visitation on November 6h and all along, Williams knew he was immediately heading there after the escape.

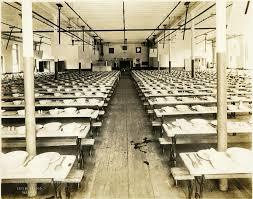

There were not many photographs taken inside the prison.

Read the full article

0 notes

Link

Here is a tattoo by Joe Capone. He was on the TV program "Ink Master." (Photo Provided) The Locked Up Tattoo Convention, Dark Carnival and the Old West Virginia Penitentiary are scheduled for June 16-18 in Moundsville. Convention organizer Shawn Alexander from South Point, Ohio, said he had held exotic animal expos and oddities at the location...

#TattoosNews#FormerPrisonTattooConvention#LockedUpTattooConvention#MoundsvilleTattooEvent#UniqueTattooExperience#WestVirginiaPenitentiary

0 notes