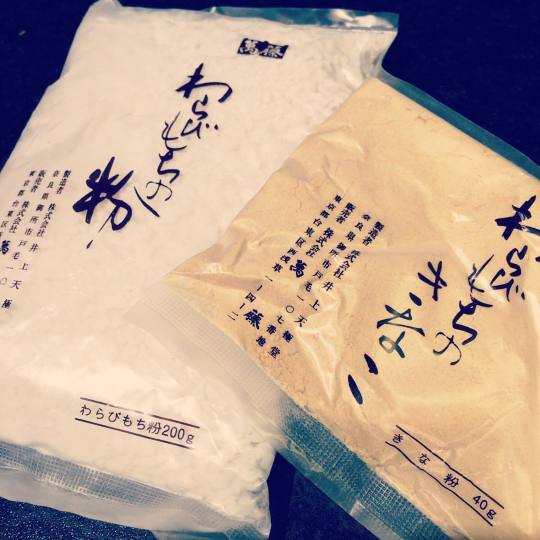

#warabiko

Photo

DIY Warabi Mochi わらび餅

These "Warabi Mochi わらび餅" are soft, chewy, and jiggly. Dusted with nutty roasted soybean powder and drizzled with brown sugar syrup. Made with tapioca starch which is easier to find than warabiko.

✖✖✖✖✖✖✖✖

sew-much-to-do: a visual collection of sewing tutorials/patterns, knitting, diy, crafts, recipes, etc.

#DIY#recipe#dessert#treat#warabi#mochi#chewy#soybean#brown sugar#sugar#sweet#syrup#tapioca#tapioca starch#warabiko#aapi#aapi month#yummy#delicious#food#good eats

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wheat flours (小麦粉/komugiko)

In Japan, white wheat flours are mainly divided into three different categories and differ only in the first character so you can be confident that you are buying wheat flour if you see either of these sets of 力粉 (riki ko) or 力小麦粉 (riki komugi ko).

Bread Flour:強力粉 (kyou riki ko)

Japanese bread flour has a high gluten content with at least 12% protein content. Use this coarse flour for breads, noodles, and dumpling wrappers.

All Purpose flour:中力粉 (haku riki ko)

All purpose flour is likely the least common of the three flour categories in Japan. This flour has around a 9% protein content and moderate gluten viscosity making it suitable for udon noodles and day to day confections.

Cake Flour:薄力粉 (chyuu riki ko)

Cake flour has less than 8.5% protein content and, like its counterparts around the world, has low gluten content. Use this flour for everything from cakes, okonomiyaki (see our recipe here) to tempura!

Whole Wheat Flour: 全粒粉 (zenn ryuu funn)

As in any country, whole-wheat flour weighs more by volume than regular white wheat flours.If you would like to substitute regular flour with whole wheat to get more whole grains/fiber, try substituting half the totalvolume with whole-wheat.

Rice Flours (米粉/komeko)

Rice flours are very common in Japan and you will find many varieties at grocery stores. The most common uses are all for wagashi (Japanese sweets) but the texture of a final product differs depending on the variety of rice flour that is used. Rice flours in Japan are either made of non-glutinous rice (the rice used for dishes such as sushi and oyakodon) and glutinous rice (used for mochi in Japanese cooking and often seen in the US as the main ingredient for mango sticky rice at Thai restaurants).

Fine Rice Flour: 上新粉 (jyoushinko)

Jyoushinko is a fine powder created from polished non-glutinous rice flour. Because it is made of ordinary rice rather than glutinous rice, jyoushinko creates dishes that have a harder texture and are less sticky. The most common uses for jyoshinko are for kashiwa-mochi (red bean rice cake wrapped in oak leaves) and uiro (a sweet rice jelly). Contemporary bakers often also use jyoushinko for baked goods such as cakes.

Sweet Rice Flour: 白玉粉 (shiratamako)

Shiratamako is made up of polished glutinous rice ground into coarse granules. Shiratamako is unique because of its absorbent nature which allows for a smooth and elastic dough. Activate shiratamako by mixing it with cold water and use it to make all types of wagashi (Japanese desserts) such as daifuku and shiratama dumplings.

Glutinous Rice Flour: もち粉 (mochiko)

Mochiko is made of glutinous rice flour and is coarser than shiratamako. Compared to shiratamako, mochiko creates a softer and chewier dumpling. The primary use for mochiko is to add sugar in order to create gyuhi, a primary ingredient for wagashi.

Dango Flour: 団子粉 (dango-ko)

Dangoko is a blend of glutinous and non-glutinous rice. By soaking and drying the two types of rice together and then grinding them, manufacturers are able to create a more chewy texture compared to mochiko and shiratamako. As its name suggests, use this flour to make dango (Japanese dumpling balls).

Other “flours” (粉/kona)

These “flours” are actually often starches and are made from the root of plants native to Japan.

Warabi Starch: わらび粉 (Warabi-ko)

Warabiko is the starch made from the ground roots of the Japanese Warabi plant, also known as bracken. This fiddlehead fern creates a distinctive starch which is mild in sweetness, transparency, and has a jelly-like texture. The most popular use for it is to make warabi-mochi, a jelly-like wagashi (japanese sweet) most often enjoyed with kinako (soybean powder) and kuromitsu (Japanese black syrup).

Kudu Starch: くず粉 (kudu ko)

Kudu starch (also known askuzu) is made fromkudzu, a climbing vine which grows native in Japan. The entire plant is used: the leaves feed livestock, the stems are used for cloth, and the roots are dried and ground to make starch powder. The powder is commonly used as a thickening agent and can be found inwagashi (traditional Japanese sweets) as well as savory dishes.Compared to other starches, kudzu starch does not have a starchy taste and is clear and transparent, making it a superior choice for glosses and in soups, sauces and desserts.

Potato Starch: 片栗粉 (katakuriko)

Katakuriko is the Japanese name for potato starch and is used as a thickener in Japanese cooking. It was originally sourced from dogtooth violet plants but now is sourced from potatoes which are cheaper and more accessible. Make sure not to confuse katakuriko with potato flour as this starch is very fine, has little fiber or protein and has no taste.

Barley Starch: はったい粉 (hattaiko)

Hattaiko is a flour made of roast barley. It is a healthy food that can be used similarly to kinako (soybean powder) and has high fiber and protein contents. Try adding this powder to your sweets or even mixing it into batters for cakes!

0 notes

Text

Indonesian Mochi From My Friend's Family Recipe

Do you know that in the many regions of East and Southeast Asia, people love to eat mochi-like dumplings? While mochi is commonly known as a Japanese delicacy, it actually originates from China, where it is called tang yuan (boiled rice flour dumplings with sweet black sesame filling). In Indonesia, mochi comes in the similar form of the popular mochi ice cream in United States: colorful and the skin is pre-cooked, not boiled like tang yuan. It's called moci, which has peanut and sugar filling. The texture contrast of ground peanuts and chewy skin leaves you wanting to chew more. Mochi and other mochi-like delicacies are eaten at different occasions, but they can be eaten any time of the day, year-round. In Japan, mochi is a traditional item eaten during the new year as a symbol of good luck. In China, tang yuan symbolizes reunion. In my country, moci is eaten as snack.

Most mochi is made with glutinous rice flour, however, variations among families exist. The variations are usually made to cater different preference of chewiness, by adding other types of starches (corn, rice, tapioca, warabiko, and many more).

I was on a weekly catch up session with a middle school friend of mine, Yasmine Hudiono, talking about what we ate that week and what we want to make the next week. Over the past three years, Yasmine and I grew to bond over our interest in cooking. She was telling me that her new job as a corn byproduct sales specialist introduced her to this knowledge that there is actually contrasting difference between many types of starch. That is when she said, "do you know that my family usually makes moci with tapioca instead of glutinous rice?" I asked her, "how is tapioca different from glutinous rice?"

The moci is made in the same manner like making it the usual way. However, by swapping the glutinous rice flour with tapioca, it results in major texture difference. If glutinous rice flour results in tender, a bit sticky, and chewy skin... Tapioca results in bouncy, stretchy, and non-sticky skin that retains itself more. If you think it is similar to boba pearls, it is not. I absolutely love the different experience of chewing the tapioca-based skin. As you bury your teeth into the skin, they don't instantly tear, but they kind of get squished as if they were about to burst. As I am trying to describe the texture, somehow I got reminded of this scene from The Incredibles when the dad got shot by multiple amount of boba-lookalike sticky balls.

The only challenge here is the difficulty in handling the dough. Since tapioca tends to retain itself more, it is little bit hard to stretch compared to glutinous rice flour. But I think the result is worth the effort!

Ingredients:

1 cup tapioca flour, for skin

1 cup water

1/8 teaspoon of neutral oil

1/2 cup peanuts or cashew nuts (I mixed both), roasted and unsalted

1/4 cup brown or white sugar (I used brown for the caramel flavor)

1/4 tapioca flour, for dusting

Instructions:

Dry roast nuts on hot pan until you can hear it sizzle. If using raw nuts, put in in 350 F oven, stirring occasionally until the natural oil is released

Pulse nuts and sugar in food processor until they become a bit like dry, crumbly paste. The natural oil of the nuts will make them come together in chunks

Dry roast 1/4 tapioca flour on lowest heat possible until the flour is very powdery, even more powdery compared to when they come from the package

Stir 1 cup tapioca flour, water and oil in a nonstick cold pan until a slurry is formed

Turn on heat on medium, stirring the mixture with a strong spatula. When they start to curdle, turn the heat to lowest setting and continue stirring until a dough form

Continue turning the dough around until it becomes translucent, looking like a chicken breast. Remove and to a plate dusted with the heated flour and dust with flour on top. Let cool to warm temperature

Divide the skin dough into small portions

Take a portion of dough and stretch with your fingers. Maintain the shape by sticking it to your fingers and scoop fillings. Close the dough with pleating motion, moving slowly to ensure that the dough will not rip

Dust the dough to prevent sticking

Tips:

The dough is sticky, but it is mostly sticky to itself

It is important to not panic when it sticks to your finger. Just lift your finger slowly and the dough should pull itself from your finger

If tapioca sounds too intimidating, feel free to swap 1/4 of the tapioca flour with rice flour. Rice flour, different from glutinous rice flour, does not have sticky and glutinous characteristics, similar to cornstarch

1 note

·

View note