#romance fiction etc has a lot of merit and so it makes sense that an F/F fandom ghost wouldn't have the same traits because a lot of female

Text

so, I read the full fanlore page for that whole ‘fandom ghost’ thing about m/m and the way there’s this one character that keeps being written into every character over and over, across pairings, inserted into a usually minor or underdeveloped character, etc

and there was a section on a female ghost that also tends to show up in a lot of these m/m fics, a smart, sassy, beautiful female character who is also reduced to being an enabler for the m/m ship, etc.

And while I don’t really read m/m, that does track with my limited exposure.

BUT, I think there is also a fandom ghost in f/f fic too. I honestly don’t read the wider f/f widely enough to articulate it as much, just what’s in my fandoms and I don’t really have an expansive set of them or add new ones that easily.

BUT in my experience, and from what I see in summaries and tags on ao3 and posts here on tumblr, there is a common character archtype wedged into characters regardless of if they fit, across a lot of femmeslash stories.

I can’t give a solid point by point as I write this at 5 in the morning, coming off stewing over the thoughts in my sleep, or so it feels, but like:

the m/m fandom ghost is a type a personality, controlled and tsundere and hypercompetent and gets wrecked by the messy guy that comes in and destroys their carefully crafted life, etc.

The f/f fandom ghost that I’ve seen is actually the opposite. That is, when given two characters that seem like a viable ship, one of the characters is whacked with a hammer until she fits a mold: an often clumsy or perhaps more accurately careless, butch (and made more so than her canon presentation), very muscular (again, more so than her canon presentation), often quite a ladies woman, very toppy, definitely plays opposite a more repressed or controlled character (but usually one who is bettered rooted in canon as being that), and destroys that character’s neat little world. They are usually, despite their butchness, a lot sillier or softer outside the bedroom, again, and they think sunshine comes out of the other character’s ass even before they get together and -

I’m starting to run into some limitations on the specific words because I just don’t read this enough to stop and articulate it (because I often close out of F/F fics that get too into wedging the characters into archetypes like this rather than the characters themselves (because it does happen a lot) but I very much do have a ‘I know it when I see it’ thing happening here.

I’ve seen it crop up in Buffy/Faith, Kara/Lena, Regina/Emma and in others I have read less extensively (there are F/F ships I’ve never seen it in, like Tara/Willow) that I’m not thinking of specifically

And like, there is a bit of a difference between the m/m fandom ghost, which is really the same character being dressed in a new skin over and over, and that skin usually being a minor or secondary character, etc, and this f/f one, which is more likely (but not always) to be fit into a fairly prominent character, and is less like one character wearing different skin and more many square characters being badly bashed into one round hole, but

I feel like I’m on to something here. For some femmeslash writers, there really are a lot of fics that feel like they’re not writing the two characters. They’re writing the one character and an archetype that may not actually fit the other character all that well, but damn the Torpedos and full speed ahead.

#Musings#Just Little Fandom Things#Just Little Shipping Things#Femmeslash#The Fandom Ghost#I think the argument in those comments put on the fanlore page about the ghost hux/etc having a lot of classically female traits from#romance fiction etc has a lot of merit and so it makes sense that an F/F fandom ghost wouldn't have the same traits because a lot of female#characters already have them#and instead the f/f fandom ghost essentially inverts the dynamic#rather than inserting a controlled tsundere hypercompetent character to be wrecked by an existing hot messy one#they invite a hot messy one to wreck an existing controlled hypercompetent and often tsundere#Like I've seen this in many ships even if specifics escape me but the specific one where this bashing into a round hole thing#comes to mind for me right now is the way Kara in supercorp fics is all too likely to be butchified#like Kara in the show is *not* butch but my god do some fanfics just bash her into that shape or otherwise try to make her fit an#oft-used dynamic#Kylia Writes a Novel In The Tags#Kylia Has a Thought She Can't Get Out Of Her Head But Also Has Trouble Articulating It As Clearly As She'd Like#Thinky Thoughts Thinking Through The Thick

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do a lot of book reviews, and so I am occasionally asked how I handle the discomfort of trying to be "objective" when evaluating art. The truth is, I don't; I aim for empathy: the understanding that someone can do something I don't like and don't get and it can be good; and self-confidence: assurance that I make my judgments lovingly and with sufficient thought.

With that said, here are my Grand Thrix ways of judging good art (my own and others'). Maybe they will help some other people! (Even if only to decide that they don't trust my taste. ^^)

1. WHAT IS THE GOAL?

2. IS IT A GOOD ONE?

3. DID THE ARTIST SUCCEED?

focus factors: intention, good-heartedness, and surprise.

WHAT IS THE GOAL?

It's useful to ask what an author appears to be trying to do-- does this author value lengthy description, for example, or are they trying to be as concise as possible? Do they want to surprise the reader with a plot element, or is this a case of intentional dramatic irony? Does the author want their work to move slowly or quickly? How do you know this, and how certainly do you know it?

Above all else I want to read a confident book: a book where the author could not only defend every choice, but speak passionately on why they chose it. Is the prose concise or long-winded? Does the plot meander or adhere to strict regularity? How does the book maintain conversation with its fellows? "Effort," "difficulty," or "originality" are smokescreens: any choice can be justified, and I want to see the author choosing with intention.

Examples: Most Romance genre books are purposefully using simple prose. A book's climax is almost certainly trying to be climactic. It can sometimes be hard to tell whether an author is intentionally or accidentally confusing the reader.

IS IT A GOOD ONE?

What makes a good artistic endeavor, to you? I generally prioritize good-heartedness (love, joy, kindness, etc.-- which can manifest in making your reader sob like a baby!) and surprise (doing something new with something old, showing me something unique, working around my expectations) above all else. You might prefer goals of genre-busting, progressive politics, pushing the boundaries of language, and so on. Frankly, there's no objective answer to whether you "should" or "should not" try to do a given thing with your art.

Examples: Most literary fiction is not concerned with the kind of plot structure I personally love. Books written with other minority groups in mind may purposefully alienate me in order to make a point about whose perspective ought to be catered to. Some books intentionally insult the reader in a way I don't feel is merited.

DID THE ARTIST SUCCEED?

We all know the feeling: the book is supposed to be sexy, and it is not. The scene is supposed to be serious, and it is not. The dialogue is supposed to be funny, and you wish you were being shot in the head rather than forced to read it. I try to ask myself how confident I am in what the author wanted and why they might have failed before railing against a book; there's a difference between a debut author struggling with plot and an established author being transphobic because nobody bothered to hire a sensitivity reader.

On the other side of the coin, you have the books that don't personally connect with you but are clearly well-written: filled with tropes you don't like, effective at elements that annoy you, ultimately not something you enjoy at all but clearly effortful and lovingly crafted pieces of art. Often I have to concede the author is doing something fascinating and doing it well, but good Lord if it doesn't personally bore me to tears. Oh well! Someone out there is reading the same book and gushing; it's just a matter of getting the right reader.

Examples: I was confused, but I see that the author wanted to confuse me, and though I didn't enjoy that confusion, I agree that it made sense and it worked; credit is due. When I'm reading YA I often give allowances for a novel which has a lot of silly unbelievable drama, because it's more than fair to write that way for teens. You won't find me knocking bara just because that's not my kind of man; clearly it works for its audience (whom I love).

To put it more broadly, did the artist go into their work hoping to do something (with intention)? Was the thing they were hoping to do something worth doing (something good-hearted and interesting)? Did they succeed? If so: 5/5! I hope this metric is useful to someone else, and that it brings infinitely more artistic joy into the world.

#txt#booklr#writeblr#bookblr#yves talks#on reading#important writing updates#This is really just a reference like I said. I'm curious what other people's lists would look like.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some musings on the genre/literary fiction distinction

(Aka: wow! categorization‚ huh!)

To me‚ and to (as far as I’ve seen) the contemporary literary fiction community‚ the literary/genre divide is not a matter of distinguishing between quality or merit‚ but rather styles of narrative. Both are crucial to the world wide tangled web that is storytelling.

Genre fiction‚ to me‚ has a beautiful goal; the modus operandi is ‘expand imagination.’ Make something up‚ then take it as far as it can go. Slice it up and make new things out of it‚ and keep going‚ and keep going. It’s about tunneling deep into the heart of your creations‚ and of the collective creations of those who came before you. Whether we’re talking sff, romance, horror, etc. It’s full to the brim with soul—human soul. We need this.

Literary fiction‚ on the other hand‚ wields stories like tools‚ much like how a metaphor is a tool for understanding. So literary fiction is metaphors within metaphors. The story is a metaphor for something else, and everything in the story is a metaphor for the story. It’s a matryoshka doll of metaphors. Unlike genre fiction‚ nothing here exists just to exist: it needs to justify itself in the narrative. This is just as necessary. We need these stories to make sense of our world.

To summarize‚ genre fiction is about stories-as-stories‚ literary fiction is about stories-as-something-else. Story servicing the story elements vs story elements servicing the story.

(Now is where‚ if you’re like me‚ you question whether every story can be sorted that way. Of course not. Here on werecat dot edu, we live for that grey area in between.)

Other distinctions:

Yes‚ literary fiction tends to pay more attention to prose and intricacies of language, because those stand out more in the absence of vivid plotting and characterizing. Genre fiction is by no means incapable of beautiful‚ intricate writing (N.K. Jemisin! Marlon James!).

Literary fiction incorporates “genre” elements! Very often. I’d say much more so these days. in fact‚ “literary fiction with sff elements” is a favorite category of mine. You are allowed to put werewolves‚ vampires‚ AIs‚ complicated fantasy creatures‚ ANYTHING into your literary fiction. (Please read Karen Russell’s short stories‚ she’s very good at it.) It can be trippy and bizarre and fantastic.

Additional thoughts:

The “literary fiction is character-centric‚ genre fiction is plot-centric” argument rankles me. A lot of literary fiction isn’t concerned with having compelling characters‚ they’re just there to be focalizers‚ so we can see through their eyes what the story is doing to them. And many works of genre fiction rely heavily on their characters and less so on the plot.

I don’t think “literary fiction” is limited to literature at all. Maybe a radical idea. Movies can be literary. Tv shows can be literary. Comics can be literary. Video games can be literary. Web fiction? You guessed it, Can be literary.

Though I hope this is now obvious‚ no one has the moral or intellectual high ground re: their fiction preferences. Here is a fun‚ sort of out-there example for you. I watched puella magi madoka magica recently. I liked it‚ but it frustrated me. See‚ it was sold to me as “a darker magical girl story.” Perfect! Love the concept. The issue? It wasn’t that. I mean‚ sure. There were magical girls. It sure was dark. But it wasn’t a dark magical girl story‚ because it wasn’t a magical girl story at all. I expected it to explore what a magical girl is‚ but it wasn’t built to do that. It was telling a different kind of story‚ one about the trials and tribulations, the grief and strife of girlhood. Magical girls were the conduit for that story, is all. And that’s the kind of thing I’d usually love! How intriguing! But expectations are important, and I didn’t appreciate being misled like that. I imagine my rewatch will be much better.

And that is why I think the distinction still has usefulness for marketing. If Karen Russell sold her fantastical stories as sff‚ sff readers would be (justifiably) pissed, even though the stories do have werewolves and vampires and things like that in them. Categorization is messy‚ and so incredibly fallible‚ but it’s very human of us to categorize.

#long post#~#tried to do the thing where you bold sentences as an anchor for the eyes#let me know how/if it works!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

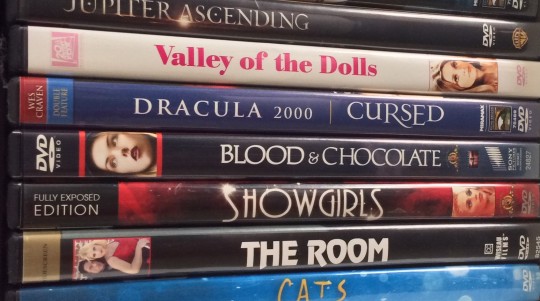

Blood and Chocolate: An Adaptation in Name Only

Previously: Section 0 – Introduction, Section 1 – The Book, Section 2 – Adaptation Challenges

Section 3 – The Adaptation

Preface: The 2007 adaptation of Blood and Chocolate directed by Katja von Garnier and written by Ehren Kruger and Christopher Landon did not receive critical acclaim. It stands at 11% on Rotten Tomatoes, and a New York Times review by Jeannette Catsoulis called it “uninvolving and cliché-ridden”. The box office returns were similarly underwhelming, grossing $3.5 million domestically and $6.3 million internationally against a $15 million budget – an $8.7 million loss for a production company used to receiving at least a modest return on investment for other, similar properties.

(Ahem.)

But, does it have any merit?

It may have failed by the metrics of profitability and critical response, but that does not mean that the film was an entirely, or even partially, failed endeavor.

Summary: Following a surprisingly faithful Romeo and Juliet plot, the movie Blood and Chocolate centers on Vivian, the werewolf Juliet, an orphan living in Bucharest with her Aunt Astrid, who serves as a rough Nurse analogue. They are ruled by Gabriel, the Paris, a tyrannical pack leader with romantic designs on Vivian. The human Romeo, Aiden, is a wandering American artist who encounters Vivian anonymously in an empty church, whereupon he becomes determined to find and court her.

Meanwhile, tensions are rising with the Tybalt character, Vivian’s cousin Rafe. He discovers Vivian and Aiden’s romance, threatens Aiden, and is eventually killed by Aiden in self-defense.

Eventually, Vivian gets poisoned and she and Aiden attempt to escape the city. She is captured and locked up in Gabriel’s headquarters, where Aiden arrives and rescues her. In the process, Vivian kills Gabriel. Afterward, they escape, steal Gabriel’s car, and drive off into the sunset.

Also, there’s a prophecy about Vivian? More on that later.

Themes: The themes of the movie deviate sharply from the themes of the book. No longer does Vivian struggle with what she wants as opposed to what she needs, because the movie removes any such opposition.

In the movie, as in the book, Vivian wants to be with Aiden, but the movie rearranges the rest of the plot and the characters so that what she no longer needs to accept (and find a partner who also accepts) her dual nature as a werewolf to find happiness and fulfillment.

Instead, what the film version of Vivian needs is to get away from her creepy, possessive pack leader and forge her own destiny. This “need” no longer stands in opposition to her “want”. On the contrary, the two share a resolution – run away from Bucharest with Aiden.

The tension between the human and the animal sides of Vivian’s nature is also reworked. In the book, she can’t pretend to be human, but she also can’t lose control and give in to her animal side. She needs to balance both.

The movie, on the other hand, has Vivian definitively choose her human side by choosing Aiden. Actually, no, it’s not just that she chooses her human side – the movie shows her actively rejecting her werewolf side throughout the movie. And, well, given the way that werewolf society is treating her, I can’t really blame her. I wouldn’t fight to stay with these people either. They were ready to pair her off with a man old enough to be her father without her consent.

Honestly, I wasn’t really wondering why she wanted to leave with Aiden, but more wondering why she hadn’t left already.

This leads into the theme that was added for the movie: destiny vs. choice. As a girl from “the line of Kings,” Vivian is destined by a nebulous prophecy to lead the Bucharest pack into the Age of Hope. Who prophesied this? If she’s from the line of Kings, why is Gabriel leading the pack? Does Vivian even fulfill this prophecy? We never really find out.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a sucker for a prophecy storyline. It just – it has to matter. And the prophecy in this movie does not matter. You could cut every mention of it, and nothing substantial would change. One of the biggest mysteries about this movie is why the screenwriters added a prophecy element if they weren’t going to bother to pay it off.

She is also destined (either by the prophecy or because Gabriel says so) to be Gabriel’s next mate, continuing the tradition of the pack leader choosing a new mate every 7 years. Vivian does not appear to have a choice in the matter.

Throughout the movie, Vivian feels chained by this destiny, leading her to keep Aiden at a distance and warning him away from her. Aiden, however, ignores her boundaries and her clear wish to be left alone. He tells her that she needs to ignore her family’s plans for her and make her own choices, mostly because he’s hoping that she’ll chose to date him.

In the end, Vivian accepts Aiden’s outlook, choosing to defy Gabriel’s wishes by saving Aiden and escaping Bucharest with him.

Highs: There are two major elements that I like about this movie, and I do honestly like them. I’ve watched this movie a lot, and, no, it’s not just hatewatching. I genuinely enjoy this movie.

o The Cast: I really like Agnes Bruckner. She was great in the slasher movie, Venom, and I think she made an admirable Vivian. Despite some of the cheesier lines, she turns in a decent performance. I believed that she felt guilty about her family’s deaths. I believed that she felt torn between her attraction to Aiden and her duty to her pack. I even believed that moment in the ending where Vivian can’t bring herself to kill Gabriel, despite the threat that he represents.

Of course, the script ruins that seconds later when she just… shoots him anyway? Also, and this is a violently American thing to say, but did they have to use the wimpiest sounding gun possible?

I think that Hugh Dancy as Aiden was the standout performance of the movie. He portrayed Aiden as playful, sweet, and resourceful, and his switch from sensitive artist to unlikely badass is nicely set up with his story about defending himself against his abusive father. I also think that he and Bruckner have some decent chemistry. Say what you will about the romantic fountain montage - they look like they’re genuinely enjoying each other’s company.

Also, he spends the last half of the movie bruised and slightly bloody, and I don’t mind that at all.

As for the rest of the cast, I think they gave fine performances despite the material that they had to work with. When movies fail, there seems to be an impulse to blame the cast and rip their performances apart – but I won’t. I don’t blame the cast for the commercial and critical failure of this movie – I blame the people who had actual creative control (the producers, director, screenwriters, etc.).

o The Concept: An ancient dynasty of werewolf leaders extending from primeval Europe into the modern day? Yes fuckin’ please! This is exactly the kind of canon expansion that I was craving from the book!

And, okay, yeah. The book’s version of werewolf society is very different from the movie’s version. In the book, werewolf packs are moderately sized clusters of families and individuals ruled by an alpha pair. Other werewolf packs exist, but there doesn’t seem to be any person or group governing werewolf society as a whole.

This would seem to directly contradict the movie’s take on werewolf society, but it doesn’t have to. The book’s werewolves originated in western Europe, and from there emigrated to the US in the 1600’s. The movie’s werewolves originated in eastern Europe and stayed there. There’s no reason why those two groups of werewolves couldn’t have started with or evolved two different social structures leading up to the present day.

In fact, if you can ignore the shared titles and character names, the movie Blood and Chocolate can be viewed as a new story set in the fictional universe established by the book Blood and Chocolate. And that’s how I choose to view this– it lets me get past my nerd rage and enjoy the movie for what it is.

Lows: While I do honestly enjoy this movie, I would be lying if pretended that it was flawless. Blood and Chocolate didn’t get its reputation by accident. Here are my thoughts on some of the more egregious missteps.

o The Script: Okay guys, we need to talk. I’ve seen people defending this movie, saying that it’s an unfairly maligned gem, and I CAN’T. Guys, the dialogue. Have you LISTENED to the dialogue?

Aiden, pleading: “I’ll take the train, I swear it. I’m gone. I’m on that train.”

Rafe: “I AM THE TRAIN!”

(Boy, WHY are you crouching on the railing like a heterochromatic gremlin?)

Like I said in the last section, I don’t blame the actors for the movie’s failure. I don’t. They had no control over this shit. I do, however, blame the screenwriters; all SIX of them. This film had SIX separate people working on the script and was still released with Hugh Dancy shouting, “If you cared a goddamn thing about me, you would have left me before we ever met!”

This is astonishing for its misunderstanding of linear time if for nothing else.

Seriously, though – Hugh Dancy, cinnamon roll and internet darling, cannot make these lines sound good. When even the best actor in your movie can’t make it work, you know that the script is baaaaad.

o The Wolves: Remember the bit about practical effects vs. CGI in the previous post? Yeah, the filmmakers went hard on the CGI. It made sense given the relatively small budget to go the CGI route as a money saving maneuver. However, the director, Katja von Garnier, decided to use the CGI in the most ridiculous way possible.

(🎶 FIGHTING EVIL BY MOONLIGHT! 🎶)

The werewolves jump into the air, turn into an ethereal glow, and emerge as wolves. While this is not an inherently bad idea (it’s different, and it could, in theory, look cool), the execution was a huge misfire. Seeing the actors leap forward into a sparkly, pastel shimmer was never anything but ridiculous, and the Sailor Moon aesthetic of it just did not fit with the grungy, realistic look of the rest of the movie.

(Hey, cinematographer: if you want these transformations to fit with the rest of the movie, maybe make the movie LESS F*ING BROWN?)

Additionally, the transformed werewolves were simply real wolves. Listening to Katja von Garnier’s commentary, you come away with the impression that she is suuuuuper proud of getting the cast and crew to work with live animals. However, the wolves that they used are a bit on the smaller side.

As a result, they didn’t really inspire much fear. For example; in the scene where Rafe murders the girl he’s been stalking, you see both the girl and the wolf in the same shot, and it absolutely kills the tension. Like, girl - roll up a newspaper and boop him on the nose.

o Rafe: The screenwriters desperately wanted Rafe to be menacing, and bless Bryan Dick for trying, but it does not work at all. Rafe in the movie is petulant, sleazy, definitely an asshole, and explicitly a murderer, but I never believed him as a threat.

In the confrontation at the chapel, Hugh Dancy stands half a head taller than Bryan Dick, and while neither of them are exactly musclebound, it’s pretty obvious who would win in a fight. For me to buy Rafe as a legitimate danger, he needed to be less foppish, more unhinged, and just physically bigger.

(FFS, Vivian is taller than he is! How is he supposed to be intimidating?)

o Gabriel: I don’t know who decided to turn the romantic lead of the book into the jealous villain of the movie, but they need to be slapped across the face with a trout. It’s been over a decade since the movie came out, and I have learned to shrug off most of the bizarre adaptational choices, but this one still just pisses me off. The evisceration of Gabriel’s character is the biggest betrayal of the source material.

In the book, Gabriel was a foil to Aiden, and Vivian choosing Gabriel symbolized her acceptance of her dual nature. It meant that she wouldn’t have to compromise her identity to be accepted and loved.

The adaptation could have provided an opportunity to rework Gabriel’s character arc. It could have cleaned up the age-gap ickiness, removed the non-consensual kiss, nixed the prior relationship with Vivian’s mother and generally made Gabriel as a love interest more palatable for movie audiences.

But, whatever. The filmmakers already threw out the core of the human vs. animal theme from the book, so why not just utterly warp Gabriel while they’re at it? Plus, the clueless human love interest vs. the lecherous supernatural stalker dynamic worked for Underworld, so it’s going to work here, right?

The Stuff I’m Choosing Not to Nitpick (in depth): I just- I don’t know, man. I used to get really worked up about this stuff, but I don’t really feel like devoting any real analysis to these points. Take these potshots and do with them what you will.

o The Parkour: Time has not been kind to parkour. The filmmakers gambled on it being cool for the long haul, and they lost that wager. I get that it takes a lot of skill, and I get what the filmmakers were trying to do with it, but it just looks silly.

o The Hunt: I mean, it directly violates the most important werewolf law from the source material, but I’m willing to believe that this ancient werewolf faction in Romania came up with a sanctioned way to hunt humans, so I can forgive this.

o The Eye Thing: The early-mid aughts were really impressed with the power and symbolism of colored contacts, weren’t they?

o Astrid: They mashed Astrid and Esme’s characters together and called the resulting chimera Vivian’s aunt. I don’t hate this change as much as I used to. I mostly just wonder why they bothered. The movie had already changed the book’s storyline so much that neither Astrid nor Esme were necessary for the new plot. They could have cut this character out entirely and no one would have missed her.

o The White Wolf: Of course the main character turns into the only white wolf in the movie. ‘Cuz symbolism!

o The (implied) Sex Scene: Sure, she’s dying of silver poisoning, you’re both hiding in a decrepit film warehouse and the werewolf mafia is hunting you, but GO AHEAD. This is the ideal time AND place to bone!

(This woman is clearly DTF.)

Verdict: I want to be really clear on this point – I love this movie. I mean, let me remind you of my cinematic tastes.

Here’s the thing - there is a difference between movies that are “good” and movies that are “enjoyable”.

Blood and Chocolate is not a “good” movie. The plot is formulaic as hell, the dialogue is laughably inept, and any actual potential it had to do something new and innovative with the werewolf genre was squandered. Seriously – one of the remarkable things about the book was how it centered a monster story on the monsters and made them sympathetic. The movie? Turns the monsters back into one-dimensional bad guys. But, hey, at least they made the transformations maaaaaaagical!

That said, Blood and Chocolate is absolutely an “enjoyable” movie. I have watched this thing dozens of times since it came out, and each time I find something new to amuse me. The dialogue is hilarious, the special effects miss the mark so badly, and every time you find a new plot hole, an angel gets its wings. What’s more, it contains enough genuinely good elements to balance out the bad. It is a delightful example of low camp, and a worthy addition to any “so bad it’s good” film collection.

I’m not alone in that assessment, either. If you look at amateur reviews of the movie, you’ll find a lot of people defending it despite its flaws. It has an audience!

So, why didn’t it make more money?

Next Week: Section 4 – The Autopsy

#blood and chocolate#annette curtis klause#werewolves#katja von garnier#agnes bruckner#hugh dancy#olivier martinez#B&C-AAINO

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Fiction: An Illustrative Conversation

Author JD Cowan examines Science Fiction: An Illustrated History, by Sam J. Lundwall in the first of many parts. Written in 1975, during the tumultuous years just after John Campbell’s death, Lundwall’s account offers an examination of science fiction history unclouded by the revisionism that accompanied the latest editorial handover in the mid-2000s. Lundwall, a Swedish member of SFWA and other SF organizations, set out to “prove that science fiction is a worldwide phenomenon that hadn’t blossomed in English speaking countries until post-World War I.”

While a European perspective is welcome, as it counteracts American science fiction’s continued provincial myopia concerning World science fiction, Lundwall does a disservice to Poe, Wells, and Burroughs in his claim. Furthermore, English language science fiction was thrust in the limelight after World War I because France, Germany, and other nations involved in both science fiction and World War I lost the spark of hope for the future needed to write science fiction and abandoned the field. American and English science fictions were the loudest voices in a much-diminished choir.

Lundwall and Cowan’s conversation on science fiction sparks many points of discussion, such as the earliest works in the form, how science fiction’s secularization killed its spirit of wonder, and more. Lundwall offers science fiction as the mythology of progress, while Cowan is quick to point out where the mythology diminishes itself:

Mr. Lundwell continues to pry a genre definition from half-formed ideas and made-up terms in order to put to paper what science fiction is. The fact is that it doesn’t have one, and that might be because it is not much in the way of a standalone genre.

Unlike, say, mystery which is about mystery, or romance which is about romance, or adventure which is about adventure, if your genre requires mental gymnastics to explain to a child then you should go back to the drawing board. One sentence should be enough. Genres aren’t aesthetics or themes. Genres are defined by what emotion and sense they are meant to invoke in the reader. This is why the average reader picks up a book. They choose one based on the experience it will give them.

What they are fumbling around to define in the above definitions is Wonder. Wonder is a trait from adventure fiction and its subgenres fantasy and horror. It is the adventure of exploring new lands, peoples, and possibilities. Pair that with the origins of those listed in the paragraph above and you will see where I am going with this, and why the battle for an original definition has been fruitless for well over a century. It’s never going to have one, and that is a point that should be discussed more than it is.

That science fiction might be closer to chinoiserie than mystery or horror is a point to ponder. But it is the following exchange which highlight Lundwall’s claim of science fiction as a global phenomenon–and gores a sacred cow of science fiction in the 2010s:

And to quash another canard, the author continues:

“When some critics argue that the English author Mary Shelley invented modern science fiction with the novel Frankenstein (1818), they forget that she was drawing upon more than fifty years of Marchen literature, most of it infinitely better and more modern than Frankenstein was.”

No, that wasn’t written by Jeffro Johnson. In fact you will soon see that the author is no friend of the pulps or the old stories at all. There is a larger point here. This is a man who stood at fandom’s heart, and here he is admitting what no one currently in that position will. If you accept Mary Shelley as science fiction (and horror, when it’s convenient to the argument) you have to accept many other works that came before hers. You do not get to pick and choose.

You have to accept fantasy and horror as a whole connect to science fiction, and she did not create either of those. She merely continued on in a tradition that started long before she was born and continued long after she was dead. Despite fandom’s best efforts to rewrite the past, she did not create the genre. She was a participant in a unending conversation called art and had her piece. This should be enough.

Those using Shelley as a bludgeon for political reasons are doing her work and those who came before a disservice and are actively whitewashing history–a history, I might add that was crystal clear from all the way back in 1977. Even fandom understood this.

Let’s turn again to Lundwall for an explanation of Marchen literature:

“Modern science fiction in a sense appeared with the German romanticists of the late eighteenth century–Clemens Brentano, Achim von Armin, Adalbert von Chamisso, E. T. A. Hoffman and others. These romantic Marchen writers wrote what in effect were fairy tales for adults, including all the various paraphernalia common in modern sf, such as robots, monsters, strange machines etc, set against a curious background. They demanded an almost boundless credulity from their readers, for they described life, not as a reality, but as a dream of sorts–not what it is, but as it might be.”

We see once again the influence of Romantic literature, with this branch in fairy tales, joining English Gothic tales and Poe’s mysteries as the venerable roots of science fiction. Cowan and Lundwall will disagree yet again over the merits of the Gothic tale, this time, over the appeal of materialism:

But here is where we get the writer’s real opinion of adventure fiction. What follows is his description of The Castle of Otranto, the single most important and popular Gothic novel.

“It had form and no substance, it horrors all lay on the surface as it were . . . the seminal The Castle of Otranto succeeded only in building up baroque facades without much content. In many ways this was the forerunner to the Penny Dreadfuls and the pulp magazines–lots of form, no content.”

I will translate this from arrogant fandomese for the paupers in the audience. “Form and no substance” means the horrors are spiritual, implied, and obvious to those reading, and not explicit.

Cowan describes further the importance of the Gothic:

The Gothic is the beating bloody heart in any good traditional romance story and is what gives it the universal core so needed in fiction. White against black. Dark against Light. Hero against Villain. Eternal Life against Endless Death. Temptation against Virtue. It goes beyond the surface into weighty themes of the Ultimate, God, and True Justice. The knowledge of a battle between forces beyond both parties at play that haunt the scenery and the overall world behind the story. It underpins every action and decision, and the thought that salvation or damnation is a stone throw away is the most nail-biting experience of them all. Now those are stakes, and they were an integral part of all fiction until the second half of the 20th century where the worst thing that can happen to you is that a monster might kill you in the dark where you can’t see it.

Really makes you think.

Indeed, it does, with this discussion of the first chapters leaving readers much to ponder over. I look forward to the rest of this series, and the continued conversation between 1970s’ science fiction orthodoxy and 2010s’ independent rebels.

Science Fiction: An Illustrative Conversation published first on https://medium.com/@ReloadedPCGames

0 notes