#reduce it to a 'religious conflict' between Catholics and Protestants

Text

I'm going to start using a taser on people for their bad, simplistic takes on the Troubles and the IRA

#it's one of those things in which like 80% of people clearly don't know what they're talking about#but insist on having strong opinions anyway#this goes for both sides tbh#and the number of times I've seen well-meaning people#reduce it to a 'religious conflict' between Catholics and Protestants#is wild#and today I just saw someone claim 'the Irish invented modern terrorism' because other terrorist groups copy the IRA'#the IRA car bombs and 'mass shootings'#when the IRA... didn't do mass shootings?#that literally wasn't even their method#and I don't think I've ever seen an English person with an actual good grasp of the Troubles#even the majority of people on the Republic don't have a good grasp of the Troubles#which is something a LOT of people in NI have expressed as a frustration#and I hardly pretend to be an expert#and I obviously didn't experience it firsthand#but I try to be aware of my knowledge limitations

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religion, gender, and the Virgin Mary: Catholics and Protestants

“Prior to the Henrician Schism, Marian devotion was an integral part of English Roman Catholicism. The Rosary was a popular devotion, Marian shrines and festivals abounded, and Elizabeth of York, the wife of Henry VII, followed the practice of well-born women to wear a girdle, supposedly the Virgin Mary’s, during pregnancy. While the sixteenth-century reformers sought to reduce the attention paid to Jesus’ mother, they were not hostile to her, especially in comparison to their Victorian successors. They praised her as a model of faith; they wanted merely to lower her status, not denounce her.

Their condemnation of Marian shrines and relics differed more in degree than in kind from the critiques of their Roman Catholic contemporaries like Desiderius Erasmus and Thomas More. As England slowly became a (predominantly) Protestant nation during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), Marian imagery was appropriated to describe the Queen. Scholars disagree about the extent to which the Virgin Mary continued to be invoked or whether Marian icongraphy was subsumed by descriptions of Elizabeth I.

However, their agreement that the imagery of the Virgin Mary continued to be used in a positive way suggests a continuation of the pre-Reformation tradition, even if the object of that idealisation may have changed. At the same time, an Anglican tradition of restrained Marian devotion began to develop, beginning with Lancelot Andrewes in Elizabethan England and continuing in the seventeenth century by Andrewes as well as other Caroline divines, including William Laud’s protégé Jeremy Taylor, Mark Frank and Herbert Thorndike, and the devotional writer Anthony Stafford, whose The femall glory was republished in 1869 by Orby Shipley, an Anglo-Catholic clergyman (and eventually a convert to Roman Catholicism).

At the parish level, after the Restoration Anglican clergymen held up the Virgin Mary as an examplar of adherence to church teachings. This tradition of a restrained Marian devotion was apparent in the poetry of Thomas Ken, Bishop of Bath and Wells and a nonjuror after 1689. Ken praised Mary as ‘The true Idea of all Woman-kind’ and described her as ‘Mary ever bless’d, whom God decreed,/ Shou’d all in Glory, as in Grace, exceed’. This positive tradition coexisted with one that used the Virgin Mary as shorthand for unorthodox beliefs and practices.

Although the complaints could seem trivial – among the charges filed against Archbishop William Laud at his trial in 1644 was that, while he was chancellor of Oxford University, a statue of the Virgin Mary had been erected over the porch of the University Church of St Mary the Virgin – the fact was that even the apparent trivialities showed how widespread was the assumption that invocations of the Virgin Mary were sufficient evidence of deviation from Anglican orthodoxy. Anti-Marian rhetoric was one component of the anti-Roman Catholicism that characterised England during the reigns of Elizabeth and her successors.

The secret Jesuit missions in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada (1588), the Gunpowder Plot (1605), the periodic Jacobite invasions after 1688, and French involvement in the 1798 rebellion in Ireland all contributed to the popular stereotype of English Roman Catholics as actual or potential traitors. Partly because of a perceived link between Roman Catholicism and absolutism, anti-Roman Catholicism was one of the factors that helped incite the English Civil Wars (1642–49) and the ‘Glorious Revolution’ (1688–89).

Even a century later, when religious tensions had somewhat subsided, violent anti-Roman Catholicism briefly reappeared with the Gordon riots in London (1780). Anti-Roman Catholicism revived in the nineteenth century and was in some ways more significant than earlier manifestations of the prejudice. The vitality of religious conflict in this period has led Arnstein to argue that ‘it is more fruitful to look upon the Victorian conflict between Protestantism and Catholicism as a separate chapter rather than as a mere footnote to studies of the Reformation’, while Paz describes anti-Roman Catholicism as ‘an integral part of what it meant to be a Victorian’.

Many Victorians voiced the standard objections to Roman Catholicism: that the priesthood denied the believer a direct relationship with the Trinity; that Roman Catholics paid more attention to objects and saints than to the Trinity; that Roman Catholicism was not scripturally based; and that Roman Catholics’ blind obedience to priest and Pope predisposed them to prefer absolutist governments. The reinvigoration of anti-Roman Catholicism was partly a response to the increasing numbers of Roman Catholics.

The Roman Catholic population multiplied almost ten times, from 80,000 in 1770 to 750,000 in 1850, or to 3.5 per cent of the population, and became more urban and less dependent on the gentry. Much of the increase was due to the immigration of Irish people: by 1851 Irish Roman Catholics outnumbered English Roman Catholics by about three to one. However, anti-Roman Catholicism was so well-established prior to the 1820s that there was no obvious relationship between the number of Irish and the level of anti-Catholicism in any particular area. Roman Catholics’ higher public profile in the nineteenth century also contributed to the inflammation of prejudices against them.

Catholic emancipation (by the Catholic Relief Act of 1829) allowed Roman Catholic men who met the property requirements to enter Parliament. In the next decades the prayer campaigns for the conversion of England, which included daily repetitions of the Hail Mary, led by the converts Father Ignatius Spencer (born George Ignatius Spencer, a younger son of the second Earl Spencer) and Ambrose Phillips de Lisle (also Ambrose Lisle Phillips), revived the fear that English Protestantism was under assault, a fear that seemed to be confirmed by the restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England in 1850.

This event, popularly derided as the ‘Papal Aggression’, marked the end of the missionary period in England and the regional missionary government, and gave Roman Catholics a leader within their country: Nicholas Wiseman, born a Roman Catholic, who had spent most of his adult life in Rome, first as a student and then as rector at the English College there. His return to London as the new cardinal of Westminster in November 1850, only days before Guy Fawkes’ Day, gave an added intensity to the annual anti-Roman Catholic activities and marked the apogee of public anti-Roman Catholicism in the nineteenth century.

Anti-Roman Catholicism was further fuelled by the conversions of prominent Anglicans. A small number of privileged Anglicans, like Phillips de Lisle and Spencer, converted in the 1820s, but the public impact of these early conversions was limited. Anglicans became seriously concerned in the 1840s, when converts became both more numerous and of more prominent position. The most famous and, for Anglicans, unsettling conversion was that of Newman, in 1845.

His conversion had been some time in coming: dismayed by the 1841 controversy over his Tract 90, which argued at length that there was no contradiction between Roman Catholic doctrine and the 39 Articles, in 1843 he resigned as vicar of the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Oxford. Even with these warning signs, his late-night, rural conversion in October 1845 sent shock waves throughout the Church of England. Tractarians lost one of their most prominent and articulate spokesmen, while their Anglican opponents seized on it as proof that Tractarianism ‘has furnished, and continues to furnish, to Romanism all its most valuable converts’.

…In particular, Anglicans worried that the material aspects of Roman Catholicism would seduce good Protestants. Sinclair warned: ‘Going merely to hear music at the convents and Popish churches often ends in going there to worship ... the excitement of listening to the Stabat Mater and such beautiful music in honour of Mary, is not only profane, but dangerous’. That the prevailing concern was with defections from within rather than assaults from without, when born Roman Catholics far outnumbered converts, suggests that Anglicans perceived weaknesses in their Church.

What Jenny Franchot has noted about anti-Roman Catholicism in antebellum America is also true for Victorian anti-Roman Catholicism: ‘anti-Catholicism operated as an imaginative category of discourse through which antebellum American writers of popular and elite fictional and historical texts indirectly voiced the tensions and limitations of mainstream Protestant culture’. Few were as sanguine as William Lockhart’s grandfather, who, on hearing that his grandson had converted, said: ‘Well, young men take odd courses, now-a-days; he might have taken to the turf.’

More typically, these conversions profoundly affected those involved, whether they remained in the Church of England or became Roman Catholic. Those who converted suffered many hardships, including, as David Newsome has noted, ‘social ostracism, alienation of friends, loss of money, position, and employment’. For twenty years after his conversion Newman did not see Keble and Edward Bouverie Pusey, two close friends with whom he had shared leadership of the Oxford Movement.

The grief felt by those who stayed was expressed by the high churchman and future Prime Minister Gladstone in a letter that in hindsight is doubly sad, given that its receipient, Robert Isaac Wilberforce, was to convert several years later: I do indeed feel the loss of [Henry Edward] Manning, if and as far as I am capable of feeling anything – It comes to me cumulated, and doubled, with that of James Hope. Nothing like it can ever happen to me again. Arrived now at middle life, I never can form I suppose with any other two men the habits of communication ... and dependence, in which I have now for fifteen to eighteen years had with them both.

…Gladstone’s and Wilberforce’s experiences were not uncommon for men of their class, for as Arnstein has observed: ‘Most significant nineteenth-century Englishmen had either a close friend or relative who became a convert to the Roman Catholic faith.’ Many converts were motivated by a search for the authority they believed to be absent from the Church of England. Their pre-conversion attitudes towards the Virgin Mary differed. For some, Marian devotion – or at least the desire for it – preceded conversion.

The year before he converted, Faber begged Newman for permission to pray to the Virgin Mary. (Permission was denied, on the grounds that religious practices should remain distinct.) On a trip to Paris in 1845, Sophia (Sargent) Ryder, whose late sister Caroline had been married to Manning, her husband George, and George’s sister Sophy purchased rosaries. Sophy was given a book of Marian devotions by Manning, who was in Paris at the time. All three Ryders converted in the spring of 1846.

Phillips de Lisle believed that the Virgin Mary encouraged his conversion to Roman Catholicism, which occurred in 1825, when he was 16 years of age. However, Marian devotion was a stumbling-block to others. Newman confessed that even in 1843, when he had essentially given up ministry in the Church of England, ‘I could not go to Rome, while I thought what I did of the devotions she sanctioned to the Blessed Virgin and the Saints.’

Some converts never did develop a warm Marian devotion. Manning, his gift to Sophy Ryder notwithstanding, was one of them. Nevertheless, the Virgin Mary was blamed for many of those conversions. The Anglo-Catholic bishop Edward Stuart Talbot remembered his mother saying ‘that those who went [into the Roman Catholic Church at mid-century] were those who had begun to practise devotions to the Blessed Virgin’.

This displacement conveniently allowed Anglicans to ignore the fundamental issues of ecclesiastical authority that troubled the converts and to dismiss them as having an inferior religiosity. While converts were not necessarily motivated by a desire for more Marian devotion than was allowed in the Church of England, once within the Roman Catholic fold they were likely to practise it. Those converts were a key reason why Marian devotion, which had not been a significant part of recusant Catholicism, revived from the 1830s.

…The increase in Marian devotion may have been, as Susan O’Brien argues, attributable in part to the congregations of French and Belgian nuns who began to establish English houses in the 1830s, and it may also have been, as Barbara Corrado Pope has suggested, an expression of anti-modernism. Regardless of their motivations, in practising Marian devotion the converts enacted on a personal level what was occurring on an institutional level.

In the Roman Catholic Church the century 1850–1950 is called the Marian age because of the many reported Marian apparitions, the declaration of the Immaculate Conception (1854), and a general increase in Marian devotion. Marian devotion had polemical as well as religious uses. Unlike their recusant forebears, who were forced by the legal and social situation to suppress public expressions of their faith, Victorian Roman Catholics were emboldened by their civic equality. Their greater confidence led them to invoke the Virgin Mary as a means to assert their identity as Roman Catholics.

…The Virgin Mary’s prominence in nineteenth-century England was not attributable solely to Roman Catholics, either their theology and devotional practices or the animosity these inspired. Keble’s and Sellon’s desire for limited Marian invocations demonstrates that the development of what came to be called ‘Anglo-Catholicism’ also played a role in generating those controversies. Anglo-Catholicism grew out of the high-church wing of Anglicanism.

High-church Anglicans emphasised ritual, ecclesiastical authority, and the Catholic identity of the Church of England; in politics their interests were often identified with those of the Tory Party. In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, there were three main types of high-church Anglican: traditionalists, Tractarians, and ritualists. Traditional high church Anglicans defended both the English Reformations and the establishment of the Church of England.

They valued the writings of the early church, but they used them conservatively and in conjunction with the reformers, always insisting that Scripture was the basis of belief and that the Established Church had the right to abandon ancient traditions. They (along with many evangelicals) held the mainstream receptionist view of the Eucharist, that is, that Christ was present in the communion elements only to believers rather than to all who partook of the sacrament.

Although its fondness for ritual and tradition could lead to accusations that it was too close to Rome, traditional high-church Anglicanism was characterised by a fierce anti-Roman Catholicism, which was pungently expressed by the declaration of the clergyman Walter Farquhar Hook: ‘I have always hated the Church of Rome as I would hate the bitterest Enemy of my God.’ Other high-church Anglicans declared the Roman Catholic Church to be ‘a grossly idolatrous Church, debasing and enslaving her adherents’, as well as being the ‘twin sister’ of paganism, and they described Roman Catholics as indifferent or irreverent worshippers who had little knowledge of the Bible.”

- Carol Engelhardt Herringer, “Religion, gender, and the Virgin Mary.” in Victorians and the Virgin Mary: Religion and Gender in England 1830-1885

#history#english#victorian#christian#carol engelhardt herringer#religion#victorians and the virgin mary

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toxic Waste — Belfast (Sealed Records)

Photo by John Campbell

Belfast by Toxic Waste

The mid-1980s were crushingly unhappy times in far too many places: El Salvador, Afghanistan, Soweto, Southwest Philly. And so on. But we shouldn’t neglect Belfast. The dominant narrative of the Troubles features a number of signal events from the period: the Bobby Sands-led hunger strike; the bombings at Hyde Park, Regent���s Park and the Grand Brighton Hotel; the Maze Prison escape. For the population of Belfast, everyday life was an ongoing experience of being under the cosh — of the S.A.S., of the U.D.A., of the I.R.A. (and the Provisional I.R.A., and the numerous smaller paramilitary groups espousing loyalty to Ulster, to the Republican cause or to generalized mayhem). Walled-off neighborhoods, guard posts commanded by men with heavy guns, regular patrols of armored vehicles—the city was a de facto warzone. Hence the name of the Warzone Collective, an organization run by a bunch of Belfast anarcho-punks during the mid-1980s and intermittently through to the present. Toxic Waste was a punk band active in the Warzone Collective, and Sealed Records has done us all a very serious solid by reissuing Belfast, an anthology originally released in 1987 that collects a number of Toxic Waste’s songs. It’s a terrific record, documenting some oft-overlooked music from a vital punk scene and its vigorously politicized response to the lifeworld’s chaos and violence.

The songs on Belfast are taken from two moments in Toxic Waste’s development: Side A has been selected from records produced in 1985 and 1986: From Belfast with Blood — The Truth Will Be Heard, a split EP with Stalag 17 released by Mortarhate (run by Londoner punks Conflict); and We Will Be Free, an LP compiling songs by Toxic Waste, Stalag 17 and Asylum, first released by the Warzone Collective. Side B includes tracks from a later session, featuring Toxic Waste’s Roy Wallace alongside members of DIRT, a London-based anarcho-punk band. There are sonic consistencies that render the sounds on both sides comparable, most notably the dual male and female vocals, though on Side A, founding member Patsy sings, and on Side B, you hear Deno from DIRT. For both line-ups, the influence of Crass is palpable, in the interplay of the voices and the relative simplicity of the songs’ constructions — and legend has it that Toxic Waste was created in the aftermath of a 1982 Crass gig in Belfast.

You can draw a fairly direct line from Stations of the Crass (1979) to We Will Be Free to Nausea’s Extinction, from “You’ve Got Big Hands” to “As More Die” to “Godless.” That sort of genealogy building is informative and interesting, but the importance of the immediate social context of Toxic Waste’s music should not be reduced. The situation of anarcho-punks in a politically fraught conjuncture like mid-1980s Belfast lends the music a particular power. Songs like “Tug of War,” “Burn Your Flags” and “Religious Leaders” demonstrate the band’s continual symbolic and ideological displacements, to a marginal in-betweenness, then to a radically placeless outside. As anarchists, the punks in Toxic Waste weren’t Catholics or Protestants, Fenians or Loyalists, natives of Sydenham or of New Lodge. Their relations to Northern Irish identity were infernally complex. There’s this, from “Song for Britain”: “You take a look at Northern Ireland / And think it’s too far away to worry about / But it’s not that far / And you may have to experience what we’ve put up with for years.” That seems like a collective “we,” cutting across the country’s sectarian lines. But in a city so divided, where could that “we” live with any sort of stability? And from whence does the treat in that final clause originate? Then on “We Will Be Free,” you hear, “I am not Irish / I am not British / I am me / I am an individual / Fuck your politics! / Fuck your religion! / I will be free! / We will be free!” Shorn of national, religious and political markers, who is that “We”? Is it the same “we” that speaks in “Song for Britain”?

It’s impossible to say for certain, and all of those contingencies and fluidities make the music on Belfast volatile, always on the move, always riven with restless desire. Perhaps the most coherent statement of the intent driving Toxic Waste can be encountered in “Traditionally Yours” (present on the record in two versions, from the two iterations of the band — a double voicing that further complicates all the other double voicings): “The struggle became a movement / Human rights was its concern / ‘How dare they!’ cried the rich / We’ll see those fuckers burn!” The anarchist language embedded in the passage is as powerful as it is ambiguous. What do we make of the past tense? Does that indicate that the movement is moribund, undone by Northern Ireland’s violence? And what about that “we”? Is it spoken by the song’s lyric speakers, representing the anarcho-punks that sing? Or is that “we” the “rich,” expressing their outrage at and malign plans for the anarchist cause? The syntax remains unresolved, and while Northern Ireland’s worst armed struggles have receded, these songs remain explosive, messages from displaced people that systems of oppression would like to exploit, exhaust and cast aside. But even the most institutionally entrenched powers find that Toxic Waste isn’t so easy to dispose of.

Jonathan Shaw

#toxic waste#belfast#sealed records#jonathan shaw#albumreview#dusted magazine#punk#anarcho punk#ireland

99 notes

·

View notes

Link

Today the richest 40 Americans have more wealth than the poorest 185 million Americans. The leading 100 landowners now own 40 million acres of American land, an area the size of New England. There has been a vast increase in American inequality since the mid-20th century, and Europe — though some way behind — is on a similar course.

These are among the alarming stats cited by Joel Kotkin’s The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, published earlier this year just as lockdown sped up some of the trends he chronicled: increased tech dominance, rising inequality between rich and poor, not just in wealth but in health, and record levels of loneliness (4,000 Japanese people die alone each week, he cheerfully informs us).

Kotkin is among a handful of thinkers warning about a cluster of related trends, including not just inequality but declining social mobility, rising levels of celibacy and a shrinking arena of political debate controlled by a small number of like-minded people.

The one commonality is that all of these things, along with the polarisation of politics along quasi-religious lines, the decline of nationalism and the role of universities in enforcing orthodoxy, were the norm in pre-modern societies. In our economic structure, our politics, our identity and our sex lives we are moving away from the trends that were common between the first railway and first email. But what if the modern age was the anomaly, and we’re simply returning to life as it has always been?

…

Most of the medieval left-behinds would have worked at home or nearby, the term “commuter” only being coined in the 1840s as going to an office or factory became the norm, a trend that only began to reverse in the 21st century (accelerating sharply this year).

…

Along with income stratification, another pre-modern trend is the decline of social mobility, which almost everywhere is slowing (with the exception of immigrant communities, many of whom come from the middle class back home).

Social mobility in the US has fallen by 20% since the early 1980s, according to Kotkin, and the Californian-based Antonio Garcia Martinez has talked of an informal caste system in the state, with huge wage differences between rich and poor and housing restrictions removing any hope of rising up. California now has among the most dystopian of income inequality, with vast numbers of multimillionaires but also a homeless underclass now suffering from “medieval” diseases.

Unfortunately, where California leads, America and then Europe follows.

…

Patronage has made a comeback, especially among artists, who have largely returned to their pre-modern financial norm: desperate poverty. Whereas musicians and writers have always struggled, the combination of housing costs, reduced government support and the internet has ended what was until then an unappreciated golden age; instead they turn once again to patrons, although today it is digital patronage rather than aristocratic benevolence.

A caste system creates caste interests, and some liken today’s economy to medieval Europe’s tripartite system, in which society was divided between those who pray, those who fight and those who work. Just as the medieval clergy and nobility had a common interest in the system set against the laborers, so it is today, with what Thomas Piketty calls the Merchant Right and Brahmin Left — two sections of the elite with different worldviews but a common interest in the liberal order, and a common fear of the third estate.

…

Tech is by nature anti-egalitarian, creating natural monopolies that wield vastly more power than any of the great industrial barons of the modern age, and have cultural power far greater than newspapers of the past, closer to that of the Church in Kotkin’s view; their algorithms and search engines shape our worldview and our thoughts, and they can, and do, censor people with heretical views.

Rising inequality and stratification is linked to the decline of modern sexual habits. The nuclear family is something of a western oddity, developing as a result of Catholic Church marriage laws and reaching its zenith in the 19th and 20th centuries with the Victorian cult of family and mid-20th century “hi honey I’m home” Americana. Today, however, the nuclear household is in decline, with 32 million American adults living with their parents or grandparents, a growing trend in pretty much all western countries except Scandinavia (which may partly explain the region’s relative success with Covid-19).

This is a return to the norm, as with the rise of the involuntarily celibate. Celibacy was common in medieval Europe, where between 15-25% of men and women would have joined holy orders. In the early modern period, with rising incomes and Protestantism, celibacy rates plunged but they have now returned to the medieval level.

The first estate of this neo-feudal age is centred on academia, which has likewise returned to its pre-modern norm. At the time of the 1968 student protests university faculty in both the US and Britain slightly leaned left, as one would expect of the profession. By the time of Donald Trump’s election many university departments had Democrat: Republican ratios of 20, 50 or even 100:1. Some had no conservative academics, or none prepared to admit it. Similar trends are found in Britain.

Around 900 years ago Oxford evolved out of communities of monks and priests; for centuries it was run by “clerics”, although that word had a slightly wider meaning, and such was the legacy that the celibacy rule was not fully dropped until 1882.

This was only a decade after non-Anglicans were allowed to take degrees for the first time, Communion having been a condition until then. A similar pattern existed in the United States, where each university was associated with a different church: Yale and Harvard with the Congregationalists, Princeton with Presbyterians, Columbia with Episcopalians. The increasingly narrow focus on what can be taught at these institutions is not new.

Similarly, politics has returned to its pre-modern role of religion. The internet has often been compared to the printing press, and when printing was introduced it didn’t lead to a world of contemplative philosophy; books of high-minded inquiry were vastly outsold by tracts about evil witches and heretics.

The word “medieval” is almost always pejorative but the post-printing early modern period was the golden age of religious hatred and torture; the major witch hunts occurred in an age of rising literacy, because what people wanted to read about was a lot of the time complete garbage. Likewise, with the internet, and in particular the iPhone, which has unleashed the fires of faith again, helping spread half-truths and creating a new caste of firebrand preachers (or, as they used to be called, journalists).

…

English politics from the 16th to the 19th century was “a branch of theology” in Robert Tombs’s words; Anglicans and rural landowners formed the Conservative Party, and Nonconformists and the merchant elite the core of the Liberal Party. It was only with industrialisation that political focus turned to class and economics, but the identity-based conflict between Conservatives and Labour in the 2020s seems closer to the division of Tories and Whigs than to the political split of 50 years ago; it’s about worldview and identity rather than economic status.

Post-modern politics have also shaped pre-modern attitudes to class. In medieval society the poor were despised, and numerous words stem from names for the lower orders, among them ignoble, churlish, villain and boor (in contrast “generous” comes from generosus, and “gentle” from gentilis, terms for the aristocracy). Medieval poems and fables depict peasant as credulous, greedy and insolent — and when they get punched, as they inevitably do, they deserve it.

Compare this to the evolution of comedy in the post-industrial west, where the butt of the joke is the rube from the small town, laughed at for being out of touch with modern political sensibilities. The most recent Borat film epitomises this form of modern comedy that, while meticulously avoiding any offence towards the sacred ideas of the elite, relentlessly humiliates the churls.

The third estate are mocked for still clinging to that other outmoded modern idea, the nation-state. Nation-states rose with the technology of the modern day — printing, the telegraph and railways — and they have been undone by the technology of the post-modern era. A liberal in England now has more in common with a liberal in Germany than with his conservative neighbour, in a way that was not possible before the internet.

Nations were semi-imagined communities, and what follows is a return to the norm — tribalism, on a micro scale, but tribalism nonetheless, whether along racial, religious or most likely political-sectarian tribes. Indeed, in some ways we’re seeing a return to empire.

…

The middle-class age meant the triumph of bourgeoise values and the decline of the middle class has led to their downfall, widely despised and mocked by believers in the higher-status bohemian attitudes. Now the age of the average man is over, and the age of the global aristocrat has arrived.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanksgiving

The first "thanksgiving" happened in October of 1621, but the constructed history and significance of that event has been over 500 years in the making. When I was a child I liked Thanksgiving because it meant family time. When I became a man I felt angered and betrayed by the truth of the holiday. Now, as a father, I see Thanksgiving as a teachable moment - a chance to properly frame the history of the day while still enjoying time with my two boys, my wife, and my family. Holidays are a wonderful chance to remember where we come from, what is important to us, and how we got where we are. Mark Twain is attributed as saying something to the effect of "history doesn't actually repeat itself, but it often rhymes." Thanksgiving gives us a lot of opportunity to reflect on this.

In order to better understand the first Thanksgiving, we start nearly 100 years earlier in the 1530s. The King of England, Henry VIII, wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (she was the first of what would end up being six wives), but the Pope wouldn't allow it. So the King declared that the Pope was no longer the head of the church. This set England on a path that renounced Catholicism in favor of the Church of England as the ultimate religious authority, and set the King as the head of that Church. 100 years later, it was not acceptable in England to be any sort of Christian other than as part of the Church of England.

The King of England was a powerful man who may have usurped a religion to get what he wanted. The religious intolerance of England back then echoes to recent times as strife between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland. And while today England is full of people who are allowed to practice other religions, it is interesting that in 1620 the pilgrims to America were the "wrong kind" of Christian to be in England. (Perhaps there will always be "wrong kinds" and "others" in our society, and perhaps the test of our virtue isn't in the certainty of our beliefs, but in our tolerance for alternatives.)

Intolerance was a problem for the group of Christians who would become the Pilgrims, and that intolerance ran both ways. They wanted to be separate from the Church of England, and to worship in their own way. But such dissent would not be tolerated and they were persecuted. So they fled England and moved to Holland where there was some acceptance for differences in religion. However, these separatists didn't like their children learning dutch and adopting dutch culture. They found it hard to integrate with Dutch society while retaining strict adherence to their own specific religious and cultural doctrine. So the decided they needed to move again.

The Separatists were immigrants in Holland, but without the willingness to integrate they could not make Holland their home. They themselves were intolerant of their new host country. England wouldn't tolerate them. They wouldn't accept Holland. And they refused to change themselves. Their self-imposed isolation led them to the idea that they could be left alone in America, and land with no King, to do as they pleased... and they intended to establish a new society based on their specific and strict religious and cultural beliefs.

So they worked out a deal with England (and I am simplifying this a bit). England would give them passage to America, where they would prosper and work off the debt for this passage by sending surplus back to England, to the profit of the investors. Because of this, the Pilgrims weren't the only people on the Mayflower. With them were indentured servants they forced to come along, and some "company men" who were responsible for seeing to the financial success of the colony. In their journals, the pilgrims referred to these people, with whom they would have to live and work, as "the strangers".

So the forces that brought the pilgrims to America were both religious and financial. Here was a group of people divided between those seeking to create and spread their idea of a religious haven, and those who wanted to make money.

Fortunately the obvious conflict came to a head early, and before they stepped off the boat to start their new colony they wrote and signed the Mayflower Compact, which established a secular government for the colony. The leadership for the colony would not rest in religion, but would be shared by all. Well... not all... 41 men signed, out of the 101 total passengers on the ship. Women, indentured servants, and children were not given authority to participate in the compact and did not sign it.

But this story isn't just about Pilgrims, it's also about the New World: America, and the people who already inhabited it. While it's likely Norse sailors (specifically Leif Ericson around 1003) were the first Europeans to North America, Christopher Columbus is the most well known. Ponce de Leon was the first to reach what would become the United States. These explorers and those that followed brought with them horrible epidemics of disease, for which the native population had no defenses. Not only were their immune systems unprepared for the new diseases, they had no experience or medicine for treating these new illnesses. There is no conclusive estimate of the population of Native Americans living in what would become the United States before European explorers arrived, but credible attempts have estimated a population as low as 2 million, and as high as 18 million. Similarly, we can't know how many died to disease, but we do know that whole villages disappeared after the arrival of the Europeans. And we know that by 1900 there were only about 250,000 Native Americans left. Which means that 400 years after Europeans arrived, the population of Native Americans was reduced by somewhere between 90 and 99%, with some tribes disappearing entirely.

When the first settlers started to arrive, they weren't coming to an empty continent. They were coming to a place where people had been living for thousands of years. They had trails, and traded with one another. They had separate and distinct cultures and languages. They had specialized skill sets and industries. But now they were all being devastated by unrelenting waves of epidemic disease and war brought by visitor after visitor looking to exploit the resources of the new world. Those that survived smallpox were still vulnerable to measles, and plague, and new variants of influenza. Imagine wave after wave of disease killing half or more of the population over and again. Those who didn't die still got sick. Who gathered the food? Who tended to the ill? It was devastating to the people, and their cultures. Their infrastructure crumbled, their population reduced, and their way of life was decimated. The effect of such devastation to the psyche of a people is beyond imagining.

And so it was when the Mayflower arrived 130 years after the first explorers. On their first two expeditions ashore the pilgrims found graves, from which they stole household goods and corn - which they would plant in the spring. On their third expedition they encountered natives, and ended up shooting back and forth at each other (bows versus muskets). The Pilgrims decided they didn't want to settle in this area, as they had likely offended the locals with their grave robbing and shootout, so they sailed a few days away. They found cleared land in an easily defended area and began their settlement. This fantastic location was no happy accident. Just three years previous this place was called Patuxet, now abandoned after a plague killed all of its residents. The Pilgrims will say they they founded Plymouth, but it might be more accurate to say they resettled Patuxet.

By the time the Pilgrims found Patuxet it was late December, and they huddled in their ship barely surviving the brutal, hungry first winter. By march only 47 souls survived, though 102 had left port 6 months before.

There were, roughly, three different groups of local Natives. They had been watching the pilgrims carefully all winter, just as the pilgrims had been watching them. In the days before there had been frightening encounters between pilgrims and natives, and the pilgrims were rushing to install a cannon in their emerging fortification. They were on high alert, and expecting confrontation. Given the history, mutual fear, and mistrust, a violent encounter between the two groups seemed imminent and unavoidable.

The story many of us were told is that Squanto and a group of Indians approached the pilgrims, as if neither had ever seen the other before, and in greeting Squanto raised his hand and said, "How". The actual truth is that a visiting chief named Samoset strode, alone, into the middle of the budding and militarizing pilgrim town and said, "Welcome Englishman." And then he asked for a beer. (Truth.) It turns out Samoset was visiting local Wampanoag chieftain Massasoit, and he spoke some broken English, which he had learned from the English fishermen near his home. He took it upon himself to open negotiations with the new settlers. He told them about the local tribes, and brokered an introduction to Chief Massasoit, with whom the pilgrims ultimately signed a treaty.

Along with the treaty came Squanto, a Native American originally from the now defunct Patuxet tribe. Squanto was invaluable to the Pilgrims. Not only could he act as a translator, but he also knew the local tribes and the area itself. It was where he grew up. He knew what food was available, what crops to plant and how, and he knew not only the language but the disposition and history of local tribes. Speaking with the locals isn't enough if you can't discern their desires and motives. Squanto was a great friend to the English Pilgrims, and acted in their interests, sometimes to his own peril.

How did Squanto learn English language and culture? Squanto had been kidnapped by the English captain Thomas Hunt in 1614. Hunt abducted 27 natives, Squanto among them, which he sold as slaves in Spain for a small sum. These hostilities, just years before the arrival of the Pilgrims, are the reason for the initial animosity and aggression toward the English Pilgrims when they arrived, and why the natives were wise enough to attack the English, even if their bows were not a match for English muskets. Exactly how Squanto survived in the old world, or how he got from Spain to England, is unclear. It is known that a few years after his abduction, Squanto was "working" (likely as an indentured servant) for Thomas Dermer of the London Company. Dermer brought Squanto back to the location of the Patuxet village in 1619 as part of a trade and scouting venture, but the village had been wiped out by disease. After acting as translator and negotiator for Dermer on that trip, the now homeless Squanto stayed in America and went to live with Pokanoket tribe. The terms of this arrangement are not clear. It is possible Squanto was a prisoner of the Pokanoket, and that he was "given" in a trade that allowed the Dermer to exit a dangerous situation. Regardless, Squanto chose to live out the rest of his life with the Pilgrims in his childhood home of Patuxet, now renamed Plymouth by the (re-)colonizing English Pilgrims. Whatever the exact details, Squanto was one of the most traveled men in the area - having been born in America and spending time in Spain, England, and Newfoundland.

Squanto's time with the pilgrims appears full of adventures. He was sent as an emissary for peace and trade on behalf of the pilgrims to numerous tribes. It also appears he leveraged his influence among the Europeans to make some of his own demands from these tribes, which drew the ire of many local tribal leaders. Chief Massasoit even called for Squanto's execution. When William Bradford (Plymoth's Governor) diplomatically refused, Massasoit sent a delegation to retrieve Squanto from the Pilgrims. Again Bradford refused, even when offered a cache of beaver pelts in exchange for Squanto, with Bradford saying, "It was not the manner of the English to sell men's lives at a price”. Squanto was very valuable to the Plymoth colony, but he died in 1622 of "Indian fever".

In October (most likely) of 1621 the Pilgrims celebrated their first harvest. The was indeed a harvest feast attended by 90 Native Americans and 53 Pilgrims. Both groups brought food and games to the three day celebration. But this was not the start of the Thanksgiving holiday in America. It was a harvest festival, and harvest was common ground that both cultures celebrated. The American holiday of Thanksgiving was first celebrated as such when George Washington and John Adams declared days of thanksgiving during their presidencies. This was followed by a long period where subsequent Presidents did not declare such events. A writer and editor named Sarah Hale, most famous for penning "Mary Had a Little Lamb", began to champion the idea of a national "Thanksgiving" holiday in a 17 year campaign of newspaper editorials and personal letters written to five different Presidents. Perhaps because of her insistence and the popularity she garnered for the idea, Abraham Lincoln revived Thanksgiving as a unified national holiday in 1863. A few years later Congress enshrined it as a national celebration on the 4th Thursday of November.

And this is my Thanksgiving. It's not the simpleton's story of an awkward greeting followed by a good meal. It's the story of a King who wanted a divorce, religious self-righteousness, the greed of men, a clash of cultures, a struggle for survival, loyalty and betrayal, the creation of a national holiday intended to help mend a nation torn apart by civil war, and the myths we created to tie us all together. As always, truth is a much more engaging and explanatory than a politely shared fiction.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Da Vinci Code: A Better, Smarter Blockbuster Than You Remember

https://ift.tt/3spUWqg

I didn’t get it. When Ron Howard’s The Da Vinci Code took the world by storm in 2006, I was far from being a professional critic, but I could still be highly critical of something like this. It was an adaptation of the biggest literary phenomenon of the decade not starring Harry Potter, and it was arriving in cinemas with the kind of media frenzy usually reserved for Star Wars. All the while, its rollout suggested it had aspirations to be an awards contender. How could something that high-handed live up to that kind of hype?

As a splashy Hollywood version of Dan Brown’s most popular potboiler, The Da Vinci Code premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May and was the subject of countless faux-examinations about early Christianity on the cable news circuit—as well as the object of ire for some modern Christians’ growing need for perpetual outrage. Protests occurred at theaters throughout the U.S., while other international markets banned it outright. And all of that cacophonous noise was over… a pretty middle-of-the-road adventure movie. One that features Tom Hanks earnestly looking into the camera to declare “I need to get to a library!” as the music swells. Really?!

So, yes, I missed the appeal. And judging by the infamous catcalls the movie received at Cannes, which were followed by a tepid critical drubbing in the international press, I wasn’t alone in thinking the movie amounted to a lot of overinflated hoopla.

But a funny thing happened when I sat down to watch it on Netflix the other day, about 15 years after its release: I realized what a big goofy delight the movie could be with the right mindset, and what I as a teenager—and so much of the contemporary film press during its time—missed out on.

To be sure, The Da Vinci Code is still a ludicrous story that both benefited from and was weighed down by the sensationalism of its conceit. Written on the page by Brown like any other airplane-ready page-turner, with nearly each short chapter ending to the implicit musical sting of “dun-dun-DUN!,” the book is a pleasantly conceived time-filler. It’s about secret societies, dastardly supervillains, and a matinee idol for the academia set named Robert Langdon. Essentially Indiana Jones if Harrison Ford never took off the tweed jacket, Langdon is an expert in the real world field of art history and the fictional one of symbology, and his monologues give the proceedings a nice bit of pseudo-intellectual window-dressing. It’s all no more challenging to the viewer (or their storyteller) than the background details provided by M in James Bond flicks.

This formula turned Brown’s first Robert Langdon novel, Angels & Demons, into a literary hit, but what made The Da Vinci Code an international phenomenon—and thereby grabbed Hollywood’s attention—was the kernel of a brilliantly explosive idea: What if the MacGuffin in the next story wasn’t some abstract relic from antiquity but something that would challenge our very idea of Christianity today? What if the story of the “Grail Quest” turned out to be evidence that Jesus Christ was married? And what if Christ had children by that marriage?

And, finally, what if the evil “Illuminati” baddies here were an offshoot of the Catholic Church wanting to cover it all up?

Brown derived this twist from the research of Lynnn Picknett and Clive Prince in The Templar Revelation, a highly speculative text which posits the relationship between Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene has been downplayed for millennia by the Catholic Church, beginning with the Council of Nicaea—the ecumenical Roman council in 325 C.E. that essentially decided which early Christian texts would comprise the New Testament and which would not—and continued through Leonardo da Vinci secretly placing Mary Magdalene in his “The Last Supper” mural by putting her at the right hand of Christ. In an era with a growing interest in conspiracy theories, this one was the mother lode.

Brown took these fringe theological ideas and gave them an erudite sheen in The Da Vinci Code while still essentially writing a piece of fluff. It’s an international escapade where the MacGuffin is the most interesting element.

This made for an addictive beach read, but in Howard and Sony Pictures’ pricey movie adaptation, the pretenses were heightened to operatic levels. Consider the way Howard and cinematographer Salvatore Totino bask in the oppressive shadows entombing the frame whenever Paul Bettany’s murderous Brother Silas appears on screen. As a homicidal albino monk, Silas wouldn’t look out of place battling Roger Moore over nuclear codes. But Howard’s film plays it completely straight by coveting each shot of Silas’ self-mutilations and prayers, and by suggesting the character has something profound to say about the zealotry of religion (or perhaps just the Catholic sect of Opus Dei).

Similarly, Hans Zimmer writes a lush ecclestial score throughout the film, seeming to imply this is some mighty exploration of religion, and a study in the conflict between faith and skepticism. After all, the doubting Langdon is forced to revisit his Catholic School youth when he discovers his new friend is the direct descendent of Jesus Christ.

That all these elements ultimately act as scaffolding for a popcorn movie in which adults can indulge in entertaining a little heresy, or at least give lip service to religious introspection while also cheering the car chases and convoluted plot twists, turned off plenty of critics. Yet it’s fair to now wonder if such middlebrow pleasures simply went over some heads?

As a film, The Da Vinci Code is a lot more basic than its presentation suggests. Nevertheless, there is an intriguing premise at its heart that made it an international watercooler discussion in the first place, and the perfect culture war lightning rod of the Bush years.

While I wish Brown did more with the megaton-potential of his setup, he nevertheless provided an unusually brainy foundation for his potboiler. One in which subjects like medieval history, early Christian theology, and the treasures of the Louvre were put front in center in pop culture, as opposed to superheroes and space wizards.

Read more

Movies

How the Passion of Hannibal Lecter Inspired a New Opera About Dante

By David Crow

Movies

Inferno – Ron Howard Talks About Changing the Ending

By Ryan Lambie

It’s still a frustration that The Da Vinci Code and its sequels abandoned his pearl of a MacGuffin right when its intrigue was at its highest. Genuinely, what would you do if you discovered you’re the last living descendent of Christ and can change the world religions with a single DNA test? Even so, rather than relying on ultimately meaningless plot devices like magical space stones, or cursed pirate treasure, Brown’s story caused audiences to examine the foundations of their world, and the origins of the tenets that might guide their lives.

Whether or not the Templar Order really found the remains of Mary Magdalene and realized she was the bride of Christ, the origins of what is and is not Christianity, or Christlike, being decided by a bunch of acrimonious bishops at Nicaea challenges viewers to more seriously interrogate what they accept as handed down gospel. And the millennia-long persecution of women touched upon in The Da Vinci Code ferrets out the enduring realities of modern gender dynamics, even if Brown and Howard tack a wacky and amusing conspiracy theory on top of it.

The Da Vinci Code is popcorn soaked in bombastic media hype, but it still leaves you with more to digest than the type of mainstream blockbuster spectacles that have replaced it in the last 15 years—often while receiving far less rigorous criticism from the modern film press.

Consider how in the pivotal scene on which The Da Vinci Code turns, Ian McKellen makes a meal out of the reams of exposition he’s handed. It’s left to McKellen’s mischievous smile to sell and explain the vast historical background that informs the film’s thesis. In most modern blockbusters, these scenes have been reduced to the perfunctory—bare bone obligations that must be met as quickly and unexceptionally as possible. But the narrative mystique that occurs when such exposition is handled with awe is at the very heart of The Da Vinci Code, and the movie sparks to life within the twinkle of McKellen’s eye.

“She was no such thing,” McKellen’s Sir Leigh Teabing bellows when the misconception of Mary Magdalene being a prostitute is mentioned. “Smeared by the Church in 591 Anno Domini, the poor dear. Magdalene was Jesus’ wife.” The anger in McKellen’s voice perhaps betrays an all too personal knowledge of the mistruths spread in the name of religious orthodoxy. And when he asks other characters to “imagine then that Christ’s throne might live on in a female child,” audiences are likewise invited to conspire–dreaming of the potential real world implications of an otherwise wild fantasy.

It may not be great art or history, but The Da Vinci Code uses both to offer a great time—or at least a pretty good one where Paul Bettany is depicting obsession with God instead of cosmic cubes. And 15 years later, after its era of star-led spectacles has passed, the picture still works as a blockbuster meant to entertain adults with at least a passing interest in issues more mature than what they used to talk about on playgrounds. Given the state of modern Hollywood tentpoles, that sounds blasphemous, indeed.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post The Da Vinci Code: A Better, Smarter Blockbuster Than You Remember appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3uxzMIJ

0 notes

Text

Pure waste of bandwidth

A few Girard-inspired, mathematical-theological stories for my friends.

Voting for itself. Girard dismisses the Hilbert’s programme, comparing the attempt to prove mathematics using mathematics to “the parliament voting for itself”. It is a correct comparison, yet its value as a criticism is ambiguous. As a french logician, Girard might actually know that the French Republic – and arguably the modern politics – has actually been founded with the parliament voting for itself. In 1789, the new-founded National Assembly of France was concerned with the question, whether it actually does represent the general will? This question was resolved affirmatively by the notorious Abbé Sieyès, who took the structure of his argument from the catholic thinker Nicolas Malebranche.

Malebranche was concerned with proving prothestants wrong, as catholics usually are. The problem was, whether the Catholic Church, that is, its body of cardinals was the one, unique representation (in the yet religious sense, from which we will later found the legal concept of representation) of God on Earth – as opposed to the possibility of the multiple, partial, conflicting representations of his will favored by the protestants. His thought experiment was simple: “Say we gather all of the cardinals together and let them take a vote, whether they, together, do or do not represent the god’s will. The ones who say ‘no’ are obviously not real cardinals: you can’t be a cardinal if you don’t believe in the institution. So everyone who is a real cardial will say ‘yes’, thus determining by unanimous vote that the Catholic Church is indeed the one and unique representant of God”.

Now let us postpone the matter of the obvious begging-the-question; let us also not indulge for now in the beautiful ways with which Malebranche tries to fix it; let’s focus on how this argument is still at work in our very lives. Abbé Sieyès used this very same argument to prove that the Assembly is the real representative: if your particular will is against it, you’re just not of the Republic and your will doesn’t count. The whole seeming ridiculousness of the argument pales in comparison with its incredible effectiveness: the modern politics was born with all its representative-democratic weirdness. There’re likely philosophical ways to ground this idea onto something more fundamental, yet the notoriousness of such an ouroboric event is clear, and the break that happened here is on the level of a new self-supporting thought from which, however, the ‘real things’ are being created on a daily basis.

Can’t we say that Hilbert’s programme is the same type of event, just imposed kind of retrospectively onto the history of mathematics? The mathematics voting for itself, let the naysayers be damned into luddistic hell? In this case we can go on living with its theological form while embracing the fruitful mathematical content it gave us. And then our next move, the move of the ones who dares to respect and use mathematics without believing in it, should obviously be to look for the heretics and the heretical thoughts. We should not be content with those who just dismisses mathematics altogether (the boring, impotent atheists) – the real heretic is the one who is of the mathematical practice, but questions its belief structure. How do you call the hagiography but about heretics? Heretography?

Hysterizing the computer. Now one of those heretics is Brouwer, whose whole project was about questioning the givenness of the a priori. Insane idea, completely against Kant, of course, as it questions the very distinction between thinking and praxis. A priori as something completely given assumes some kind of a collapse of the process of thinking in time, with all of the theorems already there somewhere, indeed nothing more than Anselm’s ontological argument, but about mathematics. Brouwer scouted this a priori and found his own fixed point theorem, which states that there’s something that exists but can’t be found. Now that’s unsettling for Brouwer who is, by the way, of a Schopenhauer’s persuasion. To question the whole thing, Brouwer looks for the most extreme point of this a priori givenness, and it’s nothing else but the law of the excluded-middle: it’s only there if you can always do the anselmnian jump to the farthest conclusion. Brouwer slows down this seemingly instantaneous jump by denying it, inventing the intuitionistic logic, and actually somehow manages to get pretty far with it, reformulating even a part of topology in this new light. However this heresy was not approved by his holiness Hilbert, already too influential on the continent – isolated Brouwer loses his mind and dies, never seeing any hope of his work being useful.

A different development was up at the same, however, concerned a piece of metal to be called computer. There were a few of those machines already, and it was obvious that there’s going to be more. On the other hand, it didn’t actually take very long for people to notice how incredibly useful the intuitionistic logic was for this machine: much more than the ‘classical one’. The computer became the redeeming object of Brouwer’s logic – he never saw one, never even thought of one, yet turned out to provide the most important concept for its study. The depth of Brouwer’s premature contribution to Computer Science is beyond the wariness of tertium non datur: his work predicted the notorious problems with the floating-point numbers, and his topology turned out to be a weird tool to study computable functions, which is a cross-sub-disciplinary link of strange awesomeness for the easily excitable people like me.

So if we’re desperately looking for any escape from the horrible weight of the Kantian-Hilbertian mathematical theology, shouldn’t we look into the computer? One of the weird things about the computers is how easily we all were persuaded, not so long ago, that everything in the computer is “virtual” (not in the sense in which philosophers use the epithet, but in the sense the marketers use it), that is, not exactly material… Which is nonsense, a structure of disavowal, which has to be thoroughly contradicted on all the levels, starting on the level of primitive processor instructions which, according to the simplest laws of thermodynamics, can’t perform any destructive operation – can’t forget any value of any variable – without wasting some energy, emanating some heat. This kind of thought is as material as it can be.

Right here, right now, I can show you how the materiality of computer affects our everyday life in a very noticeable, annoying fashion. Let us recall that to study the whole population of computers a special concept was invented, ‘the Turing machine’. It was a strange abstraction, seeking to provide an ideal type for those machines, a link between their real bodies and the computable functions which are performed by them. It is used in science, yes, but it is also used too much in the arguments between the adolescent programmers, if you ever dared to talk to them – “C and Lisp are the same thing because of the Turing machine”... But let’s leave them be. Where’s the Turing machine’s fault?

Turing machine is imagined to have an infinite time and an infinite memory space. That’s what we can sometimes believe about our computers. When our computers run out of time – that is, we subjectively feel that they are slow – we’re annoyed and happy to fix it. The existence of the computer as a time-consuming device is obvious and we’re perfectly equipped to notice it; every second it’s slowing down we’re feeling it, I think, already at the level of our bodies; yet there’s no realistic limit to how long a computer can run. What is harder to notice, yet much more objective, is the limit of its memory: the computer runs just happily, using as much memory as it can, until there’s no more memory at all. Then strange things begin to happen.

What does exactly happen when the computer is out of memory? Of course, it can just kill the hungry program: it’s not part of the algorithm’s mathematical abstraction, but at least predictable. Usually, however, stranger things happen. One of the ways the computer pretends to have more memory than it actually does is by “swapping”: using the HDD instead of the RAM to store whatever is to be stored in memory. HDD is 10k times slower than RAM: when it’s used for memory too much, nothing crashes, but everything is suddenly very slow. We hear strange noises. The computer starts misbehaving. Random things crash because of the timing issues brought by the lack of speed.

Now we can allow ourselves to see this “lack of memory” in the aristotelian-lacanian light, as something that is material by being actively opposed to the (mathematical) form, not-reducible to it (if only to escape the attempt to inscribe the whole OS, other programs and the hardware into one big ad hoc mathematical structure making any mathematical study of the algorithms pretty much useless). I say “lacanian”, faithfully to Lacan (his Real was Aristotle’s matter), because this is indeed the very point where the subjectivity of computer in the lacanian sense is obvious: it lacks memory (desire) – it acts out (hysteria). If we consider how hackers use a similar problem, the buffer overflow, to do whatever they want to the computer, the analogy becomes rich enough.

The materiality of the neural network. In 1892, one W. E. Johnson described “symbolic calculus” as “an instrument for economizing the exertion of intelligence” (btw, Johnson is described by Wikipedia as “a famous procrastinator”). Far from enabling new types of intelligence by itself, the thing was to save on the wasted expenditure of the old ones. With this I want to introduce another dimension of the materiality of the computer: the one which I’ll describe from a paranoid-marxist perspective, following the Adorno’s belief in the truth of the exaggerations.

Neural network is an amazing shiny new thing, it economizes our exertion of intelligence all right, yet the weirdest part of it all is that we kinda have no idea how it works. We can describe the output (in our terms which we impose on it), and we can describe the inner structure (it’s all matrix multiplication), but there’s no translation between the output and the inner structure except for the one that is by running the neural network themselves. The neural network’s thinking, in general, lacks the conceptual content we’re so much used to, it doesn’t exactly distinguish the parts of bodies and stuff like that. It operates on a belated, not-yet-conceptual level. We can actually through pain identify some general things that it actually notices on the images and stuff like that, but only partially and constantly recognising that it’s we who’s pulling the vague ideas of the NN to this conceptual level.

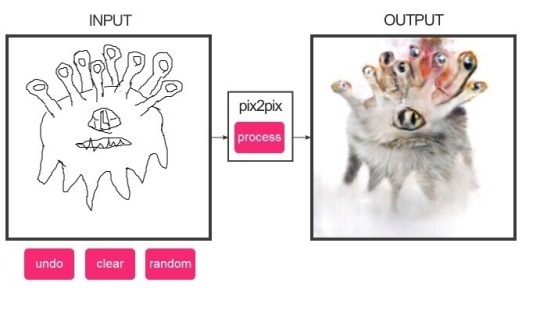

To illustrate how the NN works there’s no better example than the notorious network which draws cats upon sketches of cats: http://affinelayer.com/pixsrv/index.html . Try it out, you can do it online. Now, what are the concepts with which the neural network thinks about cats? It’s… well, it knows an eye, but that’s more-or-less it. Everything else is more like a texture of a cat, in a very weird sense of a texture, the one available to us after we discovered the 3D rendering.

So there’s knowledge of things in the NN, yet it’s either not on the human level, or it’s somehow hidden. To explain this, Schopenhauer comes to mind: “an entirely pure and objective picture of things is not reached in the normal mind, because its power of perception at once becomes tired and inactive, as soon as this is not spurred on and set in motion by the will. For it has not enough energy to apprehend the world purely objectively from its own elasticity and without a purpose”. That is to say: NN understands cats exactly as much as it needs to (with the need imposed by its operators, most of the time the Capital), and no more.

Now the paranoid-marxist intervention: what is this lack of knowledge? Who has it? Is it not the proletariat? If we have a training set of thousands of pictures, on which a neural network is trained to recognize dozes of features, those features had to be tagged beforehand by some pure workers (most likely from India, am i right?), who themselves were likely constructed through a cheap-labor marketplace such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (the name familiar from Walter Benjamin), pretending to be machines to create a neural network which pretends to do the human work. Can’t we say, exaggerating, that the neural network is a labyrinth of numbers in which anyone looking for the human [labor] is to lose his track?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A STATEMENT FROM CHRISTIAN ETHICISTS WITHOUT BORDERS ON WHITE SUPREMACY AND RACISM

The following statement was written by over 250 concerned Christian ethicists and theologians, including several Daily Theology members.

For a full and updated list of signatories, please see click here.

A Statement from Christian Ethicists Without Borders

on White Supremacy and Racism

August 14, 2017

As followers of Jesus Christ and as Christian ethicists representing a range of denominations and schools of thought, we stand in resolute agreement in firmly condemning racist, anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim, and neo-Nazi ideology as a sin against God that divides the human family created in God’s image.

In January of 2017, white nationalist groups emboldened by the 2016 election planned an armed march against the Jews of Whitefish, Montana. On August 11th and 12th, hundreds of armed neo-Nazis marched in Charlottesville, Virginia. As we mourn the deaths of 32-year old counter-protester Heather Heyer and state troopers H. Jay Cullen and Berke Bates from this most recent incident, we unequivocally denounce racist speech and actions against people of any race, religion, or national origin.

White supremacy and racism deny the dignity of each human being revealed through the Incarnation. The evil of white supremacy and racism must be brought face-to-face before the figure of Jesus Christ, who cannot be confined to any one culture or nationality. Through faith we proclaim that God the Creator is the origin of all human persons. In the words of Frederick Douglass, “Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.”

The greatest commandments, as Jesus taught and exemplified, are to love God and to love our neighbor as ourselves; and so as children of God, and sisters and brothers to all, we hold the following:

We reject racism and anti-Semitism, which are radical evils that Christianity must actively resist.

We reject the sinful white supremacy at the heart of the “Alt Right” movement as Christian heresy.

We reject the idolatrous notion of a national god. God cannot be reduced to “America’s god.”

We reject the “America First” doctrine, which is a pernicious and idolatrous error. It foolishly asks Americans to replace the worship of God with the worship of the nation, poisons both our religious traditions and virtuous American patriotism, and isolates this country from the community of nations. Such nationalism erodes our civic and religious life, and fuels xenophobic and racist attacks against immigrants and religious minorities, including our Jewish and Muslim neighbors.

We confess that all human beings possess God-given dignity and are members of one human family, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, or country of origin.

We proclaim that the gospel of Jesus Christ has social and political implications. Those who claim salvation in Jesus Christ, therefore, must publicly name evil, actively resist it, and demonstrate a world of harmony and justice in the midst of racial, religious and indeed all forms of human diversity.

Therefore, we call upon leaders of every Christian denomination, especially pastors, to condemn white supremacy, white nationalism, and racism.

Contemplate and respect the image of God imprinted on each human being.

Work across religious traditions to reflect on the ways we have been complicit in upholding and benefiting from the sins of racism and white supremacy.

Pray for the strength and courage to stand emphatically against racism, white supremacy, and nationalism in all its forms.

Participate in acts of peaceful protest, including rallies, marches, and at times, even civil disobedience. Do not remain passive bystanders in the face of the heresies of racism, white supremacy, and white nationalism.

Engage in political action to oppose structural racism.

We will bring the best of our traditions to an ecclesial and societal examination of conscience where rhetoric and acts of hatred against particular groups can be publicly named as grave sins and injustices.

Finally, as ethicists, we commit—through our teaching, writing, and service—to the ongoing, hard work of building bridges and restoring wholeness where racist and xenophobic ideologies have brought brokenness and pain.

(If you are a Christian ethicist or teach Christian ethics and wish to add your name, please email Tobias Winright at [email protected] or Matthew Tapie at [email protected] or Anna Floerke Scheid at [email protected] or MT Dávila at [email protected] with your name, highest degree, title, and institution. Institutions are named for identification purposes only and this does not necessarily represent their support of this statement, although we hope they do, too.)

For a full updated list of signatories, please click here:

Signed (as of 8/15/17 at 9:PM),

MT Dávila, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Christian Ethics, Andover Newton Theological School

Anna Floerke Scheid, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, Duquesne University

Matthew A. Tapie, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Theology, Director, Center for Catholic-Jewish Studies, Saint Leo University

Tobias Winright, Ph.D., Mäder Endowed Associate Professor of Health Care Ethics and Associate Professor of Theological Ethics, Saint Louis University

Kevin Glauber Ahern, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Religious Studies and Director of Peace Studies, Manhattan College

Ilsup Ahn, Ph.D., Professor of Philosophy, North Park University

Andy Alexis-Baker, Ph.D., Lecturer in Theology, Arrupe College of Loyola University Chicago

Mark J. Allman, Ph.D., Professor of Religious and Theological Studies, Merrimack College

Barbara Hilkert Andolsen, Ph.D., Professor of Christian Ethics, Fordham University

Matthew Ashley, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Systematic Theology, University of Notre Dame

Christina A. Astorga, Ph.D., Professor of Theology and Department Chair, University of Portland

Lauren Murphy Baker, MA, Ph.D. Candidate and Teaching Assistant, Alber Gnaegi Center for Healthcare Ethics, St. Louis University

James P. Bailey, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, Duquesne University

Justin Barringer, Ph.D. Student in Religious Ethics, Southern Methodist University

Jana Marguerite Bennett, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theological Ethics, University of Dayton

Gerald Beyer, Ph.D, Associate Professor, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, Villanova University

Sr. Mary Kate Birge, SSJ, PhD, Fr. Forker Chair of Catholic Social Teaching, Mount St. Mary’s University

Jeffrey Bishop, M.D., Ph.D., Tenet Endowed Chair of Health Care Ethics and Professor of Philosophy, Saint Louis University

Nathaniel Blanton Hibner, , MTS, Ph.D., Candidate, St. Louis University

Kent Blevins, Ph.D. Professor of Religion, Gardner-Webb University

Elizabeth Block, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Christian Ethics, Saint Louis University

Elizabeth M. Bounds, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Christian Ethics, Candler School of Theology and Graduate Division of Religion

Luke Bretherton, Ph.D., Professor of Theological Ethics & Senior Fellow, Kenan Institute for Ethics, Duke University

James T. Bretzke SJ, Professor of Moral Theology, Boston College School of Theology & Ministry

Mikael Broadway, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology and Ethics, Shaw University Divinity School

Shaun C. Brown, Ph.D. Candidate in Theological Studies, Wycliffe College, University of Toronto

Sarah Morice Brubaker, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Theology, Phillips Theological Seminary

Scott Bullard, Ph.D., Senior Vice-President and Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Judson College

Bradley B. Burroughs, Ph.D., Fully Affiliated Faculty in Ethics and Theology, United Theological Seminary

Stina Busman Jost, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology and Ethics, Bethel University

Ken Butigan, Ph.D., Senior Lecturer – Peace, Justice, and Conflict Studies; Affiliate Faculty – Catholic Studies, DePaul University

Jonathan Cahill, Ph.D. Candidate – Theological Ethics, Boston College

Lisa Sowle Cahill, Ph.D., Monan Professor of Theology, Boston College

Charles Camosy, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theological and Social Ethics, Fordham University

Lee Camp, Ph.D, Professor of Theology and Ethic, Lipscomb University

Victor Carmona, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Theology and Religious Studies, University of San Diego

Kevin Carnahan, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religion, Central Methodist University

Colleen Mary Carpenter, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Theology; Carondelet Scholar, Saint Catherine University

Rev. Dr. Christopher Carter, Assistant Professor of Theology and Religious Studies at the University of San Diego, Commissioned Elder of the United Methodist Church

Shaun Casey, Th.D., Professor of the Practice of Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University; Director – Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, Georgetown University; former Special Representative for Religion and Global Affairs, U.S. Department of State

Hoon Choi, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Bellarmine University

Ki Joo (KC) Choi, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Seton Hall University

Drew Christiansen, S. J., Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of Ethics and Global Human Development, Georgetown University, and Senior Research Fellow, the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs

Dolores Christie, Ph.D., Catholic Theological Society of America – Executive Director (Retired)

David Clairmont, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Comparative Religious Ethics, University of Notre Dame

Meghan Clark, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Moral Theology, St. John’s University

Forest Clingerman, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Religion and Philosophy, Ohio Northern University

David Cloutier, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, The Catholic University of America

Elizabeth Agnew Cochran, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, Duquesne University

Dan Cosacchi, Ph.D, Canisius Fellow and Lecturer of Religious Studies, Fairfield University

Richard D. Crane, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Theology, Messiah College

John Crowley-Buck, Ph.D., Adjunct Instructor; Loyola University Chicago

Paul G. Crowley, SJ, Jesuit Community Professor of Theology, Santa Clara University; Fellow – Markkula Center for Applied Ethics; Editor Theological Studies