#portinari triptych

Text

the right door of the Portinari Triptych, painted by Hugo van der Goes 1475-1478

#hugo van der goes#portinari triptych#portinari altarpiece#tommaso portinari#flemish painting#flemish art#netherlandish art#15th century art#oil painting#art history#saint margaret of antioch#mary magdalene#donor portrait#catholic art#catholicism

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

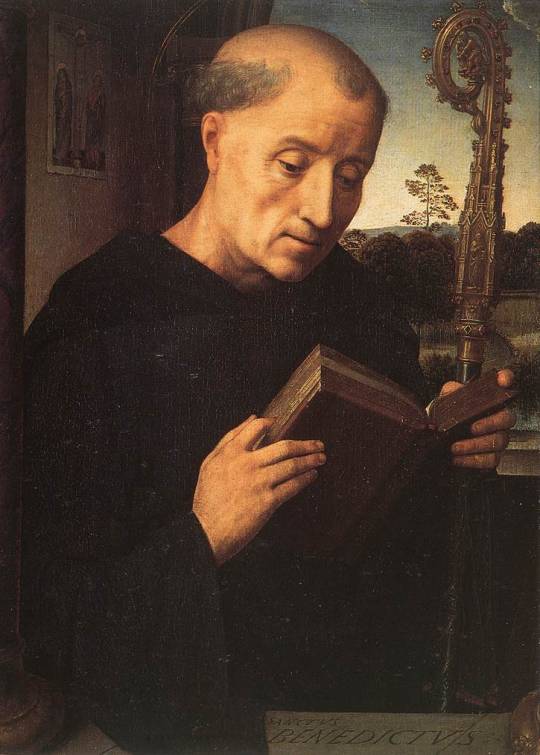

Hans Memling

Tommaso di Folco Portinari (1428–1501); Maria Portinari (Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, born 1456)

Oil on wood, ca. 1470

Image at bottom: Hypothetical reconstruction of the portraits of Tommaso and Maria Portinari with Hans Memling, "Virgin and Child," ca. 1470, oil on oak, (National Gallery, London).

A native of Florence, Tommaso Portinari was the branch manager of the Medici bank in Bruges. He probably commissioned these portraits from Memling around the time of his marriage to the fourteen-year-old Maria Baroncelli in 1470. The two panels originally formed a triptych with a central devotional image of the Virgin and Child.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Virgin of the Annunciation, from the Portinari Triptych, c.1479 (oil on panel)

Hugo van der Goes

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portinari Triptych (left wing). Hans Memling (c.1430-1494)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

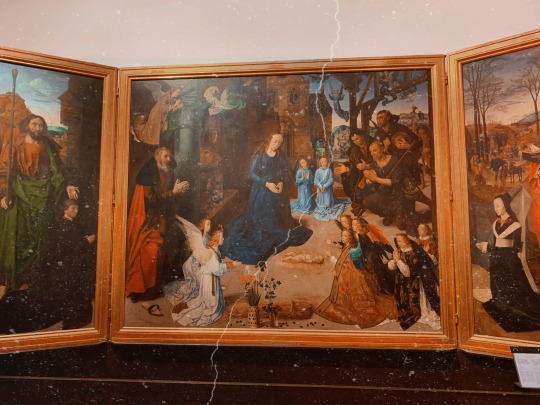

Hugo van der Goes (1440-1482) - Adoration of the Shepherds with Angels and St. Thomas, St. Anthony the Abbot, St Margaret, St. Mary Magdalene and the Portinari family; Annunciation (on the back) c. 1476-1478, Oil on wood

Painted for Tommaso Portinari (1432-1501), the director of the Medici bank's Bruges branch, the side panels of this triptych contain his portrait and those of his wife Maria Baroncelli and their three children, while a monochrome Annunciation is on the back. The picture originally graced the altar in the Church of Sant'Egidio attached to the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which had been founded by the Portinari family. It arrived in Florence in 1483, having traveled a large part of the way by sea.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Portinari Triptych, Hugo van der Goes

c. 1475

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portinari Altarpiece Triptych (Hugo Van Der Goes, 1475-1476 CE).

(via Wikipedia)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Elise Ansel at Danese Corey Gallery

Comparing Elise Ansel’s remake of Northern Renaissance master Hugo van der Goes’ Portinari altarpiece with the original isn’t the point. Ansel distills the main characters from the 15th century Adoration and enlivens them with a dynamic quality that doesn’t exist in the still and measured quality of the original, positing that color, not extreme detail carries the emotion of the scene. (At Danese Corey Gallery through March 11th). Elise Ansel, Portinari Triptych, oil on linen, 60 x 144 (overall), 2016.

#elise ansel#portinari triptych#painting#painter#influence#remake#abstract#hugo van der goes#danese corey gallery#art#artist#gallery#tour#art tour#gallery tour#chelsea#chelsea tour#chelsea galleries

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

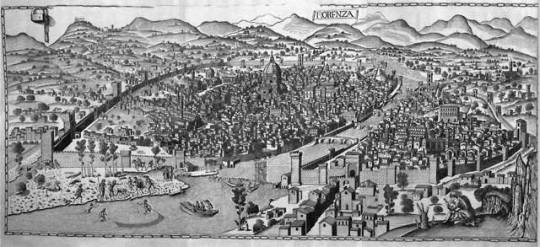

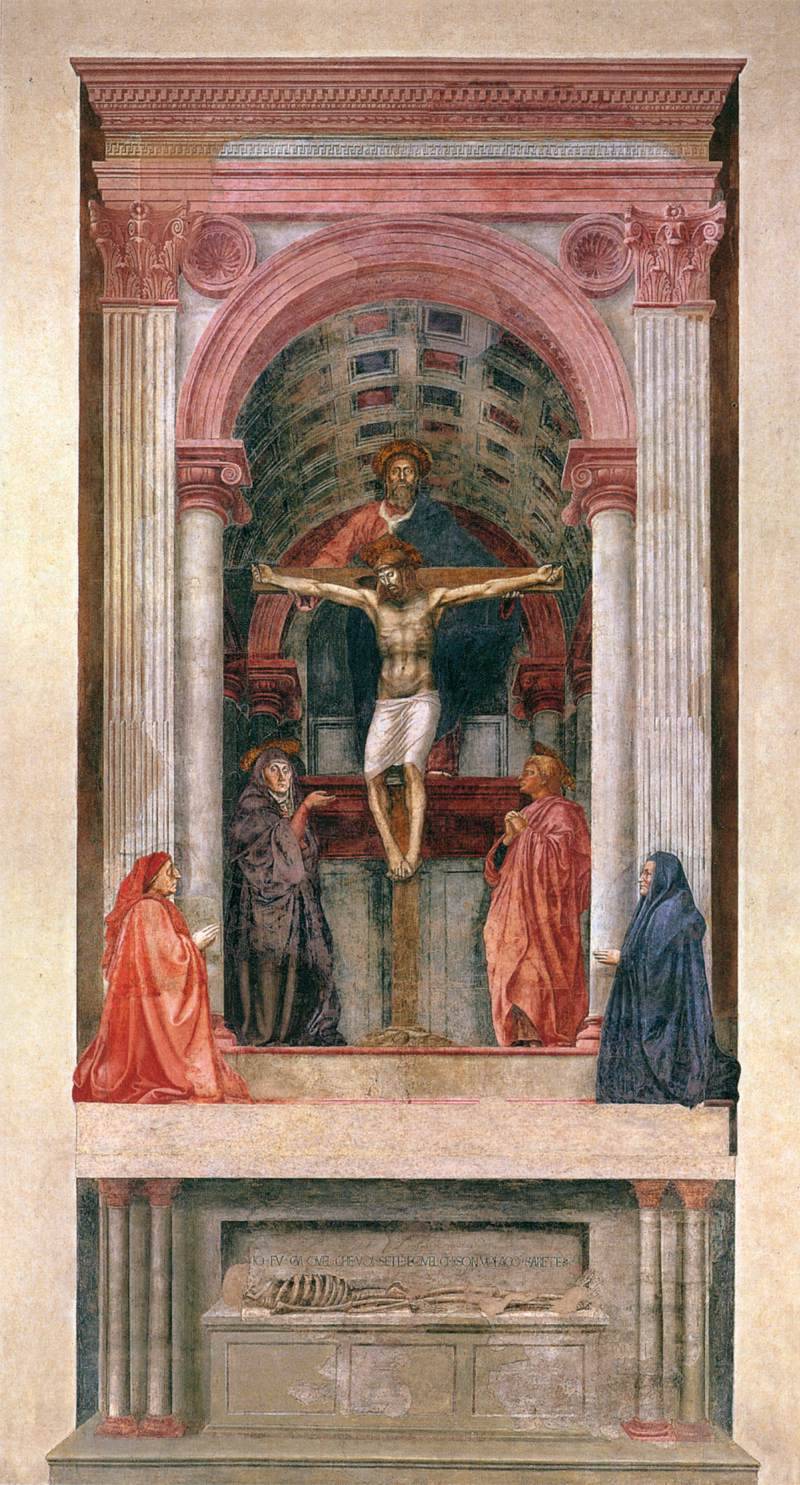

The Portinari Altarpiece: Cultural Dialogue between North and South

Tommaso Portinari (1428-1501) was an agent of the Medici family in Bruges, where he headed a branch of the Medici bank. Tommaso was known for his interest in Northern Art, no doubt cultivated during the time he spent in Bruges, and had his and his wife’s portrait painted by Hans Memling in an extraordinarily realistic manner. Among Tommaso’s most notable contributions to Italian culture, however, is the Portinari Altarpiece, a monumental achievement by Netherlandish painter Hugo van der Goes (c.1440-1482). This triptych, though completed in the Dutch style, aligned with Florentine tastes for grandiose commissions; it is one of the largest Netherlandish paintings of the 15th century.

The triptych was intended for the altar of Sant’ Egidio in Florence, the Portinari family church, where it was held for a time. Today it is housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The scene is dominated by the theme of the Adoration of the Magi which appears in the central panel. In many ways, the painting fuses Northern elements with those of Florentine Renaissance art. As was customary in private patronage in Florence, the donors are depicted on either side of the central scene, a practice which can also be observed in Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Tornabuoni Chapel frescoes and Masaccio’s Trinity, both in Santa Maria Novella, Florence. However, the abundant, angular folds of the drapery and the slightly skewed perspective, not to mention the unflattering realism, of van der Goes painting speaks more to a Northern approach to painting.

When the triptych arrived in Florence on 28th May 1483 it caused quite a sensation amongst artists and critics. With the vogue of Albertian naturalism, the striking realism achieved by van der Goes’ use of oil paint (a relatively unused medium in Florence at the time) piqued the interest of artists whose goal it was to create a ‘window onto the world’. Further, the lack of idealisation of the Virgin, Christ, and especially of the shepherds represented a notable departure from contemporary practices observed when executing sacred scenes. The triptych had a notable influence on manuscript illumination, and especially on Umbrian painters such as Luca Signorelli.

Reference: Dirk de Vos, The Flemish Primitives: The Masterpieces, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, 1476-79, oil on wood, Uffizi, Florence.

Hans Memling, Portrait of Tommaso Portinari and his Wife Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, c.1470, oil on wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Francesco Roselli, View of Florence with the Chain, 1480s, woodcut, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence.

Masaccio, Trinity, c.1425, fresco, Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portraits of Giovanni Tornabuoni and Francesca Pitti-Tornabuoni, 1486-90, fresco, Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

(Images: Web Gallery of Art)

Further Reading: Susanne Franke, "Between Status and Spiritual Salvation: The Portinari Triptych and Tommaso Portinari's Concern for His Memoria." Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 33, no. 3 (2007): 123-44.

Posted by: Matthew Whyte

#northern art#renaissance art#renaissance florence#hugo van der goes#oil painting#triptych#altarpiece#portinari#art history#flemish primitives

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portinari Triptych (central panel), 1487, Hans Memling

Medium: oil,wood

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, oil on wood, 274 x 652 cm when open (Uffizi)

Hugo van der Goes, Portinari Altarpiece

Created by Smarthistory.

By Dr. Rebecca Howard

Artworks are powerful things. Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece caused quite a stir when it arrived in Florence—the city that was to become its permanent home. Van der Goes, master of light and minute descriptive details, is considered one of the greatest Netherlandish painters of the second half of the fifteenth century. The Portinari Altarpiece is a large triptych

that was commissioned by an Italian named Tommaso Portinari, who was living in the Netherlands.

An Italian family in the North

Just as today, people in the renaissance often traveled extensively or even moved permanently for work. Portinari, his wife Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, and their children were living in Bruges at the time of this painting’s creation. Tommaso worked as a high-ranking agent of the Medici banking industry, helping to run a branch of the bank in Bruges. The Medici were one of the most powerful families in western Europe, and their lineage had developed an extremely wealthy banking, mercantile, and political family. Agents throughout Europe managed branches of their banking empire.

The Portinari family and Florence’s Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova

While Tommaso had made a name for himself in Bruges, his family remained important to the history of Florence. In 1288, Tommaso’s ancestor, Folco Portinari, founded the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, today the oldest functioning hospital in Florence. In the 1420s, the Portinari family supported further renovations to the hospital, which, by the fifteenth century had around 200 beds (up from 12). As with many hospitals today, Santa Maria Nuova had a connected church, Sant’Egidio.

The Portinari Altarpiece was commissioned for the main altar of this church, and was simultaneously a way for Tommaso to perpetuate his family’s name and importance in conjunction with the city of Florence and the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova.

The Portinari Altarpiece stands as a highlight of Tommaso’s career and the public image he hoped for his family name to retain. Unfortunately, the Portinari family fell on difficult financial times not long after this painting’s creation, as Tommaso lost the Medici family a great deal of money through loans to Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, which were never paid back in full.

Hugo van der Goes and north-south exchange

Portinari’s choice of a Netherlandish artist to complete this great altarpiece to be sent back to Florence helped to effectively change aspects of Italian art. The latter half of the fifteenth century was characterized by increased artistic exchange between northern European and Italian artists. Italian artists were enthralled by Northern artists’ careful attention to individual details and still-life minutiae incorporated in architectural settings and landscapes. Hugo van der Goes was considered a master of such careful, minute details and his talent was often compared to that of Jan van Eyck, considered one of the greatest painters of the early fifteenth century. Look closely, for example, at van der Goes’s rendering of the foreground angels’ garments. It appears as though we can physically touch the gold brocade of the fabric. And the clear vessel in the foreground also flawlessly seems to capture, reflect, and refract light.

Such tiny details are found throughout the Portinari Altarpiece, and nearly all of them hold some iconographic meaning. When this painting finally arrived in Florence in 1483 for its installation in the church of Sant’Egidio, it had a direct, visible effect on artistic production in Italy. A particularly famous painting that clearly recalls the Portinari Altarpiece is Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Adoration of the Shepherds, painted in 1485—only two years after the Portinari Altarpiece arrived in Florence. In Ghirlandaio’s painting, one can see that the shepherds adoring the Christ child are rendered with such individualized detail that they feel like portraits, as in the Portinari Altarpiece. The group also takes the exact same formation as the three shepherds pictured in van der Goes’s work.

Layered iconography

Iconography, commonly used in the field of art history, is the study of the symbolic meaning of things found in works of art. In northern renaissance art, artists frequently used certain figures, objects, and even depictions of biblical or historical events to symbolize something more to period viewers than what was seen on the surface. The iconography throughout the Portinari Altarpiece is extensive and quite complex.

Triptych altarpieces like the Portinari Altarpiece would have been kept closed, except on holidays and special feast days. Therefore, the exterior of the folding side wings of such artworks were typically painted. The Portinari Altarpiece’s exterior is decorated with a depiction of the Annunciation, the biblical event when the Angel Gabriel appeared to the Virgin Mary to tell her that she had been chosen to carry the son of God. This moment is understood in the Christian faith as the beginning of mankind’s salvation. Here, we see it essentially frozen in time, as the artist has chosen to paint these figures in grisaille. These faux sculptural figures are located in shallow architectural niches and reveal van der Goes’s incredible artistic talent in their believable naturalism.

Upon seeing the Portinari Altarpiece opened, one can imagine that any period viewer would have been stunned by the elaborate details and bright colors contained on the three panels within. In the center panel, we are privy to the quiet, magical moment just after Christ’s birth, the Nativity. Angels surround the kneeling Virgin Mary and newborn Christ child, and the three shepherds have rushed in from the countryside to bear witness to the miracle. This scene would have been instantly recognizable to any period viewer, and most would have noticed the iconographic details—certain objects and scenes that held multiple meanings.

Far in the distance, behind the heads of the shepherds, we see those very same shepherds attending to their flock on the hillside. These tiny figures make gestures of surprise as an angel appears above them. This is the moment of the Annunciation of the Shepherds, when they were told that Christ had been born. In the repetition of these shepherds in the background and again in the foreground, the artist has used what is called continuous narrative, wherein figures are repeated within the same frame of an artwork to show more than one moment of a story.

In the center are the most important figures in the scene, the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ. It may seem strange that Christ is laying naked on the bare, hard ground, and that rays of light appear to emit directly from his body. However, this imagery is drawn from the writings of a medieval visionary named St. Bridget of Sweden. By the fifteenth century St. Bridget’s vision of the Nativity had become the inspiration for many depictions of this moment. Mary kneels beside Christ on the ground, a position meant to emphasize her humility, and bends over in somber adoration of her child. And her solemn nature, in this case, is meant to foretell what is to come—that she will have to sacrifice her son for the salvation of humanity.Perhaps the most striking detail in the central panel is the group of objects in the foreground. Imagine this altarpiece in its original location, just above the altar of Sant’Egidio. The two vases would appear almost as though they were sitting on the altar itself. Notice, too, that the sheaf of wheat behind them is quite similar in color to and situated directly parallel with Christ’s body. At Mass, a priest would consecrate the Eucharist—the bread and wine—thereby turning it into the body and blood of Christ (according to Catholic tradition), which would be consumed in remembrance of his sacrifice. The hem of the red and gold brocaded vestment worn by the angel foregrounded on the right is embroidered with the repeated word “sanctus,” or holy, referencing the moment of the consecration of the Eucharist. The positioning of Christ’s body parallel to the sheaf of wheat, which in turn would be parallel to the physical bread on the altar, functioned as a stark reminder of what really took place at communion. The image masterfully creates a visual equation between the bread, the wheat, and Christ’s body.

The vases and flowers just in front of the wheat are carefully studied depictions of recognizable flowers that each held symbolic meaning for period viewers. The Spanish albarello vase on the left is a type of vessel that traditionally held herbs and ointments used by apothecaries, an artistic choice which was almost certainly meant to comment on the altarpiece’s location in a hospital’s church. The albarello vase holds two white and one purple iris, along with a scarlet lily. These flowers represent the purity (white), royalty (purple), and Passion, or tortures, (red) of Christ. This vessel is also decorated with an ivy leaf motif that resembles a grape vine, alluding to wine, and therefore, to the blood of Christ, consumed with His body during Mass. The presence of this vase also reminds us that Valencia (in Spain), Italy, and northern Europe were engaged in extensive trade during this time, and expanding their trade across the globe. Spanish lusterware, like this vase, was a popular luxury trade item in the fifteenth century, admired for its reflective surface. The luster technique derives from Islamic pottery, and it is important to keep in mind that the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) had a large Muslim population.

The clear vessel to the right holds three red carnations and seven blue columbines. The seven columbines are symbolic of the Seven Sorrows of Mary, while the three red carnations make reference to the three bloodied nails at Christ’s Crucifixion. As you can see, many of these flowers were meant to remind viewers of what was to come for Christ.The story grows, and so does the Portinari family

Having discussed the details of the central panel, let’s take a look at the two side panels. In the backgrounds of each of the side panels, we find scenes that occurred before, after, and during the primary scene of the Nativity in the center. And just as the story is expanded in the side panels, we see that Tommaso and Maria have expanded their lineage, as well. Van der Goes, a master of detailed portraiture, depicted Tommaso Portinari in the left panel, kneeling in prayer as he faces the miraculous scene in the center. Because he paid for this elaborate gift, his family’s inclusion in the altarpiece essentially guarantees that they will forever be included in the daily prayers carried out in the church. Tommaso is accompanied by their two sons (as of the creation of this painting c. 1476), Antonio and Pigello, who kneel behind him. Note that, even if Tommaso were standing, he would still be noticeably smaller than the two figures who stand behind him. This is known as hierarchy of scale, where a visible difference in size between figures indicates that larger figures are of higher status. In this case, the larger figures are saints. St. Thomas, the name saint of Tommaso, works as his intercessor, effectively “introducing” him to the scene in the center and helping to convey his prayers to heaven. Behind St. Thomas is St. Anthony, the name saint of Antonio, as well as a “plague saint” who was frequently invoked by the sick, suffering, and dying. His presence makes yet another connection to the altarpiece’s original hospital location.

In the right panel, Maria Maddalena Baroncelli kneels in a position that mirrors her husband’s, accompanied by their daughter Margarita. These two figures are joined by their name saints, Mary Magdalene and St. Margaret. Interestingly, however, it is St. Margaret who stands behind Maria, not her name saint Mary Magdalene. St. Margaret is the patron saint of childbirth, and is evoked by pregnant women and those in labor in hopes of a successful process and outcome. St. Margaret is typically depicted as emerging from the mouth of or standing atop a dragon, as seen here (her legend explains that she survived being consumed by Satan, disguised as a dragon, whose stomach then rejected her and she emerged unharmed). As such, it is speculated that this may have been a deliberate choice, as Maria’s primary role as a wife in the fifteenth century was to bear children and continue the Portinari lineage, so she felt a stronger connection to St. Margaret at this point in her life.

Just as in the central panel, the side panels also include small scenes in the background. In fact, the left panel continues the theme of childbirth already indicated by the Nativity in the center and the presence of St. Margaret in the right panel. Far in the distance behind St. Anthony’s head, we see Joseph attending to a pregnant Virgin Mary who has decided to walk rather than ride her donkey. This is a precursor to the miraculous birth that will soon occur, the Nativity. In the right panel, the landscape is populated by scenes of the three kings, the Magi, on their journey from far parts of the world to visit the newborn Christ.

What the northern painters did best

Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece encompasses the numerous aspects of northern renaissance painting that enthralled those in other parts of the world. This particular artwork perfectly embodies all the things that northern European painters were thought to do best—the rendering of complex landscapes that stretch far into the distance, skies that seem to capture light at different times of the day or under different circumstances, faces that appear highly individualized, even when they are not intended to be recognizable portraits, and carefully rendered, incredibly minute details throughout. Considering this triumph of artistic virtuosity, along with the work’s fascinating layers of symbolism, the direct and immediate impact of the Portinari Altarpiece on the art world of late-fifteenth-century Florence comes as no surprise. It is after this moment that we see, in particular, increased individualism in Italian faces and, perhaps even more importantly, a swift rise in the use of oil paint in Italian city-states.

Read about this painting on the Uffizi website

https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/adoration-of-the-shepherds-with-angels-and-saint-thomas-saint-anthony-saint-margaret-mary-magdalen-and-the-portinari-family-recto-annunciation-verso

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/northern-renaissance1/xa6688040:hugo-van-der-goes/a/hugo-van-der-goes-portinari-altarpiece

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

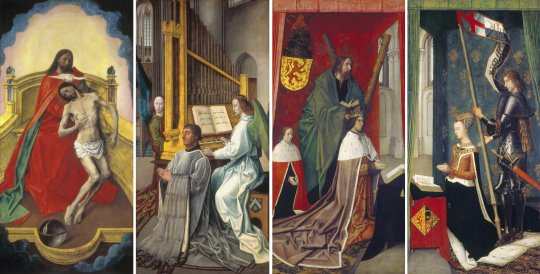

Historical Objects: The Trinity Altarpiece

(Click image for better view. Inside panels are on the right, outside on left. Source- wikimedia commons)

The Trinity Altarpiece is one of the most remarkable objects to have survived from mediaeval Scotland. Produced by Hugo van der Goes in the 1470s, this triptych would have occupied pride of place on the high altar of Trinity Collegiate Kirk in Edinburgh. Though the centre panel is now lost, the wings survive including depictions of the Holy Trinity, angels and saints. Perhaps of more interest are the contemporary historical figures depicted: on the outside of the left-hand panel is pictured the provost of Trinity kirk, Edward Bonkil; on the inside left-hand panel King James III (r.1460-1488), accompanied by a boy who may be the future James IV; and on the inside right-hand panel James III’s queen Margaret of Denmark. A precious survival from a country where only a small percentage of mediaeval art survived the iconoclasm of the Reformation, and centuries of Anglo-Scottish, religious, and civil wars, the Trinity Altarpiece gives a rare glimpse into the vibrant cultural networks of a small European kingdom and the interests of its elites.

This impressive piece was probably created by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes, who was born in the mid-fifteenth century in the great city of Ghent, then a major European centre. Goes was first mentioned in 1467, the same year he was admitted to the painters’ guild of Ghent. Over the next decade he frequently undertook painting work (both practical and artistic) in Ghent and further afield. He served as both juror and dean of the painters’ guild during the mid-1470s, but by 1478 had retired to the Roode Klooster near Brussels, where he lived for the rest of his life. In later years one of his fellow novices at the Roode Klooster, Gaspar Ofhuys, wrote an account of Goes’ time there, which provides a valuable insight into his life and character. Goes often received visitors, including Maximilian, Archduke of Austria and other notable figures. He was also occasionally allowed to leave the monastery to undertake commissions and travel to some of the region’s cities. While returning from one such trip to Cologne, however, he suffered a fit of madness and attempted suicide. He briefly recovered only to die shortly afterwards, in 1482, tormented towards the end of his life by the thought of not finishing his art. Nevertheless he is now recognised as one of the most significant and talented Flemish painters of his time, despite his short career- and the difficulty of identifying his work.

Most identifications of Hugo van der Goes’ paintings rest on similarities with the Portinari Altarpiece, the only work confidently attributed to him. Thus many of his purported works- which include the ‘Lamentation of Christ’ (now in Vienna), the ‘Adoration of the Kings’ (or the Monforte Altarpiece, now in Berlin), and others which only survive in copies made by his followers- cannot be certainly attributed, though as yet there is no real reason to doubt the Trinity Altarpiece. In any case the Trinity panels are clearly of the highest quality and represent an important contribution to Northern Renaissance art. Moreover, their existence sheds light on the networks of artistic patronage in mediaeval Europe and the links of one particular Scottish churchman and his royal patrons.

(The Portinari Altarpiece, also by Hugo van der Goes. The centre panel flanked by the inside of two wings gives some idea of how the Trinity Altarpiece would have looked when open, before the centre panel was lost. Source Wikimedia Commons)

While they are now appreciated primarily for their artistic value, these mediaeval altarpieces also had a practical purpose. As portable religious items they helped direct the spiritual devotions of their owners, while they also had worldly usefulness, prominently displaying the patron’s political, spiritual, and social networks. In triptychs, patrons and their family members were usually represented on the inside wings, like the royal figures in the Trinity Altarpiece. Here the king and queen of Scots- James III and Margaret of Denmark- are portrayed in rich costume, accompanied by Saints Andrew and George, and a young boy who probably represents their eldest son, James, Duke of Rothesay. Despite the prominence of the royal family however, the Altarpiece may owe its origin to a very different individual. When a triptych was not in use, the inner wings would usually close over a larger centre panel (the Trinity Altarpiece’s appears to have been lost) and the outside panels were often decorated with less showy ‘grisaille’ paintings. In the Trinity Altarpiece, however, these outer panels tell us even more about the work’s provenance. Portrayed on the left outer wing is the Holy Trinity (father, son, and holy spirit) and, on the right wing, kneeling in supplication before the Trinity, a churchman whose coat of arms identifies him as Edward Bonkil, first provost of Trinity Collegiate Church in Edinburgh- the man who probably commissioned this expensive work of art.

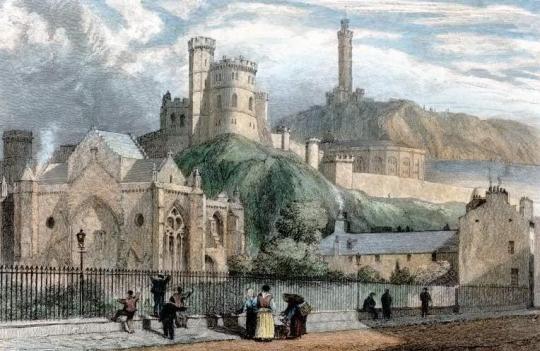

Trinity College Kirk, which stood beneath Calton Hill, was founded in 1460 as the pet project of Mary of Guelders, queen consort to James II of Scotland (1437-1460). Mary was not just the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders but also the great-niece of Philip the Good, the powerful Duke of Burgundy, and as Mary was raised at her uncle’s court her marriage to James II strengthened Scotland’s traditional commercial and cultural ties with the Low Countries. A formidable woman, Mary headed the government after her husband’s premature death in 1460, as regent for her young son James III. She also had some reputation as a builder (her other major project was Ravenscraig Castle, the first castle in Scotland built specifically to withstand artillery fire, and she contributed to works elsewhere too). Though work on the church may have begun in her husband’s lifetime, it was chiefly Mary’s project and from 1460 onwards she took a keen interest in the foundation. Besides paying for its endowment and construction, she may have personally contributed to the creation of the college rules, stipulating that all the canons and boys should be capable of reading and singing in plain chant and descant, laying the foundations of Trinity’s reputation as a prestigious choral institution. Following her early death in 1463, she was also buried in the church, probably near the high altar, where the altarpiece likely stood and it has been theorised that the missing middle panel could have included a representation of the queen dowager herself, drawing attention to the church’s royal associations. However the altarpiece was painted after her death, and indeed the responsibility for commissioning this costly piece of art may not have lain with the royal family at all, although Mary’s son James III and his queen feature prominently on its inner panels. It has been argued by Lorne Campbell that we should instead look to the provost of Trinity, Edward Bonkil, portrayed on the right-hand outer panel of the altarpiece.

(Bottom left- Trinity College Kirk, as it appeared in the nineteenth century. Source- Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Bonkil had been a close servant of the late Mary of Guelders, having been personally promoted to the position of provost of her lavish foundation. After the dowager’s death, however, he seems to have gradually fallen out of favour at court and it is suggested by Campbell that he may have commissioned the altarpiece partly with a view to currying favour with the young James III. Whether this is accurate or not, it seems highly probable that Bonkil was the main driving force behind the commission- not only does he occupy a privileged position on the outer wing of the altarpiece, but his features are much more detailed and exact than those of the royal family, suggesting that they were painted from life. As a member of a prominent Edinburgh merchant family, and having possibly served on embassies to Guelders and Burgundy, Bonkil had close connections with the Low Countries. Moreover he is not recorded in Scotland between 1473 and 1476, around the time that the altarpiece may have been painted, and so he could have travelled to Flanders personally to sit for the artist. Though it did not bring him renewed royal favour, if the altarpiece was commissioned by Bonkil it not only secured his legacy but has provided us with a rare and invaluable glimpse into the tastes and cultural connections of late mediaeval Scotland’s clerical elite.

Much of the altarpiece, including the likeness of Bonkil, is believed to have been painted in Flanders by Goes, and certain sections are even adapted from other works by Flemish artists, such as the ‘Madonna in the Church’ by Jan Van Eyck, which forms the backdrop to Bonkil’s panel, and a lost work by Robert Campin which influenced the representation of the Trinity. The faces of King James III and Queen Margaret however, may have been painted over by an unknown artist upon the altarpiece’s arrival in Scotland, to lend them some realism, though they are not of such high quality as the depiction of Bonkil. The portrayal of the young Duke of Rothesay- the future James IV- is probably even less true to life, as portrayals of children in late mediaeval art were more often symbolic than realistic and it is probable that Rothesay was an infant at most at the time of the painting’s creation. His appearance may allow us to tentatively date the work however, as he was born in 1473 and described as James III’s ‘only son’ until 1478-9, and neither of his younger brothers are portrayed in the painting. This place the period of production in the mid-1470s- a rare survival then, from an otherwise shadowy period in late mediaeval Scottish history.

(Edward Bonkil, Provost of Trinity Collegiate Church, who probably commissioned the altarpiece. Source- wikimedia commons)

Despite having been painted almost a century and a half earlier however, the panels from the Trinity Altarpiece were only recorded in written sources for the first time in 1617, when they were included in an inventory taken of the possessions of Anne of Denmark, queen of James VI of Scotland (James III’s great-great grandson and by now James I of England also). The inventory of Queen Anne’s belongings was taken at the royal residence of Oatlands in Surrey, and it has been suggested that the Trinity Altarpiece was brought south after her husband’s last visit to Scotland earlier in 1617. It was to remain in England for many years thereafter, passing into the hands of Anne’s son, Charles I, by 1624, when it was erroneously described as a work by Jan van Eyck. The altarpiece was auctioned off during the Civil War but was reclaimed by the royal family after the Restoration, after which it was displayed in various English royal palaces, including Kensington and Hampton Court. In 1857, it returned to Scotland for the first time in over two hundred years when it was briefly transferred to Holyrood Palace during the reign of Queen Victoria. Over the next few decades it was shuffled around on several occasions, but was often on public display at Holyrood until 1912, when it was first briefly loaned to the National Gallery of Scotland, due to fears over its safety in the face of militant suffragette activity. In 1931, it again returned to the National Gallery, in whose care it remains today.

If anyone has a spare half an hour in Edinburgh some day, I highly recommend visiting the galleries, if only to see the Altarpiece. Flemish art of this period is both fascinating and beautiful and the Galleries are very fortunate to own a piece of such high calibre as the Trinity Altarpiece. As well as this, the culture of mediaeval Scotland has left few traces in the modern day: even the impressive Trinity Collegiate Church, the original home of the altarpiece, was largely demolished in the Victorian period to make way for Waverley Station, while many other pieces of art, books, buildings, music and historical sources have been lost to the ravages of war, iconoclasm, and time. The survival of such a beautiful and costly work as the Trinity Altarpiece, therefore, stands testament to a fascinating and complex past, as culturally vibrant as that of any other corner of mediaeval Europe, and just waiting to be uncovered.

(Source - Wikimedia commons)

Selected Bibliography:

“Charters and documents relating to the Collegiate Church and Hospital of the Holy Trinity, and the Trinity Hospital, Edinburgh, A.D. 1460-1661″, ed. J.D. Marwick

“Rotuli scaccarii regum Scotorum: the Exchequer Rolls of Scoltand”, eds. John Stuart and George Burnett, volumes 6, 7, & 8

“Hugo van der Goes and the Trinity Panels in Edinburgh”, C. Thompson and L. Campbell

“Hugo van der Goes’s Altarpiece for Trinity College in Edinburgh and Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scotland”, T. Tolley

“She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland, 1424-1463″, Fiona Downie

National Galleries of Scotland

#Scottish history#art history#early Netherlandish#Northern Renaissance#Flemish history#Flanders#the Low Countries#Hugo van der Goes#Edward Bonkil#Mary of Guelders#James III#Margaret of Denmark#art#historical objects#culture#fifteenth century#late middle ages#Trinity Collegiate Church#Holy Trinity#Edinburgh#Ghent#painting#James IV#Scotland and the World#religion#kirk and people#National Gallery of Scotland#Christianity#the Stewarts#Living in Medieval Scotland

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Last Judgment – Hans Memling The Last Judgment is a triptych attributed to Flemish painter Hans Memling and painted between 1467 and 1471. It is now in the National Museum in Gdańsk in Poland. It was commissioned by Angelo Tani, an agent of the Medici at Bruges, but was captured at sea by Paul Beneke, a privateer from Danzig. (A lengthy lawsuit against the Hanseatic League demanded its return to Italy.) It was placed in the Basilica of the Assumption but in the 20th century it was moved to its present location. The triptych depicts the Last Judgement during the second coming of Jesus Christ, the central panel showing Jesus sitting in judgment on the world, while St Michael the Archangel is weighing souls and driving the damned towards Hell (the sinner in St. Michael’s right-hand scale pan is a donor portrait of Tommaso Portinari); the left hand panel showing the saved being guided into heaven by St Peter and the angels; and the right-hand panel showing the damned being dragged to Hell. #HansMemling https://www.instagram.com/p/B9sEw-Ygwqe/?igshid=1oka869vyyv2t

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Portinari Triptych (central panel), 1487, Hans Memling

Size: 31x43 cm

Medium: oil, wood

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portinari Triptych (central panel). Hans Memling (c.1430-1494)

0 notes

Text

Alighieri Dante (c. 1265–1321) La Divina Commedia Inferno Canto V. I. 1-15 Minos who judges the second circumference, 13-15., 15. Dicono e odono e poi son giù volte. (Says and hears and then below times.), Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444), Mérode Altarpiece, ca. 1427–32, The Metropolitan Museum of Art., Hugo van der Goes (Flemish, c. 1430/1440–1482), The Monforte Altarpiece, c.1470, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Hugo van der Goes 31.03.2023 bis 16.07.2023 Gemäldegalerie, The Portinari Altarpiece, 1475-76, Uffizi Gallery., Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, baptised 1684-1721), Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère, 1717, Louvre., Pilgrimage to Cythera, c. 1718–1719, L'Enseigne de Gersaint, c. 1720–1721, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin., Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, OM, RA (Dutch, 1836–1912), The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888

Alighieri Dante (c. 1265–1321) La Divina Commedia Inferno Canto V. I. 1-15 Minos who judges the second circumference, 13-15., 15. Dicono e odono e poi son giù volte. (Says and hears and then below times.), Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444), Mérode Altarpiece, ca. 1427–32, The Metropolitan Museum of Art., Hugo van der Goes (Flemish, c. 1430/1440–1482), The Monforte Altarpiece, c.1470, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Hugo van der Goes 31.03.2023 bis 16.07.2023 Gemäldegalerie, The Portinari Altarpiece, 1475-76, Uffizi Gallery., Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, baptised 1684-1721), Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère, 1717, Louvre., Pilgrimage to Cythera, c. 1718–1719, L'Enseigne de Gersaint, c. 1720–1721, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin., Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, OM, RA (Dutch, 1836–1912), The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888

https://blog.naver.com/artnouveau19/222653597869

Alighieri Dante (c. 1265–1321)

La Divina Commedia

Inferno

Canto V.

I. 1-15

Minos who judges the second circumference

Sempre dinanzi a lui ne stanno molte: (Always in front of him from there they are a lot.)

Vanno a vicenda ciascuna al giudizio, (Goes in turn everybody to the judgement.)

Dicono e odono e poi son giù volte. (Says and hears and then below times.)

Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, ca. 1375–1444 Tournai), Mérode Altarpiece (Annunciation Triptych), ca. 1427–32, Oil on oak, Dimensions: overall (when open), 25 3/8 × 46 3/8 in.; central panel, 25 1/4 × 24 7/8 in.; each wing, 25 3/8 × 10 3/4 in., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. On view at The Met Cloisters in Gallery 19

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mérode_Altarpiece

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470304

Hugo van der Goes (Flemish, c. 1430/1440–1482), The Monforte Altarpiece (Adoration of the Magi), c.1470, Oil on wood, 147×242cm (58×95in), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monforte_Altarpiece

Hugo van der Goes

31.03.2023 bis 16.07.2023

Gemäldegalerie

Hugo van der Goes (um 1440-1482) war der wichtigste niederländische Künstler der zweiten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts. Tätig in Gent und Brüssel, gehörte er der zweiten Generation altniederländischer Meister an, die den Pionieren Jan van Eyck und Rogier van der Weyden folgte. Seine Werke wurden von den Zeitgenossen aufs Höchste bewundert und bis ins 17. Jahrhundert hinein vielfach kopiert. Noch Albrecht Dürer nennt ihn 1520, wie nur ganz wenige andere Künstler, einen „großen Meister“. Die Gemäldegalerie präsentiert 2023 die erste ihm gewidmete Sonderausstellung.

https://www.smb.museum/ausstellungen/detail/hugo-van-der-goes/

Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440 – 1482) was one of the most significant and original Flemish painters of the late 15th century. Van der Goes was an important painter of altarpieces as well as portraits. He introduced important innovations in painting through his monumental style, use of a specific colour range and individualistic manner of portraiture. From 1483 onwards, the presence of his masterpiece, the Portinari Triptych, in Florence played a role in the development of realism and the use of colour in Italian Renaissance art.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugo_van_der_Goes

Hugo van der Goes (Flemish, c. 1430/1440–1482), The Portinari Altarpiece, 1475-76, Oil on wood, Uffizi Gallery.

https://www.uffizi.it/en/online-exhibitions/portinari-triptych

The Portinari Altarpiece or Portinari Triptych (c. 1475) is an oil on wood triptych painting by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes, commissioned by Tommaso Portinari, representing the Adoration of the Shepherds. It measures 253 x 304 cm, and is now in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Italy. This altarpiece is filled with figures and religious symbols. Of all the late fifteenth century Flemish artworks, this painting is said to be the most studied.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portinari_Altarpiece

Jean-Antoine Watteau (UK: /ˈwɒtoʊ/, US: /wɒˈtoʊ/,[2][3] French: [ʒɑ̃ ɑ̃twan vato]; baptised October 10, 1684 – died July 18, 1721)[4] was a French painter and draughtsman whose brief career spurred the revival of interest in colour and movement, as seen in the tradition of Correggio and Rubens. He revitalized the waning Baroque style, shifting it to the less severe, more naturalistic, less formally classical, Rococo. Watteau is credited with inventing the genre of fêtes galantes, scenes of bucolic and idyllic charm, suffused with a theatrical air. Some of his best known subjects were drawn from the world of Italian comedy and ballet.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_Watteau

Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, baptised 1684-1721), The Embarkation for Cythera ("L'embarquement pour Cythère”, Pèlerinage à l'île de Cythère), 1717, 1.29x1.94m, Louvre. SALLE 917

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061995

The Embarkation for Cythera (Louvre version): Many commentators note that it depicts a departure from the island of Cythera, the birthplace of Venus, thus symbolizing the temporary nature of human happiness.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Embarkation_for_Cythera

Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, baptised 1684-1721), Pilgrimage to Cythera, c. 1718–1719, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_Watteau#/media/File:Antoine_Watteau_-_L'imbarco_per_Citera.jpg

The Embarkation for Cythera ("L'embarquement pour Cythère") is a painting by the French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau. It is also known as Voyage to Cythera and Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera. Watteau submitted this work to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture as his reception piece in 1717.[1] The painting is now in the Louvre in Paris. A second version of the work, sometimes called Pilgrimage to Cythera to distinguish it, was painted by Watteau about 1718 or 1719[2] and is in the Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Embarkation_for_Cythera

Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, baptised 1684-1721), L'Enseigne de Gersaint, c. 1720–1721, Oil on canvas, 163×308cm (64×121in), Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27Enseigne_de_Gersaint

https://www.spsg.de/en/palaces-gardens/object/charlottenburg-palace-old-palace/

L'Enseigne de Gersaint (transl. "The Shop Sign of Gersaint") is an oil on canvas painting in the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, by French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau. Completed during 1720–21,[1] it is considered to be the last prominent work of Watteau, who died some time after. It was painted as a shop sign for the marchand-mercier, or art dealer, Edme François Gersaint.[2] According to Daniel Roche the sign functioned more as an advertisement for the artist than the dealer.[3]

The painting exaggerates the size of Gersaint's cramped boutique, hardly more than a permanent booth with a little backshop, on the medieval Pont Notre-Dame, in the heart of Paris, both creating and following fashion as he purveyed works of art and luxurious trifles to an aristocratic clientele.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, OM, RA (Dutch, 1836–1912), The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, oil on canvas, 132.1×213.7 cm, private collection.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Roses_of_Heliogabalus

0 notes