#Mary of Guelders

Text

↳ Historical Ladies Name: Mary/Marie/Maria

#mary of woodstock#mary of waltham#mary of guelders#mary of burgundy#mary tudor#mary of guise#mary i of england#mary queen of scots#marie de medici#mary princess royal#mary of modena#maria theresa of spain#mary ii of england#maria theresa#marie antoinette#mary of teck#my gifs#creations*#historicalnames*#historyedit#efoor

467 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♕ Queens who served as Regent of Scotland (during part of their child’s minority)

#historyedit#scottish history#medieval history#early modern history#history#house of stewart#kingdom of scotland#joan beaufort#mary of guelders#margaret tudor#queen consorts#qc: joan beaufort#qc: mary of guelders#qc: margaret tudor#qc: marie of guise#k: james ii#k: james iii#k: james v#qr: mary i#ours

322 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Margaret’s and her son’s refuge after the Lancastrian defeat at Northampton was Scotland, where she got a sympathetic hearing from the recently widowed queen, Mary of Guelders, who was acting as regent for her young son James III. Contrary to widely accepted accounts, this is where Margaret was residing at the time of the battle of Wakefield, fought on 30 December 1460. The dramatic scenes presented by Shakespeare and repeated, time and again, in what can only be described as fictitious reconstructions of events, have no historical accuracy whatever.

Diana Dunn, "The Queen at War: The Role of Margaret of Anjou in the Wars of the Roses" in War and Society in Medieval and Early Modern Britain (ed. Diana Dunn, University of Liverpool Press, 2000)

#margaret of anjou#edward of lancaster#mary of guelders#james iii of scotland#wars of the roses#battle of wakefield#historian: diana dunn

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Formation of the Valois Burgundian Empire - Charles the Bold

The last in a four part series on the formation of the Valois Burgundian Empire

Portrait of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy by Peter Paul Rubens

Charles the Bold, the fourth and last Valois Duke of Burgundy, was born to Isabel of Portugal on November 10, 1433, at Dijon, Burgundy. For political reasons, he was married to Catherine of Valois, daughter of King Charles VII of France. Once widowed, his father arranged a marriage to Isabella of Bourbon, who also died after…

View On WordPress

#Alsace#Battle of Nancy#Charles the Bold#Duke of Burgundy#Emperor Frederick III#Guelders#King of France#Lorraine#Louis XI#Low Countries#Mary of Burgundy#Maximilian of Habsburg#Valois dukes of Burgundy#Valois dynasty

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. The average age at first marriage among these women was 16.

This list is composed of princesses of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707.

Eadgyth (Edith) of England, daughter of Edward the Elder: age 20 when she married Otto the Great, Holy Roman Emperor in 930 CE

Godgifu (Goda) of England, daughter of Æthelred the Unready: age 20 when she married Drogo of Mantes in 1024 CE

Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I: age 12 when she married Henry, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1114 CE

Marie I, Countess of Boulogne, daughter of Stephen of Blois: age 24 when she was abducted from her abbey by Matthew of Alsace and forced to marry him, in 1136 CE

Matilda of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Henry the Lion in 1168 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry II: age 9 when she married Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170 CE

Joan of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married William II of Sicily in 1177 CE

Joan of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 11 when she married Alexander II of Scotland in 1221 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 21 when she married Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1235 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 9 when she married William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke in 1224 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Henry III: age 11 when she married Alexander III of Scotland in 1251 CE

Beatrice of England, daughter of Henry III: age 17 when she married John II, Duke of Brittany in 1260 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Edward I: age 24 when she married Henry III, Count of Bar in 1293 CE

Joan of Acre, daughter of Edward I: age 18 when she married Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester in 1290 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John II, Duke of Brabant in 1290 CE

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John I, Count of Holland in 1297 CE

Eleanor of Woodstock, daughter of Edward II: age 14 when she married Reginald II, Duke of Guelders in 1332 CE

Joan of the Tower, daughter of Edward II: age 7 when she married David II of Scotland in 1328 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of Edward III: age 33 when she married Enguerrand VII, Lord of Coucy in 1365 CE

Mary of Waltham, daughter of Edward III: age 16 when she married John IV, Duke of Brittany in 1361 CE

Margaret of Windsor, daughter of Edward III: age 13 when she married John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke in 1361 CE

Blanche of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 10 when she married Louis III, Elector Palatine in 1402 CE

Philippa of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 12 when she married Eric of Pomerania in 1406 CE

Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 20 when she married Henry VII in 1486 CE

Cecily of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married Ralph Scrope in 1485 CE

Anne of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 19 when she married Thomas Howard in 1494 CE

Catherine of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married William Courtenay, Earl of Devon in 1495 CE

Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 14 when she married James IV of Scotland in 1503 CE

Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 18 when she married Louis XII of France in 1514 CE

Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII: age 38 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1554 CE

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James VI & I: age 17 when she married Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1613 CE

Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 10 when she married William II, Prince of Orange in 1641 CE

Henrietta Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 17 when she married Philippe II, Duke of Orleans in 1661 CE

Mary II of England, daughter of James II: age 15 when she married William III of Orange in 1677 CE

Anne, Queen of Great Britain, daughter of James II: age 18 when she married George of Denmark in 1683 CE

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 10th 1460 King James III was crowned at Kelso Abbey.

His birthdate and birthplace are uncertain: either May 1452 at St. Andrew’s Castle or July 10, 1451 or July 20, 1451 at Stirling Castle. At birth, James was heir to the throne and became Duke of Rothesay, Prince and Steward of Scotland.

If you remember last week I posted about the 29-year-old James II, King of Scots was accidentally killed when a cannon nearby where he was standing exploded. As with the start of the reigns of James I and James II, Scotland once again had a child king.

Kelso was not your usual site for oor monarchs coronation and I can find little to say why it was chosen, except that it was hastily arranged, however his son, James IV would also go on to be crowned there.

James’s mother Mary of Guelders served as the regent for her nine-year-old son until her death three years later. The rest of the Scottish Stewarts, James IV, James V, Mary, Queen of Scots, and James VI, would also be child monarchs. James II’s death also continued the violent deaths of the Scottish Stuarts which started with the assassination of his father James I and continued with the deaths in battle of James III and James IV and the beheading of Mary, Queen of Scots.

In the power vacuum following the Queen’s death in 1463, James was “kidnapped” by his brothers, Robert Lord Boyd and Alexander Boyd and imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle (where he was taught chivalric pursuits).

The Boyds arranged the marriage of James to Margaret, the daughter of the King Christian I of Denmark in 1469. As a result of this union, Orkney and Shetland became part of Scotland in 1469.

James began to assert his own power at this time - executing one of the Boyds and exiling the other. But his demands for taxes and debasement of the currency did not go down well. He also tried to keep peace with England and this was not popular either. At one stage he was planning an invasion of the Low Countries but Parliament had to remind him that he should be looking after domestic affairs instead. Despite all this, he did reign for over 20 years, no mean feat in those days.

Relations with England deteriorated towards the end of the 1470s. Blackness Castle was torched by an English fleet in 1480. In 1482 an English army invaded Scotland in support of the cause of James’ brother, Alexander, Duke of Albany, as king. At this point, a group of Scottish nobles murdered some of the King’s favourites (a number of whom were low born) and imprisoned the King in Edinburgh castle as the English army advanced to Edinburgh. James survived by skilful negotiation and by giving up Berwick to the English. But following further conflicts with some of the Border families such as the Homes and Hepburns, whom James was trying to bring to heel, the nobles encouraged his 15-year-old son to lead a rebellion in 1488.

James III was subsequently killed in circumstances often debated either at or after the battle, I have posted about this several times before.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Goldsmith in his Shop by Petrus Christus

Netherlandish, 1449.

After the death of Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus modeled himself as the next van Eyck, who may have been his master when Christus was a student. He became the leading painter in Bruges and was active from 1444 until his death in 1475/76.

This piece is a bit of an enigmatic one as it's patron and intent isn't entirely clear. For a while, this painting was assumed to be a depiction of the patron saint of Goldsmiths, St. Eligius, and had a halo. However, further study revealed that this halo was a later addition and was removed. It's unclear when the halo was added, though the identification of the figure as St. Eligius might be traced back to a series of letters around the turn of the 19th century. It could be that this was a vocational portrait, one of the first portraits outside of an ecclesiastical setting in it's time, advertising a goldsmiths guild. It also may have been commissioned by Philip the Good as a gift to Mary of Guelders upon her marriage. If this is the case, the young couple may be intended as a portrait of the couple, shown buying rings and with a wedding girdle stretched upon the table before them. The painting celebrates the sanctity of marriage, and the cracked mirror in the foreground contrasts this sacrament with the figures in the street, who hold a falcon, a symbol of pride and greed, as a moral dichotomy. This mirror is also meant as a callback to van Eycks techniques of painting reflection, notably the similar convex mirror in his Arnolfini portrait.

Though this is not an ecclesiastical piece, it still holds potential hidden symbolism, such as the scales in the goldsmiths hands (a reference to St. Michael weighing souls), the coral in the background (a symbol of baby Jesus), and the chalice on the shelf (a symbol of the eucharist). Overall a piece with an interesting history.

#art history#art history student#art#oil painting#painting#renaissance#northern Renaissance#flemish#flemish art#netherlandish#netherlandish art#northern Renaissance art#Renaissance art#petrus christus#jan van eyck#a goldsmith in his shop

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

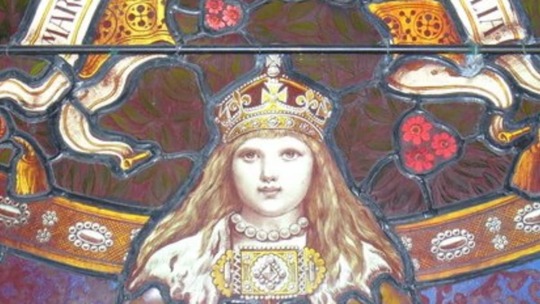

Mary of Guelders was the queen of Scotland by marriage to King James II of Scotland. She ruled as regent of Scotland from 1460 to 1463

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

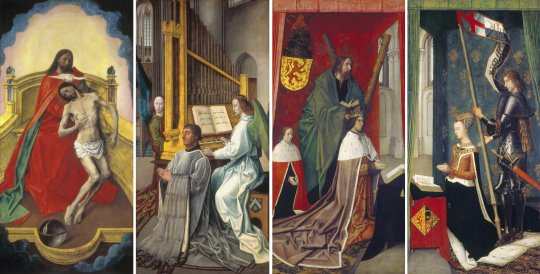

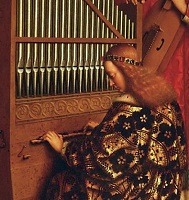

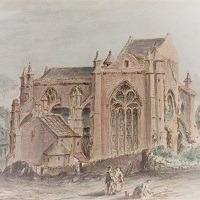

Historical Objects: The Trinity Altarpiece

(Click image for better view. Inside panels are on the right, outside on left. Source- wikimedia commons)

The Trinity Altarpiece is one of the most remarkable objects to have survived from mediaeval Scotland. Produced by Hugo van der Goes in the 1470s, this triptych would have occupied pride of place on the high altar of Trinity Collegiate Kirk in Edinburgh. Though the centre panel is now lost, the wings survive including depictions of the Holy Trinity, angels and saints. Perhaps of more interest are the contemporary historical figures depicted: on the outside of the left-hand panel is pictured the provost of Trinity kirk, Edward Bonkil; on the inside left-hand panel King James III (r.1460-1488), accompanied by a boy who may be the future James IV; and on the inside right-hand panel James III’s queen Margaret of Denmark. A precious survival from a country where only a small percentage of mediaeval art survived the iconoclasm of the Reformation, and centuries of Anglo-Scottish, religious, and civil wars, the Trinity Altarpiece gives a rare glimpse into the vibrant cultural networks of a small European kingdom and the interests of its elites.

This impressive piece was probably created by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes, who was born in the mid-fifteenth century in the great city of Ghent, then a major European centre. Goes was first mentioned in 1467, the same year he was admitted to the painters’ guild of Ghent. Over the next decade he frequently undertook painting work (both practical and artistic) in Ghent and further afield. He served as both juror and dean of the painters’ guild during the mid-1470s, but by 1478 had retired to the Roode Klooster near Brussels, where he lived for the rest of his life. In later years one of his fellow novices at the Roode Klooster, Gaspar Ofhuys, wrote an account of Goes’ time there, which provides a valuable insight into his life and character. Goes often received visitors, including Maximilian, Archduke of Austria and other notable figures. He was also occasionally allowed to leave the monastery to undertake commissions and travel to some of the region’s cities. While returning from one such trip to Cologne, however, he suffered a fit of madness and attempted suicide. He briefly recovered only to die shortly afterwards, in 1482, tormented towards the end of his life by the thought of not finishing his art. Nevertheless he is now recognised as one of the most significant and talented Flemish painters of his time, despite his short career- and the difficulty of identifying his work.

Most identifications of Hugo van der Goes’ paintings rest on similarities with the Portinari Altarpiece, the only work confidently attributed to him. Thus many of his purported works- which include the ‘Lamentation of Christ’ (now in Vienna), the ‘Adoration of the Kings’ (or the Monforte Altarpiece, now in Berlin), and others which only survive in copies made by his followers- cannot be certainly attributed, though as yet there is no real reason to doubt the Trinity Altarpiece. In any case the Trinity panels are clearly of the highest quality and represent an important contribution to Northern Renaissance art. Moreover, their existence sheds light on the networks of artistic patronage in mediaeval Europe and the links of one particular Scottish churchman and his royal patrons.

(The Portinari Altarpiece, also by Hugo van der Goes. The centre panel flanked by the inside of two wings gives some idea of how the Trinity Altarpiece would have looked when open, before the centre panel was lost. Source Wikimedia Commons)

While they are now appreciated primarily for their artistic value, these mediaeval altarpieces also had a practical purpose. As portable religious items they helped direct the spiritual devotions of their owners, while they also had worldly usefulness, prominently displaying the patron’s political, spiritual, and social networks. In triptychs, patrons and their family members were usually represented on the inside wings, like the royal figures in the Trinity Altarpiece. Here the king and queen of Scots- James III and Margaret of Denmark- are portrayed in rich costume, accompanied by Saints Andrew and George, and a young boy who probably represents their eldest son, James, Duke of Rothesay. Despite the prominence of the royal family however, the Altarpiece may owe its origin to a very different individual. When a triptych was not in use, the inner wings would usually close over a larger centre panel (the Trinity Altarpiece’s appears to have been lost) and the outside panels were often decorated with less showy ‘grisaille’ paintings. In the Trinity Altarpiece, however, these outer panels tell us even more about the work’s provenance. Portrayed on the left outer wing is the Holy Trinity (father, son, and holy spirit) and, on the right wing, kneeling in supplication before the Trinity, a churchman whose coat of arms identifies him as Edward Bonkil, first provost of Trinity Collegiate Church in Edinburgh- the man who probably commissioned this expensive work of art.

Trinity College Kirk, which stood beneath Calton Hill, was founded in 1460 as the pet project of Mary of Guelders, queen consort to James II of Scotland (1437-1460). Mary was not just the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders but also the great-niece of Philip the Good, the powerful Duke of Burgundy, and as Mary was raised at her uncle’s court her marriage to James II strengthened Scotland’s traditional commercial and cultural ties with the Low Countries. A formidable woman, Mary headed the government after her husband’s premature death in 1460, as regent for her young son James III. She also had some reputation as a builder (her other major project was Ravenscraig Castle, the first castle in Scotland built specifically to withstand artillery fire, and she contributed to works elsewhere too). Though work on the church may have begun in her husband’s lifetime, it was chiefly Mary’s project and from 1460 onwards she took a keen interest in the foundation. Besides paying for its endowment and construction, she may have personally contributed to the creation of the college rules, stipulating that all the canons and boys should be capable of reading and singing in plain chant and descant, laying the foundations of Trinity’s reputation as a prestigious choral institution. Following her early death in 1463, she was also buried in the church, probably near the high altar, where the altarpiece likely stood and it has been theorised that the missing middle panel could have included a representation of the queen dowager herself, drawing attention to the church’s royal associations. However the altarpiece was painted after her death, and indeed the responsibility for commissioning this costly piece of art may not have lain with the royal family at all, although Mary’s son James III and his queen feature prominently on its inner panels. It has been argued by Lorne Campbell that we should instead look to the provost of Trinity, Edward Bonkil, portrayed on the right-hand outer panel of the altarpiece.

(Bottom left- Trinity College Kirk, as it appeared in the nineteenth century. Source- Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Bonkil had been a close servant of the late Mary of Guelders, having been personally promoted to the position of provost of her lavish foundation. After the dowager’s death, however, he seems to have gradually fallen out of favour at court and it is suggested by Campbell that he may have commissioned the altarpiece partly with a view to currying favour with the young James III. Whether this is accurate or not, it seems highly probable that Bonkil was the main driving force behind the commission- not only does he occupy a privileged position on the outer wing of the altarpiece, but his features are much more detailed and exact than those of the royal family, suggesting that they were painted from life. As a member of a prominent Edinburgh merchant family, and having possibly served on embassies to Guelders and Burgundy, Bonkil had close connections with the Low Countries. Moreover he is not recorded in Scotland between 1473 and 1476, around the time that the altarpiece may have been painted, and so he could have travelled to Flanders personally to sit for the artist. Though it did not bring him renewed royal favour, if the altarpiece was commissioned by Bonkil it not only secured his legacy but has provided us with a rare and invaluable glimpse into the tastes and cultural connections of late mediaeval Scotland’s clerical elite.

Much of the altarpiece, including the likeness of Bonkil, is believed to have been painted in Flanders by Goes, and certain sections are even adapted from other works by Flemish artists, such as the ‘Madonna in the Church’ by Jan Van Eyck, which forms the backdrop to Bonkil’s panel, and a lost work by Robert Campin which influenced the representation of the Trinity. The faces of King James III and Queen Margaret however, may have been painted over by an unknown artist upon the altarpiece’s arrival in Scotland, to lend them some realism, though they are not of such high quality as the depiction of Bonkil. The portrayal of the young Duke of Rothesay- the future James IV- is probably even less true to life, as portrayals of children in late mediaeval art were more often symbolic than realistic and it is probable that Rothesay was an infant at most at the time of the painting’s creation. His appearance may allow us to tentatively date the work however, as he was born in 1473 and described as James III’s ‘only son’ until 1478-9, and neither of his younger brothers are portrayed in the painting. This place the period of production in the mid-1470s- a rare survival then, from an otherwise shadowy period in late mediaeval Scottish history.

(Edward Bonkil, Provost of Trinity Collegiate Church, who probably commissioned the altarpiece. Source- wikimedia commons)

Despite having been painted almost a century and a half earlier however, the panels from the Trinity Altarpiece were only recorded in written sources for the first time in 1617, when they were included in an inventory taken of the possessions of Anne of Denmark, queen of James VI of Scotland (James III’s great-great grandson and by now James I of England also). The inventory of Queen Anne’s belongings was taken at the royal residence of Oatlands in Surrey, and it has been suggested that the Trinity Altarpiece was brought south after her husband’s last visit to Scotland earlier in 1617. It was to remain in England for many years thereafter, passing into the hands of Anne’s son, Charles I, by 1624, when it was erroneously described as a work by Jan van Eyck. The altarpiece was auctioned off during the Civil War but was reclaimed by the royal family after the Restoration, after which it was displayed in various English royal palaces, including Kensington and Hampton Court. In 1857, it returned to Scotland for the first time in over two hundred years when it was briefly transferred to Holyrood Palace during the reign of Queen Victoria. Over the next few decades it was shuffled around on several occasions, but was often on public display at Holyrood until 1912, when it was first briefly loaned to the National Gallery of Scotland, due to fears over its safety in the face of militant suffragette activity. In 1931, it again returned to the National Gallery, in whose care it remains today.

If anyone has a spare half an hour in Edinburgh some day, I highly recommend visiting the galleries, if only to see the Altarpiece. Flemish art of this period is both fascinating and beautiful and the Galleries are very fortunate to own a piece of such high calibre as the Trinity Altarpiece. As well as this, the culture of mediaeval Scotland has left few traces in the modern day: even the impressive Trinity Collegiate Church, the original home of the altarpiece, was largely demolished in the Victorian period to make way for Waverley Station, while many other pieces of art, books, buildings, music and historical sources have been lost to the ravages of war, iconoclasm, and time. The survival of such a beautiful and costly work as the Trinity Altarpiece, therefore, stands testament to a fascinating and complex past, as culturally vibrant as that of any other corner of mediaeval Europe, and just waiting to be uncovered.

(Source - Wikimedia commons)

Selected Bibliography:

“Charters and documents relating to the Collegiate Church and Hospital of the Holy Trinity, and the Trinity Hospital, Edinburgh, A.D. 1460-1661″, ed. J.D. Marwick

“Rotuli scaccarii regum Scotorum: the Exchequer Rolls of Scoltand”, eds. John Stuart and George Burnett, volumes 6, 7, & 8

“Hugo van der Goes and the Trinity Panels in Edinburgh”, C. Thompson and L. Campbell

“Hugo van der Goes’s Altarpiece for Trinity College in Edinburgh and Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scotland”, T. Tolley

“She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland, 1424-1463″, Fiona Downie

National Galleries of Scotland

#Scottish history#art history#early Netherlandish#Northern Renaissance#Flemish history#Flanders#the Low Countries#Hugo van der Goes#Edward Bonkil#Mary of Guelders#James III#Margaret of Denmark#art#historical objects#culture#fifteenth century#late middle ages#Trinity Collegiate Church#Holy Trinity#Edinburgh#Ghent#painting#James IV#Scotland and the World#religion#kirk and people#National Gallery of Scotland#Christianity#the Stewarts#Living in Medieval Scotland

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

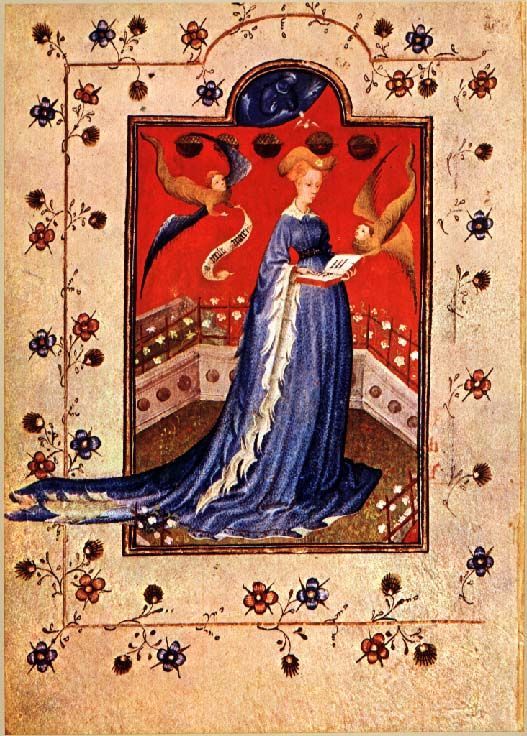

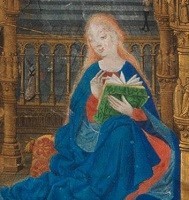

History Edits: Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scots

Born on 17th January 1433 in Grave, now in the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant, Mary of Guelders was the eldest of the surviving children of Arnold, Duke of Guelders (an area roughly approximating to modern-day Gelderland, but larger) and Catherine of Cleves. She was also the great-niece of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and it was due to this connection that in the duke arranged for her to be raised in the household of his wife Isabel of Portugal in 1442. The fifteenth century court of Burgundy was one of the most glittering and influential courts in western Europe and Mary would not only have been schooled in etiquette and courtly behaviour, but she would also have seen the formidable Duchess Isabel in action. It also appears to have been due to these Burgundian links that she was married to James II of Scotland in 1449, though the duchess and many other members of the Burgundian court wept when Mary departed from Bruges. The sumptuous wedding feast was thoroughly chronicled by Mathieu d’Escouchy, who attended along with several other notable figures from France and the Low Countries. Mary’s impressive dowry was provided by her great-uncle Philip the Good- who had no daughters of his own so used other female relatives to forge alliances- but it also came with the stipulation that she be kept in the style she was accustomed to, and soon enough Mary became a very rich woman- though sometimes indirectly as a result of her husband’s forfeitures of major nobles. Aside from her dowry, Mary’s marriage to James II was probably the reason why the great bombard Mons Meg- one of the largest cannons of its kind in history- was given to the king of Scots by Philip the Good. Scotland’s relationship with the Low Countries had always been important but Mary of Guelders’ marriage not only helped to bolster trade between the two, but also strengthened diplomatic relations with the dukes of Burgundy, as well as her homeland of Guelders. In later years, her second son Alexander, Duke of Albany, was to raised at his grandfather’s court of Guelders, and the family connections which the marriages of Mary and her husband’s sisters forged between the Stewarts and continental dynasties opened up important artistic and political channels for several generations after her death, not least during the reign of her son.

In her eleven years as queen consort Mary gave birth to upwards of seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood- Mary, Countess of Arran; the future James III; Alexander, Duke of Albany; John, Earl of Mar; and Lady Margaret Stewart. Her marriage was cut short suddenly in 1460, however, when one of her husband’s cannon exploded when he was standing nearby, and James died from blood loss soon after. At the time of his death he had been besieging Roxburgh Castle, formerly one of the most important castles in Scotland but which had been in English hands for around a century, and popular tradition has it that it was Mary who personally spurred on her husband’s troops to finish the job and take the castle, after which Roxburgh was razed to the ground and never rebuilt. She then acted as a regent (loosely) to her young son James III. While traditionally it was claimed that Mary was unstable and showed no aptitude for government, busying herself with taking a string of lovers instead, in more recent years these rumours- which were mostly the product of the political rivalries of James III’s minority- have been largely dispelled and her considerable political acumen and impact has been more widely acknowledged. In particular her foreign policy- previously thought of as ‘wayward’- actually seems to have been very intelligent, particularly when Mary protected Scotland’s interests during the civil war which was then disrupting Scotland’s neighbour England (i.e. the Wars of the Roses), and while she cautiously lent support to certain factions, she made sure not to overplay her hand and never inclined too much towards one party, in case it should endanger Scotland’s position. She did however on more than one occasion harbour the Lancastrian queen Margaret of Anjou, along with her husband Henry VI and young son, in Scotland. In 1461 a conference was held between the queens of Scotland and England at Lincluden, whereby it was agreed that the Scots would provide troops and support to the House of Lancaster, while Berwick-upon-Tweed would be returned to Scotland and Mary’s eldest daughter and namesake Mary Stewart would marry Margaret’s son, Edward Prince of Wales. This marriage never took place however, and Mary was eventually persuaded by her Burgundian relatives to drop the Lancastrian alliance, though she also rejected the marriage which was briefly proposed between herself and the Yorkist king Edward IV of England.

Mary also made an impact on domestic life in Scotland in several different ways. She has acquired a reputation as a builder, and her most notable projects included a new castle at Ravenscraig in Fife, which was the first castle in Scotland specifically built to withstand artillery fire, and also Trinity Collegiate Church in Edinburgh. This last project also displays Mary’s spiritual patronage (she was also later credited with having introduced the Observant Franciscans to Scotland) as well as her interest in music, and among other things she provided organs for the church’s use and stipulated that all the clerics were to be able to sing in matins.

Mary was eventually buried in Trinity Kirk when she died prematurely in December 1463, a month short of her 31st birthday, having been ill for some time. The kirk was eventually bulldozed to make way for Waverley Station, and it is unclear whether it was actually Mary’s body that was moved to Holyrood Abbey at this time or another unknown woman. In the fifteenth century however, she was mourned both in her homeland of Guelders and in Scotland. Mary had only been at the head of government for three years but in that time proved herself a capable administrator and strong ruler, whilst she had also made a notable contribution to Scotland’s international relations- both diplomatic and economic- and its religious life, as well as fostering its military strength and supporting new technology in an age where warfare was changing massively. She is still a very shadowy figure for all this, however, and the lack of information available about her life and world do not help us to dispel some of the older assumptions about her rule. We don’t even have any contemporary artistic portrayals of her. Nonetheless though she died relatively young and while she must remain a mysterious figure in many ways, Mary of Guelders was for a short time able to exercise an important influence in both Scotland and arguably even Britain as a whole, and her impact on mid fifteenth century Scotland should not be underestimated.

Read more about Mary here, here, and if looking for books here’s some good places to start x, x (pretty sure there’s much much cheaper versions elsewhere because these books are not usually so expensive but I just wanted to give the titles. Also this book is good for Guelders. And there are lots of primary sources online, including the account of Mary’s wedding by Mathieu d’Escouchy).

#Mary of Guelders#Scottish history#women in history#British history#fifteenth century#shoddy history gifsets#Guelders

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary of Guelders depicted by William Brassey Hole

The Ballad — Music is an essential part of Scottish culture. Ballads, or ‘muckle sangs’ in Scots, have been an important way of telling and passing down stories since the Middle Ages. The Ballad, shows a minstrel entertaining ladies of the royal court [presumedly, Mary of Guelders is sitting on the throne, as her coat of arms are above]. Although rooted in the fifteenth century through its historical detail, it does not represent a specific event but symbolises a time of peace.

King James III presented to the Nobles by his Mother at the Siege of Roxburghe A.D. 1460 — James II was mortally wounded when one of his own cannons exploded during the capture of Roxburgh Castle. He is shown lying in state on the left, with the cannon and the castle in the background. The king’s widow, Mary of Guelders (about 1434-1463), presented her eight-year-old son, the future King James III (1451-1488), as a way of encouraging the soldiers despite this shocking accident. The siege ended two days after the death of James II with an English defeat.

#historyedit#history#kingdom of scotland#scottish history#art history#mary of guelders#james iii#james ii#house of stewart#15th century#medieval history#qc: mary of guelders#k: james ii#k: james iii#ours#*artwork

119 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Too fragile to touch, too beautiful to remain unknown. The prayer book that once belonged to Duchess Mary of Guelders is the greatest work of art from medieval Guelders. In 2015, this book will be exactly six hundred years old. It’s famous but unknown, since it cannot be examined before undergoing extensive restoration. Medievalist Johan Oosterman wants to achieve this with your help.

More information: http://crowdfunding.ru.nl/projecten/red-het-gebedenboek-van-maria-van-gelre

This crowdfunded project is now fully funded (yay!), but you’ll still want to watch the video to see this fantastic manuscript.

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[AU: what if the Union of the Crowns had happened... centuries earlier before James VI of Scotland became King of England?]

Margaret, Maid of Norway, becomes Queen of Scotland by right. In an accordance with Edward, King of England, she keeps the independence of the realm to a certain degree if she marries his son, the prince of Wales. Eventually, she is espoused by Edward of Caernarfon, but the marriage is complicated in the beginning. However, Edward and Margaret eventually settle together and their marriage produce the following children:

1. Edward III of England and I of Scotland. He takes as wife Philippa of Hainault, by whom he has 13 children. Edward is the responsible for splitting the realms again... He makes Lionel, his favourite son, the king of Scotland, whilst appointing Edward, his oldest son, heir to England. Lionel takes as wife a granddaughter of the powerful nobleman Robert the Bruce.

2. Margaret, Queen of Norway. She marries Margaret’s nephew, her first cousin, by whom she has at least three children.

3.Eric, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor. He takes as wife a daughter of the duke of Burgundy.

4.Eleanor, Duchess of Brittany. Named after Margaret of Scotland’s grandmother, this princess is espoused by the duke of Brittany, by whom she has at least 5 children.

5.Henry, Duke of Albany. He takes as wife a daughter of the king of France. They have issue.

6. William, Earl of Cornwall. He takes as wife a granddaughter of Alfonso X of Castille.

7. Mary, Countess of Guelders. She is espoused by the Earl of Guelders, but they don’t have issue.

#i do NOT claim to own any of those gifs#found them online with the ONLY purpose to play with history#if however any of these gifs belong to anyone please let me know so I can credit them properly#margaret of norway#maid of norway#queen of scots#edward ii#king of england#plantagenet#alternative universe#charlize theron#freya allan#essie davies#fancast#timothee chalamet

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 3rd 1449 James II took formal control of his kingdom following his marriage to Marie of Guelders, niece of the Duke of Burgundy in Holyrood Abbey.

Marie, or Mary as she became known in Scotland had been earmarked to marry Charles, Count of Maine, but her father could not pay the dowry. Negotiations for a marriage to James II in July 1447 when a Burgundian envoy went to Scotland and were concluded in September 1448. Philip promised to pay Mary’s dowry, while Isabella paid for her trousseau. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy settled a dowry of 60,000 crowns on his great-niece and Mary’s dower (given to a wife for her support in the event that she should become widowed) of 10,000 crowns was secured on lands in Strathearn, Athole, Methven, and Linlithgow.

William Crichton, Lord Chancellor of Scotland was sent to Burgundy to escort her back and they landed at Leith on June 18, 1449. Marie was 15 and James 19 when the two wed on July 3rd and immediately after the marriage ceremony, Mary was dressed in purple robes and crowned Queen of Scots. Consort by Abbot Patrick.

A sumptuous banquet was given, while the Scottish king gave her several presents. The Queen during her marriage was granted several castles and the income from many lands from James, which made her independently wealthy. In May 1454, she was present at the siege of Blackness Castle and when it resulted in the victory of the king, he gave it to her as a gift. She made several donations to charity, such as when she founded a hospital just outside Edinburgh for the indigent; and to religion, such as when she benefited the Franciscan friars in Scotland. The couple had six children, the oldest James, became James III.

James II died when a cannon exploded at Roxburgh Castle on August 3rd, 1460, before his death he had ordered another castle be built for his wife who was left to oversee it’s construction as a memorial to him, Ravenscraig was still being built when Marie moved into east tower. She also founded Trinity College Kirk in Edinburgh’s Old Town in his memory, she herself died and was buried there in 1483, the old Kirk was demolished, amid protests in 1833 and Marie was interred at Holyrood Abbey.

The pic is a “Tableau Vivant with the Marriage of James II of Scotland to Mary of Gelre-Egmond in 1449 by Pieter but dates to about 200 years later.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every English Princess Ever

You’ve heard of Every Queen of England Ever, now I present to you another product that proves I have way too much time on my hands! If you notice any mistakes, please point them out to me kindly. I am sorry I do not know everything, but there is no reason to be rude. 😁

Æthelswith - Daughter of Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh. She married King Burgred of Mercia in 853, making her the Queen of Mercia.

Æthelflæd - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. When her husband Æthelred, Lord of Mercians died in 911, she became Lady of the Mercians, and reigned for seven years.

Æthelgifu - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. When Alfred founded Shaftesbury Abbey in 890, he made her its first abbess.

Ælfthryth - Daughter of Alfred the Great and Ealhswith. Her marriage to Baldwin II, Count of Flanders made her Countess of Flanders.

Eadgifu - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She was Queen of West Francia by her marriage to Charles III.

Eadhild - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She married Hugh, Duke of the Franks in 937.

Eadgyth - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife Ælfflæd. She married Otto in 930, who became Otto I, King of Germany in 936, also making her Queen of Germany.

Eadburh - Daughter of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu. She lived her life as a nun.

Godgifu - Daughter of Æthelred the Unready and his second wife Emma of Normandy. Her marriage to Eustace II, Count of Boulogne made her Countess of Boulogne.

Gunhilda - Daughter of Cnut the Great and his second wife Emma of Normandy. She became Queen of Germany when she married Henry III.

Gytha - Daughter of Harold II and Edith Swanneck. She was Princess of Rus from her marriage to Vladimir II Monomakh.

Adeliza - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders.

Cecilia - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She was entered into the Abbey of the Holy Trinity of Caen at a young age, and became Abbess in 1112.

Constance - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She became Duchess of Brittany when she married Alan IV, Duke of Brittany.

Adela - Daughter of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. She was Countess of Blois by her marriage to Stephen, Count of Blois, and was regent of Blois two times.

Empress Matilda - Daughter of Henry I and Matilda of Scotland. She became Holy Roman Empress in 1114, and acted as Queen of England from 1141 to 1148, but was disputed.

Marie I - Daughter of Stephen and Matilda I, Countess of Boulogne. When her brother William I, Count of Boulogne died childless in 1159, Marie succeeded him as the Countess of Boulogne.

Matilda - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was Duchess of Saxony and Bavaria from her marriage to Henry the Lion.

Eleanor - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She became Queen of Castile and Toledo when she married Alfonso VIII.

Joan - Daughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was Queen of Sicily by her marriage to William II until his death in 1189, and became Countess of Toulouse when she married Raymond VI in 1196.

Joan - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to Alexander II.

Isabella - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Holy Roman Empress and Queen of Sicily and Germany by her marriage to Frederick II.

Eleanor - Daughter of John and Isabella of Angoulême. She was Countess of Pembroke by her first marriage to William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, and Countess of Leicester by her second marriage to Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester.

Margaret - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to Alexander III.

Beatrice - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. (Her wikipedia says she was Countess of Richmond, which I’m not sure is true or not. Her husband was the Duke of Brittany, but it is possible she somehow inherited the title in her own right).

Katherine - Daughter of Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. She passed away at the age of three.

Eleanor - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Bar by her marriage to Henry III, Count of Bar.

Joan of Acre - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Hertford and Gloucester by her first marriage to Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester and 6th Earl of Hertford.

Margaret - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Duchess of Brabant, Lothier and Limburg by her marriage to John II.

Mary of Woodstock - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was a nun at Amesbury Priory.

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan - Daughter of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was Countess of Holland by her first marriage to John I, and Countess of Hereford by her second marriage to Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford.

Eleanor of Woodstock - Daughter of Edward II and Isabella of France. She was Duchess of Guelders by her marriage to Reginald II, and was regent of Guelders while her son was still young.

Joan of the Tower - Daughter of Edward II and Isabella of France. She got her name from being born in the Tower of London. Joan was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to David II.

Isabella - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Countess of Bedford and Lady of Coucy by her marriage to Enguerrand VIII, and was made a Lady of the Garter in 1376.

Joan - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She died during the Black Death at the age of fourteen.

Mary of Waltham - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Duchess of Brittany by her marriage to John IV, Duke of Brittany, and was made a Lady of the Garter in 1378. She died young at the age of sixteen.

Margaret of Windsor - Daughter of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. She was Countess of Pembroke by her marriage to John Hastings, 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Margaret died young at the age of fifteen.

Blanche of Lancaster - Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun. She was Electress Palatine by her marriage to Louis III, Electress Palatine.

Philippa of Lancaster - Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun. She was Queen of Denmark, Sweden and Norway by her marriage to Eric III, VIII & XIII.

Elizabeth of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was Queen of England by her marriage to Henry VII.

Mary of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She died at the age of fourteen.

Cecily of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was First Lady of the Bedchamber to her sister, Elizabeth of York, from 1485 to 1487. Cecily was Viscountess Welles by her marriage to John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles.

Margaret of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She died at just eight months old.

Anne of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was First Lady of the Bedchamber to her sister, Elizabeth of York, from 1487 to 1494.

Catherine of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was Countess of Devon by her marriage to William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon.

Bridget of York - Daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. She was a nun at Dartford Priory.

Margaret Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She was Queen of Scotland by her marriage to James IV of Scotland.

Elizabeth Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She died at the age of three.

Mary Tudor - Daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She was Queen of France by her first marriage to Louis XII of France, and Duchess of Suffolk by her second marriage to Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk.

Mary I - Daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. She was Queen of England from 1553 to 1558, and Queen of Spain by her marriage to Philip II of Spain.

Elizabeth I - Daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. She was Queen of England from 1558 to 1603.

Elizabeth Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She was Electress Palatine and Queen of Bohemia by her marriage to Frederick V.

Margaret Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She died at the age of one year old.

Mary Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She died at the age of two years old.

Sophia Stuart - Daughter of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark. She lived for just one day.

Mary - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She was Princess of Orange and Countess of Nassau by her marriage to William II, Prince of Orange.

Elizabeth Stuart - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She died at the age of fourteen.

Anne Stuart - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She died at the age of three.

Henrietta - Daughter of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. She was Duchess of Orléans by her marriage to Philippe I, Duke of Orléans.

Mary II - Daughter of James II & VII and Anne Hyde. She was Queen of England from 1689 to 1694.

Anne - Daughter of James II & VII and Anne Hyde. She was Queen of England and Great Britain from 1702 to 1714.

Louisa Maria Stuart - Daughter of James II & VII and Mary of Modena. She died at the age of nineteen.

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover - Daughter of George I and Sophia Dorothea of Celle. She was Queen of Prussia and Electress Brandenburg by her marriage to Frederick William I of Prussia.

Anne - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Princess of Orange by her marriage to William IV, Prince of Orange.

Amelia of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach.

Caroline Elizabeth of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach.

Mary of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel by her marriage to Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel.

Louise of Great Britain - Daughter of George II and Caroline of Ansbach. She was Queen of Denmark and Norway by her marriage to Frederick V of Denmark.

Charlotte - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Duchess, Electress and Queen of Württemberg by her marriage to Frederick I of Württemberg.

Augusta Sophia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Elizabeth - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg by her marriage to Frederick VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg.

Mary - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh by her marriage to Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh.

Sophia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Amelia - Daughter of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Charlotte of Wales - Daughter of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick. She was their only child, and died before both of them.

Charlotte Augusta Louisa of Clarence - Daughter of William IV and Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. She died shortly after birth.

Elizabeth Georgiana Adelaide of Clarence - Daughter of William IV and Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. She died shortly after birth.

Victoria - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was German Empress and Queen of Prussia by her marriage to Frederick III, German Emperor.

Alice - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Grand Duchess of Hesse and Rhine by her marriage to Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse.

Helena - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Princess of Schleswig-Holstein by her marriage to Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein.

Louise - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Duchess of Argyll and Viceregal of Canada by her marriage to John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll.

Beatrice - Daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was Princess of Battenberg by her marriage to Prince Henry of Battenberg.

Louise of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark. She was Duchess of Fife by her marriage to Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife.

Victoria of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark.

Maud of Wales - Daughter of Edward VII and Alexandra of Denmark. She was Queen of Norway by her marriage to Haakon VII of Norway.

Mary of York - Daughter of George V and Mary of Teck. She was Countess of Harewood by her marriage to Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood.

Elizabeth II - Daughter of George VI and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. She is Queen of the UK from 1952 to present.

Margaret Rose of York - Daughter of George VI and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. She was Countess of Snowdon.

Anne of Edinburgh - Daughter of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip.

#british history#historical women#empress matilda#elizabeth of york#margaret tudor#mary i#elizabeth i#british royal family

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Adriaen Hanneman - William III, Prince of Orange when a child - 1664

William III (William Henry; Dutch: Willem Hendrik; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702),[b] also widely known as William of Orange, was sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the 1670s and King of England, Ireland, and Scotland from 1689 until his death in 1702. As King of Scotland, he is known as William II. He is sometimes informally known as "King Billy" in Ireland and Scotland. His victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 is commemorated by Unionists, who display orange colours in his honour. Popular histories usually refer to his joint reign with his wife, Queen Mary II, as that of "William and Mary".

William was the only child of William II, Prince of Orange, who died a week before his birth, and Mary, Princess of Orange, the daughter of Charles I of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In 1677, during the reign of his uncle Charles II of England, Scotland, and Ireland, he married his cousin Mary, the eldest daughter of his maternal uncle James, Duke of York. A Protestant, William participated in several wars against the powerful Catholic king of France, Louis XIV, in coalition with both Protestant and Catholic powers in Europe. Many Protestants heralded him as a champion of their faith. In 1685, his Catholic uncle and father-in-law, James, became king of England, Scotland, and Ireland. James's reign was unpopular with the Protestant majority in Britain, who feared a revival of Catholicism. Supported by a group of influential British political and religious leaders, William invaded England in what became known as the Glorious Revolution. In 1688, he landed at the south-western English port of Brixham. Shortly afterwards, James was deposed.

William's reputation as a staunch Protestant enabled him and his wife to take power. During the early years of his reign, William was occupied abroad with the Nine Years' War (1688–97), leaving Mary to govern the kingdom alone. She died in 1694. In 1696, the Jacobites plotted unsuccessfully to assassinate William and return his father-in-law to the throne. William's lack of children and the death in 1700 of his nephew Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, the son of his sister-in-law Anne, threatened the Protestant succession. The danger was averted by placing distant relatives, the Protestant Hanoverians, in line to the throne with the Act of Settlement 1701. Upon his death in 1702, the king was succeeded in Britain by Anne and as titular Prince of Orange by his cousin, John William Friso.

Adriaen Hanneman (c. 1603 – buried 11 July 1671) was a Dutch Golden Age painter best known for his portraits of the exiled British royal court. His style was strongly influenced by his contemporary, Anthony van Dyck.

25 notes

·

View notes