#paul grimault

Text

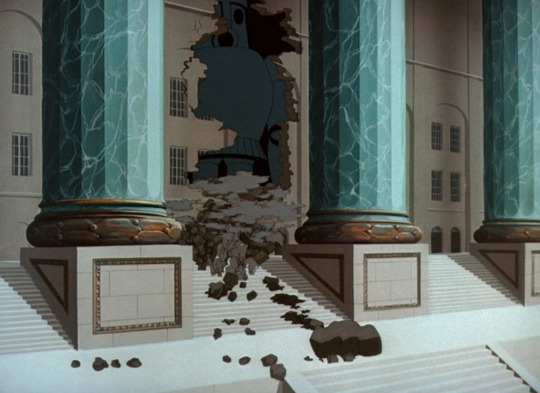

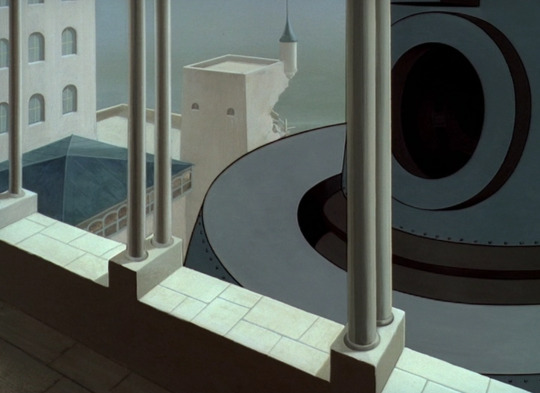

The King and the Mockingbird (1980)

#the king and the mockingbird gif#le roi et l'oiseau#paul grimault#jacques prévert#french animation#french movies#giant robot#80s movies#50s movies#1952#1980#gif#chronoscaph gif

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Roi et L'Oiseau (1980)

Les Appartements Secrets de Sa Majesté

#le roi et l'oiseau#the king and the mockingbird#french film#french animation#paul grimault#1950s movies#french cinema#jacques prévert#french side of tumblr#1980s movies#aesthetic#1950s aesthetic#old movies#vintage#up the baguette#french stuff

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry not sorry but we, French people, have the best movies and the best movie-makers ever

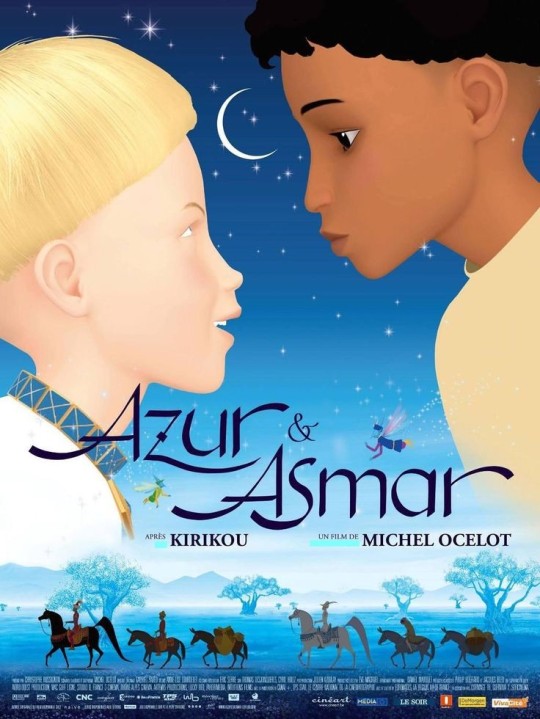

Kirikou et la sorcière

Princes et princesses

Dragons et princesses

Azur et Asmar

All of them by Michel Ocelot

And, obviously, THE movie that got THE Miyazaki inspired to do his:

Le roi et l'oiseau, by Paul Grimault

This one is probably my favourite movie of ALL time.

Like.

It's brilliant.

I loved it when I was a child, I still love it now for different reasons. The double meanings are incredible, the animation is SO DAMN GOOD (and the film was released in 1980) (it took over 30 years to make because the production was a disaster but the result is... MASTERPIECE)

#Watch these#French movies#Michel Ocelot#the king and the mockingbird#Le roi et l'oiseau#Paul Grimault#Azur et Asmar#Princes et Princesses#Dragons et princesses#Kirikou et la sorcière#kirikou et les bêtes sauvages#Kirikou et les hommes et les femmea

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fumito Ueda was inspired by… The King and the Mockingbird (Le Roi et l'Oiseau).

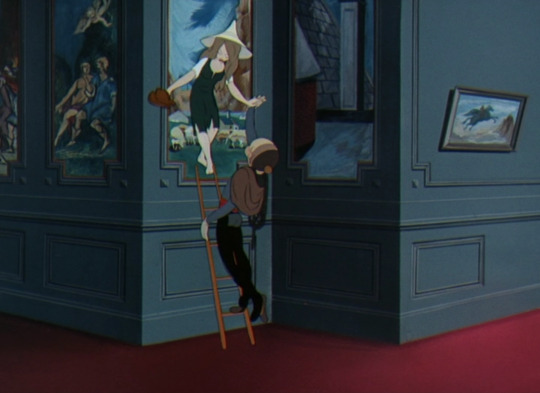

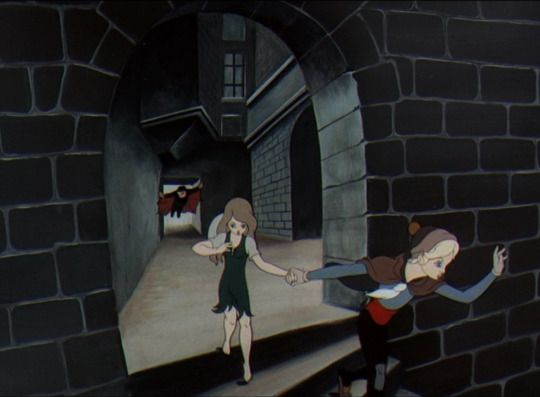

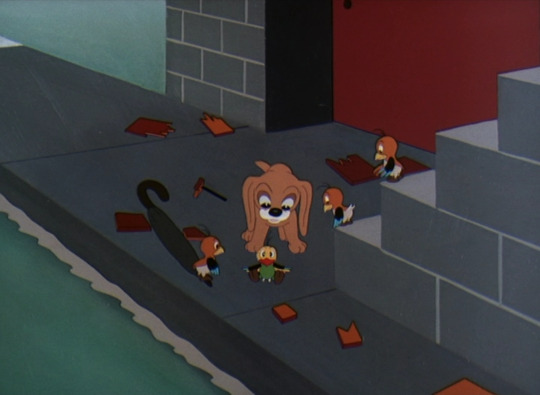

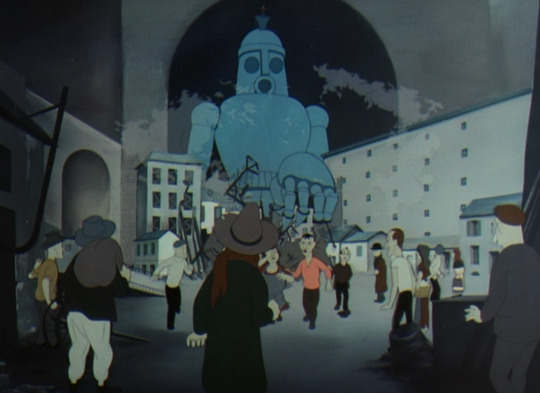

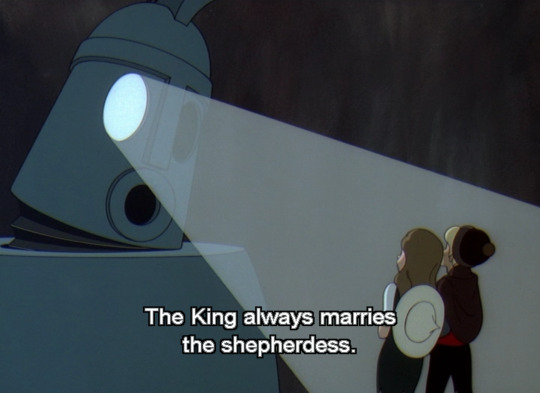

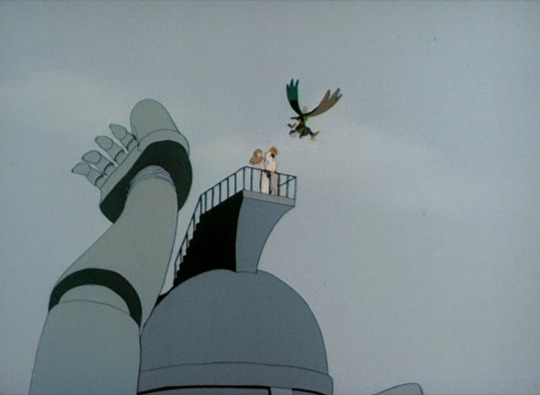

The King and the Mockingbird was clearly an inspiration for both Hayao Miyazaki and Fumito Ueda. I've taken so many screenshots that look like scenes in The Castle of Cagliostro, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, Ico and Shadow of the Colossus that I can't include all of them in one post, so first I'm going to show you the ones that look like Ico.

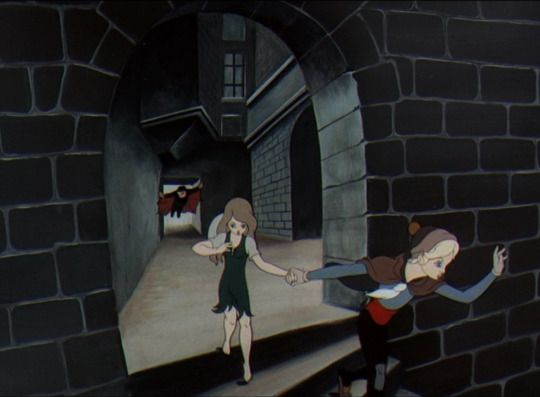

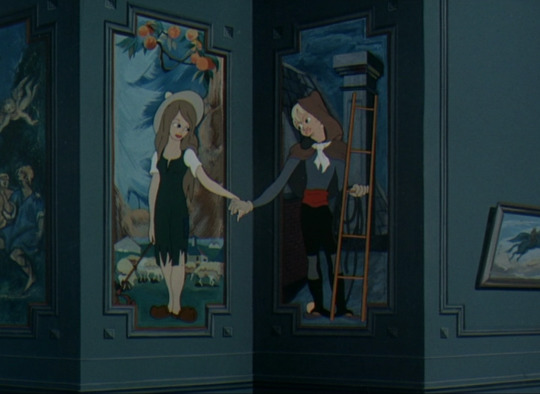

A chimney sweep and a shepherdess are the young couple escaping the castle, prefiguring Ico and Yorda. They come to life from paintings hanging next to each other and the reason they need to escape is because a painting of the king has also come to life, has got rid of the actual king, and is determined to marry the shepherdess.

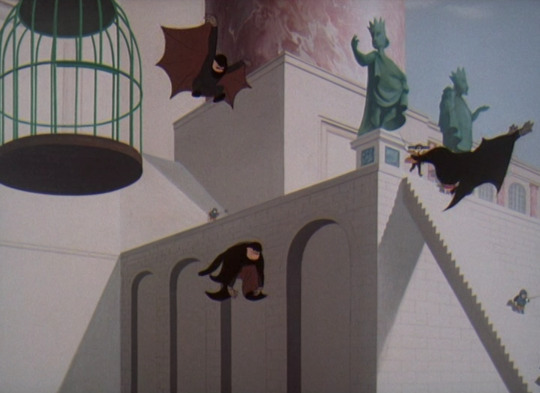

The narcissistic king has winged servants who chase after the shepherdess and the chimney sweep like the flying monkeys of The Wizard of Oz and surely inspiring the shadow creatures in Ico.

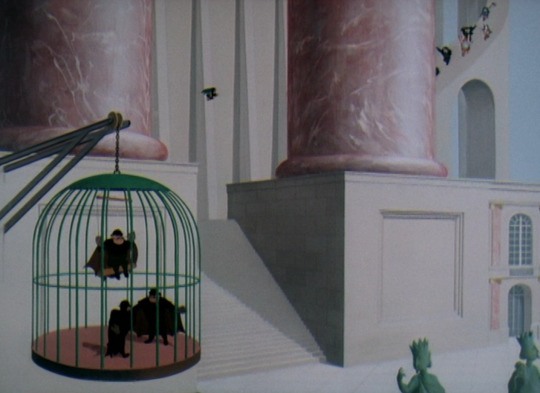

The mockingbird of the title looks after four hatchlings. One of them keeps getting trapped in a cage and on one occasion is freed when the cage falls to the ground and breaks open, just like when we first encounter Yorda in Ico.

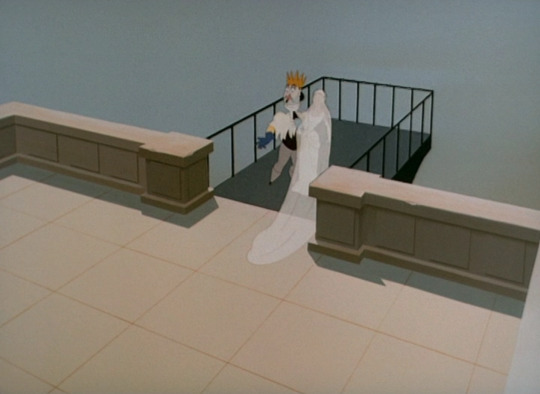

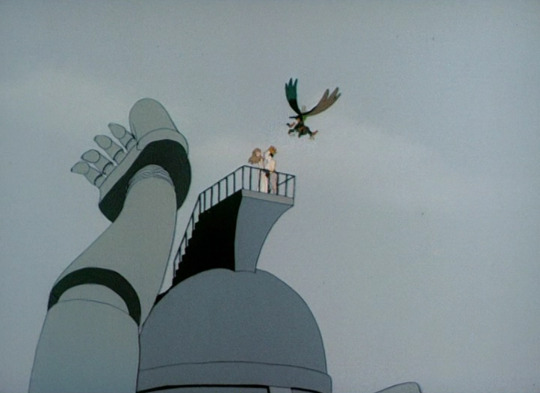

Towards the end, the king is trying to get away with the shepherdess, who is his unwilling bride. He steps onto a balcony area which then moves away from the palace and is revealed to be the helmet of the king's enormous robot, so it's like a combination of the retracting bridge from Ico and Malus in Shadow of the Colossus.

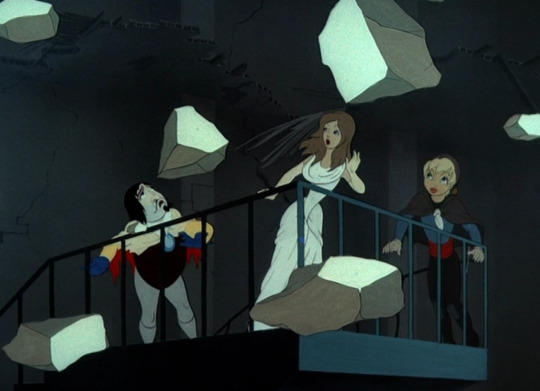

Not long after, it is the king, rather than our hero, who gets hit by a falling rock as the castle crumbles.

The soundtrack -

When we’re looking at the paintings of the shepherdess and the chimney sweep (at 16 minutes 30 seconds) we hear a harpsichord melody called ‘La Bergere et le Ramoneur’ that's strikingly similar to 'Castle in the Mist'.

Also, whenever the shepherdess and the chimney sweep need the mockingbird's help, they call out ‘Oiseau’ (pronounced ‘Wuh-zoh’) the way Ico calls out ‘Ontwuh’.

Ico's horns -

They don't feature in this animation but perhaps they should because....

The King and the Mockingbird was adapted from a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale called The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep. It tells the story of a shepherdess who is told she has to marry a creature with horns and the legs of a goat (a description of a satyr).

Is it any surprise at all that a fairy tale as beautiful as Ico should turn out to be traceable all the way back to none other than Hans Christian Andersen?

#the king and the mockingbird#le roi et l'oiseau#the shepherdess and the chimney sweep#ico#ico and yorda#yorda#fumito ueda#shadow of the colossus#hayao miyazaki#the castle of cagliostro#laputa#castle in the sky#hans christian andersen#flying creatures#wizard of oz#shadow creatures#jacques prevert#paul grimault#malus#robot#castle in the mist#horned boy#satyr

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The kingdom is being built higher and higher, but the stars will always be so far away."

🌌 ✨ 🎆

#le roi et l'oiseau#The King and the Mockingbird#La Bergère et le Ramoneur#La Bergere et le Ramoneur#my art#fanart#my fanart#paul grimault#french cinema

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Decline of Exhilaration: was meant to be a melancholic review of The Boy and The Heron, devolved into a rambling essay about the negative forces afflicting the world of traditional animation

Content warning: this text contains a negative review of Hayao Miyazaki's movie The Boy and the Heron, as well as an even more negative one of his previous movie The Wind Rises. I am aware that I'm in the minority on this one, and this isn't meant to dissuade anyone from watching either film. It is more about clarifying my own thoughts and feelings on why recent Miyazaki movies have not worked as well for me. This will be largely spoiler-free.

Tastes are diverse and subjective — work with me here; yes tastes most often come in normal distribution and are strongly correlated within specific demographics — doesn't matter, even if everyone in the world thought that blue eyes were the most beautiful, "blue eyes are the most beautiful" would still be a subjective statement — that is, "being the most beautiful" is not a property of blue eyes, it's property of how people feel when they look at blue eyes.

Tastes are diverse and subjective, and for some people, Miyazaki doesn't work.

I'm not one of them some people tho. I have been a fan of Miyazaki before I even knew Miyazaki was a person — no, really, I remember seeing bits of Future Boy Conan on tv when I was like 5, and being absolutely fascinated, even if it would be years until I properly discovered Miyazaki, and a few more years still until I realised that Future Boy Conan was from him. A few years after that first incident, I remember catching bits of a documentary showing excerpts of various animated films which at the time were mostly unknown in the west, and My Neighbor Totoro was in the lot — I was again captivated, but unaware of the name of Miyazaki, or even of the title of that movie, at the time — I was too young, not paying much attention to what was written on the screen, just looking at the pretty moving pictures.

I remember starting to becoming aware of Miyazaki as an entity at a time where the only movie of his that was avalaible in France was Porco Rosso. A bit later, My Neighbor Totoro was on tv, and after seeing it, I bought it on VHS — not from a regular store; it was sold in one those "collect them all" magazines, in this case each issue of the magazine had a different animated movie on VHS — I remember being very secretive about that purchase, I was in my first year of high school and didn't want anyone to know that I was watching movies "for little girls".

I remember getting someone on the internet (back when the internet was young and death was but a dream) to send me a burned cd-rom with a low-res bootleg copy of Vision of Escaflowne: the Movie fan-subbed in English (in which I was not yet fluent), by physical mail (downloading movies at the time was not a thing — connections were too slow) — and because there was still some room on the cd (you can imagine the quality of the encoding…), I requested that they add a copy of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind as well — it was the only way to see these movies at the time.

A bit later still, I remember dragging my father and sister to the theater to see Princess Mononoke, back when Miyazaki was not yet an established name in the west, and basically winning them over — one of the very rare times I managed to share something I loved with members of my family (or with anyone really), after which we often went to the theater to see both Miyazaki's new releases and his older movies finally getting to the big screen in the west. Each time was a great moment of joy, among the rare memories of my teenage years that I recall fondly.

I am not saying any of this to gate-keep — if you discovered Miyazaki in 2008 with Ponyo and call yourself a big fan, you're legit. I wouldn't even call myself the biggest Miyazaki fan outthere, but still, Miyazaki has been a very important figure in my life, and even if over time I have cooled down a bit on some of his earlier movies, Princess Mononoke and My Neighbor Totoro remain among my top favorite movies of all times (not just animated, movies period), and the manga version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is still one of most amazing and powerful fantasy series I have ever read.

Things started to shift around Howl's Moving Castle and Ponyo. I still eagerly went to see them in theater, I still enjoyed them a lot, but the spark wasn't quite there anymore, I didn't leave the theater with the same feeling of intense joy, with the same renewed love for life that I felt everytime I rewatched the older ones, and I never felt a strong urge to rewatch those new ones later on.

I didn't really notice that feeling at the time; it was a gradual shift, and was happening while my movie tastes were also rapidly changing. But the result was that when The Wind Rises came out in theaters in 2013, I found no desire to see it, and so I didn't. I told myself I would watch it later, on dvd or some such.

And so I ended up watching it… in 2022, 9 years after its release. Not a long time in itself, but when you considered the lengths I had gone to in the past to watch every Miyazaki movie as soon as possible… Still, I was optimistic; the movie had really good reviews, and in my head Miyazaki's name was still synonymous with "he never misses, the absolute legend!" (even tho I had already had a disappointing experience rewatching Castle in the Sky back to back after The King and the Mockingbird [remember that title for later], a comparison where the former pales a little — but at the time I had dismissed that experience as a fluke).

---

So I watched The Wind Rises… and didn't like it.

The problem wasn't the subject matter — I know that some have criticized the movie for its rather idealistic portrayal of Jiro Horikoshi, the designer of the Zero fighter planes, but for me this was just another movie in a tradition of Japanese cinema that, while condemning Japan's involvement in World War II, places the blame solely on the army's high command, absolving Japanese civilians, and sometimes even ordinary Japanese soldiers from any wrongdoing, and mostly emphasizes the suffering the war brought on Japanese people first and foremost, not so much denying as simply not adressing Japanese war crimes and the general hardship the war brought to other people.

In this respect the wind Rises is not different from The Burmese Harp (1956) or Dr. Akagi (1998); even movies like Grave of the Fireflies (1988) or Black Rain (1989), which are unambiguously anti-war and pretty critical of how Japanese society behaved during or right after World War II, still focus specifically on Japanese suffering — it's not an unproblematic narrative, but it's one I know my way around; an unfortunate but common blind spot of how Japanese people often see their own history, which you just have to expect if you're going to watch Japanese movies set during or in the aftermath of WWII (you can of course chose to skip those movies).

No, the problem with The Wind Rises is that I just found it boring. It felt like a meandering story that never really went anywhere, with characters that never felt more than surface-level, empty puppets existing only for the duration of the movie. This was compounded by an animation style that somehow felt both rigid and wobbly, coming very close to uncanny valley — it felt like Miyazaki didn't have a shred of empathy for the human characters in the movie and only cared about the planes, which were the only part that I enjoyed looking at.

I know how harsh this sounds, and how no one else seems to perceive the movie that way, but that's really what I felt: a huge, depressing disappointment — especially because I was apparently the only person who didn't like the film, adding a weird sense of alienation on top of it (to a degree — at this point I was already aware that my movie tastes had become quite weird).

A year passed, and The Boy and The Heron came out in theaters. I decided not to skip it, if only because it might well turn out to be Miyazaki's final film — I know he once again decided to postpone his retirement and start working on a new project, but Miyazaki is 82 and has not had the healthiest lifestyle, a whole 10 years have passed between The Wind Rises and The Boy and The Heron, and animation remains an extremely physically and mentally demanding job, so I have some serious doubts about whether we will really get another Miyazaki movie before his passing. The production of The Boy and the Heron was a lot more relaxed, Miyazaki setting no deadline and letting the animators work normal hours, declaring that the movie would be complete whenever it would be — a healthier approach for sure, but at the cost of more time, which Miyazaki doesn't have a lot of left.

---

So I went to see The Boy and The Heron, with pretty low expectations — not wanting to hate it, but severely tempering my expectations so as not to be too badly disappointed again.

The beginning was rather positive. The animation didn't have that uncanny quality that I had found in The Wind Rises, and there were even some interesting experimentations in stylicisation and visual metaphor, some stuff I hadn't seen before in a Miyazaki movie. As the movie settled into its story, I rather enjoyed the first half of it. I liked the slow burn mystery vibes, the cozy, detailed environments. I liked the portrayal of the main character as a boy trying very hard to hide his strong emotions and his grief, trying to appear calm, strong and well-behaved to others, while often acting impulsively and eratically when the his emotions crack thru the surface.

Even when the story shifted from magical realism into full on otherworldly fantasy, I was still on board, as the sense of mystery continued smoothly into the second part of the story. This wasn't amazing, this was a far cry from the extraordinary feelings that fill me when I watch Miyazaki's best stories, but it was fine, it worked.

Until it didn't.

I don't know exactly when the movie failed for me, but somewhere in the second half, the story lost its focus. It kept introducing more and more elements that had little relevance to the story, where never explored more than superficially, and felt like they were present solely because they were Classical Miyazaki Elements That Have To Be There In A Miyazaki Movie. This took the story from something that felt, if not wholly novel, at least somewhat different for Miyazaki, to a lesser, messier and less tight version of Spirited Away.

This kept going on for the last third/quarter of the movie, the story spinning in circles, the characters not making any progress — which highlighted the other flaws of the movie that I had so far overlooked: the characters who (outside of the protagonist) felt like lightly brushed caricatures with little substance; the inconsistency between characterisation and dialogue — several characters berate the protagonist for being "pretentious", even tho almost all he does is listen quietly, even to people disparaging him, and follow instructions given to him without protest.

At the end I was even noticing little flaws in the animation. The animation is good, but it's not great, or at least not as great as some previous Ghibli films — all the more baffling since The Boy and The Heron is reportedly the most expensive movie ever produced in Japan, and yet looked nowhere near as good as say, Makoto Shinkai's Suzume.

In a way, the last act of the movie felt — if you know of a less problematic way to put this, let me know — like an old person's ramblings: stories that don't go anywhere, full of tangential, unnecessary details that make no sense without a missing larger context. That made the whole thing crumble for me; these last thirty minutes, while they didn't outright make me hate the movie, pretty much destroyed what enjoyment of it I was having.

It's not that nothing happens anymore in the story, but it all feels ungrounded, floating, disconnected — emotionally disconnected that is, actions unfolding in front of my eyes yet without any tangible reality to them, as if the boundaries of fiction within which pattern recognition is enabled have broken, and I'm now just looking at… shapes.

I couldn't help but think of what a tragic contrast this was with My Neighbor Totoro, the best example of a movie where almost nothing is happening, and yet where your attention is being held the entire time, because of how perfect in its timing and details the storytelling is, because of how empathetically connected we are to the characters thru the extraordinarily accurate and yet amazingly simple exploration of their emotions and humanity. When I'm watching Totoro, I'm watching a human life, I'm watching the work of someone with profound understanding of human emotions. There was seemingly little left of that understanding in The Boy and the Heron.

And paradoxically, when the ending finally arrived, it felt sudden and abrupt — for a second I was certain there was going to be a continuation shot or something, but no, end credits. That's it then, huh? That's all that's left of Miyazaki's talent and storytelling skills.

Even the music turned out to be a disappointment, retrospectively — it didn't bother me during the movie, but once it was over, I could not remember a single melody, a single musical moment from it. I know there was music, I remember noticing some piano, but that's it, the music was otherwise just kinda there, and even as I was leaving the theater, all I could conjure up was instead the soundtrack from, again, My Neighbor Totoro.

---

I can easily rationalize this decline, find many material reasons for why it might have happened. It could be that the a large part of the Ghibli staff is now old — or dead; people aren't at the peak of their art anymore. Relatedly, a lot of the people who could say "no" to Miyazaki, or even more modestly give him advice he would actually listen to are no longer there. Still related is the apparent absence of a new talented generation at Ghibli — not thru any fault of their own, but rather because, between the shadow of Miyazaki looming over every Ghibli project, leaving little breathing room for other creators, and the apparent difficulty for the older generation to communicate and transmit their institutional knowledge, it seems that Ghibli has always been Miyazaki and Takahata's very personal medium, and not really a place for other creators to learn and thrive, and as the result the whole enterprise cannot but decline into old age and creep toward death along with its creators.

And yet, everyone else's reaction to the movie tells me that I am wrong. Reviews have been overwhemingly positive, and the movie has been doing numbers in theaters despite an intentional almost complete absence of promotion (at least initially). Why am I seemingly the only person for who this doesn't work anymore?

(Well, not quite the only one; I've definitely seen a few confused reactions among Miyazaki enjoyers, not least among them youtube essayist and Miyazaki expert STEVEM, whose opinion does seem to line up with mine.)

Is it that everyone else is too emotionally invested into Miyazaki's work, which has nurtured them since childhood, one of those rare pure and authentic things in our world, to admit to themselves that his movies do not work as well as they used to? That seems deeply unlikely — if only because of how self-flattering that explanation would be — implying that I alone am able to see past the nostalgia filter because I am so very smart, which, come on.

Is it that my tastes have radically changed? My tastes have radically changed, but I still consider Princess Mononoke and My Neighbor Totoro among the best movies ever made. There's a lot of movies I used to like as a kid/teenager/young adult that I am now completely indifferent to, but Miyazaki's early films are definitely not in that category.

Is it that I got wise to Miyazaki's tricks and no longer get the joy of discovery and surprise? But I had no idea where this movie was going for a good while, and knowing Princess Mononoke by heart doesn't prevent me from still enjoying it.

Is it that I am missing some context, some specifics of Japanese culture and beliefs that would help me make sense of the themes and plot of that movie? But I feel like I have developed a good "intuitive" understanding of Japanese culture; when I watch a Japanese movie, I don't understand everything I see, I don't know what every little detail mean, but I have a sense of how they fit together, I'm not surprised or confused by what I see, it doesn't feel out of place. I'm perfectly fine with Spirited Away and its many never-explained weird details, that doesn't impact my enjoyment.

Every explanation I come up with for the gap between my perception of Miyazaki's last two movies and that of the general public and critics fails short. I am really at a loss for a satisfying theory.

It seems that I have, then, to operate on the logic of alternate realities, having found myself (almost) alone in a reality where it is a fact that Miyazaki's directing abilities and the skills of the people who surround him have dramatically declined, (almost) everyone else living in a different reality where it is equally factual that Miyazaki is still at the top of his art and Ghibli is still the best animation studio in the world.

Here is my attempt to communicate what it's like to live in my reality, then:

More than any other form of creative endeavour, art or craft, the world of 2D animated movies appears to be cursed.

[note: I have an extremely materialistic, naturalistic and nihilistic view of reality, so I actually despise appeals to mysticism and magic as explanatory devices — even using them as metaphors displeases me, but by the point I noticed this is what I was doing here, the writing of this essay was too advanced, and taking the curse metaphor out would have required rewriting it entirely from the ground up, when I have already been working for weeks on it and I'm tired and it's not worth it, no one is going to read this anyway.]

---

Walt Disney started by making cartoon shorts (this will become relevant to Ghibli again at some point) for various companies, often struggling financially. In the late 20s, he was working for producer Charles Mintz at Universal Studio. Disney had ambition, he wanted to do more with the medium, and tried to negotiate with Mintz for higher budgets.

Instead, Mintz told him he was going to pay him less, and that Disney could do nothing about it because Mintz owned the rights to the characters Disney had created with his friend and collaborator Ub Iwerks. Mintz had also hired all of Disney's animators to work directly for him behind Disney's back. Mintz thought he had Disney cornered. Disney told him to get lost, and he quit, him and Iwerks founding a new studio in 1928 and creating the new character of Mickey Mouse as replacement for their lost IPs.

Under Disney's supervision, animators pushed the medium of cartoons to new technical ground, until the logical next step was to make a full feature length movie, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) — many thought this was an absurd idea and that the movie would flop badly. It was instead a huge success, but this would turn out to be the exception.

Many subsequent Disney films performed much more lukewarmly, while getting more expensive to make. There were enough successes to allow the Disney company to thrive for a while and establish itself as synonymous with quality animation. But with the advent of television, things started to get shaky — even Disney had to cut costs, simplify the animation and design, reuse old animations, with only middling returns at the box office. At some point Walt was outright told by his brother Roy that he should just shut down the studio completely and concentrate on the theme parks.

Things didn't really get better after Walt's death — if anything his spirit had strongly taken root in the company, and proceeded to fight back against attempts at modernization (sounds familiar?) A new generation of younger animators found themselves constantly opposed by the old guard; the making of each movie became a messy warzone where everyone was pulling in a different direction. Delays between movies got longer, productions got over budget while public reception continued to be milding.

Many prospective young talents (Don Bluth, Tim Burton, Brad Bird…) quit the company to try their luck elsewhere. When the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit finally got off the ground after nearly a decade of development hell, Steven Spielberg, who had been brought in as executive producer, had so little faith in Disney that the entire production was instead given to Richard Williams' London-based animation studio, with post-production handled by ILM, Disney merely distributing the movie (not even under their Disney brand, using their Touchstone label instead). Disney really looked like it was about to die.

But the old guard died off first, and the young animators had a chance to prove temselves, leading to the Disney Renaissance, a decade of box office and critical hits, once again pushing back the limits of animation.

Then things got rocky again. They started experimenting with 3D animated films, while the 2D ones rapidly became less profitable, and finally, in 2011, Disney abandonned 2D animated films, seemingly forever. Now Disney is a juggernaut, they own Pixar, Lucasfilm and Marvel, they produce completely devoid-of-personality, factory-churned, designed-by-comittee but highly profitable movies, and the curse of 2D animation is behind them. They survived, and it only cost them all of their talent and institutional knowledge.

Nonetheless, having pushed the limits of the medium for many decades, Disney inspired many others to try to follow in their footsteps. A lot of people suffered as a result.

---

Don Bluth joined Disney in 1971, a few years after Walt's death, working first as animator, then as animation director. He was part of that new generation of animators who tried to make Disney evolve toward a more mature approach of their stories, conflicting with older animators who wanted to keep things whimsical. This escalated until in 1979, during the production of The Fox and The Hound, Don Bluth resigned along with 11 other animators, and created his own animation studio.

Their first movie was The Secret of NIMH (1982), an amazing work of art that used many advanced animation techniques and required the work of 160 animators. It was a critical success… but had mediocre box office returns, forcing the studio to fill for bankrupcy.

Undeterred, Don Bluth went looking for other sources to finance his next projects, and found Steven Spielberg (it's 80s Hollywood, Spielberg is never really far), with who he produced An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). Both were huge success — An American Tail was the only Don Bluth film to beat Disney's competing movie (The Great Mouse Detective). This led Spielberg to form the new animation studio Amblimation, which produced 3 animated movies before getting folded into DreamWorks Animation, which itself alternated 2D and 3D animated films before entirely giving up on 2D animation after 2003, escaping the curse almost a decade before Disney.

Don Bluth however wasn't a fan of the collaboration and of the family-friendly edits Spielberg kept demanding to give the movies a wider appeal — as much as 10 minutes of footage were cut from The Land Before Time. He parted ways on the belief that he could do better on his own.

Using their own earnings from An American Tail and The Land Before Time, Don Bluth and his two close collaborators Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy produced two more movies: All Dogs Go To Heaven (1989), despite strange tonal shifts (it was a very dark story with violent character deaths and visions of literal hellfire — you know, for kids — interspersed with silly, surreal, acid-colored musical numbers), was a success. Rock-a-Doodle (1991) wasn't.

The early 90s were tough for Don Bluth: Rock-a-Doodle bombed so badly that, in order to avoid another brankrupcy, he had to sell the rights of all of his previous films — leading to the many direct-to-video low quality sequels that Don Bluth had no involvement with, while he struggled to finance his next movies, which all suffered from heavy executive-meddling and were critical and box office disappointments.

Then 20th Century Fox came to the rescue, signing Bluth a contract to produce animated movies for them, and staffing the newly created Fox Animation Studios with Don Bluth's own crew. Their condition was that the first movie had to be based on an existing property owned by Fox, leading to the creation of Anastasia (1997). The movie felt more like Disney than Don Bluth, but it was a huge success, the highest-grossing movie in all of Bluth's career. It gave him much more creative freedom for his next project, which was going to be something ambitious, something grand — finally Don Bluth was back!

And then Titan A.E. (2000) bombed so badly that it lead to the closure of Fox Animation and effectively ended Bluth's career, who never directed another movie after that.

Of course, he was still luckier than some.

---

Martin Rosen started his career as a literary agent then moved to become a movie producer. He eventually acquired the rights for an adaptation of Richard Adams's beloved childhood classic Watership Down, for which he also wrote the screenplay. Originally working only as producer, he took over as director after the original director left due to creative disagreements. It turned out to be a good move: the film, released in 1978, was a commercial and critical success, and went on to traumatize generations of British children.

Strong from this success, Rosen went on to adapt another book by Richard Adams: The Plague Dogs. The production was ambitious, bringing in several former Disney animators, included an up-and-coming Brad Bird and veteran Retta Scott. Unfortunately, the movie, after struggling to find distributors, flopped at the box office in 1982, a large part of the audience being turned off by the bleak story and graphic violence. Martin Rosen never directed another movie after this.

Of course, he was still luckier than some.

---

Paul Grimault, who had started making animated shorts in France in the 1930s, had a dream: creating a big animation studio that would be the French answer to Disney, and would produce feature-length animated films on a regular basis. He found financing, hired animators, and in collaboration with French poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert, started working in 1947 on a first project: an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Shepherdess And The Chimney-Sweep, in what was going to be the first feature-length animated film produced in France.

However, in spite of a crew of over a hundred people working on the movie, production ended up taking 5 years, with costs escalating to (adjusted for currency and inflation) 40 million dollars — a colossal budget in France just after WWII (of the 19 animated movies Walt Disney personally produced, only 3 had a higher budget than that). Paul Grimault was blamed for his perfectionism and was removed from the project, which was then hastily completed and released in 1953, in a version that Grimault and Prévert disowned, while the studio had to declare bankrupcy and close down.

While the movie had disappointing results, after a few years it found its way to an arthouse theater in Japan, where it was seen by two university students: Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who at the time were not even considering animation as a career. They were so transfixed by what they saw that they went to find the projectionist and convinced him to lend them the reel for one night, which they spent studying how the animation was made. This was one of several key films that convinced them to change their career and go into animation.

Meanwhile, back in France, Paul Grimault refused to let that story end there. In 1976, he bought back the rights of The Shepherdess And The Chimney-Sweep along with the original reels, and assembled a small team of young animators who worked to finally complete his vision of the movie, while making a number of additions, such as a new soundtrack composed by Wojciech Kilar. This version released in 1980 as The king and the Mockingbird, to high critical acclaim. Miyazaki and Takahata praised the new version, and Ghibli, as part of their Ghibli Museum Library, organized a theatrical release of the movie in Japan in 2006, followed by a dvd in 2007.

Paul Grimault was vindicated — but in the end, he only ever got to direct one feature-length animated film, when he dreamed of a career like that of Walt Disney.

Of course, he was still luckier than some.

---

Richard Williams was already working as an animator in the mid 50s, but his career consisted in directing tv commecials and short films (including an Academy Award winning adaptation of A Christmas Carol in 1971), with only one full length feature film, Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977).

But he had a dream, a project he had been slowly developing since 1964: The Thief and the Cobbler. Williams accepted to work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit for Disney and Spielberg mainly because they offered to finance his ongoing project to completion. After Roger Rabbit, Williams got a production deal with Warner Bros, and things looked good. But because of Williams's extreme perfectionism, things went slow, and eventually, in 1992, even tho the movie was almost complete, the production was taken away from Williams, and the movie was rushed into completion to be released ahead of Disney's Aladdin, under the name Arabian Knights, to generally bad reviews.

Williams didn't give up, he continued working on short films and tried to regain the rights to The Thief and the Cobbler to work off and on it, trying to finally bring his vision to completion.

Unfortunately, he died in 2019, and what should have been the work of his life was never completed. All that exists is a bootleg, incomplete cut put together by fans — they meant well and did their best, but the result is clearly not the finished movie Williams had in mind.

Of course, he was still luckier than some.

---

Yuri Norstein started working as an animator in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, for the studio Soyuzmultfilm. After participating in more than fifty short films, he was finally given a chance to direct, for which he developed a highly elaborate, personal style of cutout animation, with which he made the short films Hedgehod in the Fog (1975) and Tales of Tales (1979), both highly acclaimed internationally (including by Miyazaki). He then started working on his masterpiece, a feature-length animated adaptation of Nikolai Gogol's short story The Overcoat.

But because of his perfectionism, work advanced slowly (sensing a theme there). Too slowly for the taste of his employers, and in 1985 he was fired from Soyuzmultfilm. He was however able to keep the rights of his unfinished movie, and kept working to it on his own. But between his perfectionism, the difficulties of finding fundings, and the fact that he mostly just works alone with his wife, work has been very slow… In fact, as of writing these lines in 2023, Norstein is still working on The Overcoat, at the age of 82 (the same age as Miyazaki!), having completed just a third of the planned movie. Altho he claims that he currently has reliable funding and is working full time on completing the movie, the hopes of ever seeing the full film are not high.

---

Of course, all these men still got to direct at least short films and have their art recognized while they were alive. They are still more lucky than the nameless, countless individuals who tried to study and work in animation only to get burned out, never even getting a chance to prove themelves and show their creativity, ground to fine dust by one of the most demanding and least rewarding artistic professions, where even success is just the delaying of faillure — unless you stop playing first.

If you even survive the grind and get a chance to direct at all, if you aren't sabotaged by producers or by your own perfectionism, if your studio survives bankrupcies and your own decline, if it's not poisoned by your own shadow after your death, it will be only to lose its identity and abandon all that originally made it praised and loved.

There's no winning in animation. This is the curse.

---

---

Notes:

Most of this was written from memory based on stuff I've read sometimes more than a decade ago, using Wikipedia to fact-check names, dates and chronology.

Some sources I do remember drawing from include:

STEVEM's video-essays on animation in general and Miyazaki in particular

Defunctland's video-essay on the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Atrocity Guide's video-essay on Yuri Norstein

#the boy and the heron#movie review#essay#traditional animation#hayao miyazaki#studio ghibli#don bluth#yuri norstein#richard williams#the king and the mockingbird#martin rosen#watership down#paul grimault#once spending weeks writing an essay than no one will read instead of working on my fantasy novel#that's fine no one is going to read my novel either

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm amazed how much I fell in love with this Charl, even though he was the antagonist in this amazing cartoon (?).

and I'm horrified that so few people know about this piece of art

#The king and mockingbird#le roi et l'oiseau#french animation#Paul grimault#antagonist#villian#sketch#cartoon characters#artists on tumblr

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw the King and the Mockingbird and it made me think about how I want to approach stylisation of faces and people in animation, so I made a few sketches (using Peter Lorre’s face in several examples of course)

Also I have an idea for a scene in the film that’s based on recent events: people from Rijkswaterstaat patrolling the dikes with big yellow flags when the water was very high

#style exploration#drawing#sketchbook#sketch#concept art#style exercises#peter lorre#paul grimault#György Kovásnai

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

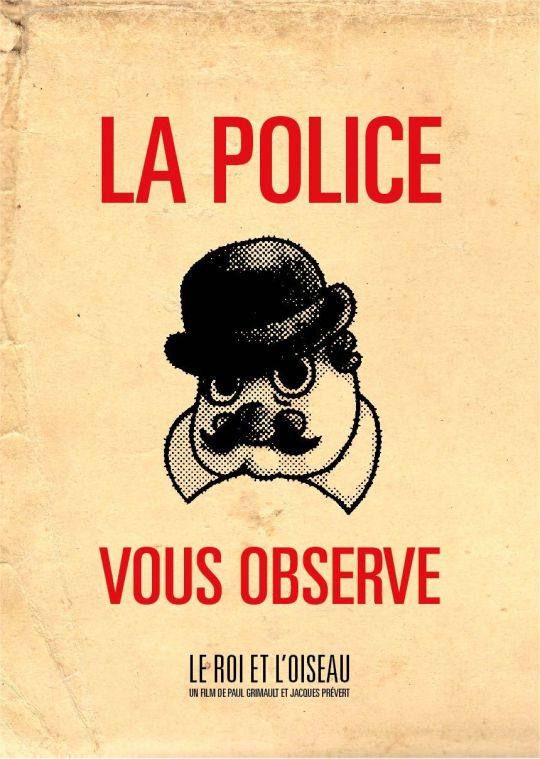

Paul Grimault & Jacques Prévert - Le roi et l’oiseau

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Le Roi et l'Oiseau (The King and the Mockingbird) by Paul Grimault.

The first animated surrealist film.

An animator's animated film. The King and the Mockingbird was at the forefront of animation as an art. Influenced Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

#Le Roi et l'Oiseau#The King and the Mockingbird#Paul Grimault#The King and Mister Bird#La Bergère et le Ramoneur#The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep#The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird#Hans Christian Andersen#Hayao Miyazaki#Isao Takahata#Jacques Prévert#Fumito Ueda

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#le roi et l oiseau#movieclips#cartoon movies#cartoon#french#paul grimault#jacques prevert#titan#machine#bird#bird cage#freedom#beauty#love#1980#the king and the mockingbird#movie#video#sound

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Table Tournante, Jacques Demy, Paul Grimault (1988)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Roi et L'Oiseau vs Le Château de Cagliostro (The King and the Mockingbird vs The Castle of Cagliostro)

Credits to: https://tinyurl.com/2ca7m6wb

#le roi et l'oiseau#the king and the mockingbird#french film#french animation#1980s movies#french cinema#paul grimault#jacques prévert#hayao miyazaki#studio ghibli#ghibli films#ghibli movie#castle of cagliostro#lupin the 3rd#1950s movies#lupin the third#isao takahata

95 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via Rene Laloux - Les Temps Morts - YouTube)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fumito Ueda was inspired by… The King and the Mockingbird (Le Roi et l'Oiseau).

These parts of the The King and the Mockingbird are *so* Shadow of the Colossus.

At the end, the giant robot engages a fan that blows away the entitled king. This is like Wander being sucked into the pool at the end of Shadow of the Colossus.

..............................................................

I love discovering these influences. Makes it just about fathomable how somebody could create something so magical.

#the king and the mockingbird#le roi et l'oiseau#the shepherdess and the chimney sweep#ico#fumito ueda#shadow of the colossus#hayao miyazaki#the castle of cagliostro#laputa#castle in the sky#hans christian andersen#jacques prevert#paul grimault#robot#shrine of worship

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'aventure de Canmom à Annecy - Vendredi 2: The Tunnel to Summer, the Exit of Goodbyes

It's almost a week since the day now but here's more Annecy writeups! I will be republishing this whole series in a very fancy filterable way on canmom.art soon, so look out for that!

Friday's second act was the new anime film The Tunnel to Summer, The Exit of Goodbyes (夏へのトンネル、さよならの出口 Natsu he Tonneru, Sayonara no Deguchi), a title which conveniently only uses kanji from the first ~10 levels of Wanikani so it's nice and easy to read. That said, this showing had both English and French subtitles, so I didn't need to lean on my Japanese knowledge this time. Here's a trailer...

youtube

This film seems to have been out in Japan for long enough that it's already available on nyaa (GJM are working on a sub), but this was actually my first time hearing about it. It was originally a light novel by Mei Hachimoku, then a manga, and now an anime film by Tomohisa Taguchi.

Taguchi has a pretty good track record as a director, although mostly stuff I've not seen. In fact the only of his works I've seen before is the original series Akudama Drive (2020), which is a very stylish scifi heist anime. He also directed the recent Bleach film, and the 2017 Kino's Journey TV anime, as well as a number of adaptations of the Persona games.

As seems to be customary for screenings at the Bonlieu Grand Salle, he and one of the producers (I regret that I didn't make a note of which of the three) came on stage before the film to comment a little. [That guy on the left - I'm not sure his name but he seems to be one of the main people running Annecy, since he introduced most of the films and carried out interviews at most of the Grand Salle screenings I went to.]

Taguchi remarked that most of his previous work has been action, so this more grounded romance film was a big change of pace. He spoke about wanting to capture the loneliness of the two main characters. The animation was carried out at Studio CLAP, a young studio whose previous work is Pompo the Cinephile, which we watched on Animation Night 123.

This film actually ended up winning the 'Paul Grimault Award', one of the three awards bestowed to feature films, which is named after a French animator who I presently mostly know from the bus stop by Cinema Pathé; at some point I gotta dig in more lmao.

So, with all that introduction... what sort of film was it? I went in expecting a solidly made summer movie in the Makoto Shinkai idiom... and that is indeed precisely what I got.

The story concerns two highschoolers, Kaoru (our main viewpoint character) and Anzu. Kaoru is a boy whose sister died when he was young, leading to his parents breaking up and his father falling into alcoholism. Since she was attempting to retrieve a beetle for him, he blames himself for the death - a sentiment shared by his father. Anzu meanwhile is a new transfer student who arrives at the school and immediately makes waves by acting standoffish towards the other students. She has aspirations to become a mangaka, following in the footsteps of her grandfather, but this has estranged her from the rest of her family who disapproved of his lack of success. So she severely doubts her own talent.

The pair meet on a rainy day waiting for a train that is delayed by hitting a deer, at which Kaoru lends Anzu his umbrella. This train stop becomes a recurring motif throughout the film, symbolising the evolution of their relationship. The other major element is a local legend of the 'Urashima Tunnel', which can grant wishes, at the price that time is drastically slowed down inside the tunnel, so that seconds inside the tunnel pass as hours outside. Kaoru discovers the tunnel is in fact real, and might give him a way to save his sister; Anzu follows him and the pair start researching the properties of the tunnel (e.g. its effect on phone communications), and draw up a plan to enter it and get what they want, even if it sends them thousands of years into the future.

Naturally they grow closer together and start to form a romantic relationship. Kaoru learns about Anzu's manga, and comes to the conclusion that she doesn't lack talent at all - and he also knows (somehow) that the tunnel is not capable of bestowing talent, only restoring things that were lost. So in the end (spoilers!) Kaoru enters the tunnel in secret without Anzu knowing. Eight years pass on the outside during which Anzu becomes a successful mangaka, still eaten by her highschool relationship; inside over a matter of minutes Kaoru finds his sister, and spends a little time with her, before realising that actually what he really needs is to be with Anzu, so he texts her and starts running back. They reunite near the entrance of the tunnel, smooch, and live happily ever after (even though Kaoru is still a high schooler and there's an eight year age gap lmao, this just straight up isn't even mentioned as a potential issue).

Generally I enjoyed the buildup a lot more than the final act. That this kind of movie centres on a heterosexual relationship is inevitable, but Anzu and Kaoru's hesitant relationship is genuine and sweet - the scene where Kaoru is reading Anzu's manga as she anxiously waits for his opinion is especially well observed. The pair's efforts, led by Anzu, to analyse the properties of the tunnel through experimentation is fun, since that's precisely what I would do if confronted with a magical tunnel of time dilation. That said, the central fantastical conceit, the time dilation tunnel, doesn't feel like an especially interesting metaphor.

Compared to the films of Makoto Shinkai, which visually and narratively it hews very close to (complete with the coloured highlights), the notable divergence is that the couple don't end up separated and do get their happy ending. Kaoru's decision to break their compact and leave Anzu alone outside the tunnel for eight years ultimately... just doesn't matter too much. He realises he needs to move on, says goodbye to his sister, and reunites with Anzu. I think it might be more interesting if Anzu actually ended up moving on and starting a different relationship and Kaoru had to face up to the fact that he has thrown away his one connection, but then I'm a miserable bitch who loves suffering lmao. Alternatively, I think it would be really cool if they actually did send themselves thousands of years into the future, although it would put this film into a very different genre.

In any case, the ending to this film ultimately left me a little cold. Yay, breeding pair got together.

Even so, it was absolutely an entertaining film; the environments are suitably beautiful, the animation is solid. Whether you'd enjoy it will probably depend how much you enjoy the "summer movie magical romance" subgenre. If you like Makoto Shinkai's movies, you'll probably like this one. If you hate Makoto Shinkai's movies, I expect you'd feel much the same about this one.

Speaking of Makoto Shinkai, I was a little surprised not to see Suzume in competition. But in general it seems pretty random which anime studios decide to submit their work to Annecy. Some studios like Science Saru have a pretty close relationship with the festival, others seem to ignore it entirely. (Perhaps it is a case of like, for smaller studios it's a valuable chance for promotion, but Makoto Shinkai is basically guaranteed a massive worldwide audience so he doesn't need to bother to come out to France?)

#l'aventure de canmom à annecy#film#anime#the tunnel to summer the exit of goodbyes#animation#annecy festival#annecy#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes