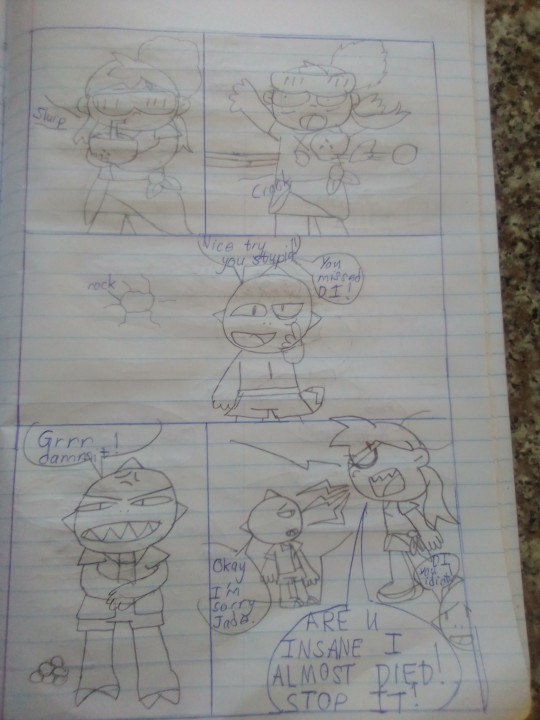

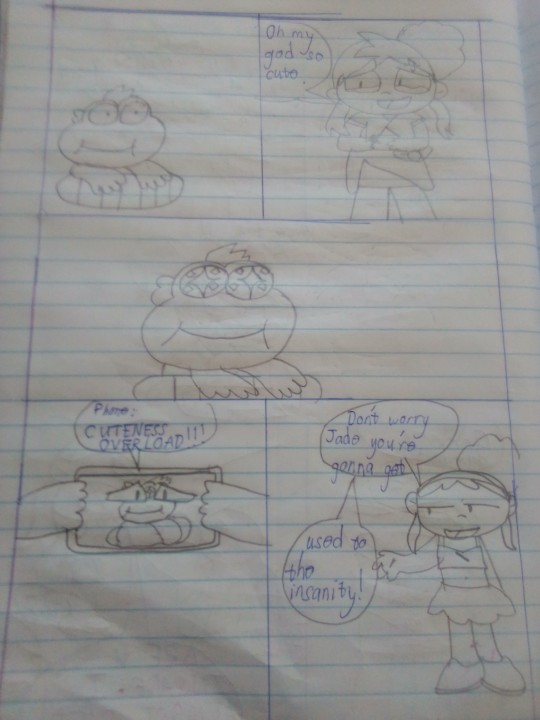

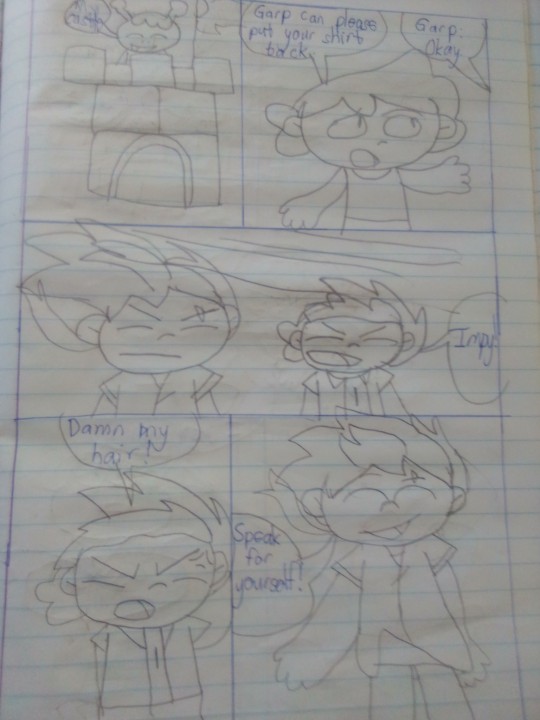

#msizi the human

Text

Allstars Madness S2 Ep9

@fanartalchemist

#jade#fanartalchemist#impy the imp#garp mayday#msizi the human#woss lay lou#croak the frog#demonic impy

2 notes

·

View notes

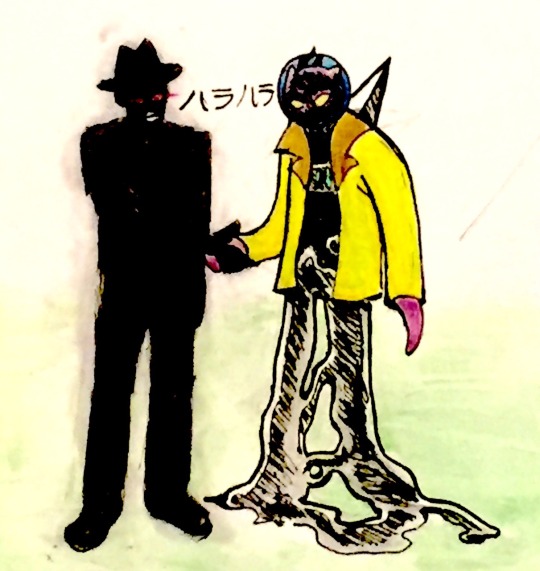

Text

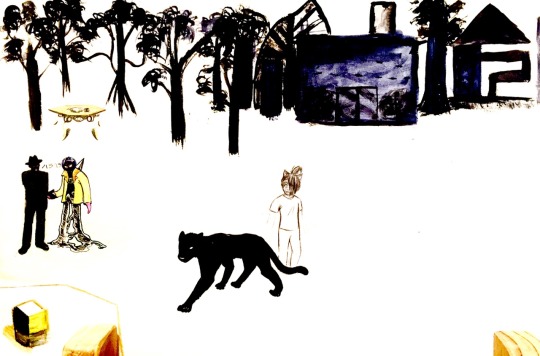

Peace Treaty

#black sun empire#hat man#arkon#walker#sea pig#msizi#panther#pantherfoos#dzvezda#human#my art#stickanime#painting#mixed media

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern

Walking into the Zanele Muholi exhibition at Tate Modern is like discovering another country.

In 2017 Muholi’s ongoing self-portrait series, Somnyama Ngonyama/Hail the Dark Lioness, was exhibited in London’s Autograph Gallery. In press reviews and posters on the tube that autumn, the images were unmissable and unmistakeable: stark black and white photographs of an impassive face crowned with Brillo pads or clothes pegs, festooned with vacuum cleaner hoses. At the time, Autograph wrote, the artist: “uses her body as a canvas to confront the politics of race and representation… Gazing defiantly at the camera, Muholi challenges the viewer’s perceptions while firmly asserting her cultural identity on her own terms: black, female, queer, African.”

Fast forward to 2020, and Tate Modern’s major Zanele Muholi exhibition. Visiting hours at the museum flicker in and out of existence as we navigate COVID lockdowns – now you can come! No, wait, sorry, you can’t. Try rebooking for a month’s time.

When I finally squeaked in, in early December, I expected more Dark Lionesses. I had a vague idea that Zanele Muholi was a bit like a South African Cindy Sherman.

I was wrong.

This exhibition shows the breadth of Muholi’s practice, of which the self-portraits are just one strand. The range and energy of the work is astounding. Especially given that in 2012 their studio was burgled and five years of work on hard drives was stolen.

Another mental adjustment: Muholi’s pronouns are they/them/theirs.

Born in Umlazi, South Africa, in 1972, at the height of Apartheid, Zanele’s father died when they were a baby and their mother, Bester, a domestic worker, had to leave her eight children for employment in a white household. Zanele was brought up by extended family. They started working as a hairdresser, then studied photography at Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, graduating in 2003, and going on to be awarded their MFA in Documentary Media from Ryerson University in Toronto in 2009.

On returning to South Africa they started to document the lives of the LGBTQI+ community.

Aftermath (2004)

The exhibition opens with a group of deceptively gentle images. In the first, Aftermath (2004), a torso is cropped from waist to knees, hands modestly clasped in front of Jockey shorts, a huge scar running down the person’s right leg almost like a piece of body art. In another, Ordeal (2003), hands wring out a cloth in an enamel basin of water placed on a floor. A third image shows a cropped, seated figure, again waist to thighs, hands folded in their lap, plastic hospital ties around their wrists. These pictures have a softness and beauty which completely belies the fact that their subjects are all survivors of sexual violence and “corrective rape”.

As the caption to the last picture, Hate crime survivor I, Case number (2004) explains, “Corrective rape is a term used to describe a hate crime in which a person is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The intended consequence of such acts is to enforce heterosexuality and gender conformity.” This horrific practice is by no means unique to South Africa, but the term seems to have originated there – feminist activist Bernedette Muthien used it during an interview with Human Rights Watch in 2001 – and its effects on the community resonate throughout this exhibition.

Ordeal (2003)

They don’t, however, dominate. While the exhibition starts by showing the evils of intolerance of gender nonconformity, Muholi goes on to reclaim, elevate and celebrate that same nonconformity.

With Being (2006 – ongoing) we move on to photographs of naked bodies entwined – again tightly cropped, again soft black and white, but now without outside interference. They are sensual, personal, and owned. A series of portraits of two female lovers, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta (2007) switches to colour and full figures. The couple sit entwined, laughing: they kiss, and bathe side by side standing in an enamel basin, in a warm, defiant echo of the scene in Ordeal (2003) across the room.

Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext.2, Lakeside, Johannesburg (2007)

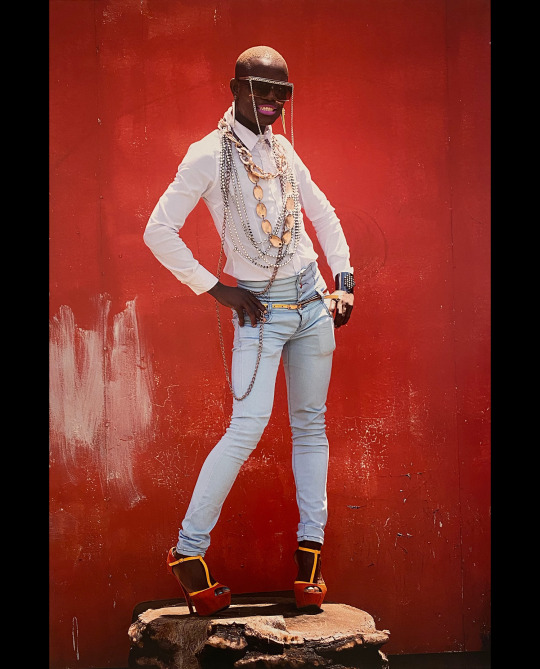

The series Brave Beauties, started in 2014, is “a series of portraits of trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people. Many of them are also beauty pageant contestants.” The queer beauty pageant is many things: a celebration – and redefinition – of beauty, a declaration of independence by contestants, a challenge to “heteronormative and white supremacist cultures,” and an attempt, as Muholi puts it, “to change mind-sets in the communities [the contestants] live in, the same communities where they are most likely to be harassed or worse.”

Melissa Mbambo, Durban, South Beach (2017). Melissa Mbambo is a trans woman and beauty queen, Miss Gay South Africa 2017

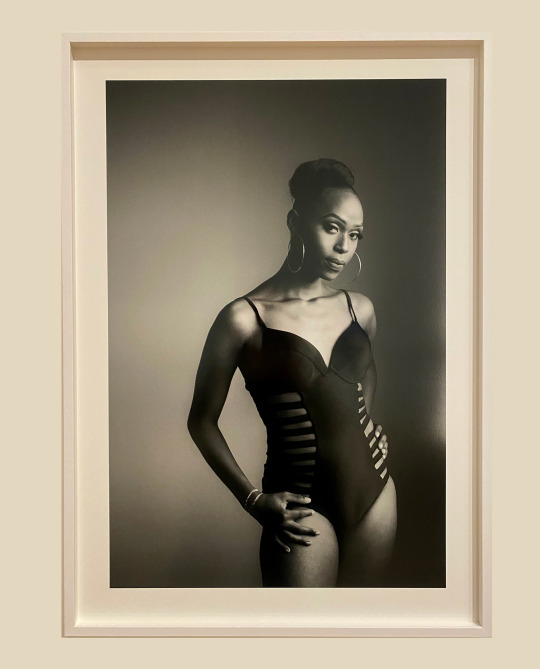

Roxy Msizi Dlamini, Parktown, Johannesburg (2018)

Akeelah Gwala, Durban (2020)

These portraits are made collaboratively, Muholi and the subjects choosing clothing, location and poses together. Some of them, like the picture of Roxy Msizi Dlamini (2018) have the quality of a classic glamorous studio shot. Others, like Akeeleh Gwala, Durban (2020), posing in a bikini against a scruffy brick wall in what seems to be a deserted brick alleyway, are a reminder of the vulnerability of the subject. Akeelah Gwala’s “Testimony” in the exhibition catalogue says: “I am 24 years old. I am a transgender woman. Growing up was very difficult because your parents think this is a boy… I was raped when I was 16 years old…” The rapist, a well-known pastor, threatened Akeelah’s family, forcing them out of their home. Akeelah refers to Muholi as “Sir Muholi” and says, “I have taken part in several beauty pageants. I perform because as a Brave Beauty, it is important to be visible and make others know about us and respect us as human beings.”

Miss Lesbian I-VII, Amsterdam (2009)

The theme of beauty pageants also features in the series of self-portraits Miss Lesbian I-VII, Amsterdam (2009), where Muholi casts themself as a beauty queen, an early identification with the wider community prefiguring Brave Beauties. The 2009 series brings together several of Muholi’s themes: the beauty pageant and the fashion/fashion magazine world; who gets to perform and who gets to watch; who gets to choose what beauty means? And, as an aside that may sound trivial but isn’t, kitchen utensils as headgear.

As the exhibition unfolds, we discover other projects. Muholi describes themselves as a visual activist, and they have a large network of collaborators, including the collective Inkanyiso (“Light” or “Illuminate” in isiZulu), a non-profit organisation focused on queer visual activism. We see images documenting marches and protests, weddings and funerals, and “After Tears” – gatherings held after burials to celebrate the life of the lost loved one.

Nathi Dlamini at the After Tears of Muntu Masombuka’s funeral, KwaThema, Springs, Johannesburg (2014)

Death is a constant presence in Muholi’s community and work. The largest space in this exhibition is given to Faces and Phases (2006 – ongoing), a collection of portraits – 500, and counting. The images “celebrate, commemorate and archive the lives of Black lesbians, transgender and gender non-conforming individuals.” People appear more than once. Some spots on the walls are empty, marking a portrait yet to be taken or a participant no longer there. One wall is dedicated to those who have passed away.

Not only is this a powerful and moving project, it’s an extraordinarily beautiful set of pictures. As are the last works in the show, the series that started in 2012: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness.

In this work, Muholi has darkened their skin and whitened their eyes, and composed the picture in the manner of a classical, perfectly-lit studio portrait, posing with found objects as “costume” – a footstool as a helmet, say. There is so much to unpick in these images – references to colonialism, Apartheid, to the politics of race and representation, to femininity and “women’s work”. Muholi presents us with a kaleidoscope of views of injustice, equal parts beautiful and brutal. The photographs were created in different parts of the world, at different times, combining what could almost be witty accessorising with intense cultural and political commentary.

Quinso, The Sails, Durban (2019)

The intellectual focus of every picture is slightly different. Zamile, KwaThema (2016) shows Muholi draped in a striped blanket, as used in South African prisons during Apartheid. In Quinso, The Sails, Durban (2019) Muholi’s hair is adorned with silvery Afro combs, a symbol of African and African diaspora cultural pride. In Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy (2015) their hair is stuffed with pens – a reference to the “pencil test” whereby, under Apartheid, if a pencil pushed into a person’s hair fell out they were “classified as white”.

Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy (2015)

As mentioned above, Muholi calls themselves a visual activist rather than an artist – though galleries, like Tate Modern, might beg to disagree. Walking through this exhibition, I came away with the impression that their work is on the intersection of art and documentary photography – but also that everything is documentary: everything is story telling, and bearing witness, and the place where “documenting the community” and “expressing oneself as an artist” is continually blurred.

Maybe it’s not just like discovering a new country: maybe Zanele Muholi is showing us a whole new world.

Zanele Muholi is at Tate Modern until May 31, 2021

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Termination of authorities at City of Tshwane resembles opportunism variance, states YCLSA

The Young Communist League of South Africa (YCLSA) in Tshwane has welcomed the dismissal of two “unqualified” officials in the office of City of Tshwane Mayor Stevens Mokgalapa.

The YCLSA, however, disapproves of the way in which the two officials – former mayoral spokesperson Samkelo Mgobozi and head of the private office of the mayor Stefan De Villiers – were fired by city manager Moeketsi Mosola after they were found not to meet recruitment requirements.

“Mosola sprung to action after Stevens Mokgalapa announced at his media briefing last week that he was initiating an investigation against Mosola for his role in the award of the controversial and corrupt GladAfrica contract.

“Mosola did this to show Mokgalapa who’s in charge,” district secretary Kgabo Morifi said in a statement on Monday.

Mokgalapa soon after his appointment as mayor of Tshwane announced that the City had cancelled the scandal-ridden GladAfrica contract.

GladAfrica scored a R12bn deal to provide the City with project management support, News24 earlier reported.

ALSO READ: New Tshwane mayor cancels controversial GladAfrica contract

The YCLSA says the move by the city manager “smacks of opportunism and inconsistency”.

The league claims that there are more individuals at the City of Tshwane who need to be shown the door.

The YCLSA names Landela Mahlati who it alleges was given employment contract extensions at the roads and transport department against the advice of human resources and supervisors.

“We demand that she also be shown the door. Mahlati was forced on the department to take care of the exorbitant GladAfrica invoices.

“Mahlati continues to act in a position where the appointment to fill the position was made,” Morifi explained.

The YCLSA further alleges that the City of Tshwane extended a contract with who they refer to as the “brains behind GladAfrica” – acting head of the mayor’s office Msizi Myeza.

‘Reign of terror’

“Myeza is currently sitting on his fifth or sixth extension. He, too, must be axed with immediate effect,” Morifi said.

He said Myeza and Mahlati should not receive special treatment because of “their proximity to Mokgalapa and Mosola”.

The YCLSA has also noted with concern Mosola’s “untrammelled power in running the City like his personal fiefdom” and further calls on the Auditor General’s office to temporarily deploy some of its personnel to conduct oversight on the City’s capital expenditure to avoid massive looting.

“Mosola is conducting a reign of terror among officials in the City of Tshwane.

“He suspends and dismisses officials at a whim when he has a plethora of misdemeanours against him. We will not relent until Mosola accounts for his litany of misdeeds,” Morifi concluded.

The post Termination of authorities at City of Tshwane resembles opportunism variance, states YCLSA appeared first on TheFeedPost.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2h5rP9h https://ift.tt/2TulVmM

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

It's One Thing To Be Buried Alive, But To Be Left In A Mortuary Freezer For Days?

New Post has been published on https://kidsviral.info/its-one-thing-to-be-buried-alive-but-to-be-left-in-a-mortuary-freezer-for-days/

It's One Thing To Be Buried Alive, But To Be Left In A Mortuary Freezer For Days?

It’s the one phone call you hope you never have to answer.

Your son or daughter was involved in a car accident and is in the hospital fighting for their life. After doctors have tried everything they can, your baby is pronounced dead and you are forced to come to terms with the fact that you have to start planning their funeral.

But doctors are humans, too, and can therefore make mistakes as well. It’s a scary realization that every once in awhile, someone is pronounced dead before they’ve given up the fight. This unfortunate medical oversight recently costed one man his life.

Msizi Mkhize was walking home late at night when he was struck by an oncoming car. When paramedics arrived on the scene, the young South African man was pronounced dead.

Flickr / Simon Law Follow

After the man spent more than two days in a mortuary freezer, his family came to collect his body for the funeral only to make a horrifying discovery — their son still had a pulse.

Getty Images

Emergency personnel rushed Mkhize to Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Hospital where doctors and nurses tried to revive the very man that was previously pronounced dead. Unfortunately, the medical staff was unable to revive him and he died just five hours later.

Flickr / MilitaryHealth

Read more: http://www.viralnova.com/freezing-to-death/

0 notes

Text

#MyRadioPeople : Metro FM's Msizi Shembe

#MyRadioPeople: @MetroFM's Msizi Shembe

This week’s feature is rather inspirational, I am really humbled to have a down-to-earth human being, Msizi Shembe on this blog today. Having experienced working with him when I was still with Vuma FM and seeing his work ethic, I didn’t even have to think twice to ask him to share his radio journey with me and you. Enjoy!

Why radio? I guess its about music and the love to talk with people…

View On WordPress

0 notes