#morning (solam)

Text

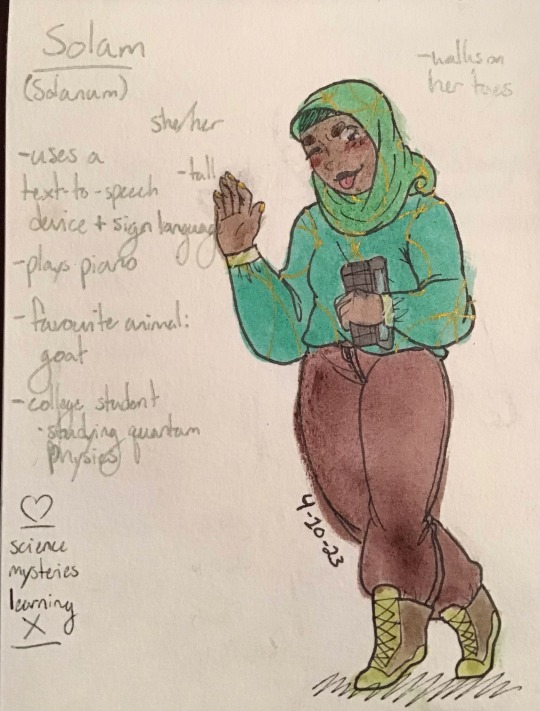

Meet Solam! She’s a quantum physics major who joins Wild Ventures after her classmate Gab (Gabbro) talks her into it. She’s excited and ready for adventure!

Some Facts:

Solam uses a text-to-speech device as well as sign language; I’m not sure if she’s mute or has trouble speaking or something else, but she gets by well enough.

She plays piano! She brought a keyboard from home and set it up in her dorm room as soon as she could.

Her favourite animals are goats :) Some of her other favourite things are science, mysteries, and learning.

Solam is fairly tall and has a habit of walking on her toes.

#my art#outer wilds au#morning; 14.3 billion years later#outer wilds solanum#not me delaying posting this because i was trying to figure out#things she does or doesn’t like#which i *still* have nothing for btw#girl what don’t you like#also! her hijab is styled after the nomai masks#with the back mirroring the oxygen tank#her outfit as a whole is supposed to look like her suit#i’ll do a post with the whole gang at some point#morning (solam)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mvelo Mahlangu in NYC, Day 14

Today I woke up to SNOW! It was snowing and everything looked so beautiful! I did not think that I would be able to see a snow day during my time here. It was really cold, but felt magical. One thing I did think about was where do all the homeless people go when its this cold and this type of weather? Today on the list was heading to Queens to sit in on an AA meeting. After hoping into the train, I started researching more on where the AA meeting was going to be held because I was worried about the weather. I saw that it said “outdoor” for the meeting venue and I worried if it was still going to happen. Nonetheless I thought to continue to at least try and go to the park even if it means I just see the park. However, halfway through my train ride, I got a notification from Nia letting me know it was cancelled. Along with the AA meeting being cancelled, my next activity was also cancelled. Meeting with Vanessa, my last activity, was also subject to change. So I essentially had an impromptu free morning. Since it was quite cold, I decided to rather head back to the apartment.

I later got a message from Nia letting me know that Vanessa was still up to meet with me and that I could meet her in Brooklyn right around the corner from Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). At this point, I still didn’t realise who Vanessa was, so wondered what we would be talking about. When we finally met, she mentioned Solam's (the wonderful person who nominated me for this program) name. And it clicked! Months prior to me arriving in NY, Solam had shared his experience with me, of studying in New York and meeting Vanessa while she worked at a restaurant. They hit it off and became fast friends. They reconnected last year when Solam had gone to New York, and during the time they met, Vanessa had mentioned to Solam that she needed to go to work however he could tag along as there was an exhibition on apartheid happening where she would be working. This exhibition space turned out to be Apexart.

When it clicked, I wanted to share my appreciation as she was also a part of the process of me being here. As we walked over to a coffee shop, we stopped by a Ballet studio where she would sometimes go to as she was a dancer. Once we got to the cafe, we spoke for a while. She told me about her background and her connection to Steven, Nancy and Apexart. I really really enjoyed speaking with Vanessa and connecting with her. Ah wow! So much gratitude. I was going to share this with Solam and send him a photo that Vanessa and I took together.

0 notes

Text

Our Food for the Many Rainy Days Ahead

Goa’s monsoon season has long necessitated the practice of purumenth, or stocking up. Today, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s a new kind of lifesaver.

We were the crow chasers.

Armed with rolled-up newspapers and sticks, we three siblings waited on the balcão (balcony) guarding the choris (Goan sausages) that were draped over a bamboo rod perched above the ground. Inside, the family sat on the floor mixing pork with local toddy vinegar, chiles, and spices, stuffing it into a casing of pigs’ intestines. A cotton thread tied off links, forming a meaty necklace dripping with fat and staining everything red.

These meat necklaces were our assignment, and they attracted crows by the dozen. The sausages hovered over freshly sourced chiles from different villages, solam (kokum), tamarind, mangoes, and fish, all spread on newspaper or mats woven from coconut palms. The salty aromas, mingled with the afternoon heat, proved irresistible to the birds. Fighting them off on hot summer days was our main source of entertainment during this long and tedious process, and we fought bravely.

These items, after all, were important — this was our purumenth, our food for the many rainy days ahead.

Purumenth (sometimes spelled purument or purmenth) is the local Konkani corruption of the Portuguese word provimento or provisão, meaning provisions. It is, most simply, the practice of stocking up for times when food is scarce.

Goa is a small state on India’s west coast. Ruled by the Portuguese from around 1510 until 1961, Goa today is known for being a popular travel destination thanks to its distinct cuisine, cultural diversity, cheap alcohol (tax rates on booze vary throughout India, and Goa has among the lowest), and beachy, laid-back life compared to cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

It’s also known for monsoons.

India’s monsoon season follows the hot, dry summer months of April and May and it lasts from June until September. The rain is fickle, alternating between light drizzles and heavy downpours that cause destructive flooding, limiting transportation and the mobility of goods and people — and, historically, making fresh ingredients like produce, meat, and fish scarce.

“Until a few decades back, provisions for the rains had to be gathered well in advance as the rains were unpredictable, weather forecasting was unknown, and refrigeration facilities non-existent,” writes historian Fátima da Silva Gracias in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through.”

For decades, my family — like many others in villages across the state — would stock up for the harsh and volatile monsoon. Preparations began early, from mid-February onward. April and May, then, were months of abundance, of cheap goods and busyness. Food was procured, cleaned, sun-dried, pickled, and stored.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through,” says archaeologist and culinary anthropologist Kurush F. Dalal. “Everybody stocked things on a yearly basis — masala, dals and ghee, pickles, dry fish, salt, and pappad. It wasn’t frugality, but systematic planning to ensure the larder was always full.”

Everything had to be ready by mid-May in case of early showers. Those who were unable to prep in time by themselves could stock up at Purumentachem Fests held at the end of May and early June. These fairs were linked to the annual church feasts in the cities of Margao and Mapusa, which, since they occurred around time the monsoons began to sweep in, sold a variety of purumenth staples for last-minute shoppers.

For the most part, purumenth is the stuff of culinary history. Over the last few decades, the arrival of refrigerators to store produce, the availability of fresh goods throughout the monsoons, and increased mobility between villages and cities have made stocking up less crucial. Purumenth fairs still occur annually, and locals still stock up on dried fish, rice, vinegar and pickles, but lately they’ve been less driven by necessity than nostalgia — “preparing” less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

But then COVID hit. On March 24, Goa, like the rest of India, went into a government-mandated lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. The announcement was a surprise and ill-planned, leaving people with no time to prepare. In the initial days, people weren’t allowed to leave their homes; shops and markets were shuttered, and there was no public transportation. In many places, people started rationing meals as supplies started to run out. For the first time in a long time, food was hard to come by.

In the villages, elders nodded their heads wisely. It wasn’t the monsoon season yet, but they knew how to deal with this enforced isolation. They had been storing provisions for years and had a diminished but stocked larder. It was our younger generation that struggled, spoiled by abundance of choice and instant gratification, and living in homes where space is too premium to be utilized for storing goods.

“Our ancestors were smart enough to live by the seasons. But we’ve become greedy, and our demands have exceeded our supply,” says Avinash Martins, chef and owner of Cavatina Cucina. “Had we to follow our ancestral cycle, we wouldn’t have taken our food for granted.”

In the olden days, Goan kitchens had a cow dung-smattered floor and an earthen stove. On a bamboo rod placed high across the kitchen hung local white onions and sausages — the smoke from the fireplace kept the insects away — and most houses had a designated storage area, a secluded corner, the space under the bed or a dark room.

This space, while not exactly photogenic, offered a snapshot of summer bounty like cheap fresh fish, mangoes, jackfruit, chiles, and cashews. Here, too, lay all the dried, salted, and cured produce. There was kokum, tamarind balls, whole spices, masalas, and bhornis (porcelain jars) with pickles like chepne tor (flattened raw mangoes in brine). Some families had mitantulem mas — salted pork drained of its water via heavy weights and dried into a jerky of sorts. There was coconut oil and vinegar made from the toddy extracted from the coconut palms. Summer fruits like jackfruit and mangoes — including the seeds — were peeled, sliced, and dried for use in curries.

My family still lives in a small village in the north of Goa, in an old Indo-Portuguese house. Back in the 1930s and ’40s, the building had a separate room dedicated to rice. The bhathachim kudd (paddy room) was in the center of the house with no direct access to sunlight, keeping it cool and dark, and had a roughly hewn bamboo structure filled with paddy — rice with husk — from our fields.

“Preparing” has become less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

“We dried the paddy in the sun to prevent insects from eating it, and parboiled it in a bhann [a big copper pot],” says Maryanne Lobo, an Ayurvedic doctor in Goa whose family also had a bhathachim kudd. “Once boiled, we took it to the mill to remove the bran, and stored the rice in a dhond [a barrel-like container].”

Lobo learned about purumenth from her maternal aunt. “She would store jackfruit seeds in a hole dug into the floor. She used the mud from an ant hill to create a well and covered the top with cow dung mixture. This kept the seeds dry and free from insects.” Dried jackfruit seeds were cooked like a vegetable, or added to curries.

Like her aunt, Lobo still stocks up religiously every summer. She doesn’t have a storeroom anymore, so the paddy is dried in her balcony, and she stores her jackfruit seeds in sand. The traditional jars have given way to plastic bottles, and provisions are stocked beneath beds — but still, she says “purumenth was a lifesaver” during the lockdown.

There’s something overwhelming and intoxicating about the smell of dried fish — fierce, pungent, and fermenting. Traditionally, in the monsoon months fishermen could not venture out into the choppy sea, so good fish was scarce. Locally caught fish from rivers and ponds was limited and expensive. People, then, preferred eating kharem (salted fish).

Goa’s typical dried fish stock includes the common mackerel, salted and dried and pickled to become a para with vinegar and masalas; dried shrimp; and prawns — pickled into a tangy molho or balchao, or dried. In the monsoon, this fish forms the accompaniments to a simple lunch of rice and plain curry, or to the mid-morning meal of pez (rice gruel). Dried shrimp becomes kismur — a dry salad made with coconut and tamarind, for which the prawns are roasted over a flame with coconut oil and the para is fried and roasted.

Fish was high on Marius Fernandes’s summer prep this year. Known as Goa’s “Festival Man” — responsible for conducting more than 40 cultural festivals in the region — Fernandes has dedicated his life to promoting the traditional Goan way of life. On lockdown in the small island village of Divar, he spent the summer doing prep under the guidance of his 88-year-old mother, Anna. The family dried and pickled prawns and mackerel, seeds, ripe and raw mangoes, jackfruit, pineapples, and tomatoes. “The situation with regards to sourcing fresh food is only going to get worse in this current situation,” says Fernandes, who has spent much of the last few months in the family garden. “We have to start thinking about growing our own food.”

Like Fernandes, the few who never stopped practicing purumenth are eloquent about its benefits. And those who are rediscovering it now, in response to COVID-19 shortages, are finding that it fits well into the modern ethos surrounding eating. “This is the new gourmet: food that is harvested locally, is seasonal, organic, grown in small batches, with a zero-carbon footprint,” says Cavatina Cucina’s Martins, who became more conscious about his food back in 2018 when the toxic chemical formalin was found in fish and led to a scare in Goa. Today he makes and stores pickles, fish, chiles, and salt.

“Because of the lockdown, we again know about all the wonderful produce available here,” says Fernandes. “Earlier, these would go to markets and supermarkets. Now, we are getting first pick of this locally grown, organic produce.”

Today, my larder in Mumbai has a few traces of purumenth: some salted shrimp and a pack of sausages. There have always been sausages in my kitchen, my way of connecting back to my home in Goa. There’s no need to fight off any crows, though — just my dog, who is equally fascinated by fragrant links of choris.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist from India who enjoys writing about food and its ties to communities, her Goan heritage, and other things that make her happy. Roanna Fernandes is an illustrator from Mumbai.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2BRZe54

https://ift.tt/3ftPNq9

Goa’s monsoon season has long necessitated the practice of purumenth, or stocking up. Today, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s a new kind of lifesaver.

We were the crow chasers.

Armed with rolled-up newspapers and sticks, we three siblings waited on the balcão (balcony) guarding the choris (Goan sausages) that were draped over a bamboo rod perched above the ground. Inside, the family sat on the floor mixing pork with local toddy vinegar, chiles, and spices, stuffing it into a casing of pigs’ intestines. A cotton thread tied off links, forming a meaty necklace dripping with fat and staining everything red.

These meat necklaces were our assignment, and they attracted crows by the dozen. The sausages hovered over freshly sourced chiles from different villages, solam (kokum), tamarind, mangoes, and fish, all spread on newspaper or mats woven from coconut palms. The salty aromas, mingled with the afternoon heat, proved irresistible to the birds. Fighting them off on hot summer days was our main source of entertainment during this long and tedious process, and we fought bravely.

These items, after all, were important — this was our purumenth, our food for the many rainy days ahead.

Purumenth (sometimes spelled purument or purmenth) is the local Konkani corruption of the Portuguese word provimento or provisão, meaning provisions. It is, most simply, the practice of stocking up for times when food is scarce.

Goa is a small state on India’s west coast. Ruled by the Portuguese from around 1510 until 1961, Goa today is known for being a popular travel destination thanks to its distinct cuisine, cultural diversity, cheap alcohol (tax rates on booze vary throughout India, and Goa has among the lowest), and beachy, laid-back life compared to cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

It’s also known for monsoons.

India’s monsoon season follows the hot, dry summer months of April and May and it lasts from June until September. The rain is fickle, alternating between light drizzles and heavy downpours that cause destructive flooding, limiting transportation and the mobility of goods and people — and, historically, making fresh ingredients like produce, meat, and fish scarce.

“Until a few decades back, provisions for the rains had to be gathered well in advance as the rains were unpredictable, weather forecasting was unknown, and refrigeration facilities non-existent,” writes historian Fátima da Silva Gracias in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through.”

For decades, my family — like many others in villages across the state — would stock up for the harsh and volatile monsoon. Preparations began early, from mid-February onward. April and May, then, were months of abundance, of cheap goods and busyness. Food was procured, cleaned, sun-dried, pickled, and stored.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through,” says archaeologist and culinary anthropologist Kurush F. Dalal. “Everybody stocked things on a yearly basis — masala, dals and ghee, pickles, dry fish, salt, and pappad. It wasn’t frugality, but systematic planning to ensure the larder was always full.”

Everything had to be ready by mid-May in case of early showers. Those who were unable to prep in time by themselves could stock up at Purumentachem Fests held at the end of May and early June. These fairs were linked to the annual church feasts in the cities of Margao and Mapusa, which, since they occurred around time the monsoons began to sweep in, sold a variety of purumenth staples for last-minute shoppers.

For the most part, purumenth is the stuff of culinary history. Over the last few decades, the arrival of refrigerators to store produce, the availability of fresh goods throughout the monsoons, and increased mobility between villages and cities have made stocking up less crucial. Purumenth fairs still occur annually, and locals still stock up on dried fish, rice, vinegar and pickles, but lately they’ve been less driven by necessity than nostalgia — “preparing” less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

But then COVID hit. On March 24, Goa, like the rest of India, went into a government-mandated lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. The announcement was a surprise and ill-planned, leaving people with no time to prepare. In the initial days, people weren’t allowed to leave their homes; shops and markets were shuttered, and there was no public transportation. In many places, people started rationing meals as supplies started to run out. For the first time in a long time, food was hard to come by.

In the villages, elders nodded their heads wisely. It wasn’t the monsoon season yet, but they knew how to deal with this enforced isolation. They had been storing provisions for years and had a diminished but stocked larder. It was our younger generation that struggled, spoiled by abundance of choice and instant gratification, and living in homes where space is too premium to be utilized for storing goods.

“Our ancestors were smart enough to live by the seasons. But we’ve become greedy, and our demands have exceeded our supply,” says Avinash Martins, chef and owner of Cavatina Cucina. “Had we to follow our ancestral cycle, we wouldn’t have taken our food for granted.”

In the olden days, Goan kitchens had a cow dung-smattered floor and an earthen stove. On a bamboo rod placed high across the kitchen hung local white onions and sausages — the smoke from the fireplace kept the insects away — and most houses had a designated storage area, a secluded corner, the space under the bed or a dark room.

This space, while not exactly photogenic, offered a snapshot of summer bounty like cheap fresh fish, mangoes, jackfruit, chiles, and cashews. Here, too, lay all the dried, salted, and cured produce. There was kokum, tamarind balls, whole spices, masalas, and bhornis (porcelain jars) with pickles like chepne tor (flattened raw mangoes in brine). Some families had mitantulem mas — salted pork drained of its water via heavy weights and dried into a jerky of sorts. There was coconut oil and vinegar made from the toddy extracted from the coconut palms. Summer fruits like jackfruit and mangoes — including the seeds — were peeled, sliced, and dried for use in curries.

My family still lives in a small village in the north of Goa, in an old Indo-Portuguese house. Back in the 1930s and ’40s, the building had a separate room dedicated to rice. The bhathachim kudd (paddy room) was in the center of the house with no direct access to sunlight, keeping it cool and dark, and had a roughly hewn bamboo structure filled with paddy — rice with husk — from our fields.

“Preparing” has become less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

“We dried the paddy in the sun to prevent insects from eating it, and parboiled it in a bhann [a big copper pot],” says Maryanne Lobo, an Ayurvedic doctor in Goa whose family also had a bhathachim kudd. “Once boiled, we took it to the mill to remove the bran, and stored the rice in a dhond [a barrel-like container].”

Lobo learned about purumenth from her maternal aunt. “She would store jackfruit seeds in a hole dug into the floor. She used the mud from an ant hill to create a well and covered the top with cow dung mixture. This kept the seeds dry and free from insects.” Dried jackfruit seeds were cooked like a vegetable, or added to curries.

Like her aunt, Lobo still stocks up religiously every summer. She doesn’t have a storeroom anymore, so the paddy is dried in her balcony, and she stores her jackfruit seeds in sand. The traditional jars have given way to plastic bottles, and provisions are stocked beneath beds — but still, she says “purumenth was a lifesaver” during the lockdown.

There’s something overwhelming and intoxicating about the smell of dried fish — fierce, pungent, and fermenting. Traditionally, in the monsoon months fishermen could not venture out into the choppy sea, so good fish was scarce. Locally caught fish from rivers and ponds was limited and expensive. People, then, preferred eating kharem (salted fish).

Goa’s typical dried fish stock includes the common mackerel, salted and dried and pickled to become a para with vinegar and masalas; dried shrimp; and prawns — pickled into a tangy molho or balchao, or dried. In the monsoon, this fish forms the accompaniments to a simple lunch of rice and plain curry, or to the mid-morning meal of pez (rice gruel). Dried shrimp becomes kismur — a dry salad made with coconut and tamarind, for which the prawns are roasted over a flame with coconut oil and the para is fried and roasted.

Fish was high on Marius Fernandes’s summer prep this year. Known as Goa’s “Festival Man” — responsible for conducting more than 40 cultural festivals in the region — Fernandes has dedicated his life to promoting the traditional Goan way of life. On lockdown in the small island village of Divar, he spent the summer doing prep under the guidance of his 88-year-old mother, Anna. The family dried and pickled prawns and mackerel, seeds, ripe and raw mangoes, jackfruit, pineapples, and tomatoes. “The situation with regards to sourcing fresh food is only going to get worse in this current situation,” says Fernandes, who has spent much of the last few months in the family garden. “We have to start thinking about growing our own food.”

Like Fernandes, the few who never stopped practicing purumenth are eloquent about its benefits. And those who are rediscovering it now, in response to COVID-19 shortages, are finding that it fits well into the modern ethos surrounding eating. “This is the new gourmet: food that is harvested locally, is seasonal, organic, grown in small batches, with a zero-carbon footprint,” says Cavatina Cucina’s Martins, who became more conscious about his food back in 2018 when the toxic chemical formalin was found in fish and led to a scare in Goa. Today he makes and stores pickles, fish, chiles, and salt.

“Because of the lockdown, we again know about all the wonderful produce available here,” says Fernandes. “Earlier, these would go to markets and supermarkets. Now, we are getting first pick of this locally grown, organic produce.”

Today, my larder in Mumbai has a few traces of purumenth: some salted shrimp and a pack of sausages. There have always been sausages in my kitchen, my way of connecting back to my home in Goa. There’s no need to fight off any crows, though — just my dog, who is equally fascinated by fragrant links of choris.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist from India who enjoys writing about food and its ties to communities, her Goan heritage, and other things that make her happy. Roanna Fernandes is an illustrator from Mumbai.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2BRZe54

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2D6Q5Xe

0 notes

Text

Day 129: Ardbeg and Lagavulin

For our first day on Islay, we'd booked tours and tastings at our favorite distilleries--Ardbeg (mine) and Lagavulin (my dad's). At least, those are the distilleries we would have said were our favorites when we arrived. We have since come to the enlightened conclusion that all whiskies are beautiful and that it's unfair to play favorites.

And our first visit would also be our most interesting and unconventional one--the Ardbeg bog walk. We'd get to hike along the stream that feeds Ardbeg up into the peat bogs that gives Islay whiskies their distinctive smoky, maritime flavors.

There are three distilleries on the south coast of Islay. Laphroaig is about one mile east of Port Ellen, Lagavulin is about a mile beyond Laphroaig, and Ardbeg is about past Lagavulin.

Knowing we had a healthy three-mile hike ahead of us, we made sure to leave with plenty of time to spare. But we kept stopping so much to gawk and take pictures of the beautiful coastal scenery that we still found ourselves having to rush the last twenty minutes or so to get there in time.

It was still mid-morning, and already the summer heat was beating down on us. But we made it.

After checking in, we had just enough time to use the facilities, browse the gift shop, and take in the ambiance. We were each given a drawstring swag bag with a homemade sandwich lunch and a mini tasting glass with Ardbeg 2018 printed on the side.

Our tour group included a native Scotsman, a young Asian family with a baby in tow, and a friendly Polish couple that Jessica enjoyed extracting a bit of conversation from.

Our guide Dougie was a semi-retired Adrbeg employee who was actually born in Ardbeg when it was still a hamlet where other people lived. He even showed us a picture of his house and pointed out the patch of land where it once stood. Modernization happens even here--in its own way and time--and many of the small crofts and hamlets that dot the island have been abandoned the larger villages like Port Ellen, Bowmore, and Port Charlotte.

We had been warned over and over again about our shoes in the days and minutes leading up to the walk. We heard horror stories of boots lost to the ages in inscrutable muck of Islay's murky fens. We were even offered galoshes (or "Wellies" as they're called in Britain) to borrow on multiple occasions. We all declined, partly out of awkwardness and partly out of confidence born of the beating summer sun still hounding us on our journey.

Our confidence was rewarded. For possibly the first time in years, Islay had gone so long without rain that the peat was practically dry to the touch. We barely got the soles of our shoes dirty.

As Dougie lead us along the Ardbeg Burn--the creek that feeds the distillery from its source at Loch Uigeadail--he let slip that we wouldn't be tasting just any whiskies. The way he saw it, we could taste the Ardbeg core range anytime we wanted. But he had the power to give us something truly special. He had the key to the VIP whisky cabinet.

As we hiked into the hills and enjoyed the spectacular scenery, we occasionally stopped to sip a wee dram and hear its story:

Ardbeg Still Young: After a 15-year furlough in the 80s and 90s, Ardbeg was bought by Glenmorangie and reopened in late 1997. In 2007, when the first batch of Ardbeg 10 was still two years away, the owners decided to raise awareness by opening some casks and releasing a limited bottling of eight-year-old whisky. As its name says, the whisky is still young. We could taste the delicious smoky notes that define the 10, but it is still harsh and unrefined.

Grooves (Committee Release): Finished in charred red wine casks, Grooves combines smokiness with sweeter notes of vanilla sugar and dried fruit.

Supernova (Committee Release): With around twice the phenolic content of Ardbeg 10, this is most heavily peated whisky Ardbeg has ever made. It tasted like burning.

Kelpie (Committee Release): My favorite of the whiskies we tried on the bog walk, it was very nicely balanced with a bit more saltiness and a little less smoke than the standard Ardbeg 10.

About a mile or so into the bog, we stopped for lunch at the abandoned 18th-century croft of Solam. According to local legend, the villagers perished after taking in a crew of shipwrecked sailors afflicted with plague. The story has been largely discredited, but the ruins are evocative nonetheless--even on such a beautiful day as this, with the gorgeous emerald glen illuminated behind it.

Scattered throughout the rocks and ruins around Solam are a series of subtly carved faces. No one knows exactly where they came from or how many of them there actually are, and hunting for them seems to be a popular pastime among tourists and guides.

As we made our way back to Ardbeg (going all the way to Uigeadail would be a full day's trek), we got to see some more incredible views of the coast. It was so clear, we could even see the northern coast of Ireland far on the horizon. Dougie stopped us at one point to show us some of the cut peat that gives Islay whisky its distinctive flavor. As we'd been taught on our Connemara trip in Ireland, dried peat was used as an everyday fuel source across the British Isles throughout its history. Today, Islay distilleries smoke their barley with peat smoke before fermentation, giving it that characteristic smoky, maritime flavor.

Back at the distillery, we got a quick peek inside to meet one of the distillers and see the iconic copper pot stills.

Nearly all Scotch whiskies are double distilled. After the smoked barley is fermented, the resulting "wash"--which is essentially beer--is distilled in the "wash still." The stuff that comes out of the wash still is called low wine, which is very harsh and only about 20% alcohol by volume. The low wine is then fed into a "spirit still," which distills the low wine into spirit, which is then in turn put into barrels for aging. Only after a minimum of three years can the spirit legally be called Scotch whisky.

We also got our first introduction to the brass lock boxes called spirit safes, which are used to monitor and direct the flow of low wine and spirit as they are produced.

Every distillery in Scotland has a spirit receiver very much like this one, and the reason is taxation. Historically, alcohol taxes were a vital component of government revenue, and unlicensed whisky production was a high crime. Unlicensed distilleries (which many of today's famous distilleries started as) were hunted down and quashed, and licensed distilleries were required to house and pay a government "exciseman" to keep them honest. As part of that process, every drop of spirit that a distillery produced had to be funneled through a locked, windowed box where the exciseman could monitor just how much they were producing.

Today, distilleries are trusted to handle the bookkeeping themselves, but they still use the same brass spirit safes.

The tour ended on the pier, where we tasted the Kelpie and admired the view of Ardbeg's name painted in huge block letters across the side of its warehouse.

The sun still beating down on us, we walked back down the road to Lavagulin, maker of my dad's favorite Lagavulin 16. We had booked their core range tasting tour, which included a 30-minute distillery tour and a tasting session with three whiskies.

Unlike Ardbeg, we weren't allowed to take any pictures inside the distillery, and to be brutally honest the tour wasn't especially memorable. The tour was led by a local high-schooler who did her best, but her stories and banter were no match for the fare we enjoyed on Dougie's bog walk.

Guiding distillery tours seems to be a common summer job among Islay's youth. Like rural places around the developed world, Islay has a problem with population drain. Its youth head to the mainland to attend university, and many never come back. To fight this, the distilleries are making an effort to recruit local teens and offering them university scholarships. In exchange, the students agree to return after graduation and work at the distillery for a few years, where (the hope is) that they will put down roots and decide to stay long-term. The arrangement seems to be working well for both parties.

The tour ended in Lagavulin's well-appointed tasting room, filled with comfy high-backed chairs and display cases full of priceless old whiskies.

There we tasted three whiskies, with the last one served in an engraved Lagavulin glass that we got to take with us. (A recurring theme in our distillery visits across Scotland.)

Lagavulin 8: A bicentennial anniversary edition released in 2016, this is Lagavulin's take on a young and citrusy whisky. It was a bit harsh at first, but a drop of water opened up the flavors beautifully.

Distiller's Edition: A blend of two different vattings, one with a sherry finish and one without. It was tasty and well-balanced with a variety of smoky and spicy flavors, none of which outdid the others. The sort of whisky that's easy to enjoy but hard to describe--at least for novices like us.

Jazz 2017: Made for the 2017 Islay Jazz Festival, this cask-strength whisky was hot and spicy at first, but a drop of water opened up sweet and smoky flavors, too. My dad and Jessica liked it a lot, but It wasn't as much to my taste.

Despite being a "core range" tasting, only the Distiller's Edition was actually part of Lagavulin's regularly available lineup. But to be fair, Lagavulin only has two core whiskies at the moment: Lagavulin 16 and the Distiller's Edition.

Looking back, Lagavulin felt simultaneously stiffer and less organized than many other distilleries we visited. This may have just been our own biases going in, but it felt a bit as though they have such a prestigious reputation that they just don't need to try as hard to make their tours engaging. Of course, we had just come from the extremely fun and memorable tour at Ardbeg, so that probably tainted our perceptions at least a little.

That isn't to say that we didn't enjoy ourselves or that we wouldn't go back. We definitely did and we definitely would. We'd probably just spring for one of their more interesting tours.

As we walked the two remaining miles back to Port Ellen under the unrelenting summer sun, all of the day's walking finally hit us hard. Ironically, today--our first full day in the Scottish Isles--was when we got our worst sunburns of the trip. But we made it back just fine in the end, with plenty of time to make dinner and rest up for our next day of tasting and exploration.

Next Post: Bowmore and Laphroaig

Last Post: Islay (Introduction and Arrival)

0 notes

Text

Our Food for the Many Rainy Days Ahead added to Google Docs

Our Food for the Many Rainy Days Ahead

Goa’s monsoon season has long necessitated the practice of purumenth, or stocking up. Today, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s a new kind of lifesaver.

We were the crow chasers.

Armed with rolled-up newspapers and sticks, we three siblings waited on the balcão (balcony) guarding the choris (Goan sausages) that were draped over a bamboo rod perched above the ground. Inside, the family sat on the floor mixing pork with local toddy vinegar, chiles, and spices, stuffing it into a casing of pigs’ intestines. A cotton thread tied off links, forming a meaty necklace dripping with fat and staining everything red.

These meat necklaces were our assignment, and they attracted crows by the dozen. The sausages hovered over freshly sourced chiles from different villages, solam (kokum), tamarind, mangoes, and fish, all spread on newspaper or mats woven from coconut palms. The salty aromas, mingled with the afternoon heat, proved irresistible to the birds. Fighting them off on hot summer days was our main source of entertainment during this long and tedious process, and we fought bravely.

These items, after all, were important — this was our purumenth, our food for the many rainy days ahead.

Purumenth (sometimes spelled purument or purmenth) is the local Konkani corruption of the Portuguese word provimento or provisão, meaning provisions. It is, most simply, the practice of stocking up for times when food is scarce.

Goa is a small state on India’s west coast. Ruled by the Portuguese from around 1510 until 1961, Goa today is known for being a popular travel destination thanks to its distinct cuisine, cultural diversity, cheap alcohol (tax rates on booze vary throughout India, and Goa has among the lowest), and beachy, laid-back life compared to cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

It’s also known for monsoons.

India’s monsoon season follows the hot, dry summer months of April and May and it lasts from June until September. The rain is fickle, alternating between light drizzles and heavy downpours that cause destructive flooding, limiting transportation and the mobility of goods and people — and, historically, making fresh ingredients like produce, meat, and fish scarce.

“Until a few decades back, provisions for the rains had to be gathered well in advance as the rains were unpredictable, weather forecasting was unknown, and refrigeration facilities non-existent,” writes historian Fátima da Silva Gracias in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through.”

For decades, my family — like many others in villages across the state — would stock up for the harsh and volatile monsoon. Preparations began early, from mid-February onward. April and May, then, were months of abundance, of cheap goods and busyness. Food was procured, cleaned, sun-dried, pickled, and stored.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through,” says archaeologist and culinary anthropologist Kurush F. Dalal. “Everybody stocked things on a yearly basis — masala, dals and ghee, pickles, dry fish, salt, and pappad. It wasn’t frugality, but systematic planning to ensure the larder was always full.”

Everything had to be ready by mid-May in case of early showers. Those who were unable to prep in time by themselves could stock up at Purumentachem Fests held at the end of May and early June. These fairs were linked to the annual church feasts in the cities of Margao and Mapusa, which, since they occurred around time the monsoons began to sweep in, sold a variety of purumenth staples for last-minute shoppers.

For the most part, purumenth is the stuff of culinary history. Over the last few decades, the arrival of refrigerators to store produce, the availability of fresh goods throughout the monsoons, and increased mobility between villages and cities have made stocking up less crucial. Purumenth fairs still occur annually, and locals still stock up on dried fish, rice, vinegar and pickles, but lately they’ve been less driven by necessity than nostalgia — “preparing” less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

But then COVID hit. On March 24, Goa, like the rest of India, went into a government-mandated lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. The announcement was a surprise and ill-planned, leaving people with no time to prepare. In the initial days, people weren’t allowed to leave their homes; shops and markets were shuttered, and there was no public transportation. In many places, people started rationing meals as supplies started to run out. For the first time in a long time, food was hard to come by.

In the villages, elders nodded their heads wisely. It wasn’t the monsoon season yet, but they knew how to deal with this enforced isolation. They had been storing provisions for years and had a diminished but stocked larder. It was our younger generation that struggled, spoiled by abundance of choice and instant gratification, and living in homes where space is too premium to be utilized for storing goods.

“Our ancestors were smart enough to live by the seasons. But we’ve become greedy, and our demands have exceeded our supply,” says Avinash Martins, chef and owner of Cavatina Cucina. “Had we to follow our ancestral cycle, we wouldn’t have taken our food for granted.”

In the olden days, Goan kitchens had a cow dung-smattered floor and an earthen stove. On a bamboo rod placed high across the kitchen hung local white onions and sausages — the smoke from the fireplace kept the insects away — and most houses had a designated storage area, a secluded corner, the space under the bed or a dark room.

This space, while not exactly photogenic, offered a snapshot of summer bounty like cheap fresh fish, mangoes, jackfruit, chiles, and cashews. Here, too, lay all the dried, salted, and cured produce. There was kokum, tamarind balls, whole spices, masalas, and bhornis (porcelain jars) with pickles like chepne tor (flattened raw mangoes in brine). Some families had mitantulem mas — salted pork drained of its water via heavy weights and dried into a jerky of sorts. There was coconut oil and vinegar made from the toddy extracted from the coconut palms. Summer fruits like jackfruit and mangoes — including the seeds — were peeled, sliced, and dried for use in curries.

My family still lives in a small village in the north of Goa, in an old Indo-Portuguese house. Back in the 1930s and ’40s, the building had a separate room dedicated to rice. The bhathachim kudd (paddy room) was in the center of the house with no direct access to sunlight, keeping it cool and dark, and had a roughly hewn bamboo structure filled with paddy — rice with husk — from our fields.

“Preparing” has become less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

“We dried the paddy in the sun to prevent insects from eating it, and parboiled it in a bhann [a big copper pot],” says Maryanne Lobo, an Ayurvedic doctor in Goa whose family also had a bhathachim kudd. “Once boiled, we took it to the mill to remove the bran, and stored the rice in a dhond [a barrel-like container].”

Lobo learned about purumenth from her maternal aunt. “She would store jackfruit seeds in a hole dug into the floor. She used the mud from an ant hill to create a well and covered the top with cow dung mixture. This kept the seeds dry and free from insects.” Dried jackfruit seeds were cooked like a vegetable, or added to curries.

Like her aunt, Lobo still stocks up religiously every summer. She doesn’t have a storeroom anymore, so the paddy is dried in her balcony, and she stores her jackfruit seeds in sand. The traditional jars have given way to plastic bottles, and provisions are stocked beneath beds — but still, she says “purumenth was a lifesaver” during the lockdown.

There’s something overwhelming and intoxicating about the smell of dried fish — fierce, pungent, and fermenting. Traditionally, in the monsoon months fishermen could not venture out into the choppy sea, so good fish was scarce. Locally caught fish from rivers and ponds was limited and expensive. People, then, preferred eating kharem (salted fish).

Goa’s typical dried fish stock includes the common mackerel, salted and dried and pickled to become a para with vinegar and masalas; dried shrimp; and prawns — pickled into a tangy molho or balchao, or dried. In the monsoon, this fish forms the accompaniments to a simple lunch of rice and plain curry, or to the mid-morning meal of pez (rice gruel). Dried shrimp becomes kismur — a dry salad made with coconut and tamarind, for which the prawns are roasted over a flame with coconut oil and the para is fried and roasted.

Fish was high on Marius Fernandes’s summer prep this year. Known as Goa’s “Festival Man” — responsible for conducting more than 40 cultural festivals in the region — Fernandes has dedicated his life to promoting the traditional Goan way of life. On lockdown in the small island village of Divar, he spent the summer doing prep under the guidance of his 88-year-old mother, Anna. The family dried and pickled prawns and mackerel, seeds, ripe and raw mangoes, jackfruit, pineapples, and tomatoes. “The situation with regards to sourcing fresh food is only going to get worse in this current situation,” says Fernandes, who has spent much of the last few months in the family garden. “We have to start thinking about growing our own food.”

Like Fernandes, the few who never stopped practicing purumenth are eloquent about its benefits. And those who are rediscovering it now, in response to COVID-19 shortages, are finding that it fits well into the modern ethos surrounding eating. “This is the new gourmet: food that is harvested locally, is seasonal, organic, grown in small batches, with a zero-carbon footprint,” says Cavatina Cucina’s Martins, who became more conscious about his food back in 2018 when the toxic chemical formalin was found in fish and led to a scare in Goa. Today he makes and stores pickles, fish, chiles, and salt.

“Because of the lockdown, we again know about all the wonderful produce available here,” says Fernandes. “Earlier, these would go to markets and supermarkets. Now, we are getting first pick of this locally grown, organic produce.”

Today, my larder in Mumbai has a few traces of purumenth: some salted shrimp and a pack of sausages. There have always been sausages in my kitchen, my way of connecting back to my home in Goa. There’s no need to fight off any crows, though — just my dog, who is equally fascinated by fragrant links of choris.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist from India who enjoys writing about food and its ties to communities, her Goan heritage, and other things that make her happy. Roanna Fernandes is an illustrator from Mumbai.

via Eater - All https://www.eater.com/21333015/goa-india-purumenth-monsoons-pantry-food-for-rainy-days-coronavirus-covid-19

Created August 4, 2020 at 12:26AM

/huong sen

View Google Doc Nhà hàng Hương Sen chuyên buffet hải sản cao cấp✅ Tổ chức tiệc cưới✅ Hội nghị, hội thảo✅ Tiệc lưu động✅ Sự kiện mang tầm cỡ quốc gia 52 Phố Miếu Đầm, Mễ Trì, Nam Từ Liêm, Hà Nội http://huongsen.vn/ 0904988999 http://huongsen.vn/to-chuc-tiec-hoi-nghi/ https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1xa6sRugRZk4MDSyctcqusGYBv1lXYkrF

0 notes

Photo

skoolz out! this morning my advisees asked if i ever feel like an adult and i said nope to which they basically said good because they feel like they're never gonna feel like adults and i said good. then i went home and the first thing i did was trim my hedges and clean all the trash that was under them. #solame #adulting #adultingsohard #adultingsucks #schoolsout #summer #yardworksucks via Instagram http://ift.tt/2sUEsYv

0 notes

Text

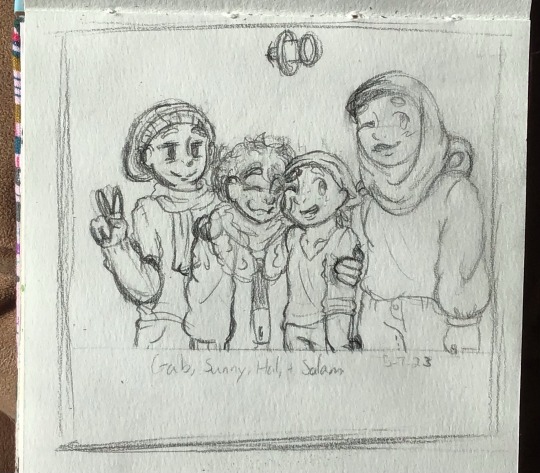

a wip shot of a group photo of Wild Ventures’ newest members

Gab and Solam joined a few months before Sunny and Hal, but they thought it was a fun idea!

#my art#morning; 14.3 billion years later#morning (hal)#morning (gab)#morning (solam)#morning (sunny)#my oc#i had so much trouble with sunny’s face. like you wouldn’t believe#still not sure i’m entirely happy with it so it might change again#by the time i’m done#and gab’s arm still looks off hhhhh#i’m trying not to nitpick this too much + it’s gonna be changed at least a little anyway by the time it’s done#but it bothers me *now* ::/

0 notes

Quote

Goa’s monsoon season has long necessitated the practice of purumenth, or stocking up. Today, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s a new kind of lifesaver.

We were the crow chasers.

Armed with rolled-up newspapers and sticks, we three siblings waited on the balcão (balcony) guarding the choris (Goan sausages) that were draped over a bamboo rod perched above the ground. Inside, the family sat on the floor mixing pork with local toddy vinegar, chiles, and spices, stuffing it into a casing of pigs’ intestines. A cotton thread tied off links, forming a meaty necklace dripping with fat and staining everything red.

These meat necklaces were our assignment, and they attracted crows by the dozen. The sausages hovered over freshly sourced chiles from different villages, solam (kokum), tamarind, mangoes, and fish, all spread on newspaper or mats woven from coconut palms. The salty aromas, mingled with the afternoon heat, proved irresistible to the birds. Fighting them off on hot summer days was our main source of entertainment during this long and tedious process, and we fought bravely.

These items, after all, were important — this was our purumenth, our food for the many rainy days ahead.

Purumenth (sometimes spelled purument or purmenth) is the local Konkani corruption of the Portuguese word provimento or provisão, meaning provisions. It is, most simply, the practice of stocking up for times when food is scarce.

Goa is a small state on India’s west coast. Ruled by the Portuguese from around 1510 until 1961, Goa today is known for being a popular travel destination thanks to its distinct cuisine, cultural diversity, cheap alcohol (tax rates on booze vary throughout India, and Goa has among the lowest), and beachy, laid-back life compared to cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

It’s also known for monsoons.

India’s monsoon season follows the hot, dry summer months of April and May and it lasts from June until September. The rain is fickle, alternating between light drizzles and heavy downpours that cause destructive flooding, limiting transportation and the mobility of goods and people — and, historically, making fresh ingredients like produce, meat, and fish scarce.

“Until a few decades back, provisions for the rains had to be gathered well in advance as the rains were unpredictable, weather forecasting was unknown, and refrigeration facilities non-existent,” writes historian Fátima da Silva Gracias in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through.”

For decades, my family — like many others in villages across the state — would stock up for the harsh and volatile monsoon. Preparations began early, from mid-February onward. April and May, then, were months of abundance, of cheap goods and busyness. Food was procured, cleaned, sun-dried, pickled, and stored.

“The whole western coast would batten down the hatches before the monsoons came howling through,” says archaeologist and culinary anthropologist Kurush F. Dalal. “Everybody stocked things on a yearly basis — masala, dals and ghee, pickles, dry fish, salt, and pappad. It wasn’t frugality, but systematic planning to ensure the larder was always full.”

Everything had to be ready by mid-May in case of early showers. Those who were unable to prep in time by themselves could stock up at Purumentachem Fests held at the end of May and early June. These fairs were linked to the annual church feasts in the cities of Margao and Mapusa, which, since they occurred around time the monsoons began to sweep in, sold a variety of purumenth staples for last-minute shoppers.

For the most part, purumenth is the stuff of culinary history. Over the last few decades, the arrival of refrigerators to store produce, the availability of fresh goods throughout the monsoons, and increased mobility between villages and cities have made stocking up less crucial. Purumenth fairs still occur annually, and locals still stock up on dried fish, rice, vinegar and pickles, but lately they’ve been less driven by necessity than nostalgia — “preparing” less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

But then COVID hit. On March 24, Goa, like the rest of India, went into a government-mandated lockdown to curb the spread of COVID-19. The announcement was a surprise and ill-planned, leaving people with no time to prepare. In the initial days, people weren’t allowed to leave their homes; shops and markets were shuttered, and there was no public transportation. In many places, people started rationing meals as supplies started to run out. For the first time in a long time, food was hard to come by.

In the villages, elders nodded their heads wisely. It wasn’t the monsoon season yet, but they knew how to deal with this enforced isolation. They had been storing provisions for years and had a diminished but stocked larder. It was our younger generation that struggled, spoiled by abundance of choice and instant gratification, and living in homes where space is too premium to be utilized for storing goods.

“Our ancestors were smart enough to live by the seasons. But we’ve become greedy, and our demands have exceeded our supply,” says Avinash Martins, chef and owner of Cavatina Cucina. “Had we to follow our ancestral cycle, we wouldn’t have taken our food for granted.”

In the olden days, Goan kitchens had a cow dung-smattered floor and an earthen stove. On a bamboo rod placed high across the kitchen hung local white onions and sausages — the smoke from the fireplace kept the insects away — and most houses had a designated storage area, a secluded corner, the space under the bed or a dark room.

This space, while not exactly photogenic, offered a snapshot of summer bounty like cheap fresh fish, mangoes, jackfruit, chiles, and cashews. Here, too, lay all the dried, salted, and cured produce. There was kokum, tamarind balls, whole spices, masalas, and bhornis (porcelain jars) with pickles like chepne tor (flattened raw mangoes in brine). Some families had mitantulem mas — salted pork drained of its water via heavy weights and dried into a jerky of sorts. There was coconut oil and vinegar made from the toddy extracted from the coconut palms. Summer fruits like jackfruit and mangoes — including the seeds — were peeled, sliced, and dried for use in curries.

My family still lives in a small village in the north of Goa, in an old Indo-Portuguese house. Back in the 1930s and ’40s, the building had a separate room dedicated to rice. The bhathachim kudd (paddy room) was in the center of the house with no direct access to sunlight, keeping it cool and dark, and had a roughly hewn bamboo structure filled with paddy — rice with husk — from our fields.

“Preparing” has become less a practice than a memory, one looked upon fondly by the older generations.

“We dried the paddy in the sun to prevent insects from eating it, and parboiled it in a bhann [a big copper pot],” says Maryanne Lobo, an Ayurvedic doctor in Goa whose family also had a bhathachim kudd. “Once boiled, we took it to the mill to remove the bran, and stored the rice in a dhond [a barrel-like container].”

Lobo learned about purumenth from her maternal aunt. “She would store jackfruit seeds in a hole dug into the floor. She used the mud from an ant hill to create a well and covered the top with cow dung mixture. This kept the seeds dry and free from insects.” Dried jackfruit seeds were cooked like a vegetable, or added to curries.

Like her aunt, Lobo still stocks up religiously every summer. She doesn’t have a storeroom anymore, so the paddy is dried in her balcony, and she stores her jackfruit seeds in sand. The traditional jars have given way to plastic bottles, and provisions are stocked beneath beds — but still, she says “purumenth was a lifesaver” during the lockdown.

There’s something overwhelming and intoxicating about the smell of dried fish — fierce, pungent, and fermenting. Traditionally, in the monsoon months fishermen could not venture out into the choppy sea, so good fish was scarce. Locally caught fish from rivers and ponds was limited and expensive. People, then, preferred eating kharem (salted fish).

Goa’s typical dried fish stock includes the common mackerel, salted and dried and pickled to become a para with vinegar and masalas; dried shrimp; and prawns — pickled into a tangy molho or balchao, or dried. In the monsoon, this fish forms the accompaniments to a simple lunch of rice and plain curry, or to the mid-morning meal of pez (rice gruel). Dried shrimp becomes kismur — a dry salad made with coconut and tamarind, for which the prawns are roasted over a flame with coconut oil and the para is fried and roasted.

Fish was high on Marius Fernandes’s summer prep this year. Known as Goa’s “Festival Man” — responsible for conducting more than 40 cultural festivals in the region — Fernandes has dedicated his life to promoting the traditional Goan way of life. On lockdown in the small island village of Divar, he spent the summer doing prep under the guidance of his 88-year-old mother, Anna. The family dried and pickled prawns and mackerel, seeds, ripe and raw mangoes, jackfruit, pineapples, and tomatoes. “The situation with regards to sourcing fresh food is only going to get worse in this current situation,” says Fernandes, who has spent much of the last few months in the family garden. “We have to start thinking about growing our own food.”

Like Fernandes, the few who never stopped practicing purumenth are eloquent about its benefits. And those who are rediscovering it now, in response to COVID-19 shortages, are finding that it fits well into the modern ethos surrounding eating. “This is the new gourmet: food that is harvested locally, is seasonal, organic, grown in small batches, with a zero-carbon footprint,” says Cavatina Cucina’s Martins, who became more conscious about his food back in 2018 when the toxic chemical formalin was found in fish and led to a scare in Goa. Today he makes and stores pickles, fish, chiles, and salt.

“Because of the lockdown, we again know about all the wonderful produce available here,” says Fernandes. “Earlier, these would go to markets and supermarkets. Now, we are getting first pick of this locally grown, organic produce.”

Today, my larder in Mumbai has a few traces of purumenth: some salted shrimp and a pack of sausages. There have always been sausages in my kitchen, my way of connecting back to my home in Goa. There’s no need to fight off any crows, though — just my dog, who is equally fascinated by fragrant links of choris.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist from India who enjoys writing about food and its ties to communities, her Goan heritage, and other things that make her happy. Roanna Fernandes is an illustrator from Mumbai.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2BRZe54

http://easyfoodnetwork.blogspot.com/2020/08/our-food-for-many-rainy-days-ahead.html

0 notes