#monthly patchy special edition

Text

patchy says trans rights

#monthly patchy special edition#my art#touhou#東方#patchouli#patchouli knowledge#東方project#touhou project

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Blake Edwards’ 1982 film Victor/Victoria, there is a bittersweet moment when Victoria Grant (Julie Andrews), the down-on-her-luck English protagonist stranded in Depression-era Paris, drops her hitherto plucky facade and dissolves into weepy distress. Having been caught in a wintry downpour with newfound gay friend, Toddy (Robert Preston), Victoria retreats to Toddy’s apartment to dry off and enjoy a cognac-fuelled heart-to-heart. When she subsequently tries to slip back into her now dried clothes, Victoria discovers to her horror that they have shrunk to tattered rags.

“My best dress,” she wails in shock at the waifish reflection in the dressing mirror.

“I can’t go out like this…What am I going to do?!”

“Sell matches!” retorts Toddy in a vain attempt to jolly the situation. Victoria manages a wan chuckle before collapsing in tears into Toddy’s comforting embrace.

The reference in this scene to Hans Christian Andersen’s “Little Matchgirl” is clear enough but Toddy’s gentle quip harbours another, potentially more pointed, intertextual allusion.* Star Julie Andrews actually played the Little Matchgirl in a 1959 tele-musical adaptation of the classic Andersen fairy tale made for BBC TV.

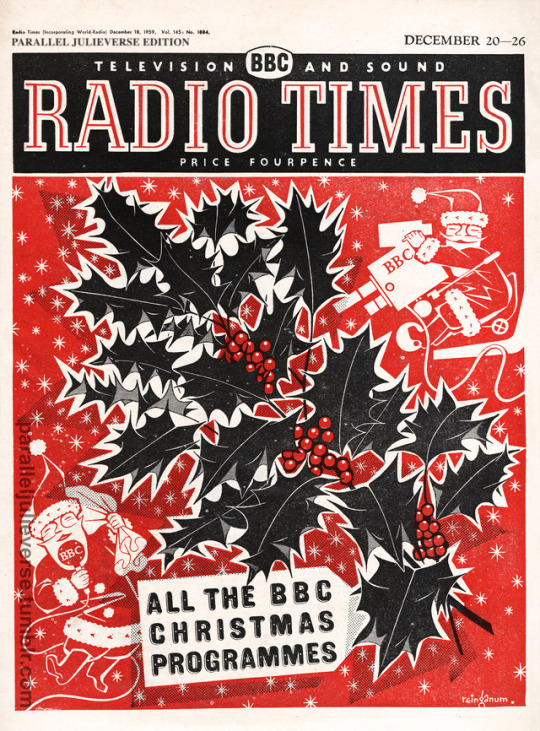

Titled The Gentle Flame, the programme was something of a landmark event in British broadcast history. One of the most ambitious TV musical projects undertaken to that date by the BBC, The Gentle Flame was developed as a tailored showcase for Julie Andrews, with a specially commissioned script by writer-director Francis Essex (Essex, 40), and a suite of new songs from Ronald Cass and Peter Myers, the composer-lyricist team who would later go on to write a string of hit film musicals for Cliff Richard (Donnelly, 144-46). Airing in peak time on Christmas Eve, The Gentle Flame was promoted as a major holiday entertainment and it attracted a substantial national audience (Cowan, 5).

To put The Gentle Flame in historical context, the 1950s was a period of profound transformation for British broadcasting. In 1954, the nation’s booming television market was opened to commercial competition with the creation of the ITA (Independent Television Authority) and the BBC suddenly lost its privileged monopoly as the sole TV network (Briggs, vol. V, 3ff; Holmes, 2ff). Confronted with a new landscape of competition and changing popular tastes, the iconic UK broadcaster moved to improve its marketability with an expanded range of audience-friendly fare.

Earlier in the decade, the BBC had appointed Ronald Waldman as Head of its TV Light Entertainment Division and he was influential in overhauling the network’s programme offerings (Briggs, vol. V, 24). A seasoned industry veteran with many years experience as a successful radio producer, Waldman believed that the key to attracting a mass audience was the strategic use of “star power”. In a 1956 memo discussing the results of an internal audience research bulletin, Waldman noted with alarm how “two out of three viewers declares [sic] the ITA was better than the BBC in the matter of Variety…and stars” and that the broadcaster “must try and get some personalities” (cited in Bennett, 56).

One of the “personalities” high on Waldman’s wish list was Julie Andrews. Years previously, Waldman had played an instrumental role in Julie’s early career when he introduced her as a ‘child prodigy’ to the airwaves of Britain on his popular radio show, “Tonight at 8″ in 1947. It was a longstanding professional association shared by other members of senior management at BBC-TV. When Waldman was promoted to Executive Business Manager of Programming in 1958, his former role of Light Entertainment Head was taken over by Eric Maschwitz who, as it happens, had also worked with Julie in her child star years on the production team of Starlight Roof (Briggs, vol. V, 196). It’s possibly not surprising, then, that “the Beeb” should have been keen to secure Julie for its expanding roster of television ‘names’ in the late-50s.

Not that Julie was exactly a stranger to the small screens of Britain. She had made her television debut as far back as 1948 appearing on Rooftop Rendezvous alongside parents, Ted and Barbara Andrews (”Rooftop”, 27). She then popped up with some regularity across the early 1950s as a guest on assorted TV musical variety revues and quiz shows. She even made a high profile appearance on the “commercial competition,” performing in 1955 on ATV’s hugely popular Sunday Night at the London Palladium, produced by another old-time associate, Val Parnell (Gray, 12). By the time Julie returned to the UK in 1958 as the triumphant star of My Fair Lady, her celebrity was at an all-time high and conditions were ripe for promotion to TV leading lady in her own right.

In what was claimed to be “one of the biggest fees ever paid to a British star”, Julie was signed by the BBC in May 1959 to an exclusive deal for “four hour-long TV spectaculars” (”Julie Signs,” 3). Originally scheduled as monthly broadcasts to start in June, the series was subsequently postponed until after Julie had finished her London run in My Fair Lady in the autumn (”Julie’s TV Show Postponed”, 3). Meanwhile, the BBC built up public anticipation by featuring Julie in a special pre-filmed appearance on Harry Secombe’s popular variety show, Secombe at Large (30 May 1959, BBC). It also secured rights to Julie’s appearance on The Jack Benny Show from CBS in the US which it broadcast in September (Noble, 6).

Finally, on November 12, the first of Julie’s four specials for the BBC bowed amidst much fanfare (“Highlights,” 9). Simply called The Julie Andrews Show, the 45-minute specials (slightly shorter than the originally announced one hour format) were broadcast fortnightly on a Thursday evening at 7:30pm. The first three entries followed a standard TV variety format with Julie hosting, singing, performing and chatting with a roster of changing guest stars. The fourth and final entry took a different approach, devoting the timeslot to the premiere production of a new Christmastime musical, The Gentle Flame (”Gentle,” 7).

A loose adaptation of Andersen’s “Little Matchgirl,” The Gentle Flame starred Julie as Trissa, the nineteenth-century beggar girl who uses her last box of matches to keep warm on a bitterly cold snowbound night. One by one she lights the matches and:

“as she does so she is transported into a world of music, beautiful gowns and dancing. She meets a young man and falls in love but when she discovers that the room in which she met him had been boarded up a long time ago, she finds herself poor and back in the street again” (Taylor, 8).

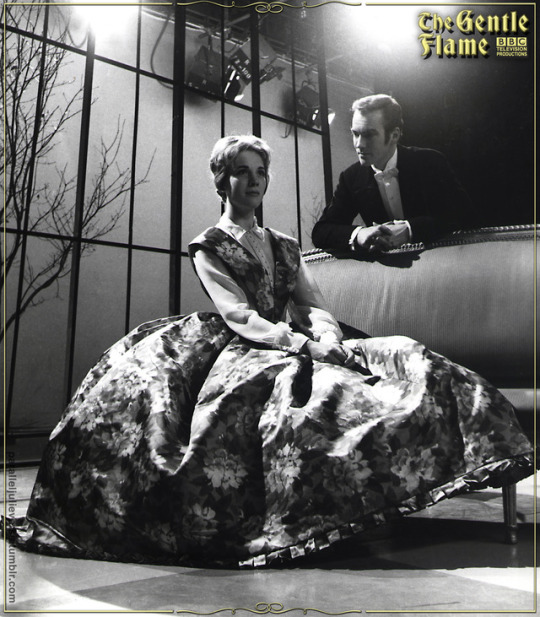

Appearing alongside Julie in the programme was a supporting cast of seasoned character actors including John Fraser as Charles the fantasy suitor, Jay Denyer as the Shopkeeper, and Pauline Loring as the haughty Rich Woman. Special musical support was provided by members of the Brompton Oratory Boys Choir (”Gentle,” 19).

In many ways, The Gentle Flame was not unlike a smaller-scale British Cinderella, the celebrated 1956 TV musical created by Rodgers and Hammerstein for Julie. Yet, despite its considerable cultural and historical significance, The Gentle Flame has largely fallen into obscurity. As far as can be ascertained, it hasn’t ever been seen since its initial broadcast almost sixty years ago and it is overlooked in all but the most exhaustive historical commentaries. Even Julie herself gives the programme short shrift. In her memoirs, she dispenses with the BBC series in a few short paragraphs, concluding with the matter-of-fact summation: “We ended up with four fairly good shows, the final episode airing on Christmas Eve” (268).

So what happened to The Gentle Flame and why isn’t it a bigger deal today? For a start, there is a question mark over whether or not a copy of the programme exists or, for that matter, ever did. Sadly, both the BBC and the BFI (British Film Institute) report that they don’t hold The Gentle Flame in their libraries and that there are no known records of it in any other archival repository (BBC Archives, personal communication, 11 November 2017).

Up until the 1960s, most British television content was produced via live transmission and wasn’t typically recorded (Holmes, 9-10). Some select programmes were filmed in advance and others of special note were captured for subsequent rebroadcast and/or preservation using telecine cameras (in much the same way that Cinderella was recorded as a kinescope by CBS), but the lion’s share of TV content was live and unrecorded. Industry practice started to change in the late 1950s with the advent of videotape technology but, because it was prohibitively expensive, its incorporation was patchy. As late as 1963, less than a third of BBC programming was routinely recorded (Turnock, 95-96).

In the case of The Gentle Flame, it is difficult to determine the exact technical status of its production. Not only is there no known copy of the original broadcast but, even more disconcertingly, BBC Written Archives have “not retained any production files for The Gentle Flame or other Julie Andrews Specials” (BBC Archives, personal communication, 11 November 2017). All that exists in “official holdings” is a microfilm copy of the script, an audience research report, and a handful of production stills. In the absence of concrete documentary evidence and/or a labour-intensive detective hunt through papers and collections that may still be in existence from people involved in the production, all we can ultimately do is speculate about how The Gentle Flame was produced and if a recorded copy was ever made.

Technical credits for the programme list an entry for “film sequences” by A. Arthur Englander and editing by Pamela Bosworth (“Gentle,” 19). This would suggest that at least some of the programme’s material was pre-filmed. The most likely scenario is that it was produced as a mix of live broadcast and pre-filmed sequences. This hybrid style was fairly common practice for BBC programmes of the era where pre-filmed sequences would be inserted into an otherwise live broadcast, typically to add exteriors or special effects shots that were impossible to do in a studio or to offer a “breathing space” for costume and scenery changes (Turnock, 87).

There is certainly evidence that this practice of mixing live and pre-filmed sequences was used in earlier episodes of The Julie Andrews Show. Newspaper reviews make mention of the fact that, among other things, a comic sketch between Julie and Kenneth Williams in Episode 1 and an animated sequence and appearance by Stanley Holloway in Episode 3 were all pre-recorded inserts (Erni, 23 Dec., 38; Sear 26; Taylor 16). In the case of The Gentle Flame, it is most likely that the fantasy sequences with Julie and John Fraser at the ball would have been pre-filmed. Publicity photos reveal dramatic costume and hairstyle changes in these scenes that would have been difficult to negotiate in an exclusively live format. So, at a minimum, some of the material elements from The Gentle Flame must have existed in a recorded format.

Furthermore, given the unprecedented expense and prestige of these Julie Andrews specials, it beggars belief that the BBC wouldn’t have recorded them in some form or other –– if not for posterity, at least with an eye to possible rebroadcast and/or extended distribution. Historian Rob Turnock (2006) notes that, as early as 1952, the BBC was recording select live performances and staged programmes and even “established a transcription unit to distribute telerecordings and purpose made BBC films abroad” (90). Moreover, much of the reason the BBC commissioned their own staff writers to develop new programmes––as they did with The Gentle Flame––was to “generate material that it owned and could record by itself” without having to negotiate permission and clearance from external rights holders (ibid.).**

However, even if the BBC did record The Gentle Flame, it is no guarantee that the recording would still be in existence today. Because TV was widely viewed in the era as a transient medium of live communication –– in much the same way as radio or theatre –– there was little sense that TV programmes had lasting value or should be conserved beyond the period of their immediate use. It wasn’t till 1978 that the BBC initiated an archival policy but, by this stage, it was estimated that over 90% of all previous programming had been destroyed, whether through outright disposal or through wiping over for re-use (Fiddy, 3). When the BBC made the move to colour transmission in 1967, for example, it undertook a wholesale junking of old monochromatic programmes in the misguided belief that they no longer had appreciable value or purpose (Fiddy, 8). Hours of content from even hugely popular BBC series such as Doctor Who, Steptoe and Son, and Dad’s Army were lost in this way.

So if The Gentle Flame were indeed recorded, any copies would really need to have defied the odds to have survived to the present day. But, who knows? Events like the BFI’s annual “Missing, Believed Wiped” public appeal have had great success in turning up many BBC programmes previously presumed lost forever. So maybe a copy of The Gentle Flame is lurking in some dusty, out-of-the-way storage facility somewhere just waiting to be rediscovered. If you’re reading this, Dame Julie, Check the attic!

Finally, the question remains: was The Gentle Flame any good? Well, critical reception of the programme was, it must be said, mixed. Maurice Wiggin of the Sunday Times called it “charming Christmastime fare” that displayed “cunning visual talent at full stretch,” though added as a slightly acerbic aside that writer-director Francis Essex “should stick to directing and leave writing to writers” (20). Guy Taylor, resident critic for The Stage, was positively rhapsodic in his review:

“My Christmas viewing started with Julie Andrews, and what better viewing can you find than that? She appeared with John Fraser in a delightful forty-five minute programme called The Gentle Flame, written and produced by Francis Essex…Everything about this show was right, the photography was delicate, the sets were imaginative and beautifully lit and the special music and lyrics by Peter Myers and Ronald Cass were charming…Essex’s script was excellent blending fairy-tale with the naturalistic and how nice it was to hear English spoken so clearly by Miss Andrews. Essex must have had this in mind when he wrote it.” (31 Dec, 8)

Others were not quite so enchanted. Irving Wardle of The Listener wrote that The Gentle Flame was:

“a really bad example of old-style musical comedy, eliciting push-button responses to such things as a waif in the snow, a ballroom and a Byronic bachelor with pots of money. The legendary association between romance and wealth is unobjectionable, but one does object to the dreadful dialogue (’This is my first ball’) Mr. Essex inflicted on Julie Andrews, and to the fact that he destroyed the sad poetry of the original by making the real world as fanciful as the one the girl imagined” (Wardle, 31 Dec, 11).

So, who knows? The Gentle Flame could be a lost mini-musical treasure or a hamfisted failure. Either way, to see and hear the young Julie Andrews perform a role written just for her during her prime Broadway years would have to be as close as imaginable to the perfect Christmas treat.

Notes:

* Whether or not the reference to the Little Matchgirl in Victor/Victoria is an intentional nod to The Gentle Flame is hard to know. Blake Edwards was certainly a master of satirical allusionism and, like most of the films he made with his wife and longtime collaborator, Victor/Victoria features more than the odd snook at the “Julie Andrews image” including, in this case, quips about nuns, exploding umbrellas, and even recycled jokes from Thoroughly Modern Millie. However, The Gentle Flame isn’t exactly a high profile entry in the Julie Andrews canon, so any intertextual reference would be pretty left-of-field. Interestingly, the joke about the Little Matchgirl in Victor/Victoria was inserted during production. The original shooting script has a different line in this scene:

Victoria: What am I going to do?

Toddy: Well, you could open a boutique for midgets! (Edwards, 34)

** Clutching at straws, Julie does state in her memoirs apropos her BBC TV series that “we would tape one show a week” (279). Of course, the verb “tape” here could be being used symbolically rather than literally, but hope springs eternal.

Sources:

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. New York: Hyperion, 2008.

Bennett, James. Television Personalities: Stardom and the Small Screen. London: Routledge, 2011.

Black, Peter. “Peter Black’s Teleview.” Daily Mail. 13 November 1959: 18.

Briggs, Asa. The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom. Vols I-V. London : Oxford University Press, 1995.

Cottrell, John. Julie Andrews: The Story of a Star. London: Arthur Barker, 1968.

Cowan, Margaret. “TV a Comedown? No, Says Julie.” Picturegoer. 12 December 1959: 5.

Donnelly, K.J. British Film Music and Film Musicals. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

Edwards, Blake. Victor/Victoria. Unpublished screenplay (Final revised version: 23 Feb 1981), Culver City, CA: Blake Edwards Company, 1981.

Erni. “Foreign Television Reviews: ‘The Julie Andrews Show’.” Weekly Variety. 18 November 1959: 34

_______. “Foreign TV Followup: ‘The Julie Andrews Show’.” Weekly Variety. 23 December 1959: 38

Essex, Francis. “Some Passing Memories.” Television: The Journal for the Royal Television Society. Vol. 16. No. 1, 1976: 36-41.

Fiddy, Dick. Missing Believed Wiped: Searching for the Lost Treasures of British Television. London: British Film Institute, 2001.

Forster, Peter. “Television: Instead of Lunch.” The Spectator. 11 December 1959: 878.

“The Gentle Flame.” Radio Times. 20-26 December 1959: 7, 19.

Gray, Andrew. “Julie Andrews is Booked for Sunday Palladium.” The Stage. 6 October 1955: 12.

“Highlight s of the Week: Julie Andrews.” Radio Times. 8-14 November 1959: 9.

Holmes, Su. Entertaining Television: The BBC and Popular Television Culture in the 1950s. Manchester University Press, 2008.

“Julie Signs Up for TV.” Daily Mail. 12 May 1959: 3.

“Julie’s TV Show Postponed.” Daily Mail. 13 June: 3.

Noble, Peter, ed. British Film and Television Yearbook, 1960. London: BA Publications, 1960.

“Rooftop Rendezvous.” Programme Listing. Radio Times. 21-27 November, 1948: 21.

Sear, Richard. “Last Night’s View: The Unspoiled Fair Lady.” Daily Mirror. 13 November 1959: 26.

Taylor, Guy. “In Vision: Julie Andrews Makes Her BBC-TV Debut.” The Stage and Television Today. 19 November 1959: 16.

_______“In Vision: All Those Faithful Viewers.” The Stage and Television Today. 31 December 1959: 8.

Turnock, Rob. Television and Consumer Culture: Britain and the Transformation of Modernity. London: I.B.Tauris, 2006.

Wardle, Irving. Critic on the Hearth: Bitter Rice.” The Listener. 19 November 1959: 8.

__________. “Critic on the Hearth: A Blow Out.” The Listener. 31 December 1959: 11.

Wiggin, Maurice. “Television: Low Tide, High Noon”. The Sunday Times. 27 December 1959: 20.

Wright, Adrian. A Tanner’s Worth of Tune: Rediscovering the Post-War British Musical. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2010.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2017

#julie andrews#television#musical#christmas#bbc#1959#Hans Christian Andersen#the little match girl#the gentle flame#francis essex#ronald cass#peter myers#british musical

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on All about business online

New Post has been published on http://yaroreviews.info/2019/03/riding-with-uncle-diego-ubers-wild-drive-for-growth-in-chile

Riding with 'Uncle Diego': Uber's wild drive for growth in Chile

SANTIAGO (Reuters) – The Uber driver pulled up to the international airport external Chile’s capital. As his passenger jumped into his gleaming Suzuki, he glanced around furtively for signs of trouble.

“Working in the airport isn’t easy,” he told a Reuters reporter, a rosary on the rearview mirror swaying as he raced towards the motorway. “Uber in Chile isn’t easy.”

That is because Uber drivers can be fined or have their vehicles impounded whether caught by authorities ferrying passengers. Chile has yet to work out a regulatory framework for ridesharing.

“This (Uber) application is not legal,” Chile´s Transport Minister Gloria Hutt said final year. “It does not at present comply with Chilean legislation to carry paying passengers.”

Uber’s unregulated status in fast-growing markets such as Chile poses a potential risk for the firm as it prepares for a much-anticipated IPO.

It has in addition launched a cat-and-mouse game of sometimes comical proportions in this South American nation. Drivers warn each other of pick-up & drop-off points where police officers & transport department inspectors are lurking.

They in addition enlist passengers as accomplices. Riders are routinely instructed to sit in the front seat & memorize a cover story – just in case.

“If anyone asks, I’m your friend’s Uncle Diego,” one so-named Uber driver told Reuters on another recent run.

Another, 41-year-old Guillermo, told Reuters his standard alibi for male passengers is that they are his football mates. He & other drivers declined to donate their surnames for fear of being identified by authorities.

Uber’s app & website make no mention of its unsettled legal status in Chile, where it now boasts 2.2 million monthly users & 85,000 drivers since its launch here in 2014.

The company advertises prominently on billboards around Santiago & through promotional emails as whether nothing were amiss.

Veronica Jadue, the company’s spokeswoman in Chile, insisted Uber was legal. She cited a 2017 Supreme Court ruling that thwarted efforts by Chilean taxi firms & unions looking to halt the service in the northern city of La Serena. The court cited legislation introduced in 2016 by the government of former President Michelle Bachelet to regulate ride-hailing services. “The intention is to regulate it, not to prevent its development,” the three-judge panel said.

That legislation, nicknamed the Uber law, is still pending as the government, powerful taxi unions & app-based startups try to strike a deal.

Jadue declined to confirm whether the company knew that drivers in Chile were coaching passengers to assist them mislead transit officials. “We have stressed the importance of cooperating with authorities,” she said.

A series of scandals has already damaged Uber’s reputation. The company has been excoriated for its frat-house culture, sharp-elbowed commerce tactics & pitched battles with regulators worldwide. While the San Francisco-based start-up has been valued at as much as $120 billion, its growth has slowed. [uL1N20925L]

Clearing up its status in Chile & elsewhere will help. Still, would-be shareholders likely will be more interested in Uber’s ability to preserve its dominance in Latin America & other places where rivals such as China’s Didi Chuxing are moving in, according to Nathan Lustig, managing partner of Magma Partners, a Santiago-based seed stage venture capital fund.

“They’ll be more bothered by market share & whether Uber can be profitable in places…where there´s competition,” Lustig said.

PARKING LOT RENDEZVOUS

In a statement to Reuters, Uber said it is “working diligently” to ensure that ridesharing regulation moves forward in Chile.

FILE PHOTO: A taxi driver holds a flag reading “No more Uber” during a nationwide strike to protest against Uber Technologies in Santiago, Chile July 30, 2018. To match Insight UBER-CHILE/ REUTERS/Ivan Alvarado/File Photo

In the meantime, penalties keep piling up. Since 2016, inspectors from Chile’s Ministry of Transport have issued 7,756 fines ranging from $700 to $1,100 to Uber drivers. Local cops have doled out thousands of citations as well.

Drivers told Reuters Uber reimburses them the cost of their fines to keep them rolling. Uber said it does so “on a case by case basis.”

The company’s technology is helping too. For example, Santiago-area riders had complained on social media that drivers were frequently cancelling rides to & from the airport, a hot zone for citations.

The solution: a special category of service on Uber’s Chilean app known as UberX SCL, named for the code for the Comodoro Arturo Merino Benitez International Airport. Those runs are handled by daring souls willing to run the risk of getting fined, drivers told Reuters.

Securing a driver can be only half the battle. On its Chilean website, Uber instructs passengers who are leaving the airport to meet their drivers in a short-term parking lot. Drivers told Reuters they use the Uber app´s messaging system to switch assembly points whether they suspect quotation writers are hovering.

Uber declined to discuss the reasons for its tailor-made communication in Chile. Spokeswoman Jadue said Uber’s Chile products “are designed to deliver a positive experience to riders & drivers.”

Matias Muchnick, a member of Chile’s vibrant start-up community, said the “chaos” is embarrassing. The country touts its orderliness & sophistication to foreign investors, who might not see the adventure in ducking transit cops after stepping off their international flights.

“People obtain a offensive first impression,” the artificial intelligence entrepreneur said at a December investment conference in Santiago.

But David Brophy, professor of finance at the University of Michigan, said such tales could be a selling point for some IPO investors.

“The key thing is that people want to use it, even though it’s not comfortable whether you´re stopped by the cops,” he said.

EVEN POLICE USE UBER

Uber has tangled with regulators across the globe, including in other parts of Latin America.

In Argentina, for example, the company remains unregulated years after entering the market. Lawmakers in Buenos Aires have largely sided with taxi drivers, who complain Uber charges artificially low fares while avoiding all the overhead born by cabbies.

But the region’s commuters are hooked on the price & convenience, while car owners see opportunity. Uber says it has 25 million active monthly riders in Latin America & one million drivers.

In country after country, it has found success by following a familiar playbook: expand quickly in a legislative vacuum, then leverage popularity & market power to shape regulation.

Still, some local governments are reasserting their authority. In the United States, for example, New York City final year capped the number of rideshare vehicles on its streets. Los Angeles is contemplating a ride-hailing tax to reduce road congestion.

In Chile, negotiations on the Uber Law have been slow.

Taxi unions want lawmakers to limit the number of rideshare drivers & ensure their fares do not undercut those of cabs. Transport startups, led by Uber, have run their own energetic lobbying efforts. Riders have voted with their smartphones; many have little sympathy for “taxi mafias” that long kept prices high & delivered patchy service.

Caught in the middle are Chilean officials. Hutt, the transport minister, admitted publicly that her children used the app & that she had too until she took her post final year. Uber drivers told Reuters that public servants – including police officers – are frequent customers.

Slideshow (3 Images)

In an interview in his Santiago office, Jose Luis Dominguez, the country’s subsecretary for transport, acknowledged his agency’s dilemma.

“(Uber) shouldn’t be operating. Passengers shouldn’t be using it,” Dominguez said. “But…ignoring that it exists would be like trying to block out the sun with your finger.”

Reporting by Aislinn Laing; Additional reporting by Cassandra Garrison in Buenos Aires & Helen Murphy in Bogota; Editing by Christian Plumb & Marla Dickerson

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

#affiiate marketing#article marketing#business online#businessNews#internet marketing#make money online#mobile marketing#video marketing#web marketing

0 notes