#modern fairytales

Text

modern fairytales [little red riding hood] charles perrault

“As she was going through the wood, she met with a wolf, who had a very great mind to eat her up, but he dared not, because of some woodcutters working nearby in the forest. He asked her where she was going. The poor child, who did not know that it was dangerous to stay and talk to a wolf, said to him, 'I am going to see my grandmother and carry her a cake and a little pot of butter from my mother.'”

#perrault#charles perrault#fairytales#brothers grimm#red riding hood#rotkäppchen#literature#moodboard#literature aesthetics#classic literature#literature moodboard#folklore#Modern fairytales

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The time of fairy tales

I’ve got this hugely cool book called “Fairies, elves, dragons, and other creatures of the faerie lands” - which isn’t an encyclopedia of mythical creatures as the title might imply, but rather an encyclopedia of the “fairy fiction” as a whole throughout history, starting with the old Arthuriana and ending at the turn of the millenium fantasy books, passing by Romantic poetry, Tolkien, fairy paintings and.... of course, fairy tales.

There is in particuler one-sub chapter dedicated to fairy tales, called “Les fées s’invitent au salon”, (The fairies come to the salons) written by Terri Windling, which is an informative and excellent recap of the history of “fairytales”, to get a brief but complete introduction. (It however covers in detail only the “ancient” steps, because this sub-chapter is in the chapter of the “Classical times” ; the works of authors like the Grimm brothers or Andersen, while mentioned, are kept for later chapters about the 18th-19th century fantasy). But it still covers in details the history of Italian and French fairytales, lists the big names of the genre, how they came to become a literary genre, as well as how stories for adults ended up becoming stories for children.

Another note: this book was released in 2003, just to put things back into context (because it evokes the “modern” fairytales).

Les fées s’invitent au salon...

Under the term “fairy tales”, we find today any kind of fantasy tale aimed at children. But the fairy tales of today are actually simplified versions of the fairytales of old, re-shaped to fit a child adience - the true roots of the fairytale can be found in the literary salons of the 17th century, where they were created by writers who were authors and editors of adult stories.

A first division should be made: the oral fairytale of the tradition, what one might call a folktale, is different from the literary, “invented” fairytales. Folktales have been transmitted orally since the dawn of time from generation to generation, this is true: they are the tales of fairies, of wizards, of witches, of brave people breaking curses. But the “literary” fairytales were originally an entertainment for an elite, they were a form of art, favorized by the arrival of printing process and by the progresses of literacy. It is true that these literary fairytales are inspired and come from the oral, “rustic”, “folkloric” tales talked above - but they also take inspiration and elements from ancient myths, from famous love stories, and from other literary sources, such as “The Golden Ass” of Apuleius. The authors uses all these things to find the basis, motifs and foundations of their tales, before re-shaping them and re-placing them together according to their own personal imagination.

While supernatural literature is present since the medieval tmes, the true “beginning” of the fairytales as we know them today is 16th century Italy. It is there that the genre started, with two specific works. The “Piacevoli Notti” (The Facetious Nights) of Giovan Francesco Straparola, and the Pentamerone of Giambattista Basile, also known as the Cunto de li cunti (The Tale of Tales). Both authors admit that they took their narratives and their inspiration from the oral folktales of old, but they were not scholars trying to record or preserve an oral tradition and popular folktales - they were writers who were reshaping these tales through the culture and sensibilities of educated men, turning them into literary works aimed at an adult audience. Each of them included their fairytales into a wider narrative structure, imitating the form of the Decameron - and this narrative technique became a classic of the genre. These two works contain the oldest literary forms of many well-known stories today: Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Snow-White, Rapunzel, Puss in Boots... However these stories barely look like the ones we are used to - for example this “old” Sleeping Beauty has the maiden waken up not with a kiss, but by twins suckling her finger, twins she gave birth to in her sleep after the prince “visited” her. The fairytales of those two works were sensual, erotic tales, as well as very dark and violent - the whole sprinkled with crude, vulgar humor. We have to remember that Straparola had to defend himself in front of a court of justice due to his Piacevoli Notti leading to accusations of indecency.

In the 17th century Italian literature strayed away from the marvelous and fabulous, but the tales of Straparola and Basile (Basile more than Straparola) influenced a whole generation of storytellers in France - in Paris. In the middle of the 17th century, fairytales became the new fashion in Parisian salons. These salon, literary salons, were the places where some of the greatest women of letters of the era gained their fame: Madeleine de Scudéry, madame de Lafayette... In these salons, women gained a form of independence, and they could push back many of the barriers that limited them: there, they could let their intelligence shine and practice their talents. Finding a true success, numerous women started writing fiction, poetry and theater plays, and even started earning money thanks to this - allowing some to stay celibate or to split away from their husbands. The salons started to gain a massive influence - they were the ones who started the trends, they were the ones who influenced the artistic concepts and ideals, and they even were the cradle of political movements - each salon offered a web of connections and help for women that fought for their independance. And in the middle of the 17th century, the salons’ new passion was for those word-plays and speech-plays based on the plots and intrigues of the folktales told “by the fireside”. Historically the genre of the fairytale was associated with women, it is true, but the new use the “précieuses” did of it was revolutionary and subversive. Today, their fairy tales seem to us outdated and worn-out, too embellished and ornate, smothered in “pearls and jewels”... But to the ears of the 17th century audience, this baroque language and these overcrowded sentences were truly rebellious, breaking off with the polished, restained, dry style of the literary works approved by l’Académie française (of which women were excluded).

In fact, fairy tales played a big role in the socio-literary feud known as “la querelle des Anciens et des Modernes”: on one side, the “Ancients” believed and claimed that a great work of literature could only be derived from Latin texts or Greek stories, they imposed the idea that anything worthy and all culture came from the Greco-Roman heritage. On the other side the Moderns, of whom Perrault was a leader, considered that a new literature was possible, a literature coming from the past, culture and tradition of France itself - and the fairytales were the emblem of this “Modern” literature, breaking away from the old epics of Antiquity to rather create a literature out of French folktales. The baroque style of fairytales also played another very important role: it hid their subversive subtexts, and it allowed them to be published despite the presence of a widespread censorship on literature. It is no surprise that these women writers depicted young girls born out of aristocracy living under the arbitrary control of a father, a king, or an old and wicked fairy; Similarly, it is no surprise that it is fairies full of wisdom that arrive in the story to bring an unexpected happy ending. It was due to the omnipresence of “fairies” of these tales that they were called at the time, “fairy tales”, “contes de fées” - the name that now defines the genre today (even though at the time it only designated the French literary works of the salons, it now designates a vast and sprawling corpus of international supernatural stories). However the fairies that lived in the salons and in these literary tales were quite different from the creatures of oral tradition and old myths. They had several common features: like them they practiced magic, like them they granted wishes, like them they could do either good or evil, like them they could help or curse people... But these new fairies were clearly belonging to the nobility, they were intelligent and educated fairies, with a strong independence: they were fairies ruling over entire kingdoms, they were fairies taking care of justice matters, they were fairies influencing fate itself. In a way, these fairies embodied and reflected the women-authors that created them.

As the fashion of the fairytales continued throughout the 1670s and the 1680s, madame d’Aulnoy proved herself to be the most famous of the Parisian storytellers, admired by all as much for her stories as for the brillaint and important friends she had. She ended up writing down her fairy tales (such as The White Cat, The White Doe, The Blue Bird, The Sheep) and publishing them in 1690 - they were enormously successful, a true best-seller. Soon after, author famous members of salons started publishing their own fairy tales: in 1695 Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier and Catherne Bernard, in 1696 Charles Perrault and the comtesse de Murat, in 1697 Rose de La Force, in 1698 Jean de Préchac and le Chevalier de Mailly, in 1699 Catherine Durand, in 1701 the comtesse d’Auneuil... The salons were also frequented by men - non-conformist men, men supporting the Moderns. Three of them deserve a mention here: Jean de Préchac, who wrote the “Contes moins contes que les autres” (an impossible to translate wordplay that I could vaguely assimilate to “Fairytales less fairy than others”) ; Jean de Mailly, author of “Illustres Fées, contes galants” (Famous Fairies, gallant tales), and Charles Perrault, who created “Histoires ou Contes du temps passé” (Stories or Tales of the past), also known as “Contes de la mère l’Oye” (Tales of Mother Goose).

Born in Pars in 1628, Perrault was part of a family belonging to “la noblesse de robe” (the nobility of the dress - there were two types of nobility in France, the “nobility of the sword”, the old nobility who earned their title through warfare and military ; and the “nobility of the dress”, new nobility who earned their title through administrative and bureaucratic work); His father was a magistrate who was part of the Parliament, and his four brothers had shining careers in theology, architecture and the law. Charles hmself was magistrat for three years after studying the law at Orléans, he then became the “senior clerk of the State”, aka the secretary of Colbert (the sort-of-prime minister of king Louis XIV). He wrote poetry, essays and speeches glorifying the king, and he was elected at l’Académie française in 1671. In 1672 he married Marie Guichon: they had three children, Marie died of smallpox a few years after, and he never wed again. In the 1690s, Charles Perrault took an interest in fairytales. He wrote three poems inspired by folklore (later known as his “Fairytales in verse”), he then wrote a prose tale which was the prototype for his future “Sleeping Beauty”, and finally he published “Histoires ou Contes du temps passé” uner the name of his son, Pierre Perrault Darmancour, in 1687. (It is a whole topic I will explore another day). Perrault took back the tales of the oral tradition and the folklore, but removed their rudeness and “rustic” aspect to made refined, courtly, aristocratic tales, filled with humor and “lightness of spirit”, but behind which his defense of the Moderns was very clear. These stories were notoriously different from the fairytales written by the women o the salons - Perrault’s style was much simpler, his stories less complex, and his speech less baroque. He rather wanted to give the artificial feeling of having fairytales directly taken from the mouth of an old peasant storyteller of folktales, the famous “Mother Goose”-type of character. The second difference relies in his treatment of female characters, as his princesses are much more passive and defenseless than those of the other fairytale writers, their main vertues being beauty, modesty and obediance.

Even if the women of the salons, like Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier and madame d’Aulnoy, were just as much read as Perrault, the literary critics viewed them more badly: they preferred much more Perrault’s tales, due to them being supposedly much simpler and less subversive. In 1699, the abbé de Villiers wrote a “Dialogue” in which he praised Perrault but heavily criticized the women who were writing fairytales - he was so furious of their success and popularity that he claimed most women only liked to read because they wanted a trivial way to be slothful, he also added that anything needed a bit of effort tired them and bored them. If one was to trust his words, for them a book was just a game and ornament, not much more than a ribbon.

The social and literary terrain gained by women actually started to get away from them in the 18th century. The salons closed one after the other. Perrault died in 1703, d’Aulnoy in 1705, Bernard in 1712. This era saw the arrival of a “second wave” of fairy tales in the literary landscape of France. This time, it was stories mostly written by men, actng as both parodies of the previous fairytales, as well as new stories inspired by the folktales and myths of the Orient. This second wave started with the enormous success of Antoine Galland’s translation of Les Mille et Une Nuits (One Thousand and One Nights) introduced the Arabian fairytales to the French audience. Galland, an orientalist, had discovered throughout his travels a 14th century manuscript while he was trying to translate the tale of Sinbad’s travels and journeys for one of his former students. Today, his translation is heavily criticized for taking numerous liberties with the original material, but one has to remember that Galland wasn’t trying to create a scholarly, university-level, faithful text: he wanted to make France discover an entire world unknown to it. The One Thousand and One Nights flooded France, inspired numerous pastiches of Arabian tales, from the Adventures of Abdallah by l’abbé Jean-Paul Bignon to “La Patte de chat” (The cat paw) by Jacques Cazotte.

In the middle of the 18th century, a “third wave” of fairy tales happened in France. These new writers were closer to the “salonnières” of the 17th century, much more than the parodists of the “second wave”. For example Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve created stories quite similar to those of the 1690s, in which she also studied the role of women in the marriage and in society. In her youth, she had been the wfe of an army officer whose death had plunged her in poverty, and forced her to live from her writings. Her most fairytale is “Beauty and the Beast”, a long, complex and subtile erotic story that explores questions of love, marriage and identity. The story was then rewritten in a shorter form by madame Leprince de Beaumont, who created the most popular form of this tale today. Another author that took back the tradition of the old salons was Marguerite de Lubert, who wrote six successful novels based on fairytales, and numerous other shorter texts. Her most famous stories are “La princesse Camion” and “Peau d’Ours”. Just like Marie-Jeanne l’Héritier and Catherine Bernard, she avoided any marriage in order to be entirely dedicated to her literary career.

In the second half of the 18th century, a new iea appeared: why not adapt fairytales to young readers? Until now, the literary for children was a boring, didactic one, all about teaching moral values. Ad now, parents and teachers with a more open mind start thinking that maybe moral will be easy to swallow if it is wrapped in the “sugar of entertainment”. Madame Leprince de Beaumont was one of the first French authors to write fairytales fit for children. She had fled an unfaithful, dissolute husband, had lived in England as a governess, and started writing French fiction for journals destined to “young ladies”. Even if her fairytales contain some original elements, it is clear she took most of her materials from the previous authors of the genre. All throughout the 18th century, the fairytales of madame d’Aulnoy, Charles Perrault, comtesse de Murat, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier, Catherine Bernard and Rose de La Force were published in “La Bibliothèque bleue” (The Blue Library), a collection of small and cheap books spread by peddlers. Written for lower classes and lesser social groups, these rewritten, simplified tales had a huge success - and the fact that they were often read out-loud to illeterate group caused a strange phenomenon: these literary tales slowly returned to, fused in the oral culture of France, and een of other European countries. This is why a lot of people, still to this day, believe that Donkey Skin, The White Cat or Beauty and the Beast are anonymous, folkloric tales.

These oversimplified, sometimes anonymous, versions of the fairytales could have been the only ones we kept today, if it wasn’t for the huge, colossal work of the writer and editor Charles-Joseph de Mayer. From 1785 to 1789, he published 41 volumes collecting and compiling a hundred years of French literary fairytales: it was the Cabinet des Fées. Afterward, century after century, a hierarchy formed itself in popular culture and the mind of people, a hierarchy that summarized the entirety of the history of fairy tales in three texts: the fairytales of Charles Perrault, the fairytales of the brothers Grimm, and the fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen. It is only quite recently that the wider history of the genre is brought to light, thanks to the works of several “historians of fairytales” such as Jack Zipes, Elizabeth Wanning Harries, Maria Tatar, Lewis C. Seifert, and Marina Warner.

At the dawn of the 21st century, many more fairytales are being published - returning to their original status as “tales for adults”. Some are new stories imitating the same themes and narrative techniques as the fairytales of old, others are retelling of old stories in more subversive forms, often as a way to explore and criticize modern society or the question of genders. The article concludes on a list of these new “fairytale storytellers”: Angela Carter, A. S. Byatt, Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Kathyrn Davis, Olga Broumas, Carol Ann Duffy, Liz Lochhead, Emma Donoghue, Berlie Doherty, Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman, Tanith Lee, Midori Snyder, Patricia A. McKillip, Kate Bernheimer, Robert Coover, Salman Rushdie, Neil Gaiman.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#history of fairytales#literary history#literary fairytales#charles perrault#modern fairytales#italian fairytales#french fairytales

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This is the thing about fairy tales: You have to live through them, before you get to happily ever after. That ever after has to be earned, and not everyone makes it that far. There are stories where you must wear out your iron shoes to right a wrong, where children are baked into pies, where jealousy cuts off hands and cuts out hearts.

We forget, because the stories end with those ritual words—happily ever after—all the darkness, all the pain, all the effort that comes before. People say they want a fairy tale life, but what they really want is the part that happens off the page, after the oven has been escaped, after the clock strikes midnight. They want the part that doesn’t come with glass slippers still stained with a stepsister’s blood, or a lover blinded by an angry mother’s thorns.

If you live through a fairy tale, you don’t make it through unscathed or unchanged. Hands of silver may be beautiful, but they don’t replace the hands of flesh and bone that were severed. The hazel tree may speak with your mother’s voice, but her bones are still buried beneath its roots. The dead are not always returned, and roses do not always bloom from graves.

Not every princess climbs out of her coffin.

Happily ever after is the dropping of a curtain, a signal for applause. It is not a guarantee, and it always has a price."

Kat Howard, Roses and Rot p. 288-289

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

the 2 flavours of my OCs: short, curly-haired cutie and long, black-haired emo introvert

#oc#oc art#original character#character art#character illustration#red riding hood#modern fairytales#modern fantasy#worldbuilding#artists on tumblr#digital art#illustration

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In America, Mama had said, they don't let you burn."

as someone who devoured books in her teens and is now almost incapable of sitting down and reading a book, I've decided to challenge myself this summer to reading at least a book a week. they have to be books I haven't already read, and they have to be written by either women or POC.

I have a good list going already, but figured I'd start with one that's been on my to-read pile much longer than I care to admit. it's a collection of short stories of modern mythology/fairytales. it contains a retelling of anderson's horribly sad matchstick girl, in the setting of the historic matchstick strike in 1888 when women were dying of phosphorus poisoning from working in the factories. there's also a retelling of the twelve dancing princesses, which is one of my personal favorite fairytales.

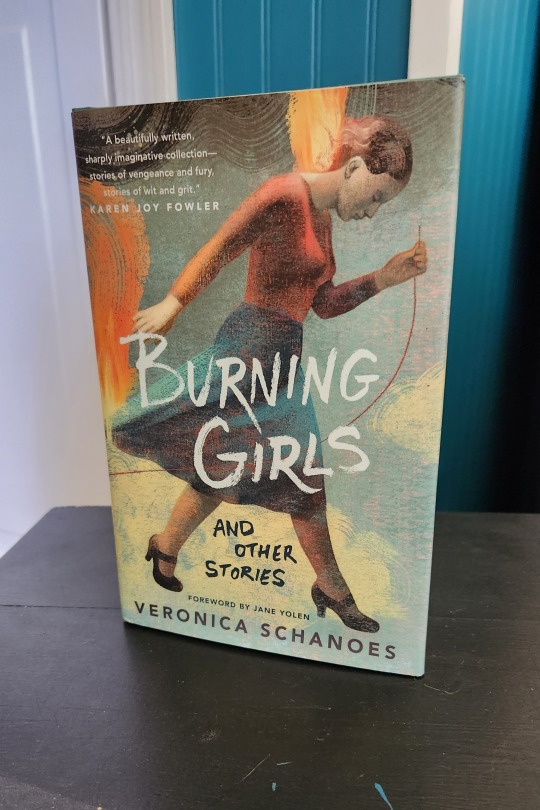

i'm only partway through Burning Girls and Other Stories, but I have enjoyed every word of it so far

[Image: the cover of Burning Girls and Other Stories, by Veronica Schanoes]

#Bookclub#Summer reading#Burning girls#Veronica schanoes#Modern mythology#Modern fairytales#But also historical oppression and xenophobia#And women who are allowed to be angry and get revenge and make their oppressors suffer#Read more books 2023#book recs#book recommendations

0 notes

Text

with all the negativity Disney's wish has received lately it genuinely feels like people are just looking to hate one something. Disney gets critiqued for not making original stories. So They make a princess fairytale movie. Disney gets critiqued for not having evil Disney villains. They give it an evil Disney villain. Disney gets critiqued for having overcomplicated plots. They make a sweet little movie about wishing on stars. But then it's "too safe" the villains evilness is "forced" and the movie is "self indulgent" for all its references even tho it's literally Disney's 100th anniversary movie.

Do y'all just not know how to enjoy things like a classic Disney fairytale movie without only seeing what you'd rather it be? Wish was a fun, sweet, cute little movie but because it's not the greatest film they've ever made it's a "disappointment"? Idk it feels like Wish is being held to a way higher standard then all of their other films from the last 5 years and after seeing the film I just don't see what's got y'all this upset.

#and to be upfront I do not like Disney as a company#But Wish was just a good movie to me being a classic fairytale and I think it's actually refreshing to not be too deep and modern for once#King Magnifico is the best Disney villain in 12 years yet everyone just wants to complain#Wish#Disney wish#Wish movie#princess asha#Disney

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art by Shannon (momhugssss)

#painting#artist#art#artblr#oil on canvas#oil painting#modern art#iridescent#contemporary art#weirdcore#dreamcore#liminal#liminal spaces#fairycore#fairytale#fairytales#religious painting#religious imagery#religious art#ai generated

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

I read a kakaobi fic yesterday... OMG.

for love of a boy by revecake. Based on Yukio Mishima's The Sound of Waves. One word: masterful.

My art does not depict a specific scene from the fic, it's just something inspired by its mood! Obito's appearance is not fully fic-compliant.

Just look at these various quotes:

from the water, kakashi rises and rests his arms on the edge. a tilt of his head, his wet hair falls, pooling silver on obito’s boat, and when obito looks, looks with a certain haze across his eyes, kakashi becomes the mystical half-fish of his dreams.

kakashi smiles, and the plain beauty of his naked face is perfectly real. “it’s a good catch today, isn’t it?”

“kakashi-kun?” his father laughs, an exasperated turn of his brow. he continues to trace his blade under the skin of tuna, and another piece of flesh comes butterfly-free, as light and pink as a sakura petal floated from the island’s schoolyard to the sea.

the rain blurs for a moment, and the sight through the dripping leaves is akin to a sheen of sun being thrown from the sky. dazzling, a celestial maiden’s robe has been haphazardly tossed from the heavens to be muddied as a damp blessing across the fresh ground.

when he’s finished, the only curtain to his nudity are the wet clothes draped and swinging from the window pane.

they balloon and deflate in the imitation of a body in the wind, but as obito rises, stretches, strides towards the bedroom, the shape of his shoulders and back leaves a solid impression through the wet glass. he doesn’t need to wash, not when the sun has already bathed the lean lines of him in dry heat.

dreams are only fading things, passing on waves, caught in the wind, melted into dew by the morning.

obito looks up at that pale face, and what he sees - he wraps his hands around kakashi’s wrists to keep him there.

how can he say this?

how does he give language to his desire, how does he make kakashi understand his earnesty in this very moment?

he cannot let it become an untranslatable disappearance, as so many dear things are, have been lost to sea.

#fic rec!#READ IT#narutoart#i was moved#this is pure poetry#kakashi#obito#uchiha obito#hatake kakashi#kakaobi#obikaka#obkk#kkob#fanfiction#i'm not a fan of modern-ish aus#but this one!#it immerses you into a fairytale#shikamaru makes the best cameo appearance#revecake

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my god. What is with Disney these days? No one wants a “woke” Princess and it’s like they don’t even understand the word anyway.

Pixar does because look at Merida. She still got help from “a man” even if they were her little brothers. It was still “female empowerment” because her mother is actually the one who killed the bad guy anyway and it was because he was about to kill Merida. It wasn’t just “women strong!”. Hell, Merida refuses to get married and actually ends the movie that way but she never comes across as “ew, men” but that she simply doesn’t want to. I can relate.

But back to Disney. They changed Little Mermaid so Ariel literally did EVERYTHING including killing Ursula despite the fact that she shouldn’t even know how to drive a damn ship. 🙄 There was nothing wrong with Eric doing it!

And now we’re getting “woke” Snow White who is named as such because her skin is WHITE AS SNOW! But noooooo… she has to be a person of color too so Disney can have lazy writing and call everyone racist when we call them out on this BS. POC are just shields for them now although Rachel Zegler tried to accuse everyone of hate already. Lady, that’s not going to get people to see your point. And frankly, it’s not even about her. It’s about Disney and what they’re doing.

Also they’re apparently planning to change the Prince coming in to wake her up at the end. Like, what? And most of the seven dwarves are gone too. I think there’s only one now while the others are “normal”. They thought(and Zegler said) that the Prince was “acting stalker-ish” so that’s why they wanted to change him. Hah. They clearly didn’t watch “Once Upon a Time”. Now THAT is a live-action Snow White.

Plus there is a “deleted scene” comic which explains how the Prince even knew to come looking for Snow White. He was captured and locked up by the Evil Queen and witnessed her transform into the hag and poison the apple. He immediately went to find Snow when he managed to escape. All the live-action had to do was include something like this and then he isn’t “stalkerish”. 🙄

Frankly, their movie is not even Snow White anymore and I can tell already that it’s going to flop with all these unneeded and unnecessary changes. All it shares in common now is the name. Nothing else.

This is just my opinion. You don’t have to agree.

#I can’t even anymore#anti 2024 Snow White#Disney should be ashamed#they obviously don’t care though#anti disney#this is not ‘modernizing’ the princesses#or their stories#the stories actually are fairytales from different countries#and not creations of Disney anyway#my opinion#my rants

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustration from Andrew Lang’s The Olive Fairy Book by Kate Baylay (2012)

#kate baylay#art#illustration#modern art#2010s#2010s art#contemporary art#english artist#british artist#books#book illustration#childrens books#fairy tale#fairy tales#fairytale art#andrew lang#art deco#classic art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

if you make a period drama or fairytale retelling with queer or trans characters but nothing especially 21st-century about it

and then call it "updated" or "modernized"

you owe every LGBT person $500

#lgbt#gay#queer#period drama#fairytale#queer history#we are not inherently modern!!!! we have always been here!!!!#you are contributing to the attitude that queer/trans people are A New Thing!!!!

561 notes

·

View notes

Photo

modern fairytales [the seven ravens] brothers grimm

“She walked on and on - far, far to the end of the world. She came to the sun, but it was too hot and terrible, and ate little children. She hurried away, and ran to the moon, but it was much too cold, and also frightening and wicked, and when it saw the child, it said, 'I smell, smell human flesh.’”

#grimm#brothers grimm#fairytales#seven ravens#the seven ravens#die sieben raben#literature#moodboard#literature aesthetics#classic literature#literature moodboard#modern fairytales#folklore

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading “Contes de loups, contes d’ogres, contes de sorcières” by Eva Barcelo-Hermant, is a bit disappointing because its title is “The making of villains” and promises a study of the villains in fairy tales and looking at their origins... and it doesn’t really do that? It basically flies over the villains with the simplified typology I just talked about before, and it quickly brushes the topic aside - so that’s disappointing...

But what is interesting is that Barcelo-Hermant shares her insight and the info she collected by working inside publishing houses and editors of youth literature in France (coupled with some psychology and sociology books she read) to explain a bit the situation of the fairy tale in today’s France, among youth literature and... it is not a very optimistic one.

According to Noël Daniel, there was in France a great era of printing and publishing of traditional fairytales and new fairytales: 1850-1950. It was the time where huge collections of fairytales were published, were there was still a lot of publications directly taken from the original sources, new content and collected tales... And then, past the 50s, we entered a new era where publishing houses for kids rather focused on released “rewrites” of the classical fairytales, books which take fairytales known and love, but have another author slightly or massively rewrite them, and where the focus is placed on having specific authors illustrate those fairytales to make a true “graphic novel”. And there is a true paradox here... Fairy tales are still massively popular - such as Little Red Riding Hood which keeps getting reprint on reprint, rewrite on rewrite... Every publishing house for children needs to have at least one classic fairytale in its catalogue. And when it comes to authors and illustrators, it becomes almost an iniation rite to rewrite or illustrate a fairytale - it is a sort of exercice of style, where they can offer their own sensibility, their own look, their own perception of the text. This is all there... But at the same time, today people are not enthusiasmed or passionate about fairy tales anymore, which is coupled with a true will to change and renew these stories until they get further and further away from their original source.

In fact, some parents outright refuse to read fairytales to their children. There is a true backlash recently against fairytales, and it is just a paradox as what I said above: because on one side you have parents who claim fairytales are too violent, too misogynistic, too brutal and too dark for children... and on the other you have parents who rather claim that fairytales are too idyllic, too simple, too archetypal - they notably criticize the happy endings, that they deem too irrealistic, they claim these tales are naive and too idealist. But the problem is that, as Barcelo-Hermant puts it, it is the very nature of fairytales. Peyrache-Leborgne explained that it is a fundamental trait of the fairytale: it is a dramatized oxymoron filled with powerful contrasts. It is most revealed into the brothers Grimm fairytales - and this is one of the reasons of their success. These tales keep alternating between opposite tones: they are both violent and sweet, they are cruel and yet empathetic, they are pathetic and yet have a happy ending - the brothers Grimm knew that their tales were at the same time very dark, and yet utopias. (The source for that is “Violence et douceur des contes de Grimm”, Violence and sweetness in the Grimm fairytales, from “Vies et métamorphoses des contes de Grimm”, “Lives and metamorphosis of the Grimm fairytales”).

So, if we follow the logic of these parents above, it is the very writing, the very essence, the very format of the fairytale that should be re-done entirely. Even though, as the author points out, the problem isn’t the fairy tales in themselves, but the fact that they aren’t adapted to our modern times - the true criticism of these parents is the fact these fairytales feel unadequated with the modern world. The parents deem these stories too violent, because they fear it will traumatize their children. They deem these story too idyllic, because they don’t want to give their children the idea of “having endings that are not deserved” or to give them “passive young girls” as role models. To exemplify this, the book mentions the case of a writer named Aurélie Tramier, who in her book “Peindre la pluie en couleurs” (2020), told an anecdote of hers: her niece had asked her to read “Little Thumbling” by Charles Perrault. Her aunt agreed, but upon reading the story was shocked by how “sordid” it was. She deemed that Charles Perrault was a “macho” writer, who only wrote female characters that were either “stupid, witches or brainless”, fainting left and right for no reason. She ended up stopping the story mid-tale, refusing to read its conclusion because she didn’t want to give her niece nightmares.

In front of this reaction, Barcelo-Hermant reminds her readers that the tales of Perrault and of Grimm were not originally meant for children - and while ever since the 19th century they are considered exclusively as children’s literature, most agree that these tales shouldn’t be read to children who are too young. She also notes how the modern censorship of fairytales is just a continuation of the same censorship of Perrault and the writers of his times, who already had removed from the folkloric tales their most violent elements - take Little Red Riding Hood, where the sexual elements were kept, but the episode of the “cannibal meal” was removed. The book mentions a modern version of “Doneky Skin”, released in 1902 by Casterman, a “Catholic” version of the tale rewritten by Pierre Féron. And in it, Pierre Féron removed the incest element by turning the titular Donkey Skin into a random sheperdess that the king wants to marry at all costs. But by removing the key element of the tale, its very structure is changed - because in this retelling, we do not know why the king selects this shepherdess, or why he is so insistent on marrying her right after his beloved wife died.

Interestingly, this modern censorship of youth’s literature isn’t just for fairytales, but with all the books for children. Annie Rolland noted that in today’s youth literature, violence under all its forms is removed. You don’t find mentions or talks of war, of death, of suffering, or of the violence of human relationships, nothing about sexuality, nothing about desires, nothing about feelings. By removing all that, one of the key aspects of literature itself is removed: that is to say, making the reader think about the fundamental principles of human life, the main aspects of the human existence. It is also a censorship that relies heavily on moral, philosophical and religious concepts and ideas, while rejecting any scientific approach or discovery. Hopefully, currently a lot of book series for children currently manifest this desire to explore the various topics and aspects of life, answering questions about society and existence - they even start to touch harsh and difficult subjects, through metaphors, which is noted to be a good thing. Because this censorship basically removes what makes the child think... The basis of this censorship also reveal itself when you look at “Hansel and Gretel”. When you look at this story, you’d think it would be heavily censored - it includes extreme poverty, the threat of famine, parents abandoning their children to die, animals treat like cattle to be slaughtered, a cannibalistic witch, the murder of an old woman by an oven... And yet, Hansel and Gretel escapes this entire censorship process. Why? Because 1) The wicked mother being turned into a “wicked step-mother” softens the familial violence, and thus doesn’t make it appear as shocking and 2) the punishment of the witch is perceived as something deserved, and thus a manifestation of justice. With this “moral” approach, a fairytale like Hansel and Gretel is allowed - but a fairytale like Donkey Skin could never be written today. In fact, a lot of people fear of writing new fairytales - they prefer sticking to the old tales, re-doing them again and again, because they have a certain “authority” to them.

Barcelo-Hermant had an interview with a member of the Didier Jeunesse publishing house, around the release of a book called “La jeune fille et le hibou” (The girl and the owl). This book, written by Catherine Pallaro and illustrated by Anouck Fontaine, was a rewrite for children of Grimm’s “The maiden without hands”. But when doing this rewrite, they had to change the original title, out of fear it would seem “too violent”. But even then, the book still shocked, especially the cutting of the girl’s hands (here done by her brother rather than her father).L In fact, during this interview, the member of Didier Jeunesse revealed that, due to fairy tales shocking a lot today, they seriously wondered if they should continue publishing them, or just stop. She noted that our sensibilities and our ideas when it comes to fairy tales have changed a lot - and she doesn’t know if it is a bad thing or a good thing. But what she noticed for sure is that people have less and less a “culture of fairy tales” today: either they knew very little of fairy tales, either they only know them through Disney.

Another experience, this time lived by the author of the book herself, as she was working in a publishing house, as receiving a very angry mail from a parent due to a certain gift... A child had received as a gift, from his grandparents, the book “Pinocchio”. And this angry parent was shocked upon seeing the illustrations: one with Pinocchio being hanged, another with a coffin getting prepared for Pinocchio if he doesn’t take his medecine, a third about Pinocchio turned into a donkey and beaten up with a whip... This parent clearly said this story was not adapted to children, was angry at the fact there was no warning and no age limit on the book, and they wanted to have a chat with the publishing house to talk further of this problem.

Publishing houses today have a real difficulty when it comes to promoting or publishing fairy tales that are either 1) not well-known or 2) different from the “canon” Disney created. This is notably why Didier Jeunesse wondered if they should go on, as their publishing house focused on unusual, different fairy tales. They wondered if they should continue publishing fairy tales, if they still please people, if there is still an audience or an interest for them. The publishing house (but others too) seriously wonder about this, because fairytales are perceived now by the audience as old-fashioned and ancient. More interestingly, there is a double “critic” that is often raised up against fairytales. 1) They are not feminist stories. Feminism is the big thing, the big trend in youth literature today, and the audience dislikes fairy tales because they depict women, have a vision of female characters that are not corresponding to modern sensibilities. 2) Fairy tales are “elitist”. It might seem strange for you to read that, but it is a true complain modern French parents have towards fairy tales: given there is a lot of text, parents note that it is difficult to read it to a youn child, and they also tend to complain that, due to these stories being conceived in olden times, they do not bear interest for young children today. Too complex and too old: people claim fairy tales are “elitists” stories. It is a paradox that one of the interviews editors tries to explain: yes, these stories come from older times and a now-gone society, and no the characters are obviously not what one would want to teach their daughters about today - they would prefer much more active characters... But there is the very important fact that these stories are not of the real world, they are not stories of reality. They are stories from the imaginary world, stories out of imagination, and so they need to keep an archetypal feeling to them, they need to have a cathartic aspect since they are NOT reality.

Nowadays, to better sell a fairy tale, you have to go one of two ways. 1) You must put forward the bravery of the female hero, or the cunning of the male hero. 2) You need to put forward the villain but ONLY if it isn’t a real villain. Another thing that today’s mothers (especially on the Internet) are easily shocked by, is when the villain or antagonist is deemed “too strong” or “too terrifying”. Parents prefer villains that are only “temporary villains”, that are “healed of their evil with the right words or right gestures”, or a character who became evil because of a “cute or funny reason”, or if their evilness is something more easily relatable, like a fear and distrust of others. It comforts these parents, because their main concern is, again and again, to not traumatize their children. They prefer today brave and clever heroes escaping their situation through cunning, and for that want to sacrifice the idea of big villains that could harm children.

Fairy tales today in France, when re-edited, are always rewritten by other authors - it is almost impossible to publish the original editions or versions of the texts. They are still recognized as part of the literary culture, part of France’s patrimony, and while the editors admit that yes, children are not made of sugar and won’t break like twigs in front of such stories... they also have to stick to rewritten, softened, remade stories due to how hard it is to publish the stories in their oldest forms. But hopefully, unlike the editors and the publishers, most authors and playwrights, keep clearly insisting that a story needs a real villain, because the important thing is to show how one can overcome the monsters, how one can vanquish them. We cannot shield away the children from the world - and when one shares the world with children, they must share it in its entirety, good and evil. The children must be accompanied as much in pleasant as in difficult times - and the fairy tales are here for that. Real villains are needed to show that, despite all hardships, people still have the right to be happy, and they still have the right to create the end of their own story.

Eva Barcelo-Hermant also pointed out the paradox of how parents insist on sanitizing fairytales out of an obsession for “not scaring” and “not traumatizing” their children... And yet, when you go in any school, when you look at any playground, children are very nasty and very cruel to each other, sometimes to heart-breaking degrees. The defenders of fairytales point out that telling children scary and frightening tales allows kids to exorcize the nastiness within them, or offers them tips and keys to help them facing certain situations. The author quotes Joëlle Turin’s “Ces livres qui font grandir les enfants” (Those books that make children grow up) when writing the rest of the chapter: The monsters of fairy tales - the wolves, the dragons, the witches, the snakes - are manifestations and symbols of the fear of children: fear of the dark, fear of the night, feark of being abandoned, fear of the stranger, fear of the other place, fear of the mystery... And in this “poetic space”, they can explore their fear, challenge them in a mental landscape, and vanquish them, or displace them towards other content - they build up defenses against them. A perfect example of this system is the “double tale” of Little Red Cap, by the Grimm brothers. When the second wolf arrives, Little Red Cap learned her lesson from the first story, and she does everything she has to do to vanquish the beast.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#french fairytales#fairytale villains#french stuff#book reference#fairytales today#modern fairytales

0 notes

Text

#lee pace art#lee pace#leeepfrog#thranduil#modern day thranduil#the hobbit#the elvenking#tolkien#king of the woodland realm#the king of mirkwood#fantasy art#thranduil art#fantasies#fairytales

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rosaline (2022)

#Rosaline#Rosaline 2022#Rosaline Hulu#Romeo and Juliet#Kaitlyn Dever#Kyle Allen#Sean Teale#Isabela Merced#period drama#perioddramaedit#periodedits#my gifs#one disappointment after another#first Birdie then this X_X#(and many more before them - it's just that these two premiered this month)#even taken as the simplest modern oops-forgot-the-magic fairytales#with no pretence to have a single decent joke#such films are so shallow it's unbearable#...so now I'll go rewatch Upstart Crow 1x01 for the hundredth time#because comparing to this nonsense UC is an utter masterpiece with profoundest irony#and UC take on Romeo and Rosaline is better even without any Rosaline on screen

780 notes

·

View notes

Text

did we all collectively forget that vampires not being able to see their reflection because old mirrors were backed with silver is a tumblr creation that has no basis in any classical texts or?

because the reason vampires cant see their reflections (in classic texts) is because mirrors were considered reflections of the soul, and vampires are soulless, which means regardless of what the reflective surface is, they cannot cast an image.

i'm not a snob, i love modern vampires as much as classic vampires, but please remember that classic vampires are soulless monsters, not misunderstood sadboys of the 00s>.

#charlie.txt#i just saw an astarion headcanon but the way it was worded it was like this was canon lore#it was a harmless hc tho so i didnt want to harass op with nitpicking#but for one dnd5e (and be extension bg3) has its own set of vampiric lore#and for two the silver thing isnt based on any pre established lore in any mainstream media like. ever.#afaik.#they either cant see their reflection or they make a snarky comment about how you shouldnt believe all the fairytales#those are the two modern options in mainstream media#this isnt like. serious. im not upset.#THATS A LIE IM IRKED LMAO.#i just like vampires lol but im not like. stewing abt it.#its my silly little topic im passionate about.

85 notes

·

View notes