#mircea cărtărescu

Text

Alla mia tristezza erano caduti i dentini da latte

in cambio era cresciuta tanto che non potevo tenerla già piú nella tinozza

si spennava orribilmente e tutta la casa si riempiva delle sue piume iridate

le aspiravo profondamente e tossivo, vere crisi d'asma.

In breve aveva messo su mascelle da coccodrillo e le erano spuntate zanne da tigre

e mi seguiva dappertutto lasciando filamenti di bava sui tappeti

dormiva nel mio letto, sul mio torace, e faceva tremare tutto l'edificio quando lei russava.

Tale tristezza mi straziava la pelle della schiena, aveva ficcato un artiglio dentro di me

e mi manipolava come fossi una marionetta ringhiando.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suddenly he was in my cabin, naked, with butterfly wings between his shoulder blades, his penis erect, powerful and golden, his dog tags on a silver chain around his neck. I clung to him and everything became luminous, fabulously colored, as though we had entered the mystical aura of a chakra with dozens of petals. When he broke my seal, he inserted in the center of my abdomen not only an ivory liquid, but also complete knowledge, as though his cannula of supple flesh had become a cord of communication between our two minds, through which, in a flash, we said everything to each other, we knew everything about each other, from the chemistry of our metabolisms to our complexes, preferences, experiences, and fantasies.

(...)

We both rose and fell, and neither of us had memories or a life of our own. We had come into the world (but which one?) only for the moment of our coupling, like two insects, in a halo of concentric circles of light. And that was how we would always be: standing, stuck together, united above in our gazes and below by that seminal cable, through which I felt millions of bits of information invading me.

Mircea Cărtărescu

Blinding (1996)

#mircea cartarescu#books#mircea cărtărescu#blinding#book quotes#lit#literature#books & libraries#books and literature#quotes#couple#romantic#lovers#fantasy#insects#butterflies#butterfly#wings#surrealist#fiction#surrealism

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solenoid

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I have often thought I should go back to that neighborhood, where I spent my childhood among the sweetness of roses taller than me, reading on the windowsill with my legs hanging out. I thought I could go see the street with the musician’s name, the grocery, the militia station, and the clinic, not realizing you can’t revisit the imaginary neighborhood dug into the soft stone of your mind, but only the one made of brick, debris, and plaster, the one with the chestnuts that indifferently bear their spiny fruits in autumn. The neighborhoods of childhood exist nowhere on Earth. And still, I said to myself more than once: I should go there anyway. I should use the present-day buildings, clouds, and trees to project shadows onto my unshielded, sensitive brain, and perhaps in the play of their shadows I will recognize something from that time."

Solenoid, Mircea Cărtărescu

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Reading

SOLENOID

Mircea Cărtărescu

Translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

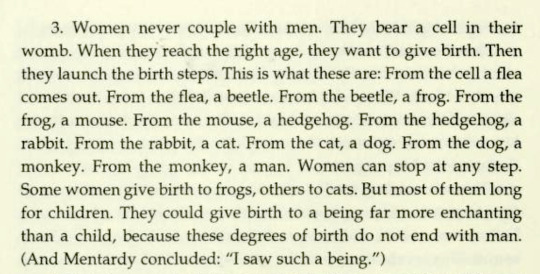

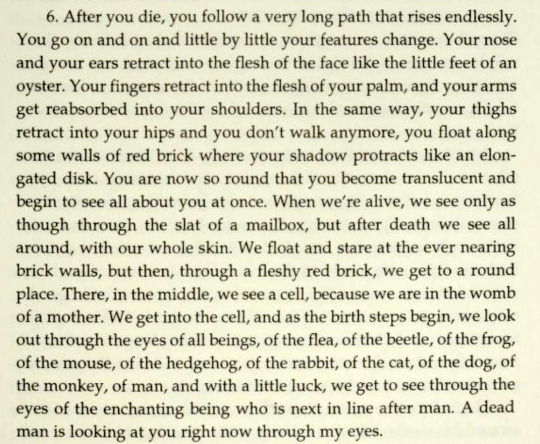

mentardy's theories from Mircea Cărtărescu's Nostalgia

#fav#I will never understand why this book isn't more popular#It changed me deeply#fav ever#Mircea Cărtărescu

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Caută-mă!", auzeai chemarea ei tânjitoare, „caută-mă chiar şi-n trădare, chiar și-n păcat! Caută-mă chiar și-n deplină uitare! Toceşte nouăzeci și nouă de opinci de fier şi-un toiag de fier până ce vei ajunge la inima mea...".

— Mircea Cărtărescu, Theodoros

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[improvised translation:

photo 1: i am unwell / i was deeply hurt / then i hurt myself / even worse / i was waiting for something from you / and you hurt me / even deeper

photo 2: self and being / is the same thing // and // the same thing / as pain]

-- Mircea Cărtărescu, Nu striga niciodată ajutor (Never cry for help)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's my birthday today, which always feels like a time to take account. The last month or two, I've endeavored to channel spates of low mood into the reasonably productive activity of reading, rather than mere vegetation, and I've had good success. I just finished Mircea Cărtărescu's Solenoid—a long novel about a lonely weirdo in communist Romania reckoning with existential dread. Also finished Susan Taubes's Lament for Julia, a novella paired with various short stories, all with a powerful Freudian bent, Taubes being the daughter of a psychoanalyst and prone to autobiographically inflected fiction. Fathers and daughters are locked in strange relation; men and women antagonize each other; there's much angst around the emergence and forcible repression of sexuality and desire. I also completed a reread of Crime and Punishment (impressive in its structure, if not at the line level; conservative, like much of Dostoevsky, in its premises and sympathies, though not without its points when it comes to the weaknesses that certain modes of thought can have when they're adopted carelessly, as vogues, and in arguing for the necessity of humility against despair when one's despair stems, as Raskolnikov's does, from overweening self-regard). And I read Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet—which was a funny one. Much to love in it, certainly. I also felt a bit of a twang reading, say, Rilke's condemnation of "the unreal half-artistic professions"—among which he includes "almost all of criticism"—"which, while they pretend proximity to some art, in practice belie and assail the existence of all art." Oh look, it's the form to which I've apparently pledged my troth, ha ha whoops.

I admit I wasn't blown away by Solenoid as I thought I might be. It offers a slightly banal resolution to existential crisis... That is, that the narrator ultimately meets the horror he spends about six-hundred pages grappling with—of the possibility that he might be trapped within three dimensions when a fourth, superior dimension might exist, meaning (I know this sentence is Going Places, stay with me) a dimension that is not ruled by the determinism by which any dimension is ruled in the eyes of those who can see it from the next dimension on, the same way that the life of, say, a mite might seem determined to us, all unthinking instinct and bound to a terribly specific and minute purpose, given our position as the mite's vast superior—that he counters the tremendous weight of this fear by turning to an abstract love for humanity and the purpose he finds in raising the child he has with his lover, Irina... It reminded me of the commitment to bourgeois normalcy that the protagonist of Antal Szerb's Journey by Moonlight makes, and how that let me down after his Master-and-Margarita-esque path through other, more hallucinatory forms of experience in the first three-quarters of that novel—which promised, I don't know, something more.

But I can understand the turn. And Solenoid does have some terrific setpieces along the way. One is the protest of the "Picketists"—a sect the narrator stumbles upon that stages demonstrations against life's pain and suffering (their signs bear lines like "Down with Death!" "Down with Rotting!" "Down with Accidents!" "NO to Agony!" and "Stop the Massacre!")—before a building in Bucharest that once housed one of the first institutes of forensic medicine, whose cupola bears thirteen statues depicting the soul's dark sides, Sadness, Despair, Fear, Bitterness, Melancholy, Revulsion, Nausea, Mania, Horror, Grief, Nostalgia, Resignation, and Damnation. Most striking is the way that protest ends, with the statue of Damnation—which has come alive, "as alive and slow-moving as soft glass and black as anthracite"—stamping on the lead protestor, Virgil, crushing him, when he asks her whether anything humanity can offer her will ever be enough.

Cărtărescu is also quite skillful at pacing his plot across the novel's 638 pages, as the narrator discovers each of the six solenoids sprinkled across Bucharest—the massive electromagnets that make possible eerie wonders like levitation and serve as engines that, essentially, power the world—and as he endures his own Virgil-like trial among the Picketists at the novel's end. Translator Sean Cotter also deserves a ton of credit, I'm sure. It can't have been easy to translate a narrative like this one, which depends so much on so many references to Bucharest's geography, Romania's history, and the histories of so many figures, so strangely intertwined—the forensic scientist Mina Minovici, who studied death (through, in Cărtărescu's telling, intense bouts of self-strangulation); the psychologist Nicolae Vaschide, who studied dreams, which in the narrator's mind join death as one of two potential means of escape from this world to the next; and the mathematician Charles Howard Hinton, who married Mary Ellen Boole, daughter of mathematician and logician George Boole, whose other daughter, Ethel, married Wilfrid Voynich, famous owner of the Voynich manuscript, which the narrator ultimately comes to possess and, at the novel's end, offers to the goddess Damnation, whereupon its pages somehow morph into a tesseract, the shape that Hinton once theorized as the fourth-dimensional analogue of the cube; the next level of complexity to it, just as the cube is the next-level of the two-dimensional square—thereby permitting the narrator one glimpse, one moment of contact with whatever it is that lies in the fourth dimension, beyond...

So, you know, it's been a time. If you're in the mood for a long novel about an intelligent, sensitive, neurotic thwarted artist confronting the fear that has oppressed his life, that engages whole histories of mathematics, logic, and philosophical thought along the way, you might give Solenoid a shot. Meanwhile, I'll end this with some words from Rilke in his last letter to the young poet, Franz Krappus, when Krappus was twenty-five: "Do you remember how [your] life yearned out of its childhood for the 'great'? I see that it is now going on beyond the great to long for greater. For this reason it will not cease to be difficult, but for this reason too it will not cease to grow." Arrange your life, he tells Krappus, according to that principle which counsels us that we must always hold to the difficult. I'm certainly not in my twenties as I write this, but the lines still inspire.

#literary#books#mircea cărtărescu#susan taubes#rainer maria rilke#charles howard hinton#voynich manuscript#george boole#franz xaver krappus#sean cotter#nicolae minovici#nicolae vaschide#fyodor dostoevsky#antal szerb

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

He dicho «motor metafísico», pero pienso ahora que podría llamarle también «motor paranoico», en la medida en que toda metafísica es, de hecho, paranoia. De repente, un buen día, ves a tres o cuatro ciegos después de no haber visto ninguno en muchos años, ni siquiera en sueños. Conoces a una mujer llamada Olimpia y al cabo de unos minutos abres un diccionario de pintura por la página de la Olympia, de Manet y, dos horas después, en la calle, descubres la Floristería Olimpia. Son nudos de significado, plexos del sistema neural del mundo que unifica sus órganos y sus acontecimientos, indicios que deberías seguir hasta las últimas consecuencias, y lo harías si no tuvieras los prejuicios estúpidos de la realidad. Deberíamos tener un sentido que discriminara entre el signo y la coincidencia. Ves un día, una detrás de otra, tres mujeres embarazadas: ¿qué quiere decir eso? Y si hubieran sido solo dos, ¿te habría sorprendido también la coincidencia? ¿Y si a las tres añadieras una más, que sale de repente de una casa y camina ante ti por la calle? ¿Y si esta se detuviera, se volviera de golpe y te tendiera una nota arrugada en la que pone tan solo «¡Socorro!», y luego corriera pesadamente calle arriba? ¿Cuánto resiste el hielo de la realidad? ¿Cuándo, en qué momento, sientes su crujido bajo los pies? Atisbas al principio las grietas finas de las coincidencias que se ramifican y se ensanchan de forma alarmante, pero el hielo todavía te sostiene y no te causa problemas por el momento: es tan solo una embarazada más, la cuarta. Puede suceder. No es imposible encontrarse con todas ellas a lo largo de un solo día. Pero la embarazada te entrega una nota, lees el mensaje y de repente el lulo se resquebraja y te hundes en el agua helada, y estás debajo, buscando como una foca un agujero a través del cual poder respirar.

Solenoide - Mircea Cărtărescu

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

La mia illusione era cresciuta tantissimo e continuavo a non decidermi - per certi versi non mi decido nemmeno oggi - a sbottonarmi la camicia, di tanto in tanto almeno, per lasciare che mi cannibalizzasse voluttuosamente.

9 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Porque la realidad te da la historia, no la sustancia. Puedes estar tallado en piedra y no existir; perdido entre unas dunas infinitas, pero si eres un fantasma en un sueño, es precisamente la luz del sueño la que te justifica, la que te construye. Y ahí, en la historia confusa de algún durmiente, eres más verdadero que un billón de mundos habitados.

Mircea Cărtărescu, «Segunda parte» en Cegador, 1. El ala izquierda. Traducción de Marian Ochoa de Eribe.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

(ma il buongusto entrava nella categoria dei valori che dovevano essere denunciati e distrutti)

Solenoide, Mircea Cărtărescu.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Each morning, before opening my eyes, I feel the same anxiety: This again? This is what’s called reality? This is what my life will be: home–school–home–school, with no chance of breaking this vicious and destructive circle? Why was I given, like everyone else like me, a god’s mind, if it had to come with a mite’s body? Why can I think, when I can think of nothing but how I will perish in my hallway, buried in the skin of a creature I will never come to know? Why can I understand everything, if I can do nothing?"

Solenoid, Mircea Cărtărescu

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apostar contra la vida es la única manera de perder, siempre.

#Ruletistul

#BriseidaAlcalá #ComoYEscribo

1 note

·

View note