#kongo religion

Text

Simbi: The Water and Nature Spirit in African Kongo Spirituality and Hoodoo

Simbi, also known as Cymbee or Sim’bi, represents a fascinating aspect of traditional African Kongo spirituality and Hoodoo practices. These mystical beings hold a special place in the beliefs of the Bakongo people and have also influenced spiritual practices in the African American community, particularly in the American South.

Originating within Kongo-speaking communities, the word “simbi” is…

View On WordPress

#African American culture#African Art#African artifact#African religion#Congo Art#kongo religion#Religion History#Simbi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bakongo spiritual protections influenced African American yard decorations. In Central Africa, Bantu-Kongo people decorated their yards and entrances to doorways with baskets and broken shiny items to protect from evil spirits and thieves.

This practice is the origin of the bottle tree in Hoodoo. Throughout the American South in African American neighborhoods, there are some houses that have bottle trees and baskets placed at entrances to doorways for spiritual protection against conjure and evil spirits.

In addition, nkisi culture influenced jar container magic. An African American man in North Carolina buried a jar under the steps with water and string in it for protection. If someone conjured him the string would turn into a snake. The man interviewed called it inkabera

#inkabera#nkisi#hoodoo#african american#african traditional religions#kongo#bantu#central africa#north carolina#bottles#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#glass#dishware#wood#glassware#hearts

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

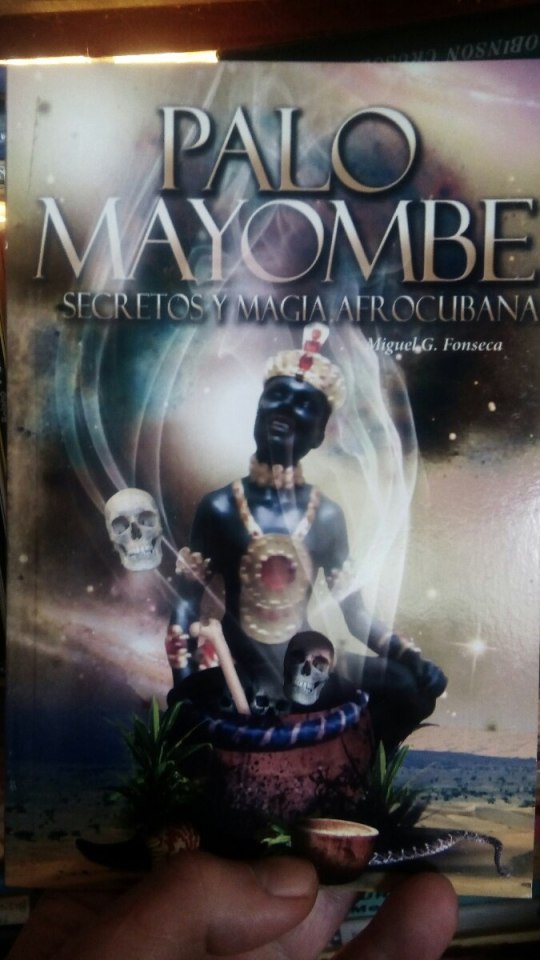

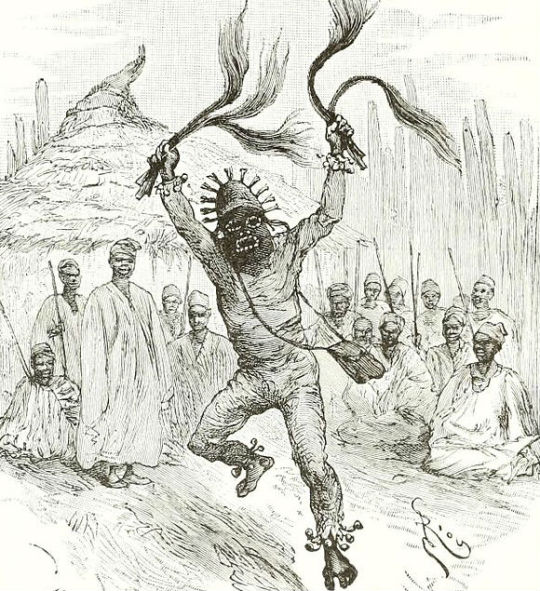

Palo mayombe, is closely related to the origins of the Bantúes tribes as part of a kind of religion that developed in Central Africa, was later taken to the Isle of Cuba, where he joined other religions coming from Africa, specifically Yoruba, taking specific characteristics with regard to the traditions of the island, knows more about this religious current by reading this article.

The Palo mayombe comes from the oldest African beliefs, where “Palo” means tree, and it was considered sacred spirits, because where the souls of the dead lived, this belief reached the northern part of America, especially in all the Antilles, which along with colonialism dispersed towards Central America, however, it is in Cuba, where this religious current took hold and mixed with other African spiritual currents that during that time arrived in Cuba, the Yorubas and the Lucumí. These religions also developed in Brazil and certain regions of the United States. Where they joined with spiritual lines such as Santería and Candombié, creating particular religions such as Shamanism and Voodoo. El Palo, as many call it, has a series of rules called:

Mayombe.

It is a religious cult contained in Palo Monte, where the main belief is based on the natural powers and the veneration of the ancestral spirits that have lived in the African regions. It is a ritual that attempts to establish communication with the dead, through songs, dances and prayers in the “Kikongo” language. For many it is a magic that is responsible for keeping Good (Mbote) and Evil (Mbi) level.

It is characterized by working with the energies of the Nfumbe or dead person and uses two Nganga: one for good and one for harm, it is a traditional and conservative rule. Its practice is carried out entirely in Cuba and has spread to other regions of America, such as the United States, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Panama. However, the large brotherhoods annually receive large numbers of santeros, where they are trained in the ceremonies, rites and activities that allow them to be carried out in different countries.

Brillumba.

Second rule or current within the Palo Monte, which is born from the rules of the previous one. It is very common among the so-called paleros, it comes from the Mayombe rule, where the main characteristic is the use of skulls, in Cuba it was syncretized and Christianized, its foundations are: lightning, zarabanda, mother water, earth. The rite is based on the innovation of the Congo god called Mpumgu, who is the African version of the Yoruba and Lucumi Orishas.

Changany.

It is a current that derives from the Brillumba, original from Cuba, within the Palera spirituality, they cannot deliver Lucero, it is really a sacred house that the Tatas use to perform the Rayas and it is closely related to this current in the ceremonies and spiritual procedures , is a kind of variation that is a little more complex in the rituals and energy processing.

Kimbiza.

The Palo Kimbiza Rule is characterized by linking the forces of nature as animated spirits, to whom it offers shelter to all the souls that inhabit the earth. Its ceremony is performed near a cedar tree called Ngangas, where it becomes a recipient. of the soul of a deceased person, who has previously established to reach Ngangas when he was alive. The Kimbiza order of Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje, created by Tata Andrés Facundo Cristo de los Dolores Petit, is the first completely Cuban religion. The priests of Palo Mayombe are called “Palero” or “Tata”, which represents the father, and “Palera” “Yaya”, mother if she is a woman. Each one must have great knowledge about magic and divination, but to aspire to be a Palero, the person must first pass a test, and check if they are accepted by the spirits, then perform the “Rayamiento”, which consists of a initiation ceremony, where the person assumes full responsibility for all spiritual assignments.

El Palo becomes a Nguey (newly initiated priest), which represents an Iyago in Santeria. Subsequently, it must be initiated by a godfather or godmother in a ceremony similar to that in Santeria, it is secret and the rules are somewhat strict for the initiates, homosexuality is not allowed and when this inclination is discovered it is rejected throughout the Palo Mayombe community.

The house of a palero is called munanso or house, it can only be opened by the palero or palera himself. Each Palera tradition is carried out orally, its priests are in charge of transmitting the traditions to the initiated in this way, the idea is to preserve the secrets of the Palo Mayombe through the fidelity of the person, the secrets of this religious current They are not easily available in books or texts, they are in the mind and knowledge of each Palero. (See article Olodumare)

History.

The history of Palo mayombe dates back to the region of Cameroon, before the migration of the Bantu to the south and settling in Angola, Congo and Cabinda. From there came a large number of slaves who with them also came the Palo Monte belief, the ceremonies and songs used by the slaves reached the Island of Cuba and began to be combined with the Spanish language, the same influence fell on other regions. from Central America and the Caribbean. Towards the 20th century, Palo mayombe began to proliferate and spread in Cuban communities settled in countries such as Venezuela, the United States, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where in some countries the tradition remains intact, just as it develops in Africa.

Currently the Palo Mayombe culture is very large, especially in the Cuban regions of Santiago, Matanzas and Pinar del Rio, most of the practitioners are black, who in turn are followers of Catholicism. (See article African rites).

Vista como religión

Palo mayombe, also known as Palo, is considered a religion that mixes the shamanic current and elements of spiritualism, black magic and Catholicism, the main root arises from the Congo region that later expanded to other regions of the African continent and with the arrival of slaves to America, it spread throughout almost all of Latin America.

On this continent, the Palera religion began to take its first steps in regions where African tribes were beginning to establish themselves, these tribes were Mondongo, Bisongo, Timbiseros and Mandingas, who maintained their tradition of Bantu culture, in this way it took shape until that the three most important currents were born and then dispersed throughout the island.

Its strength consists of possessing and using the spiritual criteria of other religions, the mixture of African and European spiritual concepts allowed it to become a strong spiritual current, each one (Mayombe, Criyumba and Kimbiza) establishes a series of criteria that each palero must comply to the letter, however there are communal elements among them that allow the implementation of the Palo Mayombe criteria.

THERE ARE MORE THAN 50 Remaining Pages of this very important Historical document on Palo Mayombe - so if you click the title you can read the entire piece. Use Google Translate to make it your language in one click.

0 notes

Text

More on Hoodoo (spirituality)

In my previous post I talked about traditional hoodoo where it started I want to talk a little more on it.

When we look at the origins of the word Hoodoo which actually comes from the real term "Hudu", meaning "spirit work," coming from the Ewe language spoken in the West African countries. Hudu is a African dialect spoken in the Ewe language of the Ewe people in West Africa.

Hoodoo has Bakongo magical influence from the Bakongo religion incorporating the Kongo cosmogram, Simbi water spirits, Yoruba people incorporating iron work from their deity which is used in hoodoo like railroad spike or horseshoe and Nkisi and Minkisi practices.

Sweetening Jars:

Traditional Sweeting Jar

Sweetening jars are a tradition in Hoodoo to sweeten a person or a situation in a person's favor. The practice is appropriated and its meaning is misunderstood outside the African-American community. Traditionally sugar water is used.. not honey.

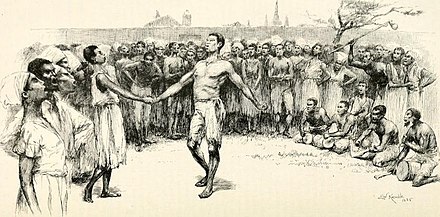

During the slave trade, the majority of Central Africans imported to New Orleans, Louisiana were Bakongo (Bantu people). This image I like and wanted to show it if anyone hasn't seen it. It was painted in 1886 and shows African Americans in New Orleans performing dances from Africa in Congo Square. Congo Square was where African Americans practiced Voodoo and Hoodoo. ("So again when any non traditional Root Worker says there isn't a little voodoo with hoodoo there wrong")

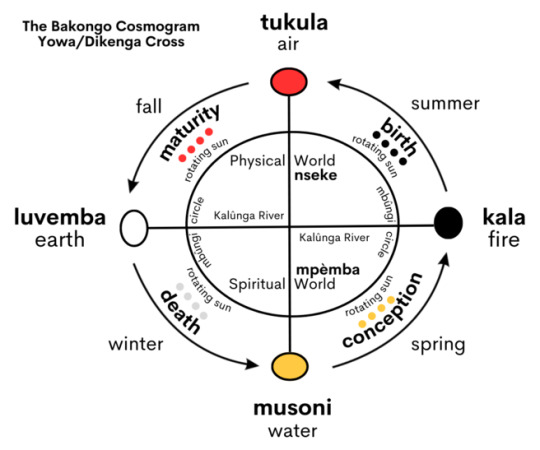

Next we have this diagram the Kongo Cosmogram Cross.

Kongo Cosmogram aka Crossroads.

The Kongo cosmogram aka The Crossroads is from Bakongo origins in Hoodoo practice and is very important. In Kongolese spiritual beliefs and practices are present in Hoodoo such as the Kongo cosmogram.

Why is it important? The basic form of this symbol is a simple cross (+) which (symbolizes the rising of the sun in the east, the setting of the sun in the west, and represents cosmic energies.)

However, is not the same as your typical Christian cross.

The vertical line of the cosmogram is the path of spiritual power from God at the top traveling to the realm of the dead below where the ancestors reside.

The horizontal line in the cross represents the boundary between the physical world which is the (realm of the living) and the spiritual world (realm of the ancestors).

The horizonal line is a watery divide that separates the two worlds from the physical and spiritual, and thus the "element" of water plays a role in African American spirituality just like Voodoo.

The Kongo cosmogram cross symbol has a physical form in Hoodoo called the crossroads where Hoodoo rituals are performed to communicate with spirits.

Dancing: Counterclockwise sacred circle, dances in Hoodoo are performed to communicate with ancestral spirits using the sign of the Yowa cross.

The Ring shout is not part of traditional Hoodoo as far as the actual rituals are concerned, but it is part of church that has its origins from the Kongo region also the ring shouters dance in a counterclockwise direction. The ring shout follows the cyclical nature of life that we see in the diagram. It represents Kongo cosmogram of birth, life, death, and rebirth.

Through counterclockwise circle dancing, ring shouters built up spiritual energy that resulted in the communication with ancestral spirits, and led to spirit possession by the Holy Spirit or ancestral spirits. The spiritual vortex in the center of the ring shout is a sacred spiritual realm. The center of the ring shout is where the ancestors and the Holy Spirit reside at. The ring shout tradition continues in Georgia. Inside reflective materials and the used of reflective materials to transport the recently deceased to the spiritual realm. Broken glass on tombs reflects the other world. It is believed reflective materials are portals to the spirit world.

#Hoodoo Lesson#spiritual#like and/or reblog!#traditional hoodoo#rootwork#google search#southern hoodoo#Hoodoo history#Real hoodoo#ask me anything#Hoodoo initiation#Ring shot#follow my blog#ask me questions#message me

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

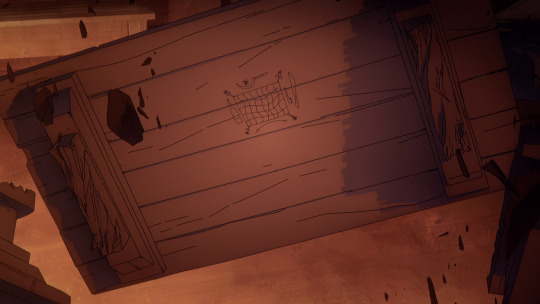

Vodou symbolism in Castlevania Nocturne

Vodou developed among Afro-Haitian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. Its structure arose from the blending of the traditional religions of those enslaved West and Central Africans, among them Yoruba, Fon, and Kongo, who had been brought to the island of Hispaniola. There, it absorbed influences from the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue, most notably Roman Catholicism but also Freemasonry. Many Vodouists were involved in the Haitian Revolution of 1791 to 1801 which overthrew the French colonial government, abolished slavery, and transformed Saint-Domingue into the republic of Haiti.

At the heart of Vodou are the symbols known as vèvè. These cosmograms are intricate drawings made with cornmeal, coffee, or flour, and they serve as the visual representation of the spirits and deities (known as lwa, also called loa or loi) honored in Vodou. Each vèvè corresponds to a specific spirit, and invoking them involves drawing the corresponding symbol on the ground. This is often performed by an initiate who has learned the technique and is an essential part of Vodou rituals and ceremonies.

Let's look at some of the symbolism shown in Nocturne.

1. Agwe Arroyo or Agwe Tawoyo/Agwe 'Woyo - "Agwe of the Streams"

Captain of Immamou, the ship that carries the dead to the afterlife. He cries salt-water tears for the departed. He assisted the souls of those that suffered crimes against humanity during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Agwe is called to calm the waves of the sea or ensure happy sailing, but mainly he is worshipped by those who fish and whose life depends on the life in the waters. People under his protection will never drown and water will never harm them.

2. Kouzen Zaka, or Azaka

The patron lwa of farmers, but he is also known as a lwa travay, a work lwa. Kouzen Zaka, represented by this vèvè, is the guardian of the fields in Haitian Vodou. The drawing of his symbol showcases elements of agricultural activity, including the earth, machete, sickle, hoe. Zaka is closely tied to work and is revered by farmers and those who rely on agriculture for their livelihood.

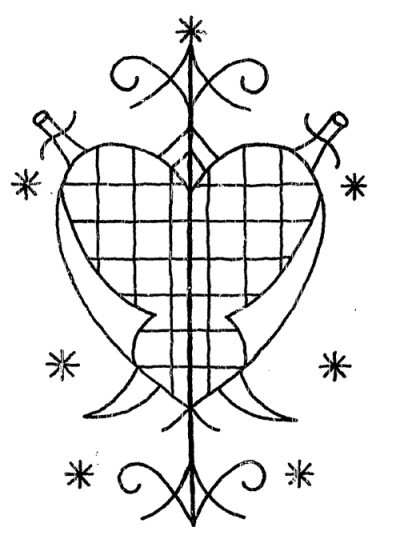

3. Erzulie Dantò or Ezilí Dantor

The main lwa of the Petwo lwa family in Haitian Vodou. She is a powerful and protective mother figure, often depicted holding a knife, symbolizes justice and will forcefully fight to protect her children, who are her loyal followers. She is a single mother, a Haitian peasant who is fiercely independent and takes care of her own, a strong protector of women and children.

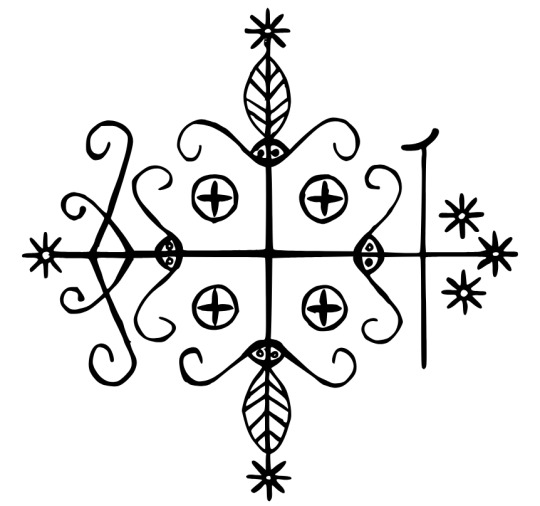

4. Legba: The Guardian of the Gates

Papa Legba, the first spirit to manifest during a Vodou ceremony, holds a special place in the Vodou Pantheon in Haiti. His vèvè symbolizes his role as the barrier between the two worlds, with two perpendicular axes and his cane. Known as a trickster Loa, he usually appears as an old man on a crutch or with a cane, wearing a broad-brimmed straw hat and smoking a pipe, or drinking dark rum. The dog is sacred to him. He carries a sack on a strap across one shoulder from which he dispenses destiny. He is believed to speak all human languages. In Haiti, he is the great elocutioner: Legba facilitates communication, speech, and understanding. During Vodou ceremonies he opens the spiritual gateway that separates the Loas from our physical world.

In addition, Papa Legba is the guardian of portals, doors, and crossroads. His role is critical in any Vodou ritual, as he's the one who grants access to the other Loas and allows them to manifest themselves during the ceremony.

What we hear Annette chant in the series is 'Papa Legba: Ouvè Baryè'a' (Papa Legba: Open the Gate).

There's a lot more to dive into, but this was a summary.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voodoo and Hoodoo: What’s the Difference?

If you live in America, you have undoubtedly come across the terms of voodoo and hoodoo. What is the difference between the two, and how does African (umbrella term) culture play a role in each?

Voodoo

(A.K.A. Vodou, Voudou, Vodun) Voodoo is a religion that originated within Africa amidst the Atlantic slave trade. Its structure comes from a mix of traditional religions of West and Central enslaved Africans (Yoruba, Kongo, and Fon). Once brought to the Hispaniola island, Voodoo saw influences of the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue (Freemasonry).

Many Haitians who practice Voodoo also practice Roman Catholicism, not seeing a contradiction between the two systems existing simultaneously. Characterized as Haiti’s “national religion”, Voodoo is one of the most misunderstood religions in the world. Voodoo is monotheistic, giving the teachings of a single supreme God. Believed to have created the universe, this entity is called Bondye or Bonié. For Vodouists, Bondye is seen as the ultimate source of power. This perception of God is also seen as remote, not involving itself in human affairs. While Vodouists often equate Bondye with the Christian God, Vodou does not incorporate belief in a powerful antagonist that opposes the supreme being akin to the Christian notion of Satan.

Vodou also holds the belief of many beings known as Iwa, a term that varies in its translation from “spirits” to “gods”. These beings can in many ways be equated to Christian angels in many of its cosmology. The lwa can offer help, protection, and counsel to humans, in return for ritual service. Each lwa has its own personality and individual correspondences. They can be either loyal or capricious in their dealings with their devotees, with many believing that the lwa are easily offended. When angered, the lwa are believed to remove their protection from their devotees, or to inflict harm.

Vodou also teaches a perspective of the human soul, which is believed to be divided into two parts (both of which exist within the head of a person). One of these is the ti bonnanj ("little good angel"), and it is understood as the conscience that allows an individual to engage in self-reflection and self-criticism. The other part is the gwo bonnanj ("big good angel") and this constitutes the psyche, source of memory, intelligence, and personhood. Vodouists believe that every individual is intrinsically connected to a specific lwa. This lwa is their mèt tèt (master of the head). They believe that this lwa influences the individual's personality. At bodily death, the gwo bonnanj join the Ginen, or ancestral spirits, while the ti bonnanj proceeds to the afterlife to face judgement before Bondye.

Vodou does not promote a dualistic belief in a division between good and evil. It offers no prescriptive code of ethics. Rather than being rule-based, Vodou morality is deemed contextual to the situation.

It is very important to respect Vodou as the closed practice that it is. While misunderstood through various contextualizations, it is a religion felt deeply by a group of people who use it to guide their lives. Those outside do not have the right to infringe upon said spaces.

Hoodoo

It is important to understand that Hoodoo does not describe a religion. Rather, Hoodoo is a set of mystical beliefs hailing from along the Mississippi River with influences from Indigenous herbalism, African spiritualities, and Christian influences. Practitioners of Hoodoo are called rootworkers, conjure doctors, conjure man or conjure woman, root doctors, Hoodoo doctors, and swampers.

Many Hoodoo traditions specifically draw from the beliefs of the Bakongo people of Central Africa during the Atlantic slave trade. After their contact with European slave traders and missionaries, some Africans converted to Christianity willingly, while other enslaved Africans were forced to become Christian which resulted in a syncretization of African spiritual practices and beliefs with the Christian faith. Enslaved and free Africans learned regional indigenous botanical knowledge after they arrived to the United States, including another influence to what would become known as Hoodoo.

During the transatlantic slave trade a variety of African plants were brought from Africa to the United States for cultivation (okra, sorghum, yam, benneseed, watermelon, black-eyed peas, etc.). African Americans had their own herbal knowledge that was brought from West and Central Africa to the United States. When it came to the medicinal use of herbs, African Americans learned some medicinal knowledge of herbs from Indigenous peoples. However, the spiritual use of herbs and the practice of Hoodoo remained African in origin as enslaved African-Americans incorporated African religious rituals in the preparation of North American herbs and roots.

Hoodoo was also a key part in black revolution in the United States. Enslaved women would use their knowledge of herbs to induce miscarriages so white owners wouldn’t be able to take their children. There were also examples of hoodoo being used to poison and kill white slave owners. The Bible itself, in conjunction with Hoodoo, was used in slave liberation. Free and enslaved people could read the stories of the Hebrews in the Bible, and found them similar to their situation in the United States as slaves. The Hebrews in the Old Testament were freed from slavery in Egypt under the leadership of Moses (held to be a conjurer in the beliefs of many who practice Hoodoo).

Hoodoo is also a closed practice, requiring initiation for practitioners.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

!! ️SCHOOL WILL NEVER TEACH YOU THIS👇🏿

|| THE AFRICAN ORIGIN OF THE NAME ISRAEL ||

The teachings of Bundu Dia Kongo.

Ne MUANDA NSEMI teaches the Makesa mu Nzila Kongo: the mystery of the name, because the name is the carrier of evil and beneficial influences to the one who bears it.

The name is also linked to a person's state of being.

Como example: with Zulu Makeba, with MBEMBA ZULU, with NKEMBO WA MONESUA, with NSANSUKULU A KANDA, YAYA VITA KIMPA, MFUMU KIMBANGU, with MUANDA NSEMI, NAVITA NGOLO, MFUKA FUAKAKA MUZEMBA etc.

Ne MUANDA NSEMI also teaches Makesa mu Nzila Kongo that speaking French, English is not synonymous with being intellectual.

Africans have become, complexly, foreign languages fanatics. Africans believe that giving a French, English or Hebrew name would have more meaning than in their mother tongue.

Example:

-that one called PEDRO thinks it's better to be called a stone than to be called TADI in his mother tongue which is KIKONGO.

- whoever is called ELOHIM believes this designation is divine in origin, but refuses to be called ELIMA in their language, while ELOHIM= ELIMA in Kikongo.

.

Ne MUANDA NSEMI teaches the Makesa mu Nzila Kongo that the word KELIMA means a Messenger God, a Genius, an Angel. When the letter 'K' falls, KELIMA becomes ELIMA, in the plural BIKELIMA: the flashing, the SEZIMA, the SELIMA.

.

Elima word expansion, adding letters. Oh give the words Elohima Elohim in Hebrews

Eli, El, stands for ELIMA, Kelima.

Give names like: EL Fatah, EL Chadai, ELION.

The abbreviation " EL " is also in the name of God, Archangels, Prophets in the Hebrew language as: Deus Yave Israel. Archangel Michael, Michël, Raphael, and other names such as: Ishmael, Samuël, Daniël, Emmanuel, Ezequiël...

.

Kelima, Elima is synonymous with God of Simbi, Nomo, a messenger God, a Genius of Nature, an Angel, a Radiant of Light.

No more no less On the cross Jesus shouted Elima (=Eli), Elima (=Éli), why have you forsaken me?

.

A Kelima, an Elima is a Great Mulimu, a Great Spirit of Nature: Each Elima has its own name:

And HOGU BATALA, OUR KAMBISI, KOLOKOSO, OUR KINZOLA, OLONGO, OUR MANDOMBE KALI, LUEZI (LUEJI, LUEJ, RUEJ) , RA, ISISI, MANATA LUDI etc.. These are some famous Elima from Egyptian BUKONGO.

.

Isis stands for Isisi: a goddess (an Elima) of Ancient Egypt.

.

Ra is a male Elima (+), isisi a female (-).

IS, RA, EL giving Israel. It is the fusion of positive (Ra) and negative (isisi), the union of man and woman gives an androgynous Elima (EL), both male and female. An equal Elima is called Mahungu, Malunga, Ilunga, Complete Being, made in the image of the Great God KONGO KALUNGA.

.

The holy book of Kongo (MAKONGO) religion teaches that Kana was the land of High Priest MELCHISEDEK.

Mukana verb means Nkua Vema, an enthusiastic, a passionate, a jealous, a fanatic.

Kikana is fanaticism: Bakana ba Nzambi are fanatic of God, KANA, KANANA country.

Originally Kana and Madian were inhabited by blacks

Midian was inhabited by the High Priest, Gestro (Yetelo), this High Priest of Bukongo teaches Moses to contact the Angel of the people of Israel who is the God of Israel.

Kana was inhabited by High Priest Melchisedek, this High Priest of Bukongo teaching Hibrahim, Abraham to enter into communion with God of Israel.

.

In kikongo language the sun is called Ntangu lowa the Great Nabi Kongo say the heart of the sun is called KISEDEKI.

-so MAMBU MELE KISEDEKI i mean problems went to the heart of the sun. The word MELE is a Kikongo verb form from the verb KUENDA which means to go.

.

In Bukongo, a Great Nabi Kongo that serves as a transmission channel between the Assemblies of God (Temple) and the Heart of the Sun, bears the grand opening title of Ne MELE KISEDEKI.

.

The bible says Melchisedik king of Salem brought bread and wine. He was a sacrifice of a very high God. He bless Abraham by the most high God

Ibrahim (Abraham) gave Dime to Mechisedek (Genesis 14: 18-20)

So here is Abraham, the first prophet of God of Israel) who is blessed by a High Priest black a Great Nabi Kongo, Ne MELE KISEKEDI.

Abraham father of the faith of the white Hebrews pay Dime to the Priest of the Most High God Ne MELE KISEDEKI King and Priest of KANA we will distort in Kanan Canaan because of their variants Kanana.

- Thus Abraham (Ibrahim) imitating copying the language of the people of Kana (THE BAKONGO) and distorting the graft in the Hebrew language, these words distort the source in Kikongo

- in Kikongo language

Excerpt from the book The Mysteries of KIKONGO

Written by NE MUANDA NSEMI Nlongi' to KONGO.

Kinshasa on 22-11-1995

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you make of Tom Berendt's strange claims of Bosou Twa Kon apparently having "Celtic origins?" He already makes the (tiresome) assertion of Maman Brijit being St. Bridget (without providing a source of course!) and went on various weird claims of Breton pirates being connected to Ireland and possibly having reached Haiti followed by the whole "bull archetypes around the world", though I was curious what your thoughts might be on his argument seeing as this managed to get into the Journal of Haitian studies...

I hadn't read this paper before, but I found it and took a look and boy, it is a LOT. To me, it boils down to this:

If Darth Vader has been appropriated into Haitian Vodou, then the possibility remains open that a Celtic three-horned bull deity might well have been appropriated too, though many years earlier. (Berendt, pg5)

Darth Vader has not been appropriated into Vodou. His mention of a practitioner placing a figuring of Darth Vader with a Baron is an example of cultural transference and ingenuity, and his inability to recognize that AND use it as a way to suppose that there is a deep and abiding Celtic influence in an African-descended religion is honestly indicative of a poor grasp of cultural relativity, the politics and power of occupation, and generally the entirety of Haitian Vodou.

He presents no definitive ties, only supposition, and uses cultural likeness as definitive proof of Celtic influence when cultural likeness is a worldwide phenomenon. He mentions in passing the actual origin of Bossou as a royal figure in Dahomey, but can't give that actuality the respect or importance it is due. What does it mean that the elevated spirit of a king in a nation that was occupied, kidnapped, and dragged across an ocean to live in a new place still exists? What does it mean that this spirit manifests as an unconquerable bull? He glosses over that and what that means in the context of what Haitian Vodou is, which is a system on liberation that literally changed the course of modern politics.

Instead, he wants to say that it is really European, and what does that mean and what does that say about scholarly impressions of Vodou and Haitian culture in general? How he comes across with his ideas about origins is as kind of a gotcha without having a good grasp of history and culture. He also alludes to the idea that Lasiren is more related to European conceptions of mermaids than her actual Kongo roots and that's kind of astounding. This idea that core parts of Vodou need to have European roots because of colonial occupation underlines a need to insert White influence where it doesn't need to be.

His documentation of potential Breton presence is not definitive and was not present during the crucible period of formation of what we know as Haitian Vodou...and it needs to be underlined as potential. The clearest Breton presence was on Tortuga, an island off the coast of Haiti that was used as a pirate port but that was even contested Breton territory in that it changed colonial hands repeatedly. I have not read the book he mentioned about Brenton presence on the island, but I'm curious about tracking down a copy.

My overall question about this kind of scholarly writing is why? What does this actually do beyond to try to continue to exert a kind of power over the narrative of what Vodou is and isn't? What does this kind of writing actually seek to do?

It's also important to look at what the author does otherwise. He does not have a background in Vodou, nor does he have any body of work that would support that he has been a student of a community that has shared history and experience with him. He does not writer on Vodou in general, and while he is very interested in religious depictions of bovine veneration, he doesn't show that he has the history or community credential to hold this up.

It's disappointing. In the last few years, I have really come to the position that those outside of Vodou are not who should be writing about Vodou. That's not to say practitioners will always produce quality writing, but it would undercut scholars trying to make huge leaps of evidence and logic that don't actually exist in the real world.

For more reading about the origins of Bossou, A Transatlantic History of Haitian Vodou by Benjamin Hebblethwaite has some nice chewy stuff in it. It's a very think-y book that I haven't finished yet, but it's good.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

WEST AFRICAN RESOURCES

The Anthropological Masterlist is HERE.

West African is an African region that spans the western part of the continent.

AGNIS ─ “The Agnis, or Anyi, people are an African people. They are native to the Ivory Coast.”

─ Anyi Information

AKAN ─ “The Akan people are an African people. They are native to Ghana and the Ivory Coast.”

─ Pre-Colonial History of Ghana

─ Modern-Day Akan

─ Akan Dictionary

ANNANG ─ “The Annang, or Anaang, people are an African people. They are native to southern Nigeria.”

─ Annang Dictionary

ASHANTI ─ “The Ashanti, or Asante, people are an African people. They are native to the Ashanti region in Ghana.”

─ Ashanti Information

─ Ashanti Culture

─ Ashanti History

BAMBARA ─ “The Bambara people are an African people. They are native to West Africa.”

─ Bambara Art

─ Bambara Language (in French)

BASSARI ─ “The Bassari people are an African people. They are native to the Kédougou region of Senegal.”

─ Bassari Language (in French)

EWE ─ “The Ewe people are an African people. They are native to the coastal areas of West Africa.”

─ Ewe Information

─ The Anlo-Ewe People

─ The Adze in Ewe Mythology

FON ─ “The Fon, or Dahomey, people are an African people. They are native to south Benin and southwest Togo and Nigeria.”

─ The Dahomey Amazons

IBIBIO ─ “The Ibibio people are an African people. They are native to the coasts of southern Nigeria.”

─ Ibibio Language Resources

─ Ibibio Masks

IGBO ─ "The Igbo, or Ibo, people are an African people. They are native to Nigeria.”

─ Igbo Culture

─ Igbo Dictionary

ISOKO ─ “The Isoko people are an African people. They are native to the Isoko region in Nigeria.”

─ Isoko Information

─ Isoko Culture and History

─ Isoko Dictionary

KONGO ─ “The Kongo people are an African people. They are native to the Atlantic coast of central Africa.”

─ Kongo Language Resources

─ Kongo Dictionary

KONO ─ “The Kono people are an African people. They are native to the Kono District in eastern Sierra Leone.”

─ Kono Culture and Rituals

NIGERIAN ─ “The Nigerian people are an African people that share the Nigerian culture. They are native to Nigeria.”

─ Nigerian Information

─ Colonial Nigeria

SERER ─ “The Serer, or Seereer, people are an African people. They are native to Senegal.”

─ Serer Information

─ Serer Language

TALLENSI ─ “The Tallensi, or Talensi, people are an African people. They are native to northern Ghana.”

─ Tallensi Culture

─ Tallensi Development and Culture

URHOBO ─ “The Urhobo people are an African people. They are native to the Niger Delta in Nigeria.”

─ Ughelli Kingdom Information

─ Urhobo Dictionary

VODUN ─ “Vodun, or Vodon, is a West African religion. It originates in West Africa.”

─ Christians and Vodun

YORUBA ─ “Yoruba, or Isese, is a West African religion. It originates in southwestern Nigeria.”

─ The Yoruba People

─ Yoruba Culture (in Spanish)

─ Yoruba Mythology

#resources#agnis#akan#annang#ashanti#bambara#bassari#ewe#fon#ibibio#igbo#isoko#kongo#kono#nigerian#serer#tallensi#vodun#yoruba#west african

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

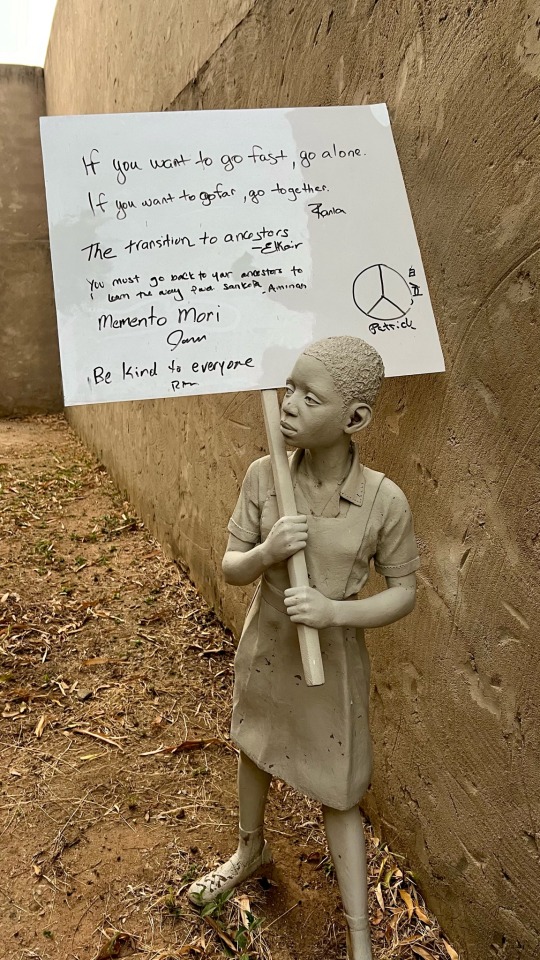

I took a captivating trip to the Nkyinkyim museum in Ada, just a 2-hour drive from Accra. The tour, priced at 100gh per person, was hosted by a griot, a very enthusiastic storyteller whose energy transformed the tour into an exciting journey.

The tour commenced with artifacts at the entrance, revealing the wonders of Sudano-Sahelian architecture dating back to 2500BC. The structures, crafted from organic materials like red mud, clay, and bamboo, showcased the remarkable skill and eco-friendly ingenuity of our ancestors. The community engagement in the construction process mirrored their deep connection with nature.

Intrigued by the symbolism etched on the walls, I marveled at the adinkra symbols, patterns, and shapes that were not only aesthetically pleasing, but held profound meanings. The journey unraveled the cultural ties across Africa, even discovering that Sudan boasts more ancient pyramids than Egypt.

The griot animatedly shared the wisdom behind the symbols—footprints symbolizing our shared humanity, the spider embodying intelligence, the tortoise exemplifying adaptability, and the snail conveying the concept of leaving a lasting legacy. The ant emerged as a powerful symbol of collaboration and community, echoed by the Nkyinkyim symbol representing resilience inspired by nature.

There was also a structure that was described as a life sized Lukasa memory board which challenged the notion that African traditions were solely oral. It became clear that our history was archived through symbols, writings, and memory boards, providing a unique form of communication despite the challenges faced during colonial times.

The journey progressed to a wall adorned with discs inspired by the Dikenga cross, a core symbol of Bakongo religion of the Kongo people symbolizing the cardinal points of human existence and the cycle of life.

The emotional apex was the veneration site—a symbolic memorial to enslaved ancestors. Sculptures conveyed tales of capture, from shock and determination to hidden identities and interrupted hair appointments. The vivid facial expressions on the sculptures offered a poignant glimpse into their harrowing experiences and the traumatizing ways through which they were captured.

There was a wall featuring diverse writings from across the continent, such as Nsibidi and vèvè, underscoring the richness of African history. The trip left me inspired to delve deeper into our heritage, resonating with the concept of Sankofa: going back to our ancestors' ways to chart a purposeful future.

The final chapter featured paintings showcasing accomplished individuals of African descent, a testament to resilience and exceptional lives emerging from the shadows of history. This transformative experience reinforced the belief that understanding our roots definitely shapes the trajectory of our future endeavors.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

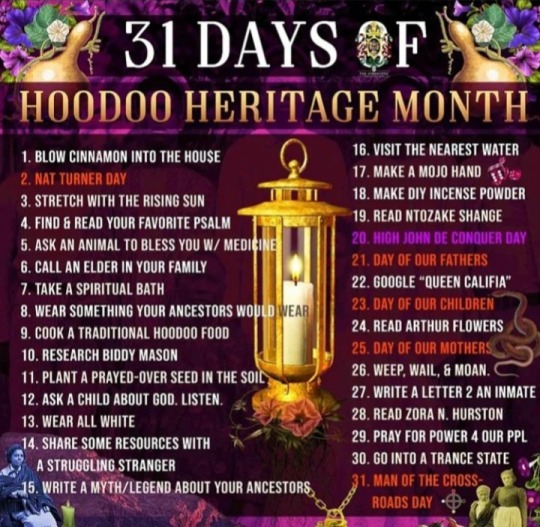

Happy Hoodoo Heritage Month fam 🖤

Giving 💐💐 & many thanks to the OG herself @MamaRuehh for blessing the Culture this month long celebration of so things Hoodoo. Wishing all my juju babies, workers, elders, a victorious & fruitful season ✊🏾

Hoodoo (as we presently call it today) is an ATR (African Traditional Religion) that is endemic to the American South. Borne out of the need for survival & solace, it is a melting pot of various African Traditional Religions that our - more recent - enslaved Central & West African ancestors brought to this land during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Upon their arrival to this land, to survive & connect with one another, they exchanged these traditional religious & cultural treasures of ancient ancestral knowledge and wisdom. And so, Hoodoo was born.

Thus, Hoodoo is the birthright of all Black American descendants of the West & Central African Peoples enslaved in the United States. Whether you choose to claim that birthright, is up to you.

Hoodoo is our Religion, Tradition, Culture, & way of life - deeply rooted in the Cosmology of Kongo Traditions/Religions.

Hoodoo is Black Culture. Hoodoo is the Black Church. Hoodoo is the Black Household. Hoodoo IS Soul Food. It's the way we cook, the way we dance, the way we sing, the way we venerate our Ancestors & elevate our Dead, the way we fight, the way we love, the way we protect ourselves, the way we thrive and survive in this world, etc. generation after generation. Everything we are is Hoodoo.

If ya didn't know, now ya know!

#hoodoo juju#Hoodoo#hoodooreligion#hoodooculture#Rootwork#conjure#juju#hoodooheritagemonth#hoodooheritage

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conjure canes in the United States are decorated with specific objects to conjure specific results and conjure spirits. This practice was brought to the United States during the transatlantic slave trade from Central Africa. Several conjure canes are used today in some African American families. In Central Africa among the Bantu-Kongo, banganga ritual healers use ritual staffs.

These ritual staffs are called conjure canes in Hoodoo which conjure spirits and heal people. The banganga healers in Central Africa became the conjure doctors and herbal healers in African American communities in the United States. The Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida collaborated with other world museums to compare African American conjure canes with ritual staffs from Central Africa and found similarities between the two, and other aspects of African American culture that originated from Bantu-Kongo people.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#central africa#harn museum of art#african american#banganga#kongo#ritual#conjure cane#hoodoo#vodun#voodoo#african traditional religions

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

0 notes

Text

Different Styles Of Voodoo

When I hear that a country or city don't practice real Vaudou aka voodoo it bothers me when that person don't really know what voodoo, Vodou, Vodun etc is. Some think that it started in Haiti or that it isn't real if your not initiated in Haiti. So I wanted to make this quick post to show a few of the different styles of voodoo there are. Do the proper research and choose which practice calls to you.

First up is African Vodun is an is the birth place of vodun a ancient religion practiced by some 30 million people in the West African nations of Benin, Togo and Ghana. With its countless deities, animal sacrifice and spirit possession, voodoo — as it's known to the rest of the world — is one of the most misunderstood religions on the globe.

Second Haitian Vodou is an African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti. It arose through a process of syncretism between several traditional religions of West and Central Africa and Roman Catholicism. Vodou revolves around spirits known as lwa. Typically deriving their names and attributes from traditional West and Central African divinities, they are equated with Roman Catholic saints and the central ritual involves practitioners drumming, singing, and dancing to encourage a lwa to possess one of their members and thus communicate with them.

Third. Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo, is an African diasporic religion which originated in Louisiana, now in the southern United States. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional religions of West Africa, Haitian Vodou and some christianity.

Forth Santería, also known as Regla de Ocha, Regla Lucumí, or Lucumí, is an African diasporic religion that developed in Cuba during the late 19th century. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional Yoruba religion of West Africa, the Catholic form of Christianity, and Spiritism. This is the same as the Ifa in Africa except they use saints also

Fifth Palo: also known as Las Reglas de Congo, is an African diasporic religion that developed in Cuba. This is the first practice that hit first before Santeria. It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional Kongo religion of Central Africa, the Roman Catholic branch of Christianity, and Spiritism.

Sixth Espiritismo: Spiritism. Espiritismo (Spiritism) is rooted in the belief system that the spirit world can intervene in the human world and is widely practiced in Puerto Rico it not voodoo but I wanted to add it. At its most basic level, it invokes God and The Positive Spirits to divine for and assist the person. There is the use of a table covered with a white cloth, a large bowl full of water, and a crucifix. There are no initiations into this tradition and people work together at gatherings called Misas.

Seventh Sanse: Sanse is a cross between Spiritism and the 21 Divisions. In this tradition, the dead and the Lwa (or Misterios) are worked with spiritually. There is an initiation called a Bautizo (Baptism) and people work withall sorts of different spiritual tableaus, or frameworks.

Eight. Obeah, or Obayi, is a series of African diasporic spell-casting and healing traditions found in the former British colonies of the Caribbean. These traditions derive much from traditional West African practices that have undergone cultural creolization.

Ninth. Dominican Vudú, known as Las 21 Divisiones (The 21 Divisions), is a heavily Catholicized syncretic shamanistic religion of African-Caribbean origin which developed in the erstwhile Spanish colony of Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola. Now 21 Divisiones/Dominican vudu is very similar to the tchatcha/kwakwa/Deka lineage in Haiti. In 21 Divisiones and in the tchatcha lineage of Haitian vodou, is the north part of Hati and the initiations are different and the temples are organized differently.

Tenth. Trinidad Orisha, also known as Shango, is a syncretic religion in Trinidad and Tobago and the Caribbean, originally from West Africa.

I these are some of the voodoo style practices around the world .

#Types of voodoo#African practices#Voodoo#Vodou#Vodun#Spiritual#Voodoo Styles#Different voodoo#Voodoo styles#follow my blog#ask me anything#ask me stuff#like or reblog#like and comment#Spiritual information

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louisiana Voodoo - Wikipedia

Louisiana Voodoo (French: Vaudou louisianais, Spanish: Vudú de Luisiana), also known as New Orleans Voodoo,

is an African diasporic religion that originated in Louisiana, now in the southern United States.

It arose through a process of syncretism between the traditional religions of West Africa, the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, and Haitian Vodou.

No central authority is in control of Louisiana Voodoo, which is organized through autonomous groups.

BELIEFS-

Louisiana Voodoo has no formal theology,[20] although it displays its own spiritual hierarchy.[16] Writing in the 2010s, the Voodoo practitioner and poet Brenda Marie Osbey described a belief in "a somewhat distant but single deity" being part of the religion,[26] while Rory O'Neill Schmitt and Rosary Hartel O'Neill expressed the belief that contemporary Voodoo was monotheistic.[27]

Many practitioners of Voodoo have not seen their religion as being in intrinsic conflict with the Roman Catholicism that was dominant along the Mississippi River.[12]

Louisiana Voodoo also displayed a range of lesser deities, the names of which were recorded in various 19th-century sources.[28]

One of the chief deities was Blanc Dani, also known as Monsieur Danny, Voodoo Magnian, and Grandfather Rattlesnake. He was depicted as a serpent and associated with discord and the defeat of enemies.

[28] Another recorded name, Dambarra Soutons, may be an additional name for Blanc Dani.[28] It is also possible that Blanc Dani was ultimately equated with another deity, known as the Grand Zombi, whose name meant "Great God" or "Great Spirit;"[28] the term Zombi derives from the Kongo Bantu term nzambi (god).

Another prominent deity was Papa Lébat, also called Liba, LaBas, or Laba Limba, and he was seen as a trickster as well as a doorkeeper.

[28] he is the only one of these New Orleans deities with an unequivocally Yoruba origin.[30]

Monsieur Assonquer, also known as Onzancaire and On Sa Tier, was associated with good fortune, while Monsieur Agoussou or Vert Agoussou was associated with love.[28]

Vériquité was a spirit associated with the causing of illness, while Monsieur d'Embarass was linked to death.

Charlo was a child deity. The names of several other deities are recorded, but with little known about their associations, including Jean Macouloumba, who was also known as Colomba; Maman You; and Yon Sue.[28] There was also a deity called Samunga, called upon by practitioners in Missouri when they were collecting mud.[28]

The Voodoo revival of the late 20th century has drawn many of its deities from Haitian Vodou, where these divinities are called lwa. Among the lwa commonly venerated are Oshun, Ezili la Flambo, Erzuli Freda, Ogo, Mara, and Legba.[31]

These can be divided into separate nanchon (nations), such as the Rada and the Petwo. Glassman's New Orleans temple for instance has separate altars to the Rada and Petwo lwa.[32] Each of these is associated with particular items, colors, numbers, foodstuff, and drinks.[33] They are often considered to be intermediaries of God, who in Haitian Vodou is usually termed Le Bon Dieu.[27]

Ancestors and saints

The spirits of the dead played a prominent role in Louisiana Voodoo during the 19th century.[34] The prominence of these spirits of the dead may owe something to the fact that New Orleans' African American population was heavily descended from enslaved Kongolese, whose traditional religions placed emphasis on such spirits.[29] In the 21st century, Louisiana Voodoo has been characterized as a system of ancestor worship.[35] Communicating with the ancestors is an important part of its practice,[36] with these ancestral spirits often invoked during ceremonies.[37]

As Africans arrived in Louisiana, they adopted from Roman Catholicism and so various West African deities became associated with specific Roman Catholic saints. Interviews with elderly New Orleanians conducted in the 1930s and 1940s suggested that, as it existed in the closing three decades of the 19th century, Voodoo primarily entailed supplications to the saints for assistance.[39] Among the most popular was Saint Anthony of Padua; this figure is also the patron saint of the Kongo, a likely link to the heavily Kongo-descended population of New Orleans.[40] Rejecting the centrality of the saints for her 21st-century practice, Osbey has described these saints as "servants and messengers of the Ancestors."[26] She related that, unlike in Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería, the Roman Catholic saints retained their distinct identities rather than being equated with specific West African deities.[26]

The spirits of the dead played a prominent role in Louisiana Voodoo during the 19th century.[34] The prominence of these spirits of the dead may owe something to the fact that New Orleans' African American population was heavily descended from enslaved Kongolese, whose traditional religions placed emphasis on such spirits.[29] In the 21st century, Louisiana Voodoo has been characterized as a system of ancestor worship.[35] Communicating with the ancestors is an important part of its practice,[36] with these ancestral spirits often invoked during ceremonies.[37]

As Africans arrived in Louisiana, they adopted from Roman Catholicism and so various West African deities became associated with specific Roman Catholic saints.[38] Interviews with elderly New Orleanians conducted in the 1930s and 1940s suggested that, as it existed in the closing three decades of the 19th century, Voodoo primarily entailed supplications to the saints for assistance.[39] Among the most popular was Saint Anthony of Padua; this figure is also the patron saint of the Kongo, a likely link to the heavily Kongo-descended population of New Orleans.[40] Rejecting the centrality of the saints for her 21st-century practice, Osbey has described these saints as "servants and messengers of the Ancestors."[26] She related that, unlike in Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería, the Roman Catholic saints retained their distinct identities rather than being equated with specific West African deities.[26]

In its early 21st century form, Louisiana Voodoo accords particular respect to elders.[41]

Various commentators have described Louisiana Voodoo as matriarchal because of the dominant role priestesses have played in it.[42] Osbey described the religion as being "entirely within the sphere of women, whom we call Mothers."[43] The feminist theorist Tara Green defined the term "Voodoo Feminism" to describe instances whereby African American women drew upon both Louisiana Voodoo and conjure to resist racial and gender oppression that they experienced.[44] Michelle Gordon believed that the fact that free women of color dominated Voodoo in the 19th century represented a direct threat to the ideological foundations of "white supremacy and patriarchy."[45]

Practices-

Sacrifice was a recurring element of Louisiana Voodoo as it was historically practiced,[62] as it continues to be in Haitian Vodou.[63] Some 21st-century practitioners of Louisiana Voodoo do sacrifice animals in their rites, subsequently cooking and eating the carcass.[63] It is nevertheless not a universal practice in Louisiana Voodoo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

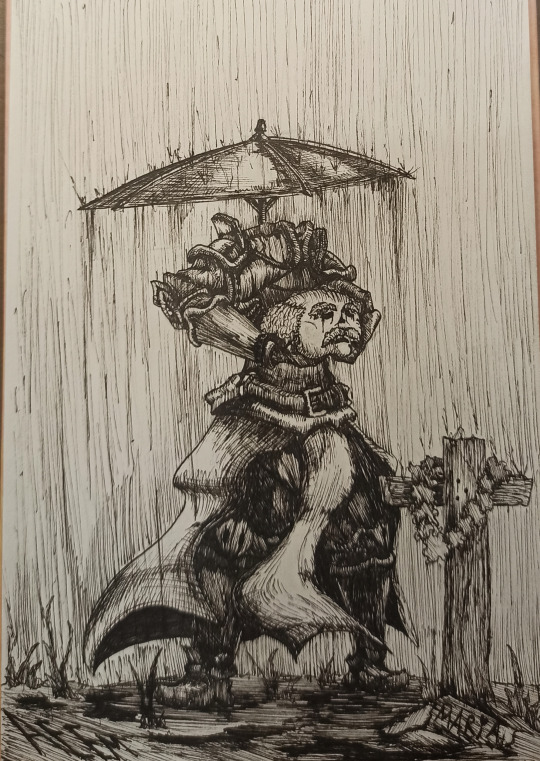

A History of Zombies

As requested by a lovely lovely friend of mine, here's an addition to my "history of" series! Today we're getting into the history of zombieeees!

If you haven't checked out my History of Vampires post, you can give it a read here <3

Art by ArtEmEvilMind on DeviantArt

What Is A Zombie?

"...a mythological undead corporeal revenant created through the reanimation of a corpse."

- Good ol' Wikipedia

Zombies are generally corpses that have come back to life through some means. In pop culture, most people will hear the word "zombie" and think of creatures that take over the world through virus-ridden bites and cannibalistic tendencies.

However, this completely erases the cultural origins of where the concept of zombies came from. For that, I think Tallahassee can sum up my feelings perfectly.

A History of "Zombies"

The term "zombie" originates from Haitian folklore, with the Haitian Creole word being zonbi. A zombie in this sense is a reanimated dead body that has typically been brought back through (CLOSED) magical means, particularly in the religion of Vodou. These reanimated corpses would act as servants under the will of a bokor, who has the ability to use said zombie's soul to enhance their own spiritual power. It was believed that God would eventually claim the soul of the zombie, making it a very temporary entity.

The English word "zombie" was first noted as being recorded in 1819, in a history of Brazil by the poet Robert Southey. This came in the form of the word "zombi". The Oxford English Dictionary testifies that the origins of the word is Central African, while some authors compare it specifically to the Kongo word "vumbi", meaning ghost or a corpse that retains the soul.