#kendall why you were such a genuine and nice youtuber

Text

Sigh. I love Kendall Rae's true crime content, but, lmao. She said in 2020 that she knows what an awful service "betterhelp" is and not at all suitable for someone in need of therapy etc, and she sold out just a week ago. Promoted them, and for what? Girl has millions of subscribers and gets very good views. Girl you HAVE money?? I'm so fucking disappointed, this is unbelievable. Every youtuber ever just ends up shilling out or being some god awful person

#The only youtubers I can trust are jacksepticeye and markiplier I swear to god#I cannot begin to express how disappointed I am#kendall why you were such a genuine and nice youtuber#fucking damn it#if she's so supportive of victims and their families then she might as well suggest betterhelp to them lmao#see how that goes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLACK FRIDAY SPOILERS!!

I’ve watched the show twice now so I’m gonna ramble some thoughts down before I go to bed.

I generally judge Starkid shows on 3 things: plot, characters and songs. I can’t fully judge the songs yet because of poor audio quality of the digital ticket but overall they were solid, standouts for me were ‘What do you say”, ‘Our Doors are open’ and ‘Deck the Halls of Northville High’. There was no Big Broadway Banger that blew me away but there was also no real forgettable songs either. Also there was a lot less Jeff falsetto, which was great (I physically cringed during ‘Monsters and Men’, you’re a good singer and a great song writer Jeff, I don’t know why you insist on doing it every show...) I also loved all of the choreography, there was some great James/Robert/Lauren dance breaks that were just excellent.

The characters were all wonderfully performed, we finally got the Lauren villain we have all been waiting for and Linda was just the worst person. I loved Tom and Becky and definitely consider Kim to be the MVP of the show. I was a little apprehensive of them casting a young teen for the first time but Kendall absolutely crushed it. All of the Starkid newcomers did a great job in this show. Also, Joey’s Uncle Wiley was just the right balance of seductive and sleazy. Let the man play these characters more, he’s so much better than just comic relief! (Also, THE SCENE, I really wasn’t ready for it)

As for the plot... I enjoyed the first act, with everyone going crazy trying to get their hands on a doll and hell breaking loose, but as soon as we got into the whole black and white thing with the President and McNamara I thought it went a little of the rails. I feel like all of the President’s scenes involving McNamara and the black and white didn’t add much to the show and only complicated the plot. They also introduced the idea of Lex and Hannah being ‘special’ and able to interact with the black and white but it didn’t really lead any where or get explained very well. And Webby? What was the point of that? I think they killed off Ethan too soon so it didn’t have as much of an impact, especially when he doesn’t get mentioned again for the rest of the show.

I’m also probably one of the few people who didn’t like all the GWDLM references. Having Emma and Paul at the beginning to establish the whole ‘alternate universe’ thing as well as give us some insight into Tom’s character was fine, but them showing up at the end to throw out a Hidgens’ mention didn’t do anything for me. Also, why did Bill, Charlotte and Mr Davidson show up at the end with no reason or explanation? It seems like maybe they’re setting up for a direct sequel but the ambiguous ending leaves it all up in the air.

Overall I thought Black Friday was good, but not great. 7/10. I know this post probably seems negative but I genuinely enjoyed the show a lot. A 7/10 Starkid show is still better than most of the crap that gets shown on TV and in cinemas these days. I’m still gonna buy the BTS package and watch it when it eventually comes to youtube.

It’s 2am and I’m drunk and tired, buy a digital ticket, don’t fucking bootleg the show, be nice to each other, stop underrating Starship and HMB, subscribe to the Tin Can Brothers.

#Team Starkid#blackfridaymusical#black friday spoilers#bf spoilers#lauren lopez#joey richter#jeff blim#robert manion#Curt Mega#kim whalen#jaime lyn beatty#dylan saunders#james tolbert#angela giarratana#kendall nicole yakshe#Corey Dorris#jon matteson

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

throw your head back laughing

pairing: chris kendall/pj liguori

rating: teen & up

tags: outsider pov, au, established relationship, idiots in love

word count: 1657

summary: Cara has to wonder how much of it is performative. Of course she does; everything she knows about this game points to them being in a Scene of some sort. They seem to genuinely enjoy each other's company, if nothing else.

written for the LOVELY @jestbee <3

happy goddamn birthday jane!!!!!! you’ve been such a good pal to me and i hope i can make you smile with this stupid thing!!!!!

read on ao3 or here!

"Hello, welcome to -" Cara cuts herself off in the middle of her spiel when she looks up from the podium. Two men stand in front of her for probably the ninth time this year, matching grins on their faces as they watch the recognition wash over her. She smiles, closer to a real one than a customer service one, and gestures behind her. "Your table is available. Do you need me to escort you?"

"Thanks, love," one of them says with a wink, "but I think we can manage."

He takes his companion by the sleeve and makes a beeline for a table near the middle of the restaurant, the same one they always go for. Cara bites back a laugh as she makes eye contact with one of the waitstaff.

Nate makes a big show of sighing and turning back around to tell the kitchen at large about their arrivals. She can't hear it from here, but Cara knows that people who have been here long enough are either thrilled or frustrated, and the new hires are probably just confused. When Nate is looking at her again, Cara taps her glasses and holds up three fingers. He makes a note on his order pad. She wonders how big the betting pool is going to be this time.

The men are, as always, ensconced in their own little world the moment their asses hit the seats. Their long legs overlap under the table in a comfortable, familiar sort of way, and they talk to each other with such dramatic hand gestures that Cara wishes she could hear the topic that's got them so riled up.

Sometimes she makes excuses to walk by their table and eavesdrop. So far she's learned that they're passionate about science fiction, craft supplies, what specific colour the ceiling is painted, and gender expression. It doesn't seem to matter if they're talking about the sliding scale of acceptable femininity for men to show in public or how easy it would be to build a robot out of cardboard - they have the same amount of enthusiasm, every time.

Cara has to wonder how much of it is performative. Of course she does; everything she knows about this game points to them being in a Scene of some sort. They seem to genuinely enjoy each other's company, if nothing else.

It's always a strange atmosphere for the first half hour or so after they've been seated. They talk and they eat and they seem oblivious to the wary eyes of the staff around them, even though anyone with half a brain knows they're fully aware of the attention on them. The only time they left without anything happening was when the place was practically empty and there was no audience of unsuspecting patrons for their nonsense.

That had been a different sort of anticipation. Like the whole building had been waiting for a beat that never dropped. The men had left without fanfare, and every employee had gone home perplexed.

The general consensus, up to that point, had been that they did this for the free food and champagne, but their need for some kind of audience opened up a Pandora's box of possible motivations. Nate's convinced that they're doing some sort of social experiment, one of the line chefs thinks they must be YouTubers or something, and a very optimistic new waitress has been positing that maybe it's genuine every time.

"Maybe one of them has short term memory problems," she'd explained to Cara. "Or they're very on-again off-again."

Cara had nodded along at the time, but she's not buying it. It's the grins on their faces every time they meet her at the hostess podium that convince her they know exactly what they're up to.

As far as Cara can tell, they might just do it for the hell of it.

Forty-something minutes after the men are seated, the signs start to show themselves. Cara drifts over to Nate and nudges him, interrupting his bussing for something much more entertaining. He grins and turns around. Neither of them make an effort to hide that they're staring, because it's happened seven or so times before.

The man in glasses is twitching like he's nervous, all of a sudden, and keeps patting at the same spot in his jacket. Cara might find it sweet if she hadn't seen it so many times.

"Ha," she whispers. "Told you it was him this time."

"They don't have a pattern," Nate argues. He's always a little prickly when he loses.

"But only one of them is wearing a jacket," Cara points out. "So obviously, it was going to be him. Is it a 50/50 split again?"

Nate sighs and shakes his head, pulling out his notepad as the men start talking in low voices across the small table. "No, most people guessed the other guy. You're only splitting the win with two of the cooks."

"Nice."

It seems like Nate wants to whinge some more, but then the man in glasses is standing up. The waitstaff all pause in what they're doing and turn to look, prompting the other diners to look as well. With hilariously awkward movements for how practised Cara knows the motion is, he drops to one knee and takes his companion's hand in both of his own. Some of the diners gasp or whisper amongst themselves; the waitstaff mostly just seem annoyed to lose the pool.

"Christopher," the man starts. His voice trembles the perfect amount, and Cara is reluctantly impressed by how sincere they make this seem every time.

"Oh my god," Christopher stage whispers. Cara wonders if that's actually his name.

"We've been friends for so long," the man continues, "and I've been so deeply in love with you for most of those years - I couldn't believe it when you first agreed to see a film with me in a non-platonic sort of way."

Out of the corner of his mouth, Nate murmurs, "What the hell is that accent? I can't place it for the life of me."

"Not sure," says Cara. "He just sort of sounds like he's on telly, doesn't he? Like a presenter?"

"D'you think there are hidden cameras?"

"Surely we'd have seen it somewhere if there were."

"But why else -"

"Shh," says Cara.

They're all so familiar with this song and dance that she knows Christopher is going to fan at his face with his free hand and then start tearing up. Watching him cry on demand is her favourite part. They can argue about motivations once they've left.

Sure enough, Christopher is wiping at his eyes and grinning down at his partner in crime. "Are you serious? Of course I'll marry you."

The other diners applaud politely when the men embrace. Cara makes a mental note of those who aren't, those who roll their eyes and mutter things to their companions, those who look upset when Christopher tugs the other man into a short, sweet kiss. She's not sure if it's a perk or a curse to know which of their regulars hate her, but it's certainly useful to know who to sit by the loo.

"Better bring them their celebratory fucking champagne," Nate sighs.

"Every goddamn time," Cara says, unable to hide the fondness in her voice. She can't help but root for these idiots. "Don't forget to comp their food."

"That's not even why they do this," says Nate. He's whinging, but Cara knows it's not actually a bother to him.

Nate's right; the free food and champagne clearly isn't the reason they've proposed to each other a half dozen times in the middle of their restaurant, but it's probably a bonus. Just like weeding out the homophobes on the staff is a bonus.

When everyone goes back to their dinners and their jobs and the newly-engaged-again men are back in their seats, Cara approaches them.

"Congratulations," she says, tucking her hair behind her ear. She sees the way Christopher's eyes linger on her interlocked Venus tattoo. He holds tighter to his fiancé's hand and gives her the same shit-eating grin as whenever they ask her for a table.

"Thanks, love."

"I'm Cara," she says, tapping at her name tag. "Just so you know how to address the invitation."

The man in glasses laughs, loud. He still seems like he's performing in some way, but a look passes between them and makes his voice softer, less put-on. "I promise that we would," he says, "except that we got married eight years ago."

Cara bites back a cackle of her own and shakes her head, trying not to make eye contact with any of her curious coworkers. She's definitely keeping this one to herself - you never know when another opportunity to win a betting pool will present itself, after all - so she doesn't exactly want to draw attention to the conversation.

"Alright," she says. "I better go back to work."

"Don't you want to know why we do this?" the man in glasses asks, sounding a bit put out.

Cara shrugs. "For the hell of it, right?"

Another look passes between them, and Christopher tips an invisible hat to her. "Pretty and smart, eh? Do you accept tips?"

Technically, no. And while she thinks she probably deserves one for this, Cara knows she's got a good chunk of everyone else's tip money tonight.

"Do you?" she asks instead. "Because I've got a tip for ya. You should try saying no next time."

"Saying no?" Christopher echoes, grinning across the table.

"We haven't tried that," his husband agrees. "Not as much fun, maybe, but surely the sympathy from it will make up for that."

"Plus, I can cry more."

Cara snorts and heads back to her podium. As curious as she is, she thinks it'll be more fun to wait and see how it pans out the next time they wander in to shake things up.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five Rules On How To Deal With A PR Crisis:

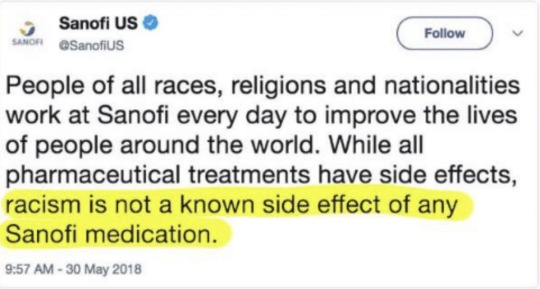

1) - Take Responsibility - the outcome of your reputation & image comes down to this first step. Do not try and point fingers. I repeat, do not try and point fingers! Take responsibility for your own actions. Respond to criticism. And keep the conversation positive. Don’t argue with critics. Don’t continue to dig the hole deeper. Remember Roseanne Barr’s PR scandal, involving a racial comment to a former Obama adviser? Yea, how well did that work out for her? She was fired from her hit TV show, effective immediately. At first, ABC was considering canceling the entire show altogether! But, the drama didn’t stop there; Rosanne went on trying to defend herself, claiming she had taken Ambien for sleep the night of that career-altering Tweet, claiming that she was “Not a racist, just an idiot who made a bad joke”. To add insult to injury, the pharmaceutical company Sanofi, the makers of Ambien, jumped in on the conversation tweeting this: “While all pharmaceutical treatments have side effects, racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication”. After Big Pharma joined the narrative, Rosannes mis-step had already gone viral. But after Sanofi got involved, the internet literally went berserk. Something that could have been avoided, had Rosanne kept her mouth shut about her comments. A heart-felt apology was all that she should have offered.

2) - Be Authentic - Now is not the time to try and manipulate your way out of the mess you’ve created. It’s also not wise to state conflicting accounts. Confusion is never received well. People don’t want to feel like they’re being misled, or manipulated. It really is as simple as taking responsibility for your actions, and issuing a genuine apology. Remember that Pepsi commercial, featuring Kendall Jenner fiasco? In the commercial, Pepsi gave the impression that the Black Lives Matter riots could be solved with handing an angry officer a nice, cold Pepsi. That’s so amazing, the poster of Pepsi! Why hadn’t I thought of that sooner? While many thought there was nothing wrong with Pepsi’s message, saying they thought it represented unity during a time of restlessness. Others were not so impressed, understandably so. People were being shot & killed by police, no apparent reason. Because of their skin color, and maybe because of the way they were dressed, or the kind of car they drive. Pepsi eventually admitted that they “Missed the mark”, but not before trying to publicly defend themselves, which didn’t go over too well with critics. In these situations, it’s best to just take accountability, apologize, and move on.

3) - Screw strategies - don’t wait until you’ve got a full-blown crisis on your hands before addressing the incident(s). Don’t take your good ol’ time trying to come up with the perfect strategy. This is instant reputation suicide. Recall the Queen after Diana died? The British public were enraged and offended that their Queen hadn’t issued a statement acknowledging Diana’s death. This left them feeling alone and isolated. Act fast!

4) - Be Genuine - People can see through bullshit. They can tell when they’re being manipulated or deceived. When you are dealing with an already enraged public, the last thing you want to do is add fuel to the fire. Be honest. Be relatable. And most importantly, be genuine. Peoples’ intuitions are quite perceptive these days. If you make a half-hearted apology, or point fingers at others for your mistakes, you are just making yourself look worse, and sabotaging your own reputation. When customers over at Yankee Candle started complaining to the company that their very expensive candles did not have the same intense scent-throw that Yankee Candles are beloved for, Yankee’s CEO at the time publicly came out and said that people didn’t care about the scent of their candles, claiming customers cared more about the design label & the exotic names of their scents. As you can imagine, this didn’t go over too well with Yankee Candle fans. Fun fact: the CEO who made this statement has since been replaced. 3 years later, and Yankee is still suffering the fallout of that CEO’s ignorant statement. Brand trust was compromised.

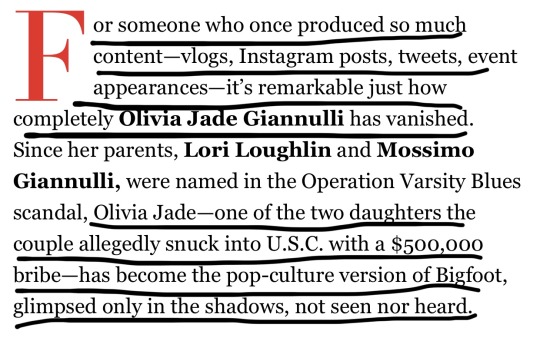

5) - Ask yourself “Why do I keep having so many PR faux pas”? - In my opinion, it seems like it would take more effort to keep having issues, than it would to just take a beat and disappear from the media, while the dust settles. This included ALL media platforms, like social media. You have enough press to deal with right now. You don’t need any more, whether that be good, bad, or indifferent. Recall the “Varsity Blues” college bribe scandal involving popular social media influencer Olivia Jade & her B list actress mother, Lori Laughlin? They didn’t mess around when that scandal hit headlines. Olivia went silent on social media, as did her mother. They have not been heard from at all. Even though Olivia has millions of subscribers on her YouTube channel, she has not uploaded another video since. This is the epitome of crisis PR management! Because they have been so silent, and have not created waves by giving opinionated interviews, they have virtually disappeared from headlines, and no one is talking about Varsity Blues anymore. Take a page from Olivia Jade, Meghan. At 18, she’s wise beyond her years.

These two need to start listening to the public’s criticism. They have failed miserably to acknowledge the people and their concerns. Social media isn’t working. Petitions aren’t working. Standing outside of the palace yelling “Charlatan Duchess” isn’t working. Would they notice if we sent smoke signals? Probably not. But we would get called “racists” for sending them.

#megxit#meghan markle#prince harry#royals#PR crisis#Shouty Duchess#duchess of deception#Demanding duchess#Beggin Meghan#Designer Duchess

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Would You Like Your Music News Madam?

Happy Wednesday all.

So with NME’s cutting its physical publication a few weeks back, it got me thinking about a chat I had with James Kendall founder of Brighton music publication Source Magazine. Back then The NME had just become free, now you will only find the publication online. When we spoke the fate of music journalism was quite similar to today but with the dwelling uncertainty of what would happen to physical publication. It’s fair to say as we put the NME magazine to rest, the direction is quite obvious. Oh well, save the trees n all.

We spoke during the creation of Revival so, yes this conversation is about two years old. Never the less this chat is still very much relevant, I think we touch on some very interesting topics James really showered me with his music journalist knowledge. I thought I’d only be genuine of me to let you into the research process behind ma baby blog, give you an insight into my noggin.

Basically, this interview is a lil gem and I want to share it with you lovely people.

Just in case, you didn’t get my awful pun the overall contentious is a discussion as to what is the prevailing platform for music journalism: physical vs online publication.

I had the idea that idea that the fanzine, the DIY publication was set to have a revival, in physical format but then I realised that maybe not, maybe it isn’t?

“People have started to appreciate objects again, people who grew up with the Internet are appreciating having something and that’s why vinyl records have had a revival.”

Yes exactly, I compared vinyl to the possible physical publication revival.

“Yes you are bang on with the vinyl analogy, it’s the same as with the cold craft beer thing people like things that have had some effort put into them, and things that have got no physical being are difficult to prove that effort, things that are so throw away. But to have something that someone’s put enough love into it to bother to get it printed or made makes a huge, huge difference. Saying that it is much more expensive to print a magazine, or fanzine that it is to build a website, which costs you exactly no money. So yeah there are people that are doing magazines, but there is probably less printed material that there was 5-10 years ago, the things that are being made are the more sorta’ special things. There’s an element of ‘people wanna’ make something that isn’t being represented, there’s no point making a fanzine that is similar to Q magazine. If you’re interested in feminist punk or some obscure music, it seems like hip hop and dance music are more of an online thing, and guitar music is the thing that’s more likely to be featured in a fanzine.”

I originally based my project on fanzines similar to ‘Sniffin’ Glue’ during the punk era but punk has derived and changed so much that it’s not what it used to be it’s not as DIY.

“I think there was a necessity for fanzines in that era to be physically printed, where are no if you’re really punk then you’re not making something that cost money you’re doing something in the cheapest way possible. Now a true punk aesthetic would now be online. There’s a sort of middle-classiness of fanzines now.”

Do you think if blogs where around then punks would use them?

“ When Sniffin’ Glue came out there was nowhere to read about punk, I’m not quite sure about the chronology of NME and The Melody Maker but there was nowhere. When The Sex Pistols where on The Paul Grundy Show it was a big sensation, it was shocking that they were on TV. There were no music programs apart from Top Of The Pops, there was nowhere to find out this stuff; so people had to make something - to talk about what they wanted to talk about. Now you could make a video, you could put something on YouTube, you could do a podcast, you could put something on a blog.”

I think the platforms changed the prevailing platform isn’t; really physical anymore like it was. Many people say they want physical nice things but at the end of the day, the internet has given everyone a platform to talk about things I guess...How do you think the internet has effected physical publications and music journalism?

“Massively, massively. In a way that I never expected when it came out, I thought it would be a threat to magazines cause of the speed of reviews coming out makes something like NME a week out of date as soon as it’s hit the newsstand. But that’s not how it’s affected, it is effected that if you wanna’ know what a song sounds like you go on the internet and find the song; and listen to it, and find out whether you like it or not.”

I guess you can review if yourself in that sense.

“Yeah, when I was sorta’ eighteen/nineteen the only way you could hear music and find out whether something was good or not, was by reading reviews. You had to know which review was shaped to your taste, which publications, you had to read a lot to figure out whether it was worth spending a tenner on a record. Music was more expensive in those days as well. So yeah it would be a big risk buying a record, some shops would let you listen to it on headphones, but if it was a busy Saturday probably not. So you kind of had to hang out in the record shop a lot, or you had to read a lot of music reviews. Now you could just go online and listen to it, and if you like it you can save it to your Spotify, or you can download it for 79p off Apple, or just play it again on YouTube, so you don’t need people to tell you if something’s any good or not. What you do need, is something that is similar, that is kinda a filter as to what is good. There’s 15,000 songs that come out in the week, and you can’t listen to all of them, so you need someone to help you through that, and that might be through a weekly compiled Spotify playlist or through somebody’s opinion. But the whole, reviewing an album to tell somebody whether it’s any good is not necessary anymore. There’s still an argument to say that music journalism is important, cause what music journalists can do that lots of other people can’t do, is they can contextualise something in the history of music, they can say whether it’s interesting with what’s gone one now and the past joining these links.”

Do you think in the way anyone can be a bedroom DJ, anyone can be a producer, anyone can make music.. so anyone can create a blog, do you think that has a negative effect on the industry because there’s an abundance of opinion?

“It would be a bit negative for me to say that other people can’t write about music, only the chosen few, of which, I’ve been one of those, that would be an awful attitude to have. The more people that write about music, the more good journalists discover that they can do this, and the better journalism should be overall. So yeah, it is the same as music... I mean dance music; it’s a prime example of this, when you had to get things pressed onto vinyl it has to be good enough for the label to spend £1000 to get it pressed. So there was a quality barrier there, and then as soon as Beat Port came around all of a sudden there's thousands and thousands of tracks every week, and loads of them haven’t got anything really important about them and will disappear. The fact that people are able to on a cheap computer - people were making records on PlayStations for a while. So the fact that there are kids on housing estates are able to make beats, and then their mates can rap over the top, then they get it out on beat port or iTunes, or, whatever is amazing. And the fact there is a kid on the same housing estate that can write about that on their phone, and update it to Tumblr, is an absolutely brilliant thing. Any old people that say it was better in my day are wrong. There are challenges is in every situation, but the fact that more people can access to their writing, and get their writing out there is the best thing that could possibly happen to journalism.”

Do you think there is a battle between physical and digital format, in terms of are people more inclined to read something online then buy something physical?

“People are definitely more included to read something online because of the speed of them. For example the NME might write a news story of Beyoncé falling of stage, and have a picture on physical format - if you read that online you probably will have a video of it, so that’s a better article not just cause it’s out there quicker, but because it’s a richer experience. Although it’s more difficult to read a long article online on your computer, there’s a reason why books are still around just as much. There are no distractions from other notifications, it’s easier on your eyes and it’s a nicer experience. There are different positives for physical and digital. I think what has happened, is people have decided that they’re either going to do physical publications or are going to focus on online, we’ll be known for one thing. Pitchfork is a great example. They’ve got enough readers to put out a magazine, and people would buy it but they’re concentrated on the online format. The NME is also interesting, they’ve been all about their website for quite a long while.”

Now the magazines free right?

Yes now the magazine is free, and that completely changes things. Now they’ve got a 1/3 of a million readers or print run that’s going out there, it seems to me that their website is doing a different thing to their magazine, and they don’t have a lot of cross over. You can’t look at the magazine online on issue, they do a preview but you can’t see the whole thing, which is really interesting. From an advertisers perspective, they want their adverts to be seen, so if they’re appearing on the digital version of issue that’s fine, but NME have decided they want people to pick up the physical magazine, that’s important to them. They’ve got both physical and digital but it’s not that same content.

Do you think all digital publications are all transferring online? Or the magazine will become free a like NME as well an online platform?

“ I used to have my own magazine, so I know how much it costs to print a magazine, and it’s a lot of money. So my magazine we did like 10/12,000 copies, on the lowest quality paper, like 60-90 pages, and it would cost somewhere between 3,000- 6,000 on printing. So that’s 3-6,000 pounds of adverts you’ve go to sell before you even break even.”

That was my main problem I faced with my project, funding and with my own experience I felt a blog was an alternative that did the job just as good. I just have an inkling that all publications will be online.

“Yeah. I find it interesting that the Independent has stopped printing, so it’s the first newspaper to shut down in thirty years or something so that’s really telling. But what happens to a shrunken advertising market for print publications is that when people split up their advertising budget they don’t put so much into print anymore. That print advert money is smaller, and as it filters through, the big print publications don’t suffer as much, but the smaller ones suffer massively. And that’s what happened to us, local adverts disappeared because of social media, a way of getting your message out there that’s free. So we replaced it with bigger brands and companies, but that sort of died out even though our print run was the same as ever, our readership was the same as ever, but we were getting less of that money as it wasn’t filtering through the magazine industry. And that’s why we went out of business, the magazine industry as a whole wasn’t big enough for us to take a share that was enough for us to do a good quality magazine. There are other local magazines, but I would argue that they are surviving, as they aren’t spending enough money making a decent project.”

Do you think major scale print publications are okay then?

“I think it’s become more and more difficult, even for major publications. Something like vogue, which is like 700 pages of advert - advertising is a sign of quality for them; they’re okay. If you look at something like Uncut Magazine it’s a lot thinner than it used to be, at one point it was so thin people stopped buying it. So it’s a spiral you get in, you haven’t got enough money to print such a good magazine, because you haven’t got many readers, then you haven’t got many readers cause your magazine isn’t as good, it’s a spiral and goes down and down until you go out of business. It is probably a good argument to say that paid for magazines will totally become free; I’m surprised by what the quality of the current NME, I’m surprised it’s doing so well. Shortlist and Stylist continue to do really well, and Time Out it struggled and firsts but it’s better than it’s been for years and years. So four of the most successful British magazines are all free. Everybody’s looking at that, everybody’s struggling. There will be some premium magazines that survive but everything else will be free. Lots of publications will try to go free, some people will make it some people won’t. To be a successful free magazine, you will probably have to be a big company, it will be big companies that provide successful free magazines - it won’t be the independent.”

I read ‘How To Write About Music” and it says that physical publications are just a regurgitation of PR

“ Nick Davies uncovered the phone-hacking scandal; he says that the problem with journalism (he’s talking about newspaper journalism) is the journalists don’t have enough time on a story to dig deep enough to find the truth they can only report what they are told. What is happening is that you are getting somebodies carefully PR’d opinion. That is definitely true about music journalism as well. If you don’t have enough time to devote to finding out what the truth is you are either rewriting a press release or you’re rewriting somebody else’s story.”

Do you think blogs are more passionate, more excited therefor it’s more of an honest raw opinion?

“ It is more honest but it has probably come from less knowledge. If I was writing about Slaves I probably no more about to roots of their music than the actual band themselves. But if you’re 15 and you’ve never heard punk before, and Slaves is the first band you’ve heard like that, it’s going to be very exciting prose and a very honest review, but it’s not going to have much depth. It was the same with me, I really loved Suede, and then I realised they were a rip off of David Bowie.”

I’m kind of focusing on that for my blog, I’m looking at the nature of revival and how we are living in a culture obsesses with it’s own past.

“Looking at it through that lens, it’s a retro thing again, were as when Sniffin Glue came out that wasn’t a very retro thing, it was cutting edge and modern. So if you are a punk band or a punk journalist that’s putting out fanzines it’s really you’re like; if you were about in the punk era you’d be writing about Jazz basically, because you are looking back at something that’s nearly 30-40 years old. When I was young it was at the tail end of the acid house era, people were kinda into this punk idea, but at the time It was dance music which was very DIY, on the edges of legality and that was the punk thing of the time. Not a revival or something that happened ten years ago. I think you could make an interesting point of the revival of fanzines and what they mean.”

Interesting, any last words?

“ So I think that blogs are the new fanzines; in terms of people who are not getting info on the sort of music that they like, people are writing blogs about it. People who are making fanzines have lost the DIY origin, its more about crafting something and making an object, whereas making a blog is about getting a voice out there and information about a subject that isn’t being portrayed in mainstream media. That’s how I would sum it up.”

#journalism#music industry#internet#blogging#music news#sniffin glue#fanzine#nme magazine#magazine#pr#the independent#top of the pops#ukmusic#punk

1 note

·

View note

Link

At the beginning of this year, I was using my iPhone to browse new titles on Amazon when I saw the cover of “How to Break Up With Your Phone” by Catherine Price. I downloaded it on Kindle because I genuinely wanted to reduce my smartphone use, but also because I thought it would be hilarious to read a book about breaking up with your smartphone on my smartphone (stupid, I know). Within a couple of chapters, however, I was motivated enough to download Moment, a screen time tracking app recommended by Price, and re-purchase the book in print.

Early in “How to Break Up With Your Phone,” Price invites her readers to take the Smartphone Compulsion Test, developed by David Greenfield, a psychiatry professor at the University of Connecticut who also founded the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction. The test has 15 questions, but I knew I was in trouble after answering the first five. Humbled by my very high score, which I am too embarrassed to disclose, I decided it was time to get serious about curtailing my smartphone usage.

Of the chapters in Price’s book, the one called “Putting the Dope in Dopamine” resonated with me the most. She writes that “phones and most apps are deliberately designed without ‘stopping cues’ to alert us when we’ve had enough—which is why it’s so easy to accidentally binge. On a certain level, we know that what we’re doing is making us feel gross. But instead of stopping, our brains decide the solution is to seek out more dopamine. We check our phones again. And again. And again.”

Gross was exactly how I felt. I bought my first iPhone in 2011 (and owned an iPod Touch before that). It was the first thing I looked at in the morning and the last thing I saw at night. I would claim it was because I wanted to check work stuff, but really I was on autopilot. Thinking about what I could have accomplished over the past eight years if I hadn’t been constantly attached to my smartphone made me feel queasy. I also wondered what it had done to my brain’s feedback loop. Just as sugar changes your palate, making you crave more and more sweets to feel sated, I was worried that the incremental doses of immediate gratification my phone doled out would diminish my ability to feel genuine joy and pleasure.

Price’s book was published in February, at the beginning of a year when it feels like tech companies finally started to treat excessive screen time as a liability (or at least do more than pay lip service to it). In addition to the introduction of Screen Time in iOS 12 and Android’s digital wellbeing tools, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube all launched new features that allow users to track time spent on their sites and apps.

Early this year, influential activist investors who hold Apple shares also called for the company to focus on how their devices impact kids. In a letter to Apple, hedge fund Jana Partners and California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) wrote “social media sites and applications for which the iPhone and iPad are a primary gateway are usually designed to be as addictive and time-consuming as possible, as many of their original creators have publicly acknowledged,” adding that “it is both unrealistic and a poor long-term business strategy to ask parents to fight this battle alone.”

The growing mound of research

Then in November, researchers at Penn State released an important new study that linked social media usage by adolescents to depression. Led by psychologist Melissa Hunt, the experimental study monitored 143 students with iPhones from the university for three weeks. The undergraduates were divided into two groups: one was instructed to limit their time on social media, including Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram, to just 10 minutes each app per day (their usage was confirmed by checking their phone’s iOS battery use screens). The other group continued using social media apps as they usually did. At the beginning of the study, a baseline was established with standard tests for depression, anxiety, social support and other issues, and each group continued to be assessed throughout the experiment.

The findings, published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, were striking. The researchers wrote that “the limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group.”

Even the control group benefitted, despite not being given limits on their social media use. “Both groups showed significant decreases in anxiety and fear of missing out over baselines, suggesting a benefit of increased self-monitoring,” the study said. “Our findings strongly suggest that limiting social media use to approximately 30 minutes a day may lead to significant improvement in well-being.”

Other academic studies published this year added to the growing roster of evidence that smartphones and mobile apps can significantly harm your mental and physical wellbeing.

A group of researchers from Princeton, Dartmouth, the University of Texas at Austin, and Stanford published a study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found using smartphones to take photos and videos of an experience actually reduces the ability to form memories of it. Others warned against keeping smartphones in your bedroom or even on your desk while you work. Optical chemistry researchers at the University of Toledo found that blue light from digital devices can cause molecular changes in your retina, potentially speeding macular degeneration.

So over the past 12 months, I’ve certainly had plenty of motivation to reduce my screen time. In fact, every time I checked the news on my phone, there seemed to be yet another headline about the perils of smartphone use. I began using Moment to track my total screen time and how it was divided between apps. I took two of Moment’s in-app courses, “Phone Bootcamp” and “Bored and Brilliant.” I also used the app to set a daily time limit, turned on “tiny reminders,” or push notifications that tell you how much time you’ve spent on your phone so far throughout the day, and enabled the “Force Me Off When I’m Over” feature, which basically annoys you off your phone when you go over your daily allotment.

At first I managed to cut my screen time in half. I had thought some of the benefits, like a better attention span mentioned in Price’s book, were too good to be true. But I found my concentration really did improve significantly after just a week of limiting my smartphone use. I read more long-form articles, caught up on some TV shows, and finished knitting a sweater for my toddler. Most importantly, the nagging feeling I had at the end of each day about frittering all my time away diminished, and so I lived happily after, snug in the knowledge that I’m not squandering my life on memes, clickbait and makeup tutorials.

Just kidding.

Holding my iPod Touch in 2010, a year before I bought my first smartphone and back when I still had an attention span.

After a few weeks, my screen time started creeping up again. First I turned off Moment’s “Force Me Off” feature, because my apartment doesn’t have a landline and I needed to be able to check texts from my husband. I kept the tiny reminders, but those became easier and easier to ignore. But even as I mindlessly scrolled through Instagram or Reddit, I felt the existentialist dread of knowing that I was misusing the best years of my life. With all that at stake, why is limiting screen time so hard?

I wish I knew how to quit you, small device

I decided to talk to the CEO of Moment, Tim Kendall, for some insight. Founded in 2014 by UI designer and iOS developer Kevin Holesh, Moment recently launched an Android version, too. It’s one of the best known of a genre that includes Forest, Freedom, Space, Off the Grid, AntiSocial and App Detox, all dedicated to reducing screen time (or at least encouraging more mindful smartphone use).

Kendall told me that I’m not alone. Moment has 7 million users and “over the last four years, you can see that average usage goes up every year,” he says. By looking at overall data, Moment’s team can tell that its tools and courses do help people reduce their screen time, but that often it starts creeping up again. Combating that with new features is one of the company’s main goals for next year.

“We’re spending a lot of time investing in R&D to figure out how to help people who fall into that category. They did Phone Bootcamp, saw nice results, saw benefits, but they just weren’t able to figure out how to do it sustainably,” says Kendall. Moment already releases new courses regularly (recent topics have included sleep, attention span, and family time) and recently began offering them on a subscription basis.

“It’s habit formation and sustained behavior change that is really hard,” says Kendall, who previously held positions as president at Pinterest and Facebook’s director of monetization. But he’s optimistic. “It’s tractable. People can do it. I think the rewards are really significant. We aren’t stopping with the courses. We are exploring a lot of different ways to help people.”

As Jana Partners and CalSTRS noted in their letter, a particularly important issue is the impact of excessive smartphone use on the first generation of teenagers and young adults to have constant access to the devices. Kendall notes that suicide rates among teenagers have increased dramatically over the past two decades. Though research hasn’t explicitly linked time spent online to suicide, the link between screen time and depression has been noted many times already, as in the Penn State study.

But there is hope. Kendall says that the Moment Coach feature, which delivers short, daily exercises to reduce smartphone use, seems to be particularly effective among millennials, the generation most stereotypically associated with being pathologically attached to their phones. “It seems that 20- and 30-somethings have an easier time internalizing the coach and therefore reducing their usage than 40- and 50-somethings,” he says.

Kendall stresses that Moment does not see smartphone use as an all-or-nothing proposition. Instead, he believes that people should replace brain junk food, like social media apps, with things like online language courses or meditation apps. “I really do think the phone used deliberately is one of the most wonderful things you have,” he says.

Researchers have found that taking smartphone photos and videos during an experience may decrease your ability to form memories of it. (Steved_np3/Getty Images)

I’ve tried to limit most of my smartphone usage to apps like Kindle, but the best solution has been to find offline alternatives to keep myself distracted. For example, I’ve been teaching myself new knitting and crochet techniques, because I can’t do either while holding my phone (though I do listen to podcasts and audiobooks). It also gives me a tactile way to measure the time I spend off my phone because the hours I cut off my screen time correlate to the number of rows I complete on a project. To limit my usage to specific apps, I rely on iOS Screen Time. It’s really easy to just tap “Ignore Limit,” however, so I also continue to depend on several of Moment’s features.

While several third-party screen time tracking app developers have recently found themselves under more scrutiny by Apple, Kendall says the launch of Screen Time hasn’t significantly impacted Moment’s business or sign ups. The launch of their Android version also opens up a significant new market (Android also enables Moment to add new features that aren’t possible on iOS, including only allowing access to certain apps during set times).

The short-term impact of iOS Screen Time has “been neutral, but I think in the long-term it’s really going to help,” Kendall says. “I think in the long-term it’s going to help with awareness. If I were to use a diet metaphor, I think Apple has built a terrific calorie counter and scale, but unfortunately they have not given people nutritional guidelines or a regimen. If you talk to any behavioral economist, not withstanding all that’s been said about the quantified self, numbers don’t really motivate people.”

Guilting also doesn’t work, at least not for the long-term, so Moment tries to take “a compassionate voice,” he adds. “That’s part of our brand and company and ethos. We don’t think we’ll be very helpful if people feel judged when we use our product. They need to feel cared for and supported, and know that the goal is not perfection, it’s gradual change.”

Many smartphone users are probably in my situation: alarmed by their screen time stats, unhappy about the time they waste, but also finding it hard to quit their devices. We don’t just use our smartphones to distract ourselves or get a quick dopamine rush with social media likes. We use it to manage our workload, keep in touch with friends, plan our days, read books, look up recipes, and find fun places to go. I’ve often thought about buying a Yondr bag or asking my husband to hide my phone from me, but I know that ultimately won’t help.

As cheesy as it sounds, the impetus for change must come from within. No amount of academic research, screen time apps, or analytics can make up for that.

One thing I tell myself is that unless developers find more ways to force us to change our behavior or another major paradigm shift occurs in mobile communications, my relationship with my smartphone will move in cycles. Sometimes I’ll be happy with my usage, then I’ll lapse, then I’ll take another Moment course or try another screen time app, and hopefully get back on track. In 2018, however, the conversation around screen time finally gained some desperately needed urgency (and in the meantime, I’ve actually completed some knitting projects instead of just thumbing my way through #knittersofinstagram).

from TechCrunch https://tcrn.ch/2EPgHLh

0 notes

Link

At the beginning of this year, I was using my iPhone to browse new titles on Amazon when I saw the cover of “How to Break Up With Your Phone” by Catherine Price. I downloaded it on Kindle because I genuinely wanted to reduce my smartphone use, but also because I thought it would be hilarious to read a book about breaking up with your smartphone on my smartphone (stupid, I know). Within a couple of chapters, however, I was motivated enough to download Moment, a screen time tracking app recommended by Price, and re-purchase the book in print.

Early in “How to Break Up With Your Phone,” Price invites her readers to take the Smartphone Compulsion Test, developed by David Greenfield, a psychiatry professor at the University of Connecticut who also founded the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction. The test has 15 questions, but I knew I was in trouble after answering the first five. Humbled by my very high score, which I am too embarrassed to disclose, I decided it was time to get serious about curtailing my smartphone usage.

Of the chapters in Price’s book, the one called “Putting the Dope in Dopamine” resonated with me the most. She writes that “phones and most apps are deliberately designed without ‘stopping cues’ to alert us when we’ve had enough—which is why it’s so easy to accidentally binge. On a certain level, we know that what we’re doing is making us feel gross. But instead of stopping, our brains decide the solution is to seek out more dopamine. We check our phones again. And again. And again.”

Gross was exactly how I felt. I bought my first iPhone in 2011 (and owned an iPod Touch before that). It was the first thing I looked at in the morning and the last thing I saw at night. I would claim it was because I wanted to check work stuff, but really I was on autopilot. Thinking about what I could have accomplished over the past eight years if I hadn’t been constantly attached to my smartphone made me feel queasy. I also wondered what it had done to my brain’s feedback loop. Just as sugar changes your palate, making you crave more and more sweets to feel sated, I was worried that the incremental doses of immediate gratification my phone doled out would diminish my ability to feel genuine joy and pleasure.

Price’s book was published in February, at the beginning of a year when it feels like tech companies finally started to treat excessive screen time as a liability (or at least do more than pay lip service to it). In addition to the introduction of Screen Time in iOS 12 and Android’s digital wellbeing tools, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube all launched new features that allow users to track time spent on their sites and apps.

Early this year, influential activist investors who hold Apple shares also called for the company to focus on how their devices impact kids. In a letter to Apple, hedge fund Jana Partners and California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) wrote “social media sites and applications for which the iPhone and iPad are a primary gateway are usually designed to be as addictive and time-consuming as possible, as many of their original creators have publicly acknowledged,” adding that “it is both unrealistic and a poor long-term business strategy to ask parents to fight this battle alone.”

The growing mound of research

Then in November, researchers at Penn State released an important new study that linked social media usage by adolescents to depression. Led by psychologist Melissa Hunt, the experimental study monitored 143 students with iPhones from the university for three weeks. The undergraduates were divided into two groups: one was instructed to limit their time on social media, including Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram, to just 10 minutes each app per day (their usage was confirmed by checking their phone’s iOS battery use screens). The other group continued using social media apps as they usually did. At the beginning of the study, a baseline was established with standard tests for depression, anxiety, social support and other issues, and each group continued to be assessed throughout the experiment.

The findings, published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, were striking. The researchers wrote that “the limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group.”

Even the control group benefitted, despite not being given limits on their social media use. “Both groups showed significant decreases in anxiety and fear of missing out over baselines, suggesting a benefit of increased self-monitoring,” the study said. “Our findings strongly suggest that limiting social media use to approximately 30 minutes a day may lead to significant improvement in well-being.”

Other academic studies published this year added to the growing roster of evidence that smartphones and mobile apps can significantly harm your mental and physical wellbeing.

A group of researchers from Princeton, Dartmouth, the University of Texas at Austin, and Stanford published a study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found using smartphones to take photos and videos of an experience actually reduces the ability to form memories of it. Others warned against keeping smartphones in your bedroom or even on your desk while you work. Optical chemistry researchers at the University of Toledo found that blue light from digital devices can cause molecular changes in your retina, potentially speeding macular degeneration.

So over the past 12 months, I’ve certainly had plenty of motivation to reduce my screen time. In fact, every time I checked the news on my phone, there seemed to be yet another headline about the perils of smartphone use. I began using Moment to track my total screen time and how it was divided between apps. I took two of Moment’s in-app courses, “Phone Bootcamp” and “Bored and Brilliant.” I also used the app to set a daily time limit, turned on “tiny reminders,” or push notifications that tell you how much time you’ve spent on your phone so far throughout the day, and enabled the “Force Me Off When I’m Over” feature, which basically annoys you off your phone when you go over your daily allotment.

At first I managed to cut my screen time in half. I had thought some of the benefits, like a better attention span mentioned in Price’s book, were too good to be true. But I found my concentration really did improve significantly after just a week of limiting my smartphone use. I read more long-form articles, caught up on some TV shows, and finished knitting a sweater for my toddler. Most importantly, the nagging feeling I had at the end of each day about frittering all my time away diminished, and so I lived happily after, snug in the knowledge that I’m not squandering my life on memes, clickbait and makeup tutorials.

Just kidding.

Holding my iPod Touch in 2010, a year before I bought my first smartphone and back when I still had an attention span.

After a few weeks, my screen time started creeping up again. First I turned off Moment’s “Force Me Off” feature, because my apartment doesn’t have a landline and I needed to be able to check texts from my husband. I kept the tiny reminders, but those became easier and easier to ignore. But even as I mindlessly scrolled through Instagram or Reddit, I felt the existentialist dread of knowing that I was misusing the best years of my life. With all that at stake, why is limiting screen time so hard?

I wish I knew how to quit you, small device

I decided to talk to the CEO of Moment, Tim Kendall, for some insight. Founded in 2014 by UI designer and iOS developer Kevin Holesh, Moment recently launched an Android version, too. It’s one of the best known of a genre that includes Forest, Freedom, Space, Off the Grid, AntiSocial and App Detox, all dedicated to reducing screen time (or at least encouraging more mindful smartphone use).

Kendall told me that I’m not alone. Moment has 7 million users and “over the last four years, you can see that average usage goes up every year,” he says. By looking at overall data, Moment’s team can tell that its tools and courses do help people reduce their screen time, but that often it starts creeping up again. Combating that with new features is one of the company’s main goals for next year.

“We’re spending a lot of time investing in R&D to figure out how to help people who fall into that category. They did Phone Bootcamp, saw nice results, saw benefits, but they just weren’t able to figure out how to do it sustainably,” says Kendall. Moment already releases new courses regularly (recent topics have included sleep, attention span, and family time) and recently began offering them on a subscription basis.

“It’s habit formation and sustained behavior change that is really hard,” says Kendall, who previously held positions as president at Pinterest and Facebook’s director of monetization. But he’s optimistic. “It’s tractable. People can do it. I think the rewards are really significant. We aren’t stopping with the courses. We are exploring a lot of different ways to help people.”

As Jana Partners and CalSTRS noted in their letter, a particularly important issue is the impact of excessive smartphone use on the first generation of teenagers and young adults to have constant access to the devices. Kendall notes that suicide rates among teenagers have increased dramatically over the past two decades. Though research hasn’t explicitly linked time spent online to suicide, the link between screen time and depression has been noted many times already, as in the Penn State study.

But there is hope. Kendall says that the Moment Coach feature, which delivers short, daily exercises to reduce smartphone use, seems to be particularly effective among millennials, the generation most stereotypically associated with being pathologically attached to their phones. “It seems that 20- and 30-somethings have an easier time internalizing the coach and therefore reducing their usage than 40- and 50-somethings,” he says.

Kendall stresses that Moment does not see smartphone use as an all-or-nothing proposition. Instead, he believes that people should replace brain junk food, like social media apps, with things like online language courses or meditation apps. “I really do think the phone used deliberately is one of the most wonderful things you have,” he says.

Researchers have found that taking smartphone photos and videos during an experience may decrease your ability to form memories of it. (Steved_np3/Getty Images)

I’ve tried to limit most of my smartphone usage to apps like Kindle, but the best solution has been to find offline alternatives to keep myself distracted. For example, I’ve been teaching myself new knitting and crochet techniques, because I can’t do either while holding my phone (though I do listen to podcasts and audiobooks). It also gives me a tactile way to measure the time I spend off my phone because the hours I cut off my screen time correlate to the number of rows I complete on a project. To limit my usage to specific apps, I rely on iOS Screen Time. It’s really easy to just tap “Ignore Limit,” however, so I also continue to depend on several of Moment’s features.

While several third-party screen time tracking app developers have recently found themselves under more scrutiny by Apple, Kendall says the launch of Screen Time hasn’t significantly impacted Moment’s business or sign ups. The launch of their Android version also opens up a significant new market (Android also enables Moment to add new features that aren’t possible on iOS, including only allowing access to certain apps during set times).

The short-term impact of iOS Screen Time has “been neutral, but I think in the long-term it’s really going to help,” Kendall says. “I think in the long-term it’s going to help with awareness. If I were to use a diet metaphor, I think Apple has built a terrific calorie counter and scale, but unfortunately they have not given people nutritional guidelines or a regimen. If you talk to any behavioral economist, not withstanding all that’s been said about the quantified self, numbers don’t really motivate people.”

Guilting also doesn’t work, at least not for the long-term, so Moment tries to take “a compassionate voice,” he adds. “That’s part of our brand and company and ethos. We don’t think we’ll be very helpful if people feel judged when we use our product. They need to feel cared for and supported, and know that the goal is not perfection, it’s gradual change.”

Many smartphone users are probably in my situation: alarmed by their screen time stats, unhappy about the time they waste, but also finding it hard to quit their devices. We don’t just use our smartphones to distract ourselves or get a quick dopamine rush with social media likes. We use it to manage our workload, keep in touch with friends, plan our days, read books, look up recipes, and find fun places to go. I’ve often thought about buying a Yondr bag or asking my husband to hide my phone from me, but I know that ultimately won’t help.

As cheesy as it sounds, the impetus for change must come from within. No amount of academic research, screen time apps, or analytics can make up for that.

One thing I tell myself is that unless developers find more ways to force us to change our behavior or another major paradigm shift occurs in mobile communications, my relationship with my smartphone will move in cycles. Sometimes I’ll be happy with my usage, then I’ll lapse, then I’ll take another Moment course or try another screen time app, and hopefully get back on track. In 2018, however, the conversation around screen time finally gained some desperately needed urgency (and in the meantime, I’ve actually completed some knitting projects instead of just thumbing my way through #knittersofinstagram).

from Mobile – TechCrunch https://tcrn.ch/2EPgHLh

ORIGINAL CONTENT FROM: https://techcrunch.com/

0 notes

Link

At the beginning of this year, I was using my iPhone to browse new titles on Amazon when I saw the cover of “How to Break Up With Your Phone” by Catherine Price. I downloaded it on Kindle because I genuinely wanted to reduce my smartphone use, but also because I thought it would be hilarious to read a book about breaking up with your smartphone on my smartphone (stupid, I know). Within a couple of chapters, however, I was motivated enough to download Moment, a screen time tracking app recommended by Price, and re-purchase the book in print.

Early in “How to Break Up With Your Phone,” Price invites her readers to take the Smartphone Compulsion Test, developed by David Greenfield, a psychiatry professor at the University of Connecticut who also founded the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction. The test has 15 questions, but I knew I was in trouble after answering the first five. Humbled by my very high score, which I am too embarrassed to disclose, I decided it was time to get serious about curtailing my smartphone usage.

Of the chapters in Price’s book, the one called “Putting the Dope in Dopamine” resonated with me the most. She writes that “phones and most apps are deliberately designed without ‘stopping cues’ to alert us when we’ve had enough—which is why it’s so easy to accidentally binge. On a certain level, we know that what we’re doing is making us feel gross. But instead of stopping, our brains decide the solution is to seek out more dopamine. We check our phones again. And again. And again.”

Gross was exactly how I felt. I bought my first iPhone in 2011 (and owned an iPod Touch before that). It was the first thing I looked at in the morning and the last thing I saw at night. I would claim it was because I wanted to check work stuff, but really I was on autopilot. Thinking about what I could have accomplished over the past eight years if I hadn’t been constantly attached to my smartphone made me feel queasy. I also wondered what it had done to my brain’s feedback loop. Just as sugar changes your palate, making you crave more and more sweets to feel sated, I was worried that the incremental doses of immediate gratification my phone doled out would diminish my ability to feel genuine joy and pleasure.

Price’s book was published in February, at the beginning of a year when it feels like tech companies finally started to treat excessive screen time as a liability (or at least do more than pay lip service to it). In addition to the introduction of Screen Time in iOS 12 and Android’s digital wellbeing tools, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube all launched new features that allow users to track time spent on their sites and apps.

Early this year, influential activist investors who hold Apple shares also called for the company to focus on how their devices impact kids. In a letter to Apple, hedge fund Jana Partners and California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) wrote “social media sites and applications for which the iPhone and iPad are a primary gateway are usually designed to be as addictive and time-consuming as possible, as many of their original creators have publicly acknowledged,” adding that “it is both unrealistic and a poor long-term business strategy to ask parents to fight this battle alone.”

The growing mound of research

Then in November, researchers at Penn State released an important new study that linked social media usage by adolescents to depression. Led by psychologist Melissa Hunt, the experimental study monitored 143 students with iPhones from the university for three weeks. The undergraduates were divided into two groups: one was instructed to limit their time on social media, including Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram, to just 10 minutes each app per day (their usage was confirmed by checking their phone’s iOS battery use screens). The other group continued using social media apps as they usually did. At the beginning of the study, a baseline was established with standard tests for depression, anxiety, social support and other issues, and each group continued to be assessed throughout the experiment.

The findings, published in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, were striking. The researchers wrote that “the limited use group showed significant reductions in loneliness and depression over three weeks compared to the control group.”

Even the control group benefitted, despite not being given limits on their social media use. “Both groups showed significant decreases in anxiety and fear of missing out over baselines, suggesting a benefit of increased self-monitoring,” the study said. “Our findings strongly suggest that limiting social media use to approximately 30 minutes a day may lead to significant improvement in well-being.”

Other academic studies published this year added to the growing roster of evidence that smartphones and mobile apps can significantly harm your mental and physical wellbeing.

A group of researchers from Princeton, Dartmouth, the University of Texas at Austin, and Stanford published a study in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found using smartphones to take photos and videos of an experience actually reduces the ability to form memories of it. Others warned against keeping smartphones in your bedroom or even on your desk while you work. Optical chemistry researchers at the University of Toledo found that blue light from digital devices can cause molecular changes in your retina, potentially speeding macular degeneration.

So over the past 12 months, I’ve certainly had plenty of motivation to reduce my screen time. In fact, every time I checked the news on my phone, there seemed to be yet another headline about the perils of smartphone use. I began using Moment to track my total screen time and how it was divided between apps. I took two of Moment’s in-app courses, “Phone Bootcamp” and “Bored and Brilliant.” I also used the app to set a daily time limit, turned on “tiny reminders,” or push notifications that tell you how much time you’ve spent on your phone so far throughout the day, and enabled the “Force Me Off When I’m Over” feature, which basically annoys you off your phone when you go over your daily allotment.

At first I managed to cut my screen time in half. I had thought some of the benefits, like a better attention span mentioned in Price’s book, were too good to be true. But I found my concentration really did improve significantly after just a week of limiting my smartphone use. I read more long-form articles, caught up on some TV shows, and finished knitting a sweater for my toddler. Most importantly, the nagging feeling I had at the end of each day about frittering all my time away diminished, and so I lived happily after, snug in the knowledge that I’m not squandering my life on memes, clickbait and makeup tutorials.

Just kidding.

Holding my iPod Touch in 2010, a year before I bought my first smartphone and back when I still had an attention span.

After a few weeks, my screen time started creeping up again. First I turned off Moment’s “Force Me Off” feature, because my apartment doesn’t have a landline and I needed to be able to check texts from my husband. I kept the tiny reminders, but those became easier and easier to ignore. But even as I mindlessly scrolled through Instagram or Reddit, I felt the existentialist dread of knowing that I was misusing the best years of my life. With all that at stake, why is limiting screen time so hard?

I wish I knew how to quit you, small device

I decided to talk to the CEO of Moment, Tim Kendall, for some insight. Founded in 2014 by UI designer and iOS developer Kevin Holesh, Moment recently launched an Android version, too. It’s one of the best known of a genre that includes Forest, Freedom, Space, Off the Grid, AntiSocial and App Detox, all dedicated to reducing screen time (or at least encouraging more mindful smartphone use).

Kendall told me that I’m not alone. Moment has 7 million users and “over the last four years, you can see that average usage goes up every year,” he says. By looking at overall data, Moment’s team can tell that its tools and courses do help people reduce their screen time, but that often it starts creeping up again. Combating that with new features is one of the company’s main goals for next year.

“We’re spending a lot of time investing in R&D to figure out how to help people who fall into that category. They did Phone Bootcamp, saw nice results, saw benefits, but they just weren’t able to figure out how to do it sustainably,” says Kendall. Moment already releases new courses regularly (recent topics have included sleep, attention span, and family time) and recently began offering them on a subscription basis.

“It’s habit formation and sustained behavior change that is really hard,” says Kendall, who previously held positions as president at Pinterest and Facebook’s director of monetization. But he’s optimistic. “It’s tractable. People can do it. I think the rewards are really significant. We aren’t stopping with the courses. We are exploring a lot of different ways to help people.”

As Jana Partners and CalSTRS noted in their letter, a particularly important issue is the impact of excessive smartphone use on the first generation of teenagers and young adults to have constant access to the devices. Kendall notes that suicide rates among teenagers have increased dramatically over the past two decades. Though research hasn’t explicitly linked time spent online to suicide, the link between screen time and depression has been noted many times already, as in the Penn State study.

But there is hope. Kendall says that the Moment Coach feature, which delivers short, daily exercises to reduce smartphone use, seems to be particularly effective among millennials, the generation most stereotypically associated with being pathologically attached to their phones. “It seems that 20- and 30-somethings have an easier time internalizing the coach and therefore reducing their usage than 40- and 50-somethings,” he says.

Kendall stresses that Moment does not see smartphone use as an all-or-nothing proposition. Instead, he believes that people should replace brain junk food, like social media apps, with things like online language courses or meditation apps. “I really do think the phone used deliberately is one of the most wonderful things you have,” he says.

Researchers have found that taking smartphone photos and videos during an experience may decrease your ability to form memories of it. (Steved_np3/Getty Images)

I’ve tried to limit most of my smartphone usage to apps like Kindle, but the best solution has been to find offline alternatives to keep myself distracted. For example, I’ve been teaching myself new knitting and crochet techniques, because I can’t do either while holding my phone (though I do listen to podcasts and audiobooks). It also gives me a tactile way to measure the time I spend off my phone because the hours I cut off my screen time correlate to the number of rows I complete on a project. To limit my usage to specific apps, I rely on iOS Screen Time. It’s really easy to just tap “Ignore Limit,” however, so I also continue to depend on several of Moment’s features.

While several third-party screen time tracking app developers have recently found themselves under more scrutiny by Apple, Kendall says the launch of Screen Time hasn’t significantly impacted Moment’s business or sign ups. The launch of their Android version also opens up a significant new market (Android also enables Moment to add new features that aren’t possible on iOS, including only allowing access to certain apps during set times).

The short-term impact of iOS Screen Time has “been neutral, but I think in the long-term it’s really going to help,” Kendall says. “I think in the long-term it’s going to help with awareness. If I were to use a diet metaphor, I think Apple has built a terrific calorie counter and scale, but unfortunately they have not given people nutritional guidelines or a regimen. If you talk to any behavioral economist, not withstanding all that’s been said about the quantified self, numbers don’t really motivate people.”

Guilting also doesn’t work, at least not for the long-term, so Moment tries to take “a compassionate voice,” he adds. “That’s part of our brand and company and ethos. We don’t think we’ll be very helpful if people feel judged when we use our product. They need to feel cared for and supported, and know that the goal is not perfection, it’s gradual change.”

Many smartphone users are probably in my situation: alarmed by their screen time stats, unhappy about the time they waste, but also finding it hard to quit their devices. We don’t just use our smartphones to distract ourselves or get a quick dopamine rush with social media likes. We use it to manage our workload, keep in touch with friends, plan our days, read books, look up recipes, and find fun places to go. I’ve often thought about buying a Yondr bag or asking my husband to hide my phone from me, but I know that ultimately won’t help.

As cheesy as it sounds, the impetus for change must come from within. No amount of academic research, screen time apps, or analytics can make up for that.

One thing I tell myself is that unless developers find more ways to force us to change our behavior or another major paradigm shift occurs in mobile communications, my relationship with my smartphone will move in cycles. Sometimes I’ll be happy with my usage, then I’ll lapse, then I’ll take another Moment course or try another screen time app, and hopefully get back on track. In 2018, however, the conversation around screen time finally gained some desperately needed urgency (and in the meantime, I’ve actually completed some knitting projects instead of just thumbing my way through #knittersofinstagram).

via TechCrunch

0 notes

Text

We finally started taking screen time seriously in 2018

At the beginning of this year, I was using my iPhone to browse new titles on Amazon when I saw the cover of “How to Break Up With Your Phone” by Catherine Price. I downloaded it on Kindle because I genuinely wanted to reduce my smartphone use, but also because I thought it would be hilarious to read a book about breaking up with your smartphone on my smartphone (stupid, I know). Within a couple of chapters, however, I was motivated enough to download Moment, a screen time tracking app recommended by Price, and re-purchase the book in print.