#joe flannery

Text

Brian Epstein in 1938 & in 1965

Brian was almost exactly three years younger than myself (born 19 September 1934) and was only a pre-school squirt to me, being all of about 3 or 4 years old and looking very Jewish. He was quite a handful and I thought at the time something of a spoiled brat. So much that in fact he had me in tears by the end of that afternoon. I had attempted to play with his brand new toy: a coronation coach, which was like a piece of crown jewellery to me. Before even getting a whiff of a chance, Brian deliberately trod on the lead horses, breaking their legs, rather than having it distract my attention from him. I was horrified, but also petrified because I naturally assumed that, being the eldest, I would get the blame for this act of wanton destruction. I need not have worried, however, because when Queenie returned nothing was said at all. Brian obviously always got what he wanted and the ruined coach wasn’t even mentioned. - Joe Flannery

#brian epstein#joe flannery#one of my fav quotes from his book#i can see that lovely little child destroying a precious expensive toy so vividly#brian#quote#m

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HAPPY BIRTHDAY BRIAN EPSTEIN!

“…no one else was going to stack up against Brian in my mind. No one would ever be able to do it as good because you couldn’t have the flare, the panache, the wit, the intelligence Brian had. Anyone else would just merely be a money manager. Brian was far more than that." - Paul McCartney

“If he walked into a full room, people would want to know, ‘Who’s that?’ He was so visual and bright.” Joe Flannery

“Brian believed sincerely in the philosophy of flower-power, of love and peace and bells. Often he dressed in a psychedelically-patterned shirt, and frequently referred to his friends in letters as ‘beautiful people’. This was not merely a affectation of the period. Before entering the Army he had talked of being a conscientious objector to military service he had always evangelized for world peace.” Ray Coleman

“Brian was much more than a brilliant businessman. He was a spiritual centre.” - Marianne Faithfull

#Brian Epstein#Brian#quotes#Paul McCartney#Joe Flannery#Ray Coleman#Marianne Faithfull#thebeatlesedit#Happy Birthday darling ❤️#eppysgifs

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

[George] was like that: quiet, unassuming, occasionally moody and certainly introverted - an odd combination for a rock and roller! At Gardner Road you wouldn't even notice him sitting in a room most of the time. He sat, listened, laughed, drank tea, ate buttered toast, just the same as everybody else, but you would find it difficult to remember whether he had been there moments after he had gone.

Place a guitar in his hands, however, and he would grow in confidence immediately. It almost seemed as if he had also grown in stature, the change was so remarkable.

Standing in the Wings, by Joe Flannery (with Mike Brocken)

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dianne Feinstein, the woman who represented California in the US Senate and was the longest-serving female senator in history, “blazed trails for women in politics and found a life’s calling in public service”, Hillary Clinton said.

The former New York Senator and Secretary of State, who in 2016 was the first woman to win the presidential nomination of a major US party, paid tribute to her fellow Democrat shortly after the announcement of her death. At the time of her death, Feinstein was 90 and still in office.

Clinton added: “I’ll miss her greatly as a friend and colleague.”

From the White House, Joe Biden saluted “a pioneering American.”

The President added: “Serving in the Senate together for more than 15 years, I had a front-row seat to what Dianne was able to accomplish. It’s why I recruited her to serve on the Judiciary Committee when I was chairman – I knew what she was made of.”

“… Often the only woman in the room, Dianne was a role model for so many Americans … she had an immense impact on younger female leaders for whom she generously opened doors. Dianne was tough, sharp, always prepared, and never pulled a punch, but she was also a kind and loyal friend.”

Gavin Newsom, the Democratic Governor of California, will select Feinstein’s replacement. Calling Feinstein “a political giant”, he said she “was many things – a powerful, trailblazing US Senator; an early voice for gun control; a leader in times of tragedy and chaos.”

“But to me, she was a dear friend, a lifelong mentor, and a role model not only for me, but to my wife and daughters for what a powerful, effective leader looks like.”

Feinstein’s “tenacity”, Newsom said, “was matched by her grace. She broke down barriers and glass ceilings, but never lost her belief in the spirit of political cooperation. And she was a fighter - for the city [San Francisco, where she was the first woman to be mayor], the state and the country she loved.”

There was some discord among the praise. David Axelrod, formerly a senior adviser to Barack Obama, pointed to recent controversy over whether, given her evidently failing health and absences which affected Democratic Senate business, Feinstein should have retired.

“How sad that the final, painful years will eclipse in the memories of some a long and distinguished career,” Axelrod said. “RIP, Senator Feinstein.”

Many users cited a recent piece in New York magazine by the writer Rebecca Traister, about Feinstein’s declining years, which asked: “She fought for gun control, civil rights and abortion access for half a century. Where did it all go wrong?”

John Flannery, a former federal prosecutor turned commentator, was among those who had a rejoinder: “I hope some of those who hounded her in her dying days will remember her contributions.”

Many tributes highlighted Feinstein’s contributions to attempts to combat the problem of gun violence.

Though Feinstein “made her mark on everything from national security to the environment to protecting civil liberties”, Biden said, “there’s no better example of her skillful legislating and sheer force of will than when she turned passion into purpose, and led the fight to ban assault weapons.”

Chris Murphy, a Democratic Senator from Connecticut and a leading voice for gun control reform, said Feinstein would “go down as a heroic, historic American leader … an early and fearless champion of the gun safety movement as author of the monumental Assault Weapons Ban of 1994.”

“For a long time, between 1994 and the tragedy in Newtown in 2012 [in which 20 young children and six adults were killed], Dianne was often a lonely but unwavering voice on the issue of gun violence.”

“The modern anti-gun violence movement – now more powerful than the gun lobby – simply would not exist without Dianne’s moral leadership.”

From the US House, Maxwell Frost of Florida, one of the youngest congressional progressives, called Feinstein “a champion for gun violence prevention that broke barriers at all levels of government.”

“We wouldn’t have had an assault weapons ban if it wasn’t for Senator Feinstein and due to her tireless work, we will win it back. May her memory be a blessing.”

From outside Congress, Shannon Watts, founder of Moms Demand Action, a pro-gun control group, pointed out that Feinstein was “one of the first among her colleagues to support gun safety – including Democrats”.

Inside Congress, as a government shutdown loomed, Feinstein’s desk in the Senate was draped in black cloth, a vase of white roses placed to mark her death.

From the other side of the political aisle, the Maine Republican Senator Susan Collins called Feinstein “a strong and effective leader, and a good friend.”

Newsom has pledged to pick a Black woman to replace Feinstein until the midterm elections next year.

On Friday, Barbara Lee, a Black Democratic congresswoman running for the seat, said: “This is a sad day for California and the nation. Senator Feinstein was a champion for our state, and served as the voice of a political revolution for women.”

Among commentators, the MSNBC anchor Mehdi Hasan highlighted what will to many prove a complicated political legacy.

“The high point and low point of … Feinstein’s long and storied career as a US senator both relate to the ‘War On Terror’,” Hasan said. “Low point: voting for the Iraq invasion. High point: going against the CIA to expose their torture programme.”

In his statement, Newsom said: “Every race [Feinstein] won, she made history, but her story wasn’t just about being the first woman in a particular political office, it was what she did for California, and for America, with that power once she earned it. That’s what she should be remembered for.”

“There is simply nobody who possessed the poise, gravitas, and fierceness of Dianne Feinstein.”

Jennifer Mercieca, a historian of political rhetoric at Texas A&M University, put the case for Feinstein perhaps most simply of all.

“Dianne Feinstein was on the right side of history,” she said.

#us politics#news#the guardian#rip#sen. dianne feinstein#Democrats#us senate#Hillary Clinton#president joe biden#gov. Gavin Newsom#David Axelrod#California#Rebecca Traister#John Flannery#1994 assault weapons ban#gun control#gun rights#gun reform#sen. chris Murphy#rep. Maxwell Frost#Shannon Watts#Moms Demand Action#sen. Susan Collins#rep. Barbara Lee#Mehdi Hasan#msnbc#twitter#tweet#x#Jennifer Mercieca

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

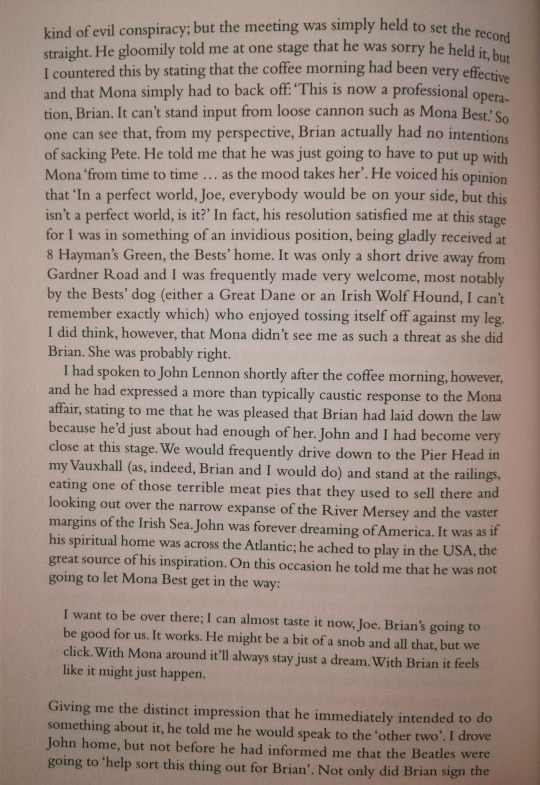

Brian holding a coffee morning for female compagnions and relatives of his artists, Beatles trying to get rid of Mona Best more than Pete, John saying they’d help sort this thing out for Brian and then they make him fire Pete after all, and the heartache of the USA conversation... - this is a lot.

#random reading#very niche beatles interests#very lousy pictures of the text because i am too lazy to move from the couch#it's been a numbing day :(#it's joe flannery btw not sure if that is identifiable from the text

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

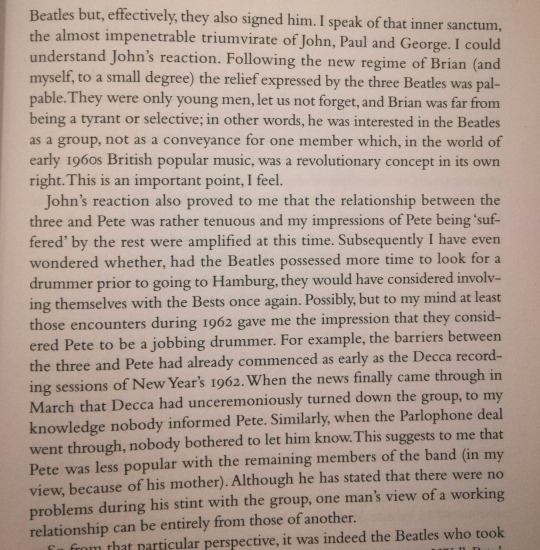

Gangs of London, Season One (2020)

Directed by Gareth Evans, Corin Hardy & Xavier Gens, Cinematography by Matt Flannery, Martijn van Broekhuizen & Laurent Barès

#scenesandscreens#gangs of london#gareth evans#corin hardy#Matt Flannery#Martijn van Broekhuizen#Laurent Barès#joe cole#colm meaney#lucian msamati#sope dirisu#michelle fairley#brian vernel#valene kane#paapa essiedu#pippa bennett warner#Asif Raza Mir#orli shuka#narges rashidi#Mark Lewis Jones#ray panthaki#jing lusi#waleed zuaiter#fady elsayed

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gangs of London

(S02E02)

#gangs of london#gareth evans#Matt Flannery#tv series#joe cole#sope dirisu#michelle fairley#lucian msamati#2022#british tv series

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest star Shelby Flannery sharing some BTS pics of the 1,000th ep! So happy to see Joe Spano, can't wait to have Fornell back 😍

Also, Gary Cole. Like, just-- GARY COLE. 🔥

#ncis#ncis 1000th ep#ncis bts#ncis new ep#gary cole#joe spano#sean Murray#wilmer valderrama#katrina law#alden parker#tobias fornell#tim mcgee#nick torres#jessica knight

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

““Dorothy reminds me in so many ways of Toni Morrison,” West said. “You know Toni Morrison is Catholic. Many people do not realize that she is one of the great Catholic writers. Like Flannery O’Connor, she has an incarnational conception of human existence. We Protestants are too individualistic. I think we need to learn from Catholics who are always centered on community.”

(…)

She viewed belief in God as “an intellectual experience that intensifies our perceptions and distances us from an egocentric and predatory life, from ignorance and from the limits of personal satisfactions”—and affirmed her Catholic identity. “I had a moment of crisis on the occasion of Vatican II,” she said. “At the time I had the impression that it was a superficial change, and I suffered greatly from the abolition of Latin, which I saw as the unifying and universal language of the Church.”

Morrison saw a problematic absence of authentic religion in modern art: “It’s not serious—it’s supermarket religion, a spiritual Disneyland of false fear and pleasure.” She lamented that religion is often parodied or simplified, as in “those pretentious bad films in which angels appear as dei ex machina, or of figurative artists who use religious iconography with the sole purpose of creating a scandal.” She admired the work of James Joyce, especially his earlier works, and had a particular affinity for Flannery O’Connor, “a great artist who hasn’t received the attention she deserves.”

What emerges from Morrison’s public discussions of faith is paradoxical Catholicism. Her conception of God is malleable, progressive, and esoteric. She retained a distinct nostalgia for Catholic ritual, and feels the “greatest respect” for those who practice the faith, even if she herself wavered. In a 2015 interview with NPR, Morrison said there was not a “structured” sense of religion in her life at the moment, but “I might be easily seduced to go back to church because I like the controversy as well as the beauty of this particular Pope Francis. He’s very interesting to me.”

Morrison’s Catholic faith—individual and communal, traditional and idiosyncratic—offers a theological structure for her worldview. Her Catholicism illuminates her fiction; in particular, her views of bodies, and the narrative power of stories. An artist, Morrison affirmed, “bears witness.” Her father’s ghost stories, her mother’s spiritual musicality, and her own youthful sense of attraction to Christianity’s “scriptures and its vagueness” led her to conclude it is “a theatrical religion. It says something particularly interesting to black people, and I think it’s part of why they were so available to it. It was the love things that were psychically very important. Nobody could have endured that life in constant rage.” Morrison said it is a sense of “transcending love” that makes “the New Testament . . . so pertinent to black literature—the lamb, the victim, the vulnerable one who does die but nevertheless lives.”

(…)

Morrison is describing a Catholic style of storytelling here, reflected in the various emotional notes of Mass. The religion calls for extremes: solemnity, joy, silence, and exhortation. Such a literary approach is audacious, confident, and necessary, considering Morrison’s broader goals. She rejected the term experimental, clarifying “I am simply trying to recreate something out of an old art form in my books—the something that defines what makes a book ‘black.’”

(…)

Morrison was both storyteller and archivist. Her commitment to history and tradition itself feels Catholic in orientation. She sought to “merge vernacular with the lyric, with the standard, and with the biblical, because it was part of the linguistic heritage of my family, moving up and down the scale, across it, in between it.” When a serious subject came up in family conversation, “it was highly sermonic, highly formalized, biblical in a sense, and easily so. They could move easily into the language of the King James Bible and then back to standard English, and then segue into language that we would call street.”

Language was play and performance; the pivots and turns were “an enhancement for me, not a restriction,” and showed her that “there was an enormous power” in such shifts. Morrison’s attention toward language is inherently religious; by talking about the change from Latin to English Mass as a regrettable shift, she invokes the sense that faith is both content and language; both story and medium.

From her first novel on forward, Morrison appeared intent on forcing us to look at embodied black pain with the full power of language. As a Catholic writer, she wanted us to see the body on the cross; to see its blood, its cuts, its sweat. That corporal sense defines her novel Beloved (1988), perhaps Morrison’s most ambitious, stirring work. “Black people never annihilate evil,” Morrison has said. “They don’t run it out of their neighborhoods, chop it up, or burn it up. They don’t have witch hangings. They accept it. It’s almost like a fourth dimension in their lives.”

(…)

Morrison has said that all of her writing is “about love or its absence.” There must always be one or the other—her characters do not live without ebullience or suffering. “Black women,” Morrison explained, “have held, have been given, you know, the cross. They don’t walk near it. They’re often on it. And they’ve borne that, I think, extremely well.” No character in Morrison’s canon lives the cross as much as Sethe, who even “got a tree on my back” from whipping. Scarred inside and out, she is the living embodiment of bearing witness.

(…)

Morrison’s Catholicism was one of the Passion: of scarred bodies, public execution, and private penance. When Morrison thought of “the infiniteness of time, I get lost in a mixture of dismay and excitement. I sense the order and harmony that suggest an intelligence, and I discover, with a slight shiver, that my own language becomes evangelical.” The more Morrison contemplates the grandness and complexity of life, the more her writing reverts to the Catholic storytelling methods that enthralled her as a child and cultivated her faith. This creates a powerful juxtaposition: a skilled novelist compelled to both abstraction and physicality in her stories. Catholicism, for Morrison, offers a language to connect these differences.

For Morrison, the traits of black language include the “rhythm of a familiar, hand-me-down dignity [that] is pulled along by an accretion of detail displayed in a meandering unremarkableness.” Syntax that is “highly aural” and “parabolic.” The language of Latin Mass—its grandeur, silences, communal participation, coupled with the congregation’s performative resurrection of an ancient tongue—offers a foundation for Morrison’s meticulous appreciation of language.

Her representations of faith—believers, doubters, preachers, heretics, and miracles—are powerful because of her evocative language, and also because she presents them without irony. She took religion seriously. She tended to be self-effacing when describing her own belief, and it feels like an action of humility. In a 2014 interview, she affirmed “I am a Catholic” while explaining her willingness to write with a certain, frank moral clarity in her fiction. Morrison was not being contradictory; she was speaking with nuance. She might have been lapsed in practice, but she was culturally—and therefore socially, morally—Catholic.

The same aesthetics that originally attracted Morrison to Catholicism are revealed in her fiction, despite her wavering of institutional adherence. Her radical approach to the body also makes her the greatest American Catholic writer about race. That one of the finest, most heralded American writers is Catholic—and yet not spoken about as such—demonstrates why the status of lapsed Catholic writers is so essential to understanding American fiction.

A faith charged with sensory detail, performance, and story, Catholicism seeps into these writers’ lives—making it impossible to gauge their moral senses without appreciating how they refract their Catholic pasts. The fiction of lapsed Catholic writers suggests a longing for spiritual meaning and a continued fascination with the language and feeling of faith, absent God or not: a profound struggle that illuminates their stories, and that speaks to their readers.”

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

"John and I then enjoyed a lengthy conversation. We talked a lot of rubbish, of course – he called me 'Flo' after one of his aforementioned wordplays: 'Flo Jannery'. He was very well and happy, but he missed Liverpool, he missed 'the others' and he missed London 'after a fashion', but he told me at one stage that he regretted ‘getting too political'. He said that he had made a bit of a 'tit of himself'. I told him not to worry: I had been defending him locally at least. We came to reminisce about our times sitting at the Pier Head, eating crap pies and him wanting to go 'over there', meaning the United States. I also informed him of my partnership with Clive and he was very interested in this; in fact, he was excited. 'That sounds good,' he said. 'We should start talking about me coming home before that bastard Nixon gets me.' I was rather taken aback by this comment and asked him to explain. John launched into a diatribe against the former president. He appeared convinced that even out of office Nixon carried power and wanted him dead; he felt that some kind of curse was hanging over him. It was not any kind of wizardry to which John referred, but his thoughts that the US government was effectively out to get him. It was clear to me that John was not simply expressing his generation's deep concern about Richard Nixon and his presidency, but all of the machinations of the political establishment of the US. His tone bothered me a little, expressing as it did what sounded like a touch of paranoia. 'It would be good to come home for a bit,' he finally stated. That Richard Nixon tried to deport John Lennon in the 1970s is not beyond any reasonable doubt. John was convinced that his peace activism and lyrical barbs had made him a government target."

ㅡ From the book "Standing In The Wings" by Joe Flannery.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi Matea, hello! here are my book recs from this year: The Bottoms by Joe R. Lansdale, The Fisherman by John Langan and Wise Blood by Flannery O'Connor

hello, petra! put them all on my to-read list. the fisherman in particular has piqued my interest! thank you! <3

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

really long essay under cut

Title: Love and Violence in Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People” and “The Lame Shall Enter First”

“From the days of John the Baptist until now, the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and the violent bear it away.” —Matthew 11:12

What Happens in Milledgeville

Inside a quiet farmhouse in Milledgeville, Georgia, Flannery O’Connor’s modest bedroom sits suspended in amber like a mid-twentieth century fossil.

Unlike the rest of the sparse, picture-perfect home, this cramped living space is adorned with an array of eclectic mementos and oddly-arranged furniture that helps visitors to visualize the personal side of the author’s brief, monastic life. Describing his own trip to the Andalusia property a decade prior, Dr. Paul Reich writes that “for students of O’Connor’s work […] this empty, lonely place is transformed by the context of the author’s narratives; as each part of the farm resonates with O’Connor’s readers, they draw fresh understanding of the literature” (417). On the topic of emptiness, there is indeed something absent from the tables and shelves that line the museum: books. During the tour that I took, a docent remarked that O’Connor’s collections were moved into the nearby Georgia State College archives for preservation purposes—ironically, and despite her contrarian disregard for music, there are now more vinyl records in the house than there is literature. Even so, a few sturdier selections remain in O’Connor’s bedroom for accuracy’s sake, including an especially flirty pink-and-black hardcover boasting the eccentric title “Love and Violence.”

Although a quick Google search reveals that Love and Violence (1954) is actually a collection of Catholic philosophical essays rather than a saucy work of romance fiction, it initially stood out to me because of its potential relationship to O’Connor’s oeuvre. During my visit to Andalusia as part of a field study centered around Southern literature, we were tasked with, in Reich’s words, “avoid[ing] the traps of literary tourism” as we considered the connection between author, place, and text (418). Although O’Connor’s farm is certainly not sensational tourist-bait in the way that William Faulkner’s Mississippi estate or the historic Mercer-Williams house might be, “uncritical sentimentalism” or “hero worship” were still explicitly frowned upon during our visits to each site (Reich and Russell 419). We were instead urged to think about “the author’s house, the guide’s rhetoric, and the region’s self-presentation […] as an extension of textual interpretation” in order to “more deeply understand the reach of close reading as a mode of understanding not just the texts [we] read but the world in which [we] live” (Reich and Russell 419).

As a former student from my institution put it, this room “wasn’t just a space, it was a home. It was where she grew up and became the person that would write all of the things [we’d] been reading and re-reading” (Reich and Russell 428). With all of this in mind, the following research serves as the natural extension of that original pedagogical goal.

As I laid in my hotel room sometime after leaving Milledgeville, however, I kept thinking about Love and Violence. Frantically, and perhaps under the influence of one too many dinnertime drinks, I pulled out my phone and found an original copy of the 1954 anthology on eBay for a whopping $6 plus shipping.

Regardless of the contents of that book, I was obviously intrigued by the concept of love and violence more generally, and I wanted to better understand how these ideas manifested in O’Connor’s short stories as I continued my research. As our other readings from class have shown, love and violence are both prevalent topics across the full gamut of Southern Gothic literature, speaking to this paper’s generic relevance: In Faulkner’s Light in August (1932), Joe Christmas and Joanna Burden’s torrid affair comes to a deadly climax after pages of conflicting romantic messaging. In John Berendt’s Gothic-adjacent Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994), the death of Danny Hansford at the hands of his lover Jim Williams serves as the driving force of the narrative, while in the haunting Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir (2020), author Natasha Trethewey’s mother endures years of prolonged abuse from her own violent husband. Yet, out of all the texts that we’ve read, O’Connor’s stories evidence a particular, recurrent interest in love and violence—something perhaps spawned by her personal studies of religious philosophy.

Describing her own work in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, O’Connor writes that “violence is strangely capable of returning [her] characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace,” and that “violence is a force which can be used for good or evil” (144, 146). As David Griffith writes, “her stories reveal the hidden evil residing in the human heart, the pursuit of good that masks a secret pride.” While much of the existing scholarship characterizes the violence within O’Connor’s fiction as an embodiment of the literary convention of the grotesque, there has been little meaningful discussion of intertwined instances of love and violence in her stories.

To mediate that gap is knowledge, the following analysis will focus on this dual thematic notion within “Good Country People” (1955) and “The Lame Shall Enter First” (1965) while considering how O’Connor’s understanding of religion tracks onto those two main motifs, especially in the context of secondary themes of gender and family. First, I look at romantic or sexual love and violence in “Good Country People,” and then familial love and violence in “The Lame Shall Enter First,” arguing that O’Connor’s portrayals of love and violence showcase a subtle, albeit distinct, Catholic influence that cannot be explained through the lens of regionalism alone. As I further deduce, this Catholic influence has made an impression upon the Southern Gothic style more broadly. While O’Connor is frequently touted as a foundational author of Southern Gothic fiction, the relative dominance of Protestantism in the American South might otherwise mask the presence of certain Catholic philosophical themes within its literature. Therefore, this study is an important exploration of the author’s legacy beyond the vague umbrellas of both “Southern” and “Christian.”

The Catholic Novelist

Catholicism was clearly an important part of O’Connor’s personal and professional life, and her classification as a “Christian novelist” is a topic that appears many times throughout her essays—as she once famously stated, “because I am a Catholic, I cannot afford to be less than an artist” (Mystery 184). In a prayer book from her days at the Iowa Writers Workshop, a younger O’Connor likewise laments, “don’t let me ever think, dear God, that I was anything but the instrument for Your story,” speaking to Catholicism’s influence on her writing (Robinson).

Still, both modern and twentieth century critics have pointed out that many of O’Connor’s short stories are not explicitly religious, and that the examples which do have an obvious spiritual undercurrent never have an uplifting “Christian” message. As Joseph O’Neil notes, “O’Connor was dismissive of any pressure, whether of religious or secular origin, for more ‘positive’ fiction. She saw no contradiction between her faith and her art.” In the author’s own sardonic words, “the demand for positive literature, which we hear so frequently […] comes about possibly from weak faith and possibly also from [a] general inability to read” (Mystery 238). Rather, O’Connor states that “every serious novelist is trying to portray reality as it manifests itself in our concrete, sensual life” and that if she “had to say what a ‘Catholic novel’ is, [she] could only say that it is one that represents reality adequately as we see it manifested in this world of things and human relationships” (Mystery 214).

According to O’Neil, O’Connor usually described herself as a “thirteenth century” Catholic, not a Christian, and she was a dedicated scholar of religious philosophers like the Rev. Dr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Simone Weil, and Soren Kierkegaard. To put that “century” quip in context, John Morreal states that before the 1500s, the “compartmentalized concept” of religion in which spiritual beliefs were separate from secular life was nonexistent, and that early Catholic spirituality was deeply and fully intertwined with daily life (12). As O’Connor writes, “you may ask, why not simply call this literature Christian? Unfortunately, the word Christian is no longer reliable. It has come to mean anyone with a golden heart. And a golden heart would be a positive interference in the writing of fiction�� (Mystery 242).

Fittingly, this fascination with the distinction between old and new world Christianity can be seen within her short stories; O’Connor’s settings are almost always “agrarian, static, unscientific, [and] largely insulated from modern modes of information and movement. […] The dramatic premises are almost premodern, very easily concerned with religious visionaries or with the arrival, into an unchanging locale, of a stranger” (O’Neil). Branching off of the idea of religion being intertwined with reality, religiosity is thus deeply ingrained in her narratives: there is no heavy-handed religious symbolism separate from, or applied on top of, the story itself, as is perhaps the case with Joe “Jesus” Christmas in Faulkner’s Light in August. Indeed, as O’Neil continues, “with O’Connor, there never seems to be space between the words and their creator’s sensibility. You almost never catch a whiff of authorial self-consciousness.” Speaking to her own intent behind the portrayals of violence in her story “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” O’Connor writes: “I don’t want to equate the Misfit with the devil […] however unlikely this may seem, the old lady’s gesture, like the mustard-seed, will grow to be a great crow-filled tree in the Misfit’s heart” (Mystery 145).

Romance, Gender, and Abuse

Now that a brief history of O’Connor’s religious background has been established, it is important to critically consider the intent behind her portrayals of love and violence because it is a theme so clearly dominant in her narratives. Yet, if it is the duty of the novelist to, in the words of fellow Southern Gothic author Anne Rice, “follow their most intense obsessions mercilessly,” where does such an obsession come from?

As O’Neil argues, O’Connor’s writing is an extension of an “ancient, artistically wholesome tradition of misanthropy.” Perhaps due to a combination of illness and maternal oversight, O’Connor’s isolated life at Andalusia warranted her few romantic attachments. Erik Langkjaer, a college textbook salesman who might have served as loose inspiration for the antagonist in “Good Country People,” wrote of his brief kiss with O’Connor after making multiple visits to the household: “she had no real muscle tension in her mouth, a result being that my own lips touched her teeth rather than lips, and this gave me an unhappy feeling of a sort of memento mori,” noting brutally that “I had a feeling of kissing a skeleton” (Williams). Unsurprisingly, displays of romantic or sexual love in O’Connor’s short stories are similarly limited, and are usually brutally abusive or generally “toxic” in some way.

In the aforementioned “Good Country People,” the motif of romantic or sexual love and violence appears most prominently in the relationship between Joy-Hulga Hopewell and Manley Pointer. After meeting Pointer, Hopewell begins to scheme about seducing him after lying about her age, believing that his identity as a Christian makes him naive and easily manipulatable. O’Connor writes: “During the night she had imagined that she seduced him” and that after kissing him for the first time, “her mind, clear and detached and ironic anyway, was regarding him from a great distance, with amusement but with pity. She had never been kissed before and she was pleased to discover that it was an unexceptional experience and all a matter of the mind’s control” (648, 651). In these passages, Hopewell is characterized as aggressive and calculating in the exchange with the younger, seemingly innocent boy. The fact that she says she sees Pointer “from a great distance” and with “amusement” and “pity” positions her in a predatory role, as she believes she is taking advantage of somebody beneath her intellectually.

The passive violence of Hopewell’s behavior soon backfires, however, after Pointer repeatedly demands “you got to say you love me” (O’Connor 656). After Pointer repeats the phrase multiple times, Hopewell is unable to meet this demand for “love” and resorts to a stilted, overly intellectual answer. Following the awkward exchange, Hopewell quickly switches from victimizer to victimized when she sees Pointer’s collection of obscene objects inside the Bible and is promptly robbed of her prosthetic leg. Pointer’s final assertion to Hopewell that “‘you ain’t so smart’” establishes both a literal and physical dominance over her in the end (O’Connor 663).

Through this mutually violent relationship, O’Connor showcases the irony of Hopewell’s arrogance and entitlement on the basis of her rejection of religion. According to Virginia Goldner et al., however, “abusive relationships exemplify, in extremis, the stereotypical gender arrangements that structure intimacy between men and women generally” (343). As Lea Melandri likewise confirms, “male dominance and female subservience are established by society through a binary and oppositional understanding of sex and gender” (1). In Hopewell’s case, her identity as a highly-educated, atheistic, and disabled woman makes her an atypical female character compared to the idealized Southern Belle archetype; regarding the second characteristic, Pointer says “‘that’s very unusual for a girl’” (O’Connor 651). While this perhaps awards her with a certain level of freedom inaccessible to others her age, none of it protects her from the eventual violation at the hands of her partner.

As Goldner likewise found in her case study, a “rebellion against oppressive gender codes” within the context of abusive relationships “creates a belief that the relationship is a unique haven from the outside world,” evident in the fantastical way in which Hopewell fantasizes about the seduction (360). Indeed, her repeated rebellion against both her mother and broader societal norms is a driving factor in her initial attraction to the idea of seducing Pointer: As she lays in bed prior to their date, she imagines “dialogues for them that were insane on the surface but that reached below to depths that no Bible salesman would be aware of,” again highlighting her obsession with “corrupting” the man she believes to be an innocent Christian (O’Connor 645).

In The Habit of Being, O’Connor uses the ironic phrase “the violence of love” to describe the kind of “self-sacrifice” that embodies the love characteristic of Christ’s non-violence—as Susan Srigley states, “this can be construed as violence against the self, or a ‘death’ of the self, for the sake of others, and ultimately, for the sake of the Kingdom of God” (35). According to Srigley,

the ‘violence of love’ is the […] restraint of one’s own desires. In this sense, love can entail a felt ‘violence’ insofar as it must actively overcome the desires and impulses of the self for the sake of another. O’Connor sees love as an active response to God and other human beings […] and the order of that love means that the self is not the centre of existence. (36)

In the case of both Hopewell and Pointer, they are thereby “loveless” not in their displays of maliciousness toward each other, but in their total inability to decenter themselves in the context of their romantic interactions. Both Hopewell’s mental gymnastics and Pointer’s physical abuse work in this same way: Just as Pointer exclaims that “I been believing in nothing ever since I was born,” O’Connor notes that Hopewell is “spiritually as well as physically crippled. She believes in nothing but her own belief in nothing, and we perceive that there is a wooden part of her soul that corresponds to her wooden leg” (663, Mystery 128). In the religious sense, this selfishness makes them equally unable to actualize the “violent love” necessary to understand God’s grace, speaking to the author’s intent in undermining the antagonist’s cynical authority.

Family, Neglect, and Suicide

Next, in “The Lame Shall Enter First,” the themes of familial love and violence are most evident in the father-son relationship between Sheppard and Norton, as well as the quasi-son figure of Rufus Johnson. Norton is extremely distraught over his mother’s death, although his grief annoys his rational, atheistic father Sheppard who believes that it “was not a normal grief. It was all part of his selfishness. She had been dead for over a year and a child’s grief should not last so long” (O’Connor 1021). O’Connor continues describing Sheppard’s response to his depressed son: “‘Don’t you think I miss her at all? I do, but I’m not sitting around moping. I’m busy helping other people. When do you see me just sitting around thinking about my troubles?’” (1022). From these interactions, it’s clear that Sheppard’s emotional neglect of Norton stems from a misplaced sense of secular altruism: By turning to his new pet-project Johnson, a troubled yet highly intelligent boy who Sheppard believes he can reform through proper education and attention, the father “wanted to give the boy something to reach for besides his neighbor’s goods” in order to feel as if he was doing something right in the world (O’Connor 1030).

When Sheppard’s attempts at reform fail, Johnson continues to uphold both his skewed Christian worldview and tendencies for criminality and thievery while Norton’s needs quickly take the backburner. After Norton becomes obsessed with looking into the sky through Johnson’s telescope, the father states “I don’t want to hear about Norton,” and that regarding his reformation of the foster child, “my resolve isn’t shaken […] I’m going to save you” (O’Connor 1080, 1082). By the end of the story, Johnson is arrested, exclaiming that “I lie and steal because I’m good at it!” and Norton hangs himself in order to join his dead mother in heaven, ultimately highlighting Sheppard’s inability to connect with either of his “sons” (O’Connor 1097).

Utilizing the contrast between Johnson and Norton, O’Connor indicates the futility of Sheppard’s attempts at secular reformation. By putting all of his attention toward Johnson, he deprives his own son of love and affection, leading Norton to find refuge in fantasy and death. The indirect violence of Sheppard’s ignorance toward Norton is consequently the exact kind of selfishness he decries—a behavior that stands in direct contrast to the definition of violent love that O’Connor provides in The Habit of Being. Likewise, as Alicia Matheny Beeson argues, “in his eagerness to practice what he sees as good charitable work to inflate his own sense of self, Sheppard disregards what Johnson actually wants or needs” (50). While Sheppard believes that altruism is synonymous with both love and goodness, his inability to connect with either his surrogate or natural offspring evidences a tragic failure to harness a “love that serves the other, and as such, requires a sacrifice of the self in the form of spiritual discipline” (Srigley 36).

Like both Hopewell and Pointer, Sheppard is spiritually dead not only due to his refusal to accept God—as is clear in his response to Johnson’s vague religiosity with “rubbish! […] We’re living in the space age”—but in his overall narcissism and inflated sense of grandiosity regarding his influence on Johnson (1029). Beyond his blanket rejection of religion, Sheppard’s self-centered idea of what constitutes appropriate emotional behavior in the case of Norton’s grief makes him unable to access the kind of sacrificial love that O’Connor deems to be truly redemptive.

Ironically, Norton’s recurrent obsession with his deceased mother is most similar to the kind of violent love described in the previous paragraphs; of course, his death is a self-sacrifice in the literal definition of the phrase, but the final act of suicide is also a symbolic expression of his devotion to her. As Srigley says,

the violence of love is a sacrifice borne by the self […] a movement of the spirit towards what is truly life giving, perceived when the self is no longer the center of one’s existence. It is not the modern or popular conception of love—commonly tied to the gratification of one’s desires rather than the disciplined ordering of them—but it is at the heart of O’Connor’s religious vision. (37)

While Sheppard sees his son’s persistent ideation of his mother as a form of negative self indulgence, it is actually Sheppard’s thinly veiled attempts at goodwill that are genuinely conceited. Describing his father’s character, Johnson exclaims to Norton, “‘Listen here […] I don’t care if he’s good or not. He ain’t right!’” (O’Connor 1037). The emphasis on “right” speaks to the latent nature of Sheppard’s intentions, which are, in Johnson’s mind, dubious at best. It is a kind of passive violence not unlike the inner scheming of Hopewell, and certainly bears a similar unfortunate end. By contrast, Norton’s wholehearted, innocent dedication to his mother’s memory is evident in Sheppard’s final mental image of his son: “the little boy’s face appeared to him transformed; the image of his salvation; all light” (O’Connor 1100).

A Southern Tradition

Speaking to the effect of O’Connor’s religious vision, Farrell O’Gorman claims that “the recurrent role of Catholicism in [the] Gothic tradition” stems from the fact it is a “religion without a country,” therefore threatening to “break down borders separating American citizens” (1). In the context of a Southern Gothic literary tradition largely concerned with questions of borders, isolation, and alienation, it seems fitting that one of the foundational authors of the genre features Catholic theology so prevalently throughout her stories. A final notion worth tackling when it comes to the topics of love, violence, and religion in O’Connor’s work is thus how this Catholic influence has affected or impressed upon the Southern Gothic style more broadly. In the essay “The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South,” O’Connor writes that “the two circumstances that have given character to my own writing have been those of being Southern and being Catholic,” and that “this is considered by many to be an unlikely combination, but I have found it to be a most likely one” (248).

Indeed, the “outsider” position of the Catholic within the Protestant-dominated Southern United States perhaps gives the author a unique viewpoint, one that aligns more with the “backwoods prophets and shouting fundamentalists than […] with those politer elements […] for whom religion has become a department of sociology or culture or personality development” (Mystery 261). As this essay has so far considered, religious philosophy has clearly informed the portrayal of romantic and familial love and violence in O’Connor’s short stories, highlighting the comparative desirable values of faith, self-sacrifice, and grace that are lacking in mainstream culture.

In the previously referenced article, Reich ends the discussion of the field study by stating that “our experiences both in and out of the classroom all worked to form a more nuanced reading of the South’s municipalities and extended that multiplicity to our understanding of the classroom and its boundaries” (431). Similarly, my personal reflection on the trip involved a greater appreciation for the importance of experiential learning beyond the traditional academic context; if I had not seen that interesting looking book on the shelf inside that room at Andalusia, for instance, I probably would not have had reason to consider any of the ideas explored in this essay. To be able to make those connections was valuable, and to consider the intersection between literature and biography was something I had done little of in past assignments.

Ironically, however, O’Connor writes that “a work of art exists without its author from the moment the words are on paper, and the more complete the work, the less important it is who wrote it or why. If you’re studying literature, the intentions of the writer have to be found in the work itself, and not in his life” (Mystery 160). It may seem pointless, then, to attempt to consider questions of intent or religious philosophy from a biographical perspective. Yet, as O’Neil so aptly puts it: “nonetheless, a spiritual drama is playing out. Only it is not the one put forward by the self-explaining author, in which she figures as an onlooker occupying the high ground of piety. On the contrary, Flannery O’Connor’s criticism reveals her as scarily belonging to the low world she evokes. She was touched by evil and no doubt knew it. That is what makes her so wickedly good.”

FIN.

Works Cited

Beeson, Alicia Matheny. “The Failure of Compassion: Problematic Redemption and the Need for Praxis in ‘The Lame Shall Enter First’ and ‘The Comforts of Home.’” Reconsidering Flannery O’Connor, University Press of Mississippi, 2020, p. 50.

Goldner, Virginia et al. “Love and Violence: Gender Paradoxes in Volatile Attachments.” Family Process, vol. 29, no. 4, Wiley-Blackwell, 1990, pp. 343-364.

Griffith, David. A Good War is Hard to Find. New York: Soft Skull Press, 2006.

Melandri, Lea. Love and Violence: The Vexatious Factors of Civilization. SUNY Press, 2020.

Morreall, John and Sonn, Tamara. “Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions.” 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 12-17.

O’Connor, Flannery. Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. eBook.

O’Connor, Flannery. Flannery O’Connor: The Complete Stories. HarperPerennial Classics, 2015. eBook.

O’Connor, Flannery. The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988.

O’Gorman, Farrell. Catholicism and American Borders in the Gothic Literary Imagination. University of Notre Dame Press, 2017.

O’Neil, Joseph. “Touched by Evil.” The Atlantic. 2009.

Reich, Paul and Russell, Emily. “Taking the Text on a Road Trip: Conducting a Literary Field Study.” Pedagogy, vol. 14, no. 3, Duke University Press, 2014, pp. 417-433.

Rice, Anne. “Forward.” The Metamorphosis and Other Stories, 1995.

Robinson, Marilynne. “The Believer: Flannery O’Connor’s Prayer Journal.” The New York Times, 15 November 2023.

Srigley, Susan. “The Violence of Love: Reflections on Self-Sacrifice through Flannery O’Connor and René Girard.” Religion & Literature, vol. 39, no. 3, The University of Notre Dame, 2007, pp. 31-45.

The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. “Matthew 11:12.” Bible Gateway, 2023.

Williams, Joy. “Stranger Than Paradise: ‘A Life of Flannery O’Connor by Brad Gooch.” The New York Times. 26 February 2009.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“These days it is widely acknowledged that there are male and female elements in all forms of human behaviours. But in those days a northern sexual spade was most decidedly not a shovel, and for those of us who began to question our sexuality it was a particularly startling experience. You might have been beaten, you might be jailed; you might lose your job or have to lead a double life. One could fall foul of a blackmailer or even be sent to a mental asylum. In fact, a friend of mine voluntarily committed himself to spend some time in Rainhill Mental Hospital in a forlorn attempt to rid himself of his homosexual inclinations. He was given heterosexual pornography in an attempt to stimulate his seemingly dormant heterosexuality and drug aversion therapy when shown homosexual pornography. Naturally enough, it was all a complete waste of time.”

Standing in the Wings: The Beatles, Brian Epstein and Me by Joe Flannery

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We never threw out our ashes at Gardner Road, but would bank up the fires on the cold winter's nights before and after gigs. This cosy netherworld began to attract young musicians and within a short space of time the apartment became a real haven for musos. It became open house. [...]

The Beatles did not appear immediately, but after learning from the eminent Bob Wooler that my address was behind the recently opened Granada Bowling Alley on Green Lane, they soon began turning up for tea, toast, and advice in between games of ten-pin bowling."

-

"By the Christmas of 1961 Kenny and I had become so busy by day and night that we employed a housekeeper, the wonderful and resilient Anne, and Anne's catering and attention to detail - not to mention her beautiful young daughter, Girda - far outstripped her rather caustic tongue. She was very welcoming to young band members who mostly saw beyond her authoritarian facade. [...]

Everyone was treated alike by Anne. She was totally unaffected by egos, stardom and petulance. She was like a surrogate mother to the groups and would chastise them if they were late or hadn't ironed their stage clothes. There would be occasions when I would return home to find three or four young musicians semi-clothed, only to find that Anne had got them to strip off their shirts because they needed 'a good ironing'.

She had me worried at times, but she knew that even though I was earning my crust via retail, my heart was totally with the music, and so she acted as both their conscience and my guardian angel, constantly reminding them of their duties to me as professionals. Anne could be very caustic with my brother and was at times highly critical of him, disliking his inflated ego while appreciating his obvious talent. She would tell him to his face that I deserved better from him, that his band deserved better too, but Lee would laugh it all off - unlike the attentive John Lennon and Paul McCartney who seemed to pay a great deal of attention to Anne's salutary remarks."

-

"As stated previously, I think Girda was a big attraction for Paul, but they all loved the ambience, particularly John Lennon who would often fall asleep in the chair in front of the fire after endlessly doodling on scraps of paper. I got the impression that there was little at home to inspire him and that he preferred the warmth (in more ways than one) of Gardner Road. John would generally sleep through until late in the morning, when he would be awoken by the arriving Anne pulling out the ashes from the extinguished fire and lighting the new blaze with the assistance of his doodle-ridden scraps of paper."

-

"By 1962, of course, Brian Epstein had the Beatles under his control; however, that control was actually shared to a great degree, at least while at Gardner Road, with yours truly and my housekeeper. It was Anne, as she reminded me shortly before her death, who suggested to Brian that the Beatles should be put into the best quality suits that he could afford. It was also Anne who ridiculed Brian one evening for turning up in an all-leather outfit... it was never seen again.

Although pop history loves to dwell on myth, often attributing seminal moments to specific characters, suggesting genius and inspired thought and inspirational moments, the real flashes of history actually revolve around stinging remarks, little asides and offhand suggestions. A great deal of popular music history finds this a little too complicated and rather difficult to record, for it appears better to suggest gleams of impulse rather than ridicule, satire and irony. But Anne's place in the Beatles story is a valid one. It was she who was a catalyst for all visitors to Gardner Road; it was she who fed them, pressed their shirts, lampooned them and deflated their egos."

Standing in the Wings, by Joe Flannery (with Mike Brocken)

#god but they really were seeking out mothering all over the city#absolute whores#really odd to be reading a beatles book#and have anyone give any credit to any woman in their lives#as affecting things at all#but I really like that final paragraph#little asides and offhand suggestions#really are what history is made of#and it's what you so often miss#if you let men write history#the beatles#joe flannery#standing in the wings#beatles books

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Burke’s Law - List of Guest Stars

The Special Guest Stars of “Burke’s Law” read like a Who’s Who list of Hollywood of the era. Many of the appearances, however, were no more than one scene cameos. This is as complete a list ever compiled of all those who even made the briefest of appearances on the series.

Beverly Adams, Nick Adams, Stanley Adams, Eddie Albert, Mabel Albertson, Lola Albright, Elizabeth Allen, June Allyson, Don Ameche, Michael Ansara, Army Archerd, Phil Arnold, Mary Astor, Frankie Avalon, Hy Averback, Jim Backus, Betty Barry, Susan Bay, Ed Begley, William Bendix, Joan Bennett, Edgar Bergen, Shelley Berman, Herschel Bernardi, Ken Berry, Lyle Bettger, Robert Bice, Theodore Bikel, Janet Blair, Madge Blake, Joan Blondell, Ann Blyth, Carl Boehm, Peter Bourne, Rosemarie Bowe, Eddie Bracken, Steve Brodie, Jan Brooks, Dorian Brown, Bobby Buntrock, Edd Byrnes, Corinne Calvet, Rory Calhoun, Pepe Callahan, Rod Cameron, Macdonald Carey, Hoagy Carmichael, Richard Carlson, Jack Carter, Steve Carruthers, Marianna Case, Seymour Cassel, John Cassavetes, Tom Cassidy, Joan Caulfield, Barrie Chase, Eduardo Ciannelli, Dane Clark, Dick Clark, Steve Cochran, Hans Conried, Jackie Coogan, Gladys Cooper, Henry Corden, Wendell Corey, Hazel Court, Wally Cox, Jeanne Crain, Susanne Cramer, Les Crane, Broderick Crawford, Suzanne Cupito, Arlene Dahl, Vic Dana, Jane Darwell, Sammy Davis Jr., Linda Darnell, Dennis Day, Laraine Day, Yvonne DeCarlo, Gloria De Haven, William Demarest, Andy Devine, Richard Devon, Billy De Wolfe, Don Diamond, Diana Dors, Joanne Dru, Paul Dubov, Howard Duff, Dan Duryea, Robert Easton, Barbara Eden, John Ericson, Leif Erickson, Tom Ewell, Nanette Fabray, Felicia Farr, Sharon Farrell, Herbie Faye, Fritz Feld, Susan Flannery, James Flavin, Rhonda Fleming, Nina Foch, Steve Forrest, Linda Foster, Byron Foulger, Eddie Foy Jr., Anne Francis, David Fresco, Annette Funicello, Eva Gabor, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Reginald Gardiner, Nancy Gates, Lisa Gaye, Sandra Giles, Mark Goddard, Thomas Gomez, Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez, Sandra Gould, Wilton Graff, Gloria Grahame, Shelby Grant, Jane Greer, Virginia Grey, Tammy Grimes, Richard Hale, Jack Haley, George Hamilton, Ann Harding, Joy Harmon, Phil Harris, Stacy Harris, Dee Hartford, June Havoc, Jill Haworth, Richard Haydn, Louis Hayward, Hugh Hefner, Anne Helm, Percy Helton, Irene Hervey, Joe Higgins, Marianna Hill, Bern Hoffman, Jonathan Hole, Celeste Holm, Charlene Holt, Oscar Homolka, Barbara Horne, Edward Everett Horton, Breena Howard, Rodolfo Hoyos Jr., Arthur Hunnicutt, Tab Hunter, Joan Huntington, Josephine Hutchinson, Betty Hutton, Gunilla Hutton, Martha Hyer, Diana Hyland, Marty Ingels, John Ireland, Mako Iwamatsu, Joyce Jameson, Glynis Johns, I. Stanford Jolley, Carolyn Jones, Dean Jones, Spike Jones, Victor Jory, Jackie Joseph, Stubby Kaye, Monica Keating, Buster Keaton, Cecil Kellaway, Claire Kelly, Patsy Kelly, Kathy Kersh, Eartha Kitt, Nancy Kovack, Fred Krone, Lou Krugman, Frankie Laine, Fernando Lamas, Dorothy Lamour, Elsa Lanchester, Abbe Lane, Charles Lane, Lauren Lane, Harry Lauter, Norman Leavitt, Gypsy Rose Lee, Ruta Lee, Teri Lee, Peter Leeds, Margaret Leighton, Sheldon Leonard, Art Lewis, Buddy Lewis, Dave Loring, Joanne Ludden, Ida Lupino, Tina Louise, Paul Lynde, Diana Lynn, James MacArthur, Gisele MacKenzie, Diane McBain, Kevin McCarthy, Bill McClean, Stephen McNally, Elizabeth MacRae, Jayne Mansfield, Hal March, Shary Marshall, Dewey Martin, Marlyn Mason, Hedley Mattingly, Marilyn Maxwell, Virginia Mayo, Patricia Medina, Troy Melton, Burgess Meredith, Una Merkel, Dina Merrill, Torben Meyer, Barbara Michaels, Robert Middleton, Vera Miles, Sal Mineo, Mary Ann Mobley, Alan Mowbray, Ricardo Montalbán, Elizabeth Montgomery, Ralph Moody, Alvy Moore, Terry Moore, Agnes Moorehead, Anne Morell, Rita Moreno, Byron Morrow, Jan Murray, Ken Murray, George Nader, J. Carrol Naish, Bek Nelson, Gene Nelson, David Niven, Chris Noel, Kathleen Nolan, Sheree North, Louis Nye, Arthur O'Connell, Quinn O'Hara, Susan Oliver, Debra Paget, Janis Paige, Nestor Paiva, Luciana Paluzzi, Julie Parrish, Fess Parker, Suzy Parker, Bert Parks, Harvey Parry, Hank Patterson, Joan Patrick, Nehemiah Persoff, Walter Pidgeon, Zasu Pitts, Edward Platt, Juliet Prowse, Eddie Quillan, Louis Quinn, Basil Rathbone, Aldo Ray, Martha Raye, Gene Raymond, Peggy Rea, Philip Reed, Carl Reiner, Stafford Repp, Paul Rhone, Paul Richards, Don Rickles, Will Rogers Jr., Ruth Roman, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Gena Rowlands, Charlie Ruggles, Janice Rule, Soupy Sales, Hugh Sanders, Tura Satana, Telly Savalas, John Saxon, Lizabeth Scott, Lisa Seagram, Pilar Seurat, William Shatner, Karen Sharpe, James Shigeta, Nina Shipman, Susan Silo, Johnny Silver, Nancy Sinatra, The Smothers Brothers, Joanie Sommers, Joan Staley, Jan Sterling, Elaine Stewart, Jill St. John, Dean Stockwell, Gale Storm, Susan Strasberg, Inger Stratton, Amzie Strickland, Gil Stuart, Grady Sutton, Kay Sutton, Gloria Swanson, Russ Tamblyn. Don Taylor, Dub Taylor, Vaughn Taylor, Irene Tedrow, Terry-Thomas, Ginny Tiu, Dan Tobin, Forrest Tucker, Tom Tully, Jim Turley, Lurene Tuttle, Ann Tyrrell, Miyoshi Umeki, Mamie van Doren, Deborah Walley, Sandra Warner, David Wayne, Ray Weaver, Lennie Weinrib, Dawn Wells, Delores Wells, Rebecca Welles, Jack Weston, David White, James Whitmore, Michael Wilding, Annazette Williams, Dave Willock, Chill Wills, Marie Wilson, Nancy Wilson, Sandra Wirth, Ed Wynn, Keenan Wynn, Dana Wynter, Celeste Yarnall, Francine York.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 4.25

Beer Birthdays

Al Levy (1860)

Cassio Piccolo (1960)

Stephen Beaumont (1964)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Batman; comic book character (1940)

Ella Fitzgerald; jazz singer (1917)

Jason Lee; actor (1970)

Meadowlark Lemon; Harlem Globetroters basketball player (1932)

Edward R. Murrow; broadcast journalist (1908)

Famous Birthdays

Karel Appel; Dutch painter (1921)

Hank Azaria; actor (1964)

Andy Bell; pop singer (1964)

Earl Bostic; saxophonist (1913)

William J. Brennan Jr.; U.S. Supreme Court justice (1906)

Joe Buck; sportscaster (1969)

Ron Clements; animator (1953)

Oliver Cromwell; English politician (1599)

Willis "Gator" Jackson; saxophonnist (1932)

Albert King; blues singer (1923)

Jerry Leiber; pop songwriter (1933)

Guglielmo Marconi; physicist, radio inventor (1874)

Paul Mazursky; film director (1930)

Flannery O'Connor; writer (1925)

Al Pacino; actor (1940)

Eugene “Gene Gene the Dancing Machine” Patton; stagehand, dancer (1932)

Wolfgang Pauli; physicist (1900)

Talia Shire; actor (1946)

John Frank Stevens; Panama Canal engineer (1853)

Renee Zellweger; actor (1969)

1 note

·

View note