#its weird to think about how many different versions of me exist across the spectrum from a lifetime of experience. you know??

Text

🦋

#occassionally i cannot help but wonder what like. versions of me exist out in ppls heads lmao.#from like the random groups of ppl ive gone skinny dipping w while out fucking around in waikiki#to the ppl i lied to so i could talk friends up or make them look better#to like any of the way too many ppl ive done work w lmao.#its weird to think about how many different versions of me exist across the spectrum from a lifetime of experience. you know??#anyway imma bouta chief thru about two grams of wax so stay tuned to see if i get more or less coherent as the night goes on#&also to see if i can drink this xl slurpee in under five minutes lmao.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

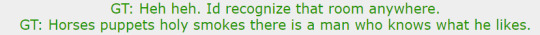

is dirk a canon horse furry?

You probably weren’t expecting an essay length answer to this question. So like let there be no doubt at all from this point onwards this is exactly the kind of content you can legitimately expect from this blog. This is who I am. I’m sorry.

Also, you’re welcome.

Yes, Dirk is a furry. And his relationship to furries shows us a lot about his parallels and similarities to one Rose Lalonde. Who is also a furry.

Let’s get into this.

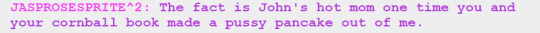

Dirk is interested in furries to some extent, and finds the aesthetic appealing on some level. I mean, look at this. I can’t even count how many pictures of muscley horse dudes there are here. The dude isn’t exactly subtle. To quote Jake…

Dirk isn’t exactly just a HORSE furry, though:

The swole bunny men help us notice something else about Dirk. As brash as he is in his introduction, bragging about his interest in sequential art that he describes as “Bordeline Pornography”, Dirk gets uncomfortable and leads the reader away when the narrative focus rests too squarely on a furry bunny dude he presumably finds attractive. He dodges, and badly at that. To Dirk, swole bunny men represent something to hide–an interest he has that he cannot honestly incorporate into his cool, stoic, Above It All Persona. Not even through the hyper-sincere irony he tells Jane about. It’s something to hide, which means that at his core it’s something that matters to him.

And hey, you know who else is very much not shy about plastering her interests where anyone can see for her own pleasure?

As plenty of people have noted recently, there’s no heterosexual explanation for this. I’d already categorize this as falling into the spectrum of anthropomorphization we talk about as Furry–if you disagree that’s fine, though I do know furries who like this kind of thing. The point is that like Dirk, Rose knows what she likes, and like Dirk, Rose likes some weird shit.

On this side of the argument, though–showing that the characters like this furry stuff through their own characterization–Dirk gets a lot more content than Rose does. But Rose’s relationship with furry is confirmed much more intensely than Dirk’s on the other side of this argument: through their relationships to their Splinters.

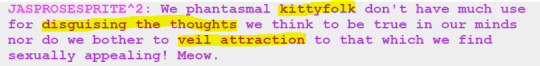

Dirk and Rose’s attitudes towards furry and their own identities lead them to distance themselves from the actual term in public. Dirk pokes fun of Avatar as “blue space furry shit” with Jake, and Rose needles John on not having his own furry alt-self, dramatically bemoaning the existence of “Cat Rose”.

In both cases, they’re happy to pretend that furry stuff doesn’t interest them at all, and part of their approach to doing so is either joking about others being interested in it or actively playing up their resentment for it. Either way, the implication they send is that they themselves are Not Interested.

This is a lie, and is to be ruthlessly exploited for comedy, which Homestuck does magnificently well.

Both Dirk and Rose are very invested in seeming Above the kind of self-indulgent identity play that Furry tends to encompass. Intense sincerity of expression bothers to them even as it appeals, because the images they want to project to the people they care about is one of aloof, self-aware, competently critical collectedness. One could say it bothers BECAUSE it appeals. Which is the exact reason Rose is so annoyed by Jasprose. Jasprose acts as Rose would without the self-awareness she uses to present only the carefully crafted persona she wants other people to see. Jasprose doesn’t think about what others think of her at all. Jasprose thinks in terms of self-indulgence.

A self-indulgence explicitly linked to their status as full-blown, unabashed Furries. Jasprose, by her very being, brings all of Rose’s hidden words and feelings to Light, not being shy at all about sharing them and indulging whatever desire is on her mind.

She mixes cat terminology with flirting, stressing her identity as someone who is a furry and loving every second of it. Davepeta even draws the distinction between her and Rose, noting that Jasprose owns who she is and acts more honestly about it.

Arquis does the same thing, but Dirk doesn’t quite resent AR for presenting a furry, happier, more honest version of himself. Dirk resents AR for entirely different reasons that I’ve already written too much about. But there are genuinely harmless ways that Arquis DOES reflect Dirk’s interest, and those are worth unpackaging. Specifically, there’s the way AR describes himself finally becoming happy.

And yeah someone could nibble with this wording and say well actually Equius likes horses so maybe its him and I actually couldn’t be less interested in trying to explain why Dirk’s character already incorporates an absolutely Furry level of enjoyment of horses so here’s his room again.

So basically Dirk and Rose are interested in furry stuff to some extent but won’t really admit it. They wouldn’t admit it to you if you asked them or anything.

I think this is really fascinating and that they share this particular nuance of characterization so completely is fantastic. Even Dirk’s double face palm and Rose’s pillow hiding feel really similar to me in the sentiment of mortified frustration it gets across.And all this really stresses their similarities and makes Roxy’s line emphasizing how similar Rose and Dirk are hit home all the harder. I wanted to ramble about that for a while. God I love these kids what was I talking about again?

Oh yeah furries. So Rose and Dirk are both furries but neither of them would CALL themselves furries in public.

Yet. The thing is, this girl exists:

Give Jade like, one birthday party where she decides she wants everyone to have a furry party and draw up fursonas together, and we’re good to go. There’s pretty much no circumstances under which I doubt Jade’s power to get all her friends to stop hiding an interest they ALL KNOW DEEP DOWN they share with her but keep pushing away out of a dumb point of pride.

It’ll be great I promise someone write this fic ok thanks in advance. Anyway yeah give Jade like a year after they get to Earth C and she’ll get them all on the same page. By which I mean all, not just Dirk and Rose.

Jane’s actually the only main character who hasn’t expressed any interest in furries at any point in the story to my memory, and she’s already been willing to play around with trollsonas. Which means at some point in the context of eternity these kids are going to get the hell over themselves and draw some fursonas. And if they don’t, Jade will make sure they will. So yeah. Every human kid in Homestuck is a furry. Also every living troll, and Callie. Probably all their subjects too frankly.

Welcome to Homestuck canon!

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Countercinema” and “I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing”

Can an argument be made for the existence of a female gaze, or a “specific, identifiable” female aesthetic of film? Is I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing successful at achieving a truly feminist vision on film?

Introduction

Marilyn Fabe’s article, “Feminism and Film Form: Patricia Rozema’s I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing,” circles back to the very first reading in the course, which was Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” I find this very interesting that the final article talks directly about the first article we read. Fabe credits Mulvey with the idea that “most mainstream films assume a male spectator and play to male pleasure by visually objectifying and eroticizing the women on the screen.” In response, she “raises the issue of how women filmmakers can create alternative conventions to liberate cinema from male-centered practices of representation.” While an argument can be made for the existence of a female gaze, I don’t think this is what Mulvey and Rozema have in mind. They don’t cite the existence of a specific, identifiable, female aesthetic of film. Instead, they propose feminist approaches to making films, which is referred to as “counter cinema.” Fabe analyzes Mermaids as an example of counter-cinema. Her analysis can also be applied to other films we’ve studied, using some of the same concepts she explores.

“Plot synopsis”

In her article, Fabe reviews the history of feminist film criticism. She explains that “women on the screen are often nothing more than cultural stereotypes.” And these stereotypes are usually negative and “reinforce the idea of women’s inferiority,” she says. She then describes cinema-specific approaches to women in film. According to Fabe, feminist film theorists were able to “demonstrate how film’s unique means of representation and specific appeal help construct or naturalize denigrating ways of looking at women.” The film Dance, Girl, Dance features many of the conventional film narratives that feminist film theorists have criticized. The characters played by Lucille Ball and Maureen O’Hara represent a common cultural stereotype of woman as the burlesque dancer. Ball plays a sort of “femme fatale,” like the stereotypical “blonde bombshell” type. A recurring scene is when she goes behind a tree and pretends to be taking her clothes off; it’s a teaser for the audience, which is mostly male.

In contrast, Fabe points out how the plot in Mermaids “focuses on the concerns and desires of its female protagonist,” Polly. Instead of the usual male hero, Polly is a very unlikely heroine. Fabe says that “if the film is read as a fairy tale, then “Polly needs no prince to redeem her. The happy ending comes when she learns to value herself and discovers kindred spirits with whom to share her work.” The character of Polly is quite interesting and quirky. I don’t want to label her or make assumptions, but she seems to have some sort of “difference,” like Autism Spectrum Disorder (of which I am very familiar). This is never dealt with directly in the narrative, except that everyone calls her “simple.” When we see her interacting with other people, she is very awkward. One example is the scene when she’s at a Japanese restaurant with Gabrielle (the curator) and we see her trying to figure out how to sit down on the floor. And when Gabrielle orders sake, Polly orders milk, which is a very weird choice to make at a Japanese restaurant. But even though she’s portrayed as someone plain, in her daydreams she’s doing impossible things and she’s in impossible worlds – until something from the real world pulls her back to reality.

“Exploring women’s desires”

According to Fabe, one of the things that makes Mermaids an example of counter-cinema is “the depth with which it explores the dynamics of female psychology, specifically the inner worlds of women … a theme rarely treated in mainstream cinema.” In the film, we see Polly exploring her feelings for Gabrielle. She states that she’s had relationships with men before, but we don’t know if these were sexual or not. Many times, she describes how she’s romantically involved with Gabrielle, but there is an absence of sexuality. In a way, she seems asexual, but I don’t want to label her. The better term for Polly would be bisexual. She’s stated that she’s in love with Gabrielle, but she doesn’t want to have sex with her. And that relationship is never kindled.

Although it was filmed decades years earlier, Where Are My Children? also explores aspects of women’s desires, especially concerning whether they want to have children or not. The topic of contraception was culturally relevant at the time, but it was unusual for this to be the theme of a mainstream film produced in Hollywood. The film’s narrative about birth control - and how abortion is used as a method of birth control by the protagonist, Edith – was very controversial at the time. After the National Board of Review rejected the film, the director went through many edits before the final version was released. And although the film explored Edith’s desires about motherhood and her independent choices, the ending seems to offer the mainstream message that she was wrong to deny her husband the children that he might have had.

“Departures from mainstream cinema style”

Fabe describes how the cinematic style of Mermaids “undermines the mainstream film convention that aligns the spectator with an all-seeing camera eye (the eye of God) with access to an unmediated reality unfolding on the screen before us.” In Mermaids, this style is unusual because it is a person talking directly to the camera. This is similar to the style of some current TV shows such as “Parks and Recreation,” “30 Rock,” and “The Office.” These are all comedies and it’s very apparent that these are fictional but certain parts are played as if these were documentaries. In this way, fictional people are documenting fictional life. In Mermaids, Polly’s recordings operate in the same way. It’s evident what she’s doing and easy to follow along in the narrative. There’s a clear distinction between the actual movie and Polly’s discussions with the audience. At the same time, the style is very different from mainstream films.

A similar cinematic style is used in The Watermelon Woman but with less success, in my opinion. In this film, the style is a lot more confusing and hard to follow. For instance, there are cinematic angles where people are filmed in environments where they don’t see the camera. The style comes across as jumpy as if the story is going in way too many directions. It’s hard to make sense of it and sometimes it feels like a reality TV show to me. It was difficult for me to tell if the film was fictional or not; a lot of times it seemed like both. Many parts of the film made it seem like a documentary, which just added to the confusion. It’s further complicated because the director, Cheryl, stars as herself; so, the fictional version of Cheryl is making a documentary, too. Also, there are many other people in the film who are playing themselves, which blurs the line between fiction and documentary.

“Rethinking cinematic voyeurism”

Mulvey and Fabe argue that counter cinema “subverts most male-centered conventions of female representation by refusing the voyeuristic pleasure of objectifying or fetishizing women and it also interferes with the male-active, female-passive, dynamics of most mainstream films.” The male gaze is often the one that is pushed upon the viewer, as opposed to the female gaze. The intention is that the viewer is supposed to see females as objects, to objectify women. The more mainstream, traditional, approach to voyeurism is evident in the first film we viewed, Rear Window. In Rear Window, we only see everything from Jeffrey’s apartment because he is confined to a wheelchair. So, we can only see the other characters and events from his window and his point of view. Therefore, there are many instances in the film of how his male gaze objectifies women. One example is the ballet dancer who is only known as “Miss Torso” because that is what Jeff calls her. He doesn’t call her “Miss Ballet” or “Miss Dancer.” Instead, he objectifies her by naming her for her body part. And then there’s “Miss Lonely Hearts,” as Jeff calls her. He names her that because he thinks she’s lonely because she doesn’t have a man in her life. So, again, his nickname is more about objectifying her in relation to men.

Fabe discusses the cinematic gaze and how Mermaids takes a different approach to voyeurism. In the film, Polly exhibits a lot of voyeuristic tendencies in her hobby as a photographer. She is always looking for things to photograph. For instance, in the park, she follows the couple into the woods where they are making out. She likes the idea of seeing something new and different and she uses her camera to gather as much information about it as possible. She doesn’t just photograph people, either. For example, she will capture buildings and other touristy sites. We get an idea of all the types of things she photographs when the story shows her in her apartment developing photos in the darkroom. When she does take a picture of people, she wants it to be candid and not posed. An example is when she asks if she can take a picture of the woman with her toddler. In Polly’s photo, the woman is not smiling for the camera. Instead, she is smiling at her kid. So, they are not interacting with Polly’s camera. She wants to just capture a moment. It’s interesting because for Polly it’s like a window into other people’s lives.

Conclusion

Based on what we’ve learned from the films and readings, I do think an argument can be made for a female gaze but not a female aesthetic. However, I think I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing is successful in presenting a uniquely feminist vision on film as counter-cinema. This is accomplished through: the choice of a female protagonist, who is quirky and different; the plot which explores the thoughts and romantic desires of the female protagonist; the cinematic style which falls in the gray area between fiction and documentary; and the way the protagonist’s passion for photography is used in the narrative to redefine voyeurism.

0 notes