#it was lunisolar calendars

Text

tfw you look up a random piece of information and end up finding something to incorporate into your worldbuilding

#it was lunisolar calendars#almyra has one now#it lines up perfectly with my current worldbuilding#and adds in the bonus confusion#of a very concussed claude being asked the date#and giving it based on the almyran calendar#so the year is totally wrong because it has a different starting date#cue everyone either panicking or having the math lady expression#until claude realizes 'wait shit wrong calendar'#and corrects himself#...mostly#(he's still off by a year because fodlan cycles in the twelfth month)#(and he's primed to the equinox as the new year)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resources for Those Wanting to Learn about Pre-Christian Time Reckoning in Northern Europe and its Application in Modern Heathen Traditions

Throughout the history of the modern Neo-Pagan movement, the calendar that has been used by most practitioners has been either the Wiccan Wheel of the Year or another calendar heavily influenced by it. The Wheel of the Year draws largely upon a mixture of Celtic (Gaelic) and Anglo-Saxon traditions, splitting the years into quarters with quarterly and cross-quarterly celebrations and beginning the year at the end of October with the originally Gaelic festival of Samhain.

The calendars that have come to be popular for the majority of the modern Heathenry movement have undoubtedly been based in this calendar, with the major changes being to the names of certain celebrations. On the calendar created by Stephen McNallen for the AFA, Lammas became Freyfaxi, Mabon became Winter Finding, Samhain became Winter Nights, etc. Other organizations such as Forn Sidr of America, The Ásatrú Community, etc. have created their own versions of the calendar as well, but at their roots they all exist essentially as a modification of the Wheel of the Year concept.

More (relatively) recent research and scholarship has brought a greater awareness of older time reckoning systems within Heathen circles as well as amongst history enthusiasts. Some of this has focused on the Old Icelandic calendar as well as the primstav tradition, and while both of these have validity to them the Old Icelandic calendar already had some changes to how it worked from the older system and the primstav used a standardized dating system based in the Julian calendar. Still, these are both useful tools in attempting to reconstruct the pre-Christian (or at least pre-Julian) calendar systems of the Germanic, and particularly Scandinavian, peoples of Northern Europe.

Why is this at all important in an age with the Gregorian calendar used most everywhere and especially for those outside of Scandinavia? Because for those trying the build an understanding of or relationship with these cultures, or even just more connected to the earth in general, the way they reckoned time helps to understand their relationship and connection to their environment, the flow of seasons, how they viewed the different parts of the year and adjusted their activities accordingly, etc. It helps to understand the "why" behind the ritual cycle, even in the names of the months themselves.

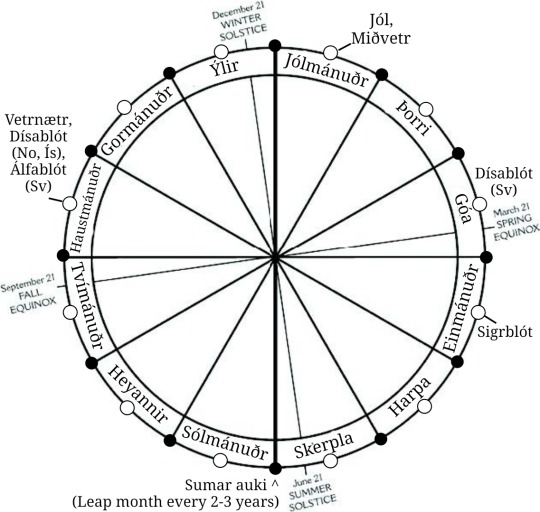

Below are a few of the primary resources that I have found helpful in learning about these topics, as well as a graphic representation that I have made based on my research so far to represent the reconstructed Old Norse lunisolar calendar. Note that I don't claim to be an expert on this topic, so I could certainly be wrong in some of the details, and some of the months also have multiple names from which I chose one to use. Also, there were multiple time reckoning systems in use during the period, including a week-counting system, so there can also be conflicting information depending on which is being considered.

Sources:

"Jul, disting och förkyrklig tidräkning: Kalendrar och kalendriska riter i det förkristna Norden" by Andreas Nordberg

- Available as a free PDF, the majority of this is written in Swedish, but it contains a fairly concise English summary at the end. It focuses primarily on Old Norse Jól (Yule) as well as the Dísaþing/Disting and Dísablót in Sweden, but it touches on other celebrations and uses these to establish the overall scheme of the lunisolar calendar system.

"The Festival Year: A Survey of the Annual Festival Cycle and Its Relation to the Heathen Lunisolar Calendar" by Josh Rood

-Also available as a free PDF, this paper expands upon Norberg's work as well as others' and goes through the overall festival year of the pre-Christian Scandinavians.

"The Lunisolar Calendar of the Germanic Peoples: Reconstruction of a bound moon calendar from ancient, medieval and early modern sources" by Andreas Zautner

-This book is sort of a dive into a number of different ancient to early modern calendar systems, but it uses all of these to reconstruct lunisolar time reckoning systems not only for Scandinavians, but for other Germanic peoples as well. It's a great read for those interested in pre-Julian time reckoning in Northern Europe as well as Medieval calendar systems in general.

"The Nordic Animist Year" by Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen

-Similarly to Zautner's book, Rasmussen draws upon a variety of Medieval calendar systems in his work, but his goal, rather than reconstructing an Old Norse calendar is to create a modern calendar based in animist traditions of Northern Europe. It undoubtedly uses the lunisolar system as a base and takes a lot from Old Norse sources, but it also incorporates later traditions which are based in animist knowledge and have value in establishing a system of seasonal animism.

And lastly, my Old Norse lunisolar calendar representation. Each month starts on a new moon, represented by a black dot, and the festivals are shown at the full moons, being white dots. You may notice the lack of Þorrablót and Miðsumar (Midsommar) on here. Regarding Þorrablót, I'm not as well researched on the origins of it and how widespread it may have been. For Miðsumar I have long refrained from including it due to the absolute lack of mentions in literary material from during or shortly after the period, but I have been pointed to some instances of it marked on primstavs as July 14th (Julian calendar), suggesting a possible lunisolar observance of it earlier similar to Jól's relationship to the winter solstice.

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edo period egoyomi (picture calendar) for Keio 4 (1868), showing the sho-no-tsuki (small or short months) as women and the dai-no-tsuki (large or long months) as men.

Edo Period Calendars

Disclaimer: The following information is from the National Diet Library, I didn't write this. I am sharing it for reference, both for myself and those of you who might be interested. Some slight editing for paragraphs.

...

Background / History

Japan's first calendar came from China via Korea. In the middle of the 6th century, the Yamato Imperial Court, which ruled Japan at the time, invited a priest from a country called Paekche (Kudara in Japanese), in what is now Korea, to learn from him how to draw up a calendar, as well as astronomy and geography.

Reportedly, Japan organized its first calendar in the 12th year of Suiko (604).

Back then, all matters relating to the calendar were determined by the Imperial Court. Under the Ritsuryosei system of centralized administration under the Ritsuryo legal code of the Taika Reformation, the Onmyoryo of Nakatsukasasho was in charge of the task.

An Onmyoryo was a government office that had jurisdiction over calendar preparation, astronomy, divination, etc. It was a time when calendars and divination were inseparable.

From the end of 10th century, the task of preparing the calendar was handed down in the Kamo family, while astronomy passed through generations of the Abe family, its patriarch being Abe Seimei (921-1005), noted as an Onmyo-shi, or specialist in the realm of calendars and divination.

The calendar used then was called "Tai-in-taiyo-reki," a lunisolar calendar, or "Onmyo-reki."

Each month was adjusted to the cycle of moon's waxing and waning. Since the moon orbits the earth in about 29.5 days, adjustment was required and this was done by making months with either 30 days or 29 days, the former, "dai-no-tsuki (long month)," the latter, "sho-no-tsuki (short month)."

Aside from the moon's orbit round the earth, the earth orbits the sun in 365.25 days, which, as we all know, causes the seasonal changes. Thus, merely repeating long and short months gradually produced a discrepancy between the actual season and the calendar. To compensate for this, a month called "uru-zuki," or intercalary month, was inserted every few years to produce a year with 13 months, with the order of longer and shorter months changing year by year.

Unlike our contemporary calendar in which there is no change in the order of months, back then the fixing of a calendar was deemed so important that it was placed under the control of the imperial court and, in the later Edo period, under the superimposed military shogunate.

The calendar established by Onmyo-ryo was called "Guchu-reki," one in which various words indicating seasons, annual events and daily good omens were written in Chinese characters and called "reki-chu (calendar notes)." The Guchu-reki derives its name from the fact that the notes were written in detail.

This Guchu-reki, which was in service until the Edo period, was used particularly by noblemen in ancient and medieval times, individuals based their everyday activities on the calendar. They often wrote a personal diary in the blank spaces or on the back of their personal calendar. These entries remain left valuable historical records of the era.

With the spread of kana, Japan's phonetic alphabet, "Kana-goyomi," a simplified edition of Guchu-reki written in kana, appeared. In the middle of the 14th century calendars started to be printed and soon reached a broader range of users.

As the Edo period wore on and knowledge of astronomy grew more sophisticated, the discrepancy between the calendar and actual astronomical events, such as eclipses of the sun and moon, became an issue, there arose a movement within the shogunate to amend the calendar.

Prior to then, the calendar was made each year based on the Senmyo-reki brought from China in the 4th year of Jogan (862), but as the same method had been used for more than eight centuries, it was deemed consistent with the situation prevailing at the time.

In the 2nd year of Jokyo (1685), a method of making the calendar was devised by Shibukawa Harumi, marking the first attempt by a Japanese, with the amended version known as the Jokyo calendar.

Later in the Edo period, the calendar was revised several times, the results respectively called the Horeki (1755), Kansei (1798) and Tenpo (1844) calendars.

Through these amendments, a more accurate lunisolar calendar was devised incorporating Occidental astronomy. Calendar calculation was made by the "Tenmongata" (officer in charge of astronomy) in the Edo shogunate, with notes added by the Kotokui family, descendants of the Kamo family, after which calendars were issued by publishers in various regions.

Calendars at first were exclusively for the use of the imperial court and noblemen, but after the dawn of printed calendars, more and more people came to use them.

Farmers and merchants found them essential to know the seasons and events. In particular, when using lunisolar calendars in which the order of long and short months changed year after year, learning them proved indispensable for merchants who made collections or payments at the end of each month.

Because of this, various types of calendars were devised and used.

Edo period egoyomi (picture calendar) for Tenmei 7 (1787), showing the sho-no-tsuki (small or short months) as women's parts and the dai-no-tsuki (large or long months) as men's parts in kabuki, beginning with the first month at top right.

According to the lunisolar calendar, there were long months with 30 days and short ones with 29 and their arrangement changed year by year. So knowing the arrangement of long and short months, with the inclusion of an intercalary month from time to time, was very important for the people who lived in those times.

Merchants, who made it a rule to effect payments or collections at the end of each month, would make signs to show a long or short month and erect them up in their shops according to the month in order to avoid mistakes.

While the calendar spread, the Daisho-reki calendar, which showed only the order of the long and short months, appeared during the Edo period (1603-1867). In those days it was called simply "Daisho". But instead of merely showing the length of month, it incorporated such devices as indicating long and short months with the use of pictures and sentences.

Various kinds of Daisho, including those using auspicious illustrations like the animal of the year and scenes from popular Kabuki plays, were produced and many were traded at "Daisho" New Year gatherings, while others were used for gifts. This custom began at the end of 17th century and was most popular in the latter half of the 18th century, in the Edo period.

Many noted artists produced Daisho illustrations. Later, in the Meiji era, when the solar calendar was officially adopted, Daisho calendars fell into disuse and were no longer produced.

#history notes#historical notes#history reference#historical reference#history research#historical research#calendars#calendar#japanese calendar#japanese history#edo period#lunisolar calendar

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Year of the Rabbit

The past few Lunar New Years we have featured paper-cut designs from our copy of Paper-Cuts in China. This year is the Year of the Rabbit in the Chinese zodiac calendar, so we present this bright-eyed paper-cut bunny from Paper-Cuts in China, which features paper cuts of the 12 signs of the Chinese zodiac as well as birds and plants. Lunar New Year falls on the new moon in late January or early February and is based on the Chinese lunisolar calendar.

This book, for which we have not identified the year or publisher, has text in both Chinese and English. It notes that in 2002, “China’s paper-cut was listed as a ‘world cultural heritage’ by UNESCO.” The commentary to the paper-cut rabbit says:

The persons born in the year of the rabbit . . . are careful and tender, and are good at expressing sympathy for others. Having gift in languages and being sharp in eloquence, so they are popular with others. . . . They are sociable, polite, friendly, having plentiful topics, and presenting a good appearance, but dislike arguing with others. They possess a mild temperament which can convert enemies into friends . . . It is easy to produce small misunderstandings, for they are fragile in affection.

View other paper cuts from this collection.

View posts from Lunar New Years past.

#Lunar New Year#Chinese New Year#Year of the Rabbitt#rabbitts#Paper-Cuts in China#Paper Cuts in China#chinese zodiac#Chinese lunisolar calendar#UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage#world cultural heritage

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lunar New Year marks the first new moon of the lunisolar calendar. The holiday is known by different names in different countries. For example, in China it is called Chūn Jié, in Vietnam it is Tết, in Korea it is Seollal and in Tibet it is Losar, just to list some of them. Feel free to mention others in the comments.

To call to it Lunar New Year means it’s inclusive to all who celebrate, as opposed to using the blanket term Chinese New Year. To use the latter implies that the holiday is exclusive to China and the Chinese people.

By casually calling this day “Chinese New Year,” we are forgetting the many other East and Southeast Asian cultures that celebrate the beginning of the lunar calendar. The erasure of those other Asian cultures who celebrate this holiday is important to consider.

It’s indicative of the much repeated pattern of a diverse and multicultural society trying to group seemingly similar cultures together. This speaks to the ways in which Asian people and our culture are often treated as a monolith and experience many generalisations and ste reotypes. I think it’s important for us to be recognised for our differences rather than being endlessly grouped together under the umbrella of “Asians” or “Chinese.”

To this end, I personally feel Lunar New Year is the most inclusive phrase to use (unless you’re certain of one’s cultural background and may therefore decide to be more specific). I still have my moments where I have to correct myself and refer to it as Lunar New Year. Language is important. Making this small change and correcting ourselves is a small step in helping to make people feel included, seen and respected.

Source

Alyssa Ho Writings linktree

#Alyssa ho#lunar new year#chinese new year#Asian cultures#diversity#multiculturalism#whitewashing#language is important#Instagram#long post#Alyssa Ho writings#china#asia#lunisolar calendar#Asian holidays

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

The amount of absolutely batshit comments i have seen on Lunar New Year posts claiming it is a Chinese Invention and therefore must be called Chinese New Year is absolutely fucking bonkers. Anyway, happy year of the cat!

#like seriously someone said the lunisolar calendar was invented in the 70s and that the lunar calendar’s new year is in july#like what the absolute fuck are you fuckers on about???#viet people have been celebrating tet for literal centuries#we have a leap year system to reset the calendar ever so often so the new year continues to fall in the beginning of the solar year#it’s old as balls!! our lunar calendar follows a 60 year cycle!! it is literally impossible for it to have been invented in the 70s

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm so thrown by the dates of easter and pesach this year. i keep seeing easter coming up on the calendar (march 31st) and being like ahhh but i haven't sent pesach cards yet!!! and then i look at my calendar of jewish holidays which keeps telling me it's not until april 22nd. so i just looked up what the deal is and it's because of the leap month!!! i forgot about that guy. but now that you say it, duh. yay leap month 🥰

#the name of this month is awesome it's just adar...2!!!#(the preceding month being adar 1 obviously)#2 SPRING 2 SPURIOUS#actually technically i think adar 1 might be the leap month but now i'm confusing myself#like regular adar gets renamed adar 2 in years with a leap month?#oh according to wikipedia apparently 'sources disagree' about which adar is the REAL adar lol#i would expect nothing less!!#systems of measurement#time#judaism#holidays#we get so excited about leap day but the hebrew calendar has an entire leap month...hello...#it's cuz it's lunisolar <3 i wonder how other lunisolar calendars do it#they must also have leap months? what does the chinese calendar do for instance#i will look it up later if i remember

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the problem with making commitments at the start of a new year on the western calendar is that its january and the vitamin D deficiency hasnt even begun to start chewing us down yet

#we should really switch back to the seasonal calendar for new years#chinese new year really popped off by choosing the first day of lunisolar spring to usher in the year#makes the idea of winter being a time of dormancy and storing up of hopes and dreams for the new year sound a lot more appealing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Thus, the Mesopotamian year was, in effect, a solar year squeezed into a lunar strait-jacket."

—The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East by Cohen page 4

Lunisolar calendars in a nutshell.

#polytheism#paganism#lunisolar#lunisolar calendar#calendar#calendar work#sorta#quote pile#michibooks#am i actually reading a book right now? wtf

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

back on my bullshit

(drinking green tea by the liter)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#On the fourth day of passover the pesach kitty brings a roasted egg to all the good children#and shares a carrot with the easter bunny#happy holidays to all who celebrate national buggle day#surprisingly it's tracked on the lunisolar calendar

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy winter solstice!

In modern times, many people who celebrate Yule begin doing so today, and though it appears that this was not the case during the Early Medieval period it still served an important function and may well have had some lesser celebrations and observances around it.

The Old Norse calendar system was lunisolar, meaning that it reckoned time using both lunar and solar cycles. While the months went from new moon to new moon, and later full moon to full moon on the Old Icelandic calendar, the solstices were used to keep everything in check. Since there are not quite 365 days in the 12 lunar month period that was used, it creates a cycle where the months could continuously move backwards relative to the seasons. The Islamic calendar, for instance, does this, which is why Ramadan can occur in the summer as well as the winter.

With the Old Norse calendar there was an incentive to keep the seasons and months more tightly bound, largely due to the single and in many places short harvest period. In this case, how close the new moon which began Jólmánuðr (Yule Month) was to the winter solstice would determine if an extra month would be added during the following summer. If this new moon occurred within 11 days of the solstice, the extra month would be added after the summer solstice. In this way, the winter solstice was the anchor of the entire year.

This year, Jólmánuðr begins a mere two days after the winter solstice, and as a result this coming summer will see an extra month added by the lunisolar reckoning!

For more information on this, check out Andreas Nordberg's "Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning" and Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen's "The Nordic Animist Year".

#yule#jól#heathenry#asatru#pagan#jul#jólatíð#yuletide#winter solstice#heathen#norse#oldnorse#lunisolar calendar

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy QiXi/Chilseok everyone!!

#also Tanabata if you follow the lunisolar calendar! i know some places in japan celebrate it on different days#rose speaks

1 note

·

View note

Text

I got a plot bunny last night and I’m really excited about it but I can’t stop thinking about the calendar

#my writing!#i know I say my one true love is time travel#but it’s spreadsheets#and building a lunisolar calendar is a GREAT way to spend hours in excel

0 notes

Text

#Nepal Sambat is the lunisolar calendar used by the Newari people of Nepal. The Calendar era began on 20 October 879 AD#with 1143 in Nepal Sambat corresponding to the year 2022–2023 AD. Nepal Sambat appeared on coins#stone and copper plate inscriptions#royal decrees#chronicles#Hindu and Buddhist manuscripts#legal documents and correspondence. Nepal Sambat is declared a national calendar in Nepal#is used mostly by the Newar community.#नेपाल सम्बत ११४३ या लसताय् सकल नेपामी पिन्त यक्वो यक्वो भिंतुना देछाना।#नया वर्ष ने. स. ११४३ को उपलक्ष्यमा सम्पूर्ण नेपालीहरुको उत्तरोत्तर प्रगतिको कामना गर्दछाैं।#HAPPY NEW YEAR 1143!#gemsartsjewellery#HNY#hny1143#HappyNewYear#festival#nepalsambat#Nepal#kathmandu#kathmanduvalley#kathmandunepal#mhapuja#swonti#tihar#festivaloflight#diamond#diamonds#gold#silver#gems

1 note

·

View note

Text

Happy new year!... Again

Bonus Akechi because I forgot the baby I'm sorry

Akechi's yapping under the cut.

The New Year is the time or day at which a new calendar year begins and the calendar's year count increments by one. Many cultures celebrate the event in some manner.In the Gregorian calendar, the most widely used calendar system today, New Year occurs on January 1 (New Year's Day, preceded by New Year's Eve). This was also the first day of the year in the original Julian calendar and the Roman calendar (after 153 BC). Other cultures observe their traditional or religious New Year's Day according to their own customs, typically (though not invariably) because they use a lunar calendar or a lunisolar calendar. Chinese New Year, the Islamic New Year, Tamil New Year (Puthandu), and the Jewish New Year are among well-known examples. India, Nepal, and other countries also celebrate New Year on dates according to their own calendars that are movable in the Gregorian calendar.

An example of another new year is Chunyipai Losar, the traditional day of offering ( Dzongkha: buelwa phuewi nyim) in Bhutan. It is observed on the 1st day of the last month of the Butanese lunar calendar. This means it usually takes place in January or February in the western calendar.And this year falls on 12th of January. Some people claim that residents of Bhutan made their annual offering of grains to Zhapdrung Ngakwang Namgyel in Punakha on this day. The Trongsa Penlop is said to have led the representatives of eight eastern regions in their offerings, as the Paro Penlop coordinated the people of western Bhutan and the Darkar Ponlop oversaw the people of the south. In this regard, some people place a great significance on this New Year as a marker of Bhutan’s sovereignty and solidarity. However, some scholars contest that no clear evidence of such practice exists. In any case, many feel that before Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal’s unified Bhutan as a state, the local population in some of Bhutan’s valleys celebrated this day as a New Year. As a result, even the government instituted by Zhabdrung in the 17th century, then largely a monastic court, saw this time as an important part of the year. The retirement and appointment of high officials in the government and the monastic body took place mainly during this New Year celebration.This New Year is primarily observed in eastern Bhutan, where it also referred to as Sharchokpé Losar, or New Year of the eastern Bhutanese. However, the observance of this New Year is not limited to eastern Bhutan and today with easy communication facilities, migration of people and intermarriages between various regions of Bhutan, people all over Bhutan observe this New Year. Like other Bhutanese seasonal festivals marking a new season, the Chunyipai Losar falls around the Winter Solstice. It also falls after the agricultural work for one season is completed and before the new harvest cycle begins. Thus, it is a seasonal celebration which is aligned well with the agrarian populace.

At the end of the day this is all inane information that the artist is using to justify the fact that they are posting this drawing 12 days late and as a means to share their culture despite the fact that the artist themselves are very out of touch with thier culture and in fact forgot that it was chunyipi losar until they were reminded by thier family and did little to observe or celebrate the day outside of baking a cake with a concerningly large amount of butter.

#i love you touma#never shut up#the disaster of psi kusuo saiki#the disastrous life of saiki k.#saiki no psi nan#saiki k#saiki kusou no psi nan#kusuo saiki#saiki fanart#toritsuka reita#aiura mikoto#touma akechi#pk psychickers#I love you touma i love you#sorry hes my precious little silly guy#i cant believe i forgot him#oh oop made a typo its fixed now

190 notes

·

View notes