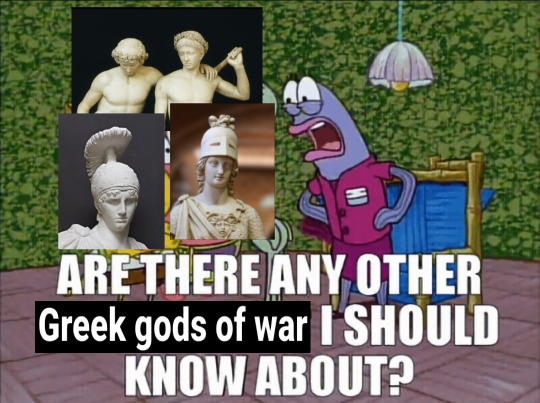

#it took philip of macedon to conquer them for the greeks to unify

Text

#greek mythology#those greeks sure do love warring#mostly with other greeks#it took philip of macedon to conquer them for the greeks to unify

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Dr. Reames!! Oftentimes I see it mentioned that Alexander’s Persian campaign was framed at the time as a revenge against Persia for previous wars against Greece. And so, for example, the burning of Persepolis could be interpreted as payback for the burning of Athens.

But how accurate is that actually? I can only suppose that the top echelons of the Macedonian military establishment didn’t really feel that strongly about Greece as a whole (as Greece wasn’t a unified country like today), but had to frame it as such to disguise what could be seen as a shameless offensive land grab.

Even so, Alexander knew his propaganda. Was there a general feeling among the people of Greece and the rank and file troops that this campaign was a revenge for the previous wars Persia waged against Greece? Some sort of unifying spirit, ideal? And Alexander exploited this for his benefit? Or is this idea of a Greece vs Persia conflict a complete fabrication of misinterpretation?

The idea of a “Revenge against Persia” campaign was part of 4th century political discourse before Alexander, or even Philip. The question was who would lead such a campaign? Naturally, Athens thought they should, but after their defeat in the Peloponnesian War, didn’t have the military mojo. And even if Sparta had opposed the Persian invasion (alongside Athens), she owed her success in the Pel War to Persian assistance, so that was a problem. Thebes as a potential leader was even worse, as she’d Medized (went over to the Persians), so hell-to-the-no would she be appropriate.

Isokrates was probably the first to suggest it be Philip, as his star was rising. Yes, Macedon had also Medized, but Alexander I had been a clever man who played both sides against the middle and was able to burnish his rep after the war as “having no choice, and see? I helped Athens by providing her with timber for the Greek fleet”…if at, we’re sure, a substantial sum that benefited Maceon. But Macedon resented Persia too and had been a victim! It provided the plausible deniability needed to elevate Philip as leader of the Go-and-get-Persia campaign.

Of course Athens was not keen on this. She still thought SHE should be leading the vengeance war, as she won the two most significant battles of the Greco-Persian Wars (Marathon in #1 and Salamis in #2). That Philip was out-maneuvering her at every turn for the hegemony of greater Greece was additionally galling.

When Philip decided to invade Persia is a point of great contention, but I think he had it in mind by the time of his extensive Balkan campaign (c. 341/40/39. when Alexander was left in Pella as regent). Much of that was to secure the Black Sea coast and conquer Perinthos and Byzantion (Athenian allies) in order to secure a bridgehead to Asia. He may have believed that the Athenian Isokrates’s oration letter to him was indicative that Athens could be won over as an ally, in order to provide the ships he needed but didn’t have. He knew Demosthenes a problem, but may not have believed fear of/resentment against Philip himself would unite Thebes and Athens (inveterate enemies) to oppose him at Chaironeia.

But that’s how it went. Philip won anyway and created the Corinthian League, whose purpose was the invasion of Persia and vengeance for the earlier Persian invasion of Greece. Was that Philip’s primary motivation? Oh, hell no. He wanted the MONEY/loot (and glory). But a campaign of retribution put a better face on it, and justified his usurpation of the Athenian navy, which he absolutely had to have to be successful.

When Philip was assassinated, Alexander simply took up where his father left off. He literally told the Corinthian League (when he reconvened them not long after Philip’s death), “Only the name of the king has changed….”

So yes, the propaganda wasn’t invented by Alexander, or even by Philip, but they used it to very good effect, as it allowed them to demand allies (and BOATS). Alexander didn’t dissolve the alliance and release those troops until after Darius’s death. And even then, he offered good pay to stay on with the rest of his conquests (which many did).

#asks#philip ii of macedon#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#Greco-Persian Wars#Alexander's campaigns#Isokrates#Isocrates#ancient Athens#Greek revenge campaign against Persia#Classics

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay thanks to movies and series many foreigners are aware of the Trojan and the Thermopylae war (with the 300 Spartnas). But i believe not many know other important battles that happened during ancient Greece.

Which ones do you think are also worth mentioning?

Just some clarifications for interested people who might not know:

While the Trojan War (sometime in c. 1299 BCE - c. 1100) did happen, we have no idea how accurate any realistic event in the Iliad is. The only thing we know is that the consequences of the war were terrible for both sides. The aftermath is believed to have led to a period of deep regression even in victorious Greece, which is known as the Dark Ages.

The Battle of Thermopylae (not war) (480 BC) is a very real battle, part of the ongoing Persian Wars, meaning the attempts of the Persian Empire to conquer the Greek city-states. While the battle was a defeat stained by treason, the conscious sacrifice of the tiny Greek army caused an uprise of pride and resistance from the Greek people, who up to that point were torn as to whether they should fight or not risk opposing to the massive empire. This is why this battle is considered so important.

So some other turning points in Ancient Greek war history were:

The Battle of Marathon (490 BC). First victory of the Greeks against the Persian King Darius I, despite his much larger forces. The Athenian general was Miltiades. Darius wouldn't return but his son Xerxes attempted to materialize his father's dream 10 years later. Western scholars deem this one of the most significant battles in world history.

Naval battle of Salamís (480 BC), Battle of Mycale (479 BC) and the Battle of Plataea (479 BC). Greek victories. In the Battle of Plataea, the Greeks finally manage to create a big army (for Greek standards). This was the final battle that ended the Persian ambitions over Greek territory once and for all.

Many important battles took place during the Peloponnesian War (431 - 404 BCE) but since this was just something that we nowadays would call a hell of a civil war, I don't think it matters a lot to analyze it here. Just imagine literally everyone fighting literally everyone.

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC). While this is a battle belonging to the great sphere of the violent infighting started and perpetuated after the Peloponnesian War, I'm gonna mention this one because it did change history forever. King Philip II of Macedon alongside the Epirotes, Thessalians, Aetolians, Phoceans and Locrians defeat the usual elites of the Athenians, Thebans, Corinthians, Achaeans, the Chalcidians of Euboea and the Epidaurians. This begins the Macedonian hegemony over Greece, that will lead towards the dissolution of the Greek city-states, the disempowerment of mighty Athens and Sparta, but also the rise of the Macedonian Empire and a more unified sense of Greek identity, in the grand scheme of things.

We talking great battles, right? Not just “side of the angels”... Greeks have given historically significant battles where they were on the offensive, too.

Battle of Issus (333 BC). The Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great defeats the Persian Empire and acquires Asia Minor.

Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC). Under Alexander, Greeks take full control of the Persian Empire.

Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC). Alexander marches against what is modern-day Pakistan and reaches the outskirts of India.

And we should mention the history-changing defeats:

Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC). The Greek King Pyrrhus of Epirus was asked by the Greeks of South Italy to help them against the rising and expanding Roman Republic. Pyrrhus indeed gave great and demanding fights on their behalf, nearly all of them victories, however these victories were so costly that in the end they turned against the exhausted Greek populations. His victories were soon overturned by the Romans, making famous the phrase “Pyrric victory”, which roughly means “winning the battle and losing the war”.

Battle of Pydna (168 BC). After an initial Greek advantage, Romans eventually defeat the Macedonians and take control of the northern Greek lands.

Battle of Corinth (146 BC). Romans utterly destroy the city of Corinth in the Greek South and assume power over the entirety of Greece, which becomes part of the Roman Empire.

War of Actium (32-30 BC). Long story short, the Romans acquire more and more of the lands once taken by the Greeks. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt has been going through civil wars, harbored by the Romans. In the War of Actium taking place in Greece and Egypt, Cleopatra and her Roman ally Mark Anthony are defeated by the Roman Emperor Octavian. This is a defeat of the Egyptian people but also the last nail in the coffin of Greek hegemony in the ancient world.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander III “The Great”, King of Macedon (356-323BC) Part 1: The lay of the land...

His name conjures up all kinds of images and associations and the details of his life which spanned just shy of 33 years are far too expansive to be condensed into one post, so we’ll divide it into a few parts with a summary focus on what brought him to historical attention, his military conquests and some of his lasting impacts on culture and history. First a bit of personal and geopolitical background are necessary.

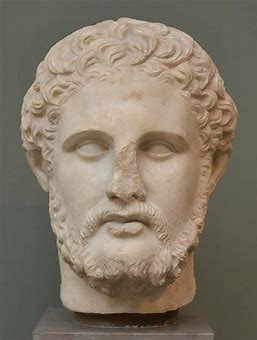

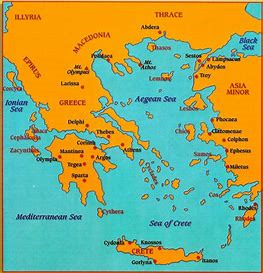

Alexander was born in July of 356 BC in what is the city of Pella in the ancient Kingdom of Macedon in modern northern Greece. His father was the then reigning King of Macedon, Philip II and his mother was one of Philip’s wives Olympias, a princess from another Greek kingdom, Epirus. Ancient Greece was divided into city-states or polis or various small petty kingdoms without a unified rule in the 4th Century BC. In centuries prior, Greece was dominated by two cities with two different systems of government and two different military traditions. One was Athens, a direct democracy with an advanced and powerful navy and the other was the largely land based diarchy (two co-ruling kings) of Sparta, which was famed for its infantry and harsh military indoctrination with a reputation as an almost unbeatable force in the Classical Greek world. Both played an important role in establishing Greek culture, philosophy, art, religion, military and government, all of which would contribute to modern Western Civilization.

Athens and Sparta were at times friendly but often rivals and most especially in the 5th Century BC with the invasion of Greece by the great superpower of the day in Eurasia, the Achaemenid Empire, better known as the Persian Empire from Iran. The Persian Empire spanned from the Indus River valley in modern Pakistan and India across Central and Western Asia, the Middle East, Northern Africa and Southern Europe, it was multiethnic, multilingual, multireligious, cosmopolitan and very influential on governance. It was centered in Iran, by the Persians, an Iranian people of the diverse Indo-Iranian ethnolinguistic group that overtook many others and expanded to become the predominant power of its age, probably in the entire world. The Greek or Hellenic world was on Persia’s western fringe, it was a tributary portion, subject to the Persians but with a modicum of independence. Persia’s provinces were divided into satrapies, ruled by royal governors called satraps. Persia invaded Greece under Xerxes I, its Shah or King of Kings in 480 BC. This united Greece and was famed for the stand of the Greek force, namely the 300 Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae, which though a Persian victory was costly in lives and time, delaying the Persians. Eventually the Persians retreated due to rebellion back east and the force that remained was defeated by the Greeks, giving the Greeks breathing space to maintain their independence. In the wake of this victory though Athens and Sparta and their various other Greek allies turned on each other forming rival camps in the Peloponnesian War which saw Sparta defeat Athens and become the most powerful faction in Greece.

Meanwhile to the north in the highlands, Macedon was remote and rustic for a Greek kingdom, it was viewed as a backwater by its southern neighbors and some did not consider it Greek at all. Though they are believed to have spoke their own dialect of Greek, worshipped in the same polytheistic religion as Greece and shared certain other cultural traits with the southern Greeks. Nevertheless their proximity to the barbarian tribes of the Balkans, the Thracians, Dacians and Illyrians made them some what of a halfway point between “civilized” Greece and outright barbarians. However, the ruling dynasty into which Alexander was born, the Argead claimed descent from the legendary hero Heracles or Hercules and from there Zeus, God of Thunder and supreme on the Greek Pantheon of Olympian Gods. They were famed for their military tradition, including cavalry and their infantry. It was really Alexander’s father Philip who introduced the innovations to Macedon’s military that Alexander would perfect in later battles.

Their reforms were a result of technology, regimented drilling and a doctrine of combined arms, something most Greek military traditions up to that point ignored. Typical emphasis was on one branch of the military, in Athens it was naval warfare, in Sparta, a strong infantry and Thessaly a strong cavalry. Macedon lacked naval power at the time but it sought to emphasize both strong cavalry and infantry tactics in combined usage, one supporting the other throughout the battle. Philip adopted tactics from his enemies, including the light infantry tactics of the Thracians, the light cavalry of the nomadic horse archer Iranian Scythians including their flying wedge tactic. Most famously, Philip helped innovate a new technological and tactical formation, the phalanx.

The phalanx was a formation of regiments of heavy infantry using long spears called the sarissa, typically 18-20 feet long in units numbering 256 men each armed with a speared pike that was light in construction but due its length could keep the enemy at bay. Phalanxes were both defensive and offensive in nature. Its long spears meant it could defend itself at greater range in melee, deflecting cavalry and infantry charges head on and by going on the offensive and marching in formation, the phalanx could deploy to hold or press open the enemy line by fixing it into place in such a way that a gap could open for the Macedonian cavalry to exploit with its flying wedge formation, typifying the use of combined arms.

Macedonian troops were drilled constantly, almost as much as Spartans but in a much looser more flexible and adaptable doctrine, making them more well rounded than their Spartan counterparts. Philip would conquer the famed city of Thebes as well as defeat several barbarian tribes and went onto conquer much of Greece and got Athens to make peace but he never took on Sparta, nor did Alexander. Nevertheless, with Macedon now the dominant power over Greece, Philip was named Hegemon of the Hellenic League, making him in effect the ruler of a mostly unified Greece. His goal was to next invade the Persian Empire which was on the decline but he was assassinated by his own bodyguard.

At age 20, Alexander took the throne of Macedon, becoming the king but his rule was in jeopardy, Alexander, however was a learned young man, thanks to his father hiring the famed Aristotle to be Alexander’s childhood tutor. This well rounded classical education combined history, geography, mathematics, biology, philosophy and literature, all things which Alexander came to appreciate and support, but his military training was all from his father and his father’s trusted generals, many of whom Alexander now inherited himself.

Alexander would have to prove himself and his kingdom worthy of his father’s legacy while at the same time forging his own name. He defeated both Thracian tribes to the north in modern Bulgaria and other Greek states, which like his father named him Hegemon and in 334 BC when he crossed the Hellespont from Greece into Asia Minor (modern Turkey), his forces would embark on a ten year campaign that would change the world and one from which he would never return home...

#Alexander the Great#philip ii of macedon#macedonia#ancient greece#ancient world#military history#persian empire#combined arms#military tactics#phalanx#sarissa#athens#sparta#aristotle#classical greece#4th century bc#5th century bc

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

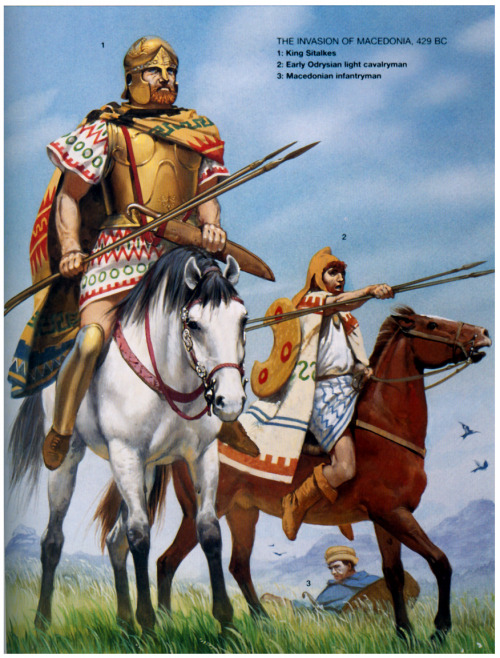

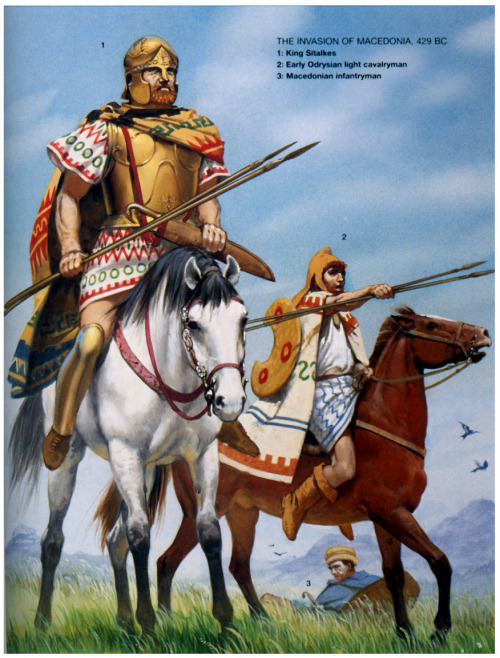

THE THRACIANS AT THE TIME OF KING SITALCES (431–424 BCE)

This is an excerpt from my post, ‘THRACIANS, REAPERS OF THE BALKANS’

Sitalces and the Scythians:

Teres’ son and heir, Sitalces, expanded its borders north to the Danube River, west to the Strymon River (Struma) and southwest to the rich Greek trade port colony of Abdera by the northern Aegean Sea. The Greek colonies within the borders of his kingdom paid the Odrysians tribute as well as the occasional gifts of “gold and silver equal in value to the tribute, besides stuffs embroidered or plain and other articles” (Thucydides, 97.3).

“By these means the kingdom became very powerful, and in revenue and general prosperity exceeded all the nations of Europe which lie between the Ionian Sea and the Euxine; in the size and strength of their army being second only, though far inferior, to the Scythians.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 97.5.

An early threat faced by Sitalces came in the form of a nephew named Octamasades who was of mixed Thracian and Scythian descent. This Octamasades usurped the Scythian throne from Scyles, his half-brother, who was disliked for the fact that he was half Greek, could read and speak Greek, married a Greek woman, built a house in the Greek trade colony of Olbia (north Black Sea coast), as well as publicly practicing the Greek Dionysian sacred rites. Scyles fled into Thrace seeking refuge. Octamasades chased after him but was met at the Danube River by Sitalces of Odrysia who sent Octamasades a message:

“Why should we try each other’s strength? You are my sister’s son, and you have my brother with you; give him back to me, and I will give up your Scyles to you; and let us not endanger our armies.” – The Histories by Herodotus, 4.80.3. Both sides agreed and Octamasades beheaded Scylas.

Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE):

The Athenian-led Delian League succeeded in expelling the Persians from Europe and claimed the coastal regions of the northern Aegean Sea (the Hellespont, Thrace, Amphipolis and the Chalkidikian Peninsula) where they continued establishing colonies. Colonies were even founded deeper into Thrace, Amphipolis for example. One reason for their interest in Thrace was its rich and abundant gold and silver mines. With the Greek triumph over Persia, the Athenians and their allies effectively held dominion over the majority of the Aegean Sea, its coastlines and its islands. We refer to this grand Athenian hegemony as the Athenian Empire.

^ The expanse of the Athenian-led Delian League in 431 BCE, before the Peloponnesian War.

The Athenian empire was now tyrannically imposing their control over allied Greek city states and the rich trade networks of the Aegean Sea but was plagued by rebellions. Sitalces allied himself with the Athenians, promising them aid in Thrace if they helped him conquer the Chalkidikian peninsula (which had recently left the Athenian-led Delian League) which was to the east of Macedon. To this end Sitalces assembled an army of “more than one hundred and twenty thousand infantry and fifty thousand cavalry” (Diodorus, 12.50.3).

“many of the independent Thracian tribes followed him of their own accord in hopes of plunder. The whole number of his forces was estimated at a hundred and fifty thousand, of which about two-thirds were infantry and the rest cavalry.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 98.3.

Macedon under King Perdiccas II, which impelled the Chalkidikians into rebelling against Athens, was at odds with Athens so Sitalces invaded Macedon in 429 BCE. Sitalces was also spurred to invade Macedon with the purpose of placing Amyntas (Perdiccas’ nephew) on the Macedonian throne; Amyntas and his father were previously driven out from Macedon and sought refuge with Sitalces’ court.

“And since he was at the same time on bad terms with Perdiccas, the king of the Macedonians, he decided to bring back Amyntas, the son of Philip, and place him upon the Macedonian throne.” – The Library of History by Diodorus Siculus, 12.50.4.

Sitalces ravaged the lands of both the Chalkidikians and the Macedonians, the latter feared to face this great army so some submitted to the Thracians while others gathered their crops and hid within their strongholds. The momentum waned as Sitalces saw that the Athenians had failed to fulfill their promise to aid the Odrysians with ships and an army, that the harsh winter was wearing down his men and that the Greeks (Thessalians, Achaeans, Magnesians, etc.) were assembling a vast army to repel them. Sitalces and Perdiccas II of Macedon came to terms, the Odrysians retreated and Perdiccas’ gave his sister’s (named Stratonice) hand in marriage to Sitalces’s nephew (Seuthes I). Sitalces, just like his father, died while trying to unify the Thracians (the Triballi killed Seuthes, the Thyni killed his father Teres).

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 360 – The Thracians, 700 BC-AD 46 by Christopher Webber and Angus McBride (Illustrator). Plate A: The Invasion of Macedonia. A1: King Sitalces – “The Thracian king is based on archaeological evidence and wears a bronze bell cuirass, bronze Chalkidian helmet, bronze greaves, and a Thracian cloak. He carries two javelins and a kopis. His breast plate is decorated with dragons’ heads, and his helmet with a griffin and palmettos. The helmet comes from an unknown site in Bulgaria and is dated to the second half of the 5th century. The silver harness ornaments come from Binova tumulus in Bulgaria”. A2: Early Odrysian light cavalryman – “This horseman is based on a painting on a 5th century pelike from Apollonia. He carries two javelins, and a pelta is slung on his back. Greek vase paintings show Thracian light cavalry dressed the same as the peltasts, in patterned tunic, foxskin cap, fawnskin boots and long cloak. Other less sophisticated cavalry dressed very simply in a pointed hat and long flowing tunic, and they are indistinguishable from Skythian cavalry. Some 4th century Thracian metalwork shows the cavalrymen bareheaded and with bare feet, a medium-length flowing cloak and simple tunic.” A3: Macedonian infantryman – “The Stricken Macedonian infantryman comes from the early 3rd century Kazanluk tomb paintings. He is thought to be Macedonian because of his location on the frieze, and his peculiar hat resembling the kausia of the Macedonian warrior nobility; but he may be Thracian, because the Macedonians do not use oval shields, and because of his similarity to the Thracian warriors on the same painting. He wears a blue cloak and carries a kopis and two javelins. His shield is oval with the top and bottom cut square, like the later Celtic thureos. A 5th century Macedonian infantryman would be carrying a circular wicker shield, animal-skin cloak and wearing sandals (or going barefoot) instead of shoes.”

During the Peloponnesian War, thirteen thousand javelin-wielding swordsmen from the Dii tribe (Thracians) were hired by the Athenians to act join in the Sicilian expedition but they arrived too late. The Athenians sent them back to Thrace since they did not wish to be burdened into paying mercenaries they couldn’t make use of. This changed, however, when a series of failures befell them which pressured them into hiring the Thracian mercenaries once again as coastal raiders. When these Dii (Thracian) mercenaries arrived at the Boeotian city of Mycalessus:

“[4] The Thracians, bursting into Mycalessus, sacked the houses and temples and butchered the inhabitants, sparing neither youth nor age, but killing all they fell in with, one after the other, children and women, and even beasts of burden, and whatever other living creatures they saw; the Thracian race, like the bloodiest of the barbarians, being ever most so when it has nothing to fear. [5] Everywhere confusion reigned and death in all its shapes; and in particular they attacked a boys’ school, the largest that there was in the place, into which the children had just gone, and massacred them all. In short, the disaster falling upon the whole town was unsurpassed in magnitude, and unapproached by any in suddenness and in horror.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 7.29.4-5.

Their victory was short-lived however since the Thebans (Boeotians from the city of Thebes) rushed to the aid of the pillaged city and utterly slaughtered the Dii (Thracians) mercenaries. The Thebans took back the looted goods and pursued the fleeing Thracians back to their ships where the “greatest slaughter took place while they (the Thracians) were embarking, as they did not know how to swim” (Thucydides, 7.30.2).

“those in the vessels on seeing what was going on onshore moored them out of bow-shot: in the rest of the retreat the Thracians made a very respectable defence against the Theban horse, by which they were first attacked, dashing out and closing their ranks according to the tactics of their country, and lost only a few men in that part of the affair. A good number who were after plunder were actually caught in the town and put to death.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 7.30.2.

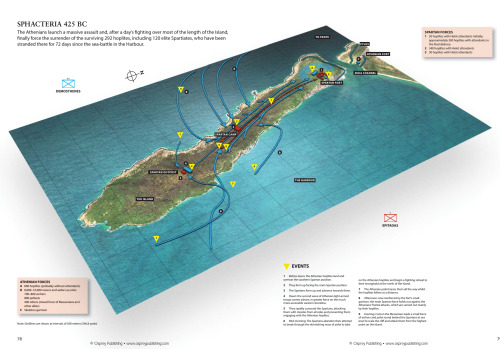

Battle of Sphacteria, 425 BCE:

The famed Athenian politician and general Cleon rallied support from his countrymen by conveying his lack of fear against the Spartans, boasting that he could overcome the Sparta’s within twenty days’ time and declaring that he would achieve this without risking the life of a single Athenian by instead employing foreigners like Thracians peltasts from Aenisas. These Thracians took part in one of the greatest triumphs over the famed Spartans. After the Athenian naval victory over the Spartans (Battle of Pylos, 425 BCE) and its succeeding skirmishes, the remnants of the Spartan forces became stranded on the nearby island of Sphacteria.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 261 – Pylos and Sphacteria 425 BC by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (illustrator). (pg. 78-79).

Here the Spartans were besieged into starvation, dehydration and exhaustion then constantly pursued by Athenian hoplites while being harassed by enemy archers, javelinmen and slingers until they were forced to surrender.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 261 – Pylos and Sphacteria 425 BC by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (illustrator). The Battle on the island: the Spartan last stand (pp. 82–83). “After a fighting retreat over more than half the length of the Island the main Spartan force, depleted by casualties, joined the small garrison in their naturally defended and partly walled stronghold on the highest point at the north end, overlooking the Athenian position across the narrow channel separating Pylos from the Island. For most of the rest of the day they defeated all Athenian attempts to dislodge them. They were much less vulnerable to missile attack and were at last able to do what they did best to beat off efforts to force the position with spear and shield, but they now had little or no water. However, the Athenians could not afford to wait for them to collapse from dehydration because they too had supply problems with their much larger force. Then Comon the Messenian and his mixed, non-hoplite force, managed to work their way round to the rear and scale the cliffs without being seen. They crossed the dead ground in the saddle behind the peak in the centre of the Spartan position and occupied it (1). This is the moment when the small force of about 40 archers, slingers and javelin men attack the defenders from above and behind at a range of 20–30m. ‘The Spartans were now under attack from front and rear and were in the same dire situation, to compare small things with great, as the men at Thermopylae. Just as those men were annihilated when the Persians outflanked them by taking that path, so these Spartans could not hold out any longer now, caught as they were between two fires. They were few fighting many and weakened by lack of food, and they began to fall back with the Athenians controlling every approach to their position’ (IV.37). The Spartans’ weakness would actually have been due to lack of water and probably sheer exhaustion. They may well have had nothing to eat all day but they were not actually starving; Thucydides later mentions that the Athenians discovered a stockpile of food on the Island. In the southern sector the thin Spartan line combining Spartiates (2), perioikoi (3) and Helot attendants (4) is holding firm on the natural and manmade defensive perimeter while the more numerous Athenians hang back as the first missiles find their target. The Harbour with the captured Spartan ships at anchor (5) and the Messenian mainland (6) are in the background to the east.”

At the end of this so-called Battle of Sphacteria, 292 Lacedaemonians (Greeks living under the Spartan state) were taken captive, 120 of which were Elite Spartiates (“Spartans”, full citizens of the Sparta) and the rest being either perioikoi (non-Spartan inhabitants of Lacedaemonia) or Helot attendants (serfs). Athens threatened to kill the captives if the Spartans were to set foot in Attica (region around Athens), holding this over their heads until a series of military setbacks and deaths of high leading commanders on both sides (Sparta’s Brasidas and Athens’ Cleon) opened the path to peace in 421 BCE (Peace of Nicias).

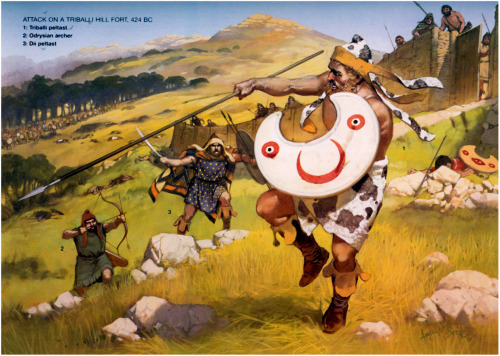

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 360 – The Thracians, 700 BC-AD 46 by Christopher Webber and Angus McBride (Illustrator). Plate C – Attack on the Triballi Hill Fort, 424 BC. CI: Triballi peltast – “In 424 Sitalkes attacked the Triballi, and died fighting them. Thracians retreat to their hill forts when attacked; Tacitus (Annals, XLVII) later described the bolder warriors singing and dancing in from of their ramparts. Here a Triballi peltast armed with a long spear wears an unusual dappled cow-hide outfit that only partially covered his body, this is taken from an example of Greek illustrated pottery.” C2: Odrysian archer – “The costumes on this plate are partially based on a scene on a 6th century Attic amphora showing peltasts, an archer, and a cavalryman in combat. This figure is also based on a 4th century silver belt plaque from north-western Thrace showing an archer with beard, plain conical cap, composite bow, and pattern-edged tunic. He would also have a quiver hanging from the waist belt, and possibly a dagger. The quiver would have held around 100 arrows, and would probably have been made from leather. The decomposed remains of quivers made of some organic material, probably leather, have been found at a tomb near Vratsa.” C3: Dii peltasts – “This warrior is armed with a machaira. Many types of curved swords have been found in Thrace, and this example is based on a weapon now on display in a Bulgarian museum. He also carries a circular pelte – as discussed in the text, not all peltai were crescent shaped.”

Head over to my post, ‘THRACIANS, REAPERS OF THE BALKANS’, to learn about their culture, religion, weaponry, armors, battle tactics, and their influence on the ancient world. Their history as well, from the tales in the Iliad to the era of the Greco-Persian Wars, the rise of Macedon under Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, and the Roman conquests of the Balkans.

199 notes

·

View notes