#indian genealogy

Text

#imeuswe#indian family history#indianfamily#indian genealogy#indian family genealogy#indian family stories#genealogical indian record collections#indian ancestry#familytree

1 note

·

View note

Text

Freedmen Series: Cherokee Freedmen Genealogy Resources

youtube

#Youtube#Dawes#Dawes Act#Dawes Rolls#Cherokee Freedmen#Chickasaw Freedmen#Freedmen#Native American Freedmen#Citizenship#Native Citizenship Genealogy#Black Indians

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day of Commemoration for the Acadian Expulsion

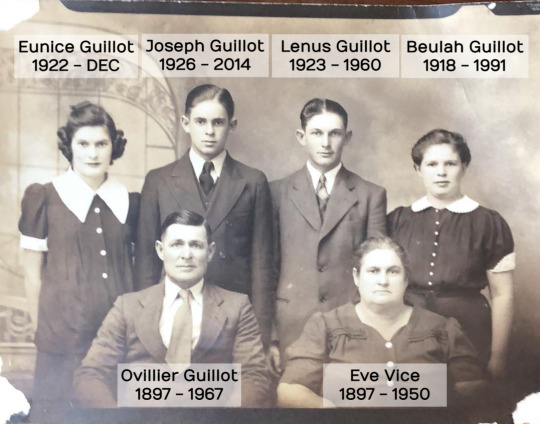

Image Description: A black and white portrait of the Ovillier Guillot and Eve Vice family, circa the early-to-mid 1900s. Top (children), left to right: Eunice Guillot 1922-Dec; Joseph Guillot 1926-2014; Lenus Guillot 1923-1960; Beulah Guillot 1918-1991. Bottom (parents), left to right: Ovillier Guillot 1897-1967; Eve Vice 1897-1950.

The two daughters wear similar dark, button-down dresses with white doll collars. The mother wears a dark, button-down open-collar blouse or dress. The two sons and the father wear white dress shirts covered by fastened suit jackets complete with ties.

Image by [[TBD]].

— — — — — — — — —

Pictured above is my 3rd great-uncle Ovillier Guillot and his family. He is the 4th great-grandson of Jean Baptiste Guillot.

Today is the Day of Commemoration for the Acadian Expulsion.

While I have quite a few direct ancestors who lived in Nova Scotia and ended up in France at the time of the expulsion, there's only one family unit that I have been able to confirm was expelled.

That was the family of my 8th great-grandfather Jean Baptiste Guillot, born in Acadia in 1720 with his body given to the Atlantic Ocean in 1758. His family was expelled from Cobequid, Acadia, Nova Scotia to France during the brutal "Great Expulsion" by the British, who wanted to squelch any potential threats from the Acadians and the Mi'kmaq during the French and Indian War.

His son (my 7th great-grandfather) Charles Olivier Miquel Guillot was only 13 in 1758 when they had to take the long, arduous 75-day journey to France. His father Jean, along with 4 of his brothers, never made it off of the ship.

Charles grew up in France where he married and had 3 children of his own. They left France in 1785 to board one of the seven ships paid for by Spain, Le Saint-Rémi, to take them to Lafourche Parish, Louisiana.

Many members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (I believe predominately it was the Mi'kmaq militia), in addition to other affiliated Indigenous tribes and Acadians, who rallied a resistance were slaughtered or expelled. They refused to swear loyalty to the British crown and surrender to British colonists, refused to convert from Catholicism to Protestantism, and refused to allow themselves to be displaced without a fight. Numerous battles took place to stop the deportation with wins and losses across the board.

While no one has one lineage, I was raised as a proud Cajun despite having often felt ashamed of being Cajun for various reasons (like my accent). I even tried my hardest over twelve years to banish anything that could link me to my roots, not knowing the history behind a part of my ethnicity and culture.

Digging into my ancestry has been a wild ride, and there were many things found within my lineages that were not honorable in any way, but this chunk of my history? This has made me proud to be Cajun again.

I wish I had respected it more when I was still able to be immersed in it. I wish I had asked my pawpaw to tell me more stories. I wish I had kept up with Cajun French (AKA Louisiana French). I wish I hadn't let my cultural heritage fall through my fingers.

Many blessings to those who fought and lost their lives against the British colonists in an attempt to secure the freedom of not only themselves but of future generations to come.

[Disclaimer: I am still only beginning to educate myself about this event and am utilizing my current understanding of how events unfolded and who was involved. I apologize in advance for any misconceptions or misinformation regarding the historical accuracy of my comments.]

#Nova Scotia#France#Canada#Acadia#Acadian#Acadian Expulsion#Day of Commemoration#History#Family History#Family#Genealogy#Genealogy Blog#Twisting Tree#Twisting Tree Ancestry#Ancestry#Ancestry Blog#Cajun#Le Saint Remi#Day of Commemoration for the Acadian Expulsion#Guillot#Guillot Family#Louisiana#Louisiane#Acadie à la Louisiane#Acadie#Mi'kmaq#Mi'kmaw#French and Indian War#Pawpaw#Cajun French

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mira and a town of relatives

Mira and her father in the episode "The Great Diwali Mystery"

Mira, Royal Detective is one of my favorite series. I have to write about it here on this blog because unlike some other shows, the town where this Indian-inspired series is set, Jalpur, the protagonist, Mira, appears to be related to...everyone! This is like any small town. Anyway, I'd like to break it down for you all, because family ties and the value of family is central to this series, unlike any other that I have ever seen.

Reprinted from my Genealogy in Popular Culture WordPress blog. Originally published on June 2, 2021.

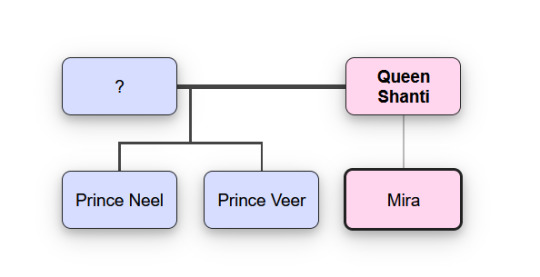

We do not currently know who Shanti's husband is, or if he is still alive. I created this using one of my favorite sites for creating family trees, Family Echo

Let's start with Mira, herself. She was appointed by Queen Shanti to be the royal detective in the city, and she considers her to be like a daughter. Shanti herself has two sons: Prince Neel, a brilliant and talented inventor, often flying around the city in his flycycle or some other invention, and Prince Veer, the aspiring King of Jalpur. Neel has a crush on Mira. We also know that he has a grand-grandmother who was an inventor and built a submarine, as shown in a recent episode, and has great aunt, Rupa. As for Mira, she has two friends, mongooses who help her out on cases: Mikku and Chikku. They are brothers and have two cousins, who are also mongooses: Preeti and Neeti, who are skilled in rope gymnastics. [1]

Mira, however, is NOT directly related to Queen Shanti. Her father is Sahil, who calls her "beti" when talking to her. Two of her friends, Priya and Meena, are sisters, and her cousins, as is Chotu, a younger brother of Priya and Meena (also known as Mina). Their mother is Pushpa, who is also Mira's aunt. Presumably, Kamala is also her cousin, who has a younger sister named Dimple. The same can, possibly, be said for her friends Pinky, Dhruv Sharma, and Sandeep. Apart from them are two brothers, Ranjeet and Manjeet, a music teacher (Sanjeev Joshi), who are her friends. [2] In a few episodes, the royal Nayapuram family appears, comprised of a king, queen, and their daughter, Princess Shivani.

In order to explain this, I came up with this chart created via one originally shared by Kathleen Brandt, a genealogist who wrote that it is "one of the biggest errors made when referencing cousin relationships."

So, we currently do not know the parents of Kamala and Dimple, Dhruv (whose surname is Sharma), Sandeep, or Pinky. But, it is possible that at least one of their parents is a brother or sister of Sahil and Pushpa. There are also many, many unnamed uncles that Mira meets in the town, meaning that they may be some of these people. Some of these parents may have been featured in some episodes but I'm not aware of them. That is definitely a possibility. Saying all of this, it is possible that Mira is calling older men she meets in Jalpur "Uncle" since, as some have noted, "kids routinely call complete strangers “Uncle” and “Aunty”" even if they aren't related. As Times of India noted in 2015, it is "very common" for those in India to call those older than themselves "Aunty" or "Uncle," with this done out of "respect for the elderly or for fellow humans." That could be the case here, even though the terms can also be used for those that someone is related to, by family ties.

Even so, I think that Pushpa is Mira's aunt, since her name in the show is literally "Auntie Pushpa." [3] In the end, I'll keep an eye on this series and possible write another post on this show later.

© 2021-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] In a recent episode, "The Case of the Vanishing Picnic," Mikku says "its not every day there are cousins that visit from the big city," referring to Neeti and Preeti, showing Mira secret family recipes they have prepared.

[2] This isn't accounting for the Palace Tailor, the two bandits (Manish and Poonam), Ram Sing Ji, and Deputy Oosha who are likely not related to Mira.

[3] In the episode "The Case of the Lost Treehouse," Mira's pa says "there's the tapestry your Auntie Pushpa made for the wall," making it clear this is the case.

© 2020-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#mira royal detective#indian culture#disney animation#disney#uncles#adopted daughter#adoption#genealogy#family history#family trees#roots work#aunts#reviews

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

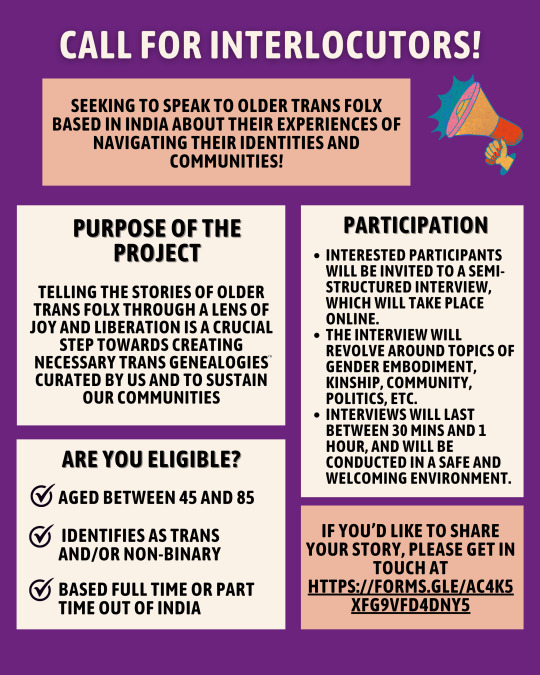

hi friends!

spreading the word about this really cool project. please also help get the work across to relevant folx!

0 notes

Text

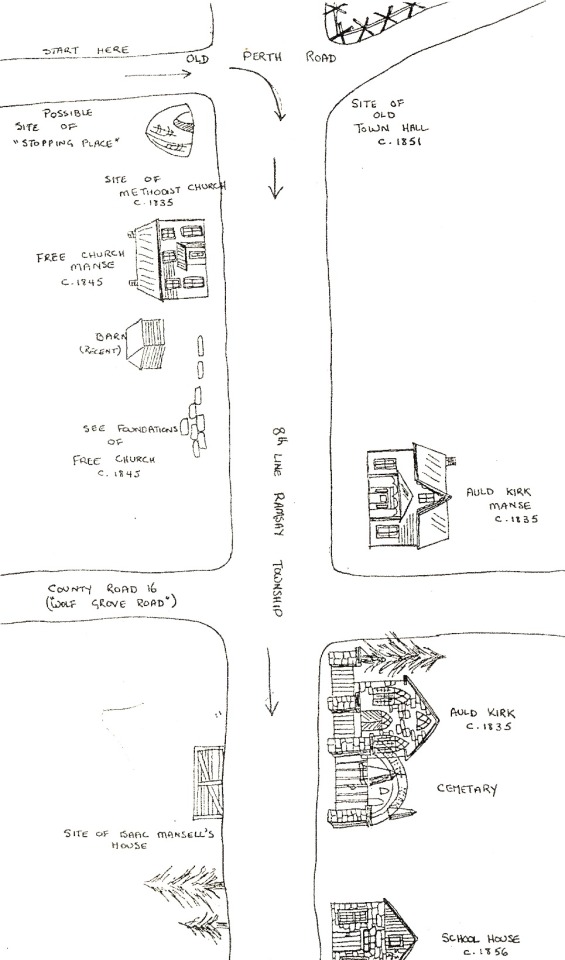

Memories of Leckie's Corners -- Linda More Dryer

Diagram from- The Importance of the Eighth Line–from Mississippi Mills

Linda More Dryer’s piece after reading- Dugald Campbell Memories of Ramsay Township and Almonte — Town Merchants etc.

Lovely article about the extra-ordinary folk of Ramsay and Almonte. Was just saying to someone at the Hub 50 th celebration that although there was the mill workers in Almonte, the significant of the farming…

View On WordPress

#8th line#almonte#Charles More#dugald campbell#genealogy#History#Indian Creek#Lanark-County#Leckies Corners#linda dryer#Mississippi mills#ontario#scottish#tannery

0 notes

Text

Feeling a bit down. The person who knows the most about my (our) Indian ancestors has said that they can’t be sure what region(s) they came from. Frustrating, as cultures and languages are so varied throughout India and I would’ve loved to know more.

There is the small possibility of finding out in the future; it would require access to some diaries that are in a museum library, which has been shut for a few years since an earthquake. I’ll hold out hope that we’ll find out some day.

0 notes

Text

जीएम सरसों पर प्रतिबंध से भारतीय किसानों को नुकसान सुप्रीम कोर्ट को विचारधारा के ऊपर विज्ञान को चुनना चाहिए | Indian farmers suffer from the GM mustard ban. The Supreme Court must favour science over dogma;

Source: theleaflet.in

पिछले दो दशकों से जीएम तकनीक पर पूर्ण प्रतिबंध लगाने पर जोर

सुप्रीम कोर्ट ने जीएम सरसों की रिहाई की मांग वाली अर्जी को स्वीकार करते हुए किसान संघ शेतकरी संगठन से पूछा, 'आप इतने साल कहां थे?'

जैसा कि सुप्रीम कोर्ट एक ऐसे मामले पर विचार-विमर्श कर रहा है जो भारत में आनुवंशिक रूप से संशोधित सरसों के भाग्य का निर्धारण कर सकता है, एक किसान निकाय भारत की शीर्ष अदालत में अपनी आवाज सुनने का प्रयास कर रहा है।

महाराष्ट्र स्थित किसान संघ, शेतकरी संगठन, सामाजिक रूप से संशोधित (जीएम) सरसों पर प्रतिबंध लगाने की मांग करने वाली कार्यकर्ता अरुणा रोड्रिग्स द्वारा दायर याचिका का विरोध कर रहा है। बीटी कपास के साथ अपने अनुभव के आधार पर, किसानों का तर्क है कि जीएम सरसों में खाद्य उत्पादन बढ़ाने और उनकी आजीविका में सुधार करने की क्षमता है।

भले ही उनके आवेदन को 17 नवंबर 2022 को रिकॉर्ड में ले लिया गया, लेकिन यह निराशाजनक है कि जिन किसानों की खेल में सबसे अधिक चमड़ी है, उन्हें अब तक सुप्रीम कोर्ट द्वारा नहीं सुना गया है।

जीएम सरसों की रिहाई की वकालत करने वाले आवेदन को स्वीकार करते हुए पीठ ने पूछा, 'आप इतने सालों में कहां थे?' यह सवाल जीएम की रिहाई के लिए और उसके खिलाफ लड़ने वालों के बीच संसाधनों और शक्ति में असमानता को ध्यान में रखने में विफल रहता है। सरसों।

कार्यकर्ता, अदालत का दरवाजा खटखटाने और अपना मामला बनाने के साधनों के साथ, पिछले दो दशकों से जीएम तकनीक पर पूर्ण प्रतिबंध लगाने पर जोर दे रहे हैं। इस बीच, जिन किसानों को बहुत अधिक लाभ होने वाला है, वे रोजी-रोटी कमाने के दैनिक संघर्ष में व्यस्त हैं। क्या प्रौद्योगिकी के उपयोग के माध्यम से एक बेहतर जीवन चुनने का किसान का अधिकार संसाधनों की कमी और कानूनी रास्ते तक पहुंच से बाधित होना चाहिए?

जीएम फसलों पर प्रतिबंध

पिछले 18 वर्षों से जीएम फसलों का व्यावसायिक उपयोग अधर में लटका हुआ है। 2002 में व्यावसायिक खेती के लिए पहली बार पेश किए जाने के बाद से ही ये फसलें भारत में बहस का एक विवादास्पद विषय रही हैं। अरुणा रोड्रिग्स और अन्य के साथ एक गैर सरकारी संगठन जीन कैंपेन ने 2004 में जीएम जीवों के उपयोग को चुनौती देते हुए एक जनहित याचिका दायर की थी। जीएम सरसों इनका ताजा शिकार है।

भारतीय वैज्ञानिकों द्वारा विकसित, जीएम सरसों में कृषि में क्रांति लाने और किसानों की आजीविका में सुधार करने की क्षमता है। हालांकि, कार्यकर्ताओं ने दावा किया है कि यह पर्यावरण और मानव स्वास्थ्य के लिए खतरा है। दूसरी ओर, किसानों का तर्क है कि प्रतिबंध कृषिविदों के लिए एक बड़ा झटका है और उन्हें अन्य देशों के किसानों की तुलना में नुकसान में डाल देगा जो पहले से ही जीएम तकनीक का उपयोग कर रहे हैं।

आजीविका में सुधार के अलावा, किसानों का मानना है कि जीएम तकनीक उन्हें बदलती जलवायु परिस्थितियों के अनुकूल बनाने, टिकाऊ कृषि को बढ़ावा देने और खाद्य सुरक्षा बढ़ाने में मदद कर सकती है। संगठन ने अपने आवेदन में शीर्ष अदालत से किसानों और कृषि उद्योग के लिए जीएम सरसों के लाभों पर विचार करने का आग्रह किया है। इस तरह की तकनीकों पर प्रतिबंध किसानों को और नुकसान पहुंचाएगा, खासकर भारत के शुष्क क्षेत्रों में, जहां पारंप���िक खेती के तरीके अपर्याप्त साबित हुए हैं। संगठन ने इस बात पर जोर दिया कि याचिकाकर्ताओं के अप्रमाणित और अंधविश्वासी विश्वासों के कारण किसानों को प्रौद्योगिकी का उपयोग करने से नहीं रोका जाना चाहिए। जीएम फसलें पैदावार बढ़ा सकती हैं और उत्पादन लागत कम कर सकती हैं, जिससे अधिक मुनाफा हो सकता है।......

#gm mustard#genetically#genetic genealogy#supreme court#GM mustard ban#indian farmers#indian farming#mustard farming

0 notes

Photo

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 1862

One hundred and sixty years ago the Hill family patriarch, James, died at the age of 99. He had witnessed life before the United States became a country, every president from George Washington to Abraham Lincoln, the ending of the French and Indian War to the start of the Civil War.

#family patriarch#history#George Washington#Abraham Lincoln#Civil War#French and Indian War#genealogy#family tree#America#colonies#British North America#Founding Fathers

1 note

·

View note

Note

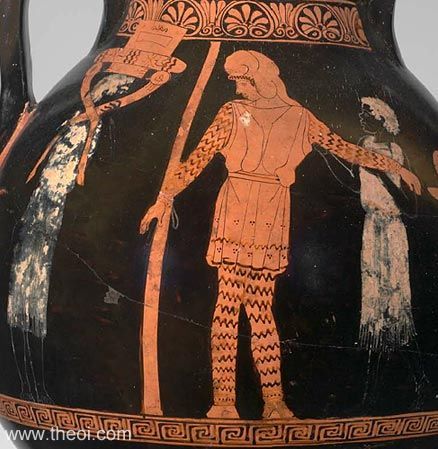

Hey quick question princess andromeda from the myth with Persus is from Ethiopia ? But then how come in paintings she is white ?

Quick question, long answer. Yes and no. It’s a little confusing. There are several parameters to this.

Aethiopia, an etymologically Greek name, is the name different Greeks gave to different places of the world. In the classical era (440 BCE), Herodotus called all the area south of the Sahara and the Nile as Aethiopia, making thus the most relevant description. Pindar however, a contemporary of his (~450 BCE), calls Aethiopia the region around Elam (Southwest Iran). Same as Hesiod, who did that in 700 BCE already. In ~500 BCE, both Scylax of Caryanda and Hecataeus of Miletus seem to agree Aethiopia is east of the Nile and expands throughout the Arabian peninsula all the way to the Indus Valley and the Indian Ocean. The first mention of Aethiopians is by Homer (~800 BC) who vaguely says that they lived in the extremities of the world, in the far east and west.

So as you see, the earlier back in time, the more generic and distant the term’s meaning is. Herodotus is likely the one who seals the association of Aethiopia with only sub-Saharan Africa and the country south of Egypt in particular.

The origins of Greek mythology precede all these writers. In general many historians suggest that the Aethiopia of the myth of Perseus and Andromeda was supposed to be in west Asia and perhaps somewhere around Israel and Palestine. Some believe it is Jaffa, Tel Aviv in particular. I am not totally sold on the explanations why. The point is however that Aethiopia’s geographical definition especially before Herodotus and even more before Hesiod was very vague and fluid. It seems it described places that in general were too hard for Greeks to reach, exotic.

The name itself can help us understand. Aethiopian means the one who looks burnt, smoked. From αίθω (aétho - burn) and όψη (ópsi - look, face). Now, this sounds low-key horrible in English but in Greek it’s not derogatory, but I have no better way to explain it. Ancient Greeks had written quite a few times about the attractiveness of the Aethiopians (whoever they were) so they didn’t associate the term with a repulsiveness like that of burnt flesh but just as the effect of the sun on their complexion.

In short, at least prior to Herodotus, Aethiopia was all the land inhabited by POC, even if that included large parts of Africa and Asia all the way to India. It did not include Libya (North Africa) and Egypt. This was not so much due to skintone (although it could be too - as North Africans can be way more white passing than people far from here believe) but because Greeks were well aware of these regions. Aethiopia was associated with exotic, distant places with darker people. This could be black people and brown people and all their various tones. Perhaps simply anyone who was noticeably darker than a Greek.

Now if we compare Jaffa (Andromeda’s Aethiopia) with modern day Israel or Palestine, then Andromeda and her parents could be medium brown or light brown or white / white passing.

However, I seriously doubt Ancient Greek art was concerned about skintone accuracy, simply because it was art made by Greeks and viewed by other Greeks. Everyone depicted usually followed the Greek standards of beauty. Besides, it’s a Greek myth, right? If we wonder about Andromeda’s complexion, then we should also wonder about her name! And her mother’s name! Why are they Greek? Well, simply, because it’s Greek mythology, which provides a genealogy where all progenitors are kin to Greek progenitors. Cepheus, Andromeda’s father, is brother of Danaus and has Argive ancestry (since this is a myth from Argos!). So if that’s true, Andromeda has Greek ancestry and might be white-passing because of that. But these is just exhaustive and in my opinion unnecessary nitpicking.

In Ancient Greek art complexion is almost always not depicted accurately but men are usually depicted as dark and women as fair because this was the beauty standard.

No this doesn’t mean Perseus was black and Andromeda white! It only shows the beauty standards of the time. Corinthian vase. Archaic period.

Andromeda, Perseus and Cepheus. Apulian vase, Classical Period. All look white or white passing.

Here although the skintone is the same, the artist makes Perseus blonde in order to stress Andromeda’s darkness through the haircolour. Zeugma, Roman period.

And… look at that!

In this ‘mildly’ racist art, Andromeda is depicted as a dude as the tall white-passing person in the middle and she is getting tied for the beast by fellow Aethiopians who however look nothing like her. They are shorter and clearly African. Andromeda wears Phrygian, thus non-African clothing, but also nothing like the Greek clothing. This artist wanted to provide some diversity but apparently not for the beautiful princess lol Attic vase, probably Classical period.

Anyway so, Andromeda was either brown or black or white passing at most, because of Jaffa and the argive ancestry. Once Aethiopia - Ethiopia’s location had become more specific though, western artists depicting Andromeda as pretty fair of skin or blonde is misrepresentation with questionable motives. My opinion is that there is a wide range of looks Andromeda can be depicted to have, but not something that makes her look whiter or even just as white as Perseus.

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]he political philosophy underlying Westphalian, modern sovereignty [...], foundations of the modern state, [...] [formed] in relation to plantations. [...] [P]lantations [are] [...] laboratories to bring together environmental and labor dimensions [...], through racialized and coerced labor. [...] [T]he planters and managers who engineered the ordering and disciplining of these [...] [ecological] worlds also sustained [...] [p]lantations [by] [...] disciplining (and policing the boundaries of) humans and “nature” [...]. The durability and extensibility of plantations, as the central locus of antiblack violence and death, have been tracked most especially in the contemporary United States’ prison archipelago and segregated urban areas [...], [including] “skewed life chances, limited access to health [...], premature death, incarceration [...]”. [...]

Relations of dependence between planters and their laborers, sustained by a moral tie that indefinitely indebts the laborers to their master, are the main mechanisms reproducing the plantation system long after the abolition of slavery, and even after the cessation of monocrop cultivation.

The estate hierarchy survives in post-plantation subjectivities, being a major blueprint of socialization into work for generations and up to the present. [...] [Contemporary labor still involves] the policing of [...] activities, mobility and access to citizenship [...].

---

[There is] persistence - until the 1970s in most Caribbean and Indian-Ocean plantation societies, and even until today in Indian tea plantations [...] - of a system of remuneration based on subsistence wages [...]. Plantations have been viewed as displaying sovereign-like features of control and violence monopoly over land and subjects, through force as much as ideology [...]. [W]itness the plethora of references to “plantocracies” [...] ([...] sometimes re-christened “saccharocracies” in the Cuban and wider Caribbean context [...] [or] “sovereign sugar” in Hawai’i). [...]

[T]race the genealogy of contemporary sovereign institutions of terror, discipline and segregation starting from early modern plantation systems - just as genealogies of labor management and the broader organization of production [...] have been traced [...] linking different features of plantations to later economic enterprises, such as factories [...] or diamond mines [...] [,] chartered companies, free ports, dependencies, trusteeships - understood as "quasi-sovereign" forms [...].

---

[I]n fact, the relationships and arrangements obtaining in the space of the plantation may be analogous to, mirrors or pre-figurations of, or substitutes for the power and grip of the modern state as the locus of legitimate sovereignty. [...] [T]he paternalistic and violent relations obtaining in the heyday of different plantations (in the United States and Brazil [...]) appear as the building block and the mirror of national-imperial sovereignties. [...]

[I]n the eighteenth-century [United States] context [...], the founding fathers of the nascent liberal democracy were at the same time prominent planters [...]. Planters’ preoccupations with their reputation, as a mirror of their overseers’ alleged skills and moral virtue, can thus be read as a metonymy or index of their alleged qualities as state leaders. Across public and private management, paternalism in this context appears as a core feature of statehood [...]. Similarly, [...] in the nineteenth century plantations were the foundation of the newly independent Brazilian empire. [...] [I]n the case of Hawai’i [...], the mid-nineteenth-century institution of fee-title property and contract labor, facilitated by the concomitant establishment of common-law courts (later administered by the planter elite), paved the way to the establishment of sugar plantations on the archipelago [...].

---

[T]he control of movement, foundational to modern sovereign claims, has in the plantation one of its original experimental grounds: [...] the demand for plantation labor in the wake of slavery abolition in the British colonies (1834) occasion[ed] the birth of the indenture system as the origin of sovereign control on mobility, pointing to the colonial genealogy of the modern state [...].

The regulation of slaves’ mobility also represented a laboratory for the generalization of [refugee, immigrant, labor] migration regulation in subsequent epochs [up to and including today] [...] [subjugating] generally racialized and criminalized subjects [...]. [P]lantations appear as a sovereign-making machine, a workshop in (or against) which tools of both domination and resistance are forged [...].

---

All text above by: Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. "Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times". Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives (edited by Petitcrops, Macedo, and Peano). Published 2023. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for criticism, teaching, commentary purposes.]

#abolition#ecology#multispecies#landscape#imperial#indigenous#colonial#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#plantations#ecologies#carceral geography#caribbean

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#imeuswe#indian family history#indianfamily#indian genealogy#indian family genealogy#indian family stories#genealogical indian record collections#indian ancestry#familytree

1 note

·

View note

Text

NO! You are NOT Cherokee!

History of the biggest myth in genealogy!

youtube

liars Really hate DNA and records.

#Youtube#Cherokee Freedmen#white indians#indian lies#genealogy#Freedmen#Cherokee Black Indians#Black Indians#Dawes Rolls#Dawes Act#dawes#citizenship rights#tribal lies

0 notes

Text

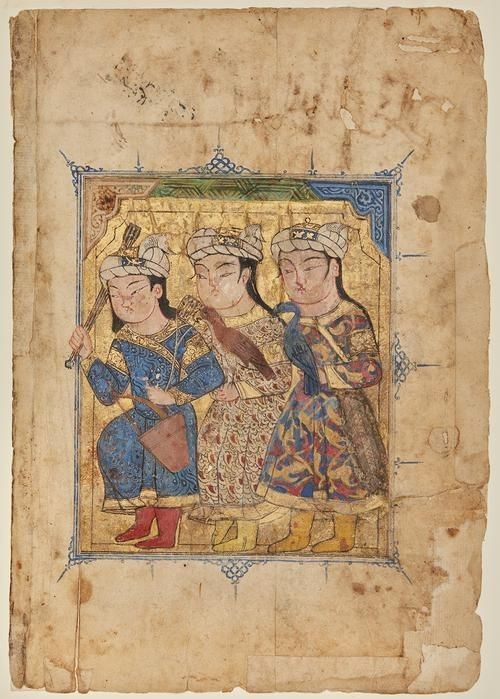

Talking about the Qabā'. Again.

The last time I talked about the Qaba was in another post where i was very excited to have found a miniature from either Syria or Egypt that matched an extant piece of fabric from a close time period. Today I'm going to talk about the garment itself more, and it's relatives. The impetus for this is that a few months ago, I was scrolling through hanfu blogs- if you've read the article I published in Egyptian Migrations, you know I have an interest not just in Egyptian fashion, but how other cultures navigate fashion, both in their unique subcultures and traditional styles. While doing so I came across the tieli (貼裏), and quite liked the look of it, so I searched up the garment and began looking more at it. As I was scrolling through the many pretty pictures, I realized hey- I've seen this before. This looks a lot like that coat with the red foliage pattern!

Turns out this was because they're related.

They're not the only ones either- the Qabā' (as both Farsi and Arabic call it), the Tieli, the Indian Jama, the Korean Cheolik, and more, all bear a resemblance to each other. Covergent evolution happens plenty of course, but in this case there's something of an established link. In fact while doing my research, I found a paper specifically about this garment family (The Dress of the Mongol Empire: Genealogy And Diaspora of the Terlig by Woohyun Cho, Jaeyoon Yi, and Jinyoung Kim), though without explicit mention of the Qabā'.

The name and garment Tieli come from the Mongolian Terlig and Jisün (also called a Zhama (诈玛 or 詐馬), establishing a possible linguistic connection to the Jama) during the Yuan dynasty. Like many Mongolian traditional garments, it's well suited to horseback riding, which which what many Mamluk depictions also show the Qabā' being worn during. It could be round or cross collar (the combination of the two is unique to the Qabā'). The key features of the garment were a knee to calf length skirt that was gathered or pleated, a close fitting bodice cut separate from the skirt, close fitting sleeves, a corded waist which usually lead into the ties that closed the garment. According to the aforementioned trio, the garment was originally made of hides, and the waist detail found in the original Terlig, lost in other cultures renditions, is an indication of this. The Terlig, known before this point, was introduced to China, India, and Korean when the Monglian Empire was an active political entity in the 13th century and onwards, and this is the case for this style of Qabā' as well. During the 13th century, the Ilkhanate was established in the former territory of the Khwarazmian Empire, after a political incident where the Shah ordered the execution of a group of merchants sent by the Mongolian Empire lead to a long military conflict. The Ilkhanate went on to control large portions of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and the Caucasus, as well as Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Pakistan. Ultimately the Ilkhanate tried, but never did, conquer Egypt, which was ruled by the Mamluks at the time.

However, it did leave a cultural influence behind. Reference to this origin for this style of qaba can be found in one of the two names for the Qabā': al-aqbiya al-tatariyya or qabā' tatarī, meaning the Tatar coat or Tatar way of wearing a coat. Tatar, in this instance, is being used to refer to Mongolians. A similar distinction can be found in the Jama, where Muslims fasten it on the right in the Mongolian style (brought to my attention by the paper mentioned before). The tatarī is fastened in the same way, ties on the wearer's right of the body. The other style of Qabā' (al-aqbiya al-turkiyya) is the same, but fastens on the opposite side of the body. The Mamluks preferred the tatarī, but it was not the exclusive style worn. Along with this, some Qabā' fastened in the center front.

The Jisün was a type of Terlig, made of one color of silk and gold, worn as a robe of honor by officials during the Yuan dynasty. During the later Ming dynasty, it became the dress of certain military officials. It had different varieties for seasons and social status. It also progenitated the Yesa (曳撒), which was longer and more widely worn than the Jisün. The Feiyufu (飞鱼服) was a Ming variant of the Tieli, and another type of honor robe. The Qing dynasty Chaofu also seems to have taken the terlig into account when it was designed.

The Cheolik has a crossover collar, pleated skirt, and may have quite long, wide sleeves. Political marriages with Mongolian courts likely helped this garment take root. This garment is still worn today as Korea, like China, has revitalized its traditional clothing. It is mostly by women today as far as I can tell, though historically it was a masculine garment. It has a longer hem than the Terlig. It also sometimes had a higher waistline.

The Jama was introduced by the Mughal dynasty, and unlike the other garments listed here which typically used rectangles and triangles for constructing clothes, the one pattern I've seen for it taken from an extant garment (as opposed to being a guess) shows a skirt made of gores and set in sleeves with a gusset. Another example, laid flat, shows rectangular sleeves with a gusset, but the skirt cannot be determined. It was later renamed to sarbgati. It typically has a crossover fastening, though I have seen one that closed in the center front. The ties are especially prominent and decorated, which overall is not the case in the rest of the garment family. Gold bands on the sleeves and collar are sometimes found as decoration. It also has a longer hem and higher waistline than the Terlig.

In my previous post I noted a similarly to this robe and the Central Asian and Persian robes I'd seen from a different century, but was hesitant to connect them. Now I'm sure of a connection. The waist seam is confirmed! There are still several stylistic differences, though:

1. The Qabā', in Syrian and Egyptian depictions, typically combines a round neckline with the cross over collar. The Persian Qabā' typically does not have a round neckline.

2. The Qabā' usually has what looks like a gathered skirt, not a pleated one, as the Tieli does. The Terlig sometimes has a gathered skirt as well, as does the Jama.

3. The Syrian and Egyptian Qabā' is decorated with strips of gold, not with a cloud collar. The Persian Qabā' often has a cloud collar, which it inherits from the Terlig, and I have seen an Angarkha from Lahore with a cloud collar as well. It sometimes has bands. The Seljuk Qabā' sometimes has bands, and sometimes has a rank badge (more commonly found in Chinese court dress). As an aside, I recently found a British drawing (from life, presumably) of an Egyptian envoy in a garment similar to an Angarkha as well...

4. The Qabā' in Syrian and Egyptian depictions often retains the knee or calf length good for horse riding that many other garments in this family moved away from.

5. The Qabā' most likely does not have the corded waist found in the Terlig. There is a gold band around the waist in some depictions that could be a braided waist, but could also be a belt. Unfortunately I don't know of any extant examples from Syria or Egypt that would clarify matters. There is an example which might be Persian that does show this corded waist. Most depictions have no waist detail other than an indication of a waistline.

As far as I know, while this robe spread a little into the Balkans and Eastern Europe (the cloud collar has appeared in some Christian Iconography and a few examples of Terlig like historical garments exist), it did not spread much further west or south of Egypt. However, given the Qabā' has been excluded from discussions of the Terlig's many sons already, it's possible I simply don't know about it, as further iterations in Africa would be excluded as well. As always, I welcome people bringing their own findings to the table.

Further reading: The Dress of the Mongol Empire: Genealogy And Diaspora of the Terlig by Woohyun Cho, Jaeyoon Yi, and Jinyoung Kim

Mongol court dress, identity formation, and global exchange by Eiren L. Shea

https://sartorialegypt.wordpress.com/2022/12/03/a-brief-discussion-of-a-mamluk-robe/ - prev post

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O480307/gown/ - the cloud collar angarkha

https://www.newhanfu.com/6021.html - Discussion of the tieli and yesa

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41917645 - Terlig discussion

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43957434 - general discussion of Yuan clothing with a nice example of a terlig

https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/silk-road-themes/mouvable-heritage-and-museums/robe-decorative-braided-waist-band-0 - Terlig example

A Preliminary Study of Mongol Costumes in the Ming Dynasty by Luo Wei

https://m.terms.naver.com/entry.naver?cid=46671&docId=563301&categoryId=46671 - Cheolik

Arab dress: a short history; from the dawn of Islam to modern times by Yedida Stillman

https://lugatism.com/outer-garments-in-the-mamluk-sultanate/#3-_Qaba_qba - the Qaba and other dress in the Mamluk era

https://www.agakhanmuseum.org/collection/artifact/robe-AKM677 - a robe which may be Persian or Central Asian with the corded waist

Additionally, blogs like @ziseviolet and @fouryearsofshades post about hanfu, including the tieli and yesa.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“A deep psychosis inherent in US settler colonialism is revealed in settler self-indigenization.

The phenomenon is not the same as the practice of “playing Indian,” which historian Philip Deloria brilliantly dissected, from the Boston Tea Party Indians to hobbyists dressing up like Indians to New Age Indians. Settler self-indigenization’s genealogy can be traced to the period of the mid-1820s to 1840s, what historians call the Age of Jacksonian Democracy, marked by, among other phenomenon, the blossoming of US American literature.

The giants of the era are well known to every US high schooler who has had to suffer through American Lit classes—Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman, Longfellow, Hawthorne, and dozens of others. Among them was James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851), who conjured the United States’ origin story in his Leatherstocking Tales, made up of five novels featuring the hero Natty Bumppo, also called variously, depending on his age, Leatherstocking, Pathfinder, Deer-slayer, Hawkeye. Together the novels narrate the mythical forging of the new country from the 1754–1763 French and Indian War to independence to the settlement of the plains by migrants traveling by wagon train from Tennessee. At the end of the saga, Bumppo dies a very old man on the edge of the Rocky Mountains as he gazes east. But it is The Last of the Mohicans, subtitled A Narrative of 1757, that relates the self-indigenization myth that has endured. The Last of the Mohicans was a best-selling book throughout the nineteenth century and has been in print continuously since, along with a half dozen Hollywood movies, the first in 1911, plus several television series made in the US, Canada, and Britain. The most recent Hollywood production was a blockbuster that appeared in 1992, the Columbus Quincentenary.

Cooper conjured the birth of something new and wondrous, literally, the US American race, a new people born of the merger of the best of both worlds, the Native and the European, not a biological merger but something more ephemeral involving the disappearance of the Indian. Cooper has Chingachgook, the last of the “noble” and “pure” Natives, die off as nature would have it, handing the continent over to Hawkeye, the indigenized settler and Chingachgook’s adopted son. The publication arc of the Leatherstocking Tales parallels the Jackson presidency. For those who consumed the books in that period and throughout the nineteenth century—generations of young white men mainly—the novels became perceived fact, not fiction, and the basis for the coalescence of US American settler nationalism, the settler ideology that justified the fiscal-military state.”]

roxanne dunbar-ortiz, from not a nation of immigrants: settler colonialism, white supremacy, and a history of erasure and exclusion, 2021

#roxanne dunbar ortiz#lesbian literature#history stuff#cw genocide#essential for understanding American literature and ESPECIALLY American fantasy literature

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

edgar rice burroughs’ “a princess of mars” is so entrenched in the planetary romance and sword and sorcery genres that it forms a foundation stone of, as well as in the specific styles and bigotry of the first decades of the 20th century that there was little in it that i haven’t seen before, but there are two things that were noteworthy to me. firstly, the book clearly demonstrates that, in the fin de siecle white american literary imagination, the figure of the honorable southern gentleman of the confederate army was unquestioned as the latest link in a chain of chivalric heroes including cowboys, swashbucklers, and arthurian knights. secondly, the book follows much early-century science fiction into directly mapping the narrative of a method of white colonial expansion onto its protagonist’s interaction with an alien world—as a trip to the moon (1902) invokes direct colonial conquest and c.s. lewis’s space trilogy invokes missionary work, so this book invokes manifest destiny and “cowboys and indians” narratives—and it also follows the vast majority of science fiction in its orientalism, providing an almost textbook recreation of the narrative of an exotic, brutish people living in the ruins of greatness created by ancestors who have much more kinship to white people than they do to their own descendants. however, interestingly, this book frames the degeneration of the martians and particularly of the green men as the direct and explicit product of eugenics. i do not know enough about edgar rice burroughs to know his wider stance on the issue, but it does seem a striking stance to take in 1911, when eugenics was a darling of the scientific and popular community of europe and america. other than these two things, there wasn’t much of interest and import in the book, but it does contribute to several significant literary genealogies of modern science fiction and fantasy

#am i glad i read it?#well i’m glad i won’t have to read it again#and it was interesting to see the racist/orientalist associations of many sff tropes set out in open and unabashed terms#but i don’t think i would recommend it#ryddles

31 notes

·

View notes