#i will interpret him as a narcissistic lunatic all i want because it makes sense

Text

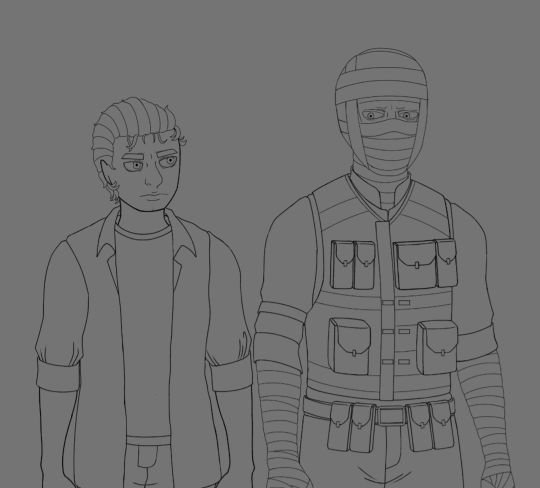

Also from the same thing-some line art featuring my Courier/former legionary, Cadmus, and Joshua Graham

To say they dislike each other would be an understatement

For context, I write Joshua as being more unhinged in my canon, hidden under a very thin veneer of religious zealotry-even the sanest of people don't remain 'normal' after 30 odd years of committing the most vile of crimes, and IMO, he's still the Legate under all that

#fallout#fallout new vegas#fnv#digital art#my art#wip#joshua graham#courier six#oc: cadmus#also don't @ me about joshua#i will interpret him as a narcissistic lunatic all i want because it makes sense

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Vindication of Venom Part 12: Appendix and Conclusion

Part 11

There were numerous side points I wished to make in the main parts of this essay series. However since they would have derailed my central arguments or else didn’t really address the central questions I proposed I cut them. But I didn’t want to simply throw them away or present them altogether out of context for this series.

As such I’ve included them below alongside my conclusion to this series.

Power Trip

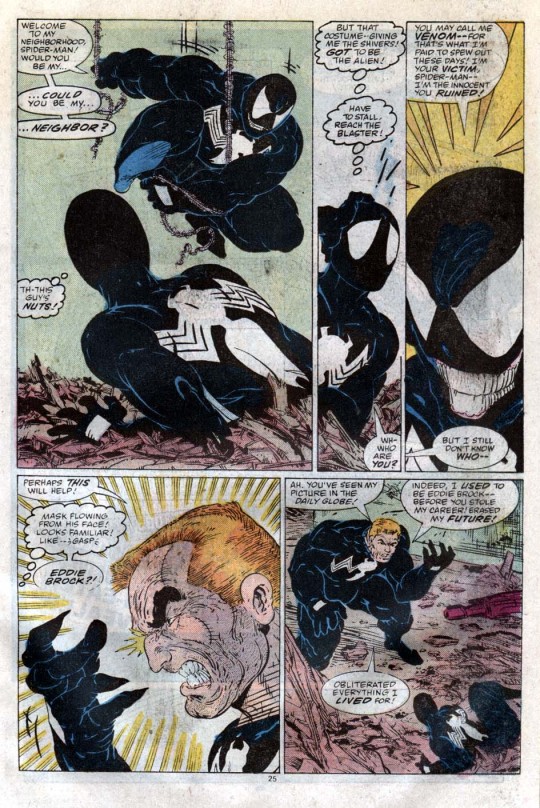

An important aspect to consider in Brock’s portrayal in ASM #300 is his callousness and general attitude towards violence.

When it comes to violent acts (or even just the prospect of them) Brock reacts with humorous, delight or at times nonchalance.

I’m not suggesting Brock was always like this as evidence of him always being a twisted person. Rather I think he developed these approaches towards violence from a few potential places.

The easiest explanation for it would be that his actions and attitudes are all part and parcel of his continued delusional state. He’s so out of touch with reality he no longer can perceive the horror or immorality of his violent acts.

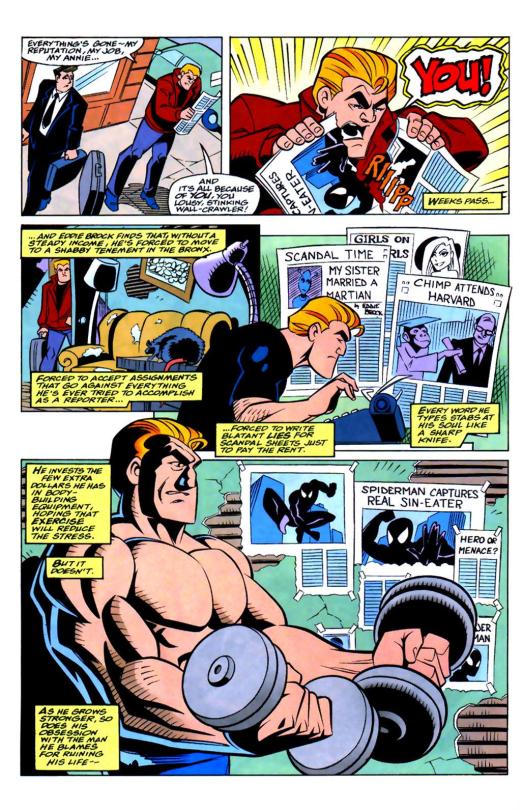

Potentially his attitude is an outgrowth of his long-term furious workout regime where he visualized himself performing violent acts on Spider-Man over and over again as he obsessively exercised.

Visualization can have a powerful effect upon one’s actions and mind, especially when done repeatedly and with such fervour as in Brock’s case. Remember he was also looking at pictures of the person he hated to motivate him.

However I’d suggest the more likely (or most prominent) explanation is that upon bonding with the symbiote Brock went on a massive power. As an extension of this his own delusions and his desire for revenge would’ve been further fuelled through the acquisition of raw, tangible physical power. Such an experience also wouldn’t have helped if Brock were already somewhat narcissistic (see his proclamations of his journalistic skills and respect).

After all, many of Spider-Man’s villains have had their egos explode once they acquired super powers. Doctor Octopus is a prime example if one were to re-read Amazing Spider-Man #3.

Whilst Doc Ock might be excused on the grounds that his origin was created in the 1960s, in 2000 story ‘Revenge of the Green Goblin’Norman Osborn’s origin was recounted and telling the readers that he felt himself above mortal men by virtue of his newfound super strength.

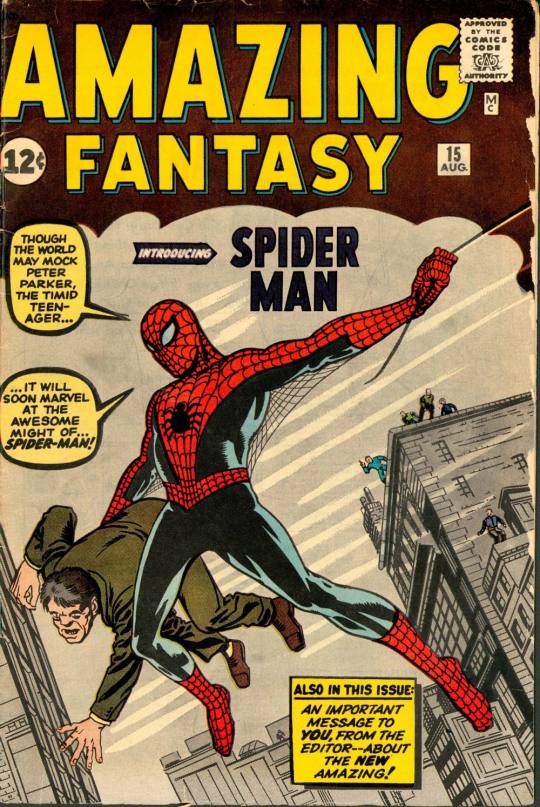

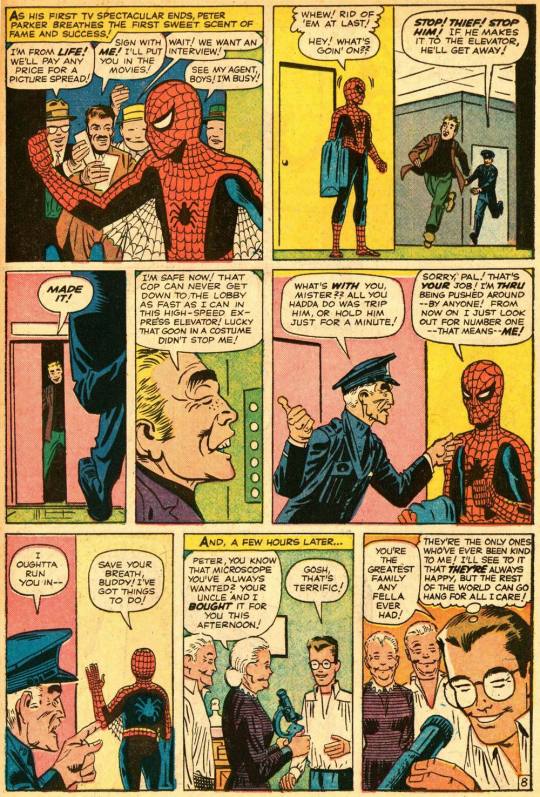

In fact Spider-Man himself goes on, if not a power trip, then at least a radical inflation of his ego upon gaining his own powers. He talks about how much better the powers now make him and how above the mockery of his peers or petty concerns for other he is. This is even featured on the cover of his first appearance.

To an extent one might argue that such a power trip is natural for most human beings. Indeed having superior physical power is a dream and desire engrained into the collective consciousness of all mankind. It is a very big reason why we have mythic figures such as Heracles, Sampson and even our modern day superheroes. And those with power (physical or otherwise) often times feel it entitles them to assert their wills and dominate others simply because they have the means to do so. Might makes right.

Power trips can prove particularly poignant for individuals who’ve lived with a sense of helplessness/powerlessness in some way in their lives (especially if their new power is physical in nature). Such people who obtain power will almost inevitably see their egos inflated and this could include a presumption in (and further entrenching of) their own righteousness. Part of that could involve a tweaking of the facts (or their perception of them) to suit themselves.

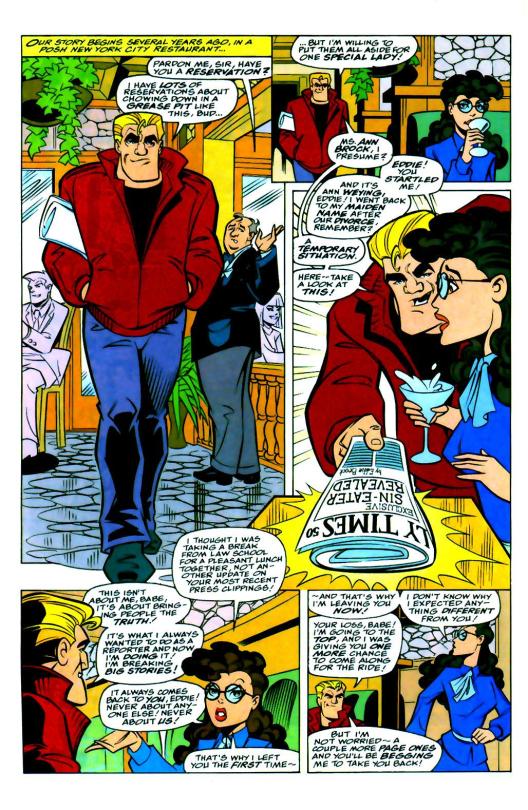

In the wake of the Sin Eater scandal, Brock had lost his career. He’d lost the degree of ‘power’ he could assert as a journalist. He was forced to seek out work from writing drivel he found repugnant and demeaning. He lived in a run down area. And to him all this happened because some asshole butted into something that wasn’t his business. And that person was nothing less than some anonymous, inhuman ‘hero’ with powers beyond mere mortals like Brock (meaning he had little hope of exacting retribution). Eventually he was in such despair he was seriously considering ending his own life. Under these circumstances I think it’s safe to say he felt incredibly powerless.

So when the symbiote came along and abruptly handed him immense power, power in fact similar yet greater than the person he blamed for his woes, inevitably there was going to be an adverse affect upon his mind, his actions and his very perception of himself and his life.

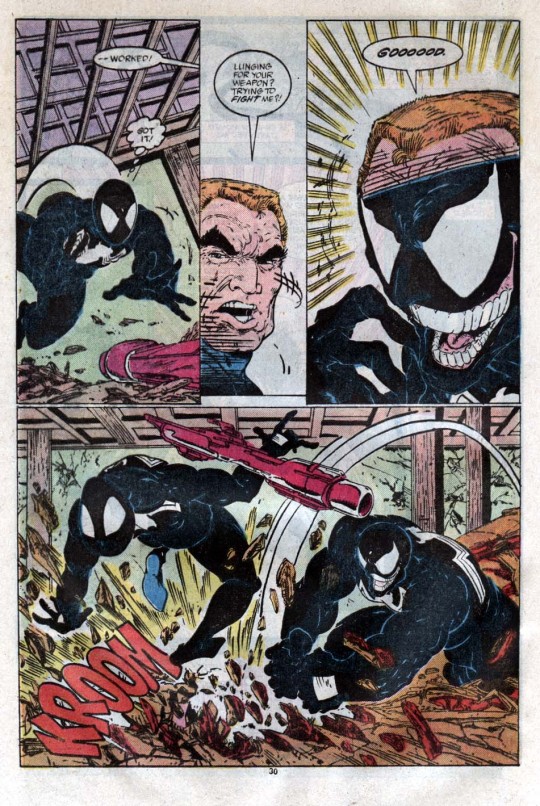

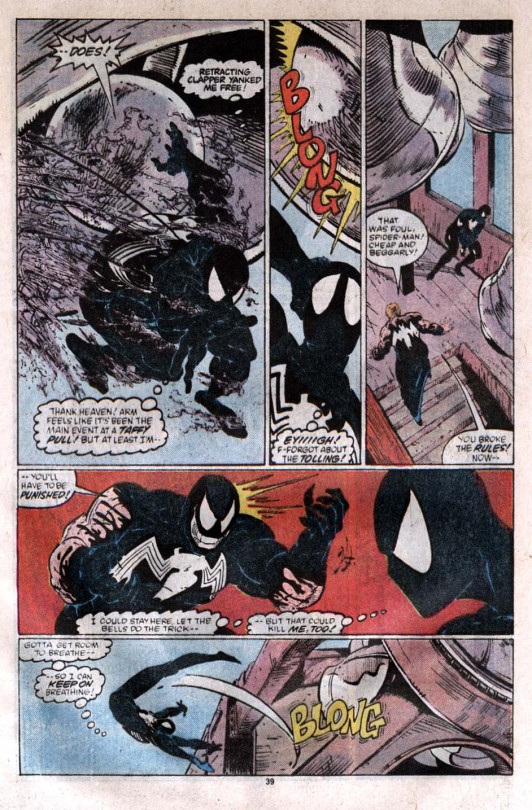

The raw physical power the symbiote lent him gave him free reign to his violent inhibitions. Brock likely he felt that the usual constraints of society no longer applied to him, hence not only his violent actions as an outlet for his rage but his casualness, joy and twisted humour in relation to those acts. When it comes to Spider-Man he was also handed another form of power, knowledge of his secret identity and the power to render Spidey’s greatest defence utterly useless, both of which (as far as he knew) were profoundly unique to him. The idea that the very act of gaining this immense power affected his mind is hinted at in ASM #300.

After being handed the means to free himself from his wretched existence and make his fantasies reality Brock became akin to a kid in a car on their way to Disney land. Excited and delighted at the prospect of getting to make their dreams come true. This is rather nicely reflected in the second Venom story, specifically the climax in ASM #317.

On the other hand his humour could’ve been a by-product of his experience as a writer where he might have needed to be witty or funny at times. Or maybe he just had a particular dark sense of humour.

However I think it makes much more sense that his attitude towards violence is more poignantly tied to what I discussed above. In his mind the rules of regular society and ‘lesser people’ (i.e. weaker non-super powered people) no longer apply to him. His power (and his ‘suffering’) puts him above all that, so it doesn’t matter if some people get hurt along the road to his personal gratification; he is justified.

Furthermore you could also argue that his constant visualization of Spider-Man’s violent death likely desensitized him to the idea of violence to some extent.

Echo Chamber

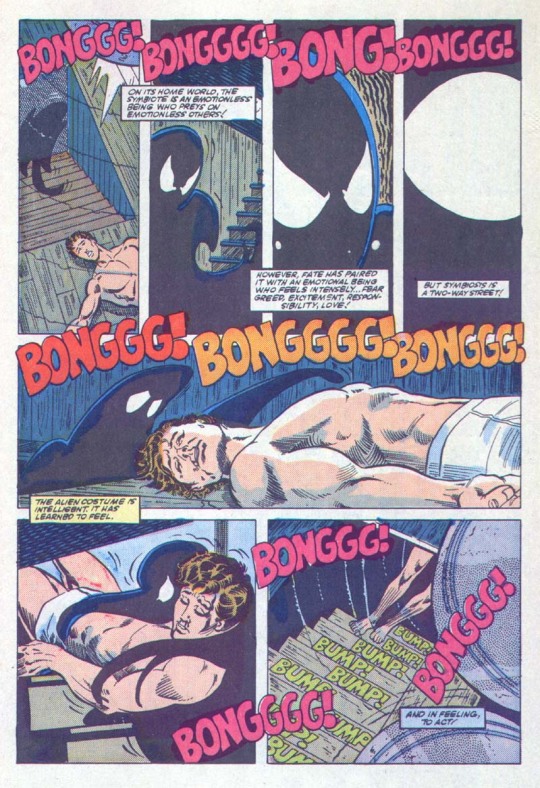

In Web of Spider-Man #1 we learn that the processes of symbiosis cuts both ways meaning the symbiote could itself be influenced by it’s host.

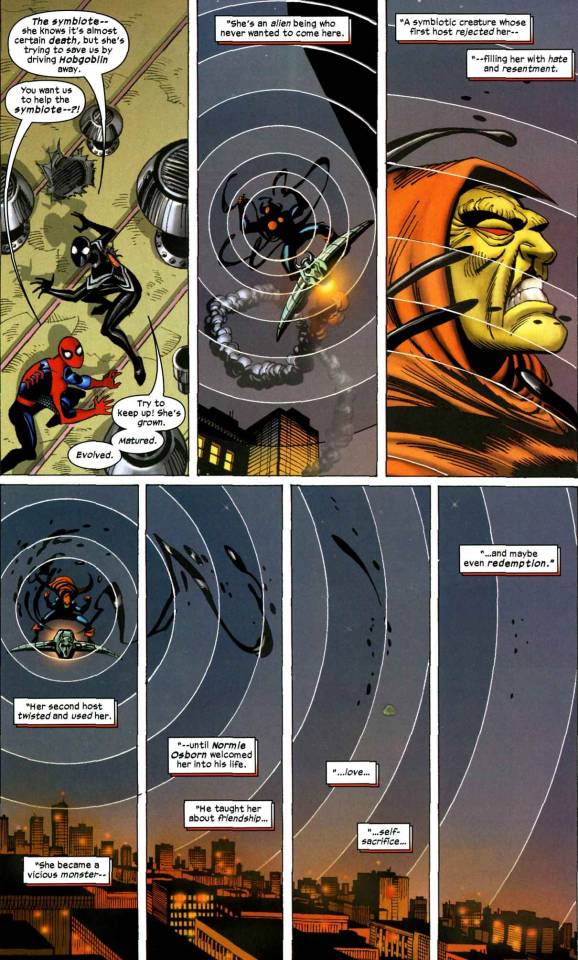

For what it is worth this is somewhat corroborated in Spider-Girl #100.

Though Spider-Girl exists in a different universe from the mainstream 616 version of Spider-Man it had an identical history to the 616 Marvel Universe up until about the stories published in 1998. The series was also shaped mostly by veteran Spider-Man writer/editor Tom DeFalco, who is recognized as an authority on Spider-Man if there ever was one. DeFalco actually penned ‘Spider-Man: the Ultimate Guide’ back in 2001, at the time the most definitive Spider-Man information book ever.

Spider-Girl #100 was itself not only worked on by DeFalco but also Ron Frenz who along with DeFalco actually introduced and explained the symbiote’s origins back in the 1980s.

However yet more corroborative evidence is provided in Brian Michael Bendis’ run of Guardians of the Galaxy as well as Robbie Thompson’s run on Venom: Space Knight, both of which assert that the symbiote was ‘corrupted’ through exposure to it’s hosts, something common to it’s species.

This can go some way to explaining the symbiote’s hatred Spider-Man despite it also caring about him and attempting to save him in Web #1. It was influenced by Brock’s own hatred of the wall-crawler.

However since ‘symbiosis is a two-way street’ and we see clearly Brock talking to the symbiote in ASM #300 it is possible Brock could’ve ‘felt’ the symbiote’s hatred for Spider-Man. This then could have validated Brock’s own hatred for Spidey and caused him to double down on his warped interpretation of events.

If you accept that Brock and the symbiote could to some extent influence one another, this could then be said to have created a kind of echo chamber, or rather an ‘amplifier chamber’.

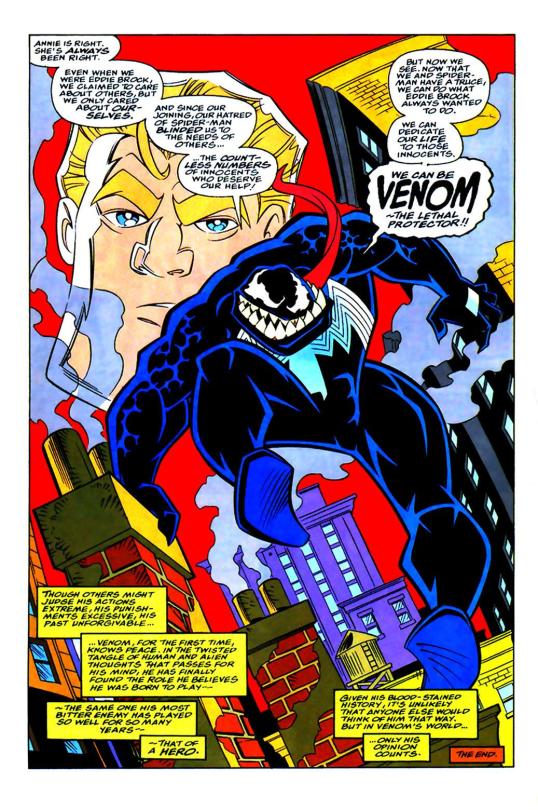

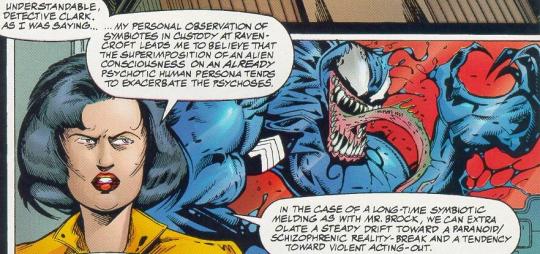

That is to say Brock’s hatred for Spider-Man causes the symbiote to hate him more. Then the symbiote reflects those increased feelings of hatred back onto Brock. This would then magnify Brock’s hatred for Spidey and he’d reflect that back onto the symbiote, and the cycle would begin again. The end result would be both individuals have their hatred amplified and their rationales for said hatred continually validated. These notions were also implied in the above image.

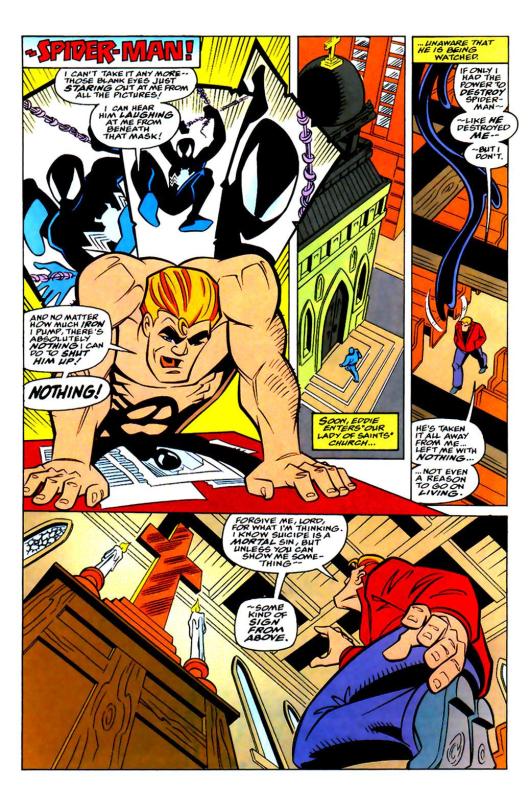

Role of Religion

Eddie Brock’s religious beliefs cannot be dismissed when analysing the character.

To begin with he was a man in despair when he encountered the symbiote. He was considering suicide and though he couldn’t go through with it, he was still in a state of helplessness. The symbiote’s arrival must have seemed to be a kind of miracle to him. He even talks about their meeting using religious language.

He was a man of faith in his darkest hour praying for help in a holy place when and then from above him the answer to his prayers appears. He gets a constant, affectionate companion who shares his deepest darkest desire and gives him all the means he could ever need to fulfil it.

For a desperate religious person how could Brock not see this as a sign from God that his feelings and vengeance is righteous?

Of course in reality his use of this newfound power is utterly contrary to the faith he holds as so important. Conceptually not only does this hammer home the hypocrisy of the character but also highlights his insanity, coding him as a ‘religious lunatic’ type of character.

In a sense Brock is representative of numerous individuals throughout history who act upon religious beliefs and use them as justification for their actions despite ignoring other core tenants of said religion. The Ku Klux Klan, the Westboro Baptist Church, the Spanish Inquisition, the Knights Templar, Al-Qaeda and ISIS are just some of the many examples of groups of individuals like this throughout history.

As mentioned in Part 8, the most illustrative example of Brock adhering to this archetype is his inability to kill himself due to his religion despite his willingness to take the lives of others. However there are other examples to be found in ASM #300.

The time period of the issue’s publication is important to these notions too. Remember this is the late 1980s.

In America during the late 1970s/early 1980s there had been something of a resurgence in traditionalist religion and with it of course a certain degree of religious zeal to accompany it. More poignantly you saw the mainstreaming of tele-evangalism, moral panics about the stuff that the kids were into and things along those lines.

This accompanied of course a certain peaked interest in the occult. These elements being part of the early-mid 1980s pop culture is what led to products such as Ghostbusters and the X-Men graphic novel God Loves Man Kills to be produced.

Though the embers of that had died down when ASM #300 was published in 1988 it was still there, as evidenced by the X-Men crossover Inferno in 1989 centred around the idea of a demonic invasion of New York city.

In this context the religious aspects of Brock’s character and how they are conveyed act as shorthand to the readers that Brock is ‘a religious lunatic’. As times changed perhaps that shorthand became less prevalent to consequent readers. However it is still patently obvious.

Dark Reflections

I stand by my statements from Part 3 that Michelinie’s primary conception of Venom did not involve him being a ‘dark reflection’ of Spider-Man. However by accident or design the character’s debut does grant him some traits that render him along these lines.

To begin with he obviously possesses Spider-Man’s powers, uses them for evil and does so whilst wearing a villainous version of Spider-Man’s costume that also has a darker colour palette. The basic ‘dark reflection’ villain starter kit.

Beyond this though Venom’s physicality and fighting style is different to Spidey’s. Peter is a muscular man with a lean build who uses his powers in combination with his intelligence (leading with the latter) to win battles. Brock by contrast has a bulky body build and relies upon overwhelming his opponents with his superior physical power to win battles, though he isn’t honestly stupid.

However where Venom is truly a dark reflection of Spider-Man is in contrasting their respective origins and motivations.

Brock is a foolish, immoral and possibly selfish actions in letting a dangerous individual roam free ruined his career. But he accepts no responsibility for what he has done, instead flimsily blaming a third party.

This led him to consider giving up on life until he gained power that he then used violently for the selfish goal of murderous revenge. It is a mission he at times carries out with a dark twisted sense of humour and feels is in it’s own sense heroic.

In direct contrast Peter Parker used his newfound power selfishly too, but for financial gain as opposed to anything truly violent or hurtful. He even resolved to use his financial gains to help a third party, his aunt and Uncle. Like Brock his ego and selfishness led him to make a mistake that allowed a dangerous individual to go free. And like Brock he paid for that act, but the cost was far larger than simply losing his career.

When the dust settled he accepted responsibility for his mistake and blamed himself for what happened and went on to do the same for other events in his life. This included many things that he wasn’t honestly responsible for. He then used his powers to altruistically defend life as much as he could, simply because he felt it was the right thing to do. And he never gave up on his own life no matter how heavy the burden became, often employing witty good natured humour to help him deal with things.

Or to really boil it right down, Spider-Man is a hero who embraces the responsibilities of his life and uses his powers to safeguard life, whereas Venom/Eddie Brock is a monster who doesn’t truly take responsibility for anything and uses his powers to endanger life.

I don’t know if that was truly David Michelinie’s intent in creating Venom. If it was then his interest and focus for the character was evidently elsewhere.

Nevertheless in this sense comic book Eddie Brock is not only a dark reflection of Spider-Man, but a damn good one too.

Creative Value

Eddie Brock in so far as his motivations are concerned amounts to a disturbed individual with an obsessive hatred for Spider-Man over an imagined slight.

From a creative perspective this is actually a pretty great conception for a Spider-Man villain than most people give credit for.

I’m sure many people reading this essay series will simply hand wave a lot of what I’ve outlined in prior instalments as:

He’s crazy so he can do anything. Lame!

However that is grossly oversimplifying what I’m saying.

A vital part of Spider-Man’s conception is that he is (relatively speaking) the everyman superhero who juggles his secret identity with the realistic ups and downs of life. Peter Parker’s secret identity not only serves to allow him to have those common life experiences, but also protect himself and those close to him from danger at the hands of his enemies

Of course these enemies mostly consisted of Spidey’s established rogue’s gallery of super villains. Readers could presume the numerous nameless common crooks Spidey had nabbed might seek vengeance upon him if they knew his secret identity

However Eddie Brock represented another side to Peter’s foes. He was the unseen enemy. One of the dangerous and disturbed individuals who wish to do serious harm to Spider-Man and his loved ones for irrational reasons.

This is not only very much in line with Spider-Man’s core concept as it is entirely realistic, but it is also pretty frightening. Perhaps it is even frightening precisely because it is entirely realistic.

Most of us do not have actual enemies in our lives who want to do us serious harm. But Eddie Brock represents how sometimes in life you can earn the ire of someone dangerous for no logical reason. Maybe something you did had an unpredictable tangential effect that negatively impacted someone. Maybe you just bumped into the wrong person. Or maybe you just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In these ways the existence of Brock as a villain reinforces Spider-Man’s need for a secret identity. He just reinforces that need from a different, uncommonly tapped angle than one might expect.

Original Origin

As I touched upon back in Part 1 David Michelinie’s original origin for Venom was very different from what we wound up with. Let’s revisit what he said in his own words.

Initially she [Venom] was a woman...The whole idea is that whenever I write a character I try to utilize the unique aspects of that character. And one thing Peter Parker had that no one else had was his spider sense...Someone flings at him from behind its a reaction he doesn’t even think about it, he ducks. And this has saved his life so many times I started thinking ‘Well, what if there was a villain who didn’t trigger that spider sense? How would he react? How would he cope with that?’

And they had already established in Secret Wars that the black costume didn’t affect Peter’s spider sense. So I started working out a character who would join with the symbiote costume and actually be a villain...

...My original origin story had been a woman who was pregnant and...her husband was trying to flag a cab as she was going into labour, and a cabbie was driving along looking into the sky at the Living Monolith, tying it into that graphic novel, [Michelinie wrote the Graphic Novel in question] where Spider-Man was fighting the Living Monolith...and he hits the husband and kills the husband...the shock of this sends to woman into premature labour and she loses her child, all because the cab driver was watching Spider-Man. So she became unhinged and when she got out she had this fanatical hatred of Spider-Man, blaming him for the loss of her husband and their unborn child. And that drew the symbiote to her and she became one with the symbiote and was going after Spider-Man...

Michelinie’s plans changed though when he was apparently told readers wouldn’t accept a woman fighting Spider-Man.

Many people use this original story as ammunition against Venom’s origin from ASM #300. Their points generally focus upon how the alleged problems with Venom stems from Michelinie having to come up with something different for his character at the eleventh hour.

However that really doesn’t quite add up when you really think about it.

Surely if Michelinie et al were conceiving their new male Venom at the last minute it’d make sense to just play out the same intended story but simply switch the roles and genders. That is to say that in the revised origin it was Eddie Brock who witnessed his (possibly pregnant) wife run over by a taxi driver who was too distracted by Spider-Man. Consequently he would then blame the wall-crawler for his loss?

But what we got in ASM #300, whilst retaining a few broad concepts from the intended origin (a stranger to Spidey blames him for ruining their life, bonds with the symbiote to kill him, etc.), is essentially a page 1 rewrite of the Venom character.

Brock’s origin and desire from revenge come from a radically different place from his female prototype. In fact they are actually much more complicated.

I do not mean more complex, I mean that the A>B>C chain of events forming his origin has more elements to it and less direct than Michelinie’s original version of Venom.

Compare and contrast

a) During a graphic novel your supposed to remember, a cab driver is distracted by Spider-Man swinging by>runs over pregnant woman’s husband>the shock of seeing this causes pregnant woman to lose baby>woman blames Spider-Man>woman becomes unhinged>woman bonds with symbiote and becomes Venom

To

b) Someone confesses to Eddie Brock that he’s a serial killer from this older Spider-Man story you’re supposed to remember>Brock publishes the story>Spider-Man catches real killer>Brock is fired>Brock is unable to get work other than sleazy tabloids>Brock blames Spider-Man>Brock contemplates suicide but is super religious so he goes to a church>symbiote finds and bonds with him and they become Venom

One is a lot simpler and more direct than the other right?

In other words it is unlikely that Michelinie just threw something together at the eleventh hour.

More than this though, many of the ideas underlying Venom’s motivations are still present in the original female (let’s call her Edwina) conception of the character.

· Both Eddie and Edwina’s origins tie into a previous storyline. The Death of Jean DeWolff and Revenge of the Living Monolith respectively.

· Both endure misfortune that Spider-Man is tangentially involved with but cannot reasonably be blamed for.

· Despite this both latch onto Spider-Man for ruining their lives.

· Both stories involve a third party more directly at fault for their misfortunes. For Edwina it’d be more logical to blame the cab driver and for Brock it’d be more logical to blame Emil Gregg or even Stan Carter.

Note what Michelinie also said in his rundown of Edwina’s backstory (emphasis mine).

So she became unhinged and when she got out she had this fanatical hatred of Spider-Man, blaming him for the loss of her husband and their unborn child. And that drew the symbiote to her and she became one with the symbiote and was going after Spider-Man…

‘Unhinged’ and ‘fanatical hatred’ a descriptors entirely applicable to Eddie Brock as well as Edwina. As I went to great pains to illustrate in prior instalments, Eddie Brock is a man not in his right mind. He is not someone who is operating along sane, rational or logical lines of reasoning, at least not the kinds most people live their lives by. Understanding this is the key to grasping Brock’s intentions as a villain and his motives for despising Spider-Man.

Michelinie’s recounting of Edwina’s backstory also arguably supports another facet of Venom’s origin: the idea of him being an everyday person and a stranger to Spider-Man. Like Brock Edwina was someone Peter Parker didn’t know. She was a civilian affected tangentially by his actions as Spider-Man and who then blamed him for an imagined slight. This touches on both the fear factor of Venom being someone who could exist in reality, the philosophy of Spider-Man as an everyman and arguably the idea of Venom as a stalker character.

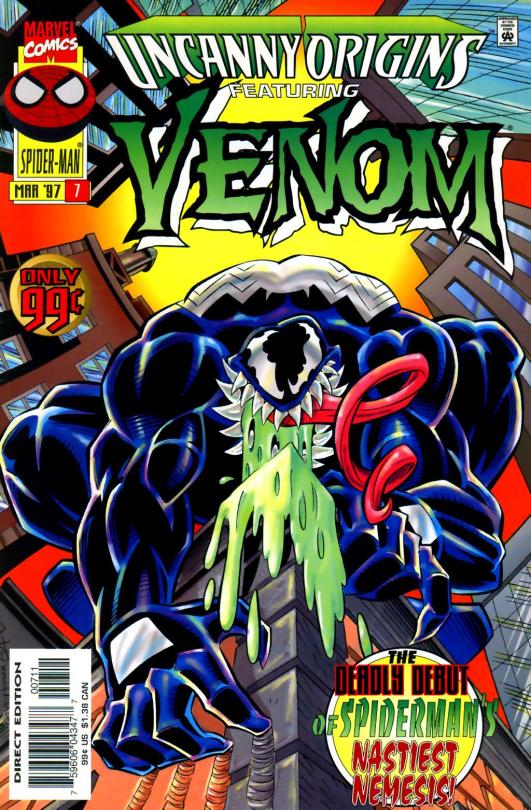

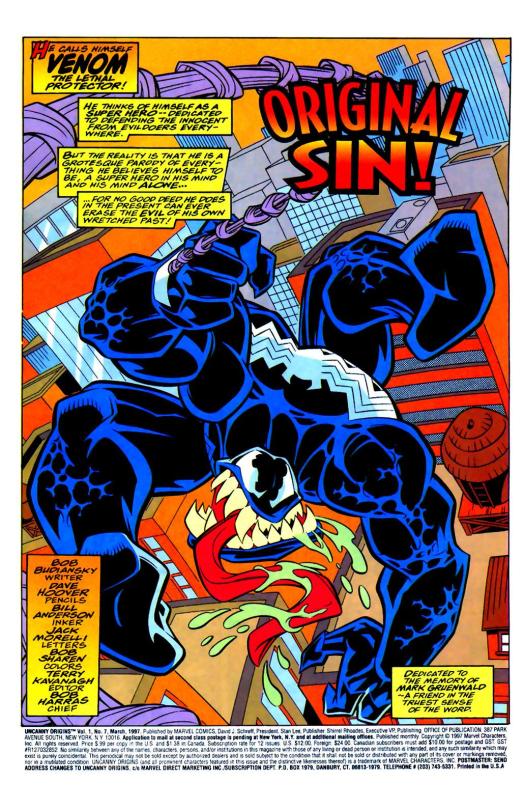

Uncanny Origins #7

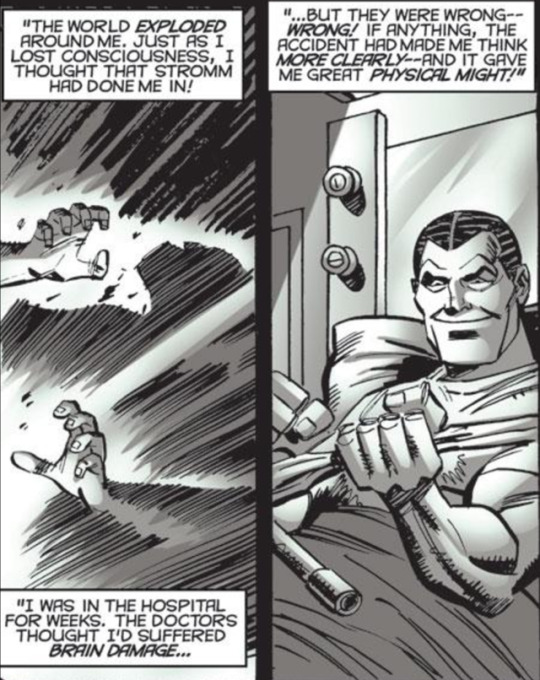

As I mentioned in the main body of the essay series, Uncanny Origins #7 is a retelling of Brock’s origin and other events in his life.

It is however more than likely non-canonical due to the various contradictions to older stories it presents. Nevertheless it does illustrate (perhaps more clearly than Amazing Spider-Man #300) a lot of what I’ve discussed about Brock from Part 7 onwards.

In the retelling you see

Brock’s ambition

His narcissism

His being called out for shoddy journalism (and thus by extension his lying about his skills in ASM #300)

The erosion of his self-esteem

His growing obsessive hatred of Spider-Man

How this was informed by Spider-Man’s costume

The religious context he views his transformation in

And of course Brock’s warped perception of reality and delusions. This is even called out by Venom himself when the story retells his transformation into an anti-hero

Note however that the retelling goes beyond the events of ASM #300

Some Circumstantial Evidence

There is some further food for thought to be considered regarding the ‘unsatisfying mystery’ of Venom’s identity.

First of all, lets bear in mind David Michelinie’s prior work. This is the man who co-created enduring characters such as Scott Lang, Taskmaster, Justin Hammer, James Rhodes and many others. This is the man who scripted/co-plotted what is regarded as the definitive Iron Man run. This is a writer who had at least around ten years worth of experience writing comics by the time he penned ASM #300.

With this in mind I find it extremely difficult to believe that a writer with this much experience would honestly make such a rudimentary misstep as to have a mystery story, then reveal the culprit as someone whom no one could have guessed because he was a complete stranger to the audience.

Even novice writers know enough about mystery stories via pop cultural osmosis to reveal the culprit’s identity as someone the readers already know, or at least could’ve become aware of in the course of the story.

It is therefore very suspect that such a massive and obvious mistake would be undertaken by a writer who’d been around the block a few times by 1988. In the past I’ve criticised the way Dan Slott handles his mysteries but even the flaws in his mystery storytelling never comes from revealing someone to be a complete unknown. His big reveals are genuinely reveals, with the culprit being someone the readers would be familiar with, even if they might not have been able to deduce them as the culprit in the first place

Then you have the fact that Michelinie spoke about the origin of Venom with critically acclaimed writer extraordinaire, Peter David.

Apparently a writer of David’s calibre felt no pressing need to point out the seemingly obvious oversight that Michelinie was resolving a mystery by revealing the culprit as an utter stranger to the audience. Less than a year before ASM #300 David himself had to resolve the controversial Hobgoblin mystery and as unsatisfying as this was to many people, he certainly didn’t just say it was someone no one had ever met.

Furthermore David has been on record as stating he really likes Venom and felt he had a good start as a character. Which is an odd thing for such a skilled and acclaimed writer to say about a mystery character’s identity being completely impossible for anyone to solve.

That is unless as I stated in Part 5, the Venom storyline was never intended as a legitimate mystery story in the first place.

This is also backed up when one considers that Venom’s presence in ASM #300 was apparently because then editor Jim Salicrup wished to debut a new villain.

Regardless, Salicrup seemingly didn’t feel the need to point out that the reveal of Venom’s identity was obviously unsatisfying as a resolution to a mystery storyline. One would imagine that as an editor shrewd enough to have made Kraven’s Last Hunt runt through all the Spider-Man titles and innocuously referenced recent issues in ASM #298, he’d catch such a glaring problem. And in catching it would demand the character’s identity be someone the readers were familiar with.

But he didn’t. Which makes quite a bit of sense if the point was not that he was the centre of a mystery so much as he was simply a new character.

Finally, whilst this doesn’t quite prove my points definitively I did in fact go so far as to personally ask David Michelinie directly about the issue of Venom’s identity.

ME: Mr Michelinie, I am currently writing a series of articles analyzing Venom’s earliest appearances and wondered if you could be so kind as to answer a query I had about Amazing Spider-Man #300.Essentially I would like to know why did you choose to make Venom/Eddie Brock a previously unknown character?

DAVID MICHELINIE: It was a new character, a clean slate, one with a fresh background, origin, personality and motivations. Why would I want to limit what I could do with it by making it a previously known character?

I strongly feel the above further cements that Venom’s status as a new character was the real mission statement behind him, as opposed to being the subject of a mystery story.

Spectacular Misconceptions

In Part 3 I discussed how the readers mistook some of the core ideas behind Venom and saw something different in their place. This then led to them misunderstanding and misinterpreting the character.

However this phenomenon is not exclusive to the comics.

On the (exemplary) Spectacular Spider-Man Animated Series Eddie Brock was a supporting character, with his arc throughout the first season gradually building to his transformation into Venom.One particularly talked about scene for his character was in episode 11, ‘Group Therapy’.

In the episode Eddie Brock takes Mary Jane Watson out on a date to get back at Peter Parker for several perceived slights.Their date consists of a less than safe motorcycle ride wherein Brock rants about Peter in an angry and unhinged manner, including mentioning the death of their parents.

Many viewers of the show felt the scene was out of nowhere and inconsistent with the character as had been established. This point was made particularly in light of earlier episodes such as episode 3 ‘Natural Selection’, in which Brock (a normal young man) risked his own life to try and fight the Lizard.

However the intention by the makers of the show was to convey that Brock was in fact somewhat unhinged and had a death wish. His risking his life against the Lizard wasn’t meant to be taken as an act of heroism but as an example of very dangerous recklessness, feeding back into his unsafe driving later on.All of which was meant to underscore how this show’s version of the character was somewhat in love with death due to the loss of his parents.

For whatever reason the idea and intentions of the character as presented didn’t quite reach many members of the audience and the same is true of the comic book Venom too.

Professional Opinion

The character of Venom is near and dear to me and it is because of that affection that I was inspired to write this essay series and make it as comprehensive as possible.

To that end when it came time to tackling the sticky subject of Brock’s motivations I wanted to be able to speak with a certain degree of authority.

Consequently I actually printed off the relevant pages of Eddie Brock’s earliest appearances from Web of Spider-Man and Amazing Spider-Man #298-300, wrote up some background context presented them to someone who’s studied, taught and worked in the field of psychology, even writing a psychology curriculum. They also have a keen interest in literary analysis but relatively little knowledge of comic books and Spider-Man in general. This is because as a 58-year-old resident of the United Kingdom their potential exposure to the wall-crawler was limited at best.

We then had a few lengthy conversations about Brock’s mental state and motivations and they helped me to pin down many of the points I’ve made in the course of this essay series.

It was this psychologist who outright diagnosed Brock as someone experiencing Delusional Disorder as part of a serious psychosis.

They also corroborated that were we to take Brock and Spider-Man as analogues to real life people that Venom’s origin and motivations were entirely believable, even ignoring the influence of the symbiote.

Conclusion

Venom/Eddie Brock as presented in Amazing Spider-Man #300 is categorically NOT the poorly written or poorly conceived mess of a character that people have painted him as since 1988.

Rather the character’s perception has suffered due to two key intertwined factors.

Unwarranted presumptions of the character then exacerbated by somewhat poor communication of the concepts underpinning him.

However when one truly examines the character it becomes obvious that there is little wrong with him inherent nature or intentions as a character.

Venom as originally conceived is in fact a pretty clever and psychologically layered character who posed a very potent threat for Spider-Man and had a unique place, even iconic, place in Spidey’s already superlative rogue’s gallery as he touched on themes and concepts close to the heart of the character.

Part 11

#Venom#Venom symbiote#symbiote#symbiotes#marvel#marvel comics#David Michelinie#Spider-Man#Peter Parker#Eddie Brock#The Vindication of Venom#Doctor Octopus#Otto Octavius#Green Goblin#Norman Osborn#Peter David#Jim Salicrup#X-Men#Ghostbusters#Tom DeFalco#Ron Frenz#Brian Michael Bendis#Guardians of the Galaxy#Spider-Girl#Spider Woman#MC2#MC2 universe#Mayday Parker#May Parker#Venom: Space Knight

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

[Editor’s note: Nixon biographer John A. Farrell wrote this comparison of the two presidents in February — well before the firing of FBI Director James Comey. It is reposted here with only light edits.]

We’re barely into the Trump administration and we’ve had war on the press, electronic eavesdropping, a sacked attorney general, humongous demonstrations, fury over a Democratic National Committee break-in, Cold War–style skirmishes, and scandalous intrigues akin to Watergate.

Sound familiar?

“Imagine packing 6 yrs of the Nixon admin into 3 weeks,” tweeted Nicole Hemmer, a scholar from the University of Virginia’s Miller Center (and Vox columnist), in February. “It’s like Nixon speed-dating.”

Veteran hands like Dan Rather, Bill Moyers, John Dean, and William Kristol have joined youngsters like Rachel Maddow in drawing parallels between Richard Nixon and Donald Trump.

As the author of a new biography of Nixon, I get asked — a lot — how I plotted the book’s release to coincide with the surge in discussion, in the press and social media, of similarities between the disgraced 37th president of the United States and his latest successor, Donald Trump.

Having lived the past six years with Nixon in my head (I seek no pity; just buy the book), I approach the idea of comparing the two leaders with caution and restraint, for there are important differences.

As bad as Nixon was, for example, he never embraced white nationalists, much less sat one on his National Security Council. Nixon supported every major civil rights bill in the 1960s, and may have lost the 1962 gubernatorial election in California as a result of his spirited denunciation of the John Birch Society, the alt-right wack jobs of their day. “It was time to take on the lunatic fringe,” he wrote to Dwight Eisenhower.

Which is not to cast Tricky Dick as a saint. Fallacious comparisons cut both ways. When Trump dismissed acting Attorney General Sally Yates, a Justice Department holdover from the previous administration, for declining to defend his executive order on immigration, the episode was immediately compared to Nixon’s “Saturday Night Massacre.” But Trump’s move hardly rates with Nixon’s. The stakes were far higher in 1973, with war in the Middle East, a nuclear alert, and the resignation of a corrupt vice president as a backdrop. Nixon’s own attorney general and his successor resigned over principle after refusing to fire the Watergate special prosecutor, before Solicitor General Robert Bork stepped in to do the deed.

So restraint keeps me from overstating the echoes. But then Trump will produce a performance like his rambling, combative February 16 press conference (“Russia is fake news!”) so rich with “narcissism, thin skin and deeply personal grievances,” as NBC’s Brian Williams put it, that the analogies with Nixon’s piteous “last press conference” of 1962, or his Watergate-era clashes with the media, are insistent and appropriate.

And finally, perhaps inevitably, Trump himself joined the game: He alleged that Barack Obama had bugged Trump Tower in an act worthy of “Nixon/Watergate.” (You want to see your book sales leap on Amazon? Have POTUS tweet your topic.)

Why is Nixon the go-to model for presidential misbehavior? For one thing, he is deeply embedded in our lives and culture. The only president to resign in disgrace was famously polarizing long before Watergate. This red-baiter from Southern California was the point man for McCarthyism, earning the eternal enmity of postwar liberals.

In the swinging ’60s, he was the stodgy self-made man: the square in the age of hip. As such, Nixon was a model for Mad Men’s Don Draper and, after stretching out the Vietnam War for four additional years, his reign helped inspire the evil Galactic Empire in Star Wars (according to George Lucas). He may not be the subject of a hip-hop Broadway musical, but he has served as the central figure in an opera (Nixon in China) and played the villain in the X-Men and Watchmen movies.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds / Getty It took Nixon a while to provoke protests like these. On the other hand, some two-thirds of the current American population were either not alive or not residents of the United States, when Nixon resigned in 1974. In my Nixon biography, and in what follows, I’ve tried to portray this oft-caricatured scoundrel, in all his glories, for Gen X-ers and millennials who may know him only as the disembodied head on Futurama.

Thinking through the points of similarity between Nixon and Trump, and where they differ, may help us to better understand both men.

Psychobiography — correlation: modest

The differences in their upbringing — Trump came from a wealthy home in New York, Nixon from the California outback and a family wracked by illness, death, and poverty — make any comparison between the two men on this score somewhat strained. Yet both are known for self-centered, narcissistic personalities — and these, perhaps were sired by the emotional austerity of their childhoods. Trump exhibits insecurity, harbors grandiose fantasies, and shows a tetchiness about criticism. So did Nixon.

The Nixon home was known for its physical and emotional severity. Frank Nixon was a crotchety and abusive dad described, by a nephew, as “a highly acquisitive person and a slave driver” who “worked all his children and he worked his wife.” Nixon’s mother, Hannah, a devout Quaker, gave the future president his sense of idealism: He really did want to bring peace to the world. But she was preoccupied with his four brothers, two of whom died as youths, and the demands of the family store. Dick craved her approval, but she never, as Nixon famously confessed, told him that she loved him.

Historians tread lightly when it comes to psychobiography, but Nixon’s career “vindicates one of that maligned genre’s most trustworthy findings: The recipe for a successfully driven politician should include a doting mother to convince the son he can accomplish anything, and an emotionally distant father to convince the son that no accomplishment can ever be enough,” wrote Rick Perlstein in Nixonland.

Much of that may apply to Trump. As biographers Michael Kranish and Marc Fisher describe him in their book, Trump Revealed, the president’s father, Fred Trump, was also a disciplinarian, a workaholic, and a skinflint. At 13, Donald was culled from his family and exiled to military school as a disciplinary remedy. It may not be unreasonable to suggest that, like Nixon, Trump has spent his life seeking to fill an emotional void.

The press — correlation: high

It is no accident that both Nixon and Trump are famous for waging war beyond reason with the press. In men with their backgrounds, criticism may be interpreted as rejection, ripping the scabs from old psychic wounds and inducing emotional pain and hostility.

It’s also no small irony that each was quite successful at courting the press in their early years. Nixon was a protégé of the Chandler family, which owned the then-right-wing Los Angeles Times and promoted Nixon’s career through the simple tactic of imposing news blackouts on his opponents. Trump was a dealmaking playboy in New York’s tabloid jungle. The experiences left both men spoiled by the media’s fawning, cynical about its professed values, and reckless with the truth.

Mark Wilson / Getty Trump surveys the “enemy of the people.” Trump’s well-documented disregard for veracity was well matched by Nixon’s: He lied repeatedly about Vietnam and Watergate as president. When announcing that he was dispatching troops to invade Cambodia, Nixon solemnly assured the nation that the US had been scrupulous, to that point, in observing that poor country’s neutrality. In fact, he had been bombing Cambodia, secretly, for a year.

Nixon was as brash about his lying as Trump. On one occasion, when he thought the camera had stopped filming, Nixon told an interviewer how he had inserted a crude obscenity into a quote from Lyndon Johnson, because it made for a more colorful story — and portrayed Johnson as a vulgar bumpkin. When his aides could not find the chopsticks he used during his famous trip to China, Nixon told them to use any pair for a museum display, as the public would never know the difference.

Striving to maintain control, Trump rages over leaks. Nixon, too, confessed to being “paranoid” about leakers, and famously declared: “The press is the enemy.” Trump has friends in some corners of the media, and his declaration of war may be cynical and manipulative. For Nixon, the hate was real.

Trump, erupting in nocturnal tweets — emissions quite similar to those captured on Nixon’s White House tapes, except that they are instantaneously blasted out to tens of millions of Twitter fans — has taken it further. The press is not just his enemy, he tweeted, but the “enemy of the American people.”

Their politics — correlation: modest

Trump and Nixon both rode the politics of grievance — particularly white grievance — to the White House.

“I am your voice,” Trump told the disaffected electorate of the South, West, and Midwest, who responded by giving him an Electoral College majority. In his speeches, Trump called for the return of “law and order,” just like Nixon in 1968. “The silent majority is back,” Trump said, identifying his voters precisely as Nixon did. “We are going to take the country back.”

The division between coastal elites and the heartland is a hardy theme in American political history — the tension between frontier farmers and the Founding Fathers led to open rebellions in 1787 and 1791. In crises, the country draws together, then the old divisions reemerge in times of peace.

The gulf yawned after World War I, when the carnage of industrial warfare and the doctrines of scientific and moral relativity inspired a fundamentalist response in the midlands. Americans came together during the Second World War, but the rifts reappeared thereafter. In 1946, a young Navy veteran, running as a Republican, unseated a New Deal Congress member in rural California with a campaign that promised, “Richard Nixon Is One of Us” — not one of the pointy-headed pinko elitists running things in Washington.

Arriving in Washington, as a member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Rep. Nixon embraced journalist Whittaker Chambers, a reformed communist agent, and went to war with the establishment by identifying one of the New Deal’s golden lads, the former diplomat Alger Hiss, as a Soviet spy.

It was “an epitomizing drama,” Chambers wrote in his memoir Witness, a book that would become a bible for the conservative movement. There was “a jagged fissure” between “the plain men and women of the nation and those who affected to act, think and speak for them … from their roosts in the great cities, and certain collegiate eyries.” The left “controlled the narrows of news and opinion,” Chambers wrote, but “my people, humble people, strong in common sense, in common goodness” were led and inspired by Nixon — “the kind and good.”

Nixon used the Hiss case as a launchpad to the Senate, and then to a spot as Eisenhower’s running mate. He survived a brush with scandal over a campaign slush fund filled by wealthy businessmen with a now-legendary televised address, in which he made memorably mawkish mention of his mortgage, his wife’s cloth coat, and the family cocker spaniel, Checkers.

“The sophisticates … sneer,” wrote columnist Robert Ruark, but Nixon’s speech “came closer to humanizing the Republican Party than anything that has happened in my memory. … Tuesday night the nation saw a little man, squirming his way out of a dilemma, and laying bare his most private hopes, fears and liabilities. This time the common man was a Republican.”

That was 1952. Long before the ’60s, the culture war was raging. The ’50s were “the Nixon years,” columnist Murray Kempton would write, when “the American lower middle class in the person of this man moved to engrave into the history of the United States, as the voice of America, its own faltering spirit, its self-pity and its envy, its continual anxiety about what the wrong people might think, its whole peevish resentful whine.” And so Trump and his legions follow Nixon down a well-worn path in American politics.

However, there is one significant difference in how Nixon and Trump got elected. As circumstances had it, in all three of Nixon’s campaigns for the presidency —against John Kennedy’s “New Frontier” in 1960, amid the chaos of 1968, and against George McGovern in 1972 — he ran as the candidate of moderation, of calm and experience. His speeches were generally soothing.

A young Navy officer named Bob Woodward cast his vote for Nixon, convinced he was the candidate who could end the Vietnam War. Even Hunter S. Thompson bought in.

“For years I’ve regarded his very existence as a monument to all the rancid genes and broken chromosomes that corrupt the possibilities of the American Dream; he was a foul caricature of himself, a man with no soul, no inner convictions, with the integrity of a hyena and the style of a poison toad,” Thompson wrote in 1968. But “the ‘new Nixon’ is more relaxed, wiser, more mellow.” Nixon’s were campaigns, as the political scientists Richard Scammon and Ben Wattenberg put it, of “social stolidity.”

Trump is anything but stolid.

Monkey-wrenched elections — correlation: high?

It is a testament to the efficacy of the Republican cover-up that four months after a foreign power affected — may even have determined — the outcome of an American presidential election, we still don’t know the facts. The timidity of the electorate, permitting Congress to let this pivotal question go unanswered, is stunning.

Ira Gay Sealy / Getty Anna Chennault was Nixon’s secret liaison with the South Vietnamese government before the 1968 election. The extent of President Trump’s possible contacts with a foreign government before the 2017 election has come under scrutiny.

From what we do know, it is safe to say that the Russians sought to influence the outcome of the 2016 election, in favor of Donald Trump. We don’t know how or if he and his advisers, in contacts with Russian officials, acted to further the illegal hacking of Democratic organizations and officials. We know that Trump publicly encouraged the Russians to do so (though whether this was a serious request or a glib comment is debatable). This has been written off, like several such misdeeds, as “Trump being Trump.”

In Nixon’s case, it has taken almost half a century for the truth to come out about the 1968 election — about his own conspiring with a foreign power, and the steps that he took to affect that year’s outcome.

Nixon feared that Lyndon Johnson’s election year initiative to negotiate an agreement that would bring an end to the Vietnam War was nothing more than an “October Surprise” designed to elect Vice President Hubert Humphrey. (LBJ had pulled such a trick in the off-year elections of 1966.) And so Nixon employed a campaign official, Anna Chennault, to act as a go-between and persuade South Vietnam to drag its feet and scuttle peace talks with North Vietnam. He — and she — promised the South Vietnamese better terms if Nixon won.

Tragically, peace was indeed close at hand in 1968. The Soviet Union, wanting to promote Humphrey, had promised Johnson a “breakthrough” in the talks and vowed to pressure North Vietnam. But Nixon’s attempts to monkey-wrench the talks were successful. In a telephone call to Sen. Everett Dirksen, a bitter LBJ, who had been getting details of Nixon’s machinations from electronic eavesdropping conducted by US intelligence agencies, accused Nixon of “treason.”

(Trump has offered no evidence for his claim that his campaign was “tapped” by President Barack Obama last fall, but there is no doubt that LBJ was eavesdropping on Chennault, a Nixon campaign official, in her discussions with the South Vietnamese Embassy in Washington.)

There is a law — the Logan Act — that makes it illegal for a private citizen to interfere in the foreign affairs and diplomacy of the United States. Nixon appears to have crossed that line; without more facts, we cannot say that Trump did too.

The deep state — correlation: modest

Like Julius Caesar, cut down by Brutus and a gang of conspirators, Richard Nixon fell victim to a coalition of mutinous forces. He had clashed repeatedly with Congress over its power to declare war, to appropriate funds, and to have access to presidential documents and tapes. He declared war on the press. His antipathy for the State Department, the CIA, the military brass, and other power centers was well-known, and his reliance on backchannel diplomacy with China and the USSR spurred the Joint Chiefs of Staff to plant a spy in the White House. Nixon may also have alienated the federal judiciary by pledging to end its lifelong terms and security.

How low has President Obama gone to tapp my phones during the very sacred election process. This is Nixon/Watergate. Bad (or sick) guy! — Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 4, 2017

The FBI offers an instructive test case on what Nixon’s rash antipathy yielded. Nixon had come to power in Washington with the help of Director J. Edgar Hoover, but after Hoover died, the president provoked the bureau by trying to install a Nixon loyalist as a replacement. “Deep Throat” — the legendary anonymous source for Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward — was Mark Felt, a deputy director that Nixon passed over when choosing Hoover’s successor.

Trump has been tormented by leaks he blames on Obama holdovers in the national security agencies and other entrenched bureaucracies. Trump profited during the campaign from FBI Director James Comey’s eleventh-hour revelation about Hillary Clinton’s emails. But Comey was reportedly outraged by Trump’s allegation that Obama tapped Trump’s headquarters during the campaign and, according to leaks, demanded a public repudiation of the imputation. (And now, of course, Comey has been fired.)

Scandals — correlation: to be determined

There are more than half a million responses to a Google search for Trump and Watergate. But as much as his critics hope to see the 45th president exit the White House like Nixon, we have a long way to go before “Russiagate” is reasonably equated to Watergate.

There are obvious parallels. Both scandals stem from break-ins at the Democratic Party headquarters, whether real or virtual. Both involve electronic eavesdropping. And credit must be given to Roger Stone, a minor figure in the Watergate wars, who managed to survive the decades since and surface once more in the Russiagate stew.

Yet Nixon had years to dig his grave, and the Watergate scandals were, as Woodward and Bernstein famously wrote, “a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage.”

The DNC headquarters at the Watergate were one of a half-dozen targets for burglary and/or bugging, including the campaign headquarters of Sens. Edmund Muskie and George McGovern and the offices of the psychiatrist who treated Daniel Ellsberg, leaker of the Pentagon Papers. By the time Nixon resigned, Watergate was a vast umbrella. The scandal brought to light subsidiary issues — like whether Nixon shortchanged the Treasury on his income taxes, and used taxpayer funds to protect and improve his Florida vacation home — that have obvious correspondence to Trump’s behavior.

But there will have to be some remarkable revelations — proof that Trump and his aides offered inducements to the Russian hackers — before Russiagate can be compared to Watergate. On the other hand, if it is proven that the Trump campaign, in league with a foreign power, stole the White House, it could supplant Watergate as the greatest political scandal of them all.

John A. Farrell is the author of Richard Nixon: The Life, which is being published March 28.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart, often scholarly excursions into the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically written by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

People Who Talk Too Much: Why They Do It and How to Handle Them

Listening skills are great, polite, and all that good stuff. But how do you handle the people who talk too much? Here’s how to deal with them.

I’m a good listener, which is a gift and a curse. The gift is I can laser in on the thing everyone yearns for—attention and to be understood. The curse is that… I might end up listening to your endless monologue. Because there are some people who talk too much.

So even though I am a good listener, I don’t give all my time away to attention-craving vampires who want to suck my soul from my-

-wait… I might be exaggerating there, but there’s not much difference when you’re actually caught in a diatribe about the latest this, that, or whatever the hell it is that seems so important to you and therefore me by default…

…man

*wakes up

The mirror neurons, talking too much, and empathy

Let’s start again. Humans are unlike any other animal in how well we empathize with each other. We gain a strikingly accurate sense of how someone’s feeling, almost as if we were them. This seems to be due to the function of ‘mirror neurons’ in the brain.

The idea is, due to mirror neurons, I simply look at your facial expression and body language and roughly gauge what you likely experience as if I were you. So this allows for very intricate connections between people during an interaction *you’d think people would also be able to tell when they speak too long…*

Note: people with autism are more likely to be unsure of how to interpret what the other person might be feeling just by clocking their responses, though they may feel that person’s energies intensely.

But you could also just be a chatterbox who loves to talk, and talk, and talk… zzzzz.

Okay, but is a chatterbox such a bad thing?

I’m awake again… Often you don’t miss what you had until it’s gone. Chances are if someone likes talking with you, they like and trust you. So, getting paranoid about them and making them into ‘the bad person’ *like that grey donkey from Shrek* might not be such a great thing.

And people who talk too much, well, really, anyone can develop the habit of talking a lot. It feels good to be listened to! [Read: 10 ways to be a better listener]

Say you had a friend who was really chatty. Way more chatty than you naturally are. If you just stopped replying to them or started being rude, they might straight up get offended and stop hanging out with you. Later, you might end up realizing that despite the extreme talking in your ear, you actually really enjoyed being around them.

But sometimes people talk in a way that feels overbearing, as if they try to dominate or control you in some way. This type of relationship isn’t worth it and remove myself from those people or dealing with them leads to a 1000% improvement. The question is how do you deal with that person without it blowing up in your face? [Read: 13 creepy signs your friend is secretly an energy vampire]

The people who talk too much

Well, first we need to dive into the reasons why someone might chat LOAADSSS… you know like the saying says—seek to understand first, then to be understood.

#1 They may be a raving lunatic extrovert. This just is what it is. Introversion and extroversion, in the clinical psychology world, are social science based descriptions of personality. Some people like to talk, man. It amps them up, get them excited about life, and gives them energy.

Meanwhile, for others it becomes tiring if overdone. An extremely chatty person could be on the extreme end of extroversion. [Read: Introverts vs. extroverts: Which side are you on?]

#2 They may be narcissistic. To be honest, everyone likes to talk about themselves but most have enough common sense to limit it. If a person seems to make themselves the subject of every conversation they may just be self-indulgent. [Read: Conversational narcissist – Do you love talking and hate listening?]

#3 They may be very articulate. Being able to think and string accurate words quickly is a skill. It’s also a very powerful tool and potential weapon. When you know you express yourself exceedingly well, the question becomes ‘why not do that a lot and influence circumstances?’ Some people have this skill down pat.

#4 They may be insecure. Stillness, quiet, solitude, meditation, silence, arghhhh!! When you’re not talking or being exposed to stimulus, your thoughts and feelings quickly flood you. We often suppress negative feelings with food, entertainment, and other distractions.

Very talkative people tends to use talking as a way of pushing away their own thoughts and feelings. If the top issue for focus is always out there, then you don’t have to deal with the inside. [Read: How to stop being insecure: 15 steps to transform your life]

#5 They may have underdeveloped listening skills. A lot of people I’ve come across who talk overbearingly don’t like to listen. This isn’t to say that they aren’t astute observers of the world. They may just gain their information through gauging reactions and having verbal combat.

#6 They may be under stress. We live in an unprecedentedly busy world. There is so much noise and stimulus that we don’t always get time to even think and decompress our reality.

To top that, when you’re dealing with a lot of chaos and challenges, it can be a ton of mental data to break down and make sense of. And maybe your way of doing that is to talk it through.

#7 They may be nervous around you. Say you’ve got a crush on someone, admire them highly, or still developing your social skills. In these cases, you’re more likely to make social faux pas.

You feel a need to cover awkward silences with mindless chatter. In many ways, this is a sign of empathy. So, when somebody talks a lot when they you talk to you, take a step back and think about the effect you might have on them. [Read: How to tell if someone likes you – 15 weird and unlikely signs]

#8 They may be jealous of you. It’s like the envious father who bears down on the unusual child: ‘no, this is the way you’re supposed to look at things…’ That kind of assertion of the status quo can be an effort to minimize you as a threat or competition—to not change things. [Read: How to tell if someone is jealous of you]

#9 They may just not like you. Sometimes you just can’t bear to hear someone speak to you because you know you… won’t… like… what… they… say. One way of stopping this is to just speak first and forcefully, so the other person doesn’t get a chance to find their rhythm.

#10 They may want to hold power and control. When you speak, the most it gives you is more opportunity to influence a situation or person. This is especially true when people actively listen to you and respond affirmatively.

#11 They may have no respect for your opinions. If a person doesn’t respect you as a person they probably don’t care about what you’re up to or your personal development. You just become an object they talk at. Perhaps to satisfy their own ego. Or to use as a listening machine while they develop and sharpen their thoughts.

How to deal with people who talk too much

Now that we have why people who talk too much do, let’s look at different approaches to dealing with the overbearing chatterbox.

#1 Being disagreeable. Imagine a random talkative person engaging Obama without giving him the room to speak… If somebody values your thoughts, they want to hear your responses. When I’m repeatedly given no space to speak, I assume that person doesn’t value me enough for me to tolerate their company. Or that they dislike or feel threatened by me.

Depending on the context, I’m more likely to look away, show them I’ve lost interest, or just end the conversation abruptly. People encroach on your personal sense of boundaries bit by bit. It’s better to set boundaries early. [Read: How to say no – Stop pleasing people and feel awesome instead]

#2 Being distractingly non-serious. I don’t engage overbearing talkers in serious conversation. That only makes me invest more of my own energy into their frame. Example:

Them – ‘I wanted to talk to you about this thing.’

You – ‘Did you just call me a thing?’

Them – ‘No, what?’

You – ‘How dare you’ *leaves*?

Distraction technique complete.

#3 Assessing whether they talk a lot with everyone. This gives you an enormous amount of information. Usually they have a reputation for being a force of nature.

People often make jokes about them such as ‘oh wait, I have to prepare myself.’ Then you know it’s not you targeted specifically. Though you may still want to establish fine boundaries.

#4 Interrupting them. Even if someone has a reputation for being a talker, doesn’t mean the person isn’t aware that they’re overbearing. This is the old ‘give them an inch and they’ll take a mile’ principle. If you let them establish a relationship where they’re talking at you, it only grows into a habit. Don’t be afraid to interrupt. [Read: How to set boundaries – 10 crucial steps to feel more in control]

#5 Stopping them by paraphrasing. What happens is that they get into a stream of thought and the energy of what they’re saying makes them feel like they’re making all kinds of clever, rational, and important points.

But then they’re suddenly interrupted with a dissection of their last two sentences and errors reveal themselves… Paraphrasing or interpreting frequently makes the conversation clearer and more involving. [Read: 15 calm and firm ways to be the real alpha]

#6 Frequently asking what the focal point is. If there’s no problem or aim, then they just talk for talking’s sake. Remind them of this by bringing the convo back to a focal point. Then hone in on it ruthlessly, cutting off tangents. You’re not a wall. They need to learn respect for your time.

But on the flipside…

#7 Gaining info. Entrepreneur Gary Vaynerchuk noted how convos between him and Facebook founder Mark Zuckenberg are mostly himself talking and ‘Zuks’ listening.

Gary mused that this could be why Mark’s made so much more money. Listening’s an overrated skill. It teaches you what makes people tick and how to read what people want/will do in the future.

#8 Deciding if you’re compatible. Do you feel better or worse after interacting with this person? If it’s a constant negative, then perhaps find ways to distance yourself from them. There are cooler people to be around. [Read: Stop the craziness in life: How to deal with rude people]

#9 Showing empathy. Sometimes we just want to be understood. Most people don’t spill their life history to anyone who listens. They tend to choose people they like and trust. One of the five ‘love languages’ is ‘words of affirmation.’ If this is that person’s primary love language, then they may be just looking for some empathy. This can be particularly important after a traumatic or stressful experience.

Well I beat this one to death with a barrage of words. Sort of like people who talk too much, just with digital ink…

[Read: 8 signs you’re coming on way too strong]

It can be tricky to work out why someone chats so damn much. But your time and emotional health are important. So seek to understand and establish boundaries with people who talk too much.

The post People Who Talk Too Much: Why They Do It and How to Handle Them is the original content of LovePanky - Your Guide to Better Love and Relationships.

0 notes