#hans ulrich obrist

Text

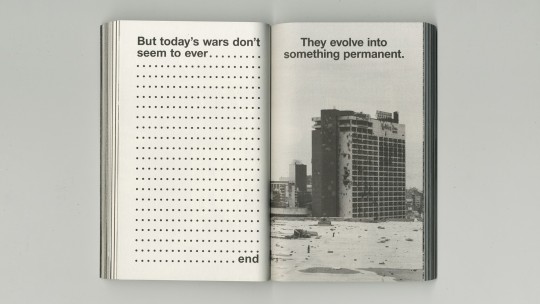

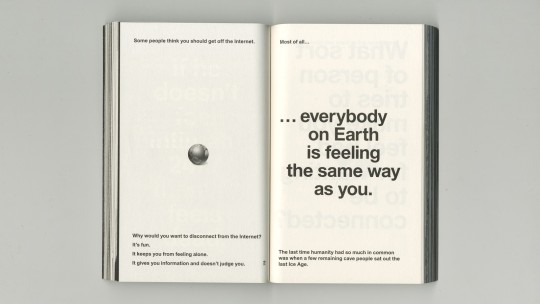

The Age of Earthquakes

Douglas Coupland

210 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enzo Mari, Proposta per un'autoprogettazione, [Corraini Edizioni, Mantova], (1974-)2002 [© Archivio Enzo Mari, Comune di Milano, CASVA. Photo: © Gianluca Di Ioia]. From: Enzo Mari curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Francesca Giacomelli, Triennale, Milano, October 17, 2020 – September 12, 2021

#design#exhibition#enzo mari#gianluca di ioia#hans ulrich obrist#francesca giacomelli#corraini#triennale di milano#1970s#2000s#2020s

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the poet and artist Etel Adnan taught me, "The world needs togetherness, not separation. Love, not suspicion. A common future, not isolation." So a first piece of advice could be to make love, a common future, and togetherness central to the practice.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continents weigh us down. They are thick and sumptuous…

Place is crucial. We are not floating in the air…

The situation of Africa, today, is the great scandal of our time. We all know that and we all know that it is the consequence of colonialism…

In the countryside, there are only dialects, because language distorts very slowly there. But in old cities, languages recreate themselves every day — they appear in the morning and die in the evening…

[I]gnorant cities, self-sufficient cities. In general, they are cities that can bypass the world and the idea of the world, and that's the tragedy of today, because the fact that those cities are perfectly autonomous gives them a tremendous audacity to establish themselves to rise. But they have no continuity with any past…The cities I'm talking about consume their time immediately. Does a city have an obligation to withstand time? Perhaps not…

There's a difference between how we visit sudden cities like New York — in which we are continually shaken from top to bottom, alongside the city itself — and old cities, like Paris or certain African cities — where we can stand alongside the past and the present.

édouard glissant, interviewed by hans ulrich obrist in the archipelago conversations, republished in the european review of books issue 2.

i pulled out my favourite sentences from the glissant interview because i was overwhelmed by how forcefully poetic he was. the style, the language…! it's so—i mean, « thick and sumptuous continents »; « ignorant » cities that « consume their time immediately »…glissant is really so masterful

when i decided to leave london (again…temporarily!) the thing i was most afraid of was losing hold of the commitment to literature that i found there and grew there and protected quite fiercely. so my gift to myself was an annual subscription to the erb, mailed to my new home; it was the first thing i read when i arrived.

there is so much i could say about the essays in it, the design of it, the form; it's really the most beautiful and exciting and innovative print magazine i've read in ages. designed by patrick doan.

but also i really just believe in the erb as a linguistic and literary project. the way they describe it:

The ERB’s gambit is to publish both in English and in a writer’s mother tongue. Pieces written in Greek or Arabic or Italian or Polish or Dutch—or, or, or—will be available in English and in the original…

The ERB is an English-language magazine that resists, or plays with, the seeming hegemony of English. Committed both to a true lingua franca and to exclusive fluencies, to translation and to the untranslatable, we can discover new writers and new solidarities, within and beyond « Europe ».

and i like how they've made this linguistic, cross-cultural commitment quite specific, by publishing in both languages (print is eng only—makes sense tho given printing costs, sadly) and committing to guillemets for quotations instead of the usual “”

i realise it's a bit ridiculous to leave london and give myself the european review of books, but the lrb can get too…posho oxbridge-y (no i don't want another essay on archaeology antiquity classics etc etc i've already overdosed on tumblr #dark academia etcetera)

#prose that attains the status of poetry#european review of books#hans ulrich obrist#édouard glissant

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Oh! Junk. Des choses qui n’ont rien à dire. Mais je m’y accroche, parce que de temps en temps… voilà ! On les voit, elles deviennent visibles, elles parlent, je les vois. […] En fonction de la lumière et des ombres dans la pièce, elles peuvent émerger et devenir visibles.» (Conversation entre Marisa Merz et Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2009)

https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/marisa-merz-hans-ulrich-obrist-2009

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

l'Ultimo Mobile, by Martin Gamper

When Hans Ulrich Obrist heard Enzo Mari and his wife Lea Vergine both died of COVID two days after his retrospective of Mari's work opened at the Milan Triennale, he asked Martino Gamper to come up with a tribute, and then discuss it on the Triennale's Instagram Live, which had been turned into a Mari memorial channel. Gamper made Autoprogettazione-style coffins.

#l'ultimo mobile#the final furniture#enzo mari#autoprogettazione#martino gamper#hans ulrich obrist#quick make some instagram coffins but actually make them tabletop size and we'll just photograph them to look full-scale#rip

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

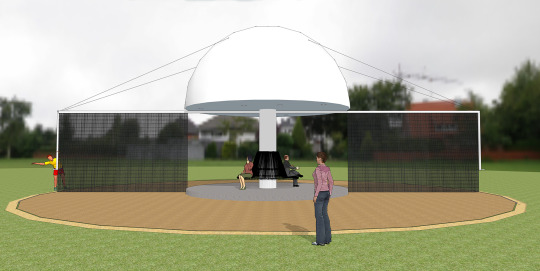

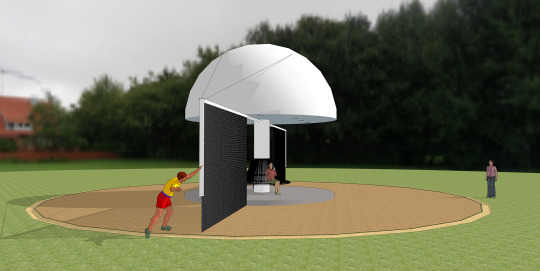

Temp\0

Schöppingen

2013

Matthijs Muller

Temp\0 Temp\0 (pronounced: Temp-io) is a pavilion that offers protection against sun and rain. The only way to reach the pavilion is by crossing a circle of sand and inevitably leave your traces in the sand. Visitors are invited to erase their traces by rotating the eraser-arms, which are attached to the pavilion, with chains hanging down from these arms. They will make the sand look fresh and new again. This way everyone can have the feeling to be the first one to enter Temp\0.

#Matthijs Muller#6v#6varchives#6vtheblog#contemporary art#abstract#modern art#new contemporary#abstract art#agencyofunrealizedprojects#aoup#Hans Ulrich Obrist#modern design

1 note

·

View note

Text

PODCAST 53. UNA SOCIEDAD SIN MEMORIA, Umberto Eco

Hola, compartimos con todos y todas vosotras el nuevo Podcast que ha grabado nuestro colaborador Jocke.

En esta ocasión, su Literatura Oral se centra en una entrevista realizada a Umberto Eco, en 2015, por Hans Ulrich Obrist, titulada “Una sociedad sin memoria”, publicada en La Jornada Semanal.

Os dejamos el…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

James Ernest Geraldo, THU-11

for Module 2: The Languages of Art | IG Post

"3, 2, 1, go.

Okay, okay. Let’s start.

'Practice stillness as a matter of urgency'?

Huh? That doesn’t make any sense. Stillness but in urgency?

Calmness? Inner peace? Daoism? Yin and Yang?

Should I take it philosophically? Or literally?

What the hell am I supposed to do?

Wait.

Let’s close our eyes.

I’m running out of time.

Hmm, what should I do?

Maybe I could just be still and do nothing.

How about just staring outside the window?

Or try stacking irregular objects on top of things?

Or or maybe like sleeping? Probably with aromatic candles?

Hmm, how about meditating? There’s so many of them, what should I do?

I’m running out of time.

I’m too lazy to do any of them, let’s just draw some lines, eyes closed.

1.

2, 3.

4, 5, 6.

7, 8, 9, 10…

12… 14… 15

56… 68… 103…

. . 305. . .

. . . . . .

An output from Evan Ifekoya’s “Do It”, “Practice stillness as a matter of urgency”

----------

As the main description of Do It instructions, they are instructions that are open to interpretations and anyone could do it. As for my output, it could create different outcomes, from the interpretation of the output to even the outcome if they followed my process or interpretation of the instruction. For instance, my friends gave different views upon seeing the output.

0 notes

Text

vimeo

Ian Cheng and Beeple

In this conversation, Ian Cheng and Beeple exchange perspectives on the metaverse, gaming, and other directions for the future of art. They also share some appreciation for each other’s work. Cheng is fascinated by Beeple’s appropriation of figures from politics and pop culture, which he sees as a continuation of modding, fan fiction, and other practices in the robust landscape of grassroots creativity that the internet has enabled. Because of his interest in making dynamic art—such as his sculpture Human One (2022), a column of screens displaying visuals that can be reprogrammed and changed—Beeple is intrigued by Cheng’s Outland commission 3FACE, a PFP that can represent changes in the holder’s personality over time. Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist moderates the conversation, offering insights of his own into the current state of art and culture.

#ian cheng#beeple#outland.art#Hans Ulrich Obrist#art#nfts#simulation#creating#interview#discussion#Vimeo

0 notes

Text

#the age of earthquakes#a guide to the extreme present#Hans Ulrich Obrist#douglas coupland#shumon basar

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

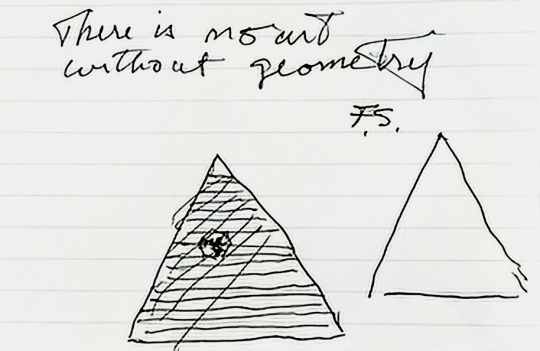

«There is no art without geometry» – Frank Stella (1936-2024)

[...]

Frank Stella

«Monir took geometry off the surface of architecture, and made it into essentially its own surface. She hasn't put it back on the wall; it’s come back as art. She's taking a geometry that is so tied to architecture, actually tied to a wall, and making it an independent surface.»

Hans Ulrich Obrist

«That's such an important point. I read this wonderful interview with Monir by Lauren O'Neill-Butler in Artforum in which Monir said that her work is at all times about geometry.»

Frank Stella

«Ultimately, everyone says, there is no art without geometry.»

Hans Ulrich Obrist

«Who said that?»

Frank Stella

«I just did. [laughs] No, I didn't, I got it from somebody else. I don't know where I got it.»

[...]

Excerpt from: There Is No Art without Geometry: Frank Stella and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian / Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Frank Stella and Suzanne Cotter in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Mousse Magazine, October 1, 2015 (pdf here)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

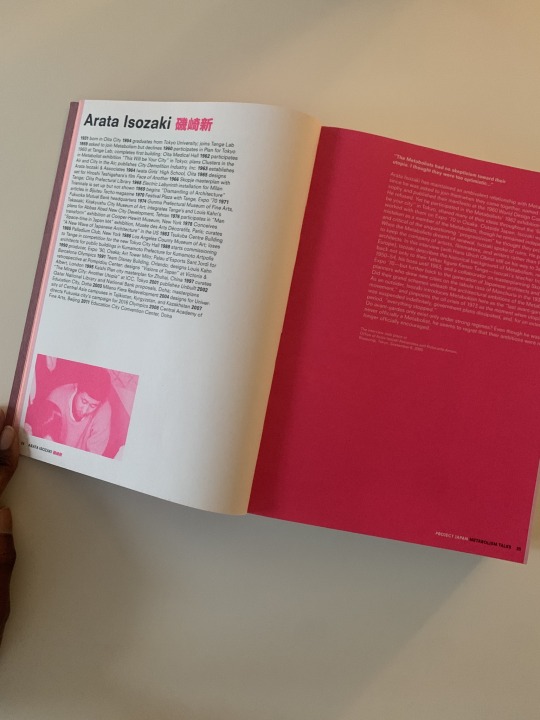

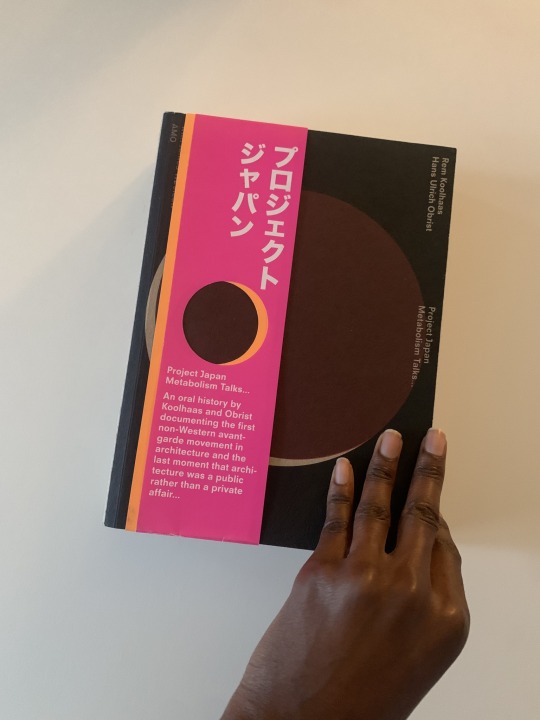

This beautiful book… Project Japan.

#incredible subject and design and thoughts#rem koolhaas#hans ulrich obrist#architecture#the design of this really sets a standard for me. this is the sort of thing I want to make

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 5, 2018

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: You were on the first-ever cover of Interview magazine. How did that come about?

AGNÈS VARDA: Like everybody, I wanted to meet Andy Warhol. I was impressed by his work and how daring he was. I think he changed the cinema completely, simply by opening his camera and letting it go. He dealt differently with time and duration, and he didn’t care about how people would perceive it. It changed the cinema for me. It doesn’t mean that I loved to watch his films—because eight hours is boring—but the concept was revolutionary.

OBRIST: When did you first meet Warhol?

VARDA: We met here and there in New York, at some underground film screenings. In 1967, he invited Jacques and me to visit him at his Factory. A lot of people were there—Nico, the young men acting in his films, beautiful women like his muse Viva. When I was preparing Lions Love (…and Lies), I had in mind to cast Viva, so I went to the Factory to ask Andy to convince her. Andy was nice to me and said to Viva, “This is Agnès. You should work with her. She made a film called Cléo from 5 to 7. It’s a beautiful film.” I loved that. Then he added, “If I had made this film, we would have shot from five to seven.” Andy cared about Viva, and that’s why they decided to make the cover. That cover image is interesting, because the way the three characters are positioned is a total copy of a Picasso drawing.

OBRIST: Was Picasso an inspiration for you?

VARDA: I’m not sure I would call him an inspiration, but I was fascinated by his capacity for invention. The way he changed all the time gave me lots of strength.

OBRIST: In your original Interview story about the making of Lions Love (…and Lies), you talk about Hollywood as a space of freedom. What did you mean by that?

VARDA: The way I worked there was total freedom, given to me by Max Raab, who produced the film. Carlos Clarens, who helped me write the screenplay, said that Hollywood, at its birth, was “an orange grove with breakfast served by the Ritz.” My film is about three characters who want to be Hollywood stars, but they don’t want to play the game. They want to remain naked all the time, have a good time, and say what they want to say. That time was all about sex and politics. The film was happening in June 1968, and the three of them are in bed when they find out about the [Robert] Kennedy assassination. In the screenplay, the day after, Viva learns of the shooting of Andy Warhol, which also happened that week. The TV stations didn’t mention the shooting of Andy Warhol, but the death of Kennedy was commented on nonstop. In the days following Kennedy’s assassination, they took his corpse on a train from Los Angeles to New York to go to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. His corpse’s trip was on TV for days. I remember seeing a woman ironing her laundry while watching the train with Kennedy’s dead body pass by her window. I wanted that to be a part of the film. Three stars plus a TV set.

OBRIST: Where did the title Lions Love (…and Lies) come from?

VARDA: Lions, because of the actors’ hair. Love, because it is a love threesome. And lies, because it’s about the news and Hollywood. On our set, everything was half-fake: Real flowers, fake flowers. Real columns, fake columns. Secrets and lies. And that’s because Hollywood is fake—but true at the same time.

OBRIST: You and Jacques first moved to Hollywood in the late ’60s. What are your memories of that arrival?

VARDA: I remember telling Jacques, “I’ll go with you to America, but if I don’t like it, I’m coming back.” I wasn’t attracted to American cinema, but I fell in love with Los Angeles the minute I arrived. We rented a little house and two white convertibles. In those days, when Jacques was starting to work with Columbia [Pictures] on Model Shop, I loved driving slowly down these endless boulevards. I got very excited not only by the Los Angeles landscape but by that generation. It was a lot of peace and love, hippies, huge Sunday meetings in the parks. The Doors, Buffalo Springfield, and the Mamas & the Papas would come over and play for free.

OBRIST: Were you not in Paris during the protests of May 1968?

VARDA: No, I was in America with the Black Panthers

OBRIST: How did that film, Black Panthers, come about?

VARDA: I was friendly at the time with [the film producer] Tom Luddy, who told me about the marchers in Oakland and about Huey P. Newton, one of the leaders of the Black Panthers, who was in jail. I would take a plane there every Sunday, and I filmed all of them—Eldridge Cleaver, Bobby Seale. I was sometimes alone with my camera, sometimes helped. I would smile and say, “French television,” and they would just let me film. I felt it was important to capture that time when they were fully empowered. A couple years later their movement was all in pieces.

OBRIST: How did it feel to be in California for that moment in time, and then to return almost 50 years later to receive an honorary Oscar?

VARDA: It was the surprise of my life. Those honorary Oscars are given to filmmakers and artists who they respect and admire, but who were never mainstream. I was delighted, of course. The room was filled with all these stars, and here I was with my family. In my head I was dancing, and then it really happened. Angelina Jolie gave me the statue, took me by the arm, and we improvised a little dance.

OBRIST: You’re busier now more than ever. What is the secret that has allowed you to stay creatively active for nearly seven decades?

VARDA: I’m curious. Period. I find everything interesting. Real life. Fake life. Objects. Flowers. Cats. But mostly people. If you keep your eyes open and your mind open, everything can be interesting. The secret is that there is no secret.

OBRIST: How have you allowed yourself to follow these curiosities?

VARDA: What I notice or discover has to grow in my mind. I always wait until the ideas and impulses are so strong that they invade my mind and I have to pursue them. My mind is often half-sleeping, like in a daydream. Then some images come together, some ideas, and then suddenly I have to do it. Like with Cléo from 5 to 7—at the time, there was this collective fear of cancer. People spoke about cancer a lot. The subject of a woman expecting the results of a cancer test felt interesting, and so I decided to do it in real time, with real geography.

OBRIST: How did you feel about being called “The Grandmother of the French New Wave,” when you were just 30 years old?

VARDA: That was related to my first film, La Pointe Courte, which I made in 1954, five years before the blooming of [Jean-Luc] Godard and [François] Truffaut. I used to be the Grandmother of the New Wave, but now I am the Dinosaur of the New Wave. Only Godard and I are left alive.

OBRIST: The Nouvelle Vague was dominated by men. Is that what prompted you to make a film like One Sings, the Other Doesn’t?

VARDA: No, there was no connection between the New Wave and my feminist musical film from 1976. Since 1973, I had written a few screenplays on feminist subjects, but nobody wanted them. So in 1976, I produced One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, about 15 years of struggle as experienced by two women. You know, women used to be put in prison when they had abortions. The last woman to be executed by guillotine in France had been an abortionist. It’s a terrible story, isn’t it? There was a famous manifesto signed by 343 women who proclaimed, “We’ve Aborted.”

OBRIST: Did you sign it?

VARDA: Yes. So did Françoise Sagan, Catherine Deneuve, Delphine Seyrig, Colette Audry, and many more. There were trials. Young women were being put in prison. The manifesto said that this was clearly an injustice. The law was striking down on us. Charlie Hebdo and Minute were calling it the Manifeste des 343 Salopes [“Manifesto of the 343 Bitches”]. There was such contempt toward women’s desire to be free.

OBRIST: Your work has spanned the worlds of film and contemporary art. You and I first came into dialogue during a project for the 2003 Venice Biennale called Utopia Stations, in which Molly Nesbit, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and I asked 120 artists and groups to create small, autonomous structures. We called you hoping that we could somehow convince you to be a part of it.

VARDA: That was one of those calls where you’re ready before the phone even rings. I had already been filming and photographing the heart-shaped potatoes that would appear in that project, “Patatutopia.” And then here arrives this strange news that Hans Ulrich Obrist wants me to join all of these very famous artists in this exciting exhibition.

OBRIST: That was your first installation.

VARDA: The first of many. I started to build actual shacks from composite prints of my own films.

OBRIST: Lions Love (…and Lies) became the basis for one of your shack installations at LACMA in 2013.

VARDA: To tell you the truth, my first real exhibition was in this very courtyard in 1954. I had no idea I could sell pictures. I thought I could just invite my neighbors, and they all came. This courtyard has always been a base for me. I wrote my first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1954 on a table like this one. I just celebrated my 90th birthday, and I often think, “My God, look at all of these waves of work!” It’s not just about memories, because thankfully I’ve forgotten many things.

OBRIST: How did you celebrate your 90th birthday?

VARDA: I swam in the ocean.

1 note

·

View note

Text

vimeo

Agnès Varda: In Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist

Agnès Varda is one of the pioneers of French New Wave Cinema. With a career spanning photography, cinema and visual art, Varda’s works are characterised by a playful yet radical approach to image-making, and the filmmaker’s keen attention to - and appreciation of - the world around her.

#Agnès Varda#Agnès Varda is one of the pioneers of French New Wave Cinema#Agnès Varda: In Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist#FACT Liverpool#Vimeo

1 note

·

View note

Text

Autoprogettazione, Autodistruzione

I know he thinks it's some kind of utopian treat, but Enzo Mari having his collection-filled studio destroyed and his archives sealed for 40 years after his death feels like a personal attack.

Anyway, a bunch of people who could do something about it, including Mari's assistant and Hans Ulrich Obrist, were in a roundtable discussion about Mari and his impact on their lives, organized by disegno journal.

#enzo mari#hans ulrich obrist#kafka asked for his archive to be destroyed after his death and was it? NO IT WAS NOT.#why do you even think the world and/or milan will be in a position to open the communist's archive in 2060? just sayin'

0 notes