#gyrinophilus

Text

Northern Spring Salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus), family Plethodontidae, MD, USA

photographs by Brady O'Brien

#spring salamander#salamander#gyrinophilus#plethodontidae#amphibian#herpetology#animals#nature#north america

413 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Tennessee cave salamander (Gyrinophilus palleucus) in USA

by Chad Harrison

#Tennessee cave salamander#salamanders#amphibians#Gyrinophilus palleucus#Gyrinophilus#Plethodontidae#urodela#amphibia#chordata#wildlife: usa

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spring salamander (Gyrinophilus sp.)

By: Charles E. Mohr

From: Natural History Magazine

1937

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tennessee Cave Salamander (Gyrinophilus palleucus), Appalachian Mountains, Eastern U.S.

photograph by Saunders Drukker | inaturalist CC

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We hung out with these little dudes (gyrinophilus porphyriticus) yesterday and it was wild. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cgpx0ijJZJw/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

Record-breaking salamander -- LiveScience.Tech

Scientists at UT have actually found the biggest person of any cavern salamander in The United States And Canada, a 9.3-inch specimen of Berry Cavernsalamander The finding was released in Below Ground Biology

” The record represents the biggest person within the genus Gyrinophilus, the biggest body size of any cave-obligate salamander and the biggest salamander within the Plethodontidae household in the United States,” stated Nicholas Gladstone, a college student in UT’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, who made the discovery.

The discover is making researchers reconsider development limitations of these animals in severe environments and how congenial underground environments truly are.

Salamanders can be discovered in a range of environments throughout Tennessee. Some types have actually adjusted to reside in cavern environments, which are considered severe and unwelcoming communities due to the lack of light and restricted resources.

Salamanders are among just 2 vertebrate animal groups to have actually effectively colonized caverns. The other is fish, stated Gladstone.

The record-breaking specimen had some damage to the tail, leading scientists to think that it was as soon as almost 10 inches long.

The Berry Cavern Salamander can be discovered in just 10 websites in eastern Tennessee, and in 2003 it was put on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service’s Prospect Types List for federal defense.

“This research will hopefully motivate additional conservation efforts for this rare and vulnerable species,” stated Gladstone.

Story Source:

Products supplied by University of Tennessee at Knoxville Note: Material might be modified for design and length.

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2019/01/26/record-breaking-salamander-livescience-tech/

0 notes

Photo

Tennessee cave salamander (Gyrinophilus palleucus)

Photo by Alfred Crabtree

#tennessee cave salamander#gyrinophilus palleucus#gyrinophilus#hemidactyliinae#plethodontidae#salamandroidea#urodela#caudata#batrachia#amphibia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

spring break 2k19

#mah ert#gouache#illustration#salamander#anthro#amphibian#gyrinophilus#spring salamander#she is a bubble tea Fiend!!!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to catch 311 amphibians in 10 days

Step 1: Deploy pitfall traps across Powdermill Nature Reserve

Step 2: Get out of the way and let nature do the rest

Over the course of 10 days in June of this year, I captured 311 amphibians of 12 different species. Every day, rain or shine, I spent over four hours checking 132 pitfall traps and several more hours identifying, measuring, and weighing the day’s amphibian haul. I did a rinse and repeat of this cycle for 10 days straight. Why would anyone do all of this for what Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, once described as “vile animals” with “a foul odor” (Wahlgren, 2011)? Although this sentiment might still ring true for some people today, I did this because amphibians are in serious trouble—more than 30% of species are facing extinction. The threats to amphibians range from habitat losses to disease epidemics, but these are merely symptoms of the underlying cause: unnatural changes brought about by the Anthropocene. Human-induced alterations to nature are irrevocably modifying biodiversity so rapidly that species we learned about in grade school are now extinct and, if we view amphibians as sentinel organisms, then the worst is yet to come.

The Powdermill Nature Reserve is a protected site in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains where, since 1956—the year it was established by a forward-thinking herpetologist— the property has functioned in a similar way as forests did before human settlement swept across the region. In the early 1980s, scientists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History studied the amphibian community at the Powdermill Nature Reserve and, serendipitously, established the empirical baseline necessary to study how environmental changes have affected amphibian biodiversity in the Alleghenies (Meshaka, 2009).

Examining the results of amphibian trapping during two long ago Junes offers insight into the reserve’s value. In June 1982, 78 traps captured 262 amphibians of 11 species. In June 1983, 54 traps captured 174 amphibians of 11 species. While the species richness has not changed much since the 1980s, there has been species turnover and shifts in abundance, with some species becoming more common in the community. The Two-lined Salamander (Eurycea bislineata), for example, went from 0 captures in June of 1982 and 1983 to 7 captures this June. In terms of standardized trap nights in June (i.e., the number of traps multiplied the number of days opened), a combined rate of 0.11 amphibians per trap was detected across the two years in the 1980s, compared to a rate of 0.24 amphibians per trap this year. What could the ecological scenario be that has led to such an apparent increase in the amphibian capture rate over this 40-year period? Could trophic cascades be involved? Perhaps the protection of habitats in 1956 helped forest regeneration, and this change led to improved stream health and greater water retention later into the season via increased canopy cover. By providing better habitat and more resources for the streamside invertebrates that makeup the main prey base of forest-dwelling amphibians, such a transformed system might benefit amphibian communities indirectly. It’s also possible that some entirely different mechanism produced this result.

The species that dominated captures historically and today was the Allegheny Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus ochrophaeus), which went from 0.048 individuals per trap in June from the 1980s to a slightly increased rate this June of 0.052 individuals per trap. Interestingly, the average body size of female Allegheny Dusky Salamanders has not changed over the 40-year study period, suggesting stability in morphology despite other studies reporting salamander species either shrinking (Caruso et al., 2014) or growing (McCarthy et al., 2017) in response to warmer temperatures brought about by recent climate change. Without the founding of the Powdermill Nature Reserve and the herculean efforts of historical and modern scientists from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, we would not be able to understand the extent that humans have impacted biodiversity, let alone the data needed to solve mysteries of the modern world.

So, when I look at a Spring Salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) or a Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosis) or a Four-toed Salamander (Hemidactylus scutatum) from the Powdermill Nature Reserve, I don’t see Linnaeus’s “terrible animal” with a “ghastly color”, rather, I see profound resiliency in the face of tremendous pressure, and the power that natural history collections and protected areas hold for improving our relationship with biodiversity.

Daniel F. Hughes is the Rea Post-doctoral Fellow in the Herpetology Section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

References:

Caruso, N.M., Sears, M.W., Adams, D.C. and Lips, K.R., 2014. Widespread rapid reductions in body size of adult salamanders in response to climate change. Global Change Biology, 20: 1751–1759.

Meshaka, Jr., W.E., 2009. The terrestrial ecology of an Allegheny amphibian community: Implications for land management. The Maryland Naturalist, 50: 30–56.

McCarthy, T., Masson, P., Thieme, A., Leimgruber, P. and Gratwicke, B., 2017. The relationship between climate and adult body size in redback salamanders (Plethodon cinereus). Geo: Geography and Environment, 4: e00031.

Wahlgren, R., 2011. Carl Linnaeus and the Amphibia. Bibliotheca Herpetologica, 9: 5–37.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Powdermill Nature Reserve#Salamanders#Amphibians#Herpetology#Pitfall Traps#Anthropocene#Biodiversity

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

-- Largest body size of any cave-obligate salamander

-- Largest salamander within the Plethodontidae family in the United States

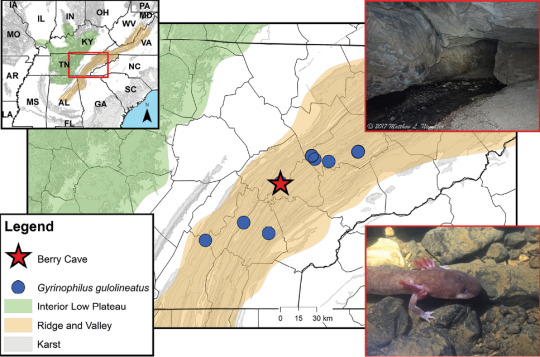

The Berry Cave Salamander, Gyrinophilus gulolineatus. The salamander species lives only in caves, and is endemic to the western slopes of Southern Appalachia (found only within the political borders of Tennessee), where it is known to live at only 10 locations. This individual has a body length of 145 mm (9.3 inches). (An example of a “Plethodontid” salamander: the red-backed salamanders.)

Distribution map for the species:

Excerpt:

During an ongoing study on the demography and life history of the paedomorphic, cave-obligate Berry Cave Salamander (Gyrinophilus gulolineatus, Brandon 1965), we discovered an exceptionally large individual from the type locality, Berry Cave, Roane County, Tennessee, USA. This salamander measured 145 mm in body length and represents not only the largest G. gulolineatus and Gyrinophilus ever reported, but also the largest plethodontid salamander in the United States.

Gyrinophilus gulolineatus is known from just ten localities in the Clinch and Tennessee River watersheds in the Appalachians karst region of eastern Tennessee [...]. The main entrance [to Berry Cave] is in a large sink, with the passage from the entrance steeply sloping down to the main stream passage. [...] The salamander was observed [...] in the margin of a shallow (<0.5 m deep) pool located in a small passage upstream from the main entrance chamber. When first encountered, all but the salamander’s head was out of the water, as it appeared to be moving partially over land to continue upstream. [...]

Salamanders are one of only two vertebrate groups to have successfully colonized and obligately live in subterranean habitats. [The other are fish.] Fourteen species from two families (Plethodontidae and Proteidae) occur exclusively in caves, and most have evolved paedomorphosis [...].

Text, map, announcement as reported here:

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Spring Salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus), family Plethodontidae, Western MD, USA

photograph by Brady O'brien

#spring salamander#salamander#gyrinophilus#plethodontidae#amphibian#herpetology#animals#nature#north america

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

the other day I had a look at this cold forest spring in upstate NY

where within a very short time I was able to locate the holy trifecta of stream salamanders

——

Two- lined salamander (Eurycea bislineata):

the smallest and most common, this lad can be found almost anywhere with cool, flowing water. This individual is kind of dull, but they’re immediately recognizable by their yellowish coloration and yellow belly.

My favorite thing about these guys is their eggs, which have strikingly white embryos.

(not my photo)

Frog eggs are typically black to absorb heat and speed their growth, but most salamanders require cold temperatures- hence why cold springs are some of their favorite habitats. Twolines breed in summer, so they have white eggs to reflect heat.

-

Allegheny mountain dusky salamander (Desmognathus ochrophaeus):

There’s actually two nearly identical species in the region. Based on the shape of its tail, this one appears to be the rarer of the two, ochrophaeus.

Duskies are fast, powerfully built and hard to catch. They can jump with their muscular hind legs and are quick to burrow into mud and gravel. This one is a small, probably young individual- they can grow over 5”.

-

annnnd finally, the one I’d never seen before, the northern spring salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus):

First, notice that it already dwarfs the other two salamanders. Indeed, it’s the biggest plethodontid (lungless) salamander I’ve ever seen. Now have a look at those gills- this thing’s just a baby at 4”. Adults can reach 9” and have a particularly strong habit of eating smaller salamanders.

(not my photo- it’s eating a dusky salamander)

The genus name, Gyrinophilus, means “tadpole lover”, referring to the 3-4 years they spend as larvae before losing their gills. It’s probably because the adults also spend most of their time in the water, so no need for a hasty metamorphosis.

Spring salamanders are usually only found around the cold, pristine water of springs, and are rather rare as a result. All three of these salamander species belong to the family Plethodontidae, all of which lack lungs and breathe entirely through their skin and cannot live outside of very moist, oxygen- rich habitats. Some species are adaptable, but they are believed to have originally evolved in the well- oxygenated mountain streams of the Appalachians in the late Cretaceous. The mountains of the southeastern US is still where the overwhelming majority of the 380 species of plethodontids are found. Most of these species have limited ranges and very specific habitat requirements. They’re threatened by pollution, climate change (salamanders need it cold!) and the potential introduction of the deadly fungal disease Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, similar to the fungus which decimated frogs in the western US and neotropics.

If you live somewhere that has clean flowing streams and a variety of cool salamander species, I recommend going to see them before you can’t anymore.

319 notes

·

View notes

Link

Researchers at UT have discovered the largest individual of any cave salamander in North America, a 9.3-inch specimen of Berry Cave salamander. The finding was published in Subterranean Biology.

"The record represents the largest individual within the genus Gyrinophilus, the largest body size of any cave-obligate salamander and the largest salamander within the Plethodontidae family in the United States," said Nicholas Gladstone, a graduate student in UT's Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, who made the discovery.

The find is making scientists reexamine growth limits of these animals in harsh environments and how hospitable underground environments really are.

Salamanders can be found in a variety of habitats across Tennessee. Some species have adapted to live in cave environments, which are thought of as extreme and inhospitable ecosystems due to the absence of light and limited resources.

Salamanders are one of only two vertebrate animal groups to have successfully colonized caves. The other is fish, said Gladstone.

The record-breaking specimen had some damage to the tail, leading researchers to believe that it was once nearly 10 inches long.

The Berry Cave Salamander can be found in only 10 sites in eastern Tennessee, and in 2003 it was placed on the US Fish and Wildlife Service's Candidate Species List for federal protection.

"This research will hopefully motivate additional conservation efforts for this rare and vulnerable species," said Gladstone.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Researchers capture largest cave salamander in North America

Nicholas Gladstone had to crawl through a watery passage in a Tennessee cave to find the species he was looking for, but as it turned out, it found him first.

“I am usually recruited as the smaller person who can fit into the small cracks,” said Gladstone, a master’s student at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. He climbed upstream through a small, wet area within the expansive cave system and awkwardly moved his head to maneuver through the tiny crevice.

“I turn around and there is this big behemoth before me,” he said. “I freaked out.”

Gladstone was helping capture and mark Berry Cave salamanders (Gyrinophilus gulolineatus), a species specifically adapted to live in caves that occupies only about 10 sites throughout eastern Tennessee, when the largest individual anyone had ever caught and recorded in North America appeared in front of him...

Read more: The Wilderness Society

photo by Dr. Matthew L. Niemiller/The University of Alabama in Huntsville

#north america#caves#freshwater#aquatic#salamander#plethodontidae#amphibian#animals#nature#herpetology#science

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ontario Species at Risk for February 19, 2019 is the Spring Salamander (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus)

Status: Extirpated

What it looks like

The Spring Salamander is the largest member of the lungless salamander family in Canada, growing up to about 20 centimetres long. Lungless salamanders “breathe” through their skin, especially the lining of the mouth.

Spring Salamanders are pinkish or yellowish brown with irregular darker markings and a stripe from below each eye to the nostrils.

Where it lives

Spring Salamanders live in springs, seepages and mountain streams. They must keep their skin moist for respiration and seldom leave the water, although adults will use terrestrial areas within two metres of the stream edge. Females lay their eggs underground beneath the streams and seeps. This species overwinters in the stream bottom or refuges under the banks to avoid freezing.

Where it’s been found in Ontario

In Ontario, there are only two historical records of the Spring Salamander, both difficult to confirm. One record is of larvae from near Ottawa (although the locality information is questionable) and the other of larvae collected from a stream in the Niagara region in 1877. This salamander has not been reported in Ontario since then.

The Spring Salamander lives in the Appalachian region of eastern North America, ranging from southern Quebec to Georgia and Mississippi and west to West Virginia. In Canada it is now found only in Quebec.

Why it disappeared from Ontario

Due to the limited records in Ontario, historic threats cannot be determined.

Source: https://www.ontario.ca/page/spring-salamander

Photo Credit: Dave Huth

https://www.flickr.com/photos/davemedia/

0 notes