#florine of burgundy

Text

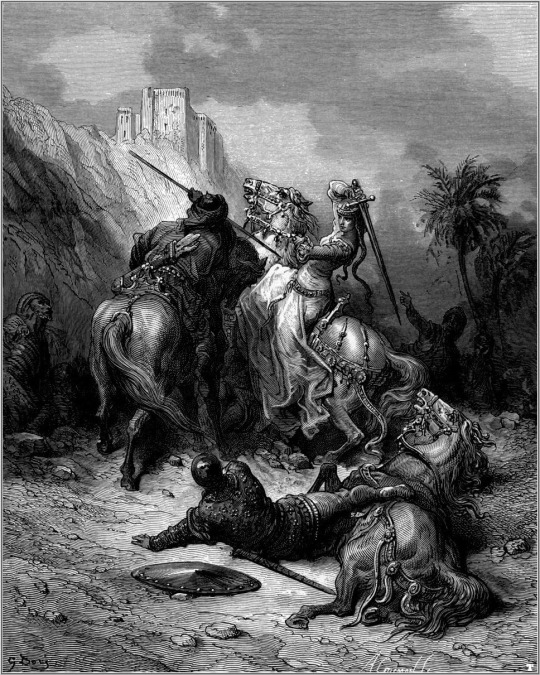

Florine of Burgundy by Gustave Doré

#florine of burgundy#art#gustave doré#heroine#first crusade#crusades#bibliothèque des croisades#history of the crusades#medieval#history#crusader#crusaders#warriors#philomelium#cappadocia#burgundy#princess#burgundian#the first crusade#middle ages#europe#french#illustration#engraving#romanticism#battle#central anatolia#anatolia#turkey#asia minor

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

FLORINE OF BURGUNDY // CRUSADER

“She was a French crusader, known for leading an army of 1,500 Danish knights onto a crusade with her husband, Sweyn the Crusader. However, they were ambushed by the Turks in Cappadocia, Anatolia, and were severely outnumbered. According to one tradition, the couple fought valiantly until Florine was pierced by 6 or 7 arrows.”

0 notes

Photo

It’s mothers’ day in France today, and my mom wanted a woman warrior in my last inktober style as a bookmark. So here’s Florine of Burgundy, a lady crusader who kept fighting after taking 7 arrows.

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Florine of Burgundy (1083-1097) fighting with the Turks

Florine was a daughter of Duke of Burgundy and married to a Danish prince Sweyn the Crusader. Together they were leading an army of 1500 men when ambushed by Turkish troops. The crusaders were heavily outnumbered and the contingent was wiped out.

An engraving by Gustave Dore (1832-1883)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(An imaginative depiction of Florine of Burgundy by Gustave Doré. According to Albert of Aix, Florine was killed during the First crusade while trying to escape the enemy mounted on a mule. She isn’t said to have fought, unlike what is stated on Wikipedia and other websites.)

Crusading women

Women formed an integral part of the crusading movement. Noblewomen traveled with their husbands, women went with the army and performed support functions. Some of them even took arms.

Mentions of fighting women start from the First crusade (1096-1099). During the Battle of Droylaeum in 1097, women risked their lives to bring water to the soldiers. William of Tyre reports that, during the siege of Jerusalem in 1099, “women, forgetful of their sex and unmindful of their inherent fragility, were presuming to take arms and fought manfully beyond their strength”. He wasn’t, however, an eyewitness and provides the only mention of these women. William of Tyre furthermore notes the presence of 6000 footmen of “both sexes” gathered in front of Nicaea. Dodequin, abbot of saint Disybode, gives a similar testimony, writing that among the people who left for the crusade in 1096 were armed women wearing male clothing. Some of them even brandished their own banners.

The Austrian margravine Ida of Cham (c.1055-1101) also led troops in battle during the crusade of 1101. Ida, who was reportedly one of the most beautiful women of her time, joined the crusaders at the head of her vassals. According to the monk Ekkehard of Aura, who took part in the expedition and interrogated survivors of the battle, Ida fell during an enemy attack.

Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, provided troops for the Second crusade (1147-1149). Byzantine chronicler Michael Choniates, though not a first-hand observer, notes the presence of a troop of women armed with lances and axes in the army of Conrad III of Germany. They were allegedly led by a richly adorned woman nicknamed “goldfoot”.

The Third crusade (1189–1192) provides an interesting case due to the contrast between the Muslim and Christian reports. In Christian accounts, women play a mostly supportive role. A woman was, for instance, struck by a dart while working to fill in a ditch at Acre and asked for her body to be added to the fill. Other women were said to have performed this role. Others were also said to have slaughtered enemy prisoners.

The Muslim accounts are somewhat different since they describe Christian women participating actively in the battle. Imad al-Din recorded for instance, that there were many female knights among the Christians, who were found out to be women only when stripped of their armor after their death. After an attack of the Christian army of Saladin’s camp on July 25 1190, Imad al-Din and Baha al-Din went together to examine the dead. Baha al-Din wrote: “I noticed the body of two women. Someone told me that he had seen four women engaged in the fight, of whom two were made prisoners”. Baha al-Din also notes the presence of women among the dead. They both mention a female archer among the Christian army at Acre in July 1191. The woman was said to have worn a green coat and killed a number of enemies. She nonetheless fell in battle and her bow was reportedly brought to Saladin who was greatly astonished. Ibn Al-Athîr reports that an anonymous woman distinguished herself during the siege of Bourzey castle in 1188, where she operated a mangonel and destroyed several enemy engines.

There is thus a stark contrast between the numerous Muslim testimonies and the silence of the Christian ones. The truth lies probably somewhere in between. The Muslim chroniclers highlight the presence of women to point out the unnaturalness of their foes while the Christians wanted first of all to enhance the virtue of the crusaders and regarded women’s presence as a threat to said virtue. Archeological discoveries nonetheless provide evidence of armored women. In 1982, the Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima unearthed the skeleton of a crusader wearing remnants of an armor comprised of bronze plates on a leather backing. The skeleton was afterward found to be the one of a woman and was thus dubbed the “Joan of Caesarea”.

A woman who found herself fighting in a desperate situation was sister Margaret of Beverley (c.1150- c.1215). Her story was recounted by her brother, the monk Thomas of Froidmont. In 1187, Margaret found herself on the walls of the besieged Jerusalem: “like a fierce virago, I tried to play the role of a man”. Wearing a breastplate and using a cauldron as a helmet, she went armed and brought water to the soldiers until she was hit by a flying stone. After the fall of the city, Margaret bought her freedom, but was ultimately captured and sold as slave until her freedom was finally bought by a Christian of Tyre.

Reports of the Fifth crusade (1217-1222), tell that during the siege of Damietta 1219, a woman gave the alert when the enemy tried to send troops and supplies to the city through the siege camp. The enemy soldiers were thus routed and killed. This woman was probably armed and on guard duty since everyone in the camp, including women and merchants, had to perform guard duty and had to carry weapons while doing so. An additional account tells that the fugitives were killed by the women of the camp.

Finally, it’s worth noting that French queen Margaret of Provence (1221-1295) assumed military command during the Seventh crusade (1248-1254) in 1250 after her husband was captured. Just after giving birth, she managed to prevent desertions and successfully negotiated her husband’s ransom.

At the end of the 17th century, French traveler and writer Maximilien Misson traveled in Italy and visited a Genoese arsenal. He saw there 32 suits of armor that were said to have been made for some ladies of the city who wished to go on a crusade in 1301. Finding the story hard to believe, he researched the archives and found three letters from Pope Boniface VIII that confirmed the story. Some women were of high-ranking families, others came from lesser nobility. The pope encouraged them and praised their incentives, saying that they “strengthened their arms with male actions”. A whole female battalion was supposed to take part in the expedition. The crusade didn’t take place due to the lack of participants and the sets of armor were sold in 1815.

Bibliography:

Cassagnes-Brouquet Sophie, Chevaleresses, une chevalerie au féminin

Eads Valerie, “Means, Motive, Opportunity: Medieval Women and the Recourse to Arms”

Faucherre Nicolas, Mesqui Jean, Prouteau Nicolas, “La fortification au temps des croisades”

Gay Louise, “Des commandements militaires féminins en guerre sainte: Marguerite de Provence et Sagar al-Durr lors de la septième croisade”

Hodgson Natasha S., Women, crusading and the holy land historical narrative

Nicholson Helen, “Women on the third crusade”

Rose Hager Katherine, Endowed with Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat

Sténuit Marie-Eve, Femmes en armes, les guerrières de l’histoire

#crusades#history#women in history#warrior women#middle ages#medieval history#11th century#12th century#13th century#Ida of Cham#genoese ladies#Joan of Caesarea#Margaret of Beverley#Margaret of provence#Eleanor of Aquitaine#war#women in war#women warriors#female soldiers

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

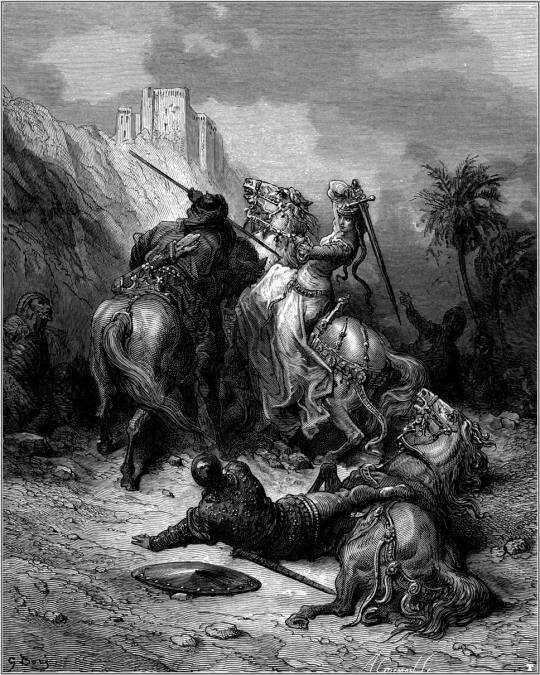

Women of the House of Burgundy aesthetic, part I

Constance, reina de León y de Castilla. Daughter of Robert Ier, duc de Bourgogne and Helie de Semur-en-Brionnais. Mother of Urraca I de León.

Hildegarde, duquessa d’Aquitània. Daughter of Robert Ier, duc de Bourgogne and Ermengarde-Blanche d’Anjou. Grandmother of Agnès d’Aquitània, reina d’Aragón. Great-grandmother of Alienòr d’Aquitània; Petronilha d’Aquitània, comtesse de Vermandois; and Peyronela d’Aragón.

Hélène, comtesse de Ponthieu. Daughter of Eudes Ier, duc de Bourgogne and Sibylle de Bourgogne. Ancestress of Isabel de Warenne, Countess of Surrey; Mélisende de Tripoli; Ela, 3rd Countess of Salisbury; and Jehanne de Dammartin, comtesse de Ponthieu.

Florine de Bourgogne. Daughter of Eudes Ier, duc de Bourgogne and Sibylle de Bourgogne.

Sibylle, regina di Sicilia. Daughter of Hugues II, duc de Bourgogne and Mathilde de Mayenne.

Mathilde, senhora de Montpelhièr. Daughter of Hugues II, duc de Bourgogne and Mathilde de Mayenne. Grandmother of Maria de Montpelhièr, reina d’Aragó.

Marguerite, contessa di Savoia. Daughter of Hugues III, duc de Bourgogne and Béatrice d’Albon, dauphine de Viennois. Grandmother of Costanza II di Sicilia.

Marguerite, vescomtessa de Lemòtges. Daughter of Hugues IV, duc de Bourgogne and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Maria de Lemòtges, dugez Breizh. Grandmother of Jehanne de Penthièvre, dugez Breizh.

Adélaïde, hertogin van Brabant. Daughter of Hugues IV, duc de Bourgogne and Yolande de Dreux. Mother of Maria van Brabant, reine de France.

#house of burgundy#historyedit#french history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today in history, May 4, 1471, The Battle of Tewkesbury:

"The Battle of Tewkesbury, which took place on 4 May 1471, was one of the decisive battles of the Wars of the Roses. The forces loyal to the House of Lancaster were completely defeated by those of the rival House of York under their monarch, King Edward IV. The Lancastrian heir to the throne, Edward, Prince of Wales, and many prominent Lancastrian nobles were killed during the battle or were dragged from sanctuary two days later and immediately executed. The Lancastrian king, Henry VI, who was a prisoner in the Tower of London, died or was murdered shortly after the battle. Tewkesbury restored political stability to England until the death of Edward IV in 1483.

The term, the Wars of the Roses, refers to the informal heraldic badges of the two rival houses of Lancaster and York which had been contending for power, and ultimately for the throne, since the late 1450s. In 1461 the Yorkist claimant, Edward, Earl of March, was proclaimed King Edward IV and defeated the supporters of the weak, intermittently insane Lancastrian king Henry VI at the Battle of Towton. Lancastrian revolts in the far north of England were defeated in 1464, and the fugitive King Henry was captured and imprisoned the next year. His Queen, Margaret of Anjou, and their thirteen-year-old son Edward of Westminster, were exiled and impoverished in France. Edward IV's hold on the throne appeared temporarily to be secure.

Edward IV owed his victory in large measure to the support of his cousin, the powerful Earl of Warwick. They became estranged when Edward spurned the French diplomatic marriage that Warwick was seeking for him and instead married Elizabeth Woodville, widow of an obscure Lancastrian gentleman, in secret in 1464. When the marriage became public knowledge, Edward placed many of his new queen's family in powerful positions that Warwick had hoped to control. Edward meanwhile reversed Warwick's policy of friendship with France by marrying his sister Margaret to Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy. The embittered Warwick secured the support of Edward IV's brother George, Duke of Clarence, for a coup, in exchange for Warwick's promise to crown Clarence king. Although Edward was imprisoned briefly, Clarence was unacceptable as monarch to most of the country. Edward was allowed to resume his rule, outwardly reconciled with Warwick and Clarence. Within a year, he accused them of fresh treachery and forced them to flee to France.

With no hope of a reconciliation with King Edward, Warwick's best hope of regaining power in England lay in restoring Henry VI to the throne. Louis XI of France feared a hostile alliance of Burgundy under Charles the Bold and England under Edward. He was prepared to support Warwick with men and money, but to give legitimacy to any uprising by Warwick, the acquiescence of Margaret of Anjou was required. Warwick and Margaret were previously sworn enemies, but Margaret's attendants (in particular Sir John Fortescue, formerly Chief Justice during Henry VI's reign) and Louis eventually persuaded her to ally the House of Lancaster with Warwick. At Angers, Warwick begged her pardon on his knees for all past wrongs done to her, and was forgiven. Prince Edward was betrothed to Warwick's younger daughter Anne. (The marriage was eventually solemnised at Amboise on 13 December 1470 but may not have been consummated, as Margaret was seeking a better match for Edward once he was King.) Finally, they swore loyalty to Henry VI on a fragment of the True Cross in Angers Cathedral. However, Margaret declined to let Prince Edward land in England or to land there herself until Warwick had established a firm government and made the country safe for them.

Warwick landed in the West Country on 13 September 1470, accompanied by Clarence and some unswerving Lancastrian nobles, including the Earl of Oxford and Jasper Tudor, the Earl of Pembroke. As King Edward made his way south to face Warwick, he realised that Warwick's brother John, Marquess of Montagu, who had up till then remained loyal to Edward, had defected at the head of a large army in the North of England. Edward fled to King's Lynn where he took ship for Flanders, part of Burgundy, accompanied only by his youngest brother, Richard of Gloucester, and a few faithful adherents.

In London, Warwick released King Henry, led him in procession to Saint Paul's cathedral and installed him in Westminster palace. Warwick's position nevertheless remained precarious. His alliance with Louis of France and his intention to declare war on Burgundy was contrary to the interests of the merchants, as it threatened English trade with Flanders and the Netherlands. Clarence had long been excluded from Warwick's calculations. In November 1470, Parliament declared that Prince Edward and his descendants were Henry's heirs to the throne; Clarence would become King only if the Lancastrian line of succession failed. Unknown to Warwick, Clarence secretly became reconciled with his brother, King Edward.

With Warwick in power in England, it was Charles of Burgundy's turn to fear a hostile alliance of England and France. As an obvious counter to Warwick, he supplied King Edward with money (50,000 florins), ships and several hundred men (including handgunners). Edward set sail from Flushing on 11 March 1471 with 36 ships and 1200 men. He touched briefly on the English coast at Cromer but found that the Duke of Norfolk, who might have supported him, was away from the area and that Warwick controlled that part of the country. Instead, his ships made for Ravenspurn, near the mouth of the River Humber, where Henry Bolingbroke had landed in 1399 on his way to reclaim the Duchy of Lancaster and ultimately depose Richard II.

Edward's landing was inauspicious at first; the ships were scattered by bad weather and his men landed in small detachments over a wide area on 14 March. The port of Kingston-upon-Hull refused to allow Edward to enter, so he made for York, claiming rather like Bolingbroke that he was seeking only the restoration of the Duchy of York. He then began to march south. Near Pontefract Castle he evaded the troops of Warwick's brother Montagu. By the time Edward reached the city of Warwick, he had gathered enough supporters to proclaim himself King again. The Earl of Warwick sent urgent requests for Queen Margaret, who was gathering fresh forces in France, to join him in England. He himself was at Coventry, preparing to bar Edward's way to London, while Montagu hastened up behind the King's army.

Edward however, knew that Clarence was ready to turn his coat once again and betray Warwick, his father-in-law. He marched rapidly west and joined with Clarence's men who were approaching from Gloucestershire. Clarence appealed to Warwick to surrender, but Warwick refused to even speak to him. Edward's army made rapidly for London, pursued by Warwick and Montagu. London was supposedly defended by the 4th Duke of Somerset, but he was absent and the city readily admitted Edward. The unfortunate and by now feeble Henry VI was sent back to the Tower of London. Edward then turned about to face Warwick's approaching army. On 14 April, they met at the Battle of Barnet. In a confused fight in thick fog, some of Warwick's army attacked each other by mistake and at the cries of "Treachery!" his army disintegrated and was routed. Montagu died in the battle, and Warwick was cut down trying to reach his horse to escape.

Urged on by Louis XI, Margaret had finally sailed on 24 March. Storms forced her ships back to France several times, and she and Prince Edward finally landed at Weymouth in Dorsetshire on the same day that the Battle of Barnet was fought. While Margaret sheltered at nearby Cerne Abbey, the Duke of Somerset brought news of the disaster at Barnet to her. She briefly wished to return to France, but Prince Edward persuaded her to gamble for victory. Somerset and the Earl of Devon had already raised an army for Lancaster in the West Country. Their best hope was to march northwards and join forces with the Lancastrians in Wales, led by Jasper Tudor. Other Lancastrian forces could be relied upon to distract King Edward; in particular, a fleet under Warwick's relation, the Bastard of Fauconberg, was preparing to descend on Kent where the Nevilles and Warwick in particular had always been popular.

In London, King Edward had learned of Margaret's landing only two days after she arrived. Although he had given many of his supporters and troops leave after the victory at Barnet, he was rapidly able to muster a substantial force at Windsor, just west of London. It was difficult at first to determine Margaret's intentions, as the Lancastrians had sent out several feints which suggested that they might be making directly for London, but Edward's army set out for the West Country within a few days.

On 30 April, Margaret's army had reached Bath, on its way towards Wales. She turned aside briefly to secure guns, reinforcements and money from the city of Bristol. On the same day, King Edward reached Cirencester. On hearing that Margaret was at Bristol, he turned south to meet her army. However, the Lancastrians made a feint towards Little Sodbury, about 12 miles (19 km) north-east of Bristol. Nearby was Sodbury Hill, an Iron Age hill fort which was an obvious strategic point for the Lancastrians to seize. When Yorkist scouts reached the hill, there was a sharp fight in which they suffered heavy casualties. Believing that the Lancastrians were about to offer battle, Edward temporarily halted his army while the stragglers caught up and the remainder could rest after their rapid march from Windsor. However, the Lancastrians instead made a swift move north by night, passing within 3 miles (4.8 km) of Edward's army. By the morning of 2 May, they had gained the safety of Berkeley Castle and had a head start of 15 miles (24 km) over Edward.

King Edward realised that the Lancastrians were seeking to cross the River Severn into Wales. The nearest crossing point they could use was at the city of Gloucester. He sent urgent messages to the Governor, Sir Richard Beauchamp, ordering him to bar the gates to Margaret and man the city's defences. When Margaret arrived in the morning of 3 May, Beauchamp refused Margaret's summons to let her army pass, and she realised that there was insufficient time to storm the city before Edward's army arrived. Instead, her army made another forced march of 10 miles (16 km) to Tewkesbury, attempting to reach the next bridge at Upton-upon-Severn, 7 miles (11 km) further on. Edward meanwhile had marched no less than 31 miles (50 km), passing through Cheltenham (then little more than a village) in the late afternoon. The day was very hot, and both the Lancastrians and Edward's pursuing army became exhausted. The Lancastrians were forced to abandon some of their artillery, which was captured by Yorkist reinforcements following from Gloucester.

At Tewkesbury, the tired Lancastrians halted for the night. Most of their army were footmen, and unable to continue further without rest, and even the mounted troops were weary. By contrast, King Edward's army was composed mainly of mounted men, who nevertheless dismounted to fight on foot as most English armies did during this period. Hearing from his "prickers" or mounted scouts of Margaret's position, Edward drove his army to make another march of 6 miles (9.7 km) from Cheltenham, finally halting 3 miles (4.8 km) from the Lancastrians. The Lancastrians knew they could retreat no further before Edward attacked their rear, and that they would be forced to give battle.

As day broke on 4 May, the Lancastrians took up a defensive position a mile south of the town of Tewkesbury. To their rear were River Avon and the Severn. Tewkesbury Abbey was just behind the Lancastrian centre. A farmhouse then known as Gobes Hall marked the centre of the Lancastrian position; nearby was "Margaret's camp", earthworks of uncertain age. Queen Margaret is said to have spent the night at Gobes Hall, before hastily taking refuge on the day of battle in a religious house some distance from the battlefield. The main strength of the Lancastrians' position was provided by the ground in front, which was broken up by hedges, woods, embankments and "evil lanes". This was especially true on their right.

The Lancastrian army numbered approximately 6,000. As was customary at the time, it was organised into three "battles". The right battle was commanded by the Duke of Somerset. A stream, the Colnbrook, flowed through his position, making some of the ground difficult to traverse. The Lancastrian centre was commanded by Lord Wenlock. Unlike the other principal Lancastrian commanders, Wenlock had deserted the Lancastrian cause after the First Battle of Saint Albans, only to revert to the Lancastrians when he was deprived of the Lieutenancy of Calais. Prince Edward was present with the centre. At seventeen, Prince Edward was no stranger to battlefields, having been given by his mother the task of condemning to death Yorkist prisoners taken at the Second Battle of St Albans, but he lacked experience of actual command. The left battle was commanded by the Earl of Devon, another devoted Lancastrian. His battle, and part of the centre, occupied a low ridge known locally as the "Gastons". A small river, the Swilgate, protected Devon's left flank, before curving behind the Lancastrian position to join the Avon.

The Yorkists numbered 5,000 and were slightly outnumbered by the Lancastrians. Like the Lancastrians, King Edward organised his army into three battles.

Edward's vanguard was commanded by his youngest brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Although he was only eighteen years old, Richard was already an experienced commander and had led a division at the Battle of Barnet. Edward himself commanded the main battle, in which Clarence was also stationed. Edward was twenty-nine years old, and at the height of his prowess as a soldier. His lifelong friend and supporter, Lord Hastings, commanded the rear. He too was an experienced commander and like Richard, had accompanied Edward into exile in the Low Countries and had led a battle at Barnet.

Although by tradition, the vanguard occupied the right of the line of battle, several authors have conjectured from descriptions in near-contemporary accounts (such as the Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV) that Richard of Gloucester's division actually took position to the left of Edward's battle or that the divisions of Edward's army advanced in line ahead, with Edward's division leading.

Edward made one other important tactical disposition. To the left of his army was a thickly wooded park. Concerned that hidden Lancastrians might attack from this quarter, he ordered 200 mounted spearmen to occupy part of the woods and prevent the Lancastrians making use of them, or act on their own initiative if they were not themselves attacked. He then "displayed his bannars: dyd blowe up the trompets: commytted his caws and qwarell to Almyghty God, to owr most blessyd lady his mother: Vyrgyn Mary, the glorious Seint George, and all the saynts: and advaunced, directly upon his enemyes."

As they moved towards the Lancastrian position, King Edward's army found that the ground was so broken up by woods, ditches and embankments that it was difficult to attack in any sort of order. However, the Yorkist archers and artillery showered the Lancastrians with arrows and shot. The Yorkists certainly had more guns than their enemies, and they were apparently better served.

Either to escape the cannonade and volleys of archery or because he saw an opportunity to outflank King Edward's isolated battle, the Duke of Somerset led at least part of his men via some of the "evil lanes" to attack Edward's left flank. Although taken by surprise, Edward's men resisted stoutly, beating back Somerset's attack among the hedges and banks. At the vital moment, the 200 spearmen Edward had earlier posted in the woods far out on the left attacked Somerset from his own right flank and rear, as Gloucester's battle also joined in the fighting.

Somerset's battle was routed, and his surviving army tried to escape across the Severn. Most were cut down as they fled. The long meadow astride the Colnbrook leading down to the river is known to this day as "Bloody Meadow". Somerset galloped up to Wenlock, commanding the centre, and demanded to know why Wenlock had failed to support him. According to legend (recounted in Edward Hall's chronicle, written several years afterwards though from first-hand accounts), he did not wait for an answer but dashed out Wenlock's brains with a battleaxe before seeking sanctuary in the Abbey.

As its morale collapsed, the rest of the Lancastrian army tried to flee, but the Swilgate became a deadly barrier. Many who succeeded in crossing it converged on a mill south of the town of Tewkesbury and a weir in the town itself, where there were crossings over the Avon. Here too, many drowned or were killed by their pursuers.

Among the leading Lancastrians who died on the field were Somerset's younger brother John Beaufort, Marquess of Dorset, and the Earl of Devon. The Prince of Wales was found in a grove by some of Clarence's men. He was summarily executed, despite pleading for his life to Clarence, who had sworn allegiance to him in France barely a year before.

Many of the other Lancastrian nobles and knights sought sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. King Edward attended prayers in the Abbey shortly after the battle. He granted permission for the Prince of Wales and others slain in the battle to be buried within the Abbey or elsewhere in the town without being quartered as traitors as was customary. However, two days after the battle, Somerset and other leaders were dragged out of the Abbey, and were ordered by Gloucester and the Duke of Norfolk to be put to death after perfunctory trial. Among them were Hugh Courtenay, younger brother of the Earl of Devon, and Sir John Langstrother, the prior of the military order of St. John. The Abbey was not officially a sanctuary, though it is doubtful whether this would have deterred Edward even if it had been. It had to be reconsecrated a month after the battle, following the violence done within its precincts.

A few days later, Margaret sent word to Edward from her refuge that she was "at his commandment"."

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Street Rod of the Year! Street Rodder’s Top Pick for 2018 Plus 10 Runners-Up

And the winner is … Bob Florine’s 1957 Ford Del Rio Ranch Wagon.

Award winners in the 2018 STREET RODDER Top 100 program, sponsored by Painless Performance Products, were selected at Cruisin’ The Coast 2017, Grand National Roadster Show, Sacramento Autorama, Detroit Autorama, Back to the 50’s, Syracuse Nationals, NSRA Street Rod Nationals (outdoor), NSRA Street Rod Nationals (indoor), Hot August Nights, and the Danchuk Tri-Five Nationals. From those 100 vehicles, we selected Bob’s completely custom 1957 Ford wagon as the 2018 Street Rod of the Year, along with 10 runners-up.

1957 Ford Del Rio Ranch Wagon | Bob Florine | Ventura, CA

STREET RODDER had been monitoring the progress on Bob Florine’s remarkable wagon since its early stages and gave it a Top 100 pick at the Grand National Roadster Show. Steve Strope and his crew at Pure Vision in Simi Valley, California, handled the overall creation, starting with Steve Stanford’s concept artwork. Mick Jenkins handled much of the sheetmetal modification, bodywork, and paintwork. The numerous exterior mods include lengthened doors and slanted B-pillars, and a 1959 Thunderbird hood scoop. The raised rear wheel openings show off custom Billet Specialties wheels. The two-tone paint combines PPG Ferrari Avorio and Aston Martin Bridgewater Bronze.

A mandrel-bent frame forms the platform for the Art Morrison Enterprises custom chassis, which uses C6 ZR1-based IFS components. The rear features a Speedway Engineering 9-inch with Mike Maier rear torque arms and JRI coilovers.

Bob fulfilled his wish for a shotgun engine with a 700-plus horsepower Jon Kaase Racing Boss9 stroker engine topped with a Borla eight-stack injection system with a FAST controller. The Hughes Performance 4L80E transmission uses a Gear Vendors under/overdrive unit.

Gabe Lopez at Gabe’s Street Rod Custom Interiors covered the insides with two-tone Italian leather with woven leather seat inserts. A custom-built Redline Gauge Works instrument cluster fills the dash. The upper dash speaker grille lifts to reveal a Bluetooth-equipped iPad.

Congratulations to Bob Florine and Steve Strope at Pure Vision for this amazing 1957 Ford wagon, our 2018 Street Rod of the Year. Read more details and see more than 50 photos at https://bit.ly/2OtDWeq.

1933 Ford Coupe | Dennis Mariani Jr. | Oakland, CA

The Mariani Brothers coupe, built by Steve Moal of Moal Coachbuilders in Oakland, California, is another Top 100 winner from the Grand National Roadster Show. Dennis Mariani Jr. wanted a high-end, classy, street driven coupe to reflect the look of the land speed cars he and his family have raced on the salt flats. The track nose, 3-1/2-inch chopped top, belly pans, PPG British Racing Green paint, hand-formed aluminum four-piece hood, and other elements accomplish that. A Hilborn EFI setup feeds the Dart aluminum Chevy small-block with Hilborn injection, based on a Panella Racing block. A Legend five-speed transmission delivers torque to the quick-change rear. A Moal torsion-bar suspension was built on the stock Ford frame, beefed up with tubular crossmembers. Moal custom knockoff caps distinguish the Stockton Wheel steelies with Excelsior tires. Sid Chavers stitched the beige and oxblood leather interior. For more photos and video of this car, visit https://bit.ly/2RBxnIy.

1957 Chevy Bel Air Two-Door Hardtop | Charles Baxley | Beech Island, SC

STREET RODDER’s Top 100 list for 2018 includes a whopping 20 Tri-Five Chevys, 10 of which were selected at the Danchuk Tri-Five Nationals (of course). This patent-leather black 1957 Bel Air was one of our favorites from Beech Bend Raceway, but was also selected by event judges as the Tri Five of the Year. Charles Baxley kept the exterior mods appropriately mild, saving the custom stuff for the rest of the car. The car rides on an Art Morrison Enterprises front suspension and a four-link and coilovers in the rear suspending a Ford 9-inch. The 18- and 20-inch Knuckle five-spoke wheels are from Billet Specialites’ Vintage series. A modified Chevy LS2 engine is backed by a 4L60E transmission. The superclean, mega-red interior includes modern bucket seats, and a contemporary redesign of a classic 1955 dash, filled with Dakota Digital analog gauges and vents for the Vintage Air A/C system.

1947 Cadillac Series 62 | Kevin Anderson | Indianapolis, IN

Kevin Anderson’s Crystal Cadillac knocked us out at the Detroit Autorama. Originally a four-door sedan, it moved from a Minneapolis museum to Gas Axe Garage in Allendale, Michigan, where Mike Boerema converted it to a coupe with 48-inch doors. A 5-inch chop and airbag suspension brings things low. The sedan windshield was reshaped to look like a convertible, with a Haartz cloth Carson-style top completing the look. Chromed sombrero hubcaps and wide whitewalls fill the front fenders; rear fender skirts are lowered and filled. Gary Brown at Brown’s Metal Mods sprayed the paint. The leather upholstery, contrasted by authentic ’40s Cadillac fabric inserts, was designed by Kevin and installed by Joe Bukrey at Buckskinz in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Door garnish moldings wear polished Crystal Cadillac badges. The original 47,000-mile 346 Cadillac flathead is backed by the original transmission. See more at https://bit.ly/2JK4yas.

1962 Ford Galaxie Convertible | Gary Gregory & Fred Graefe | Stewartstown, PA

Our 2017 SROY came from the indoor display cars at the NSRA Street Rod Nationals. In 2018, two of our runners-up were discovered outside. This 1962 Ford Galaxie convertible came from the factory with superclean lines that make a perfect platform for hot rodding. The transformation from factory to Top 100 winner took place in Stewartstown, Pennsylvania, home of Lucky 7 Rod Shop. The Axalta charcoal paint is contrasted by the cloth top and the modern front and rear bucket seats upholstered in burgundy leather. Gary and Fred chose Billet Specialties 18×8 and 20×10 wheels to complete the outer impression. Underhood the engine compartment is stuffed with a dual-turbocharged 5.0L Ford Coyote built to unleash close to 700 hp and backed by a 6R80 six-speed. Chassis goodies include the QA1 shocks at each corner and RideTech rear suspension parts. For more photos, visit https://bit.ly/2Qgk00e.

1932 Ford Coupe | Bret Sukert | Montesano, WA

Bret Sukert’s ’60s-style 1932 three-window coupe got our attention as soon as we entered the Suede Palace. This traditional hot rod is homebuilt from an unmodified original steel body bought from well-known rodder Dick Page. Foss’ Hot Rods handled body and paint chores before Mitch Kim stepped forward to add all that pinstriping. The suspension includes a dropped axle and transverse leafs in front and quarter ellipticals in back, built on a Deuce frame. The Chevy 350 small-block is topped with a Weiand manifold and 1965-1966 GTO air cleaner. Interior elements include Mopar van seats with white tuck ’n’ roll upholstery, an N.O.S. Grant wheel, a restored Ha Dees heater, and Stewart-Warner blue face gauges (it took 50 gauges to get eight that matched). The coupe left the Suede Palace with the Best of Show award as well as a Top 100 pick. See more photos at https://bit.ly/2AN9hFd.

1962 Chevy Impala | Jesse Lindberg | Redding, CA

At the Sacramento Autorama, Scott Bonowski (who’d won the America’s Most Beautiful Roadster award a month before) insisted that we take a close look at Jesse Lindberg’s Impala. Jesse found the car in pieces, scattered all over, and built it at his automotive repair shop. He competes in Sound Quality contests, but the high-end audio system is only one of many impressive parts. Two-tone gold and green paint finish a body modified with subtle mods. Raceline 19- and 20-inch wheels fill the fenders. A carbureted Chevy Vortec 350 engine and 700-R4 trans move the Impala down the street, with airbags and CPP shocks ironing out the ride. Inside, tan leather upholstery is paired with vintage cloth inserts. The top-shelf stereo components hidden in the trunk are heard but not seen. We’ll have a full article in a future issue. For now, check out https://bit.ly/2PbyCkV for a few more photos.

1934 Ford Pickup | Danielle Lutz | Moscow, PA

Danielle Lutz’s channeled and chopped hot rod pickup, built by Jason Graham Hot Rods in Portland, Tennessee, earned its Top 100 pick at its Detroit Autorama debut. Jason treated the truck cab to a 1-1/2-inch stretch and 4-1/2-inch chop with slanted A-pillars—and added flush-fit doors, a custom hood, grille insert, and bed sides—before spraying the traditional Washington Blue paint. The chassis is traditional too, with a straight axle, front and rear split wishbones, quarter-elliptic springs, and exposed Winters quick-change rear. Excelsior rubber wraps 18- and 20-inch custom wheels. An Inglese eight-stack setup delivers gas and air, and a big shot of vintage coolness, to the stroked 347 Ford small-block. The engine is paired with a TREMEC five-speed. Danielle’s truck went to Gil Vigil of Speed & Design for a complete custom interior, featuring deep tan relicate leather covering the custom buckets. For more, visit https://bit.ly/2JK4yas.

1956 Ford Victoria | Bruce & Judy Ricks | Sapulpa, OK

The classic looks of Bruce and Judy Ricks’ 1956 Victoria have been subtly altered by a 4-3/4-inch wedge section. Schott Performance wheels are covered in fat Pirelli rubber. A look inside reveals custom buckets covered in two-tone brown leather. The Vicky is a driver and an Art Morrison Sport IFS chassis, Strange-equipped 9-inch with a triangulated four-bar, and RideTech shocks contribute to its great ride. A look inside reveals Wise Guys bucket seats, covered in two-tone brown leather by Gabe’s Custom Interiors. A Ford Racing 427-inch small-block is fed by Autotrend eight-stack EFI and backed with a TREMEC T56 Magnum six-speed mixing the gears. Bruce worked with Steve Cook Creations in Oklahoma City, who had teamed up with Bruce on a 1956 Ford convertible; a Ridler award was the result. The Victoria won its Top 100 prize at the Street Rod Nationals. Read the full feature at https://bit.ly/2D85Fz4.

1934 Ford Roadster | Dale Fode | Redwood City, CA

In 2015, Dale Fode’s roadster was at the Grand National Roadster Show vying for America’s Most Beautiful Roadster. In 2018, it was at Hot August Nights winning a Top 100 award. The stunning street rod, virtually hand built by Mark Willis and Bob Stewart at Mark Willis Custom Painting in Grants Pass, Oregon, blends street rod attitude with ’30s coachbuilt car elegance. The jet black body has been widened, quarters moved up, and doors lengthened 6 inches. The 1935 fenders were fabricated—and cover 18- and 20-inch one-off wheels. The custom frame is the platform for the Kugel Komponents independent suspension. Gabe’s Custom Interiors wrapped the seats and doors in deep red leather. The custom components have the appearance of vintage pieces, surrounded by modern design throughout—from dash to door panels. There’s nothing nostalgic in the engine compartment, home to a Magnuson supercharged LS7. See more of Dale’s roadster at https://bit.ly/2F8eQ5l.

1965 GMC Fenderside Pickup | Jim Connerley | Carmichael, CA

Jim Connerley says his father bought the GMC new and wouldn’t have understood his goals for the truck. Jeff Norene at Lee’s Vintage Car Shop in West Sacramento, California, understood them well, transforming Jim’s GMC from a stocker to the showstopper that got a Top 100 pick at the Sacramento Autorama. With a few exceptions (like 1937 taillights, oak bed floor, and a custom rear pan), the exterior is stock. Metallic brown paint is dressed up with pinstriping and gold leaf lettering. American Racing wheels were painted to match. Rex Hutchison Racing built the Vortech supercharged LS engine. A full chassis from Scott’s Hot Rods includes a tubular frame, IFS components, Aldan coilovers, and Ford 9-inch. Jack’s Upholstery used butterscotch vinyl on the 2005 Chevy pickup bench. Jim’s GMC will appear in Classic Trucks magazine soon. Until then, enjoy photos and video at��https://bit.ly/2F2HogF.

The post Street Rod of the Year! Street Rodder’s Top Pick for 2018 Plus 10 Runners-Up appeared first on Hot Rod Network.

from Hot Rod Network https://www.hotrod.com/articles/street-rod-year-street-rodders-top-pick-2018-plus-10-runners/

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Florine of Burgundy (1083-1097) was a French princess and a famous participant in the First Crusade.

Florine was a princess of the Duchy of Burgundy, a vassal state of the Kingdom of France. As a teenager she was married to the Danish prince, Sweyn the Crusader, with whom she set out with an army of 1500 Danish horsemen to join the First Crusade. While leading their army at a fast pace across the plains of Cappadocia they were ambushed by Turkish forces which overwhelmed them.

Florine and Sweyn were forced to defend themselves in a prolonged combat for a whole day, while the entirety of their army was slain around them. Florine sustained a number of arrow wounds but the two continued fight their way to safety in the nearby mountains. However they eventually succumbed to their attackers and died in battle. Florine was 14 years old.

Florine's life was later dramatised by William Bernard McCabe in the novel Florine, Princess of Burgundy.

#Florine of Burgundy#princess florine#female soldiers#female rulers#women in war#history#French history#women's history#Burgundy#Cappadocia#The Crusades#First Crusade#Turkish history#William Bernard McCabe

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOMEN’S HISTORY † FLORINE DE BOURGOGNE (1083 – 1097)

Florine de Bourgogne was a daughter of Eudes Ier, duc de Bourgogne and Sibylle de Bourgogne, the daughter of Guillaume Ier, comte de Bourgogne.

Florine married Svend Korsfarer, the son of the king of Denmark, Svend Estridsen. Svend and Florine went on the First Crusade as leaders of the Danish knights. They were attacked by the Turks on the plains of Cappadocia and defended themselves for an entire day before they were overwhelmed and killed on the field of battle.

#florine of burgundy#house of burgundy#french history#danish history#european history#asian history#women's history#history#women's history graphics#nanshe's graphics

130 notes

·

View notes