#financial engineering

Text

No, Uber's (still) not profitable

Going to Defcon this weekend? I'm giving a keynote, "An Audacious Plan to Halt the Internet's Enshittification and Throw it Into Reverse," on Saturday at 12:30pm, followed by a book signing at the No Starch Press booth at 2:30pm!

https://info.defcon.org/event/?id=50826

Bezzle (n):

1. "the magic interval when a confidence trickster knows he has the money he has appropriated but the victim does not yet understand that he has lost it" (JK Gabraith)

2. Uber.

Uber was, is, and always will be a bezzle. There are just intrinsic limitations to the profits available to operating a taxi fleet, even if you can misclassify your employees as contractors and steal their wages, even as you force them to bear the cost of buying and maintaining your taxis.

The magic of early Uber – when taxi rides were incredibly cheap, and there were always cars available, and drivers made generous livings behind the wheel – wasn't magic at all. It was just predatory pricing.

Uber lost $0.41 on every dollar they brought in, lighting $33b of its investors' cash on fire. Most of that money came from the Saudi royals, funneled through Softbank, who brought you such bezzles as WeWork – a boring real-estate company masquerading as a high-growth tech company, just as Uber was a boring taxi company masquerading as a tech company.

Predatory pricing used to be illegal, but Chicago School economists convinced judges to stop enforcing the law on the grounds that predatory pricing was impossible because no rational actor would choose to lose money. They (willfully) ignored the obvious possibility that a VC fund could invest in a money-losing business and use predatory pricing to convince retail investors that a pile of shit of sufficient size must have a pony under it somewhere.

This venture predation let investors – like Prince Bone Saw – cash out to suckers, leaving behind a money-losing business that had to invent ever-sweatier accounting tricks and implausible narratives to keep the suckers on the line while they blew town. A bezzle, in other words:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/19/fake-it-till-you-make-it/#millennial-lifestyle-subsidy

Uber is a true bezzle innovator, coming up with all kinds of fairy tales and sci-fi gimmicks to explain how they would convert their money-loser into a profitable business. They spent $2.5b on self-driving cars, producing a vehicle whose mean distance between fatal crashes was half a mile. Then they paid another company $400 million to take this self-licking ice-cream cone off their hands:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/09/herbies-revenge/#100-billion-here-100-billion-there-pretty-soon-youre-talking-real-money

Amazingly, self-driving cars were among the more plausible of Uber's plans. They pissed away hundreds of millions on California's Proposition 22 to institutionalize worker misclassification, only to have the rule struck down because they couldn't be bothered to draft it properly. Then they did it again in Massachusetts:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/15/simple-as-abc/#a-big-ask

Remember when Uber was going to plug the holes in its balance sheet with flying cars? Flying cars! Maybe they were just trying to soften us up for their IPO, where they advised investors that the only way they'd ever be profitable is if they could replace every train, bus and tram ride in the world:

https://48hills.org/2019/05/ubers-plans-include-attacking-public-transit/

Honestly, the only way that seems remotely plausible is when it's put next to flying cars for comparison. I guess we can be grateful that they never promised us jetpacks, or, you know, teleportation. Just imagine the market opportunity they could have ascribed to astral projection!

Narrative capitalism has its limits. Once Uber went public, it had to produce financial disclosures that showed the line going up, lest the bezzle come to an end. These balance-sheet tricks were as varied as they were transparent, but the financial press kept falling for them, serving as dutiful stenographers for a string of triumphant press-releases announcing Uber's long-delayed entry into the league of companies that don't lose more money every single day.

One person Uber has never fooled is Hubert Horan, a transportation analyst with decades of experience who's had Uber's number since the very start, and who has done yeoman service puncturing every one of these financial "disclosures," methodically sifting through the pile of shit to prove that there is no pony hiding in it.

In 2021, Horan showed how Uber had burned through nearly all of its cash reserves, signaling an end to its subsidy for drivers and rides, which would also inevitably end the bezzle:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/10/unter/#bezzle-no-more

In mid, 2022, Horan showed how the "profit" Uber trumpeted came from selling off failed companies it had acquired to other dying rideshare companies, which paid in their own grossly inflated stock:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/05/a-lousy-taxi/#a-giant-asterisk

At the end of 2022, Horan showed how Uber invented a made-up, nonstandard metric, called "EBITDA profitability," which allowed them to lose billions and still declare themselves to be profitable, a lie that would have been obvious if they'd reported their earnings using Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP):

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/11/bezzlers-gonna-bezzle/#gryft

Like clockwork, Uber has just announced – once again – that it is profitable, and once again, the press has credulously repeated the claim. So once again, Horan has published one of his magisterial debunkings on Naked Capitalism:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2023/08/hubert-horan-can-uber-ever-deliver-part-thirty-three-uber-isnt-really-profitable-yet-but-is-getting-closer-the-antitrust-case-against-uber.html

Uber's $394m gains this quarter come from paper gains to untradable shares in its loss-making rivals – Didi, Grab, Aurora – who swapped stock with Uber in exchange for Uber's own loss-making overseas divisions. Yes, it's that stupid: Uber holds shares in dying companies that no one wants to buy. It declared those shares to have gained value, and on that basis, reported a profit.

Truly, any big number multiplied by an imaginary number can be turned into an even bigger number.

Now, Uber also reported "margin improvements" – that is, it says that it loses less on every journey. But it didn't explain how it made those improvements. But we know how the company did it: they made rides more expensive and cut the pay to their drivers. A 2.9m ride in Manhattan is now $50 – if you get a bargain! The base price is more like $70:

https://www.wired.com/story/uber-ceo-will-always-say-his-company-sucks/

The number of Uber drivers on the road has a direct relationship to the pay Uber offers those drivers. But that pay has been steeply declining, and with it, the availability of Ubers. A couple weeks ago, I found myself at the Burbank train station unable to get an Uber at all, with the app timing out repeatedly and announcing "no drivers available."

Normally, you can get a yellow taxi at the station, but years of Uber's predatory pricing has caused a drawdown of the local taxi-fleet, so there were no taxis available at the cab-rank or by dispatch. It took me an hour to get a cab home. Uber's bezzle destroyed local taxis and local transit – and replaced them with worse taxis that cost more.

Uber won't say why its margins are improving, but it can't be coming from scale. Before the pandemic, Uber had far more rides, and worse margins. Uber has diseconomies of scale: when you lose money on every ride, adding more rides increases your losses, not your profits.

Meanwhile, Lyft – Uber's also-ran competitor – saw its margins worsen over the same period. Lyft has always been worse at lying about it finances than Uber, but it is in essentially the exact same business (right down to the drivers and cars – many drivers have both apps on their phones). So Lyft's financials offer a good peek at Uber's true earnings picture.

Lyft is actually slightly better off than Uber overall. It spent less money on expensive props for its long con – flying cars, robotaxis, scooters, overseas clones – and abandoned them before Uber did. Lyft also fired 24% of its staff at the end of 2022, which should have improved its margins by cutting its costs.

Uber pays its drivers less. Like Lyft, Uber practices algorithmic wage discrimination, Veena Dubal's term describing the illegal practice of offering workers different payouts for the same work. Uber's algorithm seeks out "pickers" who are choosy about which rides they take, and converts them to "ants" (who take every ride offered) by paying them more for the same job, until they drop all their other gigs, whereupon the algorithm cuts their pay back to the rates paid to ants:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

All told, wage theft and wage cuts by Uber transferred $1b/quarter from labor to Uber's shareholders. Historically, Uber linked fares to driver pay – think of surge pricing, where Uber charged riders more for peak times and passed some of that premium onto drivers. But now Uber trumpets a custom pricing algorithm that is the inverse of its driver payment system, calculating riders' willingness to pay and repricing every ride based on how desperate they think you are.

This pricing is a per se antitrust violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act, America's original antitrust law. That's important because Sherman 2 is one of the few antitrust laws that we never stopped enforcing, unlike the laws banning predator pricing:

https://ilr.law.uiowa.edu/sites/ilr.law.uiowa.edu/files/2023-02/Woodcock.pdf

Uber claims an 11% margin improvement. 6-7% of that comes from algorithmic price discrimination and service cutbacks, letting it take 29% of every dollar the driver earns (up from 22%). Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi himself says that this is as high as the take can get – over 30%, and drivers will delete the app.

Uber's food delivery service – a baling wire-and-spit Frankenstein's monster of several food apps it bought and glued together – is a loser even by the standards of the sector, which is unprofitable as a whole and experiencing an unbroken slide of declining demand.

Put it all together and you get a picture of the kind of taxi company Uber really is: one that charges more than traditional cabs, pays drivers less, and has fewer cars on the road at times of peak demand, especially in the neighborhoods that traditional taxis had always underserved. In other words, Uber has broken every one of its promises.

We replaced the "evil taxi cartel" with an "evil taxi monopolist." And it's still losing money.

Even if Lyft goes under – as seems inevitable – Uber can't attain real profitability by scooping up its passengers and drivers. When you're losing money on every ride, you just can't make it up in volume.

Image: JERRYE AND ROY KLOTZ MD (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LA_BREA_TAR_PITS,_LOS_ANGELES.jpg

CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

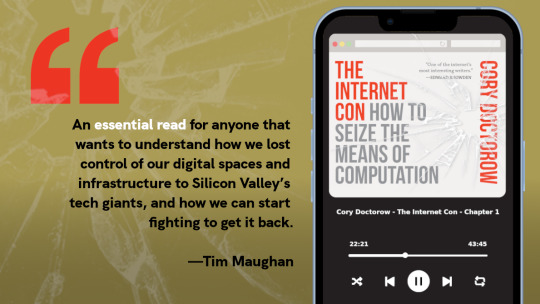

I’m kickstarting the audiobook for “The Internet Con: How To Seize the Means of Computation,” a Big Tech disassembly manual to disenshittify the web and bring back the old, good internet. It’s a DRM-free book, which means Audible won’t carry it, so this crowdfunder is essential. Back now to get the audio, Verso hardcover and ebook:

http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/09/accounting-gimmicks/#unter

Image:

JERRYE AND ROY KLOTZ MD (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LA_BREA_TAR_PITS,_LOS_ANGELES.jpg

CC BY-SA 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#bezzles#hubert horan#uber#rideshare#accounting tricks#financial engineering#late-stage capitalism#narrative capitalism#lyft#transit#uber eats#venture predation#algorithmic wage discrimination

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

vimeo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANALYSIS: How Herbert Wigwe Led Access Bank To Become A Surprising Financial Heavyweight

This analysis looks at one tool that Herbert Wigwe used to turn a relatively unknown Access Bank into reckoning in Nigeria and into a global brand. Under the visionary leadership of Herbert Wigwe, Access Bank has emerged as one of Africa’s most respected and recognizable financial institutions through an uncanny acquisition strategy. Beginning with the audacious acquisition of the formerly larger…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Residential solar has always faced a big impediment to growth: installing and maintaining solar panels is expensive, and few consumers wanted to spend tens of thousands of dollars in cash to pay upfront for what was a relatively untested product. To get around this problem, a company called SolarCity came up with a new model in the early 2010s—leasing solar panels to customers, allowing them to pay little to no upfront cost.

…

SolarCity’s other innovation was to package together thousands of consumer leases and sell them to investors as asset-backed securities [ABS], which enabled the company … to move debt off their balance sheet. … However, these financial innovations also increased the pressure on companies to grow quickly. Solar companies needed lots of new customers in order to package the loans into ABS and sell them to investors.

…

SolarCity ran out of money in 2016 and was acquired by Tesla, but the problems created by its expensive model have persisted. … Even today, about one-third of the upfront cost of a residential solar system goes to intermediaries like sales and financing people, says Pol Lezcano, an analyst with Bloomberg New Energy Finance. In Germany, where installation is done locally and there are fewer intermediaries, the typical residential system costs about 50% less than it costs in the U.S. “The upfront cost of these systems is stupidly high,” says Lezcano, making residential solar not “scalable.”

So a scheme originally aimed at reducing upfront costs actually ends up doing the opposite. Nice.

In some ways, the current situation in the residential solar market is analogous to the subprime lending crisis that set off the Great Recession, though on a smaller scale. Like in the subprime lending crisis, some companies issued loans to people who could not—or would not—pay them. Like in the subprime lending crisis, thousands of these loans—and in solar’s case, also leases—were packaged and sold to investors as asset-backed securities with promised rates of return. The Great Recession was driven largely by the fact that people stopped paying their loans, and the asset-backed securities didn’t deliver the promised rate of return to investors. Similar cracks may be forming in the solar ABS market.

Yowza.

#solar panels#solar energy#solar power#SolarCity#asset-backed securities#financialization#financial engineering

1 note

·

View note

Link

Learn more about interesting data analysis Stefan has done during past historical events and how it can help you think differently about what is going on in the economy today.

Stefan is the Founder of Realty Quant, a company that brings data-driven and quantitive technologies to the real estate industry. He also holds a master's degree in financial engineering and during his finance career managed a derivative portfolio of over $90B.

Connect with Stefan on LinkedIn and check out his resources on his website https://www.realtyquant.com/

Elisa Zhang is the owner and principal of over $450M in multifamily apartment buildings. She is also a mother of two kids, an artist, an educator, and the breadwinner of her family.

#ezfiuniversity#financial independenece#real estate market#data analysis#Stefan Tsvetkov#financial engineering#portfolio#real estate#economic trends

0 notes

Text

yes obviously the worst part of AYA is all the weird, heteronormative ooc shit but also. I honestly don't think Phineas "laws of physics are despotism" Flynn would willingly go to college

#pnf#phineas and ferb#mine.#like realistically. what the hell would he study. he's doing just fine at 10 without an engineering degree#and if there was a area of study he was interested in i dont think he would spent thousands of dollars#to learn about it in a traditional school setting#my ideal visions of adult! phineas and ferb: college dropouts who are always on the beink of financial disaster#because they hate making money off their inventions

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern day Luffy would be an entomologist. He told his school counselor he wanted to look at bugs for a living and they signed him up for all the science classes. Somehow he’s made his way to being one of the top entomologists in the world

#modern au#one piece#one piece au#Luffy#monkey d luffy#one piece luffy#entomology mentions#somnas.rambles#he likes bugs#somnas.writes#modern day East blue five jobs#Zoro is a personal trainer#Nami is a fashion blogger and a financial advisor#usopp is an engineer#sanji is a professional chef#entomology is the study of bugs btw#I wanna be a forensic entomologist but alas i probably won’t be

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

friendly reminder to BE MAD ABOUT UNITY AND KEEP TALKING ABOUT IT NOTHINGS GOING TO CHANGE IF WE JUST DONT COMMENT ON IT ANYMORE

#unity#unity engine#unity game engine#fuck unity#be mad#rant about this#do something#unity controversy#controversy#stupid fucking big companies ruining lives for financial gain#I hate unity#screw them#the employees are good though their fighting to get it reverted but the executives

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone please pray for my car (and my bank account)... boutta drop at least a grand today on repairs to get her to pass inspection 🫠

#my posts#where's that meme that's like *check engine light comes on* i will never financially recover from this

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The antitrust Twilight Zone

Funeral homes were once dominated by local, family owned businesses. Today, odds are, your neighborhood funeral home is owned by Service Corporation International, which has bought hundreds of funeral homes (keeping the proprietor’s name over the door), jacking up prices and reaping vast profits.

Funeral homes are now one of America’s most predatory, vicious industries, and SCI uses the profits it gouges out of bereaved, reeling families to fuel more acquisitions — 121 more in 2021. SCI gets some economies of scale out of this consolidation, but that’s passed onto shareholders, not consumers. SCI charges 42% more than independent funeral homes.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/09/high-cost-of-dying/#memento-mori

SCI boasts about its pricing power to its investors, how it exploits people’s unwillingness to venture far from home to buy funeral services. If you buy all the funeral homes in a neighborhood, you have near-total control over the market. Despite these obvious problems, none of SCI’s acquisitions face any merger scrutiny, thanks to loopholes in antitrust law.

These loopholes have allowed the entire US productive economy to undergo mass consolidation, flying under regulatory radar. This affects industries as diverse as “hospital beds, magic mushrooms, youth addiction treatment centers, mobile home parks, nursing homes, physicians’ practices, local newspapers, or e-commerce sellers,” but it’s at its worst when it comes to services associated with trauma, where you don’t shop around.

Think of how Envision, a healthcare rollup, used the capital reserves of KKR, its private equity owner, to buy emergency rooms and ambulance services, elevating surprise billing to a grotesque art form. Their depravity knows no bounds: an unconscious, intubated woman with covid was needlessly flown 20 miles to another hospital, generating a $52k bill.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/03/14/unhealthy-finances/#steins-law

This is “the health equivalent of a carjacking,” and rollups spread surprise billing beyond emergency rooms to

anesthesiologists, radiologists, family practice, dermatology and others. In the late 80s, 70% of MDs owned their practices. Today, 70% of docs work for a hospital or corporation.

How the actual fuck did this happen? Rollups take place in “antitrust’s Twilight Zone,” where a perfect storm of regulatory blindspots, demographic factors, macroeconomics, and remorseless cheating by the ultra-wealthy has laid waste to the American economy, torching much of the US’s productive capacity in an orgy of predatory, extractive, enshittifying mergers.

The processes that underpin this transformation aren’t actually very complicated, but they are closely interwoven and can be hard to wrap your head around. “The Roll-Up Economy: The Business of Consolidating Industries with Serial Acquisitions,” a new paper from The American Economic Liberties Project by Denise Hearn, Krista Brown, Taylor Sekhon and Erik Peinert does a superb job of breaking it down:

http://www.economicliberties.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Serial-Acquisitions-Working-Paper-R4-2.pdf

The most obvious problem here is with the MergerScrutiny process, which is when competition regulators must be notified of proposed mergers and must give their approval before they can proceed. Under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) merger scrutiny kicks in for mergers when the purchase price is $101m or more. A company that builds up a monopoly by acquiring hundreds of small businesses need never face merger scrutiny.

The high merger scrutiny threshold means that only a very few mergers are regulated: in 2021, out of 21,994 mergers, only 4,130 (<20%) were reported to the FTC. 2020 saw 16,723 mergers, with only 1.637 (>10%) being reported to the FTC.

Serial acquirers claim that the massive profits they extract by buying up and merging hundreds of businesses are the result of “efficiency” but a closer look at their marketplace conduct shows that most of those profits come from market power. Where efficiences are realized, they benefit shareholders, and are not shared with customers, who face higher prices as competition dwindles.

The serial acquisition bonanza is bad news for supply chains, wages, the small business ecosystem, inequality, and competition itself. Wherever we find concentrated industires, we find these under-the-radar rollups: out of 616 Big Tech acquisitions from 2010 to 2019, 94 (15%) of them came in for merger scrutiny.

The report’s authors quote FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter: “I think of serial acquisitions as a Pac-Man strategy. Each individual merger viewed independently may not seem to have significant impact. But the collective impact of hundreds of smaller acquisitions, can lead to a monopolistic behavior.”

It’s not just the FTC that recognizes the risks from rollups. Jonathan Kanter, the DoJ’s top antitrust enforcer has raised alarms about private equity strategies that are “designed to hollow out or roll-up an industry and essentially cash out. That business model is often very much at odds with the law and very much at odds with the competition we’re trying to protect.”

The DoJ’s interest is important. As with so many antitrust failures, the problem isn’t in the law, but in its enforcement. Section 7 of the Clayton Act prohibits serial acquisitions under its “incipient monopolization” standard. Acquisitions are banned “where the effect of such acquisition may be to substantially lessen competition between the corporation whose stock is so acquired and the corporation making the acquisition.” This incipiency standard was strengthened by the 1950 Celler-Kefauver Amendment.

The lawmakers who passed both acts were clear about their legislative intention — to block this kind of stealth monopoly formation. For decades, that’s how the law was enforced. For example, in 1966, the DoJ blocked Von’s from acquiring another grocer because the resulting merger would give Von’s 7.5% of the regional market. While Von’s is cited by pro-monopoly extremists as an example of how the old antitrust system was broken and petty, the DoJ’s logic was impeccable and sorely missed today: they were trying to prevent a rollup of the sort that plagues our modern economy.

As the Supremes wrote in 1963: “A fundamental purpose of [stronger incipiency standards was] to arrest the trend toward concentration, the tendency of monopoly, before the consumer’s alternatives disappeared through merger, and that purpose would be ill-served if the law stayed its hand until 10, or 20, or 30 [more firms were absorbed].”

But even though the incipiency standard remains on the books, its enforcement dwindled away to nothing, starting in the Reagan era, thanks to the Chicago School’s influence. The neoliberal economists of Chicago, led by the Nixonite criminal Robert Bork, counseled that most monopolies were “efficient” and the inefficient ones would self-correct when new businesses challenged them, and demanded a halt to antitrust enforcement.

In 1982, the DoJ’s merger guidelines were gutted, made toothless through the addition of a “safe harbor” rule. So long as a merger stayed below a certain threshold of market concentration, the DoJ promised not to look into it. In 2000, Clinton signed an amendment to the HSR Act that exempted transactions below $50m. In 2010, Obama’s DoJ expanded the safe harbor to exclude “[mergers that] are unlikely to have adverse competitive effects and ordinarily require no further analysis.”

These constitute a “blank check” for serial acquirers. Any investor who found a profitable strategy for serial acquisition could now operate with impunity, free from government interference, no matter how devastating these acquisitions were to the real economy.

Unfortunately for us, serial acquisitions are profitable. As an EY study put it: “the more acquisitive the company… the greater the value created…there is a strong pattern of shareholder value growth, correlating with frequent acquisitions.” Where does this value come from? “Efficiencies” are part of the story, but it’s a sideshow. The real action is in the power that consolidation gives over workers, suppliers and customers, as well as vast, irresistable gains from financial engineering.

In all, the authors identify five ways that rollups enrich investors:

I. low-risk expansion;

II. efficiencies of scale;

III. pricing power;

IV. buyer power;

V. valuation arbitrage.

The efficiency gains that rolled up firms enjoy often come at the expense of workers — these companies shed jobs and depress wages, and the savings aren’t passed on to customers, but rather returned to the business, which reinvests it in gobbling up more companies, firing more workers, and slashing survivors’ wages. Anything left over is passed on to the investors.

Consolidated sectors are hotbeds of fraud: take Heartland, which has rolled up small dental practices across America. Heartland promised dentists that it would free them from the drudgery of billing and administration but instead embarked on a campaign of phony Medicare billing, wage theft, and forcing unnecessary, painful procedures on children.

Heartland is no anomaly: dental rollups have actually killed children by subjecting them to multiple, unnecessary root-canals. These predatory businesses rely on Medicaid paying for these procedures, meaning that it’s only the poorest children who face these abuses:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/17/the-doctor-will-fleece-you-now/#pe-in-full-effect

A consolidated sector has lots of ways to rip off the public: they can “directly raise prices, bundle different products or services together, or attach new fees to existing products.” The epidemic of junk fees can be traced to consolidation.

Consolidators aren’t shy about this, either. The pitch-decks they send to investors and board members openly brag about “pricing power, gained through acquisitions and high switching costs, as a key strategy.”

Unsurprisingly, investors love consolidators. Not only can they gouge customers and cheat workers, but they also enjoy an incredible, obscure benefit in the form of “valuation arbitrage.”

When a business goes up for sale, its valuation (price) is calculated by multiplying its annual cashflow. For small businesses, the usual multiplier is 3–5x. For large businesses, it’s 10–20x or more. That means that the mere act of merging a small business with a large business can increase its valuation sevenfold or more!

Let’s break that down. A dental practice that grosses $1m/year is generally sold for $3–5m. But if Heartland buys the practice and merges it with its chain of baby-torturing, Medicaid-defrauding dental practices, the chain’s valuation goes up by $10–20m. That higher valuation means that Heartland can borrow more money at more favorable rates, and it means that when it flips the husks of these dental practices, it expects a 700% return.

This is why your local veterinarian has been enshittified. “A typical vet practice sells for 5–8x cashflow…American Veterinary Group [is] valued at as much as 21x cashflow…When a large consolidator buys a $1M cashflow clinic, it may cost them as little as $5M, while increasing the value of the consolidator by $21M. This has created a goldrush for veterinary consolidators.”

This free money for large consolidators means that even when there are better buyers — investors who want to maintain the quality and service the business offers — they can’t outbid the consolidators. The consolidators, expecting a 700% profit triggered by the mere act of changing the business’s ownership papers, can always afford to pay more than someone who merely wants to provide a good business at a fair price to their community.

To make this worse, an unprecedented number of small businesses are all up for sale at once. Half of US businesses are owned by Boomers who are ready to retire and exhausted by two major financial crises within a decade. 60% of Boomer-owned businesses — 2.9m businesses of 11 or so employees each, employing 32m people in all — are expected to sell in the coming decade.

If nothing changes, these businesses are likely to end up in the hands of consolidators. Since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, private equity firms and other looters have been awash in free money, courtesy of the Federal Reserve and Congress, who chose to bail out irresponsible and deceptive lenders, not the borrowers they preyed upon.

A decade of zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) helped PE grow to “staggering” size. Over that period, America’s 2,000 private equity firms raised buyout warchests totaling $2t. Today, private equity owned companies outnumber publicly traded firms by more than two to one.

Private equity is patient zero in the serial acquisition epidemic. The list of private equity rollup plays includes “comedy clubs, ad agencies, water bottles, local newspapers, and healthcare providers like hospitals, ERs, and nursing homes.”

Meanwhile, ZIRP left the nation’s pension funds desperate for returns on their investments, and these funds handed $480b to the private equity sector. If you have a pension, your retirement is being funded by investments that are destroying your industry, raising your rent, and turning the nursing home you’re doomed to into a charnel house.

The good news is that enforcers like Kanter have called time on the longstanding, bipartisan failure to use antitrust laws to block consolidation. Kanter told the NY Bar Association: “We have an obligation to enforce the antitrust laws as written by Congress, and we will challenge any merger where the effect ‘may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.’”

The FTC and the DOJ already have many tools they can use to end this epidemic.

They can revive the incipiency standard from Sec 7 of the Clayton Act, which bans mergers where “the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.”

This allows regulators to “consider a broad range of price and non-price effects relevant to serial acquisitions, including the long-term business strategy of the acquirer, the current trend or prevalence of concentration or acquisitions in the industry, and the investment structure of the transactions”;

The FTC and DOJ can strengthen this by revising their merger guidelines to “incorporate a new section for industries or markets where there is a trend towards concentration.” They can get rid of Reagan’s 1982 safe harbor, and tear up the blank check for merger approval;

The FTC could institute a policy of immediately publishing merger filings, “the moment they are filed.”

Beyond this, the authors identify some key areas for legislative reform:

Exempt the FTC from the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) of 1995, which currently blocks the FTC from requesting documents from “10 or more people” when it investigates a merger;

Subject any company “making more than 6 acquisitions per year valued at $70 million total or more” to “extra scrutiny under revised merger guidelines, regardless of the total size of the firm or the individual acquisitions”;

Treat all the companies owned by a PE fund as having the same owner, rather than allowing the fiction that a holding company is the owner of a business;

Force businesses seeking merger approval to provide “any investment materials, such as Private Placement Memorandums, Management or Lender Presentations, or any documents prepared for the purposes of soliciting investment. Such documents often plainly describe the anticompetitive roll-up or consolidation strategy of the acquiring firm”;

Also force them to provide “loan documentation to understand the acquisition plans of a company and its financing strategy;”

When companies are found to have violated antitrust, ban them from acquiring any other company for 3–5 years, and/or force them to get FTC pre-approval for all future acquisitions;

Reinvigorate enforcement of rules requiring that some categories of business (especially healthcare) be owned by licensed professionals;

Lower the threshold for notification of mergers;

Add a new notification requirement based on the number of transactions;

Fed agencies should automatically share merger documents with state attorneys general;

Extend civil and criminal antitrust penalties to “investment bankers, attorneys, consultants who usher through anticompetitive mergers.”

#pluralistic#american economic liberties project#jonathan kantor#doj#clayton act#hart-scott-rodino act#zirp#financial engineering#monopoly#consolidation#rollups#debt financing#private equity#hedge funds#serial acquirers#antitrust#incipiency standard#Celler-Kefauver Act#vons#brown shoe#boomers#silver wave#labor#monopsony#pricing power#kkr#envision#funeral homes#surprise billing#sci

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm a reasonable guy, I just think that the current state of italian websites should be condemned by the UN or something

#i just think that if you need to navigate a website in order to get financial help/a job/healthcare/etc#and that website looks like it hasn't been updated in 10 years and requires a diploma in engineering to use#i just think that should be criminalised

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i do think that incuriosity is a death knell for someone becoming an interesting, well-rounded, and worth-talking-to person, but the major you specialize in in undergrad- and indeed whether you go to undergrad at all- has jack shit to do with this.

#the most interesting people i talk to range from people who could not finish college due to financial issues#to people with undergrads in literature to people with PhDs in biosystems engineering#and beyond...

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Learn more about interesting data analysis Stefan has done during past historical events and how it can help you think differently about what is going on in the economy today.

Stefan is the Founder of Realty Quant, a company that brings data-driven and quantitive technologies to the real estate industry. He also holds a master's degree in financial engineering and during his finance career managed a derivative portfolio of over $90B.

Connect with Stefan on LinkedIn and check out his resources on his website https://www.realtyquant.com/

#ezfiuniversity#financial independenece#real estate market#data analysis#Stefan Tsvetkov#real estate industry#financial engineering#real estate portfolio#economic trends

0 notes

Note

I FUCKING GOT IN SOMEHOW LETS GOOOO BROWN ENGINEERING 2028 NOW I NEED TO FIGURE OUT FINANCIAL AID

Congratulations haha!! It's very exciting :) A few admins have experience with being engineering TAs here so if you have any questions about that plz ask, also about financial aid

I know Brown didn't offer me as much aid as other schools when I got in, but then I showed them how much aid another school gave me and I got around $10k more from Brown! I'm guessing you're an early decision applicant so I don't know that this applies, but the moral is you can contest the award they give you and potentially get more money

2 notes

·

View notes