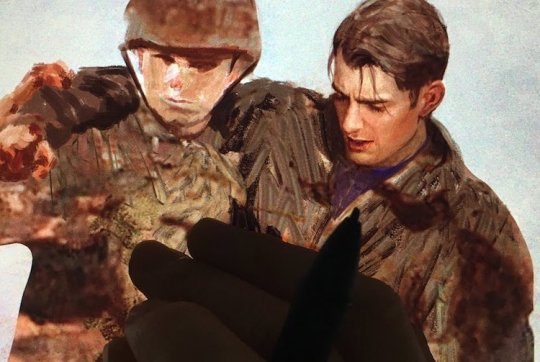

#eternally chasing after the perfect paint texture

Photo

a WIP

#haven't posted one here in a long time#wip#m draws#eternally chasing after the perfect paint texture

435 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forever falling: Vertigo

For some, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) has always been one of those ‘bedside’ films (as François Truffaut put it, before such a thing could be taken literally) – which means that we store it so well in our minds, and in our hearts, that we can think about it and ‘watch’ it again whenever the mood takes us. We do this to delve a little bit deeper into the film’s inexhaustible and fascinating enigmas, to relive our first impressions and to compare Hitchcock’s film to the rest of filmmaking – if only to reassure ourselves of its status as an unsurpassed peak, making films that hold more prestige for critics and historians seem lesser works by comparison. And yet the truth is that its status as a great work has only been admitted comparatively recently.

None of Hitchcock’s films, for instance, featured in Sight & Sound’s first top ten in 1952, and Vertigo didn’t feature in the 1962 critics’ poll, compiled four years after the film’s release. In fact Vertigo didn’t appear in the poll until 1982, when it came seventh. By 1992 it was up to fourth (and sixth in the newly instigated directors’ poll); then in 2002 it came second (remaining sixth for the directors).

Why did it take so long? Unlike, say, Bicycle Thieves, which was more or less instantly acclaimed as a masterpiece (coming top in the 1952 poll, only four years after its release), films such as Vertigo and John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) initially met with a mixed reception from critics – and with indifference from the public. Which means that, beyond the mere passing of time and the perseverance of their defenders, these works must have something very special about them to have been able to finally impose themselves as great works.

But why, in the case of Vertigo, do we come back again and again, even though the art of cinema and the film’s original audience have changed? The generation that first revered the film has got older and gained experience, but we have also lost illusions and enthusiasm. Why, after watching Vertigo more than, say, 30 times, are we confident that there are things to discover in it – that some aspects remain ambiguous and uncertain, unfathomably complex, even if we scrutinise every look, every cut, every movement of the camera? Why do we never get tired of Hitchcock telling us the story of Scottie Ferguson’s obsession with three people in one – Madeleine Elster, Carlotta Valdes and Judy Barton – even though we know it by heart?

Narrative discoveries

It is generally accepted that Hitchcock was one of the great film narrators. He has long been considered a skilful artisan at the service of his audience, willing to flatter us, and eager to make the biggest profit with his products – a direct concern for him, because he participated in the financing of his films, which meant that his future creative freedom depended on good commercial results. Hitchcock always wanted to keep his hands free so he could make something greater than he’d made before.

The tendency among earlier critics was to try to reduce him to the role of ‘master of suspense’, perhaps because his success sparked off a multitude of inferior imitators. Hitchcock’s narrative discoveries, the structural audacity with which he surprised us – the death of the love interest 70 minutes into Vertigo, or of protagonist Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) 40 minutes into Psycho – all those innovations were considered mistakes by critics then. These were possibilities no other producer would have tolerated; even with Hitchcock’s creative autonomy, few would have dared to attempt them.

Of course Hitchcock understood the importance of dramatic narrative and character conventions. He knew how to play with them and pretend he was complying with them – as when retired policeman Scottie (James Stewart) initiates his investigation of Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) at the behest of her husband Gavin (Tom Helmore) – so that the spectator, trusting in orthodoxy, would anticipate the position where the director wanted them to be, allowing him to create and dilate that mixture of tension and uncertainty that is ‘suspense’.

Come the time, he also knew how to brutally undermine those conventional expectations (making us realise, for instance, that Scottie has been suckered into the Elster case because of his fatal flaw, the vertigo he has experienced ever since he was left dangling from the edge of a roof during a chase in the film’s opening sequence), leaving the spectator disoriented – and therefore ready to be taken wherever he wanted us to go.

Hitchcock knew that an excess of confusion can distance, that too many explanations can tire and make us lose the thread, that a prolonged vagueness can jeopardise the credibility of a story. Yet he also knew that if one wants to put aside (or forget for a while) the plausible and go deep into the terrain of the extraordinary and the improbable, ambiguity is necessary to preserve a fragile realism – in misè en scene, wardrobe, behaviour. Hitchcock was never spineless in this regard: when he was certain, he would jump in and violate any rule.

This allowed him to dive into the depths of the invisible, the ungraspable, the imperceptible, the unsafe, the weightless, the strange, the impossible (that which worryingly can happen). And this would provide him with the most adequate and efficient tools to lure us into that “momentary suspension of disbelief” of which Coleridge spoke, and elongate it in order for us to immerse ourselves in the inextricable depths of the human being. I won’t use the word ‘soul’, even though I’m sure Hitchcock believed in the existence of something like this.

There is no need to be a Christian to succumb to Hitchcock, just – ever so slightly – Freudian or Jungian. I suspect that Hitchcock, regardless of how sceptically or ironically he considered the jargon of psychoanalysis and its therapeutic virtues, didn’t ignore the theories and the institutions of the different psychoanalytic schools. Subjects that preoccupied and intrigued Sigmund Freud and his followers – such as sexuality and repression, dreams and the Oedipus complex, fear and the ‘lapsus’, lies and masks, sublimation and mythology, jokes, the subconscious and feelings of guilt, the illusion of grandeur and the persecution complex, paternal or authoritarian figures and possessive mothers, the family structure and hereditary features, child fixations and hysteria, hypnotism and schizophrenia, the uncanny and many others – seem like a repertoire of themes that recur in Hitchcock’s filmography.

That said, Catholicism provided Hitchcock with certain variations (or aggravating circumstances) on some of these themes: the notion of sin; the fear of knowledge and of woman as dangerous temptress; the expulsion from Paradise and the shame of the body; the mythologising of virginity and maternity; plagues and the way to the cross; mourning and the cult of the dead; faith in the afterlife and in the resurrection of the flesh; the Ten Commandments and the Seven Deadly Sins as opportunities for transgression and guilt; miracle healing; eternal punishment; the consecration of ‘the wrong man’ in the figure of Christ; confession and its inviolable confidentiality; the inquisition and torture; the devil as seductive and astute being, proudly defiant of the divine supremacy; the conflict between predestination and freedom; the Apocalypse and the Last Judgement…

It would be as ridiculous to deny the importance of Judaeo-Christian obsessions in Hitchcock as it would be to reduce everything to a succession of Catholic dogmas and rituals. These obsessions are the perfect complement, conflictual and partly antithetical – and therefore dialectical, to his psychoanalytic sources of inspiration.

Another even less explored cultural source for Hitchcock – which strengthens the Catholic (which came from his education by the Jesuits) and the Freudian (which he encountered during his film apprenticeship in Weimar-era Germany) – is surrealism. This may be obvious, but in order to highlight it we need to look at the composition and framing, the texture and the combination of his images – above all in the silent part of his British period, chronologically the closest to those encounters.

Like the surrealists, Hitchcock thought that the interior (what happens ‘inside’) and the imaginary (dreamed, remembered or hallucinated) are as real as the external and tangible to which ‘reality’ is normally restricted. The influence here is not primarily literary but rather pictorial, and can be sensed in paintings by Richard Oelze, Max Ernst, Emil Nolde, Dorothea Tanning, Hans Bellmer, and in some of their predecessors, such as Friedrich, Böcklin, Munch and Fuseli.

Lastly, there remains a vision of the world to which this last clue drives us: romanticism. From many spheres – musical, literary, pictorial – and from various places – British, German, Italian, American, Russian – the footprints of romanticism can be detected in Hitchcock’s films. One feels the spectres of Poe, Stevenson, Hawthorne, Melville, George Du Maurier, Emily and Charlotte Brontë, Mary Shelley, Wilkie Collins, Georg Trakl, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Achim von Arnim and Gérard de Nerval.

In the same way, one can hear – under the curiously related melodies composed for his films by such different musicians as Franz Waxman, Hugo Friedhofer, Roy Webb, Maurice Jarre, Miklós Rózsa, Dimitri Tiomkin and above all Bernard Herrmann – measures and harmonies by Wagner, Brahms, Schubert, Schumann, Richard Strauss, Fauré, Franck, Rachmaninov, Debussy, Britten, early Stravinsky, the Schoenberg of ‘Verklärte Nacht’ (‘Transfigured Night’) – all of them centred in the recreation and transmission of emotions.

For me romanticism – often concealed under a layer of cynicism and humour, as in Lubitsch, Sternberg, Wilder, Ophuls, Stroheim or Mankiewicz – is the key to Hitchcock’s unequalled capacity to unsettle and move the spectator with a degree of implication and intensity that goes beyond a supposed ‘identification’ with the protagonist – an identification that Hitchcock tended to rupture violently and traumatically, and which in general was projected not on to a single (male) person, but on to the couple, at least.

Notorious (1946), for instance, is not the story of Devlin (Cary Grant) – even if its first part is told from his narrative (but not visual) point of view – nor is it that of Alicia (Ingrid Bergman), as the title may make us think; it is the story of that couple – or more so, of the triangle composed by Sebastian (Claude Rains), and the quadrilateral that would include his ominous mother (Leopoldine Konstantin).

More than the drama of the neurotic woman personified by Tippi Hedren, Marnie (1964) narrates her complex relationship with Mark Rutland (Sean Connery), and the no less ambiguous relationship with her mother. Vertigo, of course, is not just the story of Scottie, but also – even more so – of Judy in her different simulations or incarnations, manipulated, feigned, spontaneous or forced.

Seduction manoeuvres

Another reason why Vertigo turns out to be so intriguing, complex and suggestive stems from the fact that it gathers together a strange synthesis of various myths of Western culture, connected to the mystery of artistic creation, which is perhaps the film’s ultimate subject.

The most obvious myth is Pygmalion, combined with the Frankenstein variant of Prometheus; others would include Orpheus and Eurydice, although in a very sombre version, and almost inverted; the double or Döppelganger of the romantics and German expressionists, filtered through the schizoid sieve of Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; the love in death and beyond this world of ‘Tristan and Isolde’ (and it is no coincidence that the ‘Liebestod’ of Wagner’s opera is the audible origin of Herrmann’s score, mainly of the ‘Love Theme’); some vampire tales and the novel Peter Ibbetson by George Du Maurier (not the pale and miscast film version by Henry Hathaway).

Some others could also be mentioned, such as Faust, but what’s interesting here is that it is not a case of showing off cultural references, but of a melancholic and tragic story of love (much more than a detective story), full of multiple resonances that are admirably integrated, and which converge in what Robin Wood, Jean Douchet and Eugenio Trías have considered a parable of creation, and of the mise en scène.

Let’s not forget that Vertigo is a succession of mises en scène and seduction manoeuvres. The first shows us how Gavin Elster, an old friend from student days, requests Scottie’s services as a detective in order to use him in an improbable criminal conspiracy. First he tempts him, like Mephistopheles, with a return to action, restoring Scottie’s lost confidence. Once this route fails, Elster intrigues him with the implausible story of Carlotta Valdes and the power it exerts over his wife Madeleine – a story told in encircling movements, going up and down the different ‘levels’ of his huge office, like the scriptwriter and director who first seduce the producer, then the actors and finally the audience. Elster banks on the fact that – in a third phase, admirably staged in Ernie’s restaurant – Scottie is going to be captivated by the ethereal, ghostly, hieratic and gliding beauty of Madeleine, which will finally convince him to believe such a fantastic tale and accept the mission of following and protecting her.

From the moment he positions himself inside his car at the door of Elster’s mansion and furtively follows Madeleine, Scottie thinks he is directing the second mise en scène. The mix of contemplation and distance and growing curiosity is intoxicating as Scottie, without realising it, starts falling in love with an imaginary person whom he dreams of saving, without ever suspecting that ‘Madeleine’ has been forced to interpret a role. He follows her, bewitched, through different places, each more or less funereal: a flower shop, which she enters through the back door; the cemetery of the Mission Dolores; the museum where she contemplates the portrait of the unfortunate Carlotta; the lonely room in the sinister and desolate McKittrick Hotel (a herald of the house in which Norman Bates coexists with the memory of his mother), in which Madeleine vanishes like a ghost, as if she were a hallucination of Scottie’s.

His unconscious desires start to become a reality when Madeleine throws herself into San Francisco Bay by the Golden Gate, giving him the opportunity to save her like some knight errant – and to feel, as in the Chinese tradition he cites, responsible for her; to take her to his flat, undress her, watch her sleeping and talk to her for the first time. In this phase, a relationship of affinity binds these prowling idlers. They visit different places on the outskirts of San Francisco, exchange confidences, fears and dreams. This phase is consummated – once Scottie is in love with Madeleine – with the unseen murder of Elster’s real wife, presented traumatically to Scottie (and the viewer) as a suicide that he couldn’t prevent.

The third mise en scène takes to the limit the condition of the powerless spectator, which we share with Scottie; it’s a painful repetition, under the effects of the loss or abandonment syndrome of the previous ‘movement’. Like an inconsolable widower, Scottie revisits the places where he first followed and spied on Madeleine from a distance, and those where they were together: the giant sequoias, the solitary coast beaten by the swell and the wind, the Mission San Juan Bautista.

The fourth mise en scène – after a few false alarms that leave us breathless, making our heart skip in rhythm with the wounded and depressed Scottie – starts when the ex-detective bumps into Judy Barton. A shop assistant, she seems carnal, even vulgar – very far from the formal elegance and distinction of Madeleine, who was so pale and whispering, so shy and fragile, so ethereal and disturbed; but in Judy he discovers an echo of the loved and lost image. Now Scottie becomes scriptwriter and producer, director and wardrobe designer, make-up artist and decorator, as he obsessively tries to transform Judy into his Madeleine, taking that resemblance as a starting point, polishing and fine-tuning her into the yearned-for image of his unacceptably lost love.

But Judy is scared, because she knows what Scottie and we still don’t. The key moment of the film – truly revolutionary from the dramatic and narrative point of view – is the revelation (for us the spectators, when we hear Judy writing her confession; Scottie’s realisation will still take a bit longer) of what really happened on the top of the bell tower of the Mission. This is a moment that gives a different sense to everything we think we know, and changes our point of view: we shift from Scottie’s viewpoint – from the sadness and desperation we’ve shared – to Judy’s, which allows us to consider her as a victim.

The fifth mise en scène begins when Judy, trapped by the love she had to feign for Scottie when she was experiencing his so intensely, gives herself away – almost abandons herself to love – with an indirect confession. (It’s difficult to know to what extent it’s conscious on Judy’s part; is she even jealous of the fictitious Madeleine, who was herself?)

When Scottie tries to regain control of the drama – which will now be that of vengeance, as he is determined to force a confession out of Judy – he will drag her to her death. And this is the definitive disappearance of Madeleine that will drive Scottie to the absolute void. In the end, Scottie is left ‘suspended’ over the abyss, just as he was when a compassionate fade-out closed the film’s prologue of the police chase over the roofs of San Francisco.

During this gradual process of spiral ascents and falls, punctuated by ominous low and high angles, we the viewers are successively – or simultaneously – busybodies and onlookers, meddlers and dupes, accomplices and sceptics, co-scriptwriters and extras, witnesses and victims of three machinations: Elster’s, Scottie’s and – above both of them, permanent and masterly – Hitchcock’s.

Miguel Marías

Sight & Sound 2012 poll essay

https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/greatest-films-all-time/forever-falling-vertigo

0 notes

Text

Assignment代写:The theme of love in Renaissance poetry

下面为大家整理一篇优秀的assignment代写范文- The theme of love in Renaissance poetry,供大家参考学习,这篇论文讨论了文艺复兴时期诗歌中关于的爱情主题。文艺复兴运动,将人们的情感从中世纪的宗教桎梏中解放出来,而爱情作为感情的强烈表现,也在文艺复兴时期的文艺作品中得到了尽情的展现。在众多的爱情诗中,爱情的主题也各有侧重,或谈情,或言性。在诗人的笔下,爱情呈现着不同的姿态。每一个诗人,每一首诗,都言及一面,共同描绘出了一个绚烂无比的爱情的宏大主题。

The Renaissance liberated people's feelings from the shackles of religion in the century. Love, as a strong expression of feelings, was also fully displayed in the Renaissance works. In many love poems, the theme of love also has different focuses, or talk about love, or speech. This paper chooses three different love poems of different poets in this period. By comparing the similarities and differences of the images in the poems, it reveals the diversified love views and different ways of expressing love in this period.

As a movement, the Renaissance, after a century, swept across Europe, swept away the clouds and shackles of the medieval "dark age", and let the light of human nature shine again in all aspects of human life. The ancient and unchanging love also sheds a new light in the human nature. In this period, each kind of art is extolling love in its own way. The sweetness, sanctity, variety and diversity of love are especially favored by poets. In their writing, love takes on a different posture, or fragrance, or tenderness, or passion of temptation, or sanctity. Every poet, every poem, all speak one side, and together they depict a grand theme of gorgeous love. The author selected three love poems of the three poets in this period, hoping to get a glimpse of the unique expression of love theme in Renaissance poetry.

When it comes to love, whether exquisite or sublime, we often think of the passionate feelings between lovers or the lovey-dovey couple world. However in edmond spencer's "one day, I wrote her name in the sand," a poem, people realize in the romantic poetry is bold and unrestrained feelings, or already familiar with the heroic action in the ancient Greek drama has disappeared. The heroine and the "I" is more like two metaphysician rather than lovers, is talking about the xuan talk rather than on love affairs, call each other also let a person feel no enthusiasm, in the poem of appellation is not about sight that specific vivid image, the lovers and often about such as "immortal", such as "good" and "virtue" abstract concepts. Though your name is full of "light" in the poet's heart, it is only "written in heaven". The heroine's exclamation to the hero is just a "conceited person", which does not sound half passionate, but is just an objective and calm criticism. There is not a word of love in the poem that relates to these two, but to "my poem" and to eternity: "my poem perpetuates your rare virtue." The "I" in the poem is more like a knight in the middle ages, only the sword in the hand turns into a sonnet to win the "good name" and "brilliance" for the heroine whose appearance is hidden in the poem. And the knight for all her action is no longer a battle sword, but the reduction of a monotonous move: "write her name in the sand", this behavior is not in contact with her, and leave no trace, because "the waves to the" will "wash away the name", this kind of behavior is more like a meditator, rather than the love between lovers will happen, but now that the names have been wiped out the waves and that will not assume any responsibility, then this behavior will not cause any results. Accordingly, a whole "she" image has been reduced to a mere name. Even if this "good name" could be made immortal, there would be nothing left but an empty symbol. Though this is a love poem, it loses its sweetness. It seems that once love is distilled, all emotions vanish into clouds.

Christopher Marlowe's "shepherd's song", the opening with a warm imperative sentence invites readers to share in love the enthusiasm of the shepherd: "come on, and I live together, be my love." The abstract pursuit in Spenser's poem becomes the earnest call, the fame and glory become the secular life. Most of the actions in the poem are directly related to the two lovers who are in love with each other. Otherwise, they also express the shepherd's strong determination to pursue and his sincere praise for the lover being pursued. In stanzas or stanzas, the plural subject "we" triggers a series of actions. On the one hand, the modal verb "will" promises his lover a beautiful and bright future, on the other hand, it shows his strong desire to achieve such a future. From the beginning of verse 3, a series of actions led by "I will" reveal the shepherd's will and determination. Whether the "I" in the poem is "a bed made of thousands of bouquets of flowers" or "a belt made of ivy and aromatic grass", it is to "move" and "your heart". Readers will be surprised by the many concrete images in the poem, such as "valley countryside", "lamb", "bird", "rose", "gown", and so on, compared with the abstract concept of "good name" or "virtue" in spencer's poem, all of which are not in the concrete and vivid life. All these concrete images together paint a vivid picture of personal life. At this point, we should notice that the images of nature in the two poems are different. In Spenser's poem, the image of nature exists only as a pure background. As soon as the subject is lit, it will be invisible again in the dark. In marlow's poem, nature is light itself. "Come and live with me" is to live in the "beautiful valley of the lambs". Besides the eagerness, initiative and directness of the shepherd, the image of the heroine in the poem is also embodied to some extent. From verse 3 to verse 6, the image of a girl who is dressed up to be loved, entertained with all her heart, and loved, appears vividly in the eager discourse of the shepherd. However, this beloved girl is still invisible in many images, only in this rich rhetoric of existence.

Spencer girl didn't play in the poem, Marlowe girl in poem in a figurative sense only to the presence of John donne "bait", seems to describe a complete woman. From verse 2, the poem celebrates not only her glowing "eyes," but also her actions: "swimming in that flowing bath." The image of a woman is no longer an abstract name, not a fancy dress, but a flesh-and-blood woman who can act. In poetry, women's behavior is condensed into a tantalizing bait in the phrase "you are your own bait." This echoes an image at the end of the first stanza: the hook. "Silver hook" brings the reader a sense of cold, sharp, ruthless and cunning, as well as a desire to conquer and initiative. The image along with other image at the beginning of the poem, such as "cold water", "slippery line", the sense that gives a person is far from comfortable, but annoying and disturbing, this poetry and poetry parodying Marlowe open sentence "come on, and I live together, be my love, / us fresh happiness is endless" give a person look forward to in different ways. It wasn't long before this uneasy feeling became a whole cruel picture of love. Others who try to win love must "freeze in the reed," "cut their legs," or use "broken nets," or use "flies" as bait, while the woman in the poem "needs no such trick" to win love easily because she is "her own bait." Though still the object of the chase, she was distinguished for her beauty, and could seduce men without the need for them to seduce her with eternal or perfect life. It is also almost impossible to find a suitor as clearly as it is in spencer's or marlow's poem, in which only the image of a group of pleasure-seekers emerges in the form of a shoal of fish. Trapped by the bait, the fish from every river "happily went to catch" her. The love in the poem is more like a game, full of temptation, trick and catch - release process. "Bait" this image is not only exists in the metaphor, but everywhere retained actually layer surface texture, such as "hooks" and "amorous" and "catch" word, contains a strong meaning of sex. Compared with the abstract concepts of spencer's poetry or marlow's pastoral life, the bait is more detailed, direct and specific, but once hooked, the cruelty, coldness and ruthlessness of love are as specific as physical pain and bloodshed.

Although the three poems are love poems, they are different from each other. Spencer's abstract ideal of love may be longer than marlow's idyllic life, but there is no sense of truth to it. Similarly true and concrete, donne's sexual love, which is full of seduction, is stronger, but it is also colored with pain by its intensity, losing the purity of spencer's poem and the sincerity of marlow's. But it is difficult to discern clear linear development in the three poems. If dorn and marlow's poems are more concrete than spencer's, this abstraction may be just spencer's personal style. The same theme is much more vivid in Shakespeare's 18 sonnets. The insignificance of nature in Spenser became the key in marlow's poetry, and this love of nature failed to continue; In donne's poems, the once-sweet images of nature became rough "reed marshes," "shells and weeds." The female image seems to be strengthened and gradually clarified in the three poems. But passionately in love shepherd also did not describe the image of the lover eagerly, the specific decorations, utensils covered the specific female image. Marlow's shepherds and spencer's meditators are not that different. They are in control of their love and not paying attention to their lovers. Only the women portrayed by donne caught the "thread and hook" and took the lead. However, the women in donne's poems were only endowed with sexual attraction rather than the power of love, so donne failed to establish the image of a woman in love.

Although simplicity is dangerous and harmful, it does not hurt to say that love is expressed in its pluralism and pluralism. The three poems above prove this truth. Love glows eternal in spencer's poems, a warm pulse beats in marlow's poems, and in donne's works, sensuous enjoyment and temptation becomes another melody of love. It is this variety that keeps love alive, and it is love that is loved by poets. The diversified expression and the diversified presentation jointly depict the beautiful image of love, which is unique in the long middle ages. Meanwhile, it also opens up space for poets in later generations to express love with stronger feelings and bolder words.

51due留学教育原创版权郑重声明:原创assignment代写范文源自编辑创作,未经官方许可,网站谢绝转载。对于侵权行为,未经同意的情况下,51Due有权追究法律责任。主要业务有assignment代写、essay代写、paper代写服务。

51due为留学生提供最好的assignment代写服务,亲们可以进入主页了解和获取更多assignment代写范文 提供美国作业代写服务,详情可以咨询我们的客服QQ:800020041。

0 notes