#dominique francon

Text

lana del rey music really is so dominique francon

#red lipstic#blue jeans#collared white shirt#short 20s hair#depression#lana del rey#dominique francon#the fountainhead#by Ayn Rand#ayn rand books#howard roark

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

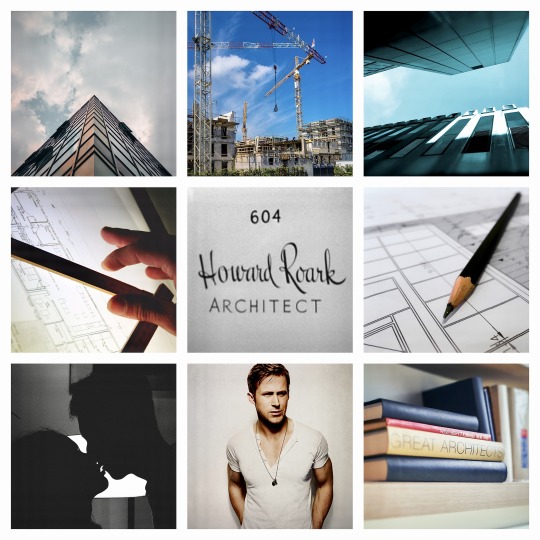

Photo

Gary Cooper in The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949)

Cast: Gary Cooper, Patricia Neal, Raymond Massey, Robert Douglas, Kent Smith, Henry Hull, Ray Collins. Screenplay: Ayn Rand, based on her novel. Cinematography: Robert Burks. Art direction: Edward Carrere. Music: Max Steiner.

Ayn Rand, proponent of a "philosophy" beloved of 20-year-old frat-boy business majors, is still very much with us, as the would-be Randian Übermensch who recently inhabited the White House too well demonstrates. So it's probably worth brushing up on the ideas that seem to captivate perpetual adolescents and sociopaths. Fortunately, you don't have to slog through her doorstop novels to get the gist: All you have to do is watch The Fountainhead, for which she wrote the screenplay. Its sociopath hero, Howard Roark, would be intolerable if he weren't played by Gary Cooper, taking on a role that is a curious inversion of the "common man" he played for Frank Capra in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) or the pawn of the Establishment in Meet John Doe (1941). Cooper's occasional eye twinkles or wry smiles help keep us from believing that he's really the kind of arrogant shit who says things like "I don't give or ask for help" or "The world is perishing from an orgy of self-sacrificing." As Dominique Francon, Patricia Neal does a lot of seething and surging about; it's not a good performance by a long shot, but it's watchable. But Raymond Massey manages to give an almost good performance, even when forced to deliver lines like: "What I want to find in our marriage will remain my own concern. I exact no promises and impose no obligations. Incidentally, since it is of no importance to you, I love you." Was ever woman in this humor wooed? The real saving grace of The Fountainhead, however, is its director, King Vidor, whose career began and flourished in the silent era, with classics like The Big Parade (1925) and The Crowd (1928), which honed his visual sense before he had to work with dialogue. If The Fountainhead had been a silent movie, not cluttered with Rand's dialogue and sermonizing, it might have been a classic itself, especially since it had a first-rate cinematographer in Robert Burks and a clever set designer in Edward Carrere. Max Steiner's overbearing score also helps distract us from the clanking and clattering of Rand's screenplay. The Fountainhead, in short, is a hoot, but a perversely fascinating one.

0 notes

Text

The Fountainhead - Ayn Rand

EPUB & PDF Ebook The Fountainhead | EBOOK ONLINE DOWNLOAD

by Ayn Rand.

Download Link : DOWNLOAD The Fountainhead

Read More : READ The Fountainhead

Ebook PDF The Fountainhead | EBOOK ONLINE DOWNLOAD

Hello Book lovers, If you want to download free Ebook, you are in the right place to download Ebook. Ebook The Fountainhead EBOOK ONLINE DOWNLOAD in English is available for free here, Click on the download LINK below to download Ebook The Fountainhead 2020 PDF Download in English by Ayn Rand (Author).

Description Book:

The revolutionary literary vision that sowed the seeds of Objectivism, Ayn Rand's groundbreaking philosophy, and brought her immediate worldwide acclaim.This modern classic is the story of intransigent young architect Howard Roark, whose integrity was as unyielding as granite...of Dominique Francon, the exquisitely beautiful woman who loved Roark passionately, but married his worst enemy...and of the fanatic denunciation unleashed by an enraged society against a great creator. As fresh today as it was then, Rand?s provocative novel presents one of the most challenging ideas in all of fiction?that man?s ego is the fountainhead of human progress...?A writer of great power. She has a subtle and ingenious mind and the capacity of writing brilliantly, beautifully, bitterly...This is the only novel of ideas written by an American woman that I can recall.??The New York Times

0 notes

Conversation

exception

Dominique Francon: Anh cũng mâu thuẫn với chính bản thân anh nữa.

Gail Wynand: Ở chỗ nào?

Dominique Francon: Tại sao anh đã không hủy diệt tôi?

Gail Wynand: Thì tạo ngoại lệ mà, Dominique. Tôi yêu em. Tôi buộc phải yêu em. Nếu em là một người đàn ông thì... cầu Chúa phù hộ cho em.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand; Quotes

Romanticism is the conceptual school of art. It deals, not with the random trivia of the day, but with the timeless, fundamental, universal problems and values of human existence. It does not record or photograph; it creates and projects. It is concerned--in the words of Aristotle--not with things as they are, but with things as they might be and ought to be.

In a play I wrote in my early thirties, Ideal, the heroine, a screen star, speaks for me when she says: "I want to see, real, living, and in the hours of my own days, that glory I create as an illusion. I want it real. I want to know that there is someone, somewhere, who wants it, too. Or else what is the use of seeing it, and working, and burning oneself for an impossible vision? A spirit, too, needs fuel. It can run dry."

I felt so profound an indignation at the state of "things as they are" that it seemed as if I would never regain the energy to move one step farther toward "things as they ought to be." Frank talked to me for hours, that night. He convinced me of why one cannot give up the world to those one despises.

The man-worshipers, in my sense of the term, are those who see man's highest potential and strive to actualize it. The man-haters are those who regard man as a helpless, depraved, contemptible creature--and struggle never to let him discover otherwise. It is important here to remember that the only direct, introspective knowledge of man anyone possesses is of himself.

"It is not the works, but the belief which is here decisive and determines the order of rank--to employ once more an old religious formula with a new and deeper meaning,--it is some fundamental certainty which a noble soul has about itself, something which is not to be sought, is not to be found, and perhaps, also, is not to be lost.--The noble soul has reverence for itself.--" (Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil.)

It is not in the nature of man--nor of any living entity--to start out by giving up, by spitting in one's own face and damning existence; that requires a process of corruption whose rapidity differs from man to man. Some give up at the first touch of pressure; some sell out; some run down by imperceptible degrees and lose their fire, never knowing when or how they lost it. Then all of these vanish in the vast swamp of their elders who tell them persistently that maturity consists of abandoning one's mind; security, of abandoning one's values; practicality, of losing self-esteem. Yet a few hold on and move on, knowing that that fire is not to be betrayed, learning how to give it shape, purpose and reality. But whatever their future, at the dawn of their lives, men seek a noble vision of man's nature and of life's potential.

He stood looking at her. She knew that he did not see her. No, she thought, it was not that exactly. He always looked straight at people and his damnable eyes never missed a thing, it was only that he made people feel as if they did not exist.

"Do you mean to tell me that you're thinking seriously of building that way, when and if you are an architect?" "Yes." "My dear fellow, who will let you?" "That's not the point. The point is, who will stop me?"

"Rules?" said Roark. "Here are my rules: what can be done with one substance must never be done with another. No two materials are alike. No two sites on earth are alike. No two buildings have the same purpose. The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be reasonable or beautiful unless it's made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. A building is alive, like a man. Its integrity is to follow its own truth, its one single theme, and to serve its own single purpose. A man doesn't borrow pieces of his body. A building doesn't borrow hunks of its soul. Its maker gives it the soul and every wall, window and stairway to express it."

Every form has its own meaning. Every man creates his meaning and form and goal. Why is it so important--what others have done? Why does it become sacred by the mere fact of not being your own? Why is anyone and everyone right--so long as it's not yourself? Why does the number of those others take the place of truth? Why is truth made a mere matter of arithmetic--and only of addition at that? Why is everything twisted out of all sense to fit everything else? There must be some reason. I don't know. I've never known it. I'd like to understand."

"If you want my advice, Peter," he said at last, "you've made a mistake already. By asking me. By asking anyone. Never ask people. Not about your work. Don't you know what you want? How can you stand it, not to know?" "You see, that's what I admire about you, Howard. You always know."

"But I mean it. How do you always manage to decide?" "How can you let others decide for you?"

'Choose the builder of your home as carefully as you choose the bride to inhabit it.'"

He demanded of all people the one thing he had never granted anybody: obedience.

Men hate passion, any great passion. Henry Cameron made a mistake: he loved his work. That was why he fought. That was why he lost.

"It's the critic's job to interpret the artist, Mr. Francon, even to the artist himself.”

"But, you see, it's not what you do that matters really. It's only you." "Me what?" "Just you here. Or you in the city. Or you somewhere in the world. I don't know. Just that."

"It's all right, dear. I understand." "If you did, you'd call me the names I deserve and make me stop it." "No, Peter. I don't want to change you. I love you, Peter." "God help you!" "I know that." "You know that? And you say it like this? Like you'd say, 'Hello, it's a beautiful evening'?" "Well, why not? Why worry about it? I love you."

"When we gaze at the magnificence of an ancient monument and ascribe its achievement to one man, we are guilty of spiritual embezzlement. We forget the army of craftsmen, unknown and unsung, who preceded him in the darkness of the ages, who toiled humbly--all heroism is humble--each contributing his small share to the common treasure of his time. A great building is not the private invention of some genius or other. It is merely a condensation of the spirit of a people."

"You want to know why I'm doing it?" Roark smiled, without resentment or interest. "Is that it? I'll tell you, if you want to know. I don't give a damn where I work next. There's no architect in town that I'd want to work for. But I have to work somewhere, so it might as well be your Francon--if I can get what I want from you. I'm selling myself, and I'll play the game that way--for the time being."

"The public taste and the public heart are the final criteria of the artist. The genius is the one who knows how to express the general. The exception is to tap the unexceptional."

Roark knew what to expect of his job. He would never see his work erected, only pieces of it, which he preferred not to see; but he would be free to design as he wished and he would have the experience of solving actual problems. It was less than he wanted and more than he could expect. He accepted it at that.

RALSTON HOLCOMBE had no visible neck, but his chin took care of that.

"Is that what you really think of them?" "Not at all. But I don't like people who try to say only what they think I think."

That's the way everybody does it. You see?" "Yes." "Then you agree?" "No."

"Listen. Roark, won't you please listen?" "I'll listen if you want me to, Mr. Snyte. But I think I should tell you now that nothing you can say will make any difference. If you don't mind that, I don't mind listening."

"It doesn't say much. Only 'Howard Roark, Architect.' But it's like those mottoes men carved over the entrance of a castle and died for. It's a challenge in the face of something so vast and so dark, that all the pain on earth--and do you know how much suffering there is on earth?--all the pain comes from that thing you are going to face. I don't know what it is, I don't know why it should be unleashed against you. I know only that it will be. And I know that if you carry these words through to the end, it will be a victory, Howard, not just for you, but for something that should win, that moves the world--and never wins acknowledgment. It will vindicate so many who have fallen before you, who have suffered as you will suffer. May God bless you--or whoever it is that is alone to see the best, the highest possible to human hearts. You're on your way into hell, Howard."

"Mike, how did you get here? Why such a come-down?" He had never known Mike to bother with small private residences. "Don't play the sap. You know how I got here. You didn't think I'd miss it, your first house, did you? And you think it's a come-down? Well, maybe it is. And maybe it's the other way around." Roark extended his hand and Mike's grimy fingers closed about it ferociously, as if the smudges he left implanted in Roark's skin said everything he wanted to say. And because he was afraid that he might say it, Mike growled: "Run along, boss, run along. Don't clog up the works like that."

"They're true, though, both sides of it, aren't they?" "Oh, sure, but couldn't you have reversed the occasions when you chose to express them?" "There wouldn't have been any point in that." "Was there any in what you've done?" "No. None at all. But it amused me." "I can't figure you out, Dominique. You've done it before. You go along so beautifully, you do brilliant work and just when you're about to make a real step forward--you spoil it by pulling something like this. Why?" "Perhaps that is precisely why." "Will you tell me--as a friend, because I like you and I'm interested in you--what are you really after?" "I should think that's obvious. I'm after nothing at all." He spread his hands open, shrugging helplessly. She smiled gaily.

"You know, Alvah, it would be terrible if I had a job I really wanted." "Well, of all things! Well, of all fool things to say! What do you mean?" "Just that. That it would be terrible to have a job I enjoyed and did not want to lose." "Why?" "Because I would have to depend on you – (…)

"It's not only that, Alvah. It's not you alone. If I found a job, a project, an idea or a person I wanted--I'd have to depend on the whole world. Everything has strings leading to everything else. We're all so tied together. We're all in a net, the net is waiting, and we're pushed into it by one single desire. You want a thing and it's precious to you. Do you know who is standing ready to tear it out of your hands? You can't know, it may be so involved and so far away, but someone is ready, and you're afraid of them all. And you cringe and you crawl and you beg and you accept them--just so they'll let you keep it. And look at whom you come to accept." "If I'm correct in gathering that you're criticizing mankind in general..." "You know, it's such a peculiar thing--our idea of mankind in general. We all have a sort of vague, glowing picture when we say that, something solemn, big and important. But actually all we know of it is the people we meet in our lifetime. Look at them. Do you know any you'd feel big and solemn about?"

As a matter of fact, one can feel some respect for people when they suffer. They have a certain dignity. But have you ever looked at them when they're enjoying themselves? That's when you see the truth.Look at those who spend the money they've slaved for--at amusement parks and side shows. Look at those who're rich and have the whole world open to them. Observe what they pick out for enjoyment. Watch them in the smarter speak-easies. That's your mankind in general. I don't want to touch it." "But hell! That's not the way to look at it. That's not the whole picture. There's some good in the worst of us. There's always a redeeming feature." "So much the worse. Is it an inspiring sight to see a man commit a heroic gesture, and then learn that he goes to vaudeville shows for relaxation? Or see a man who's painted a magnificent canvas--and learn that he spends his time sleeping with every slut he meets?" "What do you want? Perfection?" "--or nothing. So, you see, I take the nothing." "That doesn't make sense." "I take the only desire one can really permit oneself. Freedom, Alvah, freedom." "You call that freedom?" "To ask nothing. To expect nothing. To depend on nothing." "What if you found something you wanted?" "I won't find it. I won't choose to see it. It would be part of that lovely world of yours. I'd have to share it with all the rest of you--and I wouldn't. You know, I never open again any great book I've read and loved. It hurts me to think of the other eyes that have read it and of what they were. Things like that can't be shared. Not with people like that." "Dominique, it's abnormal to feel so strongly about anything." "That's the only way I can feel. Or not at all."

I had a terrible time getting it--it wasn't for sale, of course. I think I was in love with it, Alvah. I brought it home with me." "Where is it? I'd like to see something you like, for a change." "It's broken." "Broken? A museum piece? How did that happen?" "I broke it." "How?" "I threw it down the air shaft. There's a concrete floor below." "Are you totally crazy? Why?" "So that no one else would ever see it."

"I'm sorry, darling. I didn't want to shock you. I thought I could speak to you because you're the one person who's impervious to any sort of shock. I shouldn't have. It's no use, I guess."

"Pretty near the top? Is that what you think? If I can't be the very best, if I can't be the one architect of this country in my day--I don't want any damn part of it!" "Ah, but one doesn't get to that, Peter, by falling down on the job. One doesn't get to be first in anything without the strength to make some sacrifices." "But..." "Your life doesn't belong to you, Peter, if you're really aiming high.”

"You must learn how to handle people." "I can't." "Why?" "I don't know how. I was born without some one particular sense." "It's something one acquires." "I have no organ to acquire it with. I don't know whether it's something I lack, or something extra I have that stops me. Besides, I don't like people who have to be handled."

"That you didn't ask me to tell you what you are as I see you. Anybody else would have." "I'm sorry. It wasn't indifference. You're one of the few friends I want to keep. I just didn't think of asking." "I know you didn't. That's the point. You're a self-centered monster, Howard. The more monstrous because you're utterly innocent about it." "That's true." "You should show a little concern when you admit that." "Why?" "You know, there's a thing that stumps me. You're the coldest man I know. And I can't understand why--knowing that you're actually a fiend in your quiet sort of way--why I always feel, when I see you, that you're the most life-giving person I've ever met."

"Don't you see?" Roark was saying. "It's a monument you want to build, but not to yourself. Not to your own life or your own achievement. To other people. To their supremacy over you. You're not challenging that supremacy. You're immortalizing it. You haven't thrown it off--you're putting it up forever. Will you be happy if you seal yourself for the rest of your life in that borrowed shape? Or if you strike free, for once, and build a new house, your own? You don't want the Randolph place. You want what it stood for. But what it stood for is what you've fought all your life."

"but I guess that's what the public wants." "Why do you suppose they want it?" "I don't know." "Then why should you care what they want?" "You've got to consider the public." "Don't you know that most people take most things because that's what's given them, and they have no opinion whatever? Do you wish to be guided by what they expect you to think they think or by your own judgment?" "You can't force it down their throats." "You don't have to. You must only be patient. Because on your side you have reason--oh, I know, it's something no one really wants to have on his side--and against you, you have just a vague, fat, blind inertia." "Why do you think that I don't want reason on my side?" "It's not you, Mr. Janss. It's the way most people feel. They have to take a chance, everything they do is taking a chance, but they feel so much safer when they take it on something they know to be ugly, vain and stupid." "That's true, you know," said Mr. Janss.

Francon felt nothing but relief. "We knew he would, sooner or later," said Francon. "Why regret that he spared himself and all of us a prolonged agony?"

He understood that it was a confession, that answer of his, and a terrifying one. He did not know the nature of what he had confessed and he felt certain that Roark did not know it either. But the thing had been bared; they could not grasp it, but they felt its shape. And it made them sit silently, facing each other, in astonishment, in resignation. "Pull yourself together, Peter," said Roark gently, as to a comrade. "We'll never speak of that again."

Sometimes, not often, he sat up and did not move for a long time; then he smiled, the slow smile of an executioner watching a victim. He thought of his days going by, of the buildings he could have been doing, should have been doing and, perhaps, never would be doing again. He watched the pain's unsummoned appearance with a cold, detached curiosity; he said to himself: Well, here it is again. He waited to see how long it would last. It gave him a strange, hard pleasure to watch his fight against it, and he could forget that it was his own suffering; he could smile in contempt, not realizing that he smiled at his own agony. Such moments were rare. But when they came, he felt as he did in the quarry: that he had to drill through granite, that he had to drive a wedge and blast the thing within him which persisted in calling to his pity.

"I don't know what you're talking about." "If you didn't, you'd be much more astonished and much less angry, Miss Francon."

She had lost the freedom she loved. She knew that a continuous struggle against the compulsion of a single desire was compulsion also, but it was the form she preferred to accept. It was the only manner in which she could let him motivate her life. She found a dark satisfaction in pain--because that pain came from him.

He went to the quarry and he worked that day as usual. She did not come to the quarry and he did not expect her to come. But the thought of her remained. He watched it with curiosity. It was strange to be conscious of another person's existence, to feel it as a close, urgent necessity; a necessity without qualifications, neither pleasant nor painful, merely final like an ultimatum. It was important to know that she existed in the world; it was important to think of her, of how she had awakened this morning, of how she moved, with her body still his, now his forever, of what she thought.

She had not given him the one answer that would have saved her: an answer of simple revulsion--she had found joy in her revulsion, in her terror and in his strength. That was the degradation she had wanted and she hated him for it.

"Oh, not at all...." She walked away. She would not ask for his name. It was her last chance of freedom. She walked swiftly, easily, in sudden relief. She wondered why she had never noticed that she did not know his name and why she had never asked him. Perhaps because she had known everything she had to know about him from that first glance. She thought, one could not find some nameless worker in the city of New York. She was safe. If she knew his name, she would be on her way to New York now.

"If you must feel--no, not gratitude, gratitude is such an embarrassing word--but, shall we say, appreciation?"

When one makes enemies one knows that one's dangerous where it's necessary to be dangerous.

He could not identify the quality of the feeling; but he knew that part of it was a sense of shame. Once, he confessed it to Ellsworth Toohey. Toohey laughed. "That's good for you, Peter. One must never allow oneself to acquire an exaggerated sense of one's own importance. There's no necessity to burden oneself with absolutes."

"No. I don't fit, Ellsworth. Do I?" "I could, of course, ask: Into what? But supposing I don't ask it. Supposing I just say that people who don't fit have their uses also, as well as those who do? Would you like that better? Of course, the simplest thing to say is that I've always been a great admirer of yours and always will be." "That's not a compliment."

"Had I known that you were interested, I would have sent you a very special invitation." "But you didn't think I'd be interested?" "No, frankly, I..." "That was a mistake, Ellsworth. You discounted my newspaperwoman's instinct. Never miss a scoop. It's not often that one has the chance to witness the birth of a felony."

"Oh, I haven't been anywhere for a long time and I decided to start in with that. You know, when I go swimming I don't like to torture myself getting into cold water by degrees. I dive right in and it's a nasty shock, but after that the rest is not so hard to take."

"You did want me, Dominique?" "I thought I could never want anything and you suited that so well."

He did not think of Dominique often, but when he did, the thought was not a sudden recollection, it was the acknowledgment of a continuous presence that needed no acknowledgment.

"You're unpredictable enough even to be sensible at times.”

"Well, what a quaint idea! I don't know whether it's horrible or very wise indeed." "Both, Mrs. Gillespie. As all wisdom."

"You're wrong about Austen, Mr. Roark. He's very successful. In his profession and mine you're successful if it leaves you untouched." "How does one achieve that?" "In one of two ways: by not looking at people at all or by looking at everything about them."

"Which is preferable, Miss Francon?" "Whichever is hardest." "But a desire to choose the hardest might be a confession of weakness in itself." "Of course, Mr. Roark. But it's the least offensive form of confession." "If the weakness is there to be confessed at all."

There's nothing as significant as a human face. Nor as eloquent. We can never really know another person, except by our first glance at him. Because, in that glance, we know everything. Even though we're not always wise enough to unravel the knowledge. Have you ever thought about the style of a soul, Kiki?"

“....I think, Kiki, that every human soul has a style of its own, also. Its one basic theme. You'll see it reflected in every thought, every act, every wish of that person. The one absolute, the one imperative in that living creature. Years of studying a man won't show it to you. His face will. You'd have to write volumes to describe a person. Think of his face. You need nothing else." "That sounds fantastic, Ellsworth. And unfair, if true. It would leave people naked before you." "It's worse than that. It also leaves you naked before them. You betray yourself by the manner in which you react to a certain face. To a certain kind of face....The style of your soul...There's nothing important on earth, except human beings. There's nothing as important about human beings as their relations to one another...."

"And that was the famous Toohey technique. Never place your punch at the beginning of a column nor at the end. Sneak it in where it's least expected. Fill a whole column with drivel, just to get in that one important line." He bowed courteously. "Quite. That's why I like to talk to you. It's such a waste to be subtle and vicious with people who don't even know that you're being subtle and vicious.”

“All things are simple when you reduce them to fundamentals. You'd be surprised if you knew how few fundamentals there are. Only two, perhaps. To explain all of us. It's the untangling, the reducing that's difficult--that's why people don't like to bother. I don't think they'd like the results, either."

"Roark, everything I've done all my life is because it's the kind of a world that made you work in a quarry last summer." "I know that."

We are glad to listen to the sublime, but it's not necessary to be too damn reverent about the sublime.

"What shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?" Ellsworth asked: "Then in order to be truly wealthy, a man should collect souls?" The teacher was about to ask him what the hell did he mean, but controlled himself and asked what did he mean. Ellsworth would not elucidate.

He was polite, not in the manner of one seeking favor, but in the manner of one granting it.

“You're much too tense and passionate about it. A hysterical devotion to one's career does not make for happiness or success. It is wiser to select a profession about which you can be calm, sane and matter-of-fact. Yes, even if you hate it. It makes for down-to-earthness."

The young photographer glanced at Roark's face--and thought of something that had puzzled him for a long time: he had always wondered why the sensations one felt in dreams were so much more intense than anything one could experience in waking reality--why the horror was so total and the ecstasy so complete--and what was that extra quality which could never be recaptured afterward; the quality of what he felt when he walked down a path through tangled green leaves in a dream, in an air full of expectation, of causeless, utter rapture--and when he awakened he could not explain it, it had been just a path through some woods.The young photographer glanced at Roark's face--and thought of something that had puzzled him for a long time: he had always wondered why the sensations one felt in dreams were so much more intense than anything one could experience in waking reality--why the horror was so total and the ecstasy so complete--and what was that extra quality which could never be recaptured afterward; the quality of what he felt when he walked down a path through tangled green leaves in a dream, in an air full of expectation, of causeless, utter rapture--and when he awakened he could not explain it, it had been just a path through some woods.

"Of course I need you. I go insane when I see you. You can do almost anything you wish with me. Is that what you want to hear? Almost, Dominique. And the things you couldn't make me do--you could put me through hell if you demanded them and I had to refuse you, as I would. Through utter hell, Dominique. Does that please you? Why do you want to know whether you own me? It's so simple. Of course you do. All of me that can be owned. You'll never demand anything else. But you want to know whether you could make me suffer. You could. What of it?" The words did not sound like surrender, because they were not torn out of him, but admitted simply and willingly. She felt no thrill of conquest; she felt herself owned more than ever, by a man who could say these things, know of them to be true, and still remain controlled and controlling--as she wanted him to remain.

“Do you think integrity is the monopoly of the artist? And what, incidentally, do you think integrity is? The ability not to pick a watch out of your neighbor's pocket? No, it's not as easy as that. If that were all, I'd say ninety-five percent of humanity were honest, upright men. Only, as you can see, they aren't. Integrity is the ability to stand by an idea. That presupposes the ability to think. Thinking is something one doesn't borrow or pawn. And yet, if I were asked to choose a symbol for humanity as we know it, I wouldn't choose a cross nor an eagle nor a lion and unicorn. I'd choose three gilded balls."

"Don't worry. They're all against me. But I have one advantage: they don't know what they want. I do."

The point I wish to make is only that one must mistrust one's most personal impulses. What one desires is actually of so little importance! One can't expect to find happiness until one realizes this completely.

"You said something yesterday about a first law. A law demanding that man seek the best....It was funny....The unrecognized genius--that's an old story. Have you ever thought of a much worse one--the genius recognized too well?...That a great many men are poor fools who can't see the best--that's nothing. One can't get angry at that. But do you understand about the men who see it and don't want it?"

You'll say it doesn't make sense? Of course it doesn't. That's why it works. Reason can be fought with reason. How are you going to fight the unreasonable? The trouble with you, my dear, and with most people, is that you don't have sufficient respect for the senseless. The senseless is the major factor in our lives. You have no chance if it is your enemy. But if you can make it become your ally--ah, my dear!...

Don't you find it interesting to see a huge, complicated piece of machinery, such as our society, all levers and belts and interlocking gears, the kind that looks as if one would need an army to operate it--and you find that by pressing your little finger against one spot, the one vital spot, the center of all its gravity, you can make the thing crumble into a worthless heap of scrap iron? It can be done, my dear. But it takes a long time.

Hell, what's the use of accomplishing a skillful piece of work if nobody knows that you've accomplished it? Had you been your old self, you'd tell me, at this point, that that is the psychology of a murderer who's committed the perfect crime and then confesses because he can't bear the idea that nobody knows it's a perfect crime. And I'd answer that you're right. I want an audience. That's the trouble with victims--they don't even know they're victims, which is as it should be, but it does become monotonous and takes half the fun away. You're such a rare treat--a victim who can appreciate the artistry of its own execution....

He wouldn't even give you that, not even understanding, not even enough to...respect you a little just the same. I don't see what's so wrong with trying to please people. I don't see what's wrong with wanting to be friendly and liked and popular. Why is that a crime? Why should anyone sneer at you for that, sneer all the time, all the time, day and night, not giving you a moment's peace, like the Chinese water torture, you know where they drop water on your skull drop by drop?"

“When you see a man casting pearls without getting even a pork chop in return--it is not against the swine that you feel indignation. It is against the man who valued his pearls so little that he was willing to fling them into the muck and to let them become the occasion for a whole concert of grunting, transcribed by the court stenographer."

“Ask anything of men. Ask them to achieve wealth, fame, love, brutality, murder, self-sacrifice. But don't ask them to achieve self-respect. They will hate your soul. Well, they know best. They must have their reasons. They won't say, of course, that they hate you. They will say that you hate them. It's near enough, I suppose. They know the emotion involved. Such are men as they are. So what is the use of being a martyr to the impossible? What is the use of building for a world that does not exist?"

Let us destroy, but don't let us pretend that we are committing an act of virtue. Let us say that we are moles and we object to mountain peaks. Or, perhaps, that we are lemmings, the animals who cannot help swimming out to self-destruction. I realize fully that at this moment I am as futile as Howard Roark. This is my Stoddard Temple--my first and my last." She inclined her head to the judge. "That is all, Your Honor."

“Remembering that you attach such great importance to not being beaten except by your own hand, I thought you would enjoy this."

"So you people made a martyr out of me, after all. And that is the one thing I've tried all my life not to be. It's so graceless, being a martyr. It's honoring your adversaries too much. But I'll tell you this, Alvah--I'll tell it to you, because I couldn't find a less appropriate person to hear it: nothing that you do to me--or to him--will be worse than what I'll do myself. If you think I can't take the Stoddard Temple, wait till you see what I can take."

"I've been so busy...No, that's not quite true. I've had the time, but when I came home I just couldn't make myself do anything, I just fell in bed and went to sleep. Uncle Ellsworth, do people sleep a lot because they're tired or because they want to escape from something?"

“....But the poor don't hate us, as they should. They only despise us....You know, it's funny: it's the masters who despise the slaves, and the slaves who hate the masters. I don't know who is which. Maybe it doesn't fit here. Maybe it does. I don't know..."

"Don't you see how selfish you have been? You chose a noble career, not for the good you could accomplish, but for the personal happiness you expected to find in it." "But I really wanted to help people." "Because you thought you'd be good and virtuous doing it." "Why--yes. Because I thought it was right. Is it vicious to want to do right?" "Yes, if it's your chief concern. Don't you see how egotistical it is? To hell with everybody so long as I'm virtuous." "But if you have no...no self-respect, how can you be anything?" "Why must you be anything?" She spread her hands out, bewildered. "If your first concern is for what you are or think or feel or have or haven't got--you're still a common egotist." "But I can't jump out of my own body." "No. But you can jump out of your narrow soul." "You mean, I must want to be unhappy?" "No. You must stop wanting anything. You must forget how important Miss Catherine Halsey is. Because, you see, she isn't. Men are important only in relation to other men, in their usefulness, in the service they render. Unless you understand that completely, you can expect nothing but one form of misery or another. Why make such a cosmic tragedy out of the fact that you've found yourself feeling cruel toward people? So what? It's just growing pains. One can't jump from a state of animal brutality into a state of spiritual living without certain transitions. And some of them may seem evil. A beautiful woman is usually a gawky adolescent first. All growth demands destruction. You can't make an omelet without breaking eggs. You must be willing to suffer, to be cruel, to be dishonest, to be unclean--anything, my dear, anything to kill the most stubborn of roots, the ego. And only when it is dead, when you care no longer, when you have lost your identity and forgotten the name of your soul--only then will you know the kind of happiness I spoke about, and the gates of spiritual grandeur will fall open before you."

They stood silently before each other for a moment, and she thought that the most beautiful words were those which were not needed.

"Roark, before I met you, I had always been afraid of seeing someone like you, because I knew that I'd also have to see what I saw on the witness stand and I'd have to do what I did in that courtroom. I hated doing it, because it was an insult to you to defend you--and it was an insult to myself that you had to be defended....Roark, I can accept anything, except what seems to be the easiest for most people: the halfway, the almost, the just-about, the in-between. They may have their justifications. I don't know. I don't care to inquire. I know that it is the one thing not given me to understand. When I think of what you are, I can't accept any reality except a world of your kind. Or at least a world in which you have a fighting chance and a fight on your own terms. That does not exist. And I can't live a life torn between that which exists--and you. It would mean to struggle against things and men who don't deserve to be your opponents. Your fight, using their methods--and that's too horrible a desecration. It would mean doing for you what I did for Peter Keating: lie, flatter, evade, compromise, pander to every ineptitude--in order to beg of them a chance for you, beg them to let you live, to let you function, to beg them, Roark, not to laugh at them, but to tremble because they hold the power to hurt you. Am I too weak because I can't do this? I don't know which is the greater strength: to accept all this for you--or to love you so much that the rest is beyond acceptance. I don't know. I love you too much."

This is--for the time when we won't be together. I love you, Dominique. As selfishly as the fact that I exist. As selfishly as my lungs breathe air. I breathe for my own necessity, for the fuel of my body, for my survival. I've given you, not my sacrifice or my pity, but my ego and my naked need. This is the only way you can wish to be loved. This is the only way I can want you to love me. If you married me now, I would become your whole existence. But I would not want you then. You would not want yourself--and so you would not love me long. To say 'I love you' one must know first how to say the 'I.' The kind of surrender I could have from you now would give me nothing but an empty hulk. If I demanded it, I'd destroy you. That's why I won't stop you. I'll let you go to your husband. I don't know how I'll live through tonight, but I will. I want you whole, as I am, as you'll remain in the battle you've chosen. A battle is never selfless."

"You must learn not to be afraid of the world. Not to be held by it as you are now. Never to be hurt by it as you were in that courtroom. I must let you learn it. I can't help you. You must find your own way. When you have, you'll come back to me. They won't destroy me, Dominique. And they won't destroy you. You'll win, because you've chosen the hardest way of fighting for your freedom from the world. I'll wait for you. I love you. I'm saying this now for all the years we'll have to wait. I love you, Dominique." Then he kissed her and let her go.

"They say three's a crowd," laughed Keating. "But that's bosh. Two are better than one, and sometimes three are better than two, it all depends." "The only thing wrong with that old cliché," said Toohey, "is the erroneous implication that 'a crowd' is a term of opprobrium. It is quite the opposite. As you are so merrily discovering. Three, I might add, is a mystic key number. As for instance, the Holy Trinity. Or the triangle, without which we would have no movie industry. There are so many variations upon the triangle, not necessarily unhappy. Like the three of us--with me serving as understudy for the hypotenuse, quite an appropriate substitution, since I'm replacing my antipode, don't you think so, Dominique?"

Mallory had tried to object. "Shut up, Steve," Roark had said. "I'm not doing it for you. At a time like this I owe myself a few luxuries. So I'm simply buying the most valuable thing that can be bought--your time. I'm competing with a whole country--and that's quite a luxury, isn't it? They want you to do baby plaques and I don't, and I like having my way against theirs." "What do you want me to work on, Howard?" "I want you to work without asking anyone what he wants you to work on."

Roark had never seen the reconstructed Stoddard Temple. On an evening in November he went to see it. He did not know whether it was surrender to pain or victory over the fear of seeing it.

People always speak of a black death or a red death, he thought; yours, Gail Wynand, will be a gray death. Why hasn't anyone ever said that this is the ultimate horror? Not screams, pleas or convulsions. Not the indifference of a clean emptiness, disinfected by the fire of some great disaster. But this--a mean, smutty little horror, impotent even to frighten. You can't do it like that, he told himself, smiling coldly; it would be in such bad taste.

He was alone now. The curtains were open. He stood looking at the city. It was late and the great riot of lights below him was beginning to die down. He thought that he did not mind having to look at the city for many more years and he did not mind never seeing it again.

If Toohey's eyes had not been fixed insolently on Wynand's, he would have been ordered out of the office at once. But the glance told Wynand that Toohey knew to what extent he had been plagued by people recommending architects and how hard he had tried to avoid them; and that Toohey had outwitted him by obtaining this interview for a purpose Wynand had not expected. The impertinence of it amused Wynand, as Toohey had known it would.

That, Mr. Wynand, is my sincere opinion." "I quite believe you." "You do?" "Of course. But, Mr. Toohey, why should I consider your opinion?"

"Really, Mr. Toohey, I owe you an apology, if, by allowing my tastes to become so well known, I caused you to be so crude. But I had no idea that among your many other humanitarian activities you were also a pimp."

Nothing had happened to him--a happening is a positive reality, and no reality could ever make him helpless; this was some enormous negative--as if everything had been wiped out, leaving a senseless emptiness, faintly indecent because it seemed so ordinary, so unexciting, like murder wearing a homey smile. Nothing was gone--except desire; no, more than that--the root, the desire to desire. He thought that a man who loses his eyes still retains the concept of sight; but he had heard of a ghastlier blindness--if the brain centre’s controlling vision are destroyed, one loses even the memory of visual perception.

It was the lack of shock, when he thought he would kill himself, that convinced him he should. The thought seemed so simple, like an argument not worth contesting. Like a bromide. Now he stood at the glass wall, stopped by that very simplicity. One could make a bromide of one's life, he thought; but not of one's death.

It was like using a steamroller to press handkerchiefs. But he set his teeth and stuck to it.

The girl with whom he fell in love had an exquisite beauty, a beauty to be worshipped, not desired. She was fragile and silent. Her face told of the lovely mysteries within her, left unexpressed.

His decision contradicted every rule he had laid down for his career. But he did not think. It was one of the rare explosions that hit him at times, throwing him beyond caution, making of him a creature possessed by the single impulse to have his way, because the rightness of his way was so blindingly total.

The public asked for crime, scandal and sentiment. Gail Wynand provided it. He gave people what they wanted, plus a justification for indulging the tastes of which they had been ashamed.

"If you make people perform a noble duty, it bores them," said Wynand. "If you make them indulge themselves, it shames them. But combine the two--and you've got them."

"It is not my function," said Wynand, "to help people preserve a self-respect they haven't got. You give them what they profess to like in public. I give them what they really like. Honesty is the best policy, gentlemen, though not quite in the sense you were taught to believe."

Every man on earth has a soul of his own that nobody can stare at.

He moved his hand, weighing the gun. He smiled, a faint smile of derision. No, he thought, that's not for you. Not yet. You still have the sense of not wanting to die senselessly. You were stopped by that. Even that is a remnant--of something.

"Are you making fun of me, Dominique?" "Have you given me reason to?"

You wanted a mirror. People want nothing but mirrors around them. To reflect them while they're reflecting too. You know, like the senseless infinity you get from two mirrors facing each other across a narrow passage. Usually in the more vulgar kind of hotels. Reflections of reflections and echoes of echoes. No beginning and no end. No center and no purpose.

“before--you took something I had..." "No. I took something you never had. I grant you that's worse." "What?" "It's said that the worst thing one can do to a man is to kill his self-respect. But that's not true. Self-respect is something that can't be killed. The worst thing is to kill a man's pretense at it."

"Most people go to very to very great lengths in order to convince themselves of their self-respect." "Yes." "And, of course, a quest for self-respect is proof of its lack." "Yes." "Do you see the meaning of a quest for self-contempt?" "That I lack it?" "And that you'll never achieve it." "I didn't expect you to understand that either." "I won't say anything else--or I'll stop being the person before last in the world and I'll become unsuitable to your purpose." He rose. "Shall I tell you formally that I accept your offer?" She inclined her head in agreement.

"Shall I tell you the difference between you and your statue?" "No." "But I want to. It's startling to see the same elements used in two compositions with opposite themes. Everything about you in that statue is the theme of exaltation. But your own theme is suffering." "Suffering? I'm not conscious of having shown that." "You haven't. That's what I meant. No happy person can be quite so impervious to pain."

Dominique looked at the gold letters--I Do--on the delicate white bow. "What does that name mean?" she asked. "It's an answer," said Wynand, "to people long since dead. Though perhaps they are the only immortal ones. You see, the sentence I heard most often in my childhood was 'You don't run things around here.'"

"Yes, of course. Forgive me for implying any weakness in you. I know better. By the way, you haven't asked me where we're going." "That, too, would be weakness." "True. I'm glad you don't care. Because I never have any definite destination. This ship is not for going to places, but for getting away from them. When I stop at a port, it's only for the sheer pleasure of leaving it. I always think: Here's one more spot that can't hold me." "I used to travel a great deal. I always felt just like that. I've been told it's because I'm a hater of mankind." "You're not foolish enough to believe that, are you?" "I don't know."

As a matter of fact, the person who loves everybody and feels at home everywhere is the true hater of mankind. He expects nothing of men, so no form of depravity can outrage him."

"I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York's skyline. Particularly when one can't see the details. Just the shapes. The shapes and the thought that made them. The sky over New York and the will of man made visible. What other religion do we need? And then people tell me about pilgrimages to some dank pesthole in a jungle where they go to do homage to a crumbling temple, to a leering stone monster with a pot belly, created by some leprous savage. Is it beauty and genius they want to see? Do they seek a sense of the sublime? Let them come to New York, stand on the shore of the Hudson, look and kneel. When I see the city from my window--no, I don't feel how small I am--but I feel that if a war came to threaten this, I would like to throw myself into space, over the city, and protect these buildings with my body."

"It's interesting to speculate on the reasons that make men so anxious to debase themselves. As in that idea of feeling small before nature. It's not a bromide, it's practically an institution. Have you noticed how self-righteous a man sounds when he tells you about it? Look, he seems to say, I'm so glad to be a pygmy, that's how virtuous I am. Have you heard with what delight people quote some great celebrity who's proclaimed that he's not so great when he looks at Niagara Falls? It's as if they were smacking their lips in sheer glee that their best is dust before the brute force of an earthquake. As if they were sprawling on all fours, rubbing their foreheads in the mud to the majesty of a hurricane. But that's not the spirit that leashed fire, steam, electricity, that crossed oceans in sailing sloops, that built airplanes and dams...and skyscrapers. What is it they fear? What is they hate so much, those who love to crawl? And why?" "When I find the answer to that," she said, "I'll make my peace with the world."

"I often think that he's the only one of us who's achieved immortality. I don't mean in the sense of fame and I don't mean that he won't die some day. But he's living it. I think he is what the conception really means. You know how people long to be eternal. But they die with every day that passes. When you meet them, they're not what you met last. In any given hour, they kill some part of themselves. They change, they deny, they contradict--and they call it growth. At the end there's nothing left, nothing unreversed or unbetrayed; as if there had never been an entity, only a succession of adjectives fading in and out on an unformed mass. How do they expect a permanence which they have never held for a single moment? But Howard--one can imagine him existing forever."

"You understand. Nobody else does. And you like me." "Devotedly. Whenever I have the time." "Ah?"

She thought that they had not greeted each other and that it was right. This was not a reunion, but just one moment out of something that had never been interrupted. She thought how strange it would be if she ever said "Hello" to him; one did not greet oneself each morning.

"Roark, try to understand, please try to understand. I can't bear to see what they're doing to you, what they're going to do. It's too great--you and building and what you feel about it. You can't go on like that for long. It won't last. They won't let you. You're moving to some terrible kind of disaster. It can't end any other way. Give it up. Take some meaningless job--like the quarry. We'll live here. We'll have little and we'll give nothing. We'll live only for what we are and for what we know." He laughed. She heard, in the sound of it, a surprising touch of consideration for her--the attempt not to laugh; but he couldn't stop it. "Dominique." The way he pronounced the name remained with her and made it easier to hear the words that followed: "I wish I could tell you that it was a temptation, at least for a moment. But it wasn't." He added: "If I were very cruel, I'd accept it. Just to see how soon you'd beg me to go back to building." "Yes...Probably..."

"Until--when, Roark?" His hand moved over the streets. "Until you stop hating all this, stop being afraid of it, learn not to notice it."

He bowed, his manner unchanged, his calm still holding the same peculiar quality made of two things: the mature control of a man so certain of his capacity for control that it could seem casual, and a childlike simplicity of accepting events as if they were subject to no possible change.

"What's got into him?" "It's nothing that got into him, Alvah. It's something that got out at last."

She saw no apology, no regret, no resentment as he looked at her. It was a strange glance; she had noticed it before; a glance of simple worship. And it made her realize that there is a stage of worship which makes the worshiper himself an object of reverence.

"Why have you been staring at me ever since we met? Because I'm not the Gail Wynand you'd heard about. You see, I love you. And love is exception-making. If you were in love you'd want to be broken, trampled, ordered, dominated, because that's the impossible, the inconceivable for you in your relations with people. That would be the one gift, the great exception you'd want to offer the man you loved. But it wouldn't be easy for you." "If that's true, then you..." "Then I become gentle and humble--to your great astonishment--because I'm the worst scoundrel living."

"I don't want to. But I like to be honest. That has been my only private luxury. Don't change your mind about me. Go on seeing me as you saw me before we met." "Gail, that's not what you want." "It doesn't matter what I want. I don't want anything--except to own you. Without any answer from you. It has to be without answer. If you begin to look at me too closely, you'll see things you won't like at all." "What things?" "You're so beautiful, Dominique. It's such a lovely accident on God's part that there's one person who matches inside and out." "What things, Gail?" "Do you know what you're actually in love with? Integrity. The impossible. The clean, consistent, reasonable, self-faithful, the all-of-one-style, like a work of art. That's the only field where it can be found--art. But you want it in the flesh. You're in love with it. Well, you see, I've never had any integrity."

"All right, Gail. Let's go in. It's too cold for you here without an overcoat." He chuckled softly--it was the kind of concern she had never shown for him before. He took her hand and kissed her palm, holding it against his face. # For many weeks, when left alone together, they spoke little and never about each other. But it was not a silence of resentment; it was the silence of an understanding too delicate to limit by words. They would be in a room together in the evening, saying nothing, content to feel each other's presence. They would look at each other suddenly--and both would smile, the smile like hands clasped.

"Gail," she said gently, "some day I'll have to ask your forgiveness for having married you." He shook his head slowly, smiling. She said: "I wanted you to be my chain to the world. You've become my defense, instead. And that makes my marriage dishonest." "No. I told you I would accept any reason you chose." "But you've changed everything for me. Or was it I that changed it? I don't know. We've done something strange to each other. I've given you what I wanted to lose. That special sense of living I thought this marriage would destroy for me. The sense of life as exaltation. And you--you've done all the things I would have done. Do you know how much alike we are?" "I knew that from the first." "But it should have been impossible. Gail, I want to remain with you now--for another reason. To wait for an answer. I think when I learn to understand what you are, I'll understand myself. There is an answer. There is a name for the thing we have in common. I don't know it. I know it's very important." "Probably. I suppose I should want to understand it. But I don't. I can't care about anything now. I can't even be afraid." She looked up at him and said very calmly: "I am afraid, Gail." "Of what, dearest?" "Of what I'm doing to you." "Why?" "I don't love you, Gail." "I can't care even about that." She dropped her head and he looked down at the hair that was like a pale helmet of polished metal. "Dominique." She raised her face to him obediently. "I love you, Dominique. I love you so much that nothing can matter to me--not even you. Can you understand that? Only my love--not your answer. Not even your indifference. I've never taken much from the world. I haven't wanted much. I've never really wanted anything. Not in the total, undivided way, not with the kind of desire that becomes an ultimatum, 'yes' or 'no,' and one can't accept the 'no' without ceasing to exist. That's what you are to me. But when one reaches that stage, it's not the object that matters, it's the desire. Not you, but I. The ability to desire like that. Nothing less is worth feeling or honoring. And I've never felt that before. Dominique, I've never known how to say 'mine' about anything. Not in the sense I say it about you. Mine. Did you call it a sense of life as exaltation? You said that. You understand. I can't be afraid. I love you, Dominique--I love you--you're letting me say it now--I love you."

Men have not found the words for it nor the deed nor the thought, but they have found the music. Let me see that in one single act of man on earth. Let me see it made real. Let me see the answer to the promise of that music. Not servants nor those served; not altars and immolations; but the final, the fulfilled, innocent of pain. Don't help me or serve me, but let me see it once, because I need it. Don't work for my happiness, my brothers--show me yours--show me that it is possible--show me your achievement--and the knowledge will give me courage for mine.

Music, he thought, the promise of the music he had invoked, the sense of it made real--there it was before his eyes--he did not see it--he heard it in chords--he thought that there was a common language of thought, sight and sound--was it mathematics?--the discipline of reason--music was mathematics--and architecture was music in stone--he knew he was dizzy because this place below him could not be real.

And then he saw Mr. Bradley come to visit the site, to smile blandly and depart again. Then Mallory felt anger without reason--and fear. "Howard," Mallory said one night, when they sat together at a fire of dry branches on the hillside over the camp, "it's the Stoddard Temple again." "Yes," said Roark. "I think so. But I can't figure out in just what way or what they're after." He rolled over on his stomach and looked down at the panes of glass scattered through the darkness below; they caught reflections from somewhere and looked like phosphorescent, self-generated springs of light rising out of the ground. He said: "It doesn't matter, Steve, does it? Not what they do about it nor who comes to live here. Only that we've made it. Would you have missed this, no matter what price they make you pay for it afterward?" "No," said Mallory.

But the root of evil--my drooling beast--it's there. Howard, in that story. In that--and in the souls of the smug bastards who'll read it and say: 'Oh well, genius must always struggle, it's good for 'em'--and then go and look for some village idiot to help, to teach him how to weave baskets. That's the drooling beast in action.

It takes two to make a very great career: the man who is great, and the man--almost rarer--who is great enough to see greatness and say so."

"Most people build as they live--as a matter of routine and senseless accident. But a few understand that building is a great symbol. We live in our minds, and existence is the attempt to bring that life into physical reality, to state it in gesture and form. For the man who understands this, a house he owns is a statement of his life. If he doesn't build, when he has the means, it's because his life has not been what he wanted."

"I never meet the men whose work I love. The work means too much to me. I don't want the men to spoil it. They usually do. They're an anticlimax to their own talent. You're not. I don't mind talking to you. I told you this only because I want you to know that I respect very little in life, but I respect the things in my gallery, and your buildings, and man's capacity to produce work like that. Maybe it's the only religion I've ever had." He shrugged.

"I want it to be a palace--only I don't think palaces are very luxurious. They're so big, so promiscuously public. A small house is the true luxury. A residence for two people only--for my wife and me. It won't be necessary to allow for a family, we don't intend to have children. Nor for visitors, we don't intend to entertain. One guest room--in case we should need it--but not more than that. Living room, dining room, library, two studies, one bedroom. Servants' quarters, garage. That's the general idea.

"I can't pretend an anger I don't feel," said Roark. "It's not pity. It's much more cruel than anything I could do. Only I'm not doing it in order to be cruel. If I slapped your face, you'd forgive me for the Stoddard Temple." "Is it you who should seek forgiveness?" "No. You wish I did. You know that there's an act of forgiveness involved. You're not clear about the actors. You wish I would forgive you--or demand payment, which is the same thing--and you believe that that would close the record. But, you see, I have nothing to do with it. I'm not one of the actors. It doesn't matter what I do or feel about it now. You're not thinking of me. I can't help you. I'm not the person you're afraid of just now." "Who is?" "Yourself." "Who gave you the right to say all this?" "You did." "Well, go on." "Do you wish the rest?" "Go on." "I think it hurts you to know that you've made me suffer. You wish you hadn't. And yet there's something that frightens you more. The knowledge that I haven't suffered at all." "Go on." "The knowledge that I'm neither kind nor generous now, but simply indifferent. It frightens you, because you know that things like the Stoddard Temple always require payment--and you see that I'm not paying for it. You were astonished that I accepted this commission. Do you think my acceptance required courage? You needed far greater courage to hire me. You see, this is what I think of the Stoddard Temple. I'm through with it. You're not." Wynand let his fingers fall open, palms out. His shoulders sagged a little, relaxing. He said very simply: "All right. It's true. All of it."

Did you want to scream, when you were a child, seeing nothing but fat ineptitude around you, knowing how many things could be done and done so well, but having no power to do them? Having no power to blast the empty skulls around you? Having to take orders--and that's bad enough--but to take orders from your inferiors! Have you felt that?" "Yes." "Did you drive the anger back inside of you, and store it, and decide to let yourself be torn to pieces if necessary, but reach the day when you'd rule those people and all people and everything around you?" "No." "You didn't? You let yourself forget?" "No. I hate incompetence. I think it's probably the only thing I do hate. But it didn't make me want to rule people. Nor to teach them anything. It made me want to do my own work in my own way and let myself be torn to pieces if necessary."

"What you feel in the presence of a thing you admire is just one word--'Yes.' The affirmation, the acceptance, the sign of admittance. And that 'Yes' is more than an answer to one thing, it's a kind of 'Amen' to life, to the earth that holds this thing, to the thought that created it, to yourself for being able to see it. But the ability to say 'Yes' or 'No' is the essence of all ownership. It's your ownership of your own ego. Your soul, if you wish. Your soul has a single basic function--the act of valuing. 'Yes' or 'No,' 'I wish' or 'I do not wish.' You can't say 'Yes' without saying 'I.' There's no affirmation without the one who affirms. In this sense, everything to which you grant your love is yours." "In this sense, you share things with others?" "No. It's not sharing. When I listen to a symphony I love, I don't get from it what the composer got. His 'Yes' was different from mine. He could have no concern for mine and no exact conception of it. That answer is too personal to each man But in giving himself what he wanted, he gave me a great experience. I'm alone when I design a house, Gail, and you can never know the way in which I own it. But if you said you own 'Amen' to it--it's also yours. And I'm glad it's yours."

"You told them you don't co-operate or collaborate." "But it wasn't a gesture, Gail. It was plain common sense. One can't collaborate on one's own job. I can co-operate, if that's what they call it, with the workers who erect my buildings. But I can't help them to lay bricks and they can't help me to design the house."

He leaned against the filing cabinet, letting his feet slide forward, his arms crossed, and he spoke softly: "Howard I had a kitten once. The damn thing attached itself to me--a flea-bitten little beast from the gutter, just fur, mud and bones--followed me home, I fed it and kicked it out, but the next day there it was again, and finally I kept it. I was seventeen then, working for the Gazette, just learning to work in the special way I had to learn for life. I could take it all right, but not all of it. There were times when it was pretty bad. Evenings, usually. Once I wanted to kill myself. Not anger--anger made me work harder. Not fear. But disgust, Howard. The kind of disgust that made it seem as if the whole world were under water and the water stood still, water that had backed up out of the sewers and ate into everything, even the sky, even my brain. And then I looked at that kitten. And I thought that it didn't know the things I loathed, it could never know. It was clean--clean in the absolute sense, because it had no capacity to conceive of the world's ugliness. I can't tell you what relief there was in trying to imagine the state of consciousness inside that little brain, trying to share it, a living consciousness, but clean and free. I would lie down on the floor and put my face on that cat's belly, and hear the beast purring. And then I would feel better....There, Howard. I've called your office a rotting wharf and yourself an alley cat. That's my way of paying homage." Roark smiled. Wynand saw that the smile was grateful.

But it hurts me, he thought. It hurts me every time I think of him. It makes everything easier--the people, the editorials, the contracts--but easier because it hurts so much. Pain is a stimulant also. I think I hate that name. I will go on repeating it. It is a pain I wish to bear.

Structure, thought Wynand, is a solved problem of tension, of balance, of security in counterthrusts.

"I was thinking of people who say that happiness is impossible on earth. Look how hard they all try to find some joy in life. Look how they struggle for it. Why should any living creature exist in pain? By what conceivable right can anyone demand that a human being exist for anything but his own joy? Every one of them wants it. Every part of him wants it. But they never find it. I wonder why. They whine and say they don't understand the meaning of life. There's a particular kind of people that I despise. Those who seek some sort of a higher purpose or 'universal goal,' who don't know what to live for, who moan that they must 'find themselves.' You hear it all around us. That seems to be the official bromide of our century. Every book you open. Every drooling self-confession. It seems to be the noble thing to confess. I'd think it would be the most shameful one." "Look, Gail." Roark got up, reached out, tore a thick branch off a tree, held it in both hands, one fist closed at each end; then, his wrists and knuckles tensed against the resistance, he bent the branch slowly into an arc. "Now I can make what I want of it: a bow, a spear, a cane, a railing. That's the meaning of life." "Your strength?" "Your work." He tossed the branch aside. "The material the earth offers you and what you make of it...What are you thinking of, Gail?" "The photograph on the wall of my office."

If you want something to grow, you don't nurture each seed separately. You just spread a certain fertilizer. Nature will do the rest.

"What do you mean?" "Nothing that you could possibly grasp. And I must not overtax your strength. You don't look as if you had much to spare."

You can devote your life to pulling out each single weed as it comes up--and then ten lifetimes won't be enough for the job. Or you can prepare your soil in such a manner--by spreading a certain chemical, let us say--that it will be impossible for weeds to grow. This last is faster.

"Ellsworth, I don't know what you're talking about." "But of course you don't. That's my advantage I say these things publicly every single day--and nobody knows what I'm talking about."

"You want to do it?" "I might. If you offer me enough." "Howard--anything you ask. Anything. I'd sell my soul..." "That's the sort of thing I want you to understand. To sell your soul is the easiest thing in the world. That's what everybody does every hour of his life. If I asked you to keep your soul--would you understand why that's much harder?" "Yes...Yes, I think so."

I worked because I can't look at any material without thinking: What could be done with it? And the moment I think that, I've got to do it. To find the answer, to break the thing. I've worked on it for years. I loved it. I worked because it was a problem I wanted to solve.

You see, I'm never concerned with my clients, only with their architectural requirements. I consider these as part of my building's theme and problem, as my building's material--just as I consider bricks and steel. Bricks and steel are not my motive. Neither are the clients. Both are only the means of my work. Peter, before you can do things for people, you must be the kind of man who can get things done. But to get things done, you must love the doing, not the secondary consequences. The work, not the people. Your own action, not any possible object of your charity. I'll be glad if people who need it find a better manner of living in a house I designed. But that's not the motive of my work. Nor my reason. Nor my reward."

Well, I've told you all the things in which I don't believe, so that you'll understand what I want and what right I have to want it. I don't believe in government housing. I don't want to hear anything about its noble purposes. I don't think they're noble. But that, too, doesn't matter. That's not my first concern. Not who lives in the house nor who orders it built. Only the house itself. If it has to be built, it might as well be built right."

The only thing that matters, my goal, my reward, my beginning, my end is the work itself. My work done my way. Peter, there's nothing in the world that you can offer me, except this. Offer me this and you can have anything I've got to give. My work done my way. A private, personal, selfish, egotistical motivation. That's the only way I function. That's all I am."

"What are you talking about?" "Nothing. Don't pay any attention. I'm half asleep." She thought: This is the tribute to Gail, the confidence of surrender--he relaxes like a cat--and cats don't relax except with people they like.

You and he as inseparable friends upsets every rational concept I've ever held. After all, there are distinct classes of humanity--no, I'm not talking Toohey's language--but there are certain boundary lines among men which cannot be crossed." "Yes, there are. But nobody has ever given the proper statement of where they must be drawn."

"You see how stupid those things sound. It's natural for you to be a little contrite--a normal reflex--but we must look at it objectively, we're grownup, rational people, nothing is too serious, we can't really help what we do, we're conditioned that way, we just charge it off to experience and go on from there."

"Katie...for six years...I thought of how I'd ask your forgiveness some day. And now I have the chance, but I won't ask it. It seems...it seems beside the point. I know it's horrible to say that, but that's how it seems to me. It was the worst thing I ever did in my life--but not because I hurt you. I did hurt you, Katie, and maybe more than you know yourself. But that's not my worst guilt....Katie, I wanted to marry you. It was the only thing I ever really wanted. And that's the sin that can't be forgiven--that I hadn't done what I wanted. It feels so dirty and pointless and monstrous, as one feels about insanity, because there's no sense to it, no dignity, nothing but pain--and wasted pain....Katie, why do they always teach us that it's easy and evil to do what we want and that we need discipline to restrain ourselves? It's the hardest thing in the world--to do what we want. And it takes the greatest kind of courage. I mean, what we really want. As I wanted to marry you. Not as I want to sleep with some woman or get drunk or get my name in the papers. Those things--they're not even desires--they're things people do to escape from desires--because it's such a big responsibility, really to want something."

Katie?...People always regret that the past is so final, that nothing can change it--but I'm glad it's so. We can't spoil it. We can think of the past, can't we? Why shouldn't we? I mean, as you said, like grownup people, not fooling ourselves, not trying to hope, but only to look back at it....

"I'm not running away from my work, if that's what surprises you. I know when to stop--and I can't stop, unless it's completely. I know I've overdone it. I've been wasting too much paper lately and doing awful stuff." "Do you ever do awful stuff?" "Probably more of it than any other architect and with less excuse. The only distinction I can claim is that my botches end up in my own wastebasket."

"You made a mistake on the Stoddard Temple, Howard. That statue should have been, not of Dominique, but of you." "No. I'm too egotistical for that." "Egotistical? An egotist would have loved it. You use words in the strangest way." "In the exact way. I don't wish to be the symbol of anything. I'm only myself."

"I erased my ego out of existence in a way never achieved by any saint in a cloister. Yet people call me corrupt. Why? The saint in a cloister sacrifices only material things. It's a small price to pay for the glory of his soul. He hoards his soul and gives up the world. But I--I took automobiles, silk pyjamas, a penthouse, and gave the world my soul in exchange. Who's sacrificed more--if sacrifice is the test of virtue? Who's the actual saint?"

“What else can one do if one must serve the people? If one must live for others? Either pander to everybody's wishes and be called corrupt; or impose on everybody by force your own idea of everybody's good. Can you think of any other way?" "No."

“What else can one do if one must serve the people? If one must live for others? Either pander to everybody's wishes and be called corrupt; or impose on everybody by force your own idea of everybody's good. Can you think of any other way?" "No." "What's left then? Where does decency start? What begins where altruism ends?”